Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) 2025 consensus recommendations for the screening, diagnosis and classification of gestational diabetes

Abstract

Introduction

In the context of a global obesity and diabetes epidemic, gestational diabetes mellitus and other forms of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy are increasingly common. Hyperglycaemia in pregnancy is associated with short and long term complications for both the woman and her baby. These 2025 consensus recommendations from the Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) update the guidance for the screening, diagnosis and classification of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy based on available evidence and stakeholder consultation.

Main recommendations

- Overt diabetes in pregnancy (overt DIP) should be diagnosed at any time in pregnancy if one or more of the following criteria are met: (i) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/L; (ii) two-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) ≥ 11.1 mmol/L following a 75 g two-hour pregnancy oral glucose tolerance test (POGTT); and/or (iii) glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5% (≥ 48 mmol/mol).

- Irrespective of gestation, gestational diabetes mellitus should be diagnosed using one or more of the following criteria during a 75 g two-hour POGTT: (i) FPG ≥ 5.3–6.9 mmol/L; (ii) one-hour plasma glucose (1hPG) ≥ 10.6 mmol/L; (iii) 2hPG ≥ 9.0–11.0 mmol/L.

- Women with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy should be advised to have the HbA1c measured in the first trimester. Women with HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥ 48 mmol/mol) should be diagnosed and managed as having overt DIP.

- Before 20 weeks’ gestation, and ideally between ten and 14 weeks’ gestation, if tolerated, women with a previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus or early pregnancy HbA1c ≥ 6.0-6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol), but without diagnosed diabetes, should be advised to undergo a 75 g two-hour POGTT.

- All women (without diabetes already detected in the current pregnancy) should be advised to undergo a 75 g two-hour POGTT at 24–28 weeks’ gestation.

Changes in management as a result from this consensus statement

These updated recommendations raise the diagnostic glucose thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus and clarify approaches to early pregnancy screening for women with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy.

Gestational diabetes mellitus, defined as hyperglycaemia first detected at any time during pregnancy less than overt diabetes in pregnancy (overt DIP),1 is one of the most common disorders of pregnancy.2 Hyperglycaemia in pregnancy, including gestational diabetes mellitus, overt DIP and pre-existing diabetes (detected before pregnancy),1 increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (such as preeclampsia, higher infant birth weight and obstetric intervention) and neonatal complications (such as hypoglycaemia, respiratory distress and jaundice).2, 3 Women with gestational diabetes mellitus have increased risk of future type 2 diabetes, kidney disease and cardiovascular disease.4-7 In utero exposure to hyperglycaemia is also associated with long term cardiometabolic risks in the baby, including diabetes and obesity.8-10

The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) has historically developed and published clinical guidance in relation to diabetes in pregnancy in Australia.11-13 ADIPS last updated the guidelines for gestational diabetes mellitus testing and diagnosis in 2014,13 largely endorsing the 2010 International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups’ (IADPSG)14 and 2013 World Health Organization (WHO)1 recommendations. This followed the international Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study,3 and randomised controlled trial evidence of treatment benefit for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed from 24 weeks’ gestation.15, 16 HAPO showed a continuous positive association between increasing maternal glucose concentrations following the one-step 75 g two-hour pregnancy oral glucose tolerance test (POGTT) at 24–32 weeks’ gestation and perinatal complications at lower glucose thresholds than previous gestational diabetes mellitus diagnostic criteria. Based on these findings, several diagnostic glucose thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus were considered, corresponding to different thresholds of risk of primary complications in the HAPO cohort (odds ratio [OR], 1.5, 1.75 or 2.0 compared with risk at the mean glucose level for the overall cohort).14 The IADPSG made a consensus recommendation to adopt diagnostic glucose thresholds corresponding to a HAPO OR of 1.75 (fasting plasma glucose [FPG] 5.1–6.9 mmol/L, one-hour plasma glucose [1hPG] ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, and/or two-hour plasma glucose [2hPG] 8.5–11.0 mmol/L).14 Notably, some jurisdictions adopted higher diagnostic glucose thresholds (HAPO OR, 2.0; FPG 5.3–6.0 mmol/L; 1hPG ≥ 10.6 mmol/L; and/or 2hPG 9.0–11.0 mmol/L).17

In 2014, ADIPS recommended gestational diabetes mellitus be diagnosed any time during pregnancy based on HAPO OR 1.75 one-step POGTT glucose thresholds, as well as testing in early pregnancy in individuals with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy, ideally with a POGTT or a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test.13 The aim of these 2025 ADIPS consensus recommendations is to update our approach to the screening, diagnosis and classification of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy.

Methods

The ADIPS Board process to update our guidance was based on thorough evidence review and stakeholder consultation. Despite recent trials relevant to gestational diabetes mellitus screening and diagnosis, there remains no single best evidence-based approach. Substantial variation in practice exists locally and internationally. Given the continuum of risk between glycaemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes, there will always be arguments for and against any specific diagnostic thresholds. Therefore, we adopted a consensus-based approach to updating these evidence-based recommendations. The evidence reviews prepared for the 2024 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) diabetes in pregnancy guidelines18 and the draft New Zealand national clinical guideline on gestational diabetes mellitus19 were used with permission to inform development of these ADIPS recommendations.

Consultation included an IADPSG Summit on gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis in early pregnancy in November 2022,20 a workshop for ADIPS members in August 2023 regarding screening and diagnosing early gestational diabetes mellitus,21 and a conference hosted by ADIPS in May 2024 to update the screening and diagnostic approach for gestational diabetes mellitus early in pregnancy and at 24–28 weeks’ gestation.22 Delegates included multidisciplinary ADIPS members from across Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand and nominees of key stakeholders representing a range of health professional organisations, academics, policy makers, and consumers with lived experience.

Subsequently, this manuscript was drafted by the multidisciplinary ADIPS Board (elected from the membership to serve in a voluntary capacity) and circulated to key stakeholders and ADIPS members for feedback. Sixty written submissions were received from professional societies and colleges, consumer representatives, health services and networks, individual clinicians, and other stakeholders from across Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. These were reviewed and considered by the ADIPS Board, who adapted and finalised the Consensus Recommendations in a series of dedicated meetings. This manuscript has been reported according to the Accurate Consensus Reporting Document (ACCORD) (Supporting Information, table 1).23 The recommendations have been assessed against the Guidelines International Network checklist for modifying a disease definition (Supporting Information, table 2).24

Potential conflicts of interests were identified and managed throughout development of the recommendations. All authors completed a standardised declaration of interests form in early 2024, which included detailed information regarding potential financial, organisational, intellectual or other interests (summarised for public disclosure in the competing interests statement for this manuscript). Delegates at the May 2024 conference were asked to complete the same detailed form and, on the day, were required to fill in a one-page declaration form to be displayed on their table. Potential conflicts of interest were regularly and openly discussed at meetings of the authorship group. None of the authors have a direct pecuniary interest, and a minority have received unrelated financial support from industry, which is openly declared. Several authors are academic experts in the field and have relevant intellectual interests. Such interests were openly disclosed, and, when necessary, a member of the authorship group without a relevant interest moderated the discussion.

Recent evidence from high quality randomised trials

The Australian-led Treatment of Booking Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (TOBOGM) randomised controlled trial tested diagnosis and treatment for early gestational diabetes mellitus in 802 women with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy.25 Immediate treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus (75 g two-hour oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT] WHO 2013 criteria) diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation modestly reduced the risk of the perinatal composite outcome. No differences were observed in the other primary outcomes of pregnancy-related hypertension or neonatal lean body mass. Pre-specified subgroup analyses suggested an effect from immediate treatment among women with high glycaemic band (HAPO OR 2.0) OGTT diagnostic thresholds, but not in women diagnosed with the currently recommended low glycaemic band thresholds (HAPO OR 1.75). At 24–28 weeks’ gestation in the delayed treatment group, gestational diabetes mellitus was diagnosed and treated in 78% of women in the higher glycaemic band compared with 51% in the lower band. The remaining 33% of the women had discordant OGTTs, that is a negative OGTT at 24–28 weeks’ gestation despite their positive OGTT in early pregnancy (22% in the higher band and 49% in the lower band). In pre-specified subgroup analysis, benefit was observed in women who had the OGTT and were treated before 14 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.57–0.98), but not in women who had the OGTT at or after 14 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.64–1.09).25 Early treatment for gestational diabetes mellitus was cost-effective among high risk women in the higher glycaemic band when diagnosed before 14 weeks’ gestation.26

The New Zealand Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Study of Detection Thresholds (GEMS) randomised controlled trial evaluated the use of lower (IADPSG/WHO 2013) or higher (existing New Zealand FPG ≥ 5.5 mmol/L and/or 2hPG ≥ 9.0 mmol/L) glycaemic thresholds for the 75 g two-hour OGTT at 24–32 weeks’ gestation in 4061 women.27 In the overall population, the IADPSG criteria more than doubled the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus compared with the New Zealand guidelines (15.3% v 6.1%), with no difference in the primary outcome of large for gestational age offspring. Pre-specified secondary analysis compared outcomes between treated and untreated women who had OGTT results that fell between the lower and higher glycaemic criteria. In this subgroup, treatment for gestational diabetes mellitus was associated with reduced risk of large for gestational age babies (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.29–0.83) and pre-eclampsia (aRR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.002–0.60). However, treatment at these lower glycaemic thresholds was also associated with greater health service use and an increased risk of small for gestational age offspring,27 as well as lower lean mass and increased risk of early term birth,28 compared with women who were not treated. Six-month follow-up of the infants demonstrated no differences in fat mass between treated and untreated infants.28

Other relevant trials have not shown benefit from early testing and treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus, including among women with obesity in the United States29 and in Iran.30 These trials examined outcomes among all women undergoing screening. Gestational diabetes mellitus status, and thus treatment, differed between trial arms for only a small proportion of women.

Non-randomised trial evidence for fasting glucose as a diagnostic or screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus

Two quasi-experimental studies of real-world data in Australia examined two-step gestational diabetes mellitus screening using an initial FPG.31, 32 Only women with FPG 4.7–5.0 mmol/L were recommended a POGTT. FPG < 4.7 mmol/L at 24–28 weeks’ gestation was associated with low absolute risk of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy-related complications, including large for gestational age babies, respiratory distress, and neonatal higher acuity care admission.31, 32 A reanalysis of HAPO data demonstrated that women with FPG < 4.7 mmol/L had similar perinatal outcomes to women without gestational diabetes mellitus regardless of post-load values.33

Further analysis from HAPO showed that women with FPG ≤ 4.4 mmol/L but meeting the one-hour or two-hour glucose criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus, compared with women with FPG > 4.4 mmol/L who did not meet any IADPSG glucose thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus, had children with similar neonatal outcomes, childhood impaired glucose tolerance, and adiposity. However, women in the former group had higher rates of type 2 diabetes at ten to 14 years’ follow-up (aOR, 3.51; 95% CI, 1.41–8.75).34

Consumer experiences and stigma

Consumer experiences are essential when balancing outcomes and cost-effectiveness.35 A diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus may substantially affect women's psychological wellbeing.36-38 For some women, the diagnosis is a catalyst for positive behavioural change36 and improved quality of life.15 For others, the experience of both internalised stigma (guilt, shame, fear and anxiety) and externalised stigma (labelling, discrimination, depersonalising and judgment), coupled with burden of care that may include financial strain, increased surveillance, and dietary restriction, can lead to a reduced quality of life and negative pregnancy experiences that can persist post partum.39

Recommendations

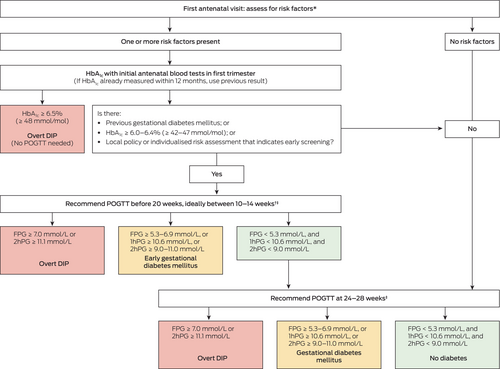

The updated screening and diagnostic recommendations are summarised in Box 1. As an underlying principle to these recommendations, ADIPS recognises the importance of person-centred, culturally safe and holistic care, where women are active participants in decision making. Evidence-based and culturally and linguistically appropriate materials about the rationale for gestational diabetes mellitus testing should be made available to all women and their families to support the implementation of these recommendations.

Box 1. Recommended approach to screening and diagnosis of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy

1hPG = one-hour plasma glucose; 2hPG = two-hour plasma glucose; BMI = body mass index; DIP = diabetes in pregnancy; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin; POGTT = pregnancy oral glucose tolerance test. * See Box 2. † POGTT (ie, 75 g two-hour oral glucose tolerance test) not recommended before ten weeks’ gestation but should be before 20 weeks’ gestation. ‡ See main text for options when POGTT is not tolerated or declined.

Diagnostic classification and criteria

Hyperglycaemia that is first detected at any time during pregnancy should be classified as either overt DIP or gestational diabetes mellitus. Early gestational diabetes mellitus refers to gestational diabetes mellitus detected before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Criteria for overt diabetes in pregnancy

- FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or 2hPG ≥ 11.1 mmol/L following a 75 g two-hour OGTT;

- HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥ 48 mmol/mol); and/or

- random plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L in the presence of clinical signs or symptoms indicative of hyperglycaemia.

Women with overt DIP should be managed similarly to those with pre-existing diabetes. At diagnosis, consideration should be given to the aetiology of diabetes, including the possibility of autoimmune diabetes. Not all women with overt DIP will have persistent diabetes post partum, but the risk of future type 2 diabetes is high.40, 41

Criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus at any gestation should be based on any one of the following values: (i) FPG ≥ 5.3–6.9 mmol/L; (ii) 1hPG ≥ 10.6 mmol/L; and/or (iii) 2hPG ≥ 9.0–11.0 mmol/L during a 75 g two-hour POGTT.

Recommendations for early testing for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy for women with risk factors

ADIPS recommends that women with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy (Box 2), who have not already been screened with a HbA1c measurement in the past 12 months, should have HbA1c measured at the first antenatal visit (generally in the primary care setting). The intent is to identify women with overt DIP. Services in areas with a high background population prevalence of type 2 diabetes may opt for universal HbA1c screening after consideration of logistic and cost implications.

Box 2. Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus, including odds ratios from published meta-analyses2, 42

| Risk factor | Odds ratio for gestational diabetes mellitus |

|---|---|

| Previous gestational diabetes mellitus | 8.4–21.1 |

| Obesity | 5.6 |

| Overweight | 2.8 |

| Family history of diabetes | 2.3–3.5 |

| Age | |

| 30–34 years | 2.7 |

| 35–39 years | 3.5 |

| ≥ 40 years | 4.9 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 2.0–2.9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.9 |

| History of adverse pregnancy outcomes | |

| Macrosomia | 2.5–4.4 |

| Pre-term delivery | 1.9–3.0 |

| Congenital anomaly | 3.2 |

| Stillbirth | 2.3–2.4 |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 3.2 |

| Multiparity | 1.4 |

- Women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.0–6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol) are recommended to undergo screening in early pregnancy. Women with HbA1c in this range have high rates of early gestational diabetes mellitus with a positive predictive value of 54% in a large study from Aotearoa New Zealand.43

HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥ 48 mmol/mol) is diagnostic of diabetes outside pregnancy and, in pregnancy, likely represents previously undiagnosed diabetes. Nevertheless, classification as overt DIP is appropriate until confirmatory post partum glucose assessment has been performed.

Early testing for gestational diabetes mellitus for women with risk factors

Women with a previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus or an early pregnancy HbA1c level ≥ 6.0-6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol), but without diagnosed diabetes, should be advised to undergo a 75 g two-hour POGTT before 20 weeks’ gestation, ideally between ten and 14 weeks’ gestation but considering factors such as nausea. POGTT should not be performed before ten weeks’ gestation due to poor tolerance and limited evidence of benefit.

Key risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy include previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus and HbA1c ≥ 6.0-6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol).3, 18 Women with HbA1c ≥ 6.0-6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol) in early pregnancy may have pre-existing intermediate hyperglycaemia and are at high risk of developing future type 2 diabetes.18, 40 Observational studies demonstrate that intermediate hyperglycaemia (HbA1c ≥ 6.0-6.4% [≥ 42–47 mmol/mol]) is associated with elevated risk of pregnancy complications.43-46 These thresholds are consistent with the accepted Australian definition of pre-diabetes outside of pregnancy.47

In addition to women with previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus or HbA1c ≥ 6.0–6.4% (≥ 42–47 mmol/mol), clinicians may offer screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (with a 75 g two-hour POGTT) in early pregnancy to women with other risk factors (Box 2) based on individualised risk assessment, the woman's preferences after informed discussion, or local policies.

Universal testing for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy at 24–28 weeks’ gestation

All women (without diabetes already detected in the current pregnancy) should be advised to undergo a 75 g two-hour POGTT at 24–28 weeks’ gestation (ie, universal testing).

Suggested approaches when oral glucose tolerance test is not undertaken

Some women are unable to tolerate the POGTT (eg, women who have had bariatric surgery) and/or will choose not to have a POGTT. When a POGTT is not undertaken, we suggest that women undergo FPG measurement. However, women should be counselled that identification and treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus defined by elevated glucose concentrations following a glucose load is supported by high quality evidence,15, 16 and that gestational diabetes mellitus cannot be excluded without a POGTT.

Women with FPG ≥ 5.3 mmol/L in either early pregnancy or at 24–28 weeks’ should be diagnosed and managed as having gestational diabetes mellitus. In early pregnancy, women with FPG < 5.3 mmol/L can await further screening at 24–28 weeks’ gestation. There is limited evidence for alternatives to POGTT in early pregnancy. At 24–28 weeks’ gestation, women with FPG 4.7–5.2 mmol/L should be recommended to undertake further testing with a POGTT where tolerated. Some clinicians might suggest a period of capillary self-blood glucose monitoring or continuous glucose monitoring. In Australia, government subsidies for glucose monitoring supplies are restricted to people with a diabetes diagnosis. There is currently no established evidence to guide the duration of monitoring, glucose thresholds or metrics required for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis via self-blood glucose monitoring or continuous glucose monitoring. We anticipate that emerging evidence will inform the appropriate use of continuous glucose monitoring in this context.

In later pregnancy, HbA1c is not recommended for gestational diabetes mellitus screening due to poor sensitivity, arising from the physiological fall of HbA1c by the second trimester, leading to the underestimation of HbA1c.48 Women with early pregnancy HbA1c ≥ 6.0–6.4% (≥ 42-47mmol/mol) who have not completed a POGTT should be offered the option of commencing glucose monitoring and dietary education (as per a diagnosis of early gestational diabetes mellitus).18 Although HbA1c at these thresholds is highly specific for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed on POGTT, the positive predictive value is limited in many populations.48

Other considerations

Impact on care delivery for gestational diabetes mellitus

Although gestational diabetes mellitus detection allows implementation of appropriate management to reduce risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, a gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis can also be associated with adverse experiences for some women, often related to how care is delivered. Even though the management of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy is beyond scope of this guidance, it is suggested that local policies take a holistic, individualised approach to risk stratification when considering inclusion or exclusion of women from the range of maternity models of care. The development of pathways for safe de-escalation of gestational diabetes mellitus monitoring and management should be considered when self-blood glucose monitoring levels are consistently normal.

Test accuracy and accessibility

Clinicians should be aware of the limitations of plasma glucose measurement. Pre-analytical factors (choice of blood collection tube, delayed transport, delayed separation of plasma from cells) can lead to marked underdiagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus due to in vitro glycolysis before sample processing.49, 50 Standardised approaches to pre-analytical sample handling are needed51 and a consensus-based Australian guidance is in preparation. The recommended approach to screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus relies on a single OGTT, which has limited reproducibility.49 This approach is based on available trial evidence,15, 16 known associations between all POGTT glucose measures and adverse outcomes,2, 3 and concerns associated with a glucose challenge two-step process, such as limited sensitivity of the initial screening test and risk of missed or delayed diagnostic testing.52-54

Accessibility and acceptability of testing are important considerations. Inclusion of HbA1c screening in early pregnancy will help ensure women with overt DIP and highest risk of adverse outcomes are afforded appropriate care. Evidence from Aotearoa New Zealand suggests that routine HbA1c measurement reduces disparities in screening.55 Significant barriers to POGTT screening have been reported in remote First Nations communities in Australia,56 where improving pregnancy outcomes relating to diabetes is an identified priority.57 Despite the greater pre-analytical stability of HbA1c compared with glucose, clinicians should be aware of factors that may alter the reliability of HbA1c as a marker of glycaemia (eg, increased or reduced red cell turnover) or interfere with some assays.58 In such circumstances, early POGTT should be considered for women with risk factors.

Evidence for previous lower glucose thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis

Dichotomising the risk continuum between maternal glucose and adverse pregnancy outcomes for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis has inherent limitations. The TOBOGM subgroup analysis supports higher glycaemic thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis in early pregnancy,25 and having consistent criteria across pregnancy was a key priority for stakeholders.20-22 However, raising the POGTT diagnostic thresholds at 24–28 weeks’ gestation means that women (and their offspring) at risk of adverse perinatal and long term cardiometabolic outcomes previously diagnosed at HAPO OR 1.75 thresholds3, 8, 10 will no longer be identified as having gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes screening and prevention strategies may be considered for these women into the future after pregnancy, especially those meeting non-pregnancy criteria for intermediate hyperglycaemia (2hPG ≥ 7.8 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥ 6.0% [≥ 42 mmol/mol]).18 GEMS suggested that women diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus via the lower POGTT thresholds had some maternal and infant health benefits compared with women with the same mild degree of hyperglycaemia who were not diagnosed with (or treated for) gestational diabetes mellitus.27 The newly recommended higher thresholds will still identify more women as having gestational diabetes mellitus than the previous New Zealand criteria used in the GEMS control group due to a lower FPG cut-off and the addition of a one-hour POGTT glucose threshold. Where there is concern, transition from the use of the former 2014 ADIPS lower gestational diabetes mellitus diagnostic criteria13 may warrant the development of local implementation strategies.

Future research directions

Opportunities remain to improve hyperglycaemia in pregnancy detection and diagnosis. Additional trials with long term follow-up are needed to confirm the benefits of treating early gestational diabetes mellitus and to determine the most appropriate diagnostic thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus.

These new screening and diagnosis recommendations should be subjected to evaluation in pre–post implementation studies involving diverse populations and settings. Further research should explore simplifying screening methods, including examining the utility of the 75 g one-hour POGTT (ie, fasting and one-hour glucose only) for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus, assessing lower thresholds of early pregnancy HbA1c that might minimise the need for confirmatory POGTT,59 and re-evaluating the need for universal POGTT testing at 24–28 weeks’ gestation.

Further research is needed into identifying a more acceptable and reproducible test than the 75 g two-hour POGTT. Precision medicine and continuous glucose monitoring have potential future roles in risk stratification and early prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus.60, 61 Ultimately, future research should consider the holistic assessment of metabolic health beyond glycaemia and ensure that evidence-based management strategies are available to all women with increased risk of adverse outcomes during and after pregnancy.

Inclusivity statement

ADIPS recognises the great diversity within the pregnancy population, including but not limited to ethnicity, First Nations status, migrant and refugee status, sociocultural background, and gender identity. The terms “woman” and “women” are used as general and unifying terms. ADIPS affirms inclusive and respectful maternity care, with use of terms that are preferred by individuals.

Organisational endorsements

At the time of publication, the 2025 ADIPS consensus recommendations have been endorsed by the Australasian Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine (AACB), the Australian College of Midwives (ACM), the Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA), the Australian Diabetes Society (ADS), Diabetes Australia, the Endocrine Society of Australia (ESA), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia (RCPA), and the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ). The ADIPS 2025 consensus recommendations for the screening, diagnosis and classification of gestational diabetes have been officially recognised as an Accepted Clinical Resource by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP).

Acknowledgements

The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) acknowledges the many ADIPS members, representatives of key stakeholder organisations, and other interested clinicians, consumers and policy makers who contributed to and provided feedback on these consensus recommendations. ADIPS received no specific funding for this work. ADIPS gratefully acknowledges support from NSW Health and the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE) towards the 2024 ADIPS GDM Screening and Diagnosis Conference. Arianne Sweeting received support from the Australian Diabetes Society (ADS) Skip Martin Fellowship and a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1148952). Matthew Hare received support from the ADS Skip Martin Fellowship and an NHMRC Investigator Grant (1194698). Susan de Jersey received support from a Metro North Health Clinician Research Fellowship.

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by Charles Darwin University, as part of the Wiley - Charles Darwin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Competing interests

Matthew Hare has received honoraria for lectures and consultancies from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Rosemary Hall has received speaking honoraria from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Dexcom, and served on the New Zealand Diabetes Advisory Boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Abbott and Novo Nordisk. David Simmons has received honoraria for lectures and consultancies from Novo Nordisk, Ascensia, Abbott and Sanofi, educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Asensia, and equipment from Roche. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society has received industry sponsorship for conferences and research grants.

Provenance

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, project administration, and writing (review and editing). Arianne Sweeting, Matthew Hare, Susan de Jersey and Alexis Shub contributed to writing (original draft).