Early flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing after mechanical thrombectomy in stroke patients

Abstract

Objective

The aims of the study were to (1) characterize the findings of flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) in stroke patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy (MT); (2) analyse the screening performance of the Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA); and (3) study the impact of FEES-defined dysphagia on 3-month outcomes.

Methods

This single-centre study was based on a local registry of consecutive acute ischaemic stroke patients undergoing MT during a 1-year period. Patients received FEES within 5 days of admission regardless of the result of dysphagia screening. We compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without FEES-defined dysphagia. We collected 3-month modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and individual index values of the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-iv). Using univariable and multivariable regression analyses we predicted 3-month outcomes for presence of dysphagia and for FEES-defined dysphagia severity.

Results

We included 137 patients with a median age of 74 years, 43.1% were female, median NIHSS was 12 and successful recanalization was achieved in 92.7%. Stroke-associated pneumonia occurred in 8% of patients. FEES-defined dysphagia occurred in 81% of patients. Sensitivity of the SSA as a dysphagia screening was 67%. Presence of dysphagia and increasing severity of dysphagia were independently associated with increasing 3-month mRS score. Increasing dysphagia severity dysphagia was independently associated with lower EQ-5D-iv.

Interpretation

Early FEES-defined dysphagia occurs in four in every five patients undergoing MT. SSA has a suboptimal dysphagia screening performance. Presence of dysphagia and increasing dysphagia severity predict worse functional outcome and worse health-related quality-of-life.

Introduction

Dysphagia is one of the most frequent complications of acute stroke. Its frequency varies according to the screening and diagnostic methods used, and has been reported in up to 78% of patients.1 The presence of dysphagia after stroke is not only a marker of stroke severity, but it is also a predictor of poor long-term functional outcome and likelihood of institutionalization in a nursing or residential home.2 One of the most severe complications of dysphagia in stroke patients is the occurrence of pneumonia, which occurs in 14% of patients3 and significantly influences outcomes and healthcare costs.4

Dysphagia screening tests are widely used in the acute phase of stroke in stroke units and may be followed by a comprehensive clinical swallowing assessment and, eventually, additional instrumental techniques such as videofluoroscopic swallowing study or flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES).1 The performance of bedside dysphagia screening tests in stroke patients has been evaluated by comparing their results with the results of a comprehensive clinical swallowing assessment and/or instrumental techniques.5 One of the screening tests with a better overall performance is the Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA), which reached a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 90% for detection of dysphagia.5, 6 Validation studies of dysphagia screening tests were performed in unselected populations of stroke patients, and there is concern that the screening performance of bedside tests in patients with the more severe form of ischaemic stroke (i.e. with large vessel occlusion) may be suboptimal. Mechanical thrombectomy (MT), with or without intravenous thrombolysis, has become the standard of care for acute stroke patients with large vessel occlusion in the last decade.7 There are few studies addressing the frequency and characteristics of dysphagia and the performance of dysphagia screening tests in this group of patients, and there are still open questions related to the optimal strategy of swallowing assessment.8, 9 Current international guidelines for the diagnosis of post-stroke dysphagia recommend a detailed dysphagia assessment for stroke patients who fail a dysphagia screen and for patients who present risk factors for post-stroke dysphagia.10 A detailed dysphagia assessment, including comprehensive clinical swallowing assessment and instrumental swallowing assessment, allows not only to identify the presence of dysphagia and the risk of aspiration, but is also able to further characterize the type and severity of dysphagia and to provide dietary recommendations.

While early accurate identification and characterization of dysphagia in ischaemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion is of paramount importance to guide management, it may also provide prognostic information concerning medium-term outcome11, 12 and quality of life. It is well known that the severity of dysphagia is associated with decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL) independently of the aetiology of dysphagia.13 However, the factors influencing HRQoL in stroke survivors are multiple and complex, and little is known about the contribution of early dysphagia for prediction of quality of life after stroke.

The aims of this study were to (1) characterize the findings of FEES in stroke patients who underwent MT; (2) analyse the screening performance of the SSA in this group of patients; and (3) study the impact of FEES-defined dysphagia on 3-month clinician- and patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a single-centre retrospective study based on a prospective registry of consecutive acute ischaemic stroke patients undergoing emergent endovascular treatments. We identified all patients who underwent MT during a 1-year period (July 2021–June 2022), and selected patients who received FEES within 5 days of admission. Our standard acute stroke pathways, acute diagnostic workup, patient selection, intravenous thrombolysis protocol, MT technique and post-MT treatment follow national and international recommendations.14 In our centre, general anaesthesia for MT is the routine standard anaesthetic strategy, and we aim for extubation immediately after the procedure if there are no clinical contraindications (e.g. respiratory or cardiocirculatory instability, predicted prolonged reduced vigilance, malignant infarct and need for early neurosurgical treatment). Based on our observation of a high frequency of dysphagia in patients with large vessel occlusion undergoing MT,15 we adapted our criteria for performing FEES in the routine clinical care: beginning in July 2021, we systematically aimed to perform FEES within the first 5 days after admission in every patient undergoing MT, unless there were contraindications, the patient was receiving palliative treatment or the patient did not consent to the exam. FEES was performed in these patients regardless of the result of the initial dysphagia screening.

We collected the following information from the patients´ clinical records: demographic information, information on comorbidities and vascular risk factors, baseline stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, NIHSS), baseline Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS)16 or posterior circulation ASPECTS17 (pcASPECTS, for large vessel occlusions of the vertebrobasilar circulation), treatment with intravenous thrombolysis (alteplase is routinely used in our centre), site and laterality of large vessel occlusion, achievement of successful recanalization (defined as a revised thrombolysis in cerebral infarction [TICI] score of 2b, 2c or 3),18 door-to-recanalization time, occurrence of symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage (sICH, defined as an intracerebral haemorrhage occurring within 48 h after endovascular treatment and associated with an increase of ≥4 points in NIHSS or death), occurrence of stroke-associated pneumonia (probable or definite, according to the definition of the Pneumonia in Stroke Consensus Group)19 and stroke aetiology. Post-stroke 3-month outcomes were assessed in person or via telephone by experienced study nurses as part of the information routinely collected for the local registry. Functional outcome after 3 months was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale, where a score of 0–2 represents functional independence. Quality of life after 3 months was assessed using the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version (EQ-5D).20 To quantify the HRQoL based on the EQ-5D, index values were calculated for each patient based on the individual scores in each of the EQ-5D domains using the eq5d package in R (version 4.2.2). The EQ-5D index values were calculated using a country-specific value set which was previously established by the time trade-off method and represents the preferences of the German adult population.21 A predefined index value of 0 was attributed to patients who died during the first 3 months after MT. Per definition, an index value of 1 is considered a perfect health state and negative index values are considered health states worse than death. The mean EQ-5D index value for the general adult German population based on the trade-off method is 0.938.22

Dysphagia screening and flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing

Dysphagia screening was routinely performed by trained nurses using SSA,6 which was usually performed 24 h after extubation, mainly to avoid sedation-related reduced vigilance. Patients were given three trials of teaspoonful of water and subsequently a half a glassful of water, and signs of coughing, choking, breathlessness, wet/gurgly voice, prolonged oral phase, drooling or throat clearing were observed. If no such signs were observed, SSA was considered normal.

We aimed to perform FEES in all patients within 5 days after MT, regardless of the result of SSA. FEES was performed according to a local protocol by experienced speech and language therapists and/or neurologists accredited according to the accreditation program of the European Society for Swallowing Disorders.23 All FEES exams and reports are routinely reviewed by an experienced neurologist. Reasons for not performing FEES within 5 days in patients undergoing MT were systematically documented. Performance of FEES within 24 h of extubation was generally avoided because of possible residual sedation-related reduced vigilance and possible unstable cardiorespiratory or neurological condition, which could result in further invasive or operative treatments. After the initial assessment of the anatomy and function (including observation at rest, elevation of the soft palate, phonation and saliva management), patients received different food consistencies according to the local protocol, starting with puree consistency, followed by thin liquid consistency and solid consistency. Mixed and thick liquid consistencies were tested at the discretion of the therapist. The Yale Pharyngeal Residue Severity Rating Scale (YPRSRS, Table S1) for residues in the valleculae and piriform sinuses,24 the Penetration Aspiration Score (PAS, Table S2)25 and the presence of premature bolus spillage are systematically reported and were collected from the FEES reports. Predominance of residues in the valleculae was defined as a total YPRSRS sum (all consistencies) greater in the valleculae than in the piriform sinuses, and predominance of residues in the piriform sinuses was defined as a total YPRSS sum (all consistencies) greater in the piriform sinuses than in the valleculae.26 The severity of swallowing dysfunction was categorized in a four-grade FEES-based dysphagia score: 0 = no relevant dysphagia; 1 = mild dysphagia; 2 = moderate dysphagia; and 3 = severe dysphagia.27 Presence of dysphagia was defined as a FEES-based dysphagia score of 1–3.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, the distribution of continuous variables was tested for normality. Results for continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]), and results for categorical variables are presented as number (percentage). The diagnostic performance of SSA for the identification of patients with dysphagia or at risk of aspiration was compared with FEES as the reference, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated. The group of patients without FEES-defined dysphagia was compared to the group of patients with FEES-defined dysphagia using chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests as adequate. The presence of dysphagia (any severity) and the FEES-based dysphagia severity scale were analysed for prediction of functional 3-month outcome and for prediction of EQ-5D index values at 3 months. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses (using functional independence at 3 months as the dependent variable), univariable and multivariable ordinal regression analyses (using ordinal mRS as the dependent variable) and univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses (using EQ-5D index values as the dependent variable) were performed. Odds ratios (OR), β-coefficients and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated. The co-variates included in the multivariable models were variables which could theoretically influence the results and known to be predictors of outcome after stroke (age, sex, baseline clinical stroke severity, baseline severity of early ischaemic changes in computed tomography, intravenous thrombolysis, achievement of successful recanalization, door-to-recanalization time and sICH).28 The threshold of statistical significance was set at an alpha value of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0.1.0).

This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.29 Retrospective studies based on the local registry of patients with acute ischaemic stroke were approved by the local ethics committee (approval references 335/15) and, because of the retrospective nature, the ethics committee waived the need for patient-signed consent.

Results

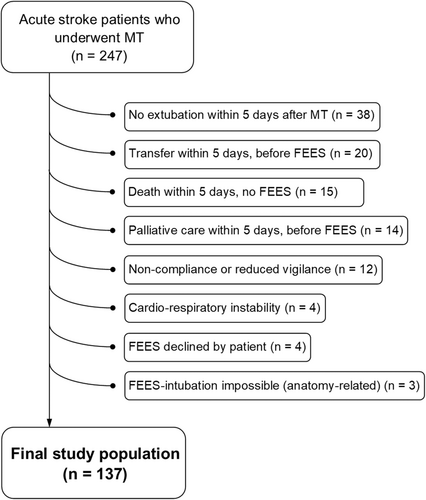

Among a total of 247 patients who underwent MT during the study period, the final study population included 137 patients who underwent FEES during the first 5 days after admission. Among the 110 patients who did not undergo FEES within 5 days of admission and were therefore excluded from the study, the most frequent reasons for not performing FEES were intubation and ventilation needed during the first 5 days (n = 38); transfer to another hospital/department within 5 days, before FEES (n = 20); death within 5 days and no FEES (n = 15), and initiation of palliative care within 5 days, before FEES (n = 14) (Fig. 1). Patients who were excluded from the final study population presented significantly more severe strokes, more frequently developed sICH and stroke-associated pneumonia, had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality and less frequently presented functional independence at 3 months (Table S3). Median age of the final study population was 74 years (IQR 62–83) and 43.1% were female. Median NIHSS was 12 (IQR 7–16), median ASPECTS/pcASPECTS was 9 (IQR 8–10) and the most frequent site of large vessel occlusions was M1 (39.4%) followed by M2 (24.1%) and carotid-T (11.7%). Additional intravenous thrombolysis was administered in 46.7% of patients and successful recanalization after MT was achieved in 92.7% of patients.

Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing and SSA findings

More than half of the included patients underwent FEES within the first 48 h of admission (n = 72, 52.6%), and three-fourths of patients underwent FEES within the first 72 h (n = 104, 75.9%). Dysphagia according to FEES was present in 111 of 137 patients (81.0%): 43 patients had mild dysphagia (31.4%), 51 patients had moderate dysphagia (37.2%) and 17 patients had severe dysphagia (12.4%). The findings of FEES in the study population are presented in Table 1. Silent aspiration was present in 43 patients (31.4%), and occurred predominantly for thin liquid consistency (29.9%). Median PAS scores were higher for thin liquid consistency (5, IQR 2–8) than for puree or solid consistencies (1, IQR 1–1). Premature bolus spillage and predominance of residues in the valleculae were among the main findings and occurred in 73.0% and 65.0% of patients, respectively. Total or partial nasogastric tube feeding was recommended in 23 patients (16.8%).

| Study population (n = 137) | |

|---|---|

| FEES-based dysphagia severity scale | |

| 0 (no relevant dysphagia) | 26 (19.0) |

| 1 (mild dysphagia) | 43 (31.4%) |

| 2 (moderate dysphagia) | 51 (37.2%) |

| 3 (severe dysphagia) | 17 (12.4%) |

| Worst PAS (median, IQR) | 5 (2–8) |

| Aspiration (any consistency) | |

| Aspiration (symptomatic and silent) | 65 (47.4%) |

| Silent aspiration | 43 (31.4%) |

| Premature bolus spilling (any consistency) | 100 (73.0%) |

| Predominance of residues in the valleculae | 89 (65.0%) |

| Predominance of residues in the piriformes sinuses | 5 (3.6%) |

| Puree consistency | |

| PAS (median, IQR) | 1 (1–1) |

| Silent aspiration | 3 (2.2%) |

| YPRSRS 4–5 | 37 (27%) |

| Thin liquid consistency | |

| PAS (median, IQR) | 5 (2–8) |

| Silent aspiration | 41 (29.9%) |

| YPRSRS 4–5 | 19 (13.9%) |

| Solid consistency | |

| PAS (median, IQR) | 1 (1–1) |

| Silent aspiration | 0 |

| YPRSRS 4–5 | 31 (22.6%) |

- IQR, interquartile range; PAS, penetration-aspiration score; YPRSRS 4–5, moderate to severe residues in the Yale Pharyngeal Residue Severity Rating Scale.

From a total of 137 patients, 132 had with available information on dysphagia screening (SSA), and 75 of these patients (56.8%) had abnormal findings. The sensitivity of SSA using FEES as reference was 67.0% for detection of dysphagia of any severity, 78.8% for detection of moderate to severe dysphagia and 76.7% for detection of aspiration. Among the 57 patients with normal SSA, 10 patients presented silent aspiration (17.5%). The diagnostic performance of SSA using FEES as reference for detection of dysphagia and aspiration is presented in Table 2.

| Dysphagia (any severity) | Moderate to severe dysphagia | Aspiration (any consistency) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 67.0 | 78.8 | 76.7 |

| Specificity (%) | 84.6 | 65.2 | 59.7 |

| Positive predictive value (%) | 94.7 | 69.3 | 61.4 |

| Negative predictive value (%) | 38.6 | 75.4 | 75.4 |

Comparison of patients with and without FEES-defined dysphagia

The comparison of the groups of patients with no relevant dysphagia and patients with dysphagia is presented in Table 3. Patients with FEES-defined dysphagia (of any severity) were older (77 vs. 61 years, p < 0.001), more frequently presented coronary heart disease (32.4% vs. 7.7%, p = 0.011) and had a different distribution of the site of arterial occlusion (p = 0.041), with non-significant numerically higher frequency of M2, carotid T, basilar artery posterior cerebral artery and tandem occlusions. Patients with FEES-defined dysphagia less frequently received intravenous thrombolysis (42.3% vs. 65.4%, p = 0.034) and had longer median door-to-recanalization times (139 vs. 110 min). The distribution of aetiology was also different between the two groups (p = 0.032), with non-significant numerically higher frequency of cardioembolic aetiology in patients with FEES-defined dysphagia. Stroke-associated pneumonia only occurred in the group of patients with FEES-defined dysphagia but the difference did not reach statistical significance (9.9% vs. 0%, p = 0.094).

| No dysphagia (n = 26) | Dysphagia (n = 111) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61 (54–76) | 77 (65–83) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 10 (38.5) | 49 (44.1) | 0.598 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 20 (76.9) | 91 (82.0) | 0.554 |

| Diabetes | 11 (42.3) | 33 (29.7) | 0.216 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 16 (61.5) | 58 (52.3) | 0.392 |

| Smoking | 0.133 | ||

| Active smoking | 9 (34.6) | 19 (17.1) | |

| Past smoking | 1 (3.8) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 2 (7.7) | 36 (32.4) | 0.011 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 10 (5–15) | 12 (7–16) | 0.232 |

| Baseline glucose | 117 (109–141) | 119 (104–141) | 0.771 |

| Baseline ASPECTS/pcASPECTS | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | 0.642 |

| Arterial territory of the occlusion | 0.167 | ||

| Carotid circulation | 25 (96.2) | 96 (86.5) | |

| Vertebrobasilar circulation | 1 (3.8) | 15 (13.5) | |

| Site of arterial occlusion | 0.041 | ||

| M1 | 13 (50.0) | 41 (36.9) | |

| M2 | 5 (19.2) | 28 (25.2) | |

| Carotid-T | 0 | 16 (14.4) | |

| Tandem occlusion | 2 (7.7) | 8 (7.2) | |

| Basilar artery | 0 | 8 (7.2) | |

| Posterior cerebral artery | 1 (3.8) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Other | 5 (19.2) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Laterality of large vessel occlusionb | |||

| Left-sided | 13 (52.0) | 48 (49.0) | 0.787 |

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 17 (65.4) | 47 (42.3) | 0.034 |

| Successful recanalization | 26 (100.0) | 101 (91.0) | 0.112 |

| Door to recanalization time (minutes) | 110 (89–158) | 139 (111–180) | 0.030 |

| Symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage | 1 (3.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0.260 |

| Stroke associated pneumonia | 0 | 11 (9.9) | 0.094 |

| Stroke aetiology | 0.032 | ||

| Cardioembolism | 10 (38.5) | 65 (58.6) | |

| Atherosclerotic large vessel disease | 6 (23.1) | 21 (18.9) | |

| ESUS | 8 (30.8) | 17 (15.3) | |

| Dissection | 2 (7.7) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Other causes or multiple causes | 0 | 7 (6.3) | |

| Failed standardized swallowing assessmenta | 4 (15.4) | 71 (67.0) | <0.001 |

- a Standardized swallowing assessment available for 132 patients.

- b Excluding patients with occlusions in vertebrobasilar territory.

Functional outcome and health-related quality of life at 3 months

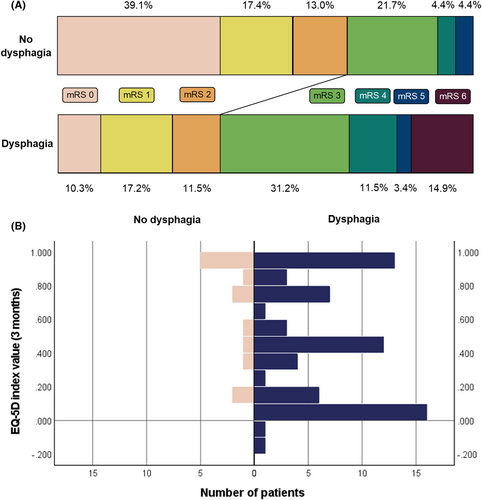

Information on functional outcome at 3 months was available for 110 patients, of which 13 patients had died. Distribution of 3-month mRS according to the presence of dysphagia is presented in Fig. 2A. EQ-5D index values at 3 months were available in 97 patients, and the distribution of EQ-5D index values according to presence of dysphagia is presented in Fig. 2B. Mean EQ-5D index value for all patients was 0.573 (standard deviation = 0.378). Although the presence of dysphagia of any severity was not independently associated with 3-month functional independence or with EQ-5D index values at 3 months, it was independently associated with a 2.8-time increased likelihood of increasing 1 point in the 3-month mRS score (OR = 2.86, 95% = 1.08–7.57, p = 0.034), indicating higher likelihood of worse functional outcome (Table 4). Each 1-point increase on the FEES-based dysphagia severity scale was independently associated with a 1.9-time increased likelihood of increasing 1 point in the 3-month mRS score (common OR = 1.92, 95%CI = 1.28–2.87, p = 0.002), and it was also independently associated with lower EQ-5D index values at 3 months (β-coefficient = −0.09, 95%CI = −0.16 to −0.01, p < 0.001), indicating lower HRQoL (Table 4).

| Dysphagia (any severity) | FEES-based dysphagia severity scale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | p | β-coefficient (95%CI) | p | Odds ratio (95%CI) | p | β-coefficient (95%CI) | p | |

| 3-month functional independence | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.28 (0.11–0.75) | 0.012 | – | – | 0.54 (0.35–0.83) | 0.005 | – | – |

| Adjusteda | 0.48 (0.15–1.59) | 0.231 | – | – | 0.62 (0.37–1.03) | 0.063 | – | – |

| mRS score at 3 monthsb | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 4.22 (1.78–10.00) | 0.001 | – | – | 2.07 (1.42–3.02) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Adjusteda | 2.86 (1.08–7.57) | 0.034 | – | – | 1.92 (1.28–2.87) | 0.002 | – | – |

| EQ-5D index value at 3 months | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | – | – | −0.28 (−0.46 to −0.10) | 0.003 | – | – | −0.14 (−0.21 to −0.06) | <0.001 |

| Adjusteda | – | – | −0.11 (−0.30 to 0.08) | 0.253 | – | – | −0.09 (−0.16 to −0.01) | <0.001 |

- a Adjusted to age, sex, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score/posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, intravenous thrombolysis, successful recanalization, symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage and door-to-reperfusion time.

- b Commons odds ratio indicate the likelihood of worsening 1 point on the modified Rankin Scale.

Discussion

One of the main conclusions of our study is that, in ischaemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion undergoing MT, early dysphagia defined by FEES within 5 days of admission is present in four in every five patients. The likelihood of finding post-stroke dysphagia is higher when instrumental testing is used, in comparison with isolated dysphagia screening and with isolated comprehensive clinical swallowing assessment.1 There are relatively few studies which systematically assessed swallowing in acute ischaemic stroke patient cohorts using FEES. In these cohorts the prevalence of dysphagia varied between 61% and 93%.8, 30-32 FEES-confirmed aspiration occurred in almost half of the patients in our study population, and it was found in 45%–81% of patients in previous studies.30-33 There is, however, a significant selection bias in studies using instrumental assessment of swallowing in acute stroke patients, which can influence not only the prevalence of dysphagia and aspiration risk but also the specific findings of swallowing impairment.5 Prolonged intubation, reduced vigilance, non-compliance, medical contraindications to FEES (such as respiratory instability, cardiocirculatory instability, impending cerebral herniation and active upper respiratory tract bleeding),34 early death or palliative care are not rare in acute stroke patients, limit the instrumental assessment of swallowing, and explain why our final study population had less severe strokes and less frequently had complications such as sICH and stroke-associated pneumonia. Therefore, we hypothesize that the prevalence of early dysphagia in non-selected ischaemic stroke patients undergoing MT is even higher than the one we found. Likewise, the timing of swallowing testing may also be a determining factor, because fluctuations and spontaneous or therapy-related improvements in swallowing function are frequent during the first weeks after stroke.35, 36

Dysphagia screening using SSA in this population of patients showed a relatively poor sensitivity for dysphagia (67%) and for aspiration (77%) because, as a screening test, it should be able to identify almost all patients with dysphagia or at risk of aspiration. Bedside screening tests typically perform better for the screening of aspiration than for the screening of dysphagia in acute stroke patients, with sensitivities for aspiration ranging from 49% to 100% in studies using FEES or videofluoroscopic swallowing study as reference.5 The finding that, in this cohort, 17.5% of patients with normal SSA presented silent aspiration also prompts the question of what is the optimal dysphagia screening and diagnostic strategy in patients with large vessel occlusion who underwent MT. The goal of this study was not to analyse different dysphagia screening methods, and we cannot exclude the possibility that other screening methods have better screening performance than SSA for this specific population of patients. In a recent study of stroke patients undergoing MT and/or thrombolysis, the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS) identified dysphagia in about 90% of patients in the first 72 h after reperfusion therapy,9 which could suggest a better sensitivity for this screening method. However, this study had a small study population (n = 26), and no comprehensive clinical or instrumental swallowing assessment which could serve as a reference for the analysis of the screening performance of GUSS was available. We argue that, given the high frequency of dysphagia, relatively high frequency of aspiration and relevant proportion of patients with a normal screening test who present silent aspiration, a direct clinical comprehensive swallowing assessment followed by additional instrumental diagnostic technique (e.g. FEES) should be considered in this population of patients. This suggestion is supported by a recent study in acute stroke patients demonstrating that the performance of FEES induced an adjustment of oral diet in almost 70% of patients who had previously received a dietary recommendation based on a clinical non-instrumental swallowing assessment.37

Another important conclusion of our study is that the severity of early dysphagia predicts not only clinician-reported functional outcome but also patient-reported outcomes 3 months after large vessel occlusion ischaemic stroke and MT. These associations were demonstrated to be independent of other known important outcome predictors in ischaemic stroke such as age, clinical severity, extent of early ischaemic signs in computed tomography and occurrence of sICH. Both the presence of FEES-defined dysphagia of any severity and an increasing FEES-defined dysphagia severity are associated with an increased functional disability, as measured by mRS at 3 months. The current study confirms previous evidence demonstrating an association of dysphagia with functional outcome after ischaemic stroke2, 11, 15, 38 and also the previous findings by Warnecke et al showing that increased severity of early dysphagia predicted poorer 3-month functional outcome in a selected population of stroke patients.39 Our study demonstrates for the first time, that in stroke patients undergoing MT, an increasing dysphagia severity, as assessed by FEES within 5 days of hospital admission, is also independently associated with worse global HRQoL at 3 months. Although there are several scales available which evaluate dysphagia-related quality of life in patients with dysphagia,40 we specifically aimed to study a validated patient-reported measure of global quality of life in stroke patients with or without dysphagia at follow-up. The reasons why increasing early dysphagia severity is associated with medium-term HRQoL independently of initial stroke severity, are complex and probably mediated by persistence of dysphagia symptoms and continued need of dietary adaptations in a subgroup of patients, suboptimal nutritional status and consequent impaired immune status even in patients who recover from dysphagia, increased incidence of aspiration pneumonia, need for ongoing rehabilitation, need for continued support from care persons and health professionals, increased anxiety related to risks of suffocation and severe coughing, lower self-esteem related to dysphagia-related disruption of previous life style and social habits, among others.41-43

We expected to find an increased prevalence of stroke-associated pneumonia in patients with FEES-defined dysphagia, but we found no significant statistical difference between groups with and without dysphagia in our study. We believe that the main reason for this is the small size of our study population and the lack of statistical power. Another contributor to the lack of significant difference between the two groups is the relatively low frequency of stroke-associated pneumonia in our selected study population (8%, compared with a pooled overall frequency of 14% in unselected acute ischaemic stroke cohorts3).

Conducting a swallowing screening or an instrumental swallowing assessment in patients with left-sided cerebral ischaemic lesions and aphasia may be limited by impairment of language comprehension, which may result in poorer swallowing performance not primarily related to swallowing impairment. On the other hand, it is known that right-sided cerebral lesions can also impair swallowing by causing buccal hemineglect44 and swallowing apraxia.45 There is no definite evidence pointing to a higher frequency of post-stroke dysphagia in left-sided or right-sided supratentorial ischaemic lesions, and different phases of swallowing appear to be differentially lateralized.46, 47 In our study, distribution of stroke laterality in the anterior circulation was similar in groups of patients with and without dysphagia, but we did not explore in more detail neuroanatomical correlations with impairment of each swallowing phase.

FEES findings such as worse swallowing performance for thin liquid consistencies, and frequency of premature bolus spillage (73%) and silent aspiration (31%) are in agreement with the previous literature. Penetration and aspiration in stroke patients are long known to be more frequent with liquid consistencies in comparison to other food consistencies, which is a hallmark for neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia.48 Warnecke et al found that premature bolus spillage is an important factor contributing to dysphagia in patients with supratentorial ischaemic stroke, and that was the leading mechanism in the impairment of swallowing safety and efficacy in 73% of patients.26 Among patients with stroke who underwent FEES, silent aspiration was found in every third to fourth patient.48, 49 We found a relatively high prevalence of predominance of residues in the valleculae (65%), which was found to be the leading mechanism in the impairment of swallowing safety and efficacy in the majority of patients with Parkinson's disease and in only 4% of stroke patients according to Warnecke et al.26 This comparison has limited validity, because the characteristics of ischaemic stroke patients, timing of FEES and prevalence of residues in the valleculae were not described in this study. However, our study suggests that predominance of residues in the valleculae alone may not be a good discriminating characteristic to differentiate between different dysphagia aetiologies.

The main limitations of the study include the relatively small population size, the retrospective design (which led to missing information), the exclusion of 110 of patients because of impossibility to perform FEES within 5 days of admission and consequent selection bias, missing information on 3-month functional outcome in 20% of patients, missing information on 3-month HRQoL in 29% of patients and unknown swallowing status at 3 months. The strengths of this study lie on the identification of all consecutive acute ischaemic stroke patients undergoing MT, systematic documentation of the reasons for not performing FEES within 5 days of admission, availability of detailed clinical information and detailed findings of the FEES, and analysis not only of clinician-reported outcomes but also of validated patient-reported HRQoL outcome measures.

In conclusion, early dysphagia defined by FEES occurs in four in every five acute ischaemic stroke patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. SSA has a suboptimal dysphagia screening performance in this subgroup of stroke patients. The presence of FEES-defined dysphagia and increasing severity of dysphagia are independently associated with worse 3-month functional outcome and with decreased 3-month health-related quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JP, CJW, AR, BSW. Data curation: JP, TM, BM, BM, AD, JB, AW, ST. Formal analysis: JP. Methodology: JP, CJW, AR, BSW. Resources: JBS, MW. Supervision: ON, CJW, AR. Validation: ON, CJW, AR. Visualisation: JP. Writing original draft preparation: JP. Writing reviewing and editing: all authors.

Acknowledgement

None. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

This study received no funding.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, for research purposes and according to institutional guidelines.