Festuca Grass (Festuca festuca) Management: A Key to Sustainable Resources Management in Borena-Sayint Worehimenu National Park (BSWNP)

Abstract

Festuca grass, a multipurpose and vital resource, is experiencing crises of sustainability and degradation due to increased demand and mismanagement. Through a survey research approach, this study aimed to develop sustainable management and utilization strategies for Festuca grass. We employed purposive and random sampling techniques for data collection, focusing on the Festuca grass potential in Borena-Sayint Worehimenu National Park. Interviews, key informant surveys, focus group discussions, and field observations were also conducted. We employed quantitative and qualitative data analysis techniques to ensure a comprehensive approach to deriving insights from the collected data. The findings indicate that Festuca grass has a lifespan of two to four years and fully matures within two years. Products derived from Festuca grass vary according to the maturity level. The results also highlight the demand for Festuca grass and the potential availability of market demand. Harvesting frequency, inappropriate management practices, biased resource sharing, and unauthorized exploitation are basic challenges related to grass resource sustainability. The establishment of certified user groups, domestication of private stocks, revision of resource-sharing protocols, and periodic monitoring are among the possible potential strategic utilization options identified by user groups. A modified strategic framework for the sustainable management and utilization of Festuca grass was developed. This framework outlines four dominant management clusters that are interconnected with each other. Sustainable management of Festuca grass contributes to both environmental conservation and community wellbeing. It advocates for inclusive, community-based approaches that balance ecological preservation with socioeconomic needs. The sustainability of Festuca grass resources is precarious and could face a significant decline or total loss if the current management practices remain unchanged in the coming decades. To ensure the effective utilization and management of Festuca grass, it is imperative to implement periodic resource monitoring, conduct stakeholder meetings, and apply a sustainable management framework. The responsibility for sustaining Festuca grass resources lies with governmental organizations, academic and research institutions, nongovernmental organizations, professional associations, and user communities.

1. Introduction

National parks are crucial for biodiversity conservation on a global scale, as they help protect ecosystems from encroachment and misuse. Sustainable Development Goal 13 (2030)—focused on climate actions—explores national parks’ geophysical ecology and biodiversity conservation. However, there is a gap in site- and commodity-specific studies on the sustainable management and utilization of specific floristic species [1]. National parks in Ethiopia showcase natural beauty and diverse landscapes, promoting sustainability and biodiversity conservation. These protected areas attract tourists and contribute to Ethiopia’s top tourist destination status. However, sustainability challenges arise due to anthropogenic pressures, necessitating species- and site-specific studies to ensure ecological and economic sustainability [2].

Borena-Sayint Worehimenu National Park (BSWNP), formerly “Denkoro Chaka State Reserve”, is in the southern Wollo Zone in northern Ethiopia [3, 4]. It was established as a national park in 2009 with a history of protection dating back to the 14th century (1428–1461), potentially leading to Africa’s oldest conservation practice [5]. This species has gained significant attention for its biodiversity, particularly since 1952, and has continued to be protected and conserved with local community assistance [6]. The park covers an area of 15,262 ha of land with an altitudinal range between 1900 and 4280 m above the sea level [7]. It is known for its rich biodiversity, containing approximately 354 and 63 endemic plant species. It is also a habitat for approximately 30 animals (including larger mammals, amphibians, reptiles, smaller mammals of rodents, and bats), 77 registered bird species and diverse floristic species, mainly Festuca grass [3, 8]. Despite its dominance and multiple roles, the Festuca grass in this park currently faces sustainability, requiring research on conservation policy.

Festuca grass (full scientific name) is a perennial herb and afroalpine vegetation that is dominantly distributed in parks. Festuca is a genus name for approximately 450 species that grow mainly in temperate and subtropical regions extending to mountains in the tropics. It is characterized by erect culms approximately 1 m tall with dense tussocks [9]. It grows within the altitudinal range of 3000–4100 m.a.sl [10, 11]. Festuca grass is endemic to Ethiopia and is distributed and commonly used around the highlands of Gondar, Wollo, and North Shoa Administrative Zones. It is one of the park’s resources that creates a strong connection between the park and the surrounding community. The grass is a highly valued and multipurpose species. It can be used for plastering houses and baskets, making different household tools (such as wickerwork, Mesob1), rope making, floor mats, fodder, rain huts, whips (Jiraf2), and as a source of forage for animals and income from its sale. BSWNP is a potential source of Festuca grass, where farmers around the park use it for various uses with special allowances from the respective bodies. However, comprehensive ecological and socioeconomic studies are lacking to ensure the sustainability of the species, as it is a keystone species in the park.

The local communities around the park have a positive attitude and preference for the traditional use of the park’s resources through the harmony of conservation and development [3, 12]. However, the increased demands for social services and values of resources within parks due to population growth are pushing factors that pressure equitable resource sharing [13, 14]. Currently, parks are under pressure from sustainability [3, 7, 15]. Poor infrastructural development [16], lack of natural buffer zones [17], environmental degradation [18], human–wildlife conflicts [19, 20], and ever-increasing demand for expansion of agricultural lands are significant constraints contributing to the degradation and depletion of park resources. To solve all the abovementioned challenges, a policy brief should be issued through the research and synthesis of research on the current potential and challenges.

Given the combined impact of the aforementioned constraints, Festuca grass, a versatile park resource, is currently facing significant sustainability and degradation challenges due to its mismanagement. Thus, survey research was planned to develop sustainable management and utilization strategies based on evaluations of current resource status and utilization schemes. This research focused on (a) exploring the resource potential, maturity, and harvesting strategies of Festuca grass in the park; (b) classifying the current utilization and products of Festuca grass in the park; (c) investigating the market conditions and benefit-sharing strategies for Festuca grass in the park; (d) scrutinizing the challenges of Festuca grass in the park; and (e) designing the sustainable management and utilization of Festuca grass with community participation in the park.

These findings are crucial for long-term conservation and utilization policies in national parks because Festuca grass is an essential resource for the local, national, and international communities. Understanding its ecological and financial significance is essential for promoting grass regeneration, guaranteeing optimal harvesting, and promoting sustainable harvesting. Knowing how currently used, for example, for medicinal purposes and cattle grazing, helps to inform conservation and economic initiatives. Understanding its benefit sharing and market dynamics encourages environmental preservation and community involvement. Targeted interventions are made possible by addressing issues such as overharvesting and climate change, which guarantees sustainability over the long run and the preservation of biodiversity. Despite the versatile uses and degradation of Festuca grass resources, studies on existing utilization strategies and their synergies with resource sustainability are limited. Therefore, it is expected to generate a scientifically investigated Festuca grass utilization approach that will potentially support experts and policymakers in developing feasible management plans and guidelines.

2. Methods and Materials

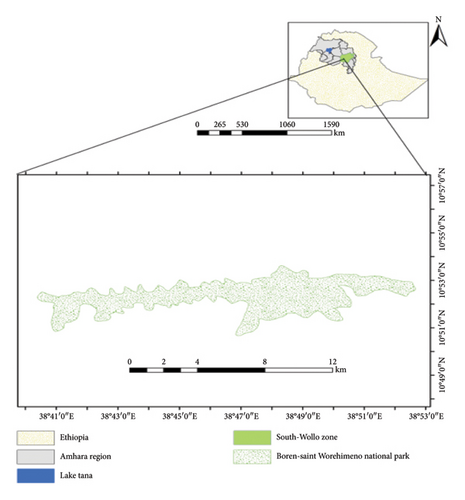

2.1. Description of the Study Area

BSWNP (Figure 1) is located in the South Wollo Zone of the Amhara Regional State, 600 km from Addis Ababa (the capital city of the country) and 300 km from the Bahir-Dar (regional capital). Geographically, the park lies between 10°50′ 45.4″ and 10°53′ 58.3″ N latitude and between 38°40′ 28.4″ and 38°54′ 49″ E longitude, with altitudinal ranges of 1900–3700 m above the sea level. The Park spans the boundaries of three districts: Borena, Sayint, and Mehal Sayint. The area is endowed with a bimodal rainfall pattern. Climatically, the area is characterized by a bimodal rainfall distribution pattern (long and main rainy season from June to September and a minor rainy season from March to April). The mean monthly rainfall ranges between 9.50 and 235.70 mm. The mean monthly maximum temperature ranges between 17.8°C (August) and 24.4°C (March), with the mean monthly minimum temperature ranging between 9.5°C (November) and 11.8°C (May).

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Purposive and random sampling procedures were applied to select the intended locations and respondents. The park was selected purposively. A general overview of the Festuca grass potential was determined through a reconnaissance survey [21]. Based on the reconnaissance survey results, the resource user kebeles around the park were clustered into three categories based on the Festuca grass potential [22]. Accordingly, respondents were selected randomly with the help of scouts and development agents. Elderly farmers, scouts, and park experts were selected purposively as key informants for the interviews. In addition, members of the focus group were selected purposively.

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from primary and secondary sources through combinations of interviews, key informant surveys, and focus group discussions. Following the information saturation point approach, a total of 71 Festuca grass user farmers from 3 kebeles (24 farmers per kebele) were interviewed [23]. Since only males have been engaged in harvesting grass, females were not included in the interview. In cases where the household was headed by a female, either male family members were involved in the collection of grass or they sold their share to others. Key informant survey (KIS) was conducted with six individuals, and three (one per kebele) focus group discussions were held with 6–8 individuals from farmers, scouts, and experts [22]. Moreover, actual field observations were performed to complement and triangulate the data collected through questionnaires and verify resource distributions and status, mechanisms of harvesting, the existence of illegal practices, and management strategies applied within each target kebeles.

2.3. Methods of Data Analysis

For the quantitative data collected through interviews, we employed Statistical Products and Service Solutions (SPSS) Ver. 25/26. These data were gathered from research questions related to maturity, harvesting age, potential product types, marketing potential, and strategies, as well as determinants and prospects of the Festuca grass resource. On the other hand, the qualitative data gathered from key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations were analyzed following the content analysis method and narrated and summarized in text format.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The interviews were conducted with a group of participants, all of whom were male. The ages of the participants varied, with the youngest being 30 years old and the oldest being nearly 58 years old. A significant portion of the participants (60%) in the interview had completed primary school. In contrast, 28% of the respondents had traditional or informal educational experiences that equip them to read and write. The remaining 12% of the respondents were those who did not receive formal or informal education, meaning that were unable to read or write.

3.2. Maturity of Grass, Harvesting, and Resource Potentials

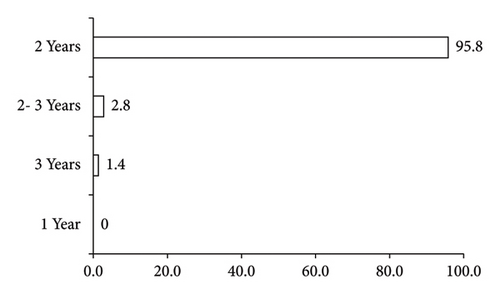

Based on the abovementioned results, farmers agreed that the maturity of fescue grass occurred within 2 years of the first harvest (Figure 2). All the Festuca grass user group representatives confirmed that it takes 2 years to reach full maturity. Therefore, ensuring the sustainability of Festuca grass harvesting must be achieved when full physiological maturity is achieved [24].

Based on the type of establishment, nature of site conditions [25], climatic conditions, disturbance situations/levels, and management interventions, the lifespan of Festuca grass varies from 2 to 4 years [26].

3.3. Types of Products (Utilization Clusters)

The user group has identified several benefits of Festuca grass (Table 1). They gather the grass from parks for personal consumption or for resale. All community members who live within and around the park’s boundaries are recognized as users of its resources, benefiting from and contributing to the shared natural and recreational amenities.

| No | Types of products | Maturity period in years | Harvesting month |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feed forage for animals as grass | Less than or 1 year (both when green & mature) | Mid-February–mid March, when green |

| 2 | House ceiling/covering | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 3 | Broom | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 4 | Sifet/Mesob1 | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 5 | Rope making | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 6 | Rain hut | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 7 | Festuca rope | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 8 | Floor mat | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 9 | Plastering house | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

| 10 | Festuca baskets | After 2 years | Mid-February–mid March |

- 1Sifet, local house utilize used for serving foods (similar to big trays).

The representatives of the grass user groups outline the dry period before the start of rain (mid-February–mid-March) as the appropriate harvesting time of year, and they also underline the total harvesting/clear-cutting protocol. If Festuca grass is not harvested when it matures, the grass will die without replacing itself in the future, as indicated in Figure 3.

Several factors must be considered before harvesting. The maturity level, stem strength, weather conditions (rainy or dry), prediction time of the next rainfall event, and harvesting technique should be considered during harvesting. Specifically, grass must be harvested when it is dry enough (checked by physical touching and observations) [25]. In addition to grass characteristics, circumstances that disturb the wildlife of the park, such as maintaining optimum grass for grass-fed wild animals, fixing harvesting time with their feeding, and resting reproductive times, should be avoided [27]. This approach is used to avoid the possibility of breakdown and crumbling during harvest as well as for clean harvesting.

3.4. Market Availability and Benefit-Sharing Protocols

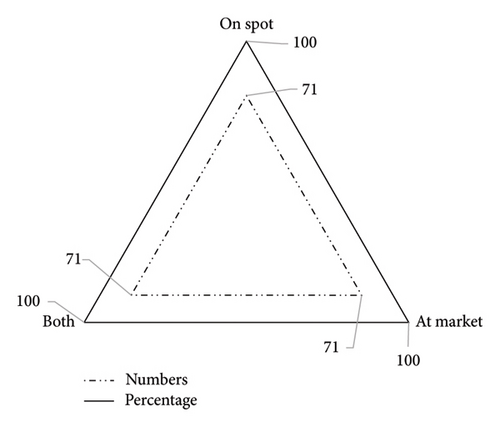

The availability of a market for grass is not considered an issue for Festuca grass user groups (Figure 4). The main constraint regarding grass is its availability. Fundamentally, they have two types of marketing mechanisms. They identified three marketing locations for transactions of the grass: on-spot selling (buyers collect grass from the spot of harvesting), producers selling the grass on the market (users collect and take the grass to market in search of buyers), and/or combinations of the two.

Even though it is difficult to determine the selling price of grass, all the users agreed that its price is expensive. To improve market management, enhance the income of users and create a healthy market chain, a producer consumer linkage will be planned and implemented [12, 28]. In addition, certifying user groups as Festuca Grass users’ associations will enhance trust among user groups and a sense of ownership [13, 29, 30]. As they do not have standard units (cubic meters or kilograms) for grass, it is difficult to set the selling price of grass.

The benefit-sharing protocol they are applying and being governed is by using local and unregistered associational structures (called “limat budin3”) created/established for running agricultural and watershed management interventions. This means the total resources are first clustered/divided into user group localities following the nearest proximity approach. After the patches are known, each locality is divided equally (spatial site of the area) into several “limat budins”. After that, the so-called limat budin leaders divide their part into user members on their team. However, most of the users indicated the availability of unfair resource sharing between a single team member (“limat budins”) and from one limat budin to another limat budin. Another thing user groups did not agree on was the allocation of resource patches following the nearest proximity approach.

Concerning this approach, sites that receive/get patches with good grass stands were happy and wanted to proceed with them, while the others who obtained less productive sites/spots wanted to change this approach to resource sharing. Therefore, frequent dialogue and discussion are needed with all user members. Deciding whether the approach is right or wrong without having discussions and reaching a common level of understanding will result in negative consequences [18].

3.5. Challenges of Sustainable Utilization of Festuca grass

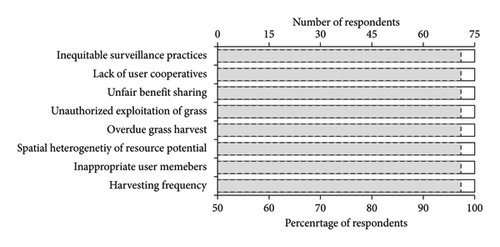

User groups identified several critical constraints (Figures 5 and 6) that support the sustainability of grass resources by creating dissatisfaction among users and weakening their sense of ownership and responsibility. The problems identified by user groups were clustered into eight dominant classes. Specifically, the exclusion criteria for individuals were as follows: harvesting frequency, inappropriate user members, spatial heterogeneity of resource potential, overdue grass harvesting, unauthorized exploitation of grass, unfair resource sharing, lack of user cooperatives, and inequitable surveillance practices.

The graph (Figure 5) highlights several key challenges in utilizing Festuca grass, as perceived by respondents. High levels of concern regarding surveillance practices suggest a need for more transparent and fair monitoring systems to ensure equitable resource management. The absence of cooperatives indicates a significant barrier to collective action and resource sharing, which could hinder sustainable utilization efforts. Perceived inequities in benefit distribution may lead to conflicts and reduced cooperation among stakeholders, affecting overall resource management. Unauthorized exploitation points to weak enforcement of regulations, necessitating stronger governance and community engagement to protect the resource. Variability in resource potential across different areas suggests the need for tailored management strategies that consider local conditions and capacities. Issues with user group composition highlight the importance of inclusive and representative stakeholder involvement to ensure effective management. Concerns about overharvesting frequency indicate a need for guidelines and best practices to balance utilization with sustainability. These insights can guide policymakers, researchers, and practitioners in developing strategies to address these challenges and promote sustainable management of Festuca grass.

3.6. Strategic Utilization Options

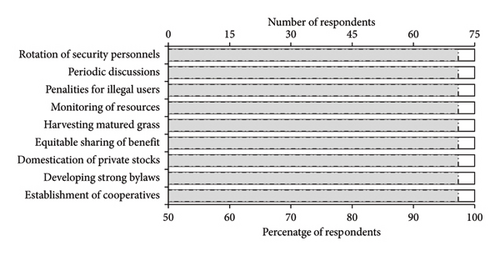

Having participatory discussions and developing a sustainable and productive resource utilization plan are fruitful strategic tasks for any resource. Accordingly, nine interventions were identified for the implementation of the Festuca grass user groups on the BSWNP (Figure 7). These interventions range from the establishment of certified user groups for control to the promotion of private grass stocks to reduce pressure on the park.

4. Discussion

Harvesting of Festuca grass must be performed during a dry period or when there should not be rain during harvesting. This process helps to prevent the occurrence of stem decay and dieback due to the accumulation of water under the stems and rhizomes of the grass. Moreover, the time needed for the next rain startup must be predicted to determine the harvesting time. The harvested stumps/culms should receive enough moisture after harvesting. Moisture is vital for new shoot development or recruitment. In addition, critical care must be taken during harvesting. The grass must not be subjected to stem splitting or uprooting during harvesting, and it must be conducted with sharp tools so that no grass stem will be allowed to persist or that each and all patches and stumps must be harvested in time and via an appropriate protocol.

To ensure the sustainability of any plant species, whether it is annual, biennial, or perennial, knowing the normal physiological life cycle is one determinant scenario. The application of any management intervention is dependent on the life cycle [31, 32]. For perennial plant/grass species, knowledge of the life cycle becomes the primary factor for fixing the rotation period of harvesting [33].

Fundamentally, perennial grass species that reproduce through rhizomes (root-like underground plant parts) and coppicing harvesting must be conducted when the grass species sets flowers. If such species are allowed to persist after flowering/seed set, the species might suffer total dieback or species loss [34].

From a technical point of view, equal and fair allocation of all sites for all user groups is better than the nearest proximity-sharing approach [20, 35]. The nearest proximity approach will have two negative effects on the sustainability of grass resources. First, those groups that receive weak-performing (less productive) grass patches will not be willing to harvest. Second, the groups that obtain the most productive patches with wider area coverage are likely to be forced to harvest and leave some patches [30, 36]. Therefore, both scenarios result in stand dieback and grass loss. This means that if Festuca grass is not harvested at maturity, it will die [29, 37].

The unanimous identification of these listed constraints by every respondent not only highlights the widespread recognition of challenges but also underscores how serious and deeply ingrained they are. This collective agreement suggests that these problems have permeated extensively and deeply into the system, demanding urgent focus. The fact that these issues have been fully recognized implies a shared understanding and experience among the respondents, further emphasizing the urgency of solutions. Those challenges identified in our study are in line with the findings of [38]. Therefore, such a broad agreement ought to act as a call for stakeholders to address these deep-rooted problems promptly and effectively.

To ensure the sustainability of grass resources, user groups must overcome significant obstacles. Unauthorized use, unequal distribution, and irregular harvesting are some of these restrictions. Maintaining the health of resources requires prompt management and the involvement of skilled persons. Conflicts and discontent can result from unequal distribution. Effective resource management requires cooperative efforts and open government. Transparent governance, cooperative arrangements, and improved user education are necessary to address these limitations. For the benefit of all parties involved, we may improve the sustainability of grass resources by encouraging ethical behavior and shared ownership. The authors in [2, 39] demonstrated that African national parks and floristic species face the challenge of sustainability, mainly due to anthropogenic pressures.

Periodic and participatory monitoring helps in determining management (weather, harvesting, or others) [40, 41]. The relationship between the guards and the surrounding community was strongly attached, and the individuals who arrived at the family hood attachment and guards were subjected to less and/or no punishment for those who denied the rules and regulations of park management due to courtesy. Therefore, their placement is temporary, and they exercise their tasks accordingly [36, 37, 42].

Developing strong bylaws and harvesting matured patches were supplementary interventions for sustaining Festuca grass resources [42]. A delay in harvesting matured grass patches will result in stand drying and dieback [33]; moreover, the availability of a strong bylaw signed by all members will healthily govern them, and the existence of a strong bylaw will support putting strong penalties for [24, 43, 44].

The resource-sharing protocol should be modified following specific conditions, as resource status (both in area coverage and productivity) varies from location to location (spot to spot) within the park and contributes to sustainability by facilitating equitable benefit-sharing approaches. This means that the existing nearest proximity resource sharing must be changed. This modality contributes to the death of stumps due to a lack of harvesting because of ample resource availability [7, 13, 45]. Conducting periodic meetings and discussions among user groups, park managers, squats, and guards has a positive impact on the sustainability of resources, as a result of which weaknesses and strengths are indicated and future directions are predicted [6, 7, 46]. The identified strategic utilization interventions can be further classified into three main leading categories, namely, technical, administrative, and collaborative or networking.

The technical strategies included intervention inquiries, professional interventions, and recommendations. Conducting periodic resource monitoring, on-time harvesting of mature grasses, and domestication of grass to enhance private stocks are facilitations that can be conducted through the involvement of experts in the field.

Administrative solutions are implementations that necessitate the application of decisions to enhance the sustainability of given resources. Building a strategy for periodically shifting security personnel (scouts and guards) from zone to zone, developing strong and agreed-upon bylaws, and formulating procedures and mechanisms to penalize illegal actions and exclude unauthorized users are strategies that require administrative decisions for implementing sustainable management plans.

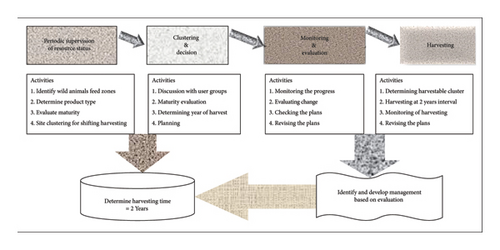

5. Modified Sustainable Management Strategic Frameworks

Based on the abovementioned agreements and results, the following utilization framework indicator plan was developed (Figure 8). The indicative utilization framework is developed by dividing overall utilization activities into four basic components. These components also have distinct activities to be implemented. The framework has been modified to include detailed steps in each stage of sustainable management, emphasizing periodic supervision, and evaluation every 2 years. Specific actions such as identifying wild animals’ feed zones, determining product types, and site clustering for shifting harvesting have been added. The modification was necessary to improve accuracy in resource management, ensure sustainability, and adapt to specific case study requirements that were not met by existing frameworks. This ensures a more precise and effective management strategy. The modified framework brought a structured approach with clear intervals for assessment (every 2 years) and specific action points for managing resources sustainably. This resulted in enhanced accuracy in sustainability assessments and improved stakeholder engagement. The modification was initiated by new insights into resource management needs, feedback from previous strategic applications, and particular objectives of the study setup that required a tailored approach. This proactive approach aimed to enhance the framework’s applicability and effectiveness. The methodology section has been updated to include a detailed explanation of the modifications. This includes a step-by-step description of the changes made, the rationale behind each modification, and how these were implemented in the study. The modification adds novelty by introducing innovative elements, such as new sustainability indicators and a unique approach to stakeholder engagement. This contributes to the study’s originality and advances the field of sustainable management.

According to the abovementioned framework (Figure 8), overall, Festuca grass management and utilization plans and tasks must be divided into four dominant management clusters that are strongly interconnected with each other. As shown in the graph (Figure 8), one cluster powerfully contributes to the other cluster and one cluster is the result of the other.

Periodic supervision and resource status evaluation: under this management cluster identification of wild animal feed zones, potential product type determination, checking/evaluating maturity, and clustering the resource sites/spots for harvesting are the dominant activities to be implemented and conducted.

Clustering resources spots based on the results of task one and making decisions, following the successful accomplishment of the first task, the user groups must shift to the tasks in the second cluster. In this category, discussions with users to implement the results of the first task, evaluate maturity (product type varies), determine the year of harvest, and plan for harvest and utilization are basic tasks of this task. If the individual activities of the abovementioned two clusters were accomplished, it is possible to determine the harvesting age of the Festuca grass at this stage.

Monitoring and evaluating the results and consequences of the abovementioned two tasks for every natural resource management and utilization intervention monitoring and evaluation of past interventions and activities significantly contribute to securing sustainability. Accordingly, monitoring progress, evaluating changes due to the above interventions, checking the progress of plans against the intended direction, and revising the plans (if necessary) are the leading tasks of this stage. Harvesting was conducted by determining the harvesting season and setting appropriate harvesting techniques; this is the final stage of the utilization framework.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The implications of the study reach beyond the immediate context of Festuca grass management, encompassing broader environmental conservation and community wellbeing. By emphasizing the importance of sustainable Festuca grass management, this study advocates for practices that not only preserve the local ecosystem but also safeguard the livelihoods of the communities reliant on this vital resource. The proposed interventions, such as establishing certified user groups and promoting private grass stocks, have the potential to create a sense of ownership and responsibility among the local populace, leading to more effective and equitable resource utilization. Ultimately, the study’s implications emphasize the necessity of inclusive, community-based approaches to natural resource management that strike a balance between ecological preservation and the socioeconomic needs of the surrounding communities.

Based on the findings of the study, the following recommendations are proposed for sustainable Festuca grass management. Periodic monitoring and evaluation of Festuca grass were performed to evaluate its resource status and maturity and appropriate harvesting techniques were selected. Certified user groups should be established, and private grass stocks should be promoted to reduce pressure on park resources and enhance market management. Strong bylaws and penalties for unauthorized exploitation should be developed to ensure fair resource sharing and sustainability. Regular meetings and discussions should be held among stakeholders to address challenges and strengthen collaboration. Shift toward effective Festuca grass management through the inclusion of professional interventions, decision-making processes, and networking strategies. A modified sustainable management strategic framework should be followed and implemented. The sustainability of Festuca grass resources is at risk and may experience a significant decline or complete loss if current management practices are not improved in the coming decades. To ensure effective utilization and management, it is crucial to implement periodic resource monitoring, hold stakeholder meetings, and apply a sustainable management framework. The responsibility for sustaining Festuca grass resources falls on governmental organizations, academic and research institutions, nongovernmental organizations, professional associations, and user communities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

We thank Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) for financial and administrative support and logistical organization. We thank farmers and resource user groups of the study sites for allowing us to work with them.

Endnotes

1A traditional picnic basket used for storing and serving injera, the Ethiopian flatbread. It symbolizes unity, prosperity, and cultural heritage.

2A cordage material utilized by young herders for managing livestock and by agricultural workers during plowing operations to drive oxen.

3Limat budin: residence proximity–based farmers’ association with 25–30 farmers in a single group for agricultural and natural resources management and utilization

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.