Knowledge of Kidney Disease Among Allied Health Sciences Undergraduates: A Cross-Sectional Study in the University of Cape Coast

Abstract

Introduction: Knowledge of kidney disease (KD) is an essential element that is needed in the scope of every healthcare professional. This study assessed the level of awareness and understanding of allied health sciences undergraduates of University of Cape Coast regarding KDs and their risk factors.

Methodology: Among the regular allied health sciences undergraduates of the University of Cape Coast, a cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2022 to June 2022. A well-structured questionnaire on knowledge of KDs and their risk factors was administered to consented participants. Data were analyzed accordingly using R Studio statistical software version 2022.02.3.

Results: The study involved 383 participants (the majority being males (52.7%)) with an average age of 22.23 ± 3.03 years. Age (p < 0.001), year of study (p < 0.001), program of study (p < 0.001), frequency of 30 min of exercise per week (p = 0.002), and body mass index (p = 0.023) showed statistically significant differences between males and females. The mean knowledge score of KD was 20.86 ± 3.88 (out of a maximum score of 27) with the majority of study participants having a high knowledge of KD (61.9% (237/383)). High knowledge level was observed for types and stages, diagnosis, and risk factors for KD (76.8% (3.84/5), 75.3% (5.27/7), and 81.6% (8.98/11), respectively) while moderate knowledge level was observed for signs and symptoms (69.3% (2.77/4)). Multivariate analysis showed that participants were found to be more knowledgeable about KDs if they indicated taking alcohol (OR = 5.96; 95% CI = 2.01–22.35; p = 0.003), being in second (OR = 3.27; 95% CI = 1.22–9.02; p = 0.020) or fourth (OR = 4.72; 95% CI = 1.63–14.37; p = 0.005) year of study, or classified themselves as being underweight (OR = 3.93; 95% CI = 1.22–15.85; p = 0.033). Students reporting alcohol use had almost six times higher odds of high KD awareness compared to those who did not report alcohol intake (OR = 5.96, 95% C = 2.01–22.35, p = 0.003).

Conclusion: This study revealed an adequate knowledge level of KDs and their risk factors among allied health sciences undergraduates. However, an inadequate knowledge of its signs and symptoms was observed indicating a need for improved training.

1. Introduction

Kidney disease (KD) is a significant global public and clinical health problem [1, 2]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic KD (CKD) are associated with poor quality of life, high healthcare expenses, and serious adverse health outcomes [1, 3]. AKI is mostly caused by diarrheal disease with dehydration, infectious diseases (malaria, dengue, yellow fever, leptospirosis, tetanus, and human immunodeficiency virus), animal venom, septic abortion, renal ischemia, sepsis, and sometimes nephrotoxic drug [4]. Studies have stated that the prevalence of CKD is higher in developing countries than in the developed world and is commonly caused by chronic glomerulonephritis and systemic hypertension [5].

Over 10% of individuals worldwide suffer from CKD, and this number rises to 50% in high-risk subpopulations such as those with diabetes mellitus and hypertension [6]. Poor control of major CKD risk factors, particularly diabetes mellitus and hypertension, is also partly responsible for the high incidence of CKD. These factors include delayed health-seeking behavior, lack of access to excellent primary health services, and use of traditional herbal medicine to treat these conditions [6–8]. Additionally, an acute decrease in glomerular filtration rate is a risk factor for adverse clinical outcomes as well as the development and progression of CKD [9].

Tahir et al. observed knowledge gaps in KD among medical trainees and practitioners [10]. Improved training on kidney physiology, pathology, prevention, risk assessment, diagnosis, and interdisciplinary management approaches is vital during the training of future allied health professionals. However, there has been no study in Ghana performed to assess the knowledge levels of KDs and their risk factors among allied health sciences undergraduates who would in no time pass out to practice in the field of healthcare. Thus, this study assessed the knowledge of KDs and their associated risk factors among allied health sciences undergraduates, expecting that the findings will be useful in determining constructive approaches to improve their health education on KDs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Site, Design, Population, and Sample Size

A cross-sectional study was employed to assess the level of knowledge about KDs and their risk factors among allied health sciences undergraduates at the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. The study was conducted from March 2022 to June 2022. A simple random sampling technique was employed to select a total of 383 participants in order to guarantee an unbiased representation of the study population, allow generalization of results to the target population, and avoid selection bias that may arise from other nonprobability sampling techniques. The study population included all regular allied health sciences undergraduates at the University of Cape Coast. The study participants were randomly selected from the study population using a number sequence ensuring every student had an equal chance of being selected independently of other students.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Regular allied health sciences undergraduates at the University of Cape Coast were eligible for the study. Non-allied health sciences undergraduates were excluded. Further, postgraduates and sandwich allied health sciences undergraduates were excluded.

2.3. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Department of Medical Laboratory Science, University of Cape Coast, and the institutional review board of the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital (Ref. No.: CCTHERC/RS/EC/2017/13). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki protocols on research ethics. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants before recruitment, after giving a detailed education on the basis, aims, and justification of this study. All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations [11]. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the entire study.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Study Instrument

A well-structured questionnaire was designed from a systematic literature review of similar studies on KDs and their risk factors [10, 12–14]. The questionnaire content was reviewed by three experts in the area and the final version of the instrument consisted of 38 items written in English. The questionnaire was categorized into five domains: sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (11 items), knowledge on types and stages of KDs (5 items), knowledge on signs and symptoms of KDs (4 items), knowledge on the diagnosis of KDs (7 items), and knowledge on risk factors of KDs (11 items) (Appendix 1). The 38-item questionnaire featured standardized options from which participants chose their answers. The total score regarding types and stages, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and risk factors for KD was 27. The overall scores of each respondent were converted to percentages to classify respondents’ knowledge as low knowledge (< 50%), moderate knowledge (50%–74%), and high knowledge (≥ 75%) as employed in a similar study by Mohd Noor et al. [15].

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

Participants were randomly recruited, after providing them a detailed education regarding the research and obtaining informed consent. Depending on the participant’s preference, a Google form questionnaire or printed questionnaire was administered to assess their knowledge.

2.6. Data Analysis

Initial entry and organization of data were done using Microsoft Excel 2016. The data were then coded and analyzed using R Studio statistical software Version 2022. 02. 3. The internal consistency was determined and an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.760 was obtained. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to verify the normality of variables. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondents’ characteristics and responses to survey items. Categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations. Differences between groups were assessed by Student’s T-test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to explore significant factors associated with overall knowledge of KDs based on respondent characteristics using odds ratio (OR). All analyses were done at a 95% confidence interval and p values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Self-Rated Characteristics of Participants

Among 383 participants, the average age was 22.23 ± 3.03 years. The majority were ranged between 21 and 30 years (71.5%) (Table 1). Out of 383, 52.7% (202/383) were males. Nearly 44% of participants were enrolled in physician assistant studies. Fourth-year students comprised 33.2%. Nearly 99% of participants were nonsmokers while 91% were nonalcoholic (Table 1). Some participants (15.9%) indicated having a family history of chronic disease. Age, year of study, program of study, frequency of doing exercise for 30 min per week, and self-description of body weight were found to have statistically significant differences between males and females (Table 1).

| Variable | Total N = 383 | Gender | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female n = 181 | Male n = 202 | |||

| Mean age | 22.23 ± 3.03 | 21.36 ± 2.8 | 23.00 ± 3.1 | < 0.001 ∗ |

| Age groups | < 0.001 ∗ | |||

| ≤ 20 | 99 (25.9) | 69 (38.1) | 30 (14.9) | |

| 21–30 | 274 (71.5) | 109 (60.2) | 165 (81.7) | |

| > 30 | 10 (2.6) | 3 (1.7) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Year of study | 0.023 | |||

| First | 57 (14.9) | 37 (20.4) | 20 (9.9) | |

| Second | 75 (19.6) | 37 (20.4) | 38 (19.0) | |

| Third | 124 (32.4) | 54 (29.8) | 70 (35.0) | |

| Fourth | 127 (33.1) | 53 (29.4) | 74 (37.0) | |

| Program of study | < 0.001 ∗ | |||

| Biomedical science | 29 (7.6) | 17 (9.4) | 12 (5.9) | |

| Clinical nutrition and dietetics | 39 (10.2) | 31 (17.0) | 8 (4.0) | |

| Health information management | 24 (6.3) | 14 (7.7) | 10 (5.0) | |

| Medical imaging and sonography | 50 (13.1) | 19 (10.0) | 31 (15.0) | |

| Medical laboratory science | 53 (13.8) | 15 (8.3) | 38 (19.0) | |

| Optometry | 18 (4.7) | 9 (5.0) | 9 (4.5) | |

| Physician assistant studies | 170 (44.4) | 76 (42.0) | 94 (47.0) | |

| Possession of valid health insurance | 0.574 | |||

| Yes | 82 (21.4) | 36 (19.9) | 46 (22.8) | |

| No | 301 (78.6) | 145 (80.1) | 156 (77.2) | |

| Smoking status | 0.437 | |||

| Yes | 5 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.0) | |

| No | 379 (98.7) | 180 (99.4) | 198 (98.0) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.712 | |||

| Yes | 35 (9.1) | 166 (91.7) | 182 (90.1) | |

| No | 348 (90.9) | 15 (8.3) | 20 (9.9) | |

| Frequency of doing exercises for 30 min per week | 0.002 | |||

| 0–2 times | 248 (64.8) | 133 (73.5) | 115 (57.0) | |

| 3–4 times | 88 (23.0) | 29 (16.0) | 59 (29.0) | |

| > 4 times | 45 (12.3) | 19 (10.5) | 28 (14.0) | |

| Self-classification of lifestyle | 0.600 | |||

| Not stressful | 55 (14.4) | 26 (14.0) | 29 (14.4) | |

| Relatively stressful | 246 (64.2) | 112 (62.0) | 134 (66.3) | |

| Very stressful | 82 (21.4) | 43 (24.0) | 39 (19.3) | |

| Family history of chronic diseasea | 0.073 | |||

| Don’t know | 35 (9.2) | 16 (8.8) | 19 (9.4) | |

| No | 287 (74.9) | 128 (70.7) | 159 (78.7) | |

| Yes | 61 (15.9) | 37 (20.5) | 24 (11.9) | |

| Self-description of body weight | 0.023 | |||

| Underweight | 29 (7.6) | 19 (10.5) | 10 (5.0) | |

| Normal | 314 (82.0) | 138 (76.2) | 176 (87.1) | |

| Obese | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Overweight | 37 (9.6) | 23 (12.7) | 14 (6.9) | |

- aChronic diseases indicated by respondents were either kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia.

- ∗p values were calculated using the chi-square test. Bold p values are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

3.2. Level of Knowledge of Kidney Diseases Among Participants

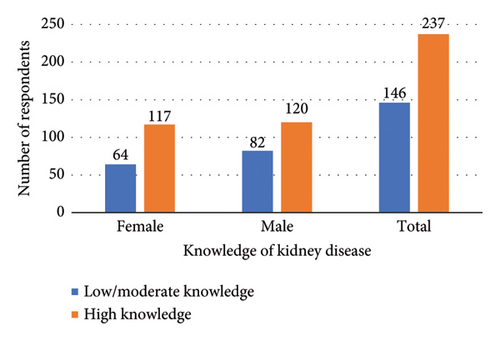

The majority of study participants had high knowledge (61.9% (237/383)). Nearly 65% of females and 59% of males had high knowledge (Figure 1).

The overall average knowledge score of respondents was 20.86 ± 3.88 out of a maximum score of 27 (77.26%) (Table 2). High knowledge level was observed for types and stages, diagnosis, and associated risk factors for KD (76.8% (3.84/5), 75.3% (5.27/7), and 81.6% (8.98/11), respectively) while moderate knowledge level was observed for signs and symptoms (69.3% (2.77/4)) (Table 2).

| Questions | Answers | Responses (N) | Frequency (%) | Mean knowledge score ± SD (maximum score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall knowledge of kidney disease | 20.86 ± 3.88 (27.00) | |||

| Types and stages of kidney diseases | 3.84 ± 1.22 (5.00) | |||

| Kidney diseases are mainly classified as | Severe, moderate, or mild | 36 | 9.4 | |

| Acute or chronic | 335 | 87.5 | ||

| Symptomatic or asymptomatic | 12 | 3.1 | ||

| Reversible traumatic kidney injuries can best be described as what type of kidney disease | Mild | 86 | 22.5 | |

| Symptomatic | 27 | 7.0 | ||

| Chronic | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Acute | 267 | 69.7 | ||

| Irreversible traumatic kidney injuries can best be described as what type of kidney disease | Severe | 75 | 19.6 | |

| Asymptomatic | 5 | 1.3 | ||

| Chronic | 301 | 78.6 | ||

| Acute | 2 | 0.5 | ||

| Mild kidney damage where the kidney works as normal is characterized by | Stage 1 kidney disease | 288 | 75.2 | |

| Stage 2 kidney disease | 62 | 16.2 | ||

| Stage 3 kidney disease | 12 | 3.1 | ||

| Stage 4 kidney disease | 7 | 1.8 | ||

| Stage 5 kidney disease | 14 | 3.7 | ||

| Stage 5 kidney disease is usually associated with itching and hyperuremia | Yes | 279 | 72.8 | |

| No | 104 | 27.2 | ||

| Signs and symptoms of kidney diseases | 2.77 ± 0.83 (4.00) | |||

| Abdominal pains and urination difficulty can be considered as early signs of kidney disease | Yes | 331 | 86.4 | |

| No | 52 | 13.6 | ||

| Fatigue is a major symptom of kidney diseases | Yes | 266 | 69.5 | |

| No | 117 | 30.5 | ||

| Advanced symptoms of kidney diseases include swelling of extremities and shortness of breath | Yes | 330 | 86.2 | |

| No | 53 | 13.8 | ||

| Consistently high blood pressure is a sign of a | Symptomatic kidney disease | 42 | 10.9 | |

| Acute kidney disease | 132 | 34.5 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 209 | 54.6 | ||

| Diagnosis of kidney diseases | 5.27 ± 1.47 (7.00) | |||

| eGFR is the best diagnosis marker for kidney disease patients | Yes | 314 | 82.0 | |

| No | 69 | 18.0 | ||

| Albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) may be used to detect the kidney diseases in patients. | Yes | 333 | 86.9 | |

| No | 50 | 13.1 | ||

| The following parameters will precisely help in diagnosing kidney disease of any type in patients | ||||

| Creatinine concentration | Yes | 265 | 69.2 | |

| No | 118 | 30.8 | ||

| Hemoglobin concentration | Yes | 124 | 32.4 | |

| No | 259 | 67.6 | ||

| Urine albumin concentration | Yes | 215 | 56.1 | |

| No | 168 | 43.9 | ||

| Blood urea and nitrogen concentration | Yes | 279 | 72.8 | |

| No | 104 | 27.2 | ||

| Renal function test may serve as a supporting investigation for diagnosing kidney diseases in patients | Yes | 354 | 92.4 | |

| No | 29 | 7.6 | ||

| Risk factors of kidney diseases | 8.98 ± 1.88 (11.00) | |||

| Much salt consumption causes kidney problem | Yes | 321 | 83.8 | |

| No | 62 | 16.2 | ||

| Drinking too much water can result in a kidney disease | Yes | 87 | 22.7 | |

| No | 269 | 77.3 | ||

| Drinking too little water can result in a kidney disease | Yes | 317 | 82.8 | |

| No | 66 | 17.2 | ||

| Smoking and alcoholism can result in a kidney disease | Yes | 357 | 93.2 | |

| No | 26 | 6.8 | ||

| Poorly managed hypertension and diabetes mellitus can result in a kidney disease | Yes | 360 | 94.0 | |

| No | 23 | 6.0 | ||

| Patients with HIV/AIDS are at risk of having a kidney impairment | Yes | 306 | 79.9 | |

| No | 77 | 20.1 | ||

| Patients infected with malaria and/or urinary tract infections are reasonably exposed to kidney diseases | Yes | 299 | 78.1 | |

| No | 84 | 21.9 | ||

| Can frequent usage of herbal medications cause kidney diseases? | Yes | 310 | 80.9 | |

| No | 73 | 19.1 | ||

| Persistent exposure to heat and agrochemicals can lead to a kidney disease | Yes | 289 | 75.5 | |

| No | 94 | 24.5 | ||

| Sickle cell disease patients are prone to kidney diseases due to dehydration? | Yes | 275 | 71.8 | |

| No | 108 | 28.2 | ||

| Frequent NSAID users are prone to kidney diseases | Yes | 311 | 81.2 | |

| No | 72 | 18.8 | ||

- Note: Bold values are the correct answer in each section, similar to how the responses and frequency have been bolded.

While 87.5% (335/383) of participants were able to identify correctly that KDs are mainly classified as acute and chronic, only 69.7% (267/383) and 78.6% (301/383) were able to identify that reversible and irreversible KD/damage may be classified as AKI and CKD, respectively (Table 2). The majority of participants were able to identify abdominal pains and urination as early signs of KD (86.4% (331/383)) and swelling of extremities and shortness of breath as advanced symptoms (86.2% (330/383)) (Table 2).

Majority of participants were also able to point out eGFR as a diagnostic marker for KD (82.0%), albumin to creatinine ratio usage to detect KD (86.9%), and renal function test as a supporting investigation for KDs (92.4%). However, 32.4% and 43.9% of participants failed to identify hemoglobin concentration as a nonparameter for precise diagnosis of KD and urine albumin concentration as a parameter that may help in KD diagnosis, respectively (Table 2).

The commonest risk factors identified by about 80% of participants were high salt consumption, insufficient water intake, HIV/AIDS, frequent herbal medication usage, and frequent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use (Table 2).

3.3. Factors Independently Associated With High Knowledge of KDs Among Participants

High knowledge about KD was observed among obese participants (100%), those reading medical laboratory science (81.1%), participants in the fourth year (72.4%), those who consume alcohol (80.0%), and participants with family history of chronic diseases (80.3%) (Table 3). Participants in their first year of study (36.8%), those studying health information management (20.8%), and those who smoke (0%) demonstrated the lowest levels of knowledge about KD (Table 3).

| Variables | No. (%) of respondents with high knowledge | cOR (95% CI) (univariable) | aOR (95% CI) (multivariable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | |||

| ≤ 20 | 54 (54.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 21–30 | 176 (64.2) | 1.50 (0.94–2.39) | 1.97 (0.84–4.66) |

| > 30 | 7 (70.0) | 1.94 (0.51–9.42) | 2.50 (0.14–43.69) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 117 (64.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Male | 120 (59.4) | 0.80 (0.53–1.21) | 0.78 (0.44–1.37) |

| Year of study | |||

| First | 21 (36.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second | 51 (68.0) | 3.64 ∗∗∗ (1.79–7.64) | 3.27 ∗ (1.22–9.02) |

| Third | 73 (58.9) | 2.45 ∗∗ (1.30–4.74) | 2.54 (0.99–6.71) |

| Fourth | 92 (72.4) | 4.51 ∗∗∗ (2.34–8.88) | 4.72 ∗∗ (1.63–14.37) |

| Program of study | |||

| Biomedical science | 22 (75.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Clinical nutrition and dietetics | 19 (48.7) | 0.30 ∗ (0.10–0.84) | 0.85 (0.20–3.61) |

| Health information management | 5 (20.8) | 0.08 ∗∗∗ (0.02–0.29) | 0.09 ∗∗ (0.02–0.39) |

| Medical imaging and sonography | 18 (36.0) | 0.18 ∗∗ (0.06–0.48) | 0.23 ∗ (0.06–0.82) |

| Medical laboratory science | 43 (81.1) | 1.37 (0.44–4.07) | 1.33 (0.36–4.66) |

| Optometry | 9 (50.0) | 0.32 (0.09–1.10) | 0.28 (0.06–1.21) |

| Physician assistance studies | 121 (71.2) | 0.79 (0.29–1.88) | 1.50 (0.42–5.02) |

| Possession of active health insurance | |||

| No | 40 (48.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 197 (65.4) | 1.99 ∗∗ (1.21–3.27) | 1.53 (0.84–2.81) |

| Smoking status | |||

| No | 237 (62.7) | — | — |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Intake of alcohol | |||

| No | 209 (60.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 28 (80.0) | 2.66 ∗ (1.19–6.77) | 5.96 ∗∗ (2.01–22.35) |

| Frequency of 30 min exercises per week | |||

| > 4 times | 30 (63.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 0–2 times | 159 (64.1) | 1.01 (0.52–1.92) | 0.95 (0.41–2.12) |

| 3–4 times | 48 (54.5) | 0.68 (0.32–1.40) | 0.68 (0.27–1.66) |

| Self-classification of lifestyle | |||

| Not stressful | 27 (49.1) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Relatively stressful | 156 (63.4) | 1.80 (1.00–3.25) | 1.01 (0.46–2.22) |

| Very stressful | 54 (65.9) | 2.00 (1.00–4.05) | 1.18 (0.46–3.00) |

| Family history of chronic disease | |||

| Don’t know | 19 (54.3) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| No | 169 (58.9) | 1.21 (0.59–2.44) | 1.38 (0.57–3.36) |

| Yes | 49 (80.3) | 3.44 ∗∗ (1.39–8.79) | 2.54 (0.82–8.09) |

| Self-description of body weight | |||

| Normal | 185 (58.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Obese | 3 (100.0) | 1477001.17 (0.00–NA) | 5003512.65 (0.00–NA) |

| Overweight | 26 (70.3) | 1.65 (0.81–3.59) | 1.89 (0.76–4.99) |

| Underweight | 23 (79.3) | 2.67 ∗ (1.12–7.40) | 3.93 ∗ (1.22–15.85) |

- Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; cOR, crude odds ratio; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

- p values are statistically significant at ∗(< 0.05), ∗∗(< 0.01), and ∗∗∗(< 0.001).

The univariate analysis showed that the year of study (second, third, and fourth), possession of valid health insurance, alcohol intake status, having a family history of chronic disease, and being underweight were significantly associated with high knowledge of KDs (Table 3). However, being in the second or fourth year, having alcohol intake status (OR = 5.96; 95% CI = 2.01–22.35; p = 0.003), and being underweight were significantly associated with high knowledge of KDs in the multivariate analysis. Participants in their second year of study had over three times higher odds of possessing high KD knowledge compared to first year students (OR = 3.27, 95% CI = 1.22–9.02, p = 0.020). The association was even stronger for fourth year students, who demonstrated nearly five times greater odds of high knowledge than first year undergraduates (OR = 4.72, 95% CI = 1.63–14.37, p = 0.005). Students reporting alcohol use had almost six times higher odds of high KD awareness compared to those who did not report alcohol intake (OR = 5.96, 95% CI = 2.01–22.35, p = 0.003).

4. Discussion

KDs are on the rise in developing countries and are linked to high rates of morbidity and death. In this study, we assessed the level of awareness and understanding of regular allied health sciences undergraduates regarding KDs and their risk factors.

In our study, the overall average knowledge score of KDs was found to be 20.86 ± 3.88 out of 27 (77.26%). This was higher than that observed in similar studies conducted in Ethiopia by Wolide et al. [14] and Northern Tanzania by Stanifer et al. [14, 16]. They found an overall knowledge score of 66.2% (8.6/13) and 32.8% (3.28/10), respectively [14, 16]. This variation could be due to the questionnaire used, study population, and sample size employed in various studies. The majority of participants (61.9%) in this study had a high level of knowledge about KDs, which might be due to the formal post-secondary education of study participants in the field of health. This affirms the findings of similar studies by Stanifer et al. [16] and Gheewala et al. [12, 16]. They found that those with post-secondary education knew more about KDs than people without or only with primary school education.

We also found a high knowledge level on the types and stages, diagnosis, and risk factors of KDs. In dissonance with our findings, Wolide et al. in 2019 observed that over half of their health student participants were able to identify symptoms and risk factors of KD with gaps in identifying laboratory diagnosis [14]. Further, we found a moderate knowledge level on the signs and symptoms of KDs, which might be due to the limited clinical exposure of the undergraduates. This finding further highlights some gaps in knowledge on the signs and symptoms as well as diagnosis of KDs among undergraduates reading health-related programs.

Ninety-four percent of participants were able to identify poorly managed diabetes mellitus and hypertension as risk factors for kidney diseases. However, a similar study by Roomizadeh et al. found that only 12.7% and 14.4% of study participants were able to identify poorly managed diabetes mellitus and hypertension as risk factors for CKD, respectively, in Iran’s general population. Kazley et al. also highlighted a deficiency in knowledge of KD risk factors among CKD patients in South Carolina, USA [13, 17]. Gheewala et al. [12] also found that 38.3% and 60.6% of participants correctly identified hypertension and diabetes mellitus as risk factors for CKD, respectively [12]. This indicates that the knowledge level of KDs in the general public is relatively lower compared to allied health students. This suggests that students enrolled in health-related programs should have a thorough understanding of all aspects of KDs, as this will enable them to better explain the condition to both their future patients and the general public, thereby increasing the knowledge of KD among the general public.

Among participants with active health insurance, a family history of chronic disease, and a history of alcohol consumption, high knowledge of KD was observed. Students reporting alcohol use had almost six times higher odds of high KD awareness compared to those who did not report alcohol intake (OR = 5.96, 95% CI = 2.01–22.35, p = 0.003). It is more likely that those with increased risk factors for KDs are more aware and concerned about kidney health issues. This could be due to the general idea that alcoholism in the long run causes KD as many participants in a similar study by Whitman et al. [18] identified alcohol misuse as the commonest cause of KD [18]. While alcohol misuse is a risk factor for KD, those reporting alcohol consumption may have gained knowledge through health warnings. Addiction could also impact drinking behaviors independent of understanding risks.

High knowledge of KDs among participants with a family history of chronic disease was similarly observed in Alobaidi et al.’s study in 2021 [19] and this could be attributed to these participants’ exposure to health education, awareness campaigns, and related health conditions, which fostered a higher knowledge environment about KDs during relatives’ health care. The reason for high knowledge among individuals with health insurance remains unclear, but it could possibly be due to the fact that having health insurance might facilitate access to medical care, resources, and knowledge about specific medical conditions.

Our study also revealed that participants reading health information management (20.8%) had the least number of respondents having high knowledge about KDs among the various disciplines of allied health. The curriculum for health information management program prioritizes teaching skills for processing, keeping, and managing health data. Aspects of health like disease diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, epidemiological patterns, and other fundamental medical topics may receive less emphasis. This could account for this observation.

In contrast to our study which found being in the second or fourth year, having alcohol intake status, and being underweight to be significantly associated with high knowledge of KDs in the multivariate analysis, Gheewala et al. [12] observed having a higher level of education, family history of kidney failure, a personal history of diabetes mellitus, and currently or previously living in a relationship to have significantly higher CKD knowledge scores [12]. The variations in results could be attributed to the study population and questionnaires employed in both studies. Additionally, underweight students could have pre-existing health issues prompting extra research into conditions.

The study may be limited by subject selection bias. We used random sampling methods where only voluntary subjects participated. Also, we were not able to compare our study with other studies in the region due to a lack of information in the area.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that allied health science undergraduates had adequate knowledge regarding KD and its risk factors. However, knowledge on the signs and symptoms of KDs was relatively low among participants. This shows the need to improve the current training of allied health undergraduates by integrating more content on KDs into their curriculum and providing them with more clinical exposure involving patients with KDs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

R.K.D.E., V.O.O., T.J.Y., M.A.E., and G.N.O. conceived and designed this study. V.O.O., T.J.Y., M.A.E., and T.A. were responsible for data collection. G.N.O. and M.A.E. were responsible for data analysis and visualization. R.K.D.E., T.A., and G.N.O. drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and agreed with the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their involvement in this study.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire Used in the Study

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |

| Age | |

| Gender | Male |

| Female | |

| Year of study | |

| Program of study | |

| Do you have an active health insurance? | Yes |

| No | |

| Do you smoke? | Yes |

| No | |

| Do you take alcohol? | Yes |

| No | |

| How many times do you exercise for 30 min in a week? | 0 to 2 times |

| 3 to 4 times | |

| More than or equal to 4 times | |

| How will you classify your lifestyle? | Very stressful |

| Relatively stressful | |

| Not stressful | |

| Do you have a history of kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia? | Yes or No |

| How will you describe your weight? | Normal |

| Obese | |

| Overweight | |

| Underweight | |

| Types and stages of kidney diseases | |

| Kidney diseases are mainly classified as | Severe, moderate, or mild |

| Acute or chronic | |

| Symptomatic or asymptomatic | |

| Reversible traumatic kidney injuries can best be described as what type of kidney disease | Mild |

| Symptomatic | |

| Chronic | |

| Acute | |

| Irreversible traumatic kidney injuries can best be described as what type of kidney disease | Severe |

| Asymptomatic | |

| Chronic | |

| Acute | |

| Mild kidney damage where the kidney works as normal is characterized by | Stage 1 kidney disease |

| Stage 2 kidney disease | |

| Stage 3 kidney disease | |

| Stage 4 kidney disease | |

| Stage 5 kidney disease | |

| Stage 5 kidney disease is usually associated with itching and hyperuremia | Yes |

| No | |

| Signs and symptoms of kidney diseases | |

| Abdominal pains and urination difficulty can be considered as early signs of kidney disease | Yes |

| No | |

| Fatigue is a major symptom of kidney diseases | Yes |

| No | |

| Advanced symptoms of kidney diseases include swelling of extremities and shortness of breath | Yes |

| No | |

| Consistently high blood pressure is a sign of a | Symptomatic kidney disease |

| Acute kidney disease | |

| Chronic kidney disease | |

| Diagnosis of kidney diseases | |

| eGFR is the best diagnosis marker for kidney disease patients | Yes |

| No | |

| Albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) may be used to detect the kidney diseases in patients. | Yes |

| No | |

| The following parameters will precisely help in diagnosing kidney disease of any type in patients | |

| Creatinine concentration | Yes |

| No | |

| Hemoglobin concentration | Yes |

| No | |

| Urine albumin concentration | Yes |

| No | |

| Blood urea and nitrogen concentration | Yes |

| No | |

| Renal function test may serve as a supporting investigation for diagnosing kidney diseases in patients | Yes |

| No | |

| Risk factors of kidney diseases | |

| Much salt consumption causes kidney problem. | Yes |

| No | |

| Drinking too much water can result in a kidney disease………. | Yes |

| No | |

| Drinking too little water can result in a kidney disease…….…. | Yes |

| No | |

| Smoking and alcoholism can result in a kidney disease……… | Yes |

| No | |

| Poorly managed hypertension and diabetes mellitus can result in a kidney disease……. | Yes |

| No | |

| Patients with HIV/AIDS are at risk of having a kidney impairment…………… | Yes |

| No | |

| Patients infected with malaria and/or urinary tract infections are reasonably exposed to kidney diseases………. | Yes |

| No | |

| Can frequent usage of herbal medications cause kidney diseases? | Yes |

| No | |

| Persistent exposure to heat and agrochemicals can lead to a kidney disease……… | Yes |

| No | |

| Sickle cell disease patients are prone to kidney diseases due to dehydration? | Yes |

| No | |

| Frequent NSAID users are prone to kidney diseases | Yes |

| No | |

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.