A Case Series of Adult and Pediatric Basidiobolomycosis in Saudi Arabia: An Emerging Rare Disease

Abstract

Background: Basidiobolomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Basidiobolus ranarum. It is primarily located in the tropical areas. It is commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract and rarely presents with systemic affection.

Patients and Methods: The records of fifteen patients, including pediatrics, from various geographic regions (western and southern regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) who were diagnosed with basidiobolomycosis in two tertiary hospitals over the last fourteen consecutive years from January 2010 to February 2023 were included. A detailed history and data for each patient were reviewed and evaluated.

Results: A total of fifteen patients were found to have basidiobolomycosis, of which fourteen were found to have gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB). They presented with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of weight. One of them with an orbital infection presented with periorbital swelling, hotness, and redness. The diagnosis was confirmed after histopathological examination with typical features of granulomatous reaction, dense infiltrate of eosinophils, and fungal structures. Seven patients were treated with antifungals alone, such as voriconazole or itraconazole. Eight patients were treated by surgical resection followed by antifungal medication. Ten patients demonstrated good clinical response and completed their treatment course, while one patient showed a slight improvement and is still receiving treatment and follow-up. There have been four reported cases of death. The length of the therapy was scheduled based on how the patients responded clinically to the intervention.

Conclusions: We present the series with the most patients collected to date, and it is shown that GIB is often misdiagnosed as cancer or inflammatory bowel disease. Histological analysis confirms the diagnosis of basidiobolomycosis. The choice of therapy is still up for debate: medical intervention alone or surgical resection followed by antifungal medication.

1. Introduction

Basidiobolomycosis is a rare, uncommon, and invasive fungal disease associated with high mortality. It is distributed worldwide, but tropical areas are the most commonly involved such as Africa, the USA, and Southeast Asia. Unlike other fungal infections, it affects immunocompetent patients. Many reported cases were from Saudi Arabia, mainly found in the southern region. Most cases were under 20 years of age [1]. One member of the Zygomycetes family, Basidiobolus ranarum, is the causative agent of basidiobolomycosisIt is found in animals such as fish, frogs, bats, and reptiles [2]. Basidiobolus ranarum has a four-day incubation period [3]. It is a member of the phylum Entomophthoromycota, which also contains one of the largest groups of early-diverging terrestrial fungi that were previously categorized in the phylum Zygomycota [4]. Basidiobolomycosis is typically a subcutaneous infection that primarily affects young, male individuals and is spread by traumatic inoculation. It affects the gastrointestinal tract as well. The transmission of this organism to humans is not well understood, and there are three major routes of infection: skin penetration after injury to an infected source, ingestion of contaminated food, and inhalation of an infected agent. The first reported case was in 1956 in Indonesia, when the patient presented with a subcutaneous basidiobolomycosis infection [5]. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is considered the most common presentation in tropical and subtropical areas.

Diagnosis of basidiobolomycosis is challenging because the clinical signs do not lead directly to fungal infection and due to nonspecific presentation of the disease and similarity with some malignant cases as well as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [6], which necessitate a high index of suspicion to reach the diagnosis. The most commonly affected abdominal organs are the colon (84%), the small intestine (32%), the liver (21%), and rarely other organs such as the stomach [7].

To confirm the disease, diagnostic workup is needed, such as radiological examinations and histological findings of a positive culture of Basidiobolus ranarum, which is considered the pathognomonic feature. This is one of the reported case series of GIB, including adult and pediatric, from Saudi Arabia. There has been one case series study aimed at describing five pediatric patients with basidiobolomycosis. In this case series study, we are describing the different clinical characteristics of the fifteen patients as well as the therapeutic plan and the outcome.

2. Method

This retrospective case series study was carried out at King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital (KFAFH) and King Abdulaziz Hospital and Oncology Center (KAHOC), both tertiary hospitals in Saudi Arabia. We used the microbiological and histopathological databases to identify basidiobolomycosis species from January 2010 to February 2023. The information of adult and pediatric patients who were diagnosed with basidiobolomycosis was collected. Our patients came from different cities in Saudi Arabia such as Jeddah, Al-Qunfudhah, and Abha, which are located at western and southern areas of Saudi Arabia (Tables 1 and 2). It is noticeable that fifteen patients’ records were collected, reviewed, and evaluated, and it was found that they had received empirical antibiotics initially until clinical workup and diagnosis became available. The empirical antimicrobial treatments administered ranged from a combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole to a carbapenem (Table 3). The most commonly used antifungals for adjusted therapy were voriconazole and itraconazole. Voriconazole was used in the vast majority of our patients, and it was obtained in adults as 6 mg/kg intravenously twice daily on the first day, followed by 4 mg/kg twice daily as long as the patient had normal kidney function, then switched to an oral regimen of 400 mg twice daily on the first day, followed by 200 mg twice daily if the patient tolerated it. The recommended voriconazole dose administered to pediatric patients (cases 11, 12, and 13) was according to the body weight, and it was given as an intravenous loading dose of 9 mg/kg, followed by maintenance doses of 8 mg/kg according to kidney function, or as an oral dose of 9 mg/kg if tolerated. In cases 8 and 15, the patients developed hallucinations and visual disturbance on Day 3 of the voriconazole treatment, so the dose was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, but still the symptoms persisted, so the treatment was changed to oral itraconazole. Itraconazole was used in five adult patients, and it was given as an oral dose of 200 mg twice daily, as seen in cases 3, 4, 5, 7, and 15. One pediatric patient with orbital manifestation developed allergic fungal sinusitis and lacrimal duct obstruction, which was initially treated with empirical liposomal amphotericin. The antifungal was then changed to oral voriconazole and continued for three years. The duration of therapy was planned according to patients’ clinical response toward the treatment, which includes the disappearance of clinical and radiological symptoms associated with the infection.

| Total number of patients (n) | 15 |

| Age (y) | 27.4 (1–70) |

| Male (n) % | (12) 80 |

| Female (n) % | (3) 20 |

| Adult (n) % | (11) 73.3 |

| Pediatric (n) % | (4) 26.6 |

| No. | Age (years)/gender | Clinical presentation | Diagnostic measures | Colonoscopy (−/+/ND) | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70/M | Right upper abdominal pain with anorexia | CT abdomen, colonoscopy, US-guided liver biopsy | Negative (not conclusive) | GI |

| 2 | 69/M | Abdominal pain, constipation, loss of appetite, and weight loss | CT abdomen, colonoscopy | Positive | GI |

| 3 | 44/M | Abdominal pain and diarrhea, associated with weight loss | CT abdomen, colonoscopy, US-guided liver biopsy | Positive | GI |

| 4 | 41/F | Diffuse abdominal pain, weight loss, bloody diarrhea, anorexia | CT abdomen, colonoscopy | Negative (not conclusive) | GI |

| 5 | 34/F | Abdominal pain, vomiting, weight loss, fever | CT abdomen, upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, lap omental nodule biopsy | Negative (not conclusive) | GI |

| 6 | 32/M | Acute abdominal pain, nausea, and anorexia | CT abdomen, colonoscopy | Negative (not conclusive) | GI |

| 7 | 22/M | Diffuse abdominal pain, weight loss | CT abdomen, US-guided aspiration, colonoscopy | Positive | GI |

| 8 | 20/M | Abdominal mass, watery diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and loss of weight | CT abdomen, lap mesenteric LN biopsy | ND | GI |

| 9 | 21/M | Abdominal pain, vomiting | CT abdomen | ND | GI |

| 10 | 9/M | Abdominal pain, vomiting, and weight loss | CT abdomen, US-guided biopsy | ND | GI |

| 11 | 6/M | Abdominal pain and vomiting | CT abdomen, colonoscopy, US-guided biopsy | Negative (not conclusive) | GI |

| 12 | 2/F | Left eye pain, swelling of the lids, and preseptal hotness and redness | CT scan, MRI, CT-guided biopsy | ND | Orbital sinonasal |

| 13 | 1/M | Abdominal distension, fever | CT abdomen, US-guided biopsy | ND | GI |

| 14 | 22/M | RUQ abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice | CT abdomen, colonoscopy, MRCP, ERCP | Positive | GI |

| 15 | 67/M | Abdominal pain, abdominal distention, vomiting, constipation, weight loss | Abdominal X-ray | ND | GI |

- Note: PO, oral.

- Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ERHC, extended right hemicolectomy; GI, gastrointestinal; LHC, left hemicolectomy; LN, lymph node; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; ND, not done; RHC, right hemicolectomy; US, ultrasound.

| Patients | Age (years)/gender | Empirical therapy | Medication therapy alone | Surgical intervention | Complications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70/M | IV meropenem | Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 2 months then lost f/u | None | None | Improved |

| 2 | 69/M |

|

Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 1 year | Extended right hemicolectomy | Psychosis | Improved |

| 3 | 44/M |

|

Itraconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 1 year and 3 months | None | None | Improved |

| 4 | 41/F | No specific data | Itraconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 1 month | Extended right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis, sigmoid colostomy, Graham patch | None | Died |

| 5 | 34/F |

|

Itraconazole, 200 mg PO twice daily for 6 months | Laparoscopic exploration and omental nodule excisional biopsy | None | Died |

| 6 | 32/M |

|

Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily, 1 year | Left hemicolectomy with limited ileocecal resection and anastomosis | None | Improved |

| 7 | 22/M | IV imipenem | Itraconazole, 200 mg PO twice daily | RHC, rectosigmoid resection with end colostomy, debridement and necrosectomy of abdominal wall, urinary bladder repair, and ureteral repair | None | Died |

| 8 | 20/M | IV tigecycline, IV ciprofloxacin, IV metronidazole | Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily then 100 mg PO twice daily for 2 years and 2 months | Laparoscopic mesenteric LN biopsy | Psychosis | Improved |

| 9 | 21/M | IV imipenem | Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 1 month | Extended right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis, partial gastrectomy | None | Died |

| 10 | 9/M |

|

Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 2 years | None | None | Improved |

| 11 | 6/M | No specific data | Voriconazole 100 mg twice daily PO for 1 year | None | None | Improved |

| 12 | 2/F | IV ceftriaxone | Liposomal amphotericine intravenously then continued on oral voriconazole | Maxillectomy and orbital decompression | Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis and lacrimal duct obstruction | Improved |

| 13 | 1/M | IV ceftriaxone | Voriconazole 75 mg po q12 h, for 2 years | Transverse colectomy and fistula excision | None | Improved |

| 14 | 22/M | IV meropenem | Voriconazole 200 mg PO twice daily for 8 months | None | None | Improved |

| 15 | 67/M | IV meropenem and metronidazole |

|

Subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy | Psychosis | Improved |

- Note: PO, oral.

- Abbreviations: F, female; IV, intravenous; LN, lymph node; M, male.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

The mean age of the study patients at presentation was 27.4 years (range, 1–70 years). Fourteen patients (93.3%) presented with GIB, while one patient (6.6%) presented with ocular basidiobolomycosis. Twelve patients (80%) were medically free, with the exception of three who had hypertension and diabetes mellitus, one of whom only had diabetes mellitus (20%). All patients who were reported to have GIB had chronic abdominal pain as their main symptom. It was associated with nausea (n = 3), vomiting (n = 6), anorexia (n = 3), changes in bowel habits, bloody diarrhea (n = 1), fever, and unintentional weight loss. On physical examination, intra-abdominal distention or palpable masses had been detected in seven patients. One of the GIB cases presented with typical symptoms and signs of obstructive jaundice. One patient presented with eye pain, swelling of the eye lids, redness, periorbital hotness, and a slight decrease in visual acuity and was diagnosed with orbital basidiobolomycosis (Table 2).

3.2. Laboratory Findings

All study patients had raised white blood cell counts ranging from 13 to 33 cells × 109/L (median 14.2 cells × 109/L) except one and the majority had thrombocytosis, with the exception of three who demonstrated a normal platelet level and a lack of data for one. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were elevated in most patients, with a lack of data for two patients. Eosinophil levels were also high in all patients except one, with one patient having more than 10 cells × 109/L, which was 28 cells × 109/L. The majority of patients had low hemoglobin levels, with the exception of two who were normal. In every patient’s study, kidney function biomarkers showed normal values except one. One patient had elevated liver function tests, while it varies from patient to patient in others; for example, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was high in 66.6% (n = 10 patients), and total bilirubin was raised in 20% (n = three patients) (Table 4).

| Age (years)/gender | White blood cells (WBCs) (× 109/L) | C-reactive protein (CRP) μmol/L | Platelets (× 109/L) | Eosinophil (× 109 cells/L) | Hemoglobin g/dL Male: 13.8–17.2 (g/dL), female: 12.1–15.1 (g/dL) |

Serum creatinine (Umole/L) (64–111 U mole) |

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (50–116U/L) |

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (7–55U/L) |

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (8–84)U/L |

Total bilirubin (2-21 Umol/L) | Comorbidities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 70/M | 18.5H | 356H | 716H | 3.8 | 9.4 | 98 | 200H | 6 | 39 | 96H | DM/HTN |

| Patient 2 | 69/M | 13H | 286H | 260 | 1.7 | 9.5 | 68 | 73 | 13 | 17 | 5 | MF |

| Patient 3 | 44/M | 14.2H | 219H | 372 | 3.9 | 14.7 | 67 | 112 | 19 | 16 | 6.4 | DM |

| Patient 4 | 41/F | 8.6 | 85H | 656H | 1.2 | 9.8 | 35 | 91 | 8 | 12 | 4.2 | MF |

| Patient 5 | 34/F | 25H | 191H | 454H | 0.56 | 9.6 | 45 | 122 | 97H | 17 | 5.3 | MF |

| Patient 6 | 32/M | 14H | 30H | 323 | 2.88 | 16 | 65 | 81 | 31 | 21 | 10 | |

| Patient 7 | 22/M | 33H | 265H | 831H | 3.4 | 9 | 224H | 218H | 20 | 37 | 18.5 | MF |

| Patient 8 | 20/M | 13.7H | 270H | 598H | 1.9 | 12.8 | 68 | 107 | 8 | 44 | 17 | MF |

| Patient 9 | 21/M | 13.5H | 222H | ND | 8.99 | 9.8 | 43 | 185H | 12 | 11 | 25H | MF |

| Patient 10 | 9/M | 18.5H | 270H | 740H | 3.8 | 9.8 | 54 | 244H | 10 | ND | 4 | MF |

| Patient 11 | 6/M | 33H | 85H | 873H | 0.33 | 7.6 | 52 | 289H | 57 | ND | 10.5 | MF |

| Patient 12 | 2/F | 13.8H | 99H | 772H | 0.9 | 10.2 | 20 | 220H | 13 | ND | 2.5 | MF |

| Patient 13 | 1/M | 27H | 229H | 734H | 28 | 6.9 | 12 | 296H | 44 | ND | 4.4 | MF |

| Patient 14 | 22/M | 13.9H | ND | 413H | 1.7 | 13.5 | 66 | 254H | 333H | 202H | 88H | MF |

| Patient 15 | 67/M | 23.9H | ND | 413H | 1.7 | 9.5 | 50 | 220H | 58 | 44 | 21 | DM/HTN |

- Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; H, high; HTN, hypertension; MF, medically free; ND, not done.

3.3. Radiology Findings

The diagnostic workup used in the investigation differed. Abdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) were required according to the clinical presentation. A CT scan was the main diagnostic tool in fourteen patients. It confirmed the site of organ involvement and the extent of disease infiltration. A CT-guided tissue biopsy (core needle biopsy) was also essential for diagnosis in those cases that failed to obtain an adequate tissue biopsy through colonoscopy. The common finding seen in an abdominal CT scan was the presence of colonic intraluminal fungating mass with severe thickening of the bowel wall and luminal narrowing, as well as local infiltration to adjacent organs, associated with diffuse mesenteric fat stranding and engorged vessels. These findings in the CT scan make the differentiation between basidiobolomycosis and malignancy so challenging (Figure 1). One patient (case no. 14) presented with obstructive jaundice and required further investigation by MRCP and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). ERCP was repeated twice but failed to intubate the ampulla of Vater due to severe outside compression, so PTC was the only way to drain the biliary system through an external and internal drain.

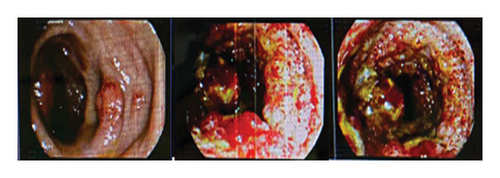

3.4. Colonoscopy Findings

Colonoscopy was done for nine cases who presented with gastrointestinal involvement. It showed severely inflamed mucosa with extensive widespread cobblestone-like lesions easily bleeding on touch with intraluminal narrowing mimicking IBD and/or malignancy (Figure 2, case no. 2). The biopsies were taken and were positive for basidiobolomycosis in four cases only.

3.5. Histopathology Findings

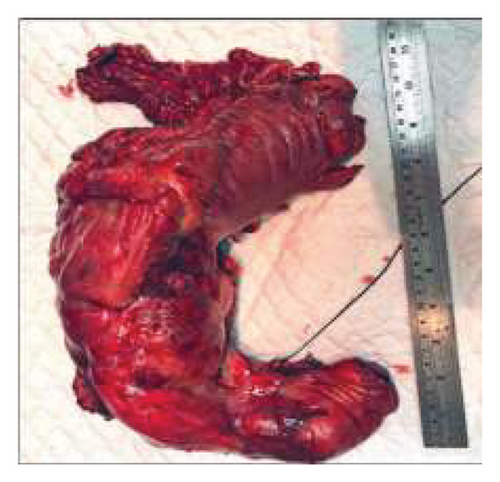

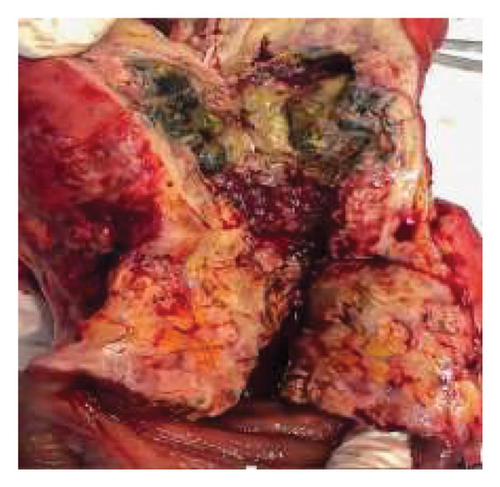

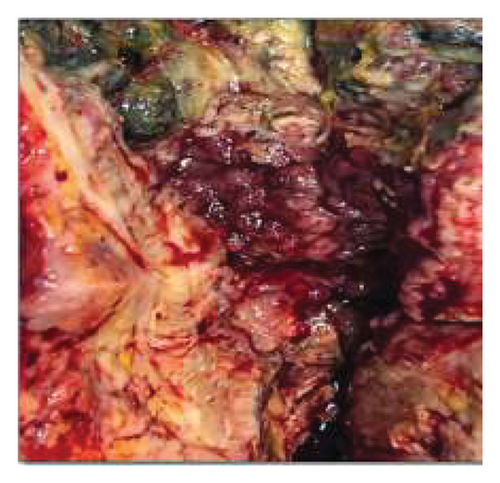

A tissue biopsy to confirm the diagnosis was obtained through either colonoscopy, interventional radiology (IR) using CT or US guidance, or surgical intervention. Nine patients underwent colonoscopy, and the biopsy was positive in only four cases. IR-guided biopsy confirmed the diagnosis in six cases; one case had CT-guided, while five had US-guided tissue biopsy (cases 1, 3, 10, 11, and 13). US-guided aspiration has been used in one patient, and it was not helpful because it failed to get enough fluid (case no. 7). Two patients had laparoscopic exploration with omental nodule excision (case no. 5) and lymph node biopsy (case no. 8), where the diagnosis was confirmed. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis for the patient who underwent surgical resection, as shown in eight cases (cases 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13, and 15). Figures 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c) show the gross appearance of the resected specimen in case no. 2 who had extended right hemicolectomy. The specimen showed a large fungating mass adherent to the surrounding tissue, with fat infiltrating mimicking adenocarcinoma. The cut surface of the specimen showed a cobblestone appearance mimicking Crohn’s disease (Table 2).

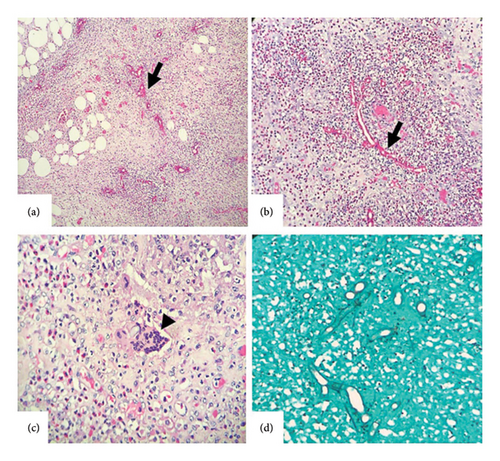

The microscopic examination of the specimen showed the fungal elements, which often appear as blank spaces, surrounded by a highly pigmented eosinophil. There was an abundant eosinophilic-rich transmutable inflammation admixed with neutrophils and a chronic granulomatous reaction with giant cells. The enormous cells, which are encircled by brilliantly eosinophilic amorphous detritus in a starburst pattern known as the “Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon,” exhibit a broad, pauci-septate fungal hyphae. The fungal organism tests positive for Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) (Figures 4(a), 4(b), 4(c), and 4(d)).

4. Treatment Course and Outcome

All fifteen patients were treated either by surgical resection followed by antifungal therapy or by antifungal treatment alone. Ten cases (66.6%) underwent surgical intervention, and two (13.3%) had laparoscopic exploration and tissue biopsy only, while eight cases (53.3%) required surgical exploration and radical resection because of their acute presentation (Appendix 1) (cases 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13 and 15). Four patients (26.6%) underwent right hemicolectomy; one patient had left hemicolectomy with limited ileocecal resection and anastomosis (case no. 6); one patient (6.6%) had subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy (case no. 15); one patient (6.6%) had transverse colectomy and enterocutaneous fistula excision (case no. 13); and the pediatric patient with orbital involvement had maxillectomy and orbital decompression (case no. 12) (Table 2). Ten patients (66.6%) showed good clinical response, and they finished their treatment course; only one case showed mild improvement and is still under treatment and follow-up.

Death has been reported in four cases (26.6%), three of them underwent surgery followed by itraconazole therapy, and one case was treated with voriconazole alone without surgery (Appendix 1) (cases 4, 5, 7, and 9). In case no. 4, the exact cause of death was uncertain, but we suspected that major cardiomyopathy and pulmonary hypertension were the probable cause of death. In case no. 5, the patient was started on itraconazole after laparoscopic exploration and omental nodule excisional biopsy. She was seen in the first visit after two months and showed a good clinical response, but she lost her follow-up. After calling the family, we have been informed that she died after six months from the diagnosis with no clear answer about the cause of her death. In case no. 7 (Appendix 1), the patient underwent extensive prolonged surgical procedure that included right hemicolectomy, rectosigmoid resection with end colostomy, debridement associated necrosectomy of abdominal wall, and urinary bladder repair with ureteric repair. Due to his critical condition, the patient was admitted to the critical care unit, where he passed away on the second day following surgery. In case no. 9 (Appendix 1), the patient underwent exploration laparotomy with partial gastrectomy and extended right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis. The patient did well and was discharged home after clinical improvement. Ten days from discharge, he reported to the emergency room complaining of a cough and fever with a wound infection; COVID-19 swap was positive; he was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), intubated, and ventilated; he developed respiratory failure and died with a COVID-19-related complication (Table 3).

5. Discussion

Gastrointestinal infections have been reported to affect immunocompetent hosts [8]. The southern region of Saudi Arabia has reported the highest number of cases of B. ranarum infection, which grows more quickly in warm, humid climates like those found in the southern region of Saudi Arabia, Arizona, West Africa, and Indonesia [9]. Most of the recorded reports showed that the young male age group was the most affected by basidiobolomycosis [10]. Our current data revealed the same results in addition to pediatrics.

Nonspecific symptoms are seen in the presentation of GIB. Abdominal pain, constipation, abdominal mass, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are among the most typical symptoms of GIB [2, 11]. The lack of specificity in the symptoms could cause a delay in diagnosis and raise the patient’s risk of morbidity [11]. While the primary diagnostic method at the moment is the histopathological analysis of biopsy specimens, there are additional methods as well; these include molecular methods, fungal cultures, and serological testing, which, when available, can definitively determine the diagnosis [12]. Histopathology may reveal a dense eosinophilic reaction encircling thin-walled, irregularly branching hyphae with sporadic septate (Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon) as seen in our cases (Appendix 1) [13, 14].

Eosinophilia in the peripheral blood can be a helpful adjunct to diagnosis [15]. The majority of study patients had elevated WBC counts, eosinophils, and CRP and low hemoglobin. The radiological examination varies according to the affected organ. CT is the most common radiological method used in investigation. The most common radiological findings are colonic masses, liver lesions, and involvement of the small intestine; less commonly affected are the gallbladder, kidneys, pancreas, and retroperitoneum [2]. Life-threatening consequences such as gastrointestinal perforation, intra-abdominal collections, obstruction, esophageal varices, duodenal-biliary fistula, and nephritis have been reported [16]. Bowel obstruction is the most common complication in most of our cases.

The treatment of choice for basidiobolomycosis remains a matter of debate [2]. The previously preferred treatment was the combination of surgical excision of affected organs followed by long-acting antifungal medication [17]. Vikram et al. showed that itraconazole and voriconazole were the most efficient therapies in most cases, and for those with obstructive symptoms or perforation, surgical intervention is indicated. Nevertheless, there has been a recent shift toward treating the patient with antifungal drugs alone, particularly with antifungals from the azole group [7]. Patients who had pre-existing risk factors like cardiac diseases were likely more susceptible to itraconazole’s harmful side effects on the heart since it was reported to produce impairment in cardiac function [18]. In any case, whether surgery is performed or not, a long-term antifungal treatment is recommended [13]. Without surgery, medical treatment for six to twelve months has been demonstrated to have positive effects in both adults and pediatric patients [2]. Thus, depending on the patient’s critical condition and response to medication, surgery may not be necessary [2]. In this series, the shortest period of antifungal therapy was 6 months, while the longest course was 26 months (the third patient) (Table 3). Since there is no prior local experience with the disease and it is uncommon, different medications were chosen with no clear indication of which was superior to the other. However, in any case, regular follow-up with periodic liver and renal functions is required, as was done in this series. Therefore, surgery may be avoided, depending on the patient’s critical condition and response to medications [2]. In our case series, azole-based antifungal demonstrated a beneficial effect in treating basidiobolomycosis with a low risk of complications. Surgical intervention was required in eight patients due to their acute critical presentation followed by antifungal treatment with a good response. GIB is considered a life-threatening condition if a delay in management occurs. Hence, high index of suspicion such as abdominal masses with early diagnosis, aggressive medical therapy, and surgical resection are considered the critical components of management. A mortality rate of 16% had been reported if not managed properly [11]. Pandit et al. reported that patients who undergo surgical resection without antifungal treatment have a high mortality rate [19]. In our case series, the mortality rate related to basidiobolomycosis was one out of fifteen.

6. Conclusion

In this report, we introduced the fifteen cases of basidiobolomycosis as a rare, invasive, and life-threatening disease that affects immunocompetent patients. A prompt and accurate diagnosis is needed to avoid fatal complications. Since its diagnosis is difficult, the presence of an abdominal mass associated with high eosinophilia should raise suspicion of GIB. Long-term azole antifungal therapy was effective in curing this illness and had shown to be a component of the treatment; nevertheless, in certain conditions, surgery is still required in conjunction with other treatments.

Ethics Statement

There is no identifiable information on the patients.

Consent

The data for the patients were obtained from the hospital’s electronic system.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No financial funding was received for this work.

Supporting Information

Appendix 1 contains detailed documentation of fifteen medical conditions that form part of a comprehensive case series. Each case provides insights into specific clinical presentations, treatment approaches, and outcomes, contributing to a broader understanding of the conditions being studied. This appendix serves as a good resource for clinicians and researchers, offering a rich dataset for treatment efficacy and patient outcomes in the specific clinical context addressed in the case series.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available and included in the article/supporting material/referenced article.