The impact of HPAI trade restrictions on U.S. poultry exports in 2022–23

Editor in charge: Gopinath Munisamy

Abstract

In early 2022, APHIS confirmed a case of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), signaling the beginning of an extensive HPAI outbreak. Since the start of the outbreak in 2022, more than 105 million birds across commercial and backyard operations in 48 states have been affected. Many countries, including top importers of U.S. poultry meat and products, have imposed trade restrictions on U.S. poultry exports in response to the outbreak. We examine the impacts of county- and state-level restrictions and HPAI cases on U.S. poultry exports in 2022 and 2023 using a fixed-effects Poisson model. We find that state-level restrictions have a negative and statistically significant effect on export value, associated with a 60% decline in real export value, compared to when no state restrictions are in place. Conversely, county-level restrictions are associated with a 16% decline, suggesting that geographic granularity is an important determinant of the impact of a ban and USDA efforts to negotiate for more localized restrictions ensure the continuation of U.S. poultry exports under an animal health emergency.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) can rapidly spread among poultry operations, decimating flocks with mortality rates above 75%. Losses to international markets, business disruptions, and elevated biosecurity spending compound these direct losses (MacLachlan et al., 2022; Ramos et al., 2017). On February 9, 2022, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) detected a case of HPAI in a commercial turkey flock in Indiana, representing the advent of an extensive HPAI outbreak. Since the start of the outbreak, more than 105 million birds across commercial and backyard operations in 48 states have been affected by the disease (USDA-APHIS, 2023). The outbreak has continued through 2025, making this outbreak the largest poultry health episode in U.S. history, surpassing the 2014–15 outbreak.

During the 2014–15 outbreak, many countries restricted U.S. poultry and egg exports with national- and state-level bans, which followed the World Organization for Animal Health's (WOAH) guidelines. Trade restrictions disproportionately impacted producers of chicken meat (broiler), which experienced a lower rate of direct losses (MacLachlan et al., 2022). Similarly, the start of the 2022 HPAI outbreak triggered domestic disease control and trade restrictions from trade partners. Contrasting with the 2014–15 outbreak, negotiations between APHIS and U.S. trade partners resulted in more localized and county-level restrictions than prior outbreaks (Swayne et al., 2017). This more granular regionalization—often described as compartmentalization—provided a clear policy response to HPAI as the disease spread. In addition, some countries exempt heat-treated poultry (e.g., cooked poultry and egg products) from these restrictions.

In this study, we describe HPAI-related trade restrictions adopted during 2022–23 and estimate the average effect of trade restrictions on U.S. poultry exports. More specifically, using a panel of monthly, state-level exports to foreign partners, we estimate how different regionalization of trade restrictions (county vs. state restrictions) heterogeneously affected real U.S. poultry export values from a state to a trading partner using a fixed-effects (FE) Poisson model. This work explores the benefits of regionalizing outbreak-related trade restrictions, following Seitzinger and Paarlberg's (2016) recommendations of using state-level trade flows to evaluate changes in the geographical scope of restrictions. Furthermore, localized restrictions have been adopted at a much higher rate during the most recent outbreak. Over 60% of trading partners that imposed a ban adopted county or zone-level restrictions in 2022–23 compared with only 20% of partners during the 2014–15 HPAI outbreak. This growing adoption suggests that state-level exports would facilitate the analysis of the effects of localized trade restrictions.

We contribute to three key findings to the literature. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this study provides the first evaluation of the impact of HPAI and subsequent localized trade restrictions on U.S. poultry in 2022 and 2023. Other studies have analyzed the effects of trade restrictions during prior outbreaks using simulation (Johnson et al., 2014) and gravity models (Thompson, 2018). In this article, we exploit state-level variation in the restrictions and combine these data with state-to-country exports to create a monthly panel. Furthermore, we do not use a gravity model as we lack information on state-to-state trade flows and foreign exports to the United States (Yotov, 2022).

Second, we have compiled export restrictions on U.S. poultry from the USDA-Food Safety and Inspection Service's (FSIS) Import & Export Library from 2022 to 2023. This country-specific data details the type of restriction, state and county affected (if applicable), the restriction coverage period (including restart dates for restrictions), and whether products can receive an exemption following heat treatment. Researchers will directly benefit from this readily usable data when studying the trade environment surrounding the most recent HPAI outbreak.

Lastly, the importance of poultry exports to the agricultural sector motivates our empirical study of the outbreak and subsequent trade-policy responses on the export market. Past research found severe losses stemming from animal disease outbreaks. MacLachlan et al. (2022) find that chicken meat exports decreased by approximately 145,000 tons, and APHIS estimated losses of $879 million over the 10-month, 2014–15 outbreak window. Similarly, Ramos et al. (2017) find that while egg and turkey production returned to more typical levels in 2016, poultry exports did not return to pre-outbreak levels. Persistent restrictions on U.S. poultry from important trade partners extended the economic impact of the outbreak beyond infections. These trade distortions typically reduce the well-being of producers as their pool of potential consumers shrinks.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 provides background on the HPAI situation in 2022–23 and subsequent trade restrictions. Section 2 describes the data used to assess the impacts of the restrictions on poultry exports. Section 3 explains our modeling approach, followed by the results and discussion. Section 6 concludes with suggestions for future research.

OVERVIEW OF HPAI OUTBREAKS IN THE UNITED STATES

Avian influenza includes the respiratory diseases caused by influenza (often called “flu”) Type A viruses originating among avian species. While these viruses often adapt to spread among avian hosts, they may also be transmitted to other hosts, including humans and other mammals. In 2024, cases of HPAI were confirmed among dairy cattle and a livestock handler (Ly, 2024). WOAH and APHIS categorize avian influenzas as either “low pathogenic” or “highly pathogenic” based on their genetic composition and the severity of the illness (USDA-APHIS, 2016). Those viruses causing mortality in more than 75% of poultry birds are classified as highly pathogenic, and the rest are categorized as low pathogenic. Most viruses cause no visible clinical signs of disease in poultry and fall within low pathogenicity (Spickler et al., 2008). By contrast, symptoms of HPAI include decreased food and water consumption, coughing, sneezing, decreased egg production (or soft, deformed eggs), and sudden death (Swayne & Suarez, 2000).

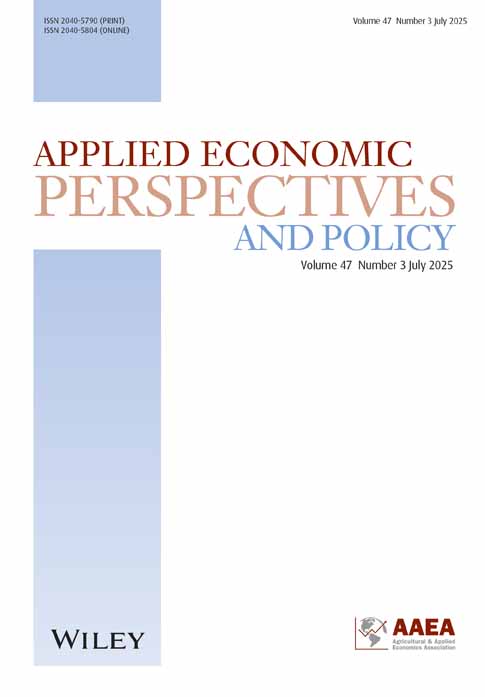

The outbreak that began in 2022 among domestic poultry began in Dubois County, Indiana with a commercial turkey operation where 29,000 birds were affected (Figure 1a). In 2022 and 2023, approximately 78 million birds were affected across 500 commercial flocks, making this HPAI outbreak the largest in U.S. history. In comparison, 50.5 million birds were affected in the 2014–15 outbreak (Table 1).

Source: USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) data on HPAI confirmations in 2022–23

.| HPAI outbreaks | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 | 2022–23 | |

| Layers affected (millions) | 36 | 58.8 |

| Turkeys affected (millions) | 7.4 | 13.2 |

| Broilers affected | <0.01 of inventory | 5.3 million |

| Total birds (millions) | 50.5 | 77.3 |

| Commercial flocks | 211 | 500 |

| Backyard flocks | 21 | 655 |

| Duration of the outbreak (months) | 7 | 26 (ongoing) |

| States affected | 15 | 47 |

- Note: The most recent HPAI outbreak is ongoing; these counts are for the 2022 and 2023 years and do not include 2024 numbers. These counts only include birds in commercial operations.

- Source: USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Final Report for the 2014–15 outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in the United States.

Table-egg-laying chickens and turkeys grown for meat experienced the greatest production losses, with infections reaching 58.8 million and 13.2 million, respectively (Figure 1b). As in the 2014–15 outbreak, HPAI marginally affected broiler production, with 3.5 million birds affected (5% of total infections). Most HPAI cases in commercial operations occurred between March and May 2022, with infections slowing down during the summer months and increasing again between September and December 2022 (Figure 1b). In 2023, infections reached approximately 21.8 million birds in commercial operations, a sharp decline from infections in 2022.

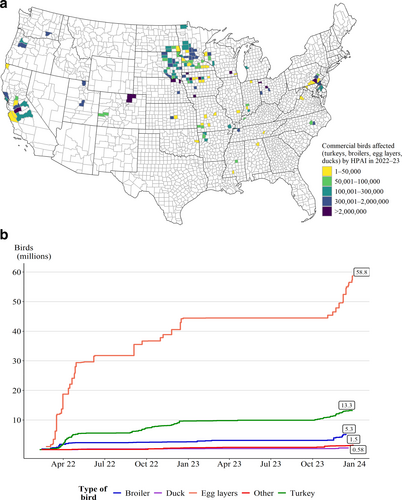

Regarding the geographical spread of the outbreak, APHIS confirmed detections of HPAI among birds across 47 states—every state but Hawaii, West Virginia, and Louisiana. Commercial turkey operations in Minnesota and South Dakota reported the greatest numbers of affected birds, followed by Iowa and Utah (Figure 2). In Iowa, Ohio, Colorado, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania, table-egg layer operations lost the most birds. The distribution of cases across states during 2022 and 2023 differs markedly from the 2014 to 15 outbreak. In 2014–15, the outbreak reached 211 commercial operations in nine states and 21 backyard operations in 11 states. Iowa and Minnesota represented the largest shares of affected commercial birds (Thompson & Pendell, 2016; USDA-APHIS, 2016).

Source: USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) data on HPAI confirmations in 2022–23

.DATA

To estimate the trade impacts of HPAI, we rely on data from several USDA agencies, including FSIS, the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), and APHIS. Each following subsection describes a series within our monthly panel spanning 2022 and 2023.

Export restrictions from the food, safety, and inspection service's import and export library

We compile daily data on export restrictions from the FSIS's Import and Export Library from February 2022 to December 2023 (USDA-FSIS, 2022b). These restrictions, imposed by U.S. trading partners, limit the entry of U.S. poultry products that either originated or were slaughtered in a restricted area. Restrictions can be nationwide, but more often tend to be at the state-, county-, or zone-level (e.g., 10-km radius). We omit national-level restrictions because most countries imposing national bans imposed them before the most recent outbreak. In this paper, we exclusively focus on restrictions imposed in response to the most recent HPAI outbreak.

Trade restrictions vary over time and are often determined by the trading partner's policies regarding HPAI cases. Trading partners can change these policies or alter their implementation as new information becomes available. For example, Mexico initially banned poultry products from an entire state at the first confirmed case of HPAI in commercial operation. Following a statewide ban, APHIS submits a cover letter and a mandatory questionnaire to Mexico requesting a change from state- to county-level restrictions. If surveillance efforts satisfy Mexico's requirements and cases are limited to a few counties, then restrictions change from state level to county level. By contrast, the official policy of the Mexican government in 2015 was to implement state-level bans at first confirmation and then maintain this ban during the duration of the outbreak. Other countries, such as Japan, initially impose county-level restrictions and then expand to state-level restrictions if cases spread throughout the state.

Over half of U.S. trading partners have restrictions on importing poultry products, most of which are county-level (Table 2). Only 15 countries imposed state-level bans on poultry in 2022 and 2023, with five of those countries using both state- and county-level restrictions. Lastly, countries with nationwide bans on U.S. poultry include Israel, Australia, Thailand, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Brazil, Russia, Sudan, and Malaysia. The majority of these countries, such as Nigeria, Thailand, Russia, Brazil, and Argentina, had bans in place prior to the outbreak. Table 2 summarizes restrictions among countries that imported U.S. poultry products in 2022 and 2023.

| Variable | Mean | St. dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Exports of poultry products in 2022–23 with county-level restrictions* (%) | 72.2 | 44.8 |

| Exports of poultry products in 2022–23 with state-level restrictions* (%) | 21.8 | 41.3 |

| Exports of poultry products in 2022–23 with national-level restrictions* (%) | 6.0 | 23.7 |

| Exports of poultry products in 2022–23 with a heat exemption (%) | 51.2 | 49.9 |

| Average duration of a restriction (days) | 170.0 | 118.4 |

| Share of 2022 exports under restriction | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| Share of 2023 exports under restriction | 0.16 | 0.35 |

| Number of trading partners in 2022–23 without a trade restriction | 65 | - |

| Number of trading partners in 2022–23 with a county-level restriction | 55 | - |

| Number of trading partners in 2022–23 with a state-level restriction | 15 | - |

| Number of trading partners in 2022–23 with a national ban | 10 | - |

- Note: *These percentages are conditional on having a restriction in place and export value being greater than zero.

Exclusively examining the top destinations for U.S. poultry, several countries that imposed state-level restrictions during the 2014–15 outbreak opted for county-level restrictions in response to the most recent outbreak. China had a national ban on U.S. poultry products during the 2014–15 outbreak and, in 2022, imposed state-level bans following HPAI cases (Table 3). Overall, the share of exports to the top importers of U.S. poultry products remained largely consistent, with over half of importers seeing an increase in export share in 2022 and 2023, relative to 2021.

| Partner | Restriction type (2014–15) | Restriction type (2022–23) | Heat-treated exemption (2022–23) | Percentage of total of U.S. poultry meat and product export value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

| Mexico | State | County/State | Yes | 25.4 | 21.0 | 23.0 |

| China | National | State | Yes | 16.8 | 18.3 | 13.4 |

| Cuba | State | County/State | No | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| Taiwan | State | State | No | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6.5 |

| Canada | County | County | Yes | 7.5 | 9.5 | 9.1 |

| Philippines | State | State | Yes | 2.8 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Angola | None | None | No | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Guatemala | County/State | County | Yes | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Vietnam | State | County | No | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Hong Kong | County | County | Yes | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.9 |

- Notes: Poultry meat and products include the following Harmonized System (HS) Codes: 020710–020714, 020721–020727, 020731–020736, 020739, 020741–020745, 020750–020755, 020760, 160231, 160232, 160239. Mexico and Cuba have both state- and county-level restrictions.

FAS global agricultural trade system poultry export value

To measure the effect of trade restrictions and HPAI on poultry meat exports, we use monthly, state-country export data from USDA-FAS, Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS). The data span from January 2018 to December 2023, including export data from 2018 to 2021 to better control for trade flows prior to the outbreak (USDA-FAS, 2024). Using state-level exports to specific trading partners, we can take advantage of the geographic granularity of trade restrictions as well as the time variation. However, the GATS database reports state-level exports using the origin of movement (OM) method (Morgan et al., 2022). This method attempts to measure state exports on the basis of transportation origin, defined as “the location from which exports begin their journey to the port of exit” (ITA, 2005). This simplification can lead to understating exports of land-locked agricultural states, while overstating exports from states with ports. While this is a limitation of the database, we find that there is a strong overlap between the top chicken and turkey meat exporting states (as reported in GATS) and top producers of broilers and turkeys (USDA-NASS, 2024). This overlap suggests that the state of origin of movement and the state of production for these consumer goods tend to be the same, as many of the top chicken producing states and packing plants are located in the south, in states with a port.

In this data set, we aggregate the export values of chicken, turkey, duck, and geese into a single value.1 While aggregation limits our ability to analyze the effects of restrictions on different poultry products, most poultry exports (between 67% and 70%) during the study period were chicken cuts (HS-6, 020714). The lack of variation in product type suggests minimal gains from disaggregation. We deflate export value using the Producer Price Index (PPI) commodity data for processed foods and feeds-processed poultry, with December 2023 as the base (BLS, 2024).2

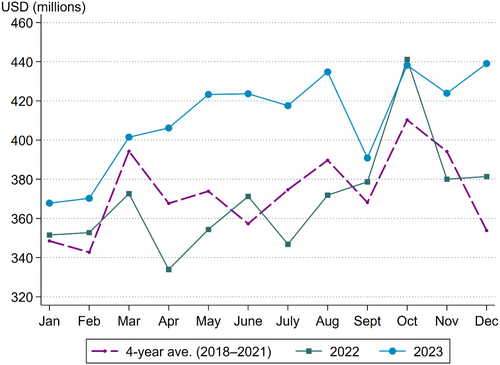

Compared with the 4-year average from 2018 to 2021, real export values for poultry meat and products in 2022 started to decrease shortly after the first detected case of HPAI. Subsequently, poultry exports started to increase in the months of September, October, and December 2022, as HPAI cases started to decline (Figure 3). Conversely, real export values in 2023 were above their 4-year average.

Source: USDA-Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS) data

.Locations of slaughter plants

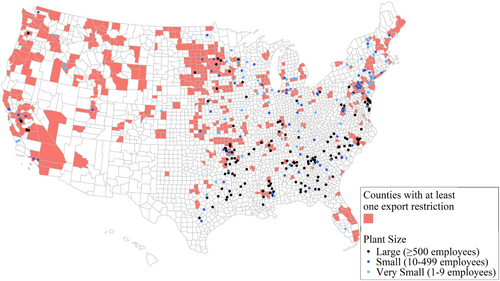

We combine export restriction data with FSIS data on the location of poultry slaughter plants to measure the percentage of slaughter plants under restrictions in each state each month (USDA-FSIS, 2022a). In the study, this percentage varies by trading partner since restrictions ended and started at different times depending on each country's policies regarding HPAI. By incorporating a measure of the percentage of processing plants affected by restrictions, we can better estimate the effects of restrictions on poultry producers. The overlap of county restrictions and large poultry slaughter plants suggests that the geographical granularity of the restriction could help limit the effect of restrictions on exports (Figure 4). For example, only 34% of slaughter plants in 2022 and 2023 were in counties with a county-level export restriction. However, some trading partners imposed state-level restrictions, meaning poultry derived or slaughtered from any county in the restricted state would be banned. We use this variable in lieu of the percent of restricted poultry operations, derived from the number of poultry operations by county reported in 2017 Census of Agriculture because the data are suppressed for some counties due to disclosure concerns. In addition, these variables are highly correlated.3

Source: USDA-Food Safety and Inspection Service's (FSIS) Meat, Poultry and Egg Product Inspection (MPI) Directory and USDA-FSIS Import and Export Library

.MODEL SPECIFICATION

We estimate both equations using a FE Poisson to account for the time-invariant characteristics and the structure of the dependent variable with only nonnegative responses, including a large portion of zeroes. Despite the strong underlying assumption of equidispersion of the conditional mean and variance, Wooldridge (1999) finds the FE Poisson produces consistent estimators of the mean effects under any kind of mean/variance relationship, as long as the conditional mean assumption is met. An alternative estimation strategy would be the FE-negative binomial; however, Guimaraes (2008) finds that a FE-negative binomial only controls for time-invariant characteristics if the individual fixed effects and the individual parameter of overdispersion are related in a very specific way—imposing a strong assumption to control for heterogeneity. Lastly, in this study, real export value includes zeros for state exports to countries that were positive in a prior year. The Poisson estimator can accommodate these observations as well as those with large, positive outcomes (Correia et al., 2020; Wooldridge, 1999). We cluster standard errors at the state level.

RESULTS

Table 4 displays the coefficient estimates from the FE Poisson model that examines the effect of restrictions and heat exemptions. Column (1) reports the coefficients from a model that utilizes the entire sample, where the dependent variable is export value, and the coefficients of interest are those on the county and state restriction variables. Column (2) includes the coefficient estimates from the second specification in which the regressor of interest is the heat exemption variable and its effect on poultry exports. In this second model, we utilize state-to-country level exports that occurred under a restriction, as heat exemptions are relevant when a ban is imposed. We report the exponentiated coefficients in Appendix S1.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Full Sample | Restriction = 1 |

| County restriction | −0.178* | - |

| (0.101) | ||

| State restriction | −0.914*** | - |

| (0.281) | ||

| Pct of slaughter plants restricted in state | −0.00160 | 0.00362 |

| (0.00470) | (0.00687) | |

| Turkey | 1.66e-07 | 1.10e-07 |

| (1.92e-07) | (2.95e-07) | |

| Broiler | −2.30e-07* | −1.12e-07 |

| (1.36e-07) | (4.53e-07) | |

| Duck | −1.63e-06*** | −5.47e-07 |

| (2.99e-07) | (2.14e-06) | |

| Heat exemption in place | 0.992*** | |

| (0.243) | ||

| Constant | 7.167*** | 5.012*** |

| (0.00540) | (0.204) | |

| Observations | 100,908 | 7259 |

| State FE | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | No |

| Month FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

- Note: Cluster standard errors in parentheses ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

- Abbreviation: FE, fixed effects.

We find state-level restrictions on U.S. poultry meat and products have a statistically significant and negative effect on export value (Table 4). More specifically, a state restriction is associated with a 60% decline in poultry export value.6 Conversely, county-level restrictions have a smaller, statistically significant effect on real export value—restrictions at the county/zone level are associated with a 16% decline in exports. We apply a Wald test to the null hypothesis that the coefficients on country and state restrictions are equivalent. We reject the null hypothesis () indicating that the coefficients are not equal. The statistically and economically significant effect of these restriction suggests that the geographic granularity of restrictions is an important determinant of whether these HPAI-related bans would have a detrimental effect on U.S. poultry exports.

In addition, the number of broilers and ducks infected with HPAI has a small but statistically significant effect on poultry export value. An increase of 100,000 broilers and ducks in commercial flocks is associated with a 2.3% and 1.6% decline in poultry export value, respectively. A 100,000 increase in confirmed detections may seem large; however, recent confirmed detections of HPAI in commercial broiler operations had over 60,000 birds affected each (USDA-APHIS, 2023).7 Lastly, in the second estimation, we find that a heat exemption would result in a 170% increase in export value when a restriction is in place. This increase suggests that heat exemptions can lessen the effect of a restriction, allowing some poultry products to continue with exportation. This finding is similar to Thompson (2018), in which the authors found no statistically significant trade effects on products such as prepared/preserved chicken meat because 57% of countries that imposed a trade restriction did not impose a restriction on cooked meat products during the 2014–2015 HPAI outbreak.

DISCUSSION

The possibility of HPAI transmission from U.S. poultry flocks to trading partners presents a documented and WOAH-recognized negative externality from trade (Radin et al., 2017; WOAH, 2024). More refined trade restrictions tailored to disease spread can mitigate biological risk and allay food safety concerns with a much smaller economic impact than coarse restrictions with broad geographic scopes.

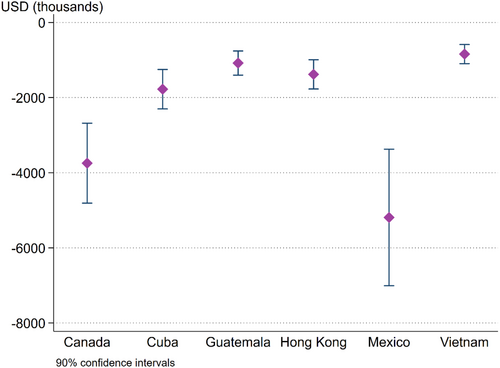

The coefficient estimates on state- and county-level restrictions suggest that confirmed detections of HPAI directly impact U.S. poultry exports. However, the lack of high statistical significance on the county-level restrictions does not allow us to exclude the possibility that these restrictions have no impact. The statistical significance of the coefficient on state-level restrictions and the statistically significant difference between the trade effects of county and state-level trade restrictions lead us to reject the possibility that state-level restrictions do not disrupt trade flows. To determine the benefit of localized restrictions, we compare the difference between predicted, average monthly export values, assuming countries had opted state-level restrictions instead of county-level and predicted, average monthly export values holding restrictions constant. We find the difference to be negative for the top six destinations for U.S. poultry, suggesting state-level restrictions would have reduced export flows. These countries all currently have county-level restrictions, and broader geographical restrictions at the state level would have resulted in average monthly losses ranging from $842,000 to $5,190,000 from each top trading partner in 2022 (Figure 5). Similarly, when countries adopt policies, such as heat exemptions and limit the extent to which geographical restrictions apply to certain poultry products, we find a statistically significant increase in export value.

Source: Model predictions

.A readily available vaccine does not exist for the HPAI virus that has circulated among wild and domesticated birds in the United States since 2022. The potential persistence of HPAI increases the value of understanding the economic gains of regionalization to decision-makers. The range of monthly gains from county-level regionalization described above provides a reasonable expectation of future gains, but the actual, realized gains will depend on disease prevalence, adjustments in biosecurity, and the evolution of the virus itself. We estimate an annual average avoided losses from county- rather than state-level restrictions of $16,128,000 in 2023 dollars. If HPAI becomes endemic (or persists for a very long time) and the gains from county-level regionalization follow their recent annual averages, then the expected net present value of all gains realized after 2023 would be over $293,236,364 in 2023 dollars, assuming the discount rate is the U.S. Federal Reserve's primary credit rate (5.5%). If these losses were only avoided in the 5 years following 2023, then the estimated avoided losses would be $68,871,148. This valuation suggests there are significant economic gains from regionalization and help inform the expectations surrounding these monetary benefits during the remainder of this and possible future outbreaks.

State-level trade restrictions markedly reduce exports by 60%. While we cannot observe intranational product flows, many more poultry products must be consumed locally, frozen, or shipped to neighboring states. The displacement of these products likely introduces additional costs not fully captured by wholesale or retail prices. By contrast, county-level restrictions are associated with a reduced export value of less than 16%, introducing far fewer adjustment costs along the supply chain.

CONCLUSIONS

HPAI continues to affect backyard and commercial operations, making the 2022 outbreak the longest and most geographically expansive animal health emergency in the United States. In 2022–23, approximately 77.3 million birds were affected across commercial operations in 47 states. In response to the outbreak, trading partners have imposed trade restrictions on U.S.-origin poultry meat and products that vary in length and geographical coverage. During the most recent outbreak, negotiating efforts among USDA-APHIS and foreign trading partners have resulted in more localized and county-level restrictions than in prior outbreaks. In this paper, we explore how trade restrictions with different levels of regionalization (county vs. state restrictions) might have heterogenous effects on U.S. poultry exports in 2022 and 2023.

We find that county-level restrictions are associated with a 16% decline in poultry export value, while state-level restrictions reduce export value by 60%. This disparity suggests that USDA-APHIS efforts to negotiate for more localized restrictions can result in export gains, as state-level restrictions are shown to have a larger detrimental, negative effect on poultry export value. However, more research on the effects of trade restrictions and regulations on meat trade is needed to better inform economic outcomes and the continuation of bilateral trade during animal health emergencies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. The authors thank the editor, Gopinath Munisamy, for his insightful comments. We also extend our gratitude to Jerry Cessna, Utpal Vasavada, Andrew Muhammad, and Amanda Countryman for helpful discussions and comments.