Rising prevalence of celiac disease is not universal and repeated testing is needed for population screening

Abstract

Background

Recent studies suggest that the prevalence of celiac disease is rising. We previously established the prevalence of celiac disease in healthy blood donors in 2002.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine whether the prevalence of celiac disease and celiac disease autoimmunity has changed over time by performing a similar prospective study.

Methods

Healthy blood donors (n = 1908) were tested for tissue transglutaminase antibodies and for anti-endomysial antibodies when positive. Further evaluation followed accepted criteria for diagnosis.

Results

Overall, 32 donors had abnormal tissue transglutaminase antibodies (1.68%). Eight donors had tissue transglutaminase antibodies >3 × upper limit of normal (0.42%), two of them with tissue transglutaminase antibodies >10 × upper limit of normal, while 24 donors had tissue transglutaminase antibodies <3 × upper limit of normal (1.26%). Most of the donors with positive tissue transglutaminase antibodies <3 × upper limit of normal had negative tissue transglutaminase antibodies levels on repeated testing (18/19). Celiac disease was diagnosed in four donors with positive tissue transglutaminase antibodies, establishing a prevalence of 1.68% (95% confidence interval 1.15–2.3) for celiac disease autoimmunity and 0.21% for celiac disease (95% confidence interval 0.07–0.5%).

Conclusion

The prevalence of celiac disease in blood donors in Israel did not rise in the last 15 years, suggesting that the increased prevalence of diagnosed celiac disease is mainly due to increased awareness. As most of the donors with elevated tissue transglutaminase antibodies <3 × upper limit of normal were endomysial antibody negative and had a negative tissue transglutaminase antibodies result upon re-testing, repeated tissue transglutaminase antibodies testing is required when screening asymptomatic populations for celiac disease.

Key summary

- What is the established knowledge?

- Studies suggest that the prevalence of celiac disease (CD) is rising.

- It is debated whether there is a true increase in prevalence or merely increased awareness.

- What is new in this study?

- The prevalence of CD in blood donors in Israel did not rise in the last 15 years.

- Repeated serology testing is required when screening populations.

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disease that arises in genetically susceptible individuals while exposed to gluten. CD predominantly affects the small intestine but is associated with numerous complications including an increased risk for certain malignancies, osteopenia, and other autoimmune diseases.1

Early diagnosis of CD and adherence to a gluten-free diet can reduce the complications of CD.2,3 Since the ratio between diagnosed and undiagnosed cases is estimated to be 1:3 to 1:54-6 screening populations may identify a large proportion of undiagnosed cases. Indeed, prevalence studies documented a much higher percentage of CD autoimmunity and CD than the reported prevalence of diagnosed CD.5,7-10

Worldwide, the prevalence of CD autoimmunity (positive serology) ranges between 0.2–8.5%, while the prevalence of CD that was verified by intestinal biopsies is 0.2–2.4%.11 When evaluating the incidence or prevalence trends of CD, it was shown that the incidence of biopsy proven CD in the Netherlands increased almost threefold between the years 1995–2010.12 West et al. found a fourfold increase in the incidence of CD in the UK over 22 years.13 Prevalence studies suggest a true rise in the prevalence of CD.14,15 Even when using the same serologic screening tests, studies in Italy have shown increasing prevalence of CD.16 In a systematic review of prevalence studies, Kang et al., concluded that the frequency of CD is increasing worldwide with significant geographical differences.17 It is still debated, whether the increased prevalence is genuine or is it merely due to increased awareness by healthcare providers.

In Israel, a study by Dahan et al. in 1984 based on diagnosed cases, estimated the prevalence of CD to be 1.7 per 1000 live births, with an almost continuous rise in incidence from 1970 to 1978.18 Israeli et al., performed serologic screening of adult Jewish recruits at 2003. The prevalence of overt CD prior to recruitment was 0.12%, while the overall prevalence – based on positive serology – was 1.1%, and biopsy-proven CD was diagnosed in 0.7%.19 In a recent publication, we searched the medical records in the enlistment database of above 2 m Jewish adolescents in Israel from 1988–2015 and observed an increase in the prevalence of diagnosed CD from 0.5% to 1.1% from 1998–2015.20 In our own previous study of healthy blood donors, published in 2001, we found an undiagnosed CD prevalence of 0.6% (confidence interval (CI) 95%).21

Since the above-mentioned recent national population study of young adolescents has demonstrated a more than twofold increase in the prevalence of diagnosed CD in Israel,20 our aim was to explore whether the prevalence of CD and CD autoimmunity has similarly increased in healthy blood donors. Since the prevalence of CD autoimmunity and CD in healthy blood donors is less likely to be affected by awareness of healthcare providers or families, we expected to observe an increase in the prevalence of CD autoimmunity and CD compared to the prevalence observed in the similar screening of healthy blood donors that we performed 15 years earlier.

Materials and methods

A total of 1908 serum samples were collected from volunteer healthy blood donors between the years 2013–2016. We recruited consecutive blood donors based on availability of registered co-investigators (assigned blood donor workers). All participants filled a questionnaire including details on age, sex, known illnesses, gastro-intestinal (GI) complaints, anemia, oral ulcers, osteoporosis, and history of CD or other illnesses in family members when donating blood. All samples were screened for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution's Human Research Committee (Tel Hashomer Medical Center: approval number 9541, October 2012; Rabin Medical Center: approval number 0029-14-RMC March 2014). All participating blood donors signed an informed consent. Samples were stored at −20°C until testing. All samples were tested for human recombinant tissue transglutaminase (TTG) antibodies. Anti-TTG immunoglobulin (Ig)A antibodies were determined using a commercial Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) assay (Eurospital, Trieste, Italy), based on recombinant human TTG as an antigen. The test was quantitative, and values were obtained in units/ml (U/ml). Results ≥ 16 U/ml were considered positive. Results between 9–16 U/ml were considered borderline. Results < 9 U/ml were considered negative.

All samples > 9 U/ml (borderline and positive) were defined as CD autoimmunity and were then tested for anti-endomysial antibodies (anti-EMAs). IgA EMA was tested by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using primate smooth muscle as substrate (IMMCO Diagnostics, Buffalo, New York, USA) with a cut-off of 1:5. Positive sera were diluted to the highest dilution yielding fluorescence.

Participants with positive TTG antibodies were approached by one principal investigator (RL-C). They received an explanation about the serological markers found, the possibility of CD, its significance, and the role of intestinal biopsy in the diagnosis of CD. Participants with anti-TTG antibodies> × 3 upper limit of normal (ULN) were advised to have intestinal biopsies taken. Participants reluctant to undergo biopsy were asked to repeat serology, either in our hospital, or through their family physician. All participants with anti-TTG antibodies<3 × ULN were asked to repeat serology. A detailed report with the serologic studies was sent to each participant. Participants repeated serology by 12 months after the first serology.

Intestinal biopsies were done in the Tel Hashomer hospital during upper endoscopy. Multiple biopsies were taken from the second/third part of the duodenum. All biopsies were checked by a single pathologist (MS) who was blinded to the serology findings. Pathological diagnosis of CD was defined as Marsh 3 lesion on intestinal biopsies.22 Patients were defined to have CD based on European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) criteria.23

Statistics

Nominal data was analyzed by Chi-square test, scale data was analyzed by t-test.

Results

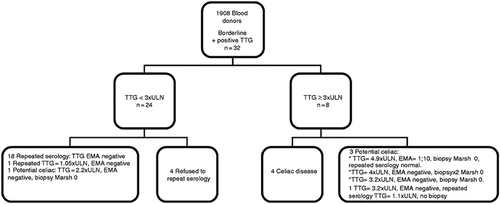

Overall, 1908 blood donors participated in the study including 669 women (35%). Mean age was 36.7 years, median age 36, range 18–69 years. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the study.

Flow chart of the study.

EMA: endomysial antibody; TTG: tissue transglutaminase; ULN: upper limit of normal.

Intestinal complaints were reported in 385 patients (20%). These included abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite. The characteristics of the whole study population versus healthy blood donors with positive anti-TTG antibodies is provided in Table 1. Age, sex, and GI complaints were similar in both groups. None of the participants reported having CD.

| Characteristics | Blood donors (n = 1908) | Positive serology (n = 32) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 36.7 ± 12.1 | 36.1 ± 12.06 | 0.781 |

| Male sex (%) | 1236 (64.8%) | 20 (62.5%) | 0.785 |

| GI complaints | 385 (20.2%) | 7 (21.8%) | 0.809 |

| Abdominal pain | 253 (13.2%) | 4 (12.5%) | 0.898 |

| Diarrhea | 254 (13.3%) | 5 (15.6%) | 0.698 |

| Constipation | 100 (5.2%) | 1 (3.1%) | 0.588 |

| Nausea | 24 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Vomiting | 24 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Loss of appetite | 23 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.53 |

| Weight loss | 21 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.54 |

- GI: gastro-intestinal; SD: standard deviation.

Out of 1908 blood samples, 32 participants (1.68%) had CD autoimmunity with anti-TTG antibodies above 9 U/ml. Of these, 24 had anti-TTG antibodies<3 × ULN (1.26%), and eight had anti-TTG antibodies>3 × ULN (0.42%). Anti-EMA was positive in six donors (0.31%), five of them with anti-TTG antibodies>3 × ULN, and one with anti-TTG antibodies = 2 × ULN. All donors with anti-TTG antibodies>3 × ULN (n = 8) were referred for intestinal biopsy. The characteristics of the donors with positive anti-TTG antibodies who underwent small bowel biopsies are provided in Table 2. Overall, four participants were diagnosed with CD (0.21%). Three donors were diagnosed with CD by intestinal biopsy. One donor (male, 50 years old, no GI complaints or comorbidities), refused biopsy and probably has CD since he has anti-TTG antibodies>100 U/ml (upper limit of the serology kit, above 11 × ULN), anti-EMAs 1:40 and positive family history of CD. One donor with anti-TTG antibodies = 3.2 × ULN anti-EMA negative refused biopsy and repeated serology was anti-TTG antibodies = 1.1 × ULN, and is therefore considered as part of CD autoimmunity only.

| No. | Age | Sex | Gastrointestinal complaints | Family history of CD | Comorbidities | Anti-TTG (U/ml) | EMA (titer) | Intestinal biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | Female | No | No | Hypothyroidism | 72 | 1:20 | Marsh3B |

| 2 | 31 | Female | No | No | No | 47 | 1:5 | Marsh 3B |

| 3 | 18 | Male | Abdominal pain | No | No | >100 | 1:40 | Marsh 3C |

| 4 | 40 | Male | No | No | No | 44 Seven months later: 7 | 1:10 Negative | Marsh 0 |

| 5 | 44 | Male | No | No | No | 36 A year later: 38 | Negative Negative | Marsh 0 Marsh 0 |

| 6 | 25 | Male | No | No | Psoriasis | 29 | Negative | Marsh 0 |

| 7 | 41 | Male | No | No | No | 20 | Negative | Marsh 0 |

- CD: celiac disease; EMA: endomysial antibody; TTG: tissue transglutaminase; ULN: upper limit of normal.

In the group with anti-TTG antibodies <3 × ULN (n = 24), 19 repeated serology and four refused. Eighteen donors had negative serology. One donor had a repeated low borderline serology (anti-TTG antibodies = 1.05 × ULN) and was lost to further follow-up. One donor with anti-TTG antibodies = 2.2 × ULN and anti-EMA negative elected to perform an intestinal biopsy and did not have CD (Marsh 0).

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that the prevalence of CD autoimmunity and CD has not significantly changed in a national cohort of healthy blood donors over the last 15 years. Furthermore, when screening populations, follow-up serology tests are required for CD diagnosis as low titers may normalize over time.

In our previous study in blood donors, 15 years ago,21 the prevalence of CD autoimmunity and of CD was 3.8% (95% CI 2.9–4.8%) and 0.6% (95% CI 0.3–1.1%), respectively. In our current study and employing a similar methodology, we found CD autoimmunity and CD in 1.68% (95% CI 1.15–2.3) and 0.21% (95% CI 0.07–0.5%) respectively. Moreover, even if assuming that the four participants in our study who had refused to repeat serology testing are indeed inflicted by CD, we would still have a prevalence of 0.42% (95% CI 3.3–5.1) at most. Thus, given the overlap of the confidence intervals between the current and the previous cohorts, there does not seem to be an increase in the prevalence of CD in healthy blood donors, though we cannot rule out an actual decrease in prevalence of CD in healthy blood donors.

Our findings are in agreement with the findings of Virta et al., who recently examined a population-based registry in Finland.24 They observed a decline in the incidence of biopsy proven CD from 2005–2014 in middle and old aged people, and especially in women. Burger et al. did report an increase in biopsy proven CD in the Netherlands, however a trend toward leveling of incidence was observed from 2008–2010.12 Also, Kivelä et al. reported in 2015 that in a large cohort of Finish children, CD autoimmunity increased in early 2000s but since then fluctuated without a trend.25

Our results differ from previous studies which show an increase in the prevalence and incidence of CD over the years, 17,26-28 including the recent publication of Grode et al. who reported that the prevalence of diagnosed CD in Denmark has doubled each decade from 1986–2016.29

In Israel, we recently showed that there was an increase in the prevalence of diagnosed CD from 0.5% to 1.1% over the last 20 years in young Jewish adolescents.20 However, the current study shows that there was no increase in the prevalence of CD in healthy blood donors over the last 15 years. The differences in our results may be attributed first and foremost to increased awareness of healthcare providers with increased testing and increased diagnoses that would increase the prevalence in a population study based on confirmed cases, but not when screening healthy blood donors. However, the population-based study examined the prevalence in young adolescents, 20 years younger in average than the present cohort. Arguably therefore, this seeming discrepancy may represent a genuine increase in prevalence, which will manifest within the next decades also by an increased rate among the healthy blood donors' cohort.

Different factors influence the prevalence of CD and CD autoimmunity. Catassi et al. suggested that the major factors responsible for the variation in prevalence of CD is the prevalence of Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-related predisposing genotypes DQ2 and DQ8, and the average consumption of wheat and other gluten containing cereals.16 Yuan et al. observed a 12-times higher prevalence of CD autoimmunity in Northern regions of China where wheat is the staple diet compared to areas where rice is the staple diet.30 It has also been suggested that currently used industrial gluten is more toxic and is responsible for the increased prevalence of CD.31 Finally, it is plausible that as GI infections increase the susceptibility to CD, increased hygiene and less GI infections may cause a decrease in the prevalence of CD in certain regions.32,33

Although our primary aim was to find whether there is a change in the prevalence of CD, we also followed up on the donors with CD autoimmunity. Our major observation was that most of the donors with anti-TTG antibody levels < 3 × ULN that repeated serology, had negative serology on follow up. In concordance with our finding, Cilleruelo et al. studied the natural history of CD autoimmunity in a cohort of at risk children (HLA DQ2 positive). In that study, 42% of children with potential CD or CD autoimmunity became serology negative and were still serology negative 5–7 years afterwards.34 Liu et al. prospectively followed children with genetic risk factors for CD. Seropositivity for anti-TTG antibodies resolved spontaneously in 46% of subjects with CD autoimmunity.35 Furthermore, in our study, all donors with positive anti-TTG antibodies>3 × ULN and negative anti-EMAs had either a normal intestinal biopsy (potential CD) or low borderline anti-TTG antibodies on follow-up. These results are in line with studies showing that anti-TTG antibodies may normalize over time in asymptomatic subjects with a normal biopsy,36 but also with the fluctuating nature of CD autoimmunity as demonstrated by Volta et al., who followed up a group of adults with potential CD, in which antibody markers disappeared or fluctuated in 5/16 asymptomatic patients (31.5%), and only one developed CD.37 Imperatore et al. showed that over a six-year period, 69% of asymptomatic potential CD developed CD-related symptoms.38 In our study, all anti-EMA positive donors but one, were diagnosed with CD (from which one patient refused biopsy but is most probably CD). Our findings reiterate the importance of follow-up serology and of confirmatory anti-EMA testing in establishing the true prevalence of CD autoimmunity and of CD when studying populations.

There are certain limitations to our study. First, we cannot ascertain that the demography of blood donors did not change over the years and more people who are diagnosed with CD or may have undiagnosed CD refrain from donating blood. Second, we used different serology kits, and in contrary to our previous study, we did not examine IgA levels, since in our previous study we had no IgA deficient donors diagnosed with CD. Third, as bulb biopsies were not taken and even multiple duodenal biopsies can miss patchy disease, we cannot rule out the possibility that duodenal biopsies missed existing CD lesions. Fourth, we cannot rule out that some of the donors with fluctuating anti-TTG antibodies were on a gluten-free diet without declaring it, although it is unlikely since donors reported gluten-containing diet on all follow-up telephone calls. Lastly, we lack long-term follow-up to assess the donors with potential CD, and whether anti-TTG antibodies levels rise again in the donors in which it declined spontaneously. Nevertheless, the strength of our study is the study design that used the same methodology of screening healthy blood donors enabling an objective assessment of the change in prevalence 15 years following the previous study.

In conclusion, the prevalence of CD in healthy blood donors in Israel did not rise in the last 15 years, suggesting that the reported rising prevalence of CD is not universal. These findings may serve as a basis to explore genetic and environmental factors responsible for differences in prevalence between countries and changes over time. Finally, these observations indicate that when screening populations, repeated serology testing is pertinent in order to establish the true prevalence of CD autoimmunity and CD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their acknowledgment to the Magen David Adom phlebotomist team. All authors approved the final version of this article. The abstract was presented as a poster at the 51st European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Nutrition annual meeting in Geneva, Switzerland from 9–12 May 2018. The conference organizers were not granted a license for the work.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None of the authors declared any conflict of interest regarding this study.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review boards where blood donors were recruited.

Funding

Kits for ELISA assay for TTG antibodies were provided by Eurospital, Trieste, Italy. Eurospital involvement in the study was strictly limited to the provision of the kits.

Informed consent

Each blood donor provided signed informed consent prior to recruitment.