Sugarcane

Abstract

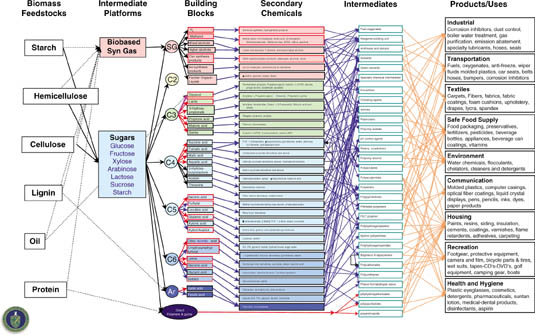

As more than 70% of the sugar harvested for human consumption is derived from sugarcane, improving sucrose content, biomass yield, and resistance to pests and diseases remains an important focus of traditional breeding programmes. In addition, genetic engineering research has supported the introduction of specific traits and facilitated further understanding of complex physiological pathways in the plant. Transgenesis has allowed diversification of output traits so that a range of sugars, biopolymers, neutraceuticals, industrial enzymes, and pharmaceuticals can be produced by the plant. Sugarcane is considered as a critical component of our bioenergy future and is currently a major feedstock for ethanol production. Significant advances in associating putative biological functions to sugarcane genes have been achieved by the Brazilian SUCEST project. Future genetic improvement of sugarcane will rely on a better understanding of metabolic control and flux, cellular compartmentation and availability of metabolites, and the ability to identify potential and crucial targets for genetic engineering.

1 Introduction

1.1 History, Origin, and Distribution

Sugarcane is a large grass of the genus Saccharum, tribe Andropogoneae, family Poaceae. Modern sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) cultivars are interspecific hybrids derived from a hybridization process involving Saccharum officinarum (or “noble cane”) and Saccharum spontaneum (wild cane), followed by a series of backcrosses to the noble parent (Daniels and Roach, 1987).

The earliest known historical record of sugarcane and sugar is from Indian writings from 3000 to 3400 years ago. The generic name for sugarcane, Saccharum, originated from the Indian Sanskrit term “sharkara” for the crude sugary product obtained from the honey reeds. Dispersal of Indian sugarcane westward seems to have occurred during the first millennium BC. Soldiers of Alexander the Great are known to have carried it to Europe from India about 325 BC. Later, Greek and Roman writers were familiar with the concept of the Indian honey reed and its “honey” (sugar) product. The early history of sugarcane is covered by a number of authors, including Deer 1949 and Barnes 1964.

The origin of sugarcane is a complex question that is best discussed in relation to its taxonomy and distribution in Southeast Asia, the Indonesian Archipelago, and New Guinea. Different species likely originated in various locations with S. officinarum and Saccharum robustum in New Guinea, Saccharum barberi in India, and Saccharum sinense in China. Dispersal of S. officinarum over a period of thousands of years is believed to have occurred both into the Pacific Ocean area, and along the island chain into Asia, whilst the thinner Indian canes were developed and cultivated in the North India/South China region.

Initially, pieces of cane stalk would have been chewed to express the sweet juice, and chewing canes still provide a conveniently packaged form of energy food in many cultures. Juice extraction from the stalk, and concentrating it by drying or heating to produce a crude sugary product, must have been developed in a rudimentary form at least 3000 years ago. The art of sugar manufacture took longer to develop, probably in India and perhaps less than 2000 years ago. Deer 1949 considered that Nestorian Christian monks at the mouth of the Euphrates river were the first to refine the crude raw product into a form of “white” sugar about 450 AD.

The Mediterranean sugar industry was the first major one in Europe, and began about the time of the Arabian conquest of Egypt in 640 AD. They spread it across North Africa and into Spain by 750 AD, where it was important for many years, with 30000ha under cane by 1150 AD. By the early 1500s AD, cane was carried by the Spanish to the Caribbean and the Americas, and by the Portuguese to West Africa and Brazil. And so the worldwide sugarcane industry was born.

Prior to the 20th century, the world sugarcane industry was dependent on the noble canes (S. officinarum) and the cane from India and China (S. barberi and S. sinense, respectively) (Sreenivasan et al., 1987). These canes were characterized by high sucrose levels and low fiber contents, but were susceptible to several pests and diseases, notably sereh disease (Arceneaux, 1965). Sugarcane breeding and selection became a directed, ongoing process following the observation in 1858 that sugarcane panicles produce viable seed (Stevenson, 1965). The Dutch established a breeding and selection program in 1888 in Java to incorporate the disease resistance, hardiness, and tillering capacity of S. spontaneum into S. officinarum germplasm. Interspecific crosses were made between S. officinarum and the wild S. spontaneum (which was resistant to sereh) (Stevenson, 1965). The resultant hybrids were continually backcrossed to S. officinarum in a process called nobilization (Stevenson, 1965). This effort resulted in the release of the first of the nobilized hybrid cane cultivars, POJ2725 and POJ2878 in 1921. These two early cultivars served as the foundation in the pedigree of nearly all locally developed and adapted modern sugarcane cultivars worldwide (Moore, 2005). Nobilization became established as a method of retaining the desirable qualities of S. officinarum, retaining the hardiness and disease resistance of S. spontaneum, while diluting the negative effects of wild germplasm (Berding and Roach, 1987).

Currently, sugarcane is widely grown for sugar production in many tropical and subtropical countries (with a minimum of 600mm of annual rainfall) in South, Central, and North America, the Caribbean, Africa and adjacent islands, Southern Asia and Australasia.

1.2 Evolution, Taxonomy, Cytological Features, and Genome Size

Mukherjee 1957 coined the term “Saccharum complex” to describe a large, closely related genera (Erianthus sect Rhipidium, Miscanthus, Sclerostachya, Narenga), which are considered to be involved in the evolution of cultivated species of Saccharum. The phylogenetic relationships within the Saccharum complex have been debated for many years (Daniels and Roach, 1987; Irvine, 1999). A long discourse on how the various species may have evolved is provided by Daniels and Roach 1987.

-

S. officinarum L.: sweet, juicy, thick stalk garden cane, initially in New Guinea

-

S. barberi Jesw.: sweet, thin stalk Indian canes

-

S. sinense Roxb.: sweet, thin stalk Chinese canes

-

S. edule Hassk.: edible inflorescence garden cane, New Guinea, Melanesia

-

S. spontaneum L.: very thin, hardy wild canes, low sugar, New Guinea and southern Asia

-

S. robustum Brandes & Jeswiet ex Grassl: tall, harder, thick stalk wild canes, a little juice and sugar, New Guinea and eastern Indonesia

Modern commercial sugarcane cultivars are highly heterozygous, complex polyploid, and aneuploid hybrids, often with four of the above species of Saccharum in their ancestry. Cytological studies showed that nobilization is characterized by asymmetric chromosome transmission (Bremer, 1961). In a cross between S. officinarum (2n = 80) as the female parent and S. spontaneum (2n = 40–128) as the male parent, S. officinarum generally transmits two haploid chromosome sets while S. spontaneum transmits one. This 2n+n transmission is continued up to the second backcross. A consequence of this is that modern cultivars have chromosome numbers ranging from 2n = 99–130 (Bremer, 1961). In addition, commercial sugarcane cultivars have complex polyploid (10–12 copies of the genome) and aneuploid (100–120 chromosomes) genomes. In polyploids such as sugarcane, the haploid chromosome number (1C value = n) is not the same as the monoploid number (= x) (Butterfield et al., 2001). The monoploid genome size for S. officinarum (x = 10) is approximately 926Mbp (mega base pair), and for S. spontaneum (x = 8) 760Mbp (Butterfield et al., 2001). This base genome number is roughly double the monoploid genome size of rice (415Mbp) and similar to that of Sorghum bicolor Moench (760Mbp) (Butterfield et al., 2001).

1.3 Economic Importance: Production, Utilities, Economic Attributes, and Industrial Uses

Sugarcane is cultivated for its high rate of sucrose accumulation, ease of propagation via vegetative stem cuttings and multiple harvests from a single planting. It is a principal crop in tropical and subtropical regions, with a production estimate of over 1.3 million metric tons of sucrose per annum. It provides approximately 70% of the world's sugar (FAO, 2006).

Sugarcane has long been recognized as one of the most efficient crops in terms of converting solar energy into biomass (Alexander, 1973). It is one of the most effective photosynthesizers in the plant kingdom, able to convert 2% of incident solar radiation into plant biomass. It is the second largest contributor (10–12%) of dietary carbohydrate to humans after the cereals. Sugar processing meets the needs of both high-income consumers (e.g., refined white and specialty sugars) and low-income domestic consumers (e.g., the production of jaggery in India or panela in Colombia, where cane juice is boiled to make cakes of brown sugar). By-products of sugar milling such as bagasse, molasses, furfural, furfuryl alcohol, dextran, and diacetyl (O'Reilly, 1998) have several uses. For example, bagasse (a fibrous residue after sugar extraction) can be used to fuel boilers in the sugar mills, to generate electricity for the local power grid, to manufacture paper, and as an animal feed. Molasses are used in syrups and animal feed and as a substrate for ethanol production.

Sugarcane is considered as a critical component of our bioenergy future as: (i) sugarcane is already used in the production of ethanol, produced by fermentation and distillation of sugars. Currently, Brazil is the world's largest producer of sugarcane ethanol (Moreira, 2000). Ethanol can be blended with gasoline (gasohol) or diesel (biodiesel or dieselhol); (ii) production of energy, such as ethanol, from sugars is more efficient than production from grains, in both cost for joule produced and energy input/output efficiency. For each unit of fossil energy input to the sugarcane agro-industrial system, nine units of renewable energy output (ethanol plus surplus bagasse) result, compared to less than 2 units resulting from grains, such as maize; and (iii) sugarcane is ranked first among all other crops for biomass production (FAO: http://www.fao.org; Moreira, 2006). As a perennial crop, it has more advantages for biofuels production than annual crops. It is more efficient at solar energy conversion, and it can be harvested annually for a number of years without replanting.

1.4 Traditional Breeding: Breeding Objectives, Tools and Strategies, and Achievements

The objectives of sugarcane breeding programs around the world are to produce cultivars with improved characteristics such as increased cane yield, higher sucrose content, pest and disease resistance, tolerance to abiotic stress, and improved ratooning ability. Focused breeding programs have led to significant contributions to characters such as those listed above (Hogarth, 1976; Nuss, 2001).

Crossing of two parents is the first step in producing and selecting a new cultivar. If pollen and seed production do not occur naturally, as is the case in sugarcane growing areas with latitudes above 15° north and south, crossing is conducted in photoperiod glasshouse facilities where day length and temperature can be manipulated (Brett, 1974). Extensive evaluation of the progeny from the crosses is undertaken. The selection process consists of several different stages and usually takes 10–14 years to release a variety. This prolonged period before a new sugarcane variety can be commercially released is largely due to the reliance of the selection process on phenotypic characters. At each stage, clones with unsuitable characters are discarded and the performances of selected clones are evaluated in larger plots (Parfitt, 2005).

Due to the narrow genetic base of modern varieties (Hogarth, 1987), sugarcane breeders have tried to exploit the genetic variation within the Saccharum complex, which shows great variation for a range of traits of interest to the breeders, such as sugar content, tolerance to drought and cold, pest and disease resistance, uprightness, fiber content, tiller number, stalk size and strength, low suckering, easiness to detrash (suitability for mechanical, green harvest), and ratooning ability. Breeders have used S. spontaneum, Miscanthus sinensis, Erianthus arundinaceus, and Erianthus rockii in introgression initiatives.

S. spontaneum. In the development of modern sugarcane cultivars, an average of only 15–25% of chromatin is derived from S. spontaneum (D'Hont et al., 1995), due primarily to the limited number of S. spontaneum genotypes used (Berding and Roach, 1987). Only two genotypes of S. spontaneum were used in the initial crosses made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in India and Java (Martin, 1996). S. spontaneum has been considered as a source of positive alleles for traits involved in adaptation to different climatic conditions and for disease and insect resistance. Dunckelman and Breaux 1972 studied the agronomic habits of 32 apparently mosaic-resistant S. spontaneum genotypes to ascertain their potential utilization as breeding material, and found a genotype (US 56-15-8) particularly sweet, with a juice Brix reading of 11.5%. The characterization of sugar composition of S. spontaneum genotypes from the World Collection of Saccharum (Miami, Florida) also indicated that this species is a potential source of positive alleles for sugar content (Tai and Miller, 2001). These results were confirmed by da Silva et al. 2007 in a study involving molecular markers to test if alleles with positive effects for sucrose content could be found in S. spontaneum. Expressed sequence tags (ESTs) involved in sucrose accumulation from the metabolism of complex carbohydrate pathway (da Silva et al., 2007) were used to develop molecular markers. By targeting four functionally characterized sugar metabolism candidate genes to a set of 50 S. spontaneum genotypes showing variation in sugar content, S. spontaneum-specific polymorphic markers were identified. These markers are not present in commercial sugarcane genotypes and may therefore be used for tagging positive S. spontaneum alleles for introgression into commercial sugarcane genotypes. Efforts to introgress these alleles were made in 2005 at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Sugarcane Unit in Houma, Louisiana, with a cross involving the commercial cultivar HoCP00-950 and the S. spontaneum genotype MPTH97-216, from Thailand.

M. sinensis. A difficulty in breeding sugarcane for stress tolerance is the trade-off between stress tolerance and yield (Ming et al., 2006). Developing varieties adapted to a wider range of climatic regimes could improve sugarcane production in water-restricted and/or colder regions. Sugarcane with increased water use efficiency and tolerance to drought or cold temperatures are critical selection criteria for that goal. Another way to overcome this difficulty would be to identify alternative alleles contributing to stress tolerance in the Saccharum complex and introgress these into commercial germplasm. Even though the water use efficiency of sugarcane is high, substantial amounts of water are required to maintain maximal growth and productivity. Since irrigation of sugarcane fields is limited, and irrigation of biomass crops is unlikely to be economic, it is important to identify genotypes that are tolerant to water stress. Screening with Paraquat (methyl viologen) for drought tolerance in sugarcane (Ming et al., 2001b), wheat, and barley (Altinkut et al., 2001) has proved to be a rapid and practical screening method, in conjunction with chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, for identifying and characterizing genetic variation in sugarcane water stress tolerance (Ming et al., 2006).

Miscanthus species are exceptionally tolerant to low temperature and drought and are among the few plants in temperate climates that use the C4 photosynthetic pathway (Naidu et al., 2003). In a study comparing drought tolerance of different Miscanthus species (M. sacchariflorus, M. giganteus, and M. sinensis), M. sinensis was the only one that did not show senescence caused by water deficit (Clifton-Brown et al., 2002). M. sinensis retained all of its green expanded leaf area irrespective of water supply, showing its complete resistance to senescence. Similarly, when commercial varieties, breeding lines and seedlings of sugarcane and Miscanthus were exposed to freezing temperatures for at least 2h in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas in 2004, leaf damage was observed on all sugarcane plants, but not on Miscanthus × Saccharum sp. hybrid seedlings (Figure 1). Miscanthus species also have high cellulose fiber content and are considered a potential energy crop by the European Union (EU) (Clifton-Brown et al., 2004).

Miscanthus sinensis × Saccharum sp. hybrid seedlings showing cold tolerance under subfreezing field conditions

If the superior drought and cold tolerance and high fiber of Miscanthus could be combined with the photosynthetic capacity of commercial sugarcane, it would be possible to produce a low-input, high-biomass, drought- and cold-tolerant energy crop. As M. sinensis (2n = 2x = 38) is closely related to sugarcane, it produces viable hybrids when crossed with sugarcane (Grassl, 1967; Lo et al., 1986), and can be seen as a source of stress tolerance genes for introgression purposes. Atienza et al. 2003 have shown that it is feasible to develop a marker-assisted selection program for biomass production in Miscanthus using quantitative trait loci (QTL) to detect markers for traits such as diameter, height, and panicle size. These QTLs could assist in introgression work.

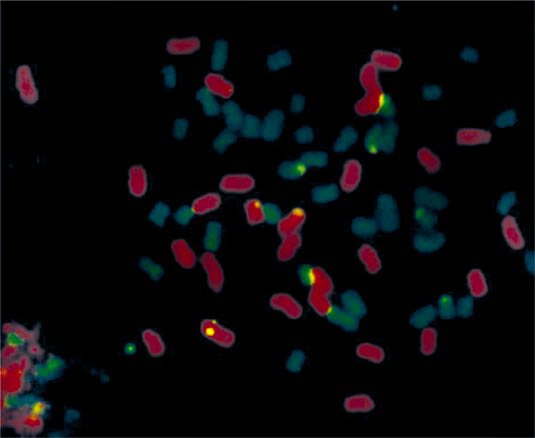

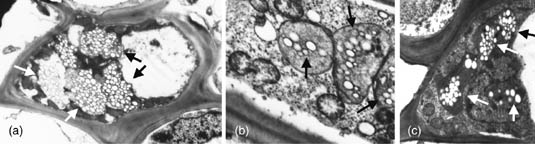

Erianthus species. The Erianthus genus contains eight species (Aitken et al., 2007) and is also a potential donor for stress-resistant genes. E. arundinaceus has several traits desirable to sugarcane breeders such as tolerance to drought and waterlogging, high resistance to Pachymetra root rot, vigor, and good ratooning performance (Berding and Roach, 1987). Many attempts have been made to generate sugarcane × E. arundinaceus hybrids. In situ hybridization analysis of progeny from some of these crosses indicated that the introgressions were successful (D'Hont et al., 1995; Figure 2). However, only one appears to have been successful in producing fertile offspring. Cai et al. 2005 describe the intergeneric hybridization of two populations using the S. officinarum Badilla as the female parent in both crosses with pollen from three different E. arundinaceus clones from Hainan, China. They also describe the backcrossing of the F1 hybrid, YC96-40 with sugarcane cultivar CP84-1198 to generate the backcross 1 (BC1) population, demonstrating the fertility of the intergeneric hybrid. Molecular markers were used to confirm both the introgression into the F1 and BC1 populations and the parentage of the BC1s.

Chromosomes from a root-tip cell of an intergeneric hybrid fluorescing after genomic in situ hybridization. Saccharum officinarum chromosomes are green and Erianthus arundinaceus chromosomes are red [Reproduced with permission from George Piperidis, BSES Limited]

E. rockii. A species originating in the Yunnan, Sichuan, and the Tibetan regions of China, has good vigor, cold and drought tolerance, and good ratooning ability. E. rockii was recently reported by Aitken et al. 2007 to have been successfully used as the male parent for intergeneric hybridization with (1) Vietnam-niuzhe (S. officinarum) and (2) interspecific hybrid Fiji (S. officinarum × S. spontaneum). Using amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP), Aitken et al. 2007 showed that all of 10 screened E. rockii × S. officinarum crosses were true intergeneric hybrids, but that 9 of 10 of the E. rockii × Fiji crosses were selves of the E. rockii female parent and only one was a true introgression. Further analysis showed that there was a (n + n) transmission of gametes.

1.5 Limitations of Conventional Breeding and Rationale for Transgenic Approaches

-

Commercial sugarcane cultivars possess different proportions of chromosomes, complex recombinational events, and varying chromosome sets (aneuploidy) (Sreenivasan et al., 1987). This genomic complexity brings difficulties in applying conventional plant breeding for cultivar improvement. In addition, conventional breeding is a multistage, laborious, and time-consuming process requiring 10–14 years to develop a new cultivar. A single fault, such as disease susceptibility in an otherwise elite cultivar, could cause the cultivar to be abandoned. Conventional breeding approaches to correct such faults in an existing cultivar are impractical in sugarcane, due to the genetic complexity of cultivars (Birch and Maretzki, 1993). The capacity to introduce specific genes by transgenic approach, without major genetic reassortment following crossing, could be used to rescue flawed cultivars (Birch and Maretzki, 1993). For example, the successful production of sugarcane plants resistant to leaf scald disease was achieved by transgenic approach (Zhang et al., 1999).

-

Although breeding efforts in sugarcane have been successful in increasing cane production, only limited success has been achieved recently in increasing sugar content. For example, there has been no increase in sugar content over the last 40 years in Australian sugarcane (Bonnett et al., 2004b). In the USA, Legendre 1995 reported that the average sucrose content of new candidate varieties decreased 3.5% on the fifth cycle of recurrent selection, as compared to the previous cycle, indicating that a limit has been reached for this trait. The QTL analysis of interspecific F1 populations also indicated that modern sugarcane cultivars have a limited (biased subset) population of genes controlling sugar content (Ming et al., 2001b). In contrast, metabolic engineering of sugarcane through transgenic approaches could improve sugar content. For example, transgenic sugarcane with doubled sugar content was achieved when attempting to produce isomaltulose in sugarcane (Wu and Birch, 2007).

-

Production of novel products in sugarcane is not possible by conventional breeding. In contrast, metabolic engineering through transgenic approaches could produce new products, such as alternative sugars, biopolymers, pharmaceuticals, and high-value proteins. For example, successful production of sorbitol (Chong et al., 2007), isomaltulose (Wu and Birch, 2007), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (pHBA) and biodegradable polymer (McQualter et al., 2005; Petrasovits et al., 2007) has been achieved in transgenic sugarcane, which cannot be achieved through conventional breeding.

-

Conventional breeding allows transfer of traits and genes only between sexually compatible species. Hence, transfer of traits from noncompatible species is impossible. In contrast, transgenic approaches allow insertion of novel genes from sexually noncompatible plants/organisms, enable expression of native genes at different levels in specific tissues or under novel developmental patterns of expression.

-

The number of traits to be considered when selecting for variety development is determined by the degree of genetic linkage among those traits. If linkages are rare, several traits can be selected simultaneously. In the case of sugarcane the extent of those linkages is still uncertain (Ming et al., 2006). Recent advances in molecular marker-assisted selection and transformation technologies can alleviate the problem. Thus, genetic transformation by modern molecular techniques (see in Section 2) has the potential to enhance a host of traits including sugar, pest and disease resistance, tolerance to drought and cold, vigor, plant architecture and fiber, and to produce alternative products such as biopolymers and isomaltulose in sugarcane.

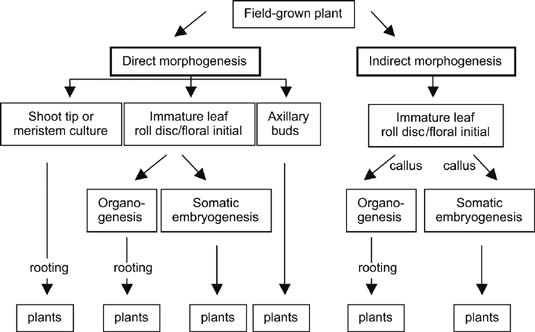

Figure 3

Figure 3Summary of direct and indirect morphogenic pathways for sugarcane regeneration. In the routes where the rooting event is noted, external application of growth hormones is usually required for root production

2 Development of Transgenic Sugarcane

Sugarcane is a prime candidate for the application of genetic engineering, as single characters can be introduced into the complex genetic background of elite commercial clones to correct negative factors, such as disease susceptibility. Successful genetic engineering requires a reliable tissue culture system and efficient transformation methods. Sugarcane was one of the first monocotyledonous crop plants used successfully for establishment of tissue cultures (Barba and Nickell, 1969; Nickell and Maretzki, 1969), regeneration of plants (Heinz and Mee, 1969), and isolation of protoplasts (Maretzki and Nickell, 1973; Nickell and Heinz, 1973).

2.1 Tissue Culture and Transformation

The early established robust tissue culture/regeneration system of sugarcane became a foundation for efficient genetic transformation of this crop. The explant most frequently used for transformation experiments in sugarcane is embryogenic callus. This callus is produced from the culture of immature leaf whorls immediately above the apical meristem. The whorls are sliced into thin (2–3mm) transverse sections and cultured on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with an auxin (usually 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and sucrose, and subcultured every 3–4 weeks. Prolific compact embryogenic callus is produced within 2 months. However, this varies with different clones and needs to be optimized for the genotype being used.

2.1.1 Regeneration of plants

Sugarcane has a well-established history of in vitro regeneration that began in the late 1960s (Heinz and Mee, 1969). Regeneration of sugarcane can occur via several different pathways (Figure 3) (reviewed by Snyman, 2004; Lakshmanan, 2006; Lakshmanan et al., 2005). The pathways of regeneration by somatic embryogenesis or organogenesis have been well characterized and documented (Ho and Vasil, 1983; Guiderdoni and Demarly, 1988; Taylor et al., 1992). For the regeneration of transgenic plants in vitro, the route of morphogenesis is dependent on the explant targeted for DNA delivery. Criteria for explant choice are: (i) a large number of regenerable cells and (ii) maintenance of regenerative capacity during the selection procedure.

Where embryogenic callus is used as the recipient material for foreign DNA, regeneration is via somatic embryogenesis (Bower et al., 1996; Falco et al., 2000) or organogenesis (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996). Although transgenic plants have been successfully generated via indirect morphogenesis, limitations include the amount of time taken to regenerate a transgenic plant (36 weeks from DNA delivery to glasshouse transfer) (Bower et al., 1996; Snyman et al., 2000) and the incidence of somaclonal variation as evidenced in agronomic variability when plants are evaluated in the field (Grof and Campbell, 2001; Vickers et al., 2005b).

Alternative tissue targets for transgene delivery have been sought, such as exposed apical meristems from axillary buds followed by shoot morphogenesis (Gambley et al., 1993, 1994; Manickavasagam et al., 2004), leaf roll discs (Snyman et al., 2000, 2001) and pre-emergent inflorescences (Snyman et al., 2006) followed by direct somatic embryogenesis. Although these methods have resulted in transformed plants in a reduced time frame compared to protocols employing indirect embryogenesis, determination of phenotypic fidelity in the field has yet to be published.

2.1.2 Transformation methods

Initial work on sugarcane transformation targeted protoplasts as recipient cells and DNA delivery was via polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Chen et al., 1987) or electroporation (Rathus and Birch, 1992). However, neither technique resulted in the production of transgenic plants, as sugarcane regeneration from protoplasts is notoriously difficult. A significant milestone in sugarcane transformation was achieved when particle bombardment of embryogenic callus was reported and a protocol for recovery of transgenic plants was described (Bower and Birch, 1992). Embryogenic callus proved to be a reliable source of tissue for further refinement of microprojectile bombardment protocols and for the production of transgenic plants in several parts of the world (Bower et al., 1996; Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996; Snyman et al., 1996; Joyce et al., 1998; Ingelbrecht et al., 1999; Falco et al., 2000). In addition, Agrobacterium-mediated DNA delivery was also developed using embryogenic callus as recipient cells (Arencibia et al., 1998; Elliott et al., 1998; Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2003).

Microprojectile bombardment using a gene gun has been achieved using either the particle inflow gun (PIG) (Finer et al., 1992) or a BioRad device (Heiser, 1993). The principle of this transformation method is to coat either tungsten or gold particles with plasmid DNA containing the gene(s) of interest and to bombard these particles into embryogenic sugarcane callus using pressurized helium combined with a partial vacuum chamber. The first report of successful transformation of sugarcane suspension culture cells using the PIG gun was by Birch and Franks 1991 using the GUS (β-glucuronidase) reporter gene and kanamycin selectable marker gene, although no plants were regenerated. This approach was further refined by Bower and Birch 1992 and is now widely adopted for the production of transgenic sugarcane (Bower et al., 1996; Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1993, 1996; Franks and Birch, 1992; Snyman et al., 1996; Joyce et al., 1998; Ingelbrecht et al., 1999; Falco et al., 2000). Transformation efficiencies vary depending on genotype, quality of embryogenic callus, length of time spent in vitro, and selection regime employed, but most laboratories have developed a protocol that suits their requirements.

Explant type |

Transformation method |

Gene |

Selective agent (mgl−1) |

Escapes |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Callus |

Biolistic |

NptII |

Geneticin (45) |

Nil |

|

Callus |

Biolistic |

Bar |

BASTA (1-3) |

Yes |

Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996 |

Callus |

Agrobacterium |

Hph |

Hygromycin (25) |

Yes |

Arencibia et al., 1998 |

Callus |

Agrobacterium |

Bar |

Bialophos (1) |

Yes |

Elliott et al., 1998 |

Immature leaf whorls |

Agrobacterium |

Bar |

PPT (4) |

Yes |

Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998 |

Axillary meristem |

Agrobacterium |

Bar |

BASTA (5) |

Yes |

Manickavasagam et al., 2004 |

Callus |

Agrobacterium |

NptII |

Paromomycin (150) |

Nil |

Joyce et al., 2006a |

The desire to minimize transgene copy number and integration complexity, coupled with advances reported in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in other monocotyledonous crops (reviews by Cheng et al., 2004; Shrawat and Lorz, 2006; Wang and Ge, 2006), made this an appealing system to develop in sugarcane. Although not widely applied yet, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation using embryogenic callus and four different strains of Agrobacterium (Arencibia et al., 1998; Elliott et al., 1998; Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2003) and axillary buds with two strains (Manickavasagam et al., 2004) has been reported. Although it is difficult to compare transformation efficiencies between the above papers, it appears that pretreatment of the callus prior to Agrobacterium co-cultivation improves transformation efficiency (e.g., a 30min dehydration period). In addition, selection of a particular size of callus (1000μm) (Arencibia et al., 1998), and use of antinecrotic compounds (2mgl–1 silver nitrate; 15mgl–1 ascorbic acid (Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998) were reported to be advantageous. In both papers, Arencibia et al. 1998 and Enriquez-Obregon et al. 1998, the transgene copy number was 1–3. Elliott et al. 1998 applied no selection pressure for up to 6 weeks after co-cultivation. After this period, GFP (green fluorescent protein)-positive calli were visually selected and transferred to bialaphos at 1mgl–1. Two transgenic plants were regenerated that contained three and seven copies of the GFP gene, respectively.

More recently, transgenic plants were generated using axillary meristems of sugarcane (Manickavasagam et al., 2004). This novel approach resulted in a transformation efficiency of 49.6%. They used two strains of Agrobacterium, LBA4404 and EHA105. The plasmid pGA492 contained the nptII (neomycin phosphotransferase) gene driven by the nos (nopaline synthase) promoter and the bar and gus genes driven by cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. Selection was on 5mgl–1 bialaphos, applied immediately after the co-cultivation period. Transformation efficiency was greatest in both strains when co-cultivation period was for 3 days in the presence of 50μM acetosyringone. Thousands of plants were produced within 5 months. Although chimeric plants were reported, the incidence was eliminated in secondary shoots after five rounds of selection on Basta®-containing medium. When these plants were transferred to the greenhouse and sprayed with herbicide, a total of 336 plants (clones of 10 independent transformation events) representing 50% of total plants screened, displayed herbicide resistance. Southern blot analysis on a small subset of these plants further confirmed the presence of 1–2 copies of the transgene in each plant.

2.1.3 Selection of transformed tissues

Studies on transgenic sugarcane for technology development have involved marker and reporter genes. The reporter genes used include GUS (Jefferson et al., 1987; Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004; Braithwaite et al., 2004), luciferase (luc) (Mudge et al., 1996b; Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004), maize anthocyanin regulatory elements (R and C1) (ANT) (Ludwig et al., 1990; Bower et al., 1996; Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004), and GFP (Elliott et al., 1998; Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004; Gnanasambandam et al., 2007; Petrasovits et al., 2007). Comparative studies by Bower et al. 1996 on the suitability of GUS, luc, and ANT as reporter genes for transient assays in sugarcane transformation indicated that the ANT system is the most suitable reporter system. ANT expression is visible within 8h after bombardment and steadily increases in intensity up to 48h after bombardment. The expressing cells remained visible in the target tissue for 2–3 weeks, before fading or being overgrown. In addition, the results were not confounded by background ANT activity. In contrast, the main disadvantage of using the GUS reporter gene is that the conditions for detection of gene activity are lethal to plant cells and therefore the transformed event is subsequently lost. Detection of both luc and GFP genes require specialized camera and/or detection systems. In addition, GFP detection is confounded by autofluorescence of the callus and chlorophyll in green plant tissues. However, the power of confocal laser scanning microscopy allows precise visualization of fluorescent signals within a narrow plane of focus, and the reconstruction of three-dimensional structures from serial optical sections (Haseloff et al., 1997). This is an advantage of GFP over both GUS and luc (Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004).

The most widely adopted stable-integration antibiotic marker used for sugarcane transformation is the aphA2 Escherichia coli Tn5-derived nptII. The first successful application of the nptII-based selection system was reported as a step-wise incremental procedure using geneticin (Bower and Birch, 1992). This formed the foundation for subsequent protocols utilizing geneticin (also known as G418) (Bower et al., 1996; Falco et al., 2000; Snyman, 2004) or paromomycin (Joyce et al., 2006a) as the selective agent (Table 1). Less widely used is the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hph) gene with selection on 20mgl–1 hygromycin (Arencibia et al., 1998; Carmona et al., 2005).

The first paper reporting herbicide resistance in sugarcane also described a selection procedure incorporating a herbicidal agent, bialaphos (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996). The bar and pat genes from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and Streptomyces viridochromogenes, respectively, encode the phosphinothricin acetyltransferase enzyme that leads to detoxification of phosphinothricin and its derivatives that are ingredients in some commercial herbicides. Selection using herbicides has been used widely, although each laboratory has to determine empirical regimes for selection of different explants and genotypes and formulations of active ingredients differ (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996; Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998; Manickavasagam et al., 2004) (Table 1).

The use of the above genes, in addition to selection of transformed cells and plants, has been beneficial in generating information about transgene expression and stability in transgenic sugarcane (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996; Enriquez-Obregon et al., 1998; Leibbrandt and Snyman, 2003).

There is limited published work on the use of positive selection systems, such as the E. coli manA phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) gene, in sugarcane. The ubiquitous plant enzyme hexokinase converts mannose to mannose-6-phosphate (Man-6-P). Man-6-P is toxic to plants, but most plants lack PMI and are inhibited by the accumulation of Man-6-P. PMI catalyzes the reversible interconversion of Man-6-P and fructose-6-phosphate, thereby releasing the Man-6-P inhibition and making mannose available as a carbon source for the plant. This system was first demonstrated for transformation of potato, sugar beet, and maize (Bojsen et al., 1998, 1999) and since then it has been used successfully in a variety of other plant species. PMI has no adverse effects in acute mouse oral-toxicity tests, generates no detectable biochemical changes in mannose-associated pathways (Privalle et al., 1999), lacks many attributes known to be associated with allergens (Privalle, 2002), and may thus be considered as an ideal selection protein for plant transformation. For sugarcane transformation, calli were selected on media containing 3gl–1 mannose, in addition to the 20gl–1 sucrose present in the media (Jain et al., 2006). Plant regeneration was performed under the same level of selection. An increase of mannose from 1.5 to 3gl–1 for rooting improved the overall transformation efficiency. The PMI encoding gene, manA, was stably integrated and expressed in almost all of the transgenic lines.

Of the other nonantibiotic systems tested in sugarcane, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase was unsuitable, while selection incorporating arabitol showed up to 100-fold lower transformation efficiency. In addition, arabitol is expensive, making it a less desirable selection agent.

2.1.4 Promoters and termination sequences

The two main sources for promoters are from microorganisms (viral or bacterial) or from plants. In addition, there are a few synthetic promoters that have been constructed in the laboratory by combining regulatory and/or enhancer elements from different viral or plant promoters. What is lacking in sugarcane, and in monocots in general, is a promoter that functions as strongly as the CaMV 35S promoter does in dicots. Schledzewski and Mendel 1994 compared transient reporter gene expression in transgenic cells of barley, maize, and tobacco driven by maize polyubiquitin1 (Ubi-1), rice actin1, Emu, or CaMV 35S promoter. CaMV 35S promoter had the highest GUS activity in tobacco (316.71nmolh–1) compared to maize (9.88nmolh–1) and barley (1.22nmolh–1). In contrast, of the four promoters tested, the Ubi-1 promoter showed highest expression in both maize and barley cells, but not in tobacco. However, CaMV 35S in tobacco showed a promoter strength equivalent to 2.5- to 5-fold greater than Ubi-1 in maize (Table 2).

Promoter |

Reporter gene |

Transient expressiona |

Stable expressiona |

References |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

GUS |

Transient in leaf (after 48h) (nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein) |

Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1993 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi-1 Rice Act1 Emu CaMV 35S |

50.0 (1.00) 10.0 (0.20) 11.0 (0.20) 0.5 (0.01) |

||||||||

GUS |

Percentage of total foci |

Tang et al., 1996 |

|||||||

Total |

BS |

Meso |

Epi |

||||||

Maize Ubi-1 |

771 |

2% |

3% |

95% |

|||||

ScRbcs |

259 |

23% |

8% |

69% |

|||||

Luciferase |

(Fg lucμg−1 protein) 5–8-month-old plants Mean |

Hansom et al., 1999 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi1 Act1 Osa |

84000 (1.00) 1000 (0.12) 3000 (0.04) |

||||||||

Winter 96 |

Summer 96 |

Winter 97 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi-1 |

175 (1.00) |

125 (1.00) |

4500 (1.00) |

||||||

Osa |

25 (0.14) |

10 (0.10) |

70 (0.05) |

||||||

Emu |

5 (0.03) |

2 (0.02) |

200 (0.40) |

||||||

GFP |

Mature Leaf (ugmg−1 protein) Mean |

Schenk et al., 2001 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi-1 BSVCv |

1.5 (1) 4.5 (3) |

||||||||

GUS |

Transient (after 48h) (nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein) |

Stable (after 4 months) (nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein) |

Liu et al., 2003 |

||||||

Callus |

Leaf |

Callus |

Leaf |

||||||

Maize Ubi-1 |

1850 (1.00) |

613 (1.00) |

105 (1.000) |

48 (1.0) |

|||||

CaMV 35S |

62 (0.03) |

22 (0.04) |

5 (0.007) |

0 |

|||||

RiceUbiQ2 |

1231 (0.70) |

342 (0.60) |

70 (0.700) |

79 (1.6) |

|||||

GUS |

Transient in callus (nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein) |

Yang et al., 2003 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi-1 SEF1 SPRP SPRP2.4 |

0.6 0.8 0.9 0.5 |

||||||||

NPTII |

In vitro tissue culture plants (ng NptIImg−1 protein) |

Glasshouse plants (ng NptIImg−1 protein) |

Braithwaite et al., 2004 |

||||||

Callus |

Leaf |

Root |

Meristem |

Leaf |

Root |

||||

Maize Ubi-1 |

100 (1.0) |

50 (1.0) |

75 (1.0) |

45 (1) |

50 (1) |

50 (1) |

|||

SCBV (IMPs) |

100 (1.0) |

85 (1.7) |

80 (1.1) |

225 (5) |

240 (5) |

150 (3) |

|||

SCBV (IMHS) |

130 (1.3) |

100 (2.0) |

60 (0.8) |

250 (6) |

350 (7) |

180 (4) |

|||

GUS |

Stable callus (ng GUSmg−1 protein) Mean |

Wei et al., 2003 |

|||||||

Maize Ubi-1 ScUbi4b ScUbi9b |

1500 (1.0) 600 (0.4) 2000 (1.3) |

||||||||

- a Numbers in brackets are expression relative to that with the Maize Ubi-1 promoter

- b Sc—Sugarcane

2.1.4.1 Viral promoters

The viral promoter most frequently used in plant transformation is the CaMV 35S promoter. However, this promoter is not highly expressed in sugarcane (Table 2). Schenk et al. 2001 reported the isolation of two novel promoters from a DNA virus that infects banana (banana streak virus, BSV). The region of two BSV isolates (2105bp and 1322bp) upstream of the open reading frame (ORF) were labeled as Mys and Cav, respectively, and assessed for promoter activity in stably transformed sugarcane callus using GFP (sGFPS65T) as a reporter gene. Results of the promoter analysis showed that after 19 months growth, the plants transformed with the BSV-Cav construct showed greater than threefold higher activities than the maize Ubi-1 promoter (10.62μgGFPmg–1 total protein and 3.2μgGFPmg–1 total protein, respectively). In addition, this promoter appeared to be expressing in a constitutive manner. GFP accumulation was observed in vascular tissue, bundle sheath cells as well as leaf parenchyma and epidermal cells of sugarcane. Expression, however, was strongest in the parenchyma cells with all three promoters.

Promoters from a sugarcane-specific badnavirus (sugarcane bacilliform virus, SCBV) were cloned and tested using two marker genes (GUS or nptII) (Braithwaite et al., 2004). Three of the four promoters tested were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from sugarcane plants containing the virus while the fourth promoter was subcloned from an almost genome-length clone of SCBV. All four promoters were active in sugarcane, with the highest GUS expression present when the subcloned region of SCBV was used for promoter construction. When different parts of the plantlets were assessed for GUS expression (Table 2), the meristems of young plants had the highest levels, there was some in young leaves, but no expression in roots. When nptII expression was assessed in young in vitro plantlets, however, transgene activity was present in callus, leaves, and roots to a similar level (<0.01% of total soluble protein). Thus, the lack of GUS activity in the roots may be a consequence of poor penetration of the GUS substrates to the root region. Interestingly, when the nptII transgenics were grown to maturity in the glasshouse, the lines driven by the SCBV promoter showed a fivefold higher activity than the Ubi-1-driven plants (Table 2).

2.1.4.2 Plant-derived promoters

The maize Ubi-1 promoter (Christensen and Quail, 1996) is the most frequently used constitutive promoter for sugarcane transformation (Table 2) and its expression is usually higher than other plant-derived promoters (sugarcane Ubi and rice actin1). Expression of luc activity in sugarcane plants by maize Ubi-1 promoter ranged between 200 and 300000 relative light units (RLU) mg–1 protein compared to 200–2000 RLUmg–1 protein in actin1 lines (Hansom et al., 1999; Table 2). In addition, this expression was independent of copy numbers.

Using particle bombardment of sugarcane callus, Liu et al. 2003 showed that there was a 1.6-fold increase in GUS expression by the rice Ubi-2 promoter (mean = 78.6nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein) over the maize Ubi-1 promoter (mean = 47.6nmol 4-MUmin−1mg−1 protein). The GUS gene driven by CaMV 35S showed no expression in regenerated plants, and was <10% of that of ubiquitin promoters in transient expression analysis (Table 2).

Tang et al. 1996 compared the expression patterns of GUS, driven by promoters of two sugarcane ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate small subunit (Rubisco) genes (scrbcs-1 and -2), in transient assays. Both promoters directed expression in leaf tissues, but not in calli. Although the overall expression levels were lower when compared to the maize Ubi-1 promoter, scrbcs promoters drove higher expression in the photosynthetic cells, especially in the bundle sheath cells (Table 2). Stable expression in transgenic callus lines and regenerated plants also showed that scrbcs-1 promoter directed GUS expression in leaves, but not in calli.

Two sugarcane polyubiquitin gene promoters (sugarcane ubi4 and ubi9) were found to direct high levels of transient GUS expression in the following monocots: sugarcane, maize, sorghum, banana, pineapple, garlic, and rice cells (Wei et al., 1999, 2003). Both of these monocot promoters were also sufficient to drive GUS expression in cells of tobacco. In these transient assays, the activities of the two sugarcane promoters were comparable to the strong monocot promoter, maize Ubi-1 (Christensen and Quail, 1996). Similar to Ubi-1, sugarcane ubi4 was heat shock inducible in stably transformed sugarcane callus lines, but sugarcane ubi9 was not (Wei et al., 2003). The physiological difference between the two sugarcane ubiquitin promoters corresponded to a MITE (miniature inverted-repeat transposable element) insertion that is present in the putative heat shock elements of sugarcane ubi9 but not present in sugarcane ubi4. In transgenic sugarcane plants produced by particle gun bombardment, GUS expression from sugarcane ubi4 and ubi9 dropped to very low or nondetectable levels after plant regeneration. This drop in expression also occurred in Ubi-1 sugarcane lines. Nuclear run-on experiments showed the down-regulated transgenes continued to be transcribed at high levels, indicating that the lack of transgene expression was due to post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS). In contrast, sugarcane ubi9 drove high levels of expression in transgenic rice plants produced via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. This high level of expression continued after plant regeneration and was inherited in the T1 generation (Wei et al., 2003).

2.1.4.3 Synthetic promoters

The promoter Emu was synthesized by Last et al. 1991 and contains a truncated maize alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) promoter as well as several copies of the maize anaerobic responsive elements from the Adh gene. In addition, it contains the ocs-element of the octopine synthase gene from Agrobacterium. Comparative studies of GUS expression in sugarcane protoplasts using constructs with either the Emu or the CaMV 35S promoter showed a 50–100-fold increase in Emu-driven GUS expression over the 35S promoter (Rathus and Birch, 1992). However, Joyce et al. 1998 and Bower et al. 1996 found that the Emu promoter could not drive strong expression in mature sugarcane plants (Table 2).

Osa is another synthetic promoter, developed by CSIRO Plant Industry Australia, which consists of multiple octopine synthase (OCS) enhancer elements, the core region from the CaMV 35S promoter and untranslated leader sequence from maize transposable element Ac (Bower et al., 1996). Experiments in sugarcane using this promoter also showed much lower levels of gene expression than maize Ubi-1 (Table 2).

2.1.4.4 Terminator sequences

The most commonly used terminator sequences for transformation of sugarcane callus is the Nos terminator sequence from Agrobacterium. There are a few reports where the Agrobacterium octopine synthase gene (Ocs) terminator sequence has been used (Elliott et al., 1998). The studies have not compared the effect of terminator sequences on transgene expression in sugarcane; this is an area of research that has been neglected and warrants further investigation.

2.1.5 Activity, stability of inheritance, and silencing of transgenes

The high level of ploidy found in all sugarcane may have some important implications for transformation, which are not normally encountered when working with diploid species. For instance, increase in ploidy by genome duplication, which has been suggested to play an important role in angiosperm evolution (Stephens, 1951; Ohno, 1970; Blanc et al., 2000; Initiative, the Arabidopsis Genome, 2000; Paterson et al., 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005; Bowers et al., 2003; Vandepoele et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005b), is associated with a host of rapid responses, including loss and restructuring of low-copy DNA sequences (Song et al., 1995; Feldman et al., 1997; Ozkan et al., 2001; Shaked et al., 2001; Kashkush et al., 2002), activation of genes and retrotransposons (O'Neill et al., 1998; Kashkush et al., 2003), gene silencing (Chen and Pikaard, 1997a, b; Comai, 2000; Comai et al., 2000; Lee and Chen, 2001), and organ-specific subfunctionalization of gene expression patterns (Adams et al., 2003, 2004). Sugarcane appears to have undergone two such genome duplications in about the past 5 million years and these mechanisms may be especially important in providing raw material for evolutionary change. It is important to understand how stable the sugarcane genome is with respect to: (i) transposon activity; (ii) genome expansion or contraction; (iii) measuring the extent of gene silencing and alterations in gene expression; (iv) assessing in vitro regeneration systems for epigenetic variation in regenerated plantlets; and (v) designing transformation technologies to overcome the above constraints.

Molecular techniques for detection and characterization of transgenes with respect to integration pattern, copy number, and protein concentrations have been conducted and published (Bower et al., 1996; Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996). However, these analyses were carried out on sugarcane plants maintained in glasshouses. Field analysis to determine expression and stability of transgenes is important because of sugarcane's multiple vegetative crop cycles and reports of PTGS.

The transgenesis approach in sugarcane has targeted elite commercial cultivars. It would be advantageous to be able to use transgenic plants as parents in breeding programs especially when the desired trait is not present in the sugarcane gene pool. Transgene inheritance and segregation of the bar herbicide resistance gene and the hut Sorghum mosaic virus (SrMV) coat protein gene was tracked in progeny arising from conventional crosses made between transgenic and nontransgenic parents (Butterfield et al., 2002). The results demonstrated that transgenic plants can be used as parents in a sugarcane breeding program but screening progeny for a characteristic such as virus resistance that relies on PTGS mechanisms may have to be carried out after one vegetative cycle of growth after crossing.

PTGS is known to occur in sugarcane (Ingelbrecht et al., 1999) and is considered to be one of the factors limiting accumulation of recombinant proteins (Wei et al., 2003). It was thought that it could be reversed by retransformation with a gene encoding a viral suppressor of PTGS, such as HcPro from SrMV (Ingelbrecht et al., 2000) and P0 from sugarcane yellow leaf virus (ScYLV) (Wang et al., 2006, 2007). Despite the potential application in transgene silencing control, there are possible negative effects on endogenous gene regulation and virus susceptibility. Initial results indicate that there is no consistent correlation between the RNA expression levels of P0 or HcPro and the expression of a transgene and several miRNA-regulated endogenous genes. Further research is required to characterize the effect of these viral suppressors in transgenic sugarcane (Wang et al., 2006, 2007).

Sugarcane plants transformed via particle bombardment with GM-CSF (human cytokine granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor), contain numerous copies of transgenes with complex integration patterns as revealed by Southern blot hybridization (Albert et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2003). Multiple approaches have been evaluated for the introduction of single- or low-copy transgenes, to determine if these methods can reduce transgene silencing (Albert et al., 2004). These methods include the use of insert-only DNA for bombardment (Fu et al., 2000), Cre/lox site-specific recombination to resolve multiple transgene copies (Srivastava and Ow, 2001), and the Ac/Ds transposon system to direct transgene integration by transposition (Koprek et al., 2000, 2001). The use of linear expression cassette-only DNA was reported to produce a high frequency of low-copy transgene insertions in rice, with no evidence of silencing through the R4 generation (Fu et al., 2000). In contrast, most transgenic sugarcane lines produced by this method contained multiple transgene copies, with only three of 27 selected lines containing three or fewer copies (Wang et al., 2003). Cre/lox lines did contain fewer copies of the transgene as estimated by quantitative PCR (qPCR). However, accumulation of GM-CSF in the low-copy lines was not higher than in multicopy lines (Albert et al., 2004). In addition, a vector system was developed to allow direct plasmid to chromosome transposition using Ac/Ds in monocot cells. This should allow single-copy transposition lines to be produced in a single generation without sexual crosses (Albert et al., 2003). However, no increase in GM-CSF protein level was observed in the Ac/Ds lines.

2.1.6 Adverse effects on growth, yield, and quality

Most evaluation of transgene stability and expression patterns and performance of transgenic sugarcane plants in the field has been limited to a few lines (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996; Arencibia et al., 1999; Leibbrandt and Snyman, 2003). However, results of recent studies where a larger number of lines were tested (Gilbert et al., 2005; Vickers et al., 2005b) may influence future transgenic approaches.

Initial field trials demonstrated stable expression of a herbicide-resistant transgene over three rounds of vegetative propagation in a single transformant (Gallo-Meagher and Irvine, 1996; Leibbrandt and Snyman, 2003), but no agronomic measurements were taken in the first study. In the latter trial, no differences were found between the transgenic line and wild-type control in phenotypic characters such as stalk height and diameter, agronomic performance indicators such as sucrose yield and fiber content, and disease susceptibility ratings to smut and rust. However, in a field trial where 100 transgenic lines were compared for Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) resistance and yield characteristics, a considerable amount of variability for measured parameters was reported, which the authors attributed largely to the effects of the cultivar used and the tissue culture process (Gilbert et al., 2005; Vickers et al., 2005b). Similarly, preliminary data from metabolomic analysis, comparing leaves from nontransformed sugarcane with leaves from transgenic sugarcane lines producing polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), found that the vast majority of the variation was a tissue culture effect and was not from the insertion of the PHB metabolic pathway and the selectable marker genes (Purnell et al., 2007).

2.1.7 Subcellular targeting

Most transgene expression constructs used for sugarcane transformation result in production of foreign gene products in the cytosol, but important metabolic activities ranging from photosynthesis to sugar storage are carried out in other compartments. Hence, targeting proteins to subcellular compartments may be necessary for effective resistance to pest and diseases and efficient metabolic engineering in sugarcane. For example, for increased resistance to sugarcane leaf-scald disease, resistance gene products may need to be targeted to the plastids, as the albicidin toxin from the pathogen Xanthomonas albilineans blocks plastid DNA replication and chloroplast development. Similarly, for efficient conversion of sucrose to alternative carbohydrates such as starch and fructans, foreign proteins need to be targeted to the sugarcane vacuoles in mature stem parenchyma cells, where most of the sucrose is stored.

The ability to target recombinant proteins to the correct subcellular location using efficient and appropriate targeting signals is one of the most important requirements for sugarcane metabolic engineering. Various targeting signals have been successfully tested to target heterologous proteins to different subcellular compartments in sugarcane. The availability of visible reporters such as GFP in combination with a transient assay system in sugarcane leaves allowed the testing of the efficiency of various targeting signals with less time and resources (Gnanasambandam et al., 2007). While most of the tested signal sequences are from dicotyledons species, they were effective in the monocotyledon sugarcane. So far, targeting signals for vacuoles, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), plastids, mitochondria, and peroxisomes have been tested in sugarcane (McQualter et al., 2005; Petrasovits et al., 2007; Brumbley et al., 2006b; Gnanasambandam et al., 2007). In future, signals for other compartments and efficiency of signals will be determined.

2.1.7.1 Protein targeting to vacuoles

Sugar storage vacuoles occupy about 80% of the total tissue space in mature sugarcane stem and accumulate sucrose up to 500μmolg–1 fresh weight (Moore, 1995). Due to the potential to engineer synthesis of valuable compounds other than sucrose in sugarcane (e.g., alternative carbohydrates such as starch and fructans), the sugarcane vacuole is one of the important target compartments for metabolic engineering. However, targeting proteins to the sugarcane vacuoles remains a challenge and differs in several aspects compared to targeting to other compartments: (i) the sugarcane vacuolar compartment is highly dynamic in function, and is acidic as indicated by neutral red accumulation in most protoplasts isolated from sugarcane suspension cells and stem storage parenchyma cells (Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004). It is not known whether several vacuole types coexist in sugarcane cells with different pH and/or proteolytic activities. As a result, there may be several independent targeting mechanisms to different vacuole types in sugarcane; (ii) targeted proteins should be stable and functional in the vacuolar environment, engineered for the relevant pH and proteases. For example, when the N-terminal vacuolar targeting signal (NTPP) of potato patatin was used to target yeast invertase to the sugarcane vacuole, neither detectable amounts of invertase protein nor increased soluble acid invertase activity was observed (Ma et al., 2000). Similarly, fusion of NTPP from sweet potato sporamin to various reporter proteins resulted in substantial reduction or loss of enzymatic activity in transient expression assays and in transformed sugarcane cells (Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004); and (iii) protein targeting mechanisms to many compartments (e.g., peroxisomes, mitochondria, and ER) are highly conserved in eukaryotes. In contrast, protein targeting to the plant vacuole through the endomembrane system is different from the lysosomal and vacuolar targeting mechanisms of animals and yeast. While mammalian cells use mannose-6-phosphate mediated lysosomal targeting, yeast cells use N-terminal propeptides for vacuolar targeting. In contrast, plants employ three different types of targeting signals that are found either at the N-terminus or the C-terminus or within the mature polypeptide (Matsuoka and Neuhaus, 1999).

Two signals, the NTPP of sweet potato sporamin and sugarcane legumain, were reported to be efficient in targeting reporter proteins to the sugarcane vacuole (Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004; Rae et al., 2006). In contrast, the C-terminal signal from tobacco chitinase was inefficient in targeting a reporter protein to the sugarcane vacuole (Gnanasambandam and Birch, 2004). Using the NTPP of sporamin, metabolic engineering of vacuolar compartment to produce high-value isomaltulose has been demonstrated successfully (Wu and Birch, 2007). Vacuolar targeting of the sucrose isomerase using the NTPP of sporamin allowed high isomaltulose yields (up to 440μmolg–1 fresh weight) in sugarcane stems. In contrast, expression of a cytosolic form of the same enzyme caused stunting with reduced sugar accumulation. Interestingly, isomaltulose accumulated in storage tissues without any decrease in stored sucrose concentration, resulting in doubled total sugar concentrations in harvested juice (Wu and Birch, 2007) in vacuolar targeted lines. The transgenic lines with enhanced sugar accumulation also showed increased photosynthesis, sucrose transport and sink strength (Wu and Birch, 2007).

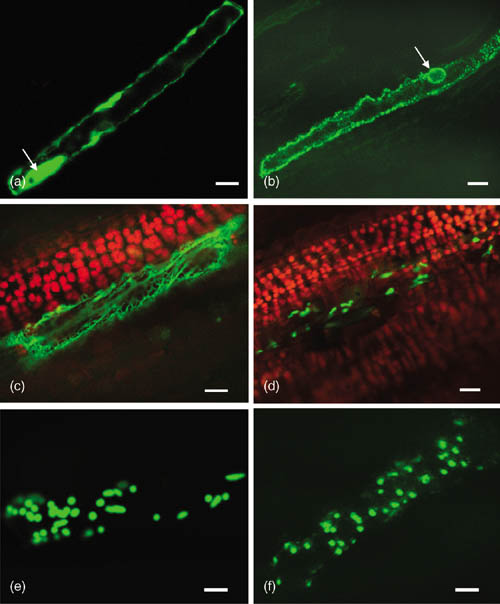

2.1.7.2 Protein targeting to plastids

The N-terminal plastid transit peptides of RbcS (rubisco small subunit) genes from maize and pea were used to target heterologous enzymes to sugarcane plastids to successfully produce p-hydrobenzoic acid (pHBA; McQualter et al., 2005) and polyhydroxybutyric acid (PHB biopolymer; Petrasovits et al., 2007). The transit peptides from tomato DCL (defective chloroplast and leaves) and tobacco RbcS genes were shown to target GFP to the sugarcane leaf proplastids (Gnanasambandam et al., 2007; Figure 4).

Confocal images of sugarcane leaf epidermal cells showing fluorescence of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in different subcellular compartments. Nontargeted GFP in the cytosol (a) and nucleus (arrow in a). ER-targeted GFP fluorescence in the ER (b, c; arrow in b shows perinuclear distribution). Plastid-, mitochondrial-, and peroxisomal-targeted GFP in the proplastids (d), mitochondria (e), and peroxisomes (f), respectively. All images show green channel GFP fluorescence except (c) and (d) that show merged images of green (GFP fluorescence) and red (chlorophyll autofluorescence) channels. Bar = 10μM [Reproduced with permission from Annathurai Gnanasambandam, BSES Limited, Australia]

2.1.7.3 Protein targeting to mitochondria

Mitochondria are important organelles involved in ATP synthesis, photorespiration, and programmed cell death. The N-terminal mitochondrial presequence from F1-ATPase β-subunit (ATPase-β) of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia was shown to be effective in targeting GFP to the mitochondria (Petrasovits et al., 2007; Figure 4). Although this signal was used to target bacterial enzymes to sugarcane mitochondria, no PHB polymer accumulation was observed in transgenic sugarcane (Petrasovits et al., 2007).

2.1.7.4 Protein targeting to peroxisomes

Plant peroxisomes are involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, the glyoxylate cycle and photorespiration. The six amino acid C-terminal peroxisomal signal from Spinacia oleracea L. (spinach) glycolate oxidase was shown to be effective in targeting GFP to the peroxisomes in sugarcane leaves and callus (Gnanasambandam et al., 2008; Figure 4).

2.1.7.5 Protein targeting to ER

Almost all of the proteins that will be secreted to the cell exterior, as well as those destined for the lumen of the ER, Golgi apparatus, or vacuoles, are initially delivered to the ER lumen (Gal, 1998). The N-terminal ER signal peptide from Arabidopsis basic chitinase and a C-terminal HDEL signal for protein retention in the ER was efficient in targeting and retention of GFP in the ER in sugarcane leaves (Gnanasambandam et al., 2007; Figure 4). This HDEL signal in combination with the ER signal peptide of PinII was required for higher accumulation of GM-CSF in transgenic sugarcane (Wang et al., 2005a).

2.2 Target Traits and Products

For sugarcane genetic engineering, specific targets fall into two broad areas: (i) input traits that improve crop performance and productivity such as pest and disease resistance, tolerance to abiotic stress, herbicide tolerance, and alterations to plant architecture and (ii) output traits that modify quality and yield, compositions and use, such as production of more sucrose, biomass or novel compounds.

2.2.1 Disease resistance

Reports of pathogen-derived resistance to virus diseases include resistance to SCMV in otherwise susceptible sugarcane clones (Joyce et al., 1998; Ingelbrecht et al., 1999). Both groups used the coat protein gene of the virus driven by the Ubi-1 promoter with the nos terminator. Plants transformed with the coat protein gene of the SrMV strain SCH displayed a range of phenotypes, including immune, resistant, recovery, and susceptible plants, when challenged with virus. These observations enabled insights to the RNA-mediated PTGS resistance mechanism (Ingelbrecht et al., 1999). Virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) has been suggested as the mechanism of resistance against viral infections. Interestingly, transgenic plants having the same transgene integration pattern as determined by Southern blot analysis (i.e., clones) displayed a different response to mechanical SCMV infection. The reason for this peculiar result is still not clear (Ingelbrecht et al., 1999).

Sugarcane yellow leaf disease, which is characterized by yellowing of the leaf midribs followed by tissue necrosis, is caused by ScYLV (Borth et al., 1994; Schenck et al., 1997; Vega et al., 1997; Comstock et al., 1998). Economic losses from sugarcane yellow leaf disease of up to 50% have been reported (Vega et al., 1997). The ScYLV coat protein gene in the sense orientation driven by Ubi-1 was used to generate virus-resistant transgenic sugarcane. Resistance levels were evaluated with inoculation of viruliferous aphids. Virus titers were determined using tissue blotting and quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Two resistant transgenic sugarcane lines were identified based on the tissue blot analyses. However, virus RNA can still be detected using qRT-PCR in these lines. Greenhouse tests are currently being conducted to compare the yield difference between nontransformed and transgenic lines.

The transgenic approach for providing resistance to the more devastating viral disease in sugarcane, Fiji leaf gall has been tested (McQualter et al., 2004). Resistance to Fiji leaf gall was produced by microprojectile-mediated transformation with a transgene encoding a translatable version of Fiji disease virus (FDV) segment 9 ORF 1 under the control of the maize Ubi-1 promoter. The molecular phenotypes of the transgenic plants at both the DNA and RNA levels were not entirely consistent with a resistance mechanism based on PTGS. Transgenic plants showed very low steady state messenger-RNA (mRNA) levels under normal conditions, but many of these plants failed to show resistance upon challenge with the FDV virus, suggesting that the virus possessed a mechanism for overriding the post-transcriptional silencing mechanism. Further research required to achieve complete immunity to FDV includes: (i) additional characterization of the FDV genome, since only a superficial knowledge of the virus life cycle and replication strategy is currently known; (ii) a shotgun approach where all 12 ORFs contained within the FDV genome are used as transgenes, either singly or in various combinations (RNAi (RNA interference) silencing constructs should be employed in this case); and (iii) determining if FDV possesses a dsRNA (double-stranded RNA) binding protein with the ability to suppress gene silencing. If so, then a more effective approach to achieve pathogen derived resistance to FDV in sugarcane might require deactivation of this protein.

Leaf scald is a serious disease of sugarcane caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas albilineans. The bacterium produces a toxin (albicidin) that blocks plastid DNA replication of the sugarcane plant. Zhang et al. 1999 identified a bacterium that could survive in the presence of albicidin because it carried an albicidin detoxification gene (albD). This gene was cloned from the bacterium and introduced into sugarcane. Some of the resulting transgenic plants were resistant to leaf scald disease (Hansom et al., 1999). It is interesting to note that another bacterial pathogen of sugarcane Leifsonia xyli subsp. xyli (Lxx) like Xanthomonas albilineans colonizes the xylem vessels, was recently shown to have a gene homologous to the one in Xanthomonas albilineans encoding an enzyme to pump albicidin out of its cells (Monteiro-Vitorello et al., 2004).

2.2.2 Insect resistance

The potential for using a modified Bt gene encoding the δ-endotoxin CryIA(c) from Bacillus thuringiensis strain kurstaki to combat damage by the lesser corn-stalk borer (LCB) was demonstrated by Fitch et al. 1996. The Bt gene and the selectable marker gene nptII, were under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Bombarded sugarcane calli were selected stepwise on 50–200mgl–1 of G418, an aminoglycoside antibiotic similar in structure to gentamicin B1. Insect bioassays indicated that LCB larvae fed on some lines of calli or leaves from the regenerated plants weighed less and showed higher mortality than those fed on nontransgenic tissues. Mortality was higher when LCB were fed transgenic calli as opposed to transgenic leaves, possibly due to different levels of the CryIA(c) protein in the two different tissues, although the protein levels were not reported. Leaves from other putatively transformed lines had no detectable effect on larvae survival. Southern hybridization indicated that there were 1–5 copies of the Bt genes in the two most resistant lines.

Resistance to the other lepidopteran sugarcane stalk borers has also been reported using the δ-endotoxin gene from B. thuringiensis. Larval mortality and reduced levels of damage from Diatraea saccharalis in the field and Proceras venosatus in the glasshouse have been reported (Arencibia et al., 1997; Weng et al., 2006). In the short term, it is possible that intellectual property restrictions may limit widespread use of this technology in sugarcane. Consequently, the use of other antimetabolic compounds for improving plant resistance, such as proteinase inhibitors (Allsopp et al., 1996; Falco and Silva-Filho, 2003) and lectins (Sétamou et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2002c), has been tested with promising results from laboratory-based insect bioassays. These products impact on a wider range of insect/pests and studies on the effects on the Australian coleopteran whitegrub have been underway for several years (Allsopp et al., 1996).

Canegrubs are a major pest in the Australian sugar industry causing yield losses up to AU $80 million. The PinII and the snowdrop lectin (Gna) genes have both been used to generate transgenic sugarcane in attempts to control these pests (Allsopp et al., 1996; Nutt et al., 1999). Plants containing the pinII gene grew more slowly than the nontransformed control plants. This may have been due to metabolic disruption within the plants, as no pinII was found in the cell vacuole. Earlier work with artificial feeding trials had shown that avidin could reduce larval growth and increase larval mortality of Antitrogus parvulus (Childers canegrub) (Allsopp and McGhie, 1996). More recently, the gene for avidin, a biotin binding protein from chicken egg white, has been introduced into sugarcane for the control of canegrubs (Nutt et al., 2006). Transgenic sugarcane plants have been regenerated, which contain avidin concentrations of up to 0.06% of total protein.

2.2.3 Sucrose metabolism

A suite of physiological processes and enzymes involved in sucrose accumulation have been identified and characterized over the last 50 years. These processes include: leaf reactions, such as photosynthetic reactions, sucrose synthesis, metabolism and carbon partitioning across various membranes into different pools; phloem reactions, such as phloem loading in leaf, translocation to and unloading in various sink tissues (including primary storage in parenchyma cells of the stalk); stalk reactions, such as membrane transport, sucrose metabolism, carbon partitioning, and remobilization of stored sucrose; genetic and developmental controls, such as timing of maturation; and environmental perception and signal transduction pathways to coordinate plant development (Moore, 2005). Some of the genes encoding these enzymes have been cloned and used to transform sugarcane with the goal of altering sucrose accumulation (reviewed by Grof and Campbell, 2001). However, this reductionist approach has fallen short of expectation in almost all of the cases because of the complexity among the multitude of simultaneous processes and parallel pathways.

As tissue culture methods became established, they were exploited to elucidate the physiology and biochemistry of sugarcane carbohydrate accumulation, with particular emphasis on sugars (Komor et al., 1981; Thom and Komor, 1984). Transgenic sugarcane cell lines were also used to study the effect of invertase expression in different cellular compartments on sucrose accumulation (Ma et al., 2000). Overexpression of a yeast invertase gene (SUC2) in the apoplast led to rapid hydrolysis of sucrose and accumulation of hexoses, both in the medium and the cells, suggesting that hexose uptake, not hexose availability, was the limiting factor for sucrose accumulation. Cells transformed for overexpression of invertase in the cytoplasm did not show a significant change in the sugar composition in the medium, but did significantly reduce the sucrose content in the cells. Partial inhibition of the soluble invertase activity was achieved by transforming with a sugarcane soluble acid invertase complementary DNA (cDNA) (SCINVm) in the antisense orientation to result in increased sucrose accumulation. Intra- and extra-cellular sugar composition was very sensitive to changes in invertase activities in this tissue culture system (Ma et al., 2000).

Pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase (PFP) activity in sugarcane is inversely correlated to sucrose concentration in maturing internodal tissues, but no clear physiological role in sucrose metabolism has emerged (Whittaker and Botha, 1999). If endogenous PFP activity were to be down-regulated by antisense or co-suppression technologies, then sucrose concentration could be increased. In sugarcane transformed with the catalytic subunit, PFP-β, endogenous PFP gene expression was reduced by up to 40% and 80% in leaf roll and internodal tissue, respectively (Groenewald and Botha, 2001, 2008). Sucrose concentrations in these lines were significantly increased in immature internodes. This finding could make a valuable contribution to the productivity of sugarcane cultivars and elucidate the role of PFP in sucrose accumulation.

Vickers et al. 2005a attempted to modify the endogenous polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity in sugarcane by introducing sense and antisense constructs of the endogenous sugarcane PPO gene driven by the Ubi-1 promoter. The rationale behind this approach was that the inhibition of PPO activity in juice by chemical inhibitors, elevated pH or heat significantly reduced the color of the cane juice and the subsequent color intensity in sugar crystals. All transgenic lines, irrespective of the orientation of the PPO gene, showed higher PPO activity and more color units than the nontransformed commercial clones. Although higher levels of PPO activity were correlated to juice with a darker color, the converse was not true in this study. It has been hypothesized that a lowering of PPO activity will lead to a reduction in the color of juice and consequently raw sugar (Vickers et al., 2005a). As pale sugar has a market premium over dark sugar, this has potential economic benefits for the sugar industry.

While most transgenic attempts to improve sugar accumulation in sugarcane have met with limited success, a notable exception was the introduction of a bacterial gene encoding a sucrose isomerase (Wu and Birch, 2007) to produce a high-value sugar isomaltulose.

2.2.4 Alternative products