Nurses’ Lifestyle Behaviors, Work-Related Stress, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Abstract

Background: The nursing profession exposes nurses to work-related stress and presents a big challenge to adhering to healthy lifestyle behaviors. This collectively increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Aim: To assess the association between work-related stress with lifestyle behaviors and CVD risk among Jordanian nurses.

Methods: This study used a cross-sectional descriptive design. A convenient sample of 165 nurses was recruited from three different Jordanian hospitals. Data were collected using self-reported questionnaires. Blood samples were withdrawn to assess the lipid profiles of the participants. Work-related stress was assessed using a 5-item Job Stress Scale, healthy lifestyle behaviors were assessed using Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP II) to measure, and CVD risk was calculated using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator Plus. Then, data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient, and linear multiple regression.

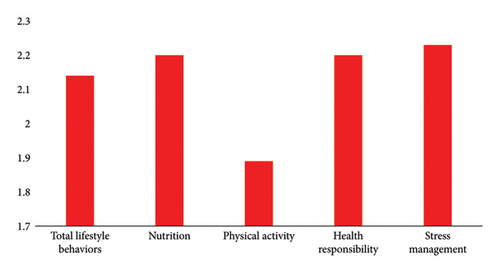

Results: This study showed that 55.2% had a high work-related stress score. In addition, the nurses’ level of adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors was at a moderate level (M = 2.14, SD = 0.40), with the lowest average score for physical activity (M = 1.89, SD = 0.60). Most of the participants (75.2%) were observed in the CVD high-risk category. Current experience had a significant positive correlation with the lifetime risk of developing CVD (r = 0.19, p > 0.05) and negative correlations with both work-related stress (r = −0.21, p > 0.01) and stress management subscale score (r = −0.18, p > 0.05). Furthermore, sex was the only significant predictor of healthy lifestyle behaviors (β = −0.19, p < 0.001) and CVD risk (β = 0.35, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: The results of this study signify the importance of increasing awareness about the risk of developing CVD among nurses. Thus, healthcare leaders, managers, policymakers, and decision-makers should focus on improving healthy lifestyle behaviors among nurses and decreasing stress levels at work among Jordanian nurses, which will positively reflect on nurses’ health and lower the risk of developing CVD.

1. Introduction and Background

Nurses comprise the largest workforce in healthcare. Around 50% of healthcare professionals globally are nurses [1]. Nurses perform tasks full of situations that cause wear, tension, and self-carelessness [2]. Stress at work is one of the most serious occupational health risk factors for professionals globally [3]. Across all the healthcare professions, nurses are the healthcare professionals who have suffered the most from work-related stress over the past decade [4]. Nurses are prone to high levels of work-related stress, adversely affecting their psychological, physical, and emotional health [5, 6].

The nursing profession is highly stressful because nurses are dealing with serious diseases and patient deaths [7]. In addition, nurses are responsible for providing care and services that are ethical, attentive, empathetic, cooperative, and culturally sensitive to patients and their families. Furthermore, the demands to provide high-quality patient care with insufficient resources lead to increased stress at work among the nurses [8]. Consequently, stressed nurses are more prone to illness and injury, which causes absenteeism and reduced efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity [9].

Work-related stress is one of the main contributors to several health problems among nurses due to their profession [10]. Nurses are exposed to diseases associated with stress [11]. Stress triggered by working conditions causes physical and psychological tension, as a result of the imbalance between the personal expectations and the demands or the goals of the job [11]. Several factors contribute to increasing the level of work-related stress among nurses, such as sociodemographic characteristics, personal behavior, and work-environment conditions, including the type of working unit, shift working, number of hours worked per week, work experience, job satisfaction, and an assigned position in the institution [12–14].

The nursing profession is most frequently affected by work-related disorders. The majority of absences from work were due to medical leaves, where cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the fourth most common cause for these absences [15]. According to Chou et al. [16], there is a significant relationship between high work-related stress and poor cardiovascular health among nurses due to low physical activity practices. Nobahar and Razavi [17] found that nurses had a high risk of developing CVD and a high incidence of CVD risk factors.

A cross-sectional study was conducted by Dias et al. [18] among 324 nurses to investigate CVD risk among nursing staff at a public hospital in Brazil. The study’s findings showed that 96% of nurses have a low risk of developing CVD for ten years. Similarly, Jahromi [19] found that the ten-year risk of CVD was low among nurses in Iran. Furthermore, male nurses had a greater risk than females of developing CVD [20]. Vetter et al. [21] found that nurses who work frequently on rotating shifts have an elevated risk of developing CVD. However, Reed et al. [22] found that systolic blood pressure (SBP) was higher in nurses working fixed shifts compared to rotating shifts.

Long working hours and CVD risk were significantly associated. Furthermore, long working hours can enhance the following unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as higher levels of alcohol and cigarette smoking, decreased leisure activities, limited relaxation and opportunities for physical activity, and decreased quality of sleep [18]. Also, nurses who work in closed departments have a high risk of developing CVDs [23]. In addition, several CVD risk factors, including obesity/overweight, poor psychological well-being, smoking, high cholesterol, hypertension (HTN), and diabetes, were prevalent among nurses [22]. The prevalence of CVD risk considerably increases as nurses get older, increase their education, and gain work experience [24]. Furthermore, the incidence of HTN, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hypercholesterolemia was significantly greater among married nurses when compared to unmarried counterparts [24].

A meta-analysis conducted by Khani et al. [23] showed that, during the past two decades, a sedentary lifestyle, lack of physical activity, family history, elevated SBP, elevated diastolic blood pressure (DBP), overweight, and alcohol consumption are the major risk factors of CVD among nurses worldwide. Nurses’ decisions regarding their lifestyles have an important impact on their general health, including the risk of developing CVD and the quality of their lives [25]. Furthermore, the well-being and health of nurses may have a direct influence on the patient’s care and the general population’s health [26].

Few studies assessed the association between work-related stress with lifestyle behaviors and CVD risk in Jordan. For example, Aldalaykeh et al. [27] assessed nurses’ lifestyle (sleep, dietary habits, smoking status, and physical activity) among Jordanian nurses. The study results showed that around 58% of nurses were overweight or obese, and 41.9% had unhealthy eating behaviors. In another study conducted in Jordan, 50.2% of nurses exhibited unhealthy eating behaviors [28]. In addition, Suleiman et al. [29] study findings showed that the prevalence of poor sleep quality was 92.1% among nurses in Jordan.

Despite the large body of literature on work-related stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and CVD risk, the associations of these variables are not yet fully delineated among Jordanian nurses. De Sio et al. [30] underscore the need for effective risk assessment and preventive measures against work-related stress, highlighting systemic vulnerabilities that require urgent attention. In addition, Gmayinaam et al. [31] provide a comparative analysis of work-related stress among nurses, revealing marked disparities and emphasizing the necessity for context-specific assessment. Furthermore, Jelen et al. [32] document the prevalence and factors aggravating work-related stress among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, illustrating how acute stressors in high-pressure environments can lead to severe mental health challenges. Although these studies addressed several dimensions of work-related stress among nurses, there is still a gap in understanding how lifestyle behaviors, work-related stress, and CVD risk are associated. This, in turn, substantiates the significance of our current study in developing a more comprehensive understanding of these variables together. Thus, this study aimed to assess the association between work-related stress with lifestyle behaviors and CVD risk among Jordanian nurses.

The specific objectives are to (1) assess the correlation between sociodemographic characteristics, work-related stress, lifestyle behaviors, and CVD risk among nurses; (2) assess the differences in CVD risk factors among nurses based on work-related stress and lifestyle behaviors; and (3) identify the variables that are contributing to the CVD risk among nurses.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A cross-sectional descriptive design was utilized to recruit a sample of nurses from three different hospitals in Jordan.

2.2. Sample

Nurses who had at least an associate degree in nursing, worked for at least 1 year in the selected hospitals, and had not been diagnosed with CVD were invited to participate. A total of 165 nurses were recruited conveniently between October and December 2023 for this study. The sample size was calculated using G∗power [33], based on a medium effect size (0.15), a power of 0.80, a level of significance (p < 0.05), and 16 predictors.

2.3. Ethical Approval

Before the study began, institutional review board (IRB) approval (IRB#: 359/2023) and approvals from the selected hospitals were obtained. Before data collection, written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The participants were asked to respond to the study questionnaires, and they were informed that they had to fast for at least 8 h the next day or two before a sample of their blood was withdrawn for this study. To maintain participant anonymity, the blood samples were identified only by the researchers, who also had access to the participants’ names. The numerical codes were implemented for the paper survey to maintain the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Demographic Characteristics

Data were collected on participants’ age, sex, marital status, number of children, education, number of sleep hours per night, years of experience at the current place, total years of experience in nursing, type of hospital, type of unit or ward, type of shift work, and the number of working hours per shift.

2.4.2. Job Stress Scale

Work-related stress was assessed using the Job Stress Scale adapted by Lambert et al. [34] from Crank et al. [35] study, which was developed to assess how frequently stressful situations disturb employees. The Job Stress Scale contains five items that measure the level of work-related stress using a five-point Likert scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The total score was calculated by summing all items together; the total score ranges between 5 and 25, with a higher score indicating a higher work-related stress.

The reliability of the Job Stress Scale was supported, and Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.82 [35]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.81.

The Job Stress Scale was translated using the translation and back translation processes by experts in the English and Arabic languages after obtaining written consent from the author of the instruments. Additionally, the content validity of the Arabic version of the Job Stress Scale was assessed by a panel of six experts. The Arabic version of the Job Stress Scale demonstrated strong content validity.

2.4.3. Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP II)—A Modified Version

A modified version of the HPLP II [36] was used to measure lifestyle behaviors among nurses. The original version of HPLP II contains 52 items with six subscales to measure lifestyle behaviors in six dimensions (spiritual growth, interpersonal relationships, physical activity, nutrition, health responsibility, and stress management). In the current study, four dimensions were used (physical activity, nutrition, health responsibility, and stress management), which contain 34 items to measure the frequency of health-promoting behaviors among nurses. Participants’ responses to the items indicate the frequency of engaging in the behaviors, ranging from Never = 1 to Routinely = 4. The total score of the HPLP II is calculated by obtaining the mean of the responses, which ranged from 1 to 4, with a higher score indicating a good level of adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors. The scores of the subscales can be obtained by calculating the means of the relevant items [36]. The reliability of the HPLP II scale was supported, and Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98 indicates that the scale is highly reliable, and the construct validity was supported [37]. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale in this study was 0.89. The reliabilities of the subscales used in this study ranged between 0.63 and 0.81.

2.5. The Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Estimator

The ASCVD Risk Estimator is used to assess CVD risk among participants in this study. The ASCVD is a valid measure of CVD risk that was developed by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [38, 39]. The ASCVD Risk Estimator predicts the 10-year and lifetime risk of ASCVD, which includes coronary mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and fatal or nonfatal stroke [40].

The ASCVD Risk Estimator is calculated based on several variables, such as current age, sex, race, systolic and DBP, lipid profile (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol), history of diabetes, smoking, HTN treatment, statin treatment, and aspirin therapy. After accounting for all variables, the lifetime risk for ASCVD is classified as Low (5%), Borderline (5%–7.4%), Intermediate (7.5%–19.9%), and High (20%) [41].

A blood sample was withdrawn from the participants, and they were requested to fast for 8–12 h before blood withdrawal, to assess their lipid profile. The samples were withdrawn by an experienced nurse then they were sent to the laboratory within one to two hours of sampling. The blood samples were preserved in an icebox. The participants’ SBP and DBP were assessed using a manual sphygmomanometer (3k Desk Model Mercurial Sphygmomanometer, Japan) and recorded in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). After being seated for 5 min, BP measures were obtained from the left arm.

2.6. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (Version 25, Armonk, NY) was used to analyze data. Descriptive statistics (mean, frequency, percentages, and standard deviations) were employed to summarize the demographic characteristics of the participants. For statistical significance, a p value of < 0.05 was employed. Before analysis, the dataset was checked for missing data; no missing data were found. In addition, the possible confounders (demographic characteristics) were adjusted for by including them in the multiple regression analysis models. The independent t-test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess the differences in the outcome variables based on demographic characteristics. As well, a Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationships between the demographic characteristics and the main study variables and to examine the relationships between the main study variables. In addition, a series of backward elimination regression analyses were carried out to identify the predictors of the main study variables (work-related stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and the lifetime of CVD risk).

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the categorical demographic characteristics and CVD risk factors. The total number of participants was 165, and the majority of the participants were unmarried (52.7%) females (72.7%) with a bachelor’s degree (85.5%). In addition, most of the participants worked rotating (day and night) shifts during the last month (45.5%).

| Variables | Categories | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 45 (27.3%) |

| Female | 120 (72.7%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 78 (47.3%) |

| Not married | 87 (52.7%) | |

| Education | Associate degree | 9 (5.5%) |

| BSN | 141 (85.5%) | |

| MSN | 15 (9.1%) | |

| Smoking | Current | 53 (32.1%) |

| Former | 10 (6.1%) | |

| Never | 102 (61.8%) | |

| Unit/ward | Medical–surgical | 33 (20%) |

| Critical care unit | 113 (68.5%) | |

| Other | 19 (11.5%) | |

| Type of hospital | Governmental | 79 (47.9%) |

| Teaching | 56 (33.9%) | |

| Private | 30 (18.2%) | |

| Work shift | Day | 66 (40.0%) |

| Night | 24 (14.5%) | |

| Both | 75 (45.5%) | |

| Number of working hours | 8 h | 73 (44.2%) |

| 12 h | 28 (17%) | |

| 16 h | 64 (38.8%) | |

| History of diabetes | Yes | 2 (1.2%) |

| No | 163 (98.8%) | |

| On hypertension treatment | Yes | 2 (1.2%) |

| No | 163 (98.8%) | |

| On statin therapy | Yes | 1 (0.6%) |

| No | 164 (99.4%) | |

| On aspirin therapy | Yes | 7 (4.2%) |

| No | 158 (95.8%) | |

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the noncategorical variables. The mean (M) age of participants was 30.70 years, standard deviation (SD) = 7.20. The mean number of sleeping hours per night reported by the study participants was M 6.57, SD = 1.60. In addition, the work-related stress scores ranged from 7 to 25 (M = 18.08, SD = 3.40), and the median was 19. Work-related stress scores were categorized into high or low based on the median score. The majority of the participants (55.2%) were frequently identified as having a high work-related stress score. The SBP of the participants ranged from 90 to 157 mmHg (M = 116.47, SD = 11.60), and the DBP of the participants ranged from 50 to 94 mmHg (M = 72.69, SD = 9.005). The mean total cholesterol of the participants was M = 175.87 mg/dL, SD = 34.23.

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 23 | 56 | 30.70 | 7.20 |

| Number of children | 0 | 6 | 1.01 | 1.60 |

| Sleeping hours | 3.5 | 12 | 6.57 | 1.60 |

| Current experience | 0 | 22 | 4.71 | 5.10 |

| Total experience | 1 | 26 | 7.41 | 6.10 |

| Work-related stress | 7 | 25 | 18.08 | 3.40 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 90 | 157 | 116.47 | 11.60 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 50 | 94 | 72.69 | 9.005 |

| Total cholesterol | 114 | 320 | 175.87 | 34.23 |

| HDL cholesterol | 22.80 | 79.90 | 51.16 | 12.40 |

| LDL cholesterol | 42 | 227.00 | 108.77 | 29.40 |

| ASCVD | 5% | 93.00% | 31.03% | 15.81 |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1 shows the healthy lifestyle total scale scores and their subscales. The total healthy lifestyle behaviors scale score ranged from 1.38 to 3.21 (M = 2.14, SD = 0.40); the mean score of the subscales was also calculated; the highest average of the subscale was the stress management subscale (M = 2.23, SD of 0.50); and the lowest score was for the physical activity subscale (M = 1.89, SD = 0.60). Table 3 shows the CVD risk among participants; most of the participants (75.2%) were observed in the high-risk category, followed by the intermediate risk (21.8%) category. Only 3% of the participants had a borderline risk for CVD.

| Categories | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Low-risk (< 5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Borderline risk (5%–7.4%) | 5 (3%) |

| Intermediate risk (7.5%–19.9%) | 36 (21.8%) |

| High risk (≥ 20%) | 124 (75.2%) |

The Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationships among the main study variables (Table 4). Sleeping hours per night did not have any significant correlation with the other main study variables. Current experience had significant positive correlations with lifetime risk of developing CVD (r = 0.19, p > 0.05) and negative correlations with both work-related stress (r = −0.21, p > 0.01) and stress management subscale score (r = −0.18, p > 0.05). In addition, there was a positive correlation between total experience and lifetime risk of developing CVD (r = 0.27, p > 0.01). Also, there were significant negative correlations of the total experience with work-related stress (r = −0.25, p > 0.01), physical activity (r = −0.17, p > 0.05), and stress management (r = −0.17, p > 0.05).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of children | 1 | 0.04 | 0.59∗∗ | 0.70∗∗ | −0.25∗∗ | −0.13 | 0.00 | −0.17∗ | −0.07 | −0.18∗ | 0.69∗∗ | 0.19∗ |

| 2. Sleeping hours | 1 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| 3. Current experience | 1 | 0.80∗∗ | −0.21∗∗ | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.18∗ | 0.71∗∗ | 0.19∗ | ||

| 4. Total experience | 1 | −0.25∗∗ | −0.15 | −0.03 | −0.17∗ | −0.10 | −0.17∗ | 0.90∗∗ | 0.27∗∗ | |||

| 5. Work-related stress | 1 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.27∗∗ | 0.03 | ||||

| 6. Lifestyle behaviors | 1 | 0.77∗∗ | 0.79∗∗ | 0.84∗∗ | 0.72∗∗ | −0.17∗ | −0.04 | |||||

| 7. Nutrition | 1 | 0.48∗∗ | 0.55∗∗ | 0.42∗∗ | −0.02 | −0.06 | ||||||

| 8. Physical activity | 1 | 0.58∗∗ | 0.39∗∗ | −0.20∗∗ | −0.02 | |||||||

| 9. Health responsibility | 1 | 0.50∗∗ | −0.12 | −0.01 | ||||||||

| 10. Stress management | 1 | −0.20∗ | −0.05 | |||||||||

| 11. Age | 1 | 0.26∗∗ | ||||||||||

| 12. Lifetime CVD risk | 1 |

- ∗Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

- ∗∗Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 5 represents the multiple regression analyses used to predict lifestyle behaviors and lifetime CVD risk. A series of backward elimination regression analyses were carried out to identify the predictor variables and then a simple linear regression model was built using these predictor variables. The results showed that age, sex, type of unit (workplace), type of shift, education, sleeping hours, type of hospital, and total experience significantly predicted healthy lifestyle behaviors (F (7, 157) = 2.16, p < 0.05, Adjusted R2 = 0.05). The findings showed that sex was the only significant predictor (β = −0.19, p < 0.001). In addition, these variables significantly predicted CVD risk (F (3, 161) = 15.23, p < 0.001, Adjusted R2 = 0.21); only sex (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) was significantly predicting CVD risk.

| Lifestyle behaviors | Lifetime CVD risk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 2.13 | 0.30 | 7.15 | 0.000 | 16.59 | 5.15 | 3.22 | 0.002 | ||

| Age | −0.004 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.77 | 0.44 | |||||

| Sex | −0.17 | 0.08 | −0.19 | −2.24 | 0.03 | 12.32 | 2.52 | 0.35 | 4.90 | 0.000 |

| Type of unit (workplace) | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −1.04 | 0.30 | |||||

| Type of shift | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 1.23 | 0.22 | −2.24 | 1.32 | −0.13 | −1.69 | 0.093 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 1.17 | 0.24 | |||||

| Sleeping hours | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.66 | |||||

| Type of hospital | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 1.57 | 0.12 | |||||

| Total experience | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 2.27 | 0.25 | |||||

| Model summary | F (7, 157) = 2.16, p < 0.05, adjusted R2 = 0.05 | F (3, 161) = 15.23, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.21 | ||||||||

- Note: B: unstandardized coefficient, β: standardized coefficient.

- Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

4. Discussion

The results of the current study showed that nurses had a high level of work-related stress. This was consistent with previous studies [12, 42–44]. In contrast, other studies showed that nurses have moderate levels of work-related stress [45–48]. These differences in the levels of work-related stress could be explained by the different settings and countries in each study, the different instruments that were used to assess the level of work-related stress, the different sample sizes, organizational cultural variations, and the differences in the perceived level of work-related stress among the participants.

In addition, there was a significant negative correlation between work-related stress and years of experience at the current place and total years of experience in this study. The results are similar to those found by Hajjar [42] and Anand and Mejid [46]. As nurses get more experience at their current workplace, this will improve their abilities to handle a variety of situations, medical conditions, and patients from different cultural backgrounds and increase their awareness of practice workload. It also leads nurses to cope with their workplace, which lowers stress levels.

In this study, we assessed the healthy lifestyle behaviors of nurses. The results of the current study showed that nurses generally have a moderate level of engagement in healthy lifestyle behaviors. This finding was consistent with other studies [49–53]. There are multiple barriers to engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors; these barriers include the tasks and responsibilities, organizational factors, environmental factors such as lack of healthy and fresh food and/or facilities to store the food, personal factors such as inadequate motivation levels and self-efficacy, and social factors such as the dietary behaviors [54, 55].

The results of the current study showed that nurses generally have a high risk of developing CVD; more than 75% of the nurses who participated in this study have a > 20% chance of developing CVD in their lifetime. The result is similar to the study conducted by Chou et al. [16]. On the other hand, Olubiyi et al. [56] findings were incongruent with the current study’s findings. This variation in the prevalence of the risk of developing CVD among nurses between studies could be explained by the different settings and different instruments (categories and ratings) that were used to assess the risk of developing CVD. Furthermore, there is a significant positive correlation between CVD risk and years of experience at the current place and total years in the nursing profession. The result is consistent with the study conducted by Khani et al. [23], which found that the prevalence of CVD risk factors considerably increases as nurses get more work experience.

In the current study, we assessed the association between work-related stress and lifestyle behaviors. The results showed that there is no significant correlation between work-related stress and lifestyle behaviors. The result is inconsistent with the study by Heikkilä et al. [57], which showed that work-related stress was associated with unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. In addition, Torquati et al. [58] found that strategies to modify healthy lifestyle behaviors were associated with a reduction in work-related stress.

We assumed a possible association between work-related stress and CVD risk among nurses. Evidence from the studies implies nurses are suffering from significant levels of work-related stress [18, 59–61]. However, the results of the current study showed that there is no significant correlation between work-related stress and CVD risk, which is inconsistent with the previous studies [59–61]. In the current study, we assessed the association between lifestyle behaviors and CVD risk among nurses. The results showed that there is no significant correlation between lifestyle behaviors and CVD. This result is inconsistent with the studies [62, 63], which showed that nurses who follow healthy lifestyle behaviors showed improvement in mental and cardiovascular health.

These inconsistencies with previous studies could be explained by several variables that include, but are not limited to, cultural and environmental influences of the nurses participating in this study; workplace policies and job demands that differ between countries and workplaces; differences in the availability of health-promoting programs; and variations in the methodologies such as the designs, participants, and assessment tools.

In addition, the linear regression analysis model showed that almost 5% of the variance in the perceived healthy lifestyle behaviors was explained by age, sex, type of unit, type of shift, education, number of sleeping hours, and the type of hospital. This was aligned with the Aldalaykeh et al. [27] study, which was conducted in Jordan. The results of the current study showed that almost 21% of the variance in the lifetime CVD risk was explained by sex, type of shift, and total years of experience. The findings indicated only that sex was significantly predicting the lifetime CVD risk, where male nurses reported a higher risk of developing CVD than females. This is aligned with Khani et al. [23] and Dias et al. [18]. Heredity and environmental variables are the primary causes of sex-based differences [64].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between work-related stress, lifestyle behaviors, and CVD risk among Jordanian nurses. The current study contributes significantly to the existing literature by introducing a new correlation between the study variables. This adds valuable insights to specify the factors that produce stress at work, affect the nurse’s lifestyle behaviors, and increase the risk of developing CVD. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study which include convenience sampling and a relatively small sample size, an assessment of work-related stress using an instrument not designed specifically for nurses, an assessment of healthy lifestyle behaviors using specific dimensions of the HPLP II, and social desirability issues that are associated with self-reported questionnaires which may result in bias. Furthermore, the nature of the cross-sectional design prevented the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships among the study variables. In addition, these confounding variables may have resulted in the low power of the existing models in explaining the variance of the outcome variables.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has provided significant findings about the assessment of work-related stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and the lifetime CVD risk among nurses. The findings indicate that nurses generally reported high levels of work-related stress. In addition, the participants of the current study have a moderate level of adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors. As well, the average risk of developing lifetime CVD was high among the participants.

Notably, the study revealed no significant correlations between work-related stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and lifetime CVD risk. However, current findings indicate that sex is a significant predictor of healthy lifestyle behaviors and lifetime CVD risk among nurses.

Future research is recommended to widen the opportunity for more comprehensive investigations and advance knowledge of work-related stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors using the full version of the HPLP II, and CVD risk among nurses. This could be applied by using different assessment tools, such as assessing stress using cortisol levels in blood, hair, or saliva, recruiting nurses from widespread areas of practice, increasing sample size, assessing nursing coping styles, and conducting experimental studies.

Nurses should be encouraged to adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors and stress management strategies. In addition, nursing managers are advised to create a working environment that promotes nurses’ health and enhances their productivity and quality of care by modifying and developing policies related to healthy behaviors at work such as increasing the healthy food choices in the cafeteria, developing a physical exercise program for nurses, conducting stress management sessions, allowing nurses to take a nap during the night shift, and conducting a smoking cessation program for nurses.

Finally, healthcare leaders, managers, policymakers, and decision-makers should focus on improving healthy lifestyle behaviors among nurses and decreasing stress levels at work among Jordanian nurses, which will positively reflect on nurses’ health and lower the risk of developing CVD.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by a student thesis research grant (#359/2023) from the Jordan University of Science and Technology.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a student thesis research grant from the Jordan University of Science and Technology. The authors would also like to thank nurses for their support and time spent completing surveys.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author (T.N.A.-D.). The data are not publicly available due to (restrictions, e.g., their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).