Stigma in Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: Consequences and the Moderating Role of IntentionalSelf-Regulation

Abstract

Aims: To verify the association of stigma with mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and to examine whether intentional self-regulation buffers the negative consequences of stigma.

Methods: This study used a cross-sectional design with a convenience sample. A total of 307 adolescents with T1D were recruited from February 2022 to August 2023. Diabetes-specific stigma, intentional self-regulation, mental well-being, and self-management competency were assessed using self-reports measurement tools. Glycated hemoglobin levels evaluated glycemic control. We used simple slopes and Johnson–Neyman (J–N) analyses to probe significant interactions.

Results: Stigma was negatively associated with mental well-being and self-management competency among adolescents with T1D. The association between stigma and glycemic control was only found in the preadolescence group (≤13 years). Intentional self-regulation moderated the association of stigma with mental well-being and self-management competency. In short, the negative effect of stigma on mental well-being and self-management competency became nonsignificant in the context of high intentional self-regulation.

Conclusions: Stigma is associated with impaired mental well-being and decreased self-management competency among adolescents with T1D. This study highlights intentional self-regulation as a potential mechanism linking stigma to negative psychological and behavioral outcomes and guides developing stigma-reduction interventions.

Summary

- •

Stigma was negatively associated with mental well-being and self-management competency among adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D). The association between stigma and glycemic control was only found in the preadolescence group (≤13 years).

- •

The negative association of stigma with mental well-being and self-management competency became nonsignificant in the context of high intentional self-regulation.

- •

Healthcare providers should use judgment-free and non-biased language when communicating with adolescents with T1D and provide supportive training programs to enhance adolescents’ intentional self-regulation.

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is one of the most common incurable pediatric medical illnesses and over 149,500 children and adolescents worldwide are diagnosed with T1D each year [1]. This concealable illness usually begins at a young age and is characterized by unpredictable hypoglycemic symptoms [2]. Moreover, the noticeable self-management tasks, including insulin injection and blood glucose testing, make people with T1D different from their peers and may be misunderstood as drug users [3]. These disease characteristics make people with T1D susceptible to stigma. Stigma involves labeling persons with negative attributes and stereotypes that lead to discrimination [4]. In our study, stigma is defined as individuals’ perception of others as having negative attitudes toward them or the direct experience of social discrimination due to T1D [5]. Adolescents reported higher levels of stigma when compared to middle-aged and older adults [6]. In a mixed population of adolescents and young people with T1D, 63.5% reported having experienced stigma [7]. An international consensus published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology urges research on the psychological, behavioral, and physical consequences of diabetes stigma across all life stages [8].

In a descriptive study involving youth and adults with T1D, perceived stigma was positively associated with diabetes distress and depression [6]. Only one study has examined stigma to mental well-being among adolescents with T1D [7], focusing on internalized stigma while neglecting perceived and experienced stigma. Moreover, limited studies have examined stigma and self-management associations in T1D, yielding inconsistent conclusions [9]. Existing studies utilize three indicators of diabetes self-management, including self-care activities, appraisal of insulin treatment, and management self-efficacy. Much research on T1D has shown that adolescents’ self-management competency is an essential predictor of actual diabetes management [10, 11]. In a sample of people living with epilepsy, individuals with high stigma report lower self-management competency [12]. However, no studies have explored the relationship between stigma and self-management competency in adolescents with T1D. Regarding glycemic control, only three studies have reported a negative association between stigma and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in adolescents with T1D [7, 13, 14]. All three studies were conducted in Western countries. Perceptions and experiences about the stigma can vary widely across societies and cultures [15]. Specific studies on adolescents from other ethnic backgrounds are needed to evaluate the negative health consequences of T1D stigma. Moreover, examining the potential moderators that may lessen the deleterious effects of T1D stigma on mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control is vital.

Research has shown that the capacity to self-regulate is one potential critical dimension that may control or alter responses to stigma [16]. Intentional self-regulation, an influential personal asset adolescents use to engage in positive behaviors over time, consistently promotes healthy and positive development across the lifespan [17]. Empirical research has focused on the direct relation between intentional self-regulation and mental health. For example, in a study conducted in socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents, authors found that participants with higher intentional self-regulation also had fewer depressive symptoms [18]. Similarly, Zhou et al. [19] reported that intentional self-regulation significantly predicted mental well-being among nursing students. Although no evidence exists in adolescents with T1D, research has found that higher intentional self-regulation was associated with more activity involvement and health behaviors in other populations [20, 21]. In addition to its direct effects, intentional self-regulation would have a health promotion effect by buffering the negative consequences of stigma. Theories of intentional self-regulation emphasize that adolescents with good intentional self-regulation are more inclined to evaluate their abilities, negotiate resources within environments, and sharpen goal-directed behaviors when confronted with a stressful event such as experiencing stigma, in turn reducing problem behaviors and attaining better functioning [22, 23]. However, the interaction effect of stigma and intentional self-regulation in adolescents with T1D has never been examined. Identifying factors that may lessen the influence of stigma on mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control is essential to guide future interventions aimed at improving health outcomes in these vulnerable adolescents.

This study expands on the existing literature by (1) investigating the association of stigma with mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control in adolescents with T1D and (2) examining the moderating effect of intentional self-regulation between stigma and relevant outcome variables. We hypothesized that adolescents with adequate intentional self-regulation skills would demonstrate better mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control than adolescents who lacked intentional self-regulation in the context of severe stigma.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This study adopted a cross-sectional design. Adolescents with T1D were consecutively recruited from two academic hospitals between February 2022 and August 2023 in China. World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescence as between 10 and 19 years old [24]. Therefore, we included adolescents aged 10–19 years. Other inclusion criteria included being diagnosed with T1D for at least 6 months, receiving intensive insulin treatment, and being able to read or understand the Chinese language. We excluded participants with major psychiatric (e.g., schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorder) or neurocognitive disorders (e.g., delirium and dementia).

Power 3.1.7 software was used to calculate the sample size. The regressions we conducted to examine the impact of stigma on mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control included up to six predictors. The effect size was set to small (0.1). Based on an α of 0.05 and a power (1–β) of 0.95, a sample size of 132 adolescents was required. During the recruitment process, 423 adolescents with T1D were approached. Of these, 56 (13%) did not meet the inclusion criteria and 49 (12%) refused to participate due to time constraints. In the end, 318 adolescents participated, but 11 were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. The final sample size for this study was 307, with 135 participants in the preadolescence stage (≤13 years) and 172 in the postadolescence stage (>13 years), meeting the minimum sample size requirement.

2.2. Data Collection

A trained study assistant approached eligible adolescents when they regularly visited the outpatient clinics or attended summer camps organized by two hospitals. Pen-and-paper questionnaires were handed out to the participants at the scheduled appointment. To allow for the privacy of responses, adolescents completed the questionnaires in a meeting room without the presence of their guardians. When participants filled out the questionnaire, a study assistant was at their side to answer questions at any time.

All procedures performed in this study are under the Declaration of Helsinki. Eligible adolescents and their parents were informed about the study’s aims and methods. Adolescents signed assent forms before completing the survey. Additional written informed consent was acquired from a legal guardian if the participant was younger than 18 years old. The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University approved the study (number: 202309003-1).

2.3. Study Variables and Measures

2.3.1. Independent Variable: Stigma

2.3.1.1. Stigma

The T1D Stigma Assessment Scale (DSAS-1) initially developed by Browne et al. [5] and used to assess the perceived and experienced stigma for adolescents with T1D. Yang et al. [25] first prepared the Chinese version of the DSAS-1 and verified its reliability and validity. The Chinese version of the DSAS-1, consisting of 17 items, was divided into three subscales: treated differently, blame and judgment, and identity concerns. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”), with the total score ranging from 17 to 85 points. Higher scores indicate that adolescents perceived and experienced more diabetes-related stigma. Our calculations showed that Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.90 in this study.

2.3.2. Moderator: Intentional Self-Regulation

2.3.2.1. Intentional Self-Regulation

The selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) questionnaire was used to assess intentional self-regulation [26]. The scale consists of nine items and is divided into three subscales: elective SOC. Each item uses a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 7 (completely consistent), with a higher total score implying greater intentional self-regulation. The SOC has good construct validity (GFI = 0.96 and RMSEA = 0.046). The Cronbach’s α in this sample was 0.93.

2.3.3. Dependent Variables

2.3.3.1. Mental Well-Being

The WHO-five well-being index (WHO-5) was used to evaluate participant’s mental well-being. de Wit et al. [27] demonstrated the convergent validity of the WHO-5 in adolescents with T1D. The WHO-5 was conceptualized as a unidimensional measure that contains five items. How individuals have felt over the last 2 weeks was scored on a 6-point Likert scale (5 = “all the time” to 0 = “at no time”). The raw scores are multiplied by 4, from 0 (worst possible mental well-being) to 100 (best possible mental well-being). High scores imply better mental health. Moreover, a score <50 suggests mild to severe depressive symptoms and is an indication for further depression testing. In this study, the WHO-5 demonstrated acceptable reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.90.

2.3.3.2. Self-Management Competency

The Diabetes Skills Checklist TeenReport (DSC-T), developed by Papadakis et al. [11], assessed adolescents’ perceived competency in diabetes self-management. The DSC-T was a unidimensional measure representing a range of general diabetes management tasks. Evidence for the concurrent validity of the DSC-T was observed, as its total score showed a significant positive correlation with diabetes strengths. It comprises 14 items, and all items were measured with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). High scores imply greater perceived self-management competency. The Cronbach’s α of the DSC-T was 0.92 in the present study.

2.3.3.3. Glycemic Control

The HbA1c value was used to reflect the participant’s glycemic control. HbA1c values were measured from the venous blood samples on the day of the survey by a trained study assistant. An HbA1c level below 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) is considered optimal glycemic control for adolescents with T1D [28].

2.3.4. Covariates

Sociodemographic and diabetes-related information included the adolescent’s age, gender, residence, family income, parental education level, number of children in the family, insulin therapy method, and disease duration.

2.4. Data Analysis

All analyses were based on complete data and used SPSS version 22.0. We used means with standard deviations (SDs) and frequencies with percentages to describe continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Stigma among participants with different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were compared using Student’s t-tests.

A series of hierarchical regression models tested associations and moderations. We entered the main effect terms for stigma and intentional self-regulation in Step 1 and the two–way interaction of the main effect terms in Step 2. All independent variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity. Multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze the effect of stigma on depression symptoms. In all analyses, we controlled for demographic and clinical factors that have emerged in the t-tests as predictors of stigma. Moreover, subgroup analysis was also conducted regarding the participant’s age (≤13 years vs. >13 years). The test for interaction was employed to evaluate the joint association of stigma and age groups on outcome variables.

To explicate statistically significant stigma × intentional self-regulation interactions, we examined simple slopes using one SD above the mean to represent high intentional self-regulation and one SD below the mean to represent low intentional self-regulation. Furthermore, the Johnson–Neyman (J–N) technique was performed to identify the regions of significance along the continuous distributions of the stigma, where the impact of the stigma on outcomes of interest became significantly different for adolescents with low intentional self-regulation versus high intentional self-regulation. SPSS v.22.0 software with PROCESS v.3.3 model in a bootstrap approach was used to conduct simple slopes and J–N analysis [29].

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Associations With Stigma

In total, 307 participants were analyzed, with a mean age of 14.26 (SD: 4.46) years. Table 1 presents the sample’s sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and compares these characteristics with the stigma. The participants were mainly female (56%) and more than half (64%) had a monthly family income of $1375 or less. Fifty-one percent of the adolescents lived in rural areas and 34% had parents with a college education or higher. Participants without siblings accounted for 44%. Regarding their clinical characteristics, the adolescents surveyed reported 5.59 (SD: 3.65) years of disease duration on average. About half (53%) of the sample has been diagnosed with T1D for over 5 years and the majority (70%) received insulin treatment using the insulin pen. The mean HbA1c was 66 mmol/mol (8.2%) and 56% of the adolescents failed to achieve an HbA1c below 58 mmol/mol (7.5%). The HbA1c levels of participants in the preadolescent and postadolescent groups were 65 (8.1%) and 68 mmol/mol (8.4%), respectively.

| Characteristics | N (%) | Stigma (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Preadolescence (≤13) | 135 (44) | 35.13 ± 13.55 |

| Postadolescence (>13) | 172 (56) | 36.96 ± 13.58 |

| p-Value | — | 0.246 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 134 (44) | 36.37 ± 13.59 |

| Female | 173 (56) | 35.96 ± 13.59 |

| p-Value | — | 0.792 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural area | 157 (51) | 38.01 ± 13.32 |

| Urban area | 150 (49) | 34.20 ± 13.60 |

| p-Value | — | 0.014 |

| Family monthly income ($) | ||

| ≤1375 | 197 (64) | 36.71 ± 14.26 |

| >1375 | 110 (36) | 35.27 ± 12.71 |

| p-Value | — | 0.394 |

| Parental education level | ||

| High school diploma or lower | 202 (66) | 37.27 ± 13.40 |

| College degree or higher | 105 (34) | 33.97 ± 13.70 |

| p-Value | — | 0.043 |

| Single-child family | ||

| Yes | 134 (44) | 34.17 ± 13.11 |

| No | 173 (56) | 37.67 ± 13.76 |

| p-Value | — | 0.025 |

| Insulin therapy method | ||

| Insulin pen | 204 (66) | 36.14 ± 13.45 |

| Insulin pump | 103 (34) | 36.16 ± 13.94 |

| p-Value | — | 0.993 |

| Disease duration (years) | ||

| ≤5 | 145 (47) | 36.06 ± 13.69 |

| >5 | 162 (53) | 36.21 ± 13.50 |

| p-Value | — | 0.925 |

- Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and frequency (percentile).

The t-tests showed that residence and parental education were associated with stigma in adolescents with T1D. The stigma of participants who lived in rural areas was higher than those who lived in urban areas (t = 2.47, p = 0.014). Adolescents whose parents had a college degree or higher had lower stigma than participants with a high school degree or lower (t = 2.03, p = 0.043). Moreover, differences between adolescents from one-child families and multichild families emerged across stigma presentations, with those with siblings showing higher levels of stigma (t = −2.26, p = 0.014). However, stigma did not differ significantly among participants of different ages, genders, family incomes, insulin therapy methods, or disease duration.

3.2. Consequence of Stigma

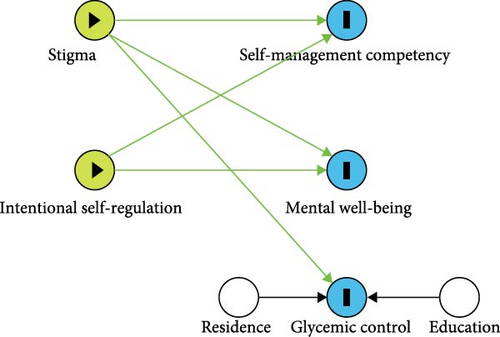

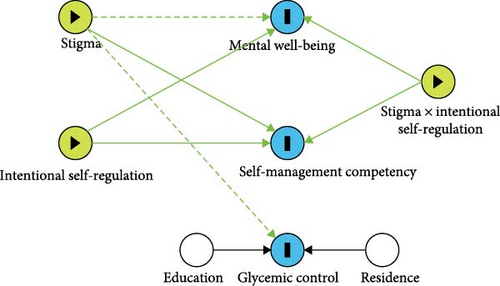

Complete results for the three hierarchical multiple regression models with mental well-being, self-management competency, and glycemic control are presented in Table 2. Figure 1A illustrates the associations between stigma and outcome variables, while Figure 1B shows the association after adding the interaction term between stigma and intentional self-regulation.

| Predictors | Model 1 (mental well-being) | Model 2 (self-management competency) | Model 3 (glycemic control)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Residence | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.32 | −0.12 | −1.98 ∗ |

| Parental education level | 0.04 | 0.67 | −0.09 | −1.74 | −0.17 | −2.82 ∗∗ |

| Single-child family | −0.06 | −1.08 | −0.08 | −1.57 | 0.07 | 1.19 |

| DSAS-1 | −0.26 | −4.88 ∗∗∗ | −0.17 | −3.29 ∗∗ | 0.12 | 2.14 ∗ |

| SOC | 0.33 | 6.22 ∗∗∗ | 0.42 | 8.26 ∗∗∗ | −0.05 | −0.83 |

| R2 | 0.19 | — | 0.24 | — | 0.10 | — |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Residence | −0.01 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 1.20 | −0.13 | −2.07 ∗ |

| Parental education level | 0.04 | 0.71 | −0.09 | −1.77 | −0.17 | −2.82 ∗∗ |

| Single-child family | −0.06 | −1.08 | −0.08 | −1.57 | 0.07 | 1.17 |

| DSAS-1 | −0.29 | −5.63 | −0.19 | −3.42 ∗∗∗ | 0.11 | 1.90 |

| SOC | 0.34 | 6.69 ∗∗∗ | 0.43 | 0.82 ∗∗∗ | −0.04 | −0.70 |

| DSAS-1 × SOC | 0.22 | 4.27 ∗∗∗ | 0.14 | 2.72 ∗∗ | 0.08 | 1.31 |

| R2 | 0.24 | — | 0.26 | — | 0.10 | — |

| R2 increase due to interaction | 0.05 ∗∗∗ | — | 0.02 ∗∗ | — | 0.01 | — |

- Note: Residence, parental education level, and number of children in the family are used as covariates.

- ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

- †Glycemic control is reflected by HbA1c levels.

In the model with mental well-being (Model 1-Step 1), stigma was negatively associated with mental well-being (β = −0.26, p < 0.001). Of 307 adolescents with T1D, 74 (24.1%) had mild to severe depressive symptoms. Logistic regression analysis revealed that adolescents with higher levels of stigma had a higher risk of mild to severe depressive symptoms (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: (1.03, 1.07), p < 0.001).

In the model evaluating self-management competency as the dependent variable (Model 2-Step 1), a negative association was observed between stigma and self-management competency (β = −0.17, p = 0.001) after controlling for sociodemographic variables associated with stigma (residence, parental education, and number of children in the family).

In the model with glycemic control (Model 3-Step 1), stigma was positively associated with HbA1c (β = 0.12, p = 0.034), suggesting that adolescents who perceived or experienced more stigma may have poorer glycemic control.

Subgroup analysis showed that age did not moderate the association between stigma and mental well-being, self-management competency, or glycemic control (Pinteraction = 0.064, 0.067, and 0.148, respectively). However, the association between stigma and glycemic control was statistically significant in the preadolescence group, but not in the postadolescence group (Table 3).

| Predictors | Model 1 (mental well-being) | Model 2 (self-management competency) | Model 3 (glycemic control)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Age (10–13) | ||||||

| Residence | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.13 | 1.61 | −0.16 | −1.89 |

| Parental education level | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.89 | −0.24 | −2.79 ∗∗ |

| Single-child family | −0.05 | −0.56 | 0.01 | 0.16 | −0.03 | −0.37 |

| DSAS-1 | −0.38 | −4.88 ∗∗∗ | −0.23 | −2.93 ∗∗ | 0.19 | 2.27 ∗ |

| SOC | 0.28 | 3.64 ∗∗∗ | 0.37 | 4.71 ∗∗∗ | 0.15 | 1.76 |

| R2 | 0.26 | — | 0.24 | — | 0.17 | — |

| Age (14–19) | ||||||

| Residence | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.60 | −0.08 | −0.91 |

| Parental education level | 0.07 | 0.85 | −0.05 | −0.68 | −0.06 | −0.77 |

| Single-child family | −0.07 | −0.93 | −0.14 | −1.96 | 0.20 | 2.36 ∗ |

| DSAS-1 | −0.15 | −2.03 ∗ | −0.16 | −2.3 ∗ | 0.11 | 1.35 |

| SOC | 0.34 | 4.72 ∗∗∗ | 0.49 | 7.47 ∗∗∗ | −0.23 | −2.90 ∗∗ |

| R2 | 0.16 | — | 0.30 | — | 0.14 | — |

- Note: Residence, parental education level, and number of children in the family are used as covariates.

- ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

- †Glycemic control is reflected by HbA1c levels.

3.3. Moderation Effect of Intentional Self-Regulation on Relationships Between Stigma and Relevant Outcomes

Stigma varied significantly depending on residence, parental education level, and number of children in the family (Table 1). Therefore, the simple slope and J–N analyses assigned those three variables as covariates. We also included adolescents’ age as a covariate because younger participants would interpret the questionnaires more differently than older participants.

3.3.1. Mental Well-Being

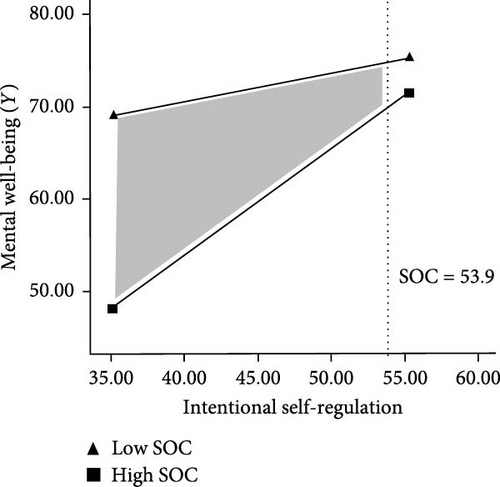

Table 2 shows a significant interaction between stigma and intentional self-regulation was observed in mental well-being (β = 0.22, p < 0.001). Simple slopes found that the slope of the line representing the associations between stigma and mental well-being was significant for those with low levels of intentional self-regulation (β = −0.77; 95%CI: −1.00, −0.54; p < 0.001), but not for those with high levels of intentional self-regulation (β = −0.14; 95%CI: −0.34, 0.06; p = 0.157). The results of the J–N analysis showed that the negative impact of stigma on mental well-being became insignificant when the SOC score was >53 (Figure 2).

3.3.2. Self-Management Competency

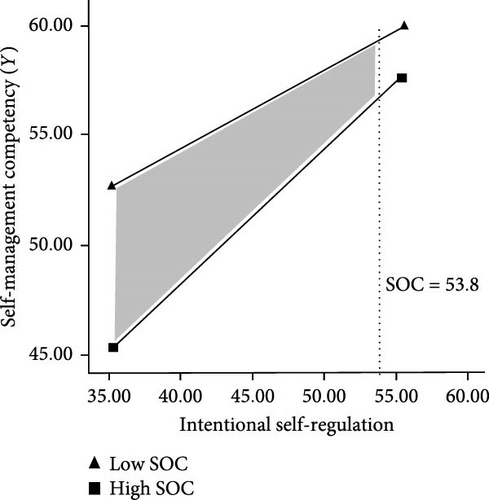

Results found a significant two-way interaction between stigma and intentional self-regulation (β = 0.14, p = 0.007). Simple slopes tests found that the slope of the line representing the associations between adolescent’s stigma and self-management competency was significant for those with low levels of intentional self-regulation (β = −0.27; 95%CI: −0.39, −0.148; p < 0.001), but not for those with high levels of intentional self-regulation (β = −0.08; 95%CI: −0.19, 0.02; p = 0.114). The results of the J–N analysis showed that the negative impact of stigma on self-management competency became insignificant when the SOC score was >53 (Figure 3).

3.3.3. Glycemic Control

Since no significant interaction effect was found between stigma and intentional self-regulation (β = 0.14, p = 0.007) in HbA1c, we did not perform the simple slopes test and J–N analysis. The results indicated that stigma may influence glycemic control regardless of the level of intentional self-regulation.

4. Discussion

While stigma has been associated with poor mental health in previous work, results from the present study suggest that this relationship remains unchanged when considering the social and cultural context of the East. The association between stigma and glycemic control was only found in the preadolescence group. Moreover, this is the first study to demonstrate the negative correlation between stigma and self-management competency in adolescents with T1D. We also examined the moderating effects of intentional self-regulation for the first time. In the context of high intentional self-regulation, the negative association of stigma with mental well-being and self-management competency became nonsignificant.

Adolescents with T1D who participated in this study reported a moderate degree of stigma, higher than the results found in Australia [5]. China has the lowest incidence of T1D worldwide and low public awareness, leading to social stereotypes [30]. Moreover, discrimination practices, such as not being admitted to universities, could exacerbate adolescent’s stigma [30]. Knowing how stigma affects adolescents through sociodemographic factors would help us gain a further understanding of T1D stigma as a whole. In line with previous studies [31], we found that adolescents who lived in rural areas perceived or experienced more stigma than those who lived in urban areas. As expected, participants with siblings reported greater levels of stigma. Healthy siblings could exacerbate the patient’s feelings of inferiority and injustice. In addition, significant differences were found in levels of stigma among adolescents whose parents had different levels of education. Adolescents with more educated parents would perceive more parental support and were less prone to stigma [32].

Having identified the presence of stigma among adolescents with T1D, we then assessed the effects that stigma might have on relevant patient outcomes. We found that stigma was negatively associated with mental well-being in adolescents with T1D, consistent with previous chronic illness stigma literature [7, 33]. Further logistic regression showed that stigma significantly predicted mild to severe depressive symptoms. Similarly, in a recent meta-analysis, a moderate positive correlation between type 2 diabetes stigma and depressive symptoms was found [34]. Modified labeling theory argues that anticipated discrimination and self-labeling, as specific manifestations of stigma, would lead to depression and poor mental well-being [35]. In this study, higher stigma was also associated with decreased self-management competency. This result was partially confirmed by Brazeau’s study, which showed that the higher the diabetes-related stigma, the lower management self-efficacy [7]. Increased perceived and experienced stigmatization may damage adolescents’ self-esteem and heighten internalized shame, reducing their efficacy in managing diabetes [36]. Moreover, because T1D is a concealable illness, concerns about unexpected illness disclosure related to insulin injection and glucose monitoring may affect self-management competency. In a qualitative study, adolescents with T1D described their experience of being questioned and driven away in public because their insulin injection behaviors were mistaken for illegal drug use [3]. Confirmation of a negative association between stigma and glycemic control was a significant result, coinciding with previous studies conducted in Western countries [7, 13, 14]. The reason for this association is multifaceted. The well-documented link between mental well-being and glycemic control suggests that stigma may increase depressive symptoms, thereby increasing glycemic fluctuations [37]. Moreover, the negative effect of stigma on self-management competency may contribute to higher glycemic levels [11]. However, we did not observe an association between stigma and HbA1c in postadolescence group. Hormonal changes during late adolescence make glycemic control more challenging [38], which might obscure the effect of stigma on HbA1c. More research is needed to explore the association between stigma and glycemic control in older adolescents.

Another significant finding of our study pertains to the moderation effect of intentional self-regulation between stigma and mental well-being. More specifically, adolescents with higher levels of intentional self-regulation and severe stigma demonstrated better mental well-being than adolescents who lacked intentional self-regulation and suffered severe stigma. According to Baltes’s SOC model [23], adolescents can achieve positive development by adopting intentional self-regulation strategies to regulate their relationship with the environment in stressful situations. Although the moderating effects of intentional self-regulation had not been examined in previous studies, the association between intentional self-regulation and mental health is well documented. In Gestsdottir’s study [39], intentional self-regulation was negatively associated with depressive symptoms among middle adolescents. Zhou et al. [19] reported that all components of intentional self-regulation could predict nursing students’ mental well-being. Moreover, we found that intentional self-regulation moderated the association between stigma and self-management competency. Similarly, Richman and Lattanner [16] proposed that self-regulation could break the relationship between discrimination and healthy behaviors. A meta-review confirmed the effect of self-regulation interventions on adherence to chronic disease medication [40]. Our findings suggest that interventions aimed at improving mental health and self-management competency may benefit from targeting intentional self-regulation prior to stigma, given that stigma does not appear to impair mental health and self-management competency in adolescents with high intentional self-regulation.

Our results indicated that the stigma may adversely affect adolescents’ mental health and self-management. As applied to clinical practice, we suggest that healthcare providers openly discuss stigmatizing perceptions and experiences with adolescents with T1D to identify the sources of stigma (family members, peers, health providers, and social). Moreover, judgment-free and non-biased language should be used when communicating with this population. It is further recommended that healthcare providers give education to correct misperceptions about T1D and organize patient contact to reduce stigma. The finding of the interaction between stigma and intentional self-regulation highlighted that strengthening an individual’s intentional self-regulation ability could help cope with mental distress and improve an adolescent’s self-management competency. Healthcare providers can implement self-regulation interventions for adolescents, such as social and personal skills training, exercise-based programs, and mindfulness interventions [41].

4.1. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, a causal relationship between stigma, intentional self-regulation, and outcome variables cannot be proven, given its cross-sectional nature. Second, the study sample was entirely Asian; although it enables cross-cultural comparisons, the results should be interpreted cautiously. Third, participants were conveniently recruited, which may be prone to biases. Adolescents with stigma may have been less likely to participate. Fourth, we used self-administered questionnaires, which may lead to shared method variance and social desirability response. To improve the reliability of the results, we recommend a multimodal approach to assessing stigma symptoms, such as interviews and observations.

5. Conclusion

In this study, adolescents with T1D reported a moderate degree of stigma, negatively associated with mental health and self-management competency. The association between stigma and glycemic control was only found in the preadolescence group. More studies are required to understand sources, generation, and development of stigma. In addition, we found that intentional self-regulation moderates the relationship of stigma with mental well-being and self-management competency. These results indicated that self-regulation–based training should be an essential component of further interventions to reduce stigma and improve mental health and disease management.

Disclosure

The preliminary abstract of this manuscript was presented at the 50th Annual Conference of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) 2024 [42].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 72204125, to Dan Luo) and the Philosophy and Social Sciences Project of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Grant 24XRC001, to Dan Luo).

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.