Association of Telemedicine With Life Satisfaction and Satisfaction With Care in Rural China

Abstract

Objectives: The effectiveness of telemedicine in rural areas with low-quality primary care remains unclear. This study examined the relationship of telemedicine adoption with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care in rural China. It also investigated the association of telemedicine with health-seeking behaviour, healthcare utilisation and heterogeneity in the type of telemedicine collaboration and the quality of healthcare workforce.

Methods: Data were retrieved from the China Livelihood Survey, a nationally representative multi-level survey conducted in 2021. Ordinary least-squares regression models were employed to analyse the relationship between telemedicine adoption at the village level and rural households’ life satisfaction and satisfaction with healthcare. Propensity score matching was used to address the potential selection bias.

Results: A total of 4638 households were included in the analysis. The results show that telemedicine adoption in village clinics was associated with higher levels of life satisfaction and satisfaction with healthcare among rural households. This improvement was primarily attributed to an increased likelihood of seeking care at primary care facilities, rather than a reduction in healthcare expenditures. The association was stronger when village clinics collaborated with township health centres in telemedicine initiatives, compared to those partnering with higher-level hospitals. Moreover, the association was more pronounced in villages with lower-quality healthcare workers compared to those with higher-quality staff.

Conclusion: These findings highlight telemedicine as an effective tool for improving rural residents’ satisfaction. Strategies such as promoting strengthened telemedicine collaboration at local levels and targeting telemedicine resources to remote areas with deficient primary care workforces are recommended to optimise telemedicine adoption in primary care in China and other developing countries.

1. Introduction

Telemedicine has emerged globally as a transformative solution to enhance satisfaction, reduce health disparities and improve access to high-quality care at a lower cost for populations with limited healthcare access [1, 2]. In China, the government has identified telemedicine as a key strategy to address healthcare inequities and strengthen primary care services in underserved and impoverished areas [3]. To this end, a pilot project under the national e-Health strategy was initiated in 2018 to equip rural primary facilities with telemedicine capabilities and promote collaborations with higher-level healthcare institutions. As of the end of 2021, telemedicine coverage had expanded significantly, exceeding 90% at the county level nationwide and reaching approximately 70% at the township level in pilot rural areas [4].

Despite China’s significant strides in adopting telemedicine, a fundamental issue that remains unanswered is the effectiveness of these initiatives in improving satisfaction, particularly in rural areas where healthcare disparities persist and the quality of primary care remains low [5, 6]. International research and practices have highlighted the promise of telemedicine in addressing primary care challenges, particularly in rural communities [7–9]. However, most studies on the effects of telemedicine have been conducted in developed countries, primarily due to the difficulties in implementing telemedicine in primary care settings in developing countries [10].

China, as a developing country, faces disparities in medical resources and healthcare utilisation between urban and rural areas [11]. In rural China, village clinics, at the bottom tier of a three-tiered hierarchy, offer grassroots primary care and public services together with township health centres [12]. However, long-standing gaps in resource allocation and workforce quality have created substantial challenges in delivering high-quality primary care in these areas [13]. These disparities, combined with geographic and economic barriers, make rural areas a critical focus for evaluating telemedicine as a tool to address healthcare inequities. Evidence suggests that the quality of care in China’s rural clinics remains low. Specifically, the utilisation rate of health information technology system in village clinics is only about 60%, as village doctors either lack the knowledge to use it or find it convenient [5]. The inefficient delivery of new technology and resources may further impede the actual realisation of benefits for rural residents through telemedicine.

Previous research has predominantly focused on direct-to-customer applications and has generally shown high satisfaction and enhanced access to care with telemedicine for primary care [2, 14]. However, there, studies may suffer from self-selection bias, as older, poorer or less educated patients are less likely to use telemedicine for their care [15, 16]. To address this issue, an exogenous technological institutional setting can better identify the effects of telemedicine. Government-led initiatives aimed at promoting telemedicine from the top-down can help mitigate healthcare disparities by addressing the challenges of digital divide faced by socioeconomically disadvantaged patients or those residing in remote areas with poor Internet connectivity [17].

In addition to its influence on satisfaction, telemedicine may also influence patients’ choices of healthcare facilities by enhancing the quality of primary healthcare [18]. In China, the absence of a gatekeeping system allows rural patients to bypass primary care [12]. The declining utilisation of village clinics further compounds social costs and exacerbates healthcare resource imbalances [19]. Telemedicine, together with initiatives such as gradient reimbursement schemes and referral reforms [20], can serve as a tool for establishing a hierarchical medical system and steering residents toward primary healthcare facilities.

The association between telemedicine and spending remains ambiguous. While some studies have indicated that telemedicine reduces spending by enhancing access to care [14, 21], village clinics in China, operating as for-profit entities, are likely to increase follow-up appointments, testing or prescriptions following the adoption of telemedicine. Coupled with the heightened demand for healthcare services facilitated by the convenience of telemedicine, this may pose challenges in reducing healthcare spending [22].

Highlighting the disparities in telemedicine collaboration types and workforce quality is crucial. Township health centres maintain a closer relationship with village clinics compared to county-level and higher hospitals, as they both form integral parts of the primary healthcare system. They are typically geographically proximate and share a common focus on primary care services and public health initiatives [12]. Moreover, workforce capacity has been identified as a pivotal factor for the effective delivery of telemedicine [23]. However, village doctors, compared to other primary healthcare practitioners with formal medical qualifications, tend to be less educated and qualified. The majority (84.3%) of village doctors have technical school education or over 20 years of practicing experience in village clinics, holding only a ‘Rural Physician’ certificate instead of a regular licence, which restricts their practice solely to village clinics [5, 6]. This issue of workforce quality contributes to low adherence to clinical checklists, suboptimal rates of correct diagnoses and treatments and limited coverage of basic clinical tests [24], thereby exacerbating patient distrust or dissatisfaction with the primary healthcare system [5].

This study is the first to provide both subjective and objective evidence on the effectiveness of telemedicine adoption in rural China. We employ an analysis guided by the Andersen behavioural model (ABM) of healthcare outcomes [25] to categorise telemedicine as a component of the healthcare system—an environmental factor influencing satisfaction as a key healthcare outcome. We then use a cross-sectional, nationally representative multi-level survey to analyse the association of telemedicine (and its different collaboration types) with life satisfaction, satisfaction with healthcare, health-seeking behaviours and healthcare utilisation among local rural households. We employ propensity score matching (PSM) to address the endogeneity resulting from village-level selection. Furthermore, we explore whether the association between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care varies across different types of telemedicine collaboration and the quality of village doctors.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

The data used in this study were derived from the China Livelihood Survey conducted by the Development Research Center of the State Council and the National Bureau of Statistics. This survey aims to reflect the health and livelihood status of residents through surveys of a representative sample. Conducted annually since 2013, each wave comprises approximately 11,000 households across 90 counties and districts in 9 provinces of China. Sampling for these data followed a multistage stratified random sampling approach. In the first stage, nine provinces were selected as the representative provinces from the eastern, central and western areas of China. In the second stage, a total of 40 communities or villages were selected as survey units in each province using probability proportional to size sampling. In the third stage, 25 households were randomly selected in each survey unit, and the adult with a birthday closest to 1 October was selected as the respondent among the adult population aged between 18 and 80 years old in each interviewed household. The survey samples were roughly similar to the sociodemographic characteristics observed in other national-level datasets (see Table S1).

The current analysis utilised data from the newly released 2021 cross-sectional survey, which includes both household and village surveys. The household survey collected a range of household-level information on socioeconomic status, health status, healthcare utilisation and expenditures, and life and service satisfaction. These household survey data are especially important since they collect, for example, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics that are not available in administrative data, as well as information about household members’ behaviour and expenditure that is not available in individual survey data. The village survey collects information on village characteristics such as population, economy, facilities, resources and services. The initial sample consisted of 5246 rural households. We excluded approximately 10% of households due to missing information on outcomes or because they answered ‘don’t know’ to the questions regarding satisfaction with care. We also excluded households with incorrect medical expense records. Our final analytic sample included 4638 households with complete information on all outcomes and covariates. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the final analytic sample were comparable to those in the excluded subset, except that excluded respondents were less likely to be female and with a lower proportion of household healthcare needs (see Table S2).

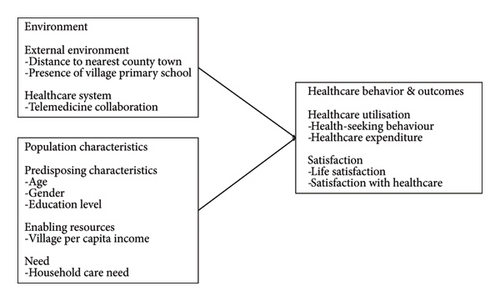

2.2. Conceptual Framework

We developed our conceptual framework guided by the ABM to analyse the multilevel determinants of healthcare outcomes associated with telemedicine in rural China, as illustrated in Figure 1. The ABM provides a structured approach to understanding how various factors influence health behaviours and outcomes, categorising them into five domains: external environment (e.g., village geographic and infrastructural characteristics), healthcare system (e.g., telemedicine), predisposing characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education level), enabling resources (e.g., income level) and need (e.g., household care need) [25, 26]. Using this framework, we explore the influence of these determinants on healthcare behaviour—such as health-seeking behaviour and healthcare expenditure—and outcomes, particularly satisfaction, with variables selected based on their potential associations with satisfaction, as informed by prior research [27, 28].

2.3. Dependent Variables

The key outcome variables are life satisfaction and satisfaction with healthcare. We measured life satisfaction using the self-rated life satisfaction item, which captured respondents’ overall satisfaction with their household living conditions on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

We measured satisfaction with healthcare by averaging two subjective indicators: perceived improvements in the accessibility of healthcare over the past 12 months and perceived improvements in the affordability of healthcare over the past 12 months, both rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (significantly worsened) to 5 (significantly improved). These three indicators are commonly used in the healthcare literature to measure both life satisfaction and specific satisfaction with the quality of care [21, 29, 30].

Another set of outcome variables pertains to healthcare-seeking behaviour. We operationalised this variable as the choice for healthcare facilities of rural residents. Respondents were asked about their preferred healthcare facility when they or their family members fall ill. The answer to this question reflects the residents’ health-seeking behaviour, specifically their choice among different levels of healthcare facilities [20]. We constructed a set of dummies to indicate whether the healthcare-seeking behaviour involves self-treatment, village clinics, township health centres, or county-level or above hospitals.

In addition, we used three measurements of healthcare utilisation: inpatient incidence, household inpatient expenditure and out-of-pocket household medical expenditure. We measured inpatient incidence with a binary indicator, denoting whether any family member had been hospitalised in the past year. To measure household inpatient expenditure, we inquired about the total sum respondents’ families had spent on hospitalisation in the past year. For situations where no family members had been hospitalised during this timeframe, the expenditure measurement takes the value of zero. Similarly, for out-of-pocket household medical expenditure, respondents were asked about the amount their total family spent on healthcare out-of-pocket in the past year. All expenditures displayed in the tables are presented in RMB or CNY, abbreviations for Chinese Yuan. In the text, we converted them to US dollars using an exchange rate of 1 USD to 7 CNY.

2.4. Independent Variables

We extracted data on telemedicine collaboration from the village survey. Based on available information, we constructed one binary variable that indicates whether households were from villages where village clinics had established telemedicine collaborations with higher-level health facilities, including township health centres or county-level and higher hospitals. The items were coded as 1 if there was such a collaboration at the village level. In our study sample, out of 388 villages surveyed in 2021, 63 had established telemedicine collaboration with higher-level heath facilities. Specifically, 50 villages had established telemedicine collaboration with township health centres, while 34 villages had established telemedicine collaboration with county-level or above hospitals.

2.5. Control Variables

We included individual and household characteristics as control variables, which encompassed the individual’s age (measured in years), gender (codec as 1 for female), education level (categorised as not educated, primary school, middle school, high school, or college or above) and having a household member in need of care due to illness, disability or ageing (coded as 1 if there is someone in the family with such a need). Furthermore, we incorporated several village-level characteristics as control variables to account for geographic conditions, economic development and education level of villages. These included the closest distance between the village office and county seat, the collective village income per capita and whether there was a primary school in the village.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We initially used linear regression models to estimate the relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care among rural residents. After estimating these main associations, we employed PSM to address potential sample selection bias in our multilevel regression results. Residents in villages with telemedicine collaboration were matched to those in villages without such collaboration based on estimated probability and propensity scores, using one-to-one matching, nearest neighbour matching within a calliper of 0.01 and kernel matching methods.

Next, we assessed covariate balance by examining the standardised difference (% bias) between the treatment and control groups. We used the threshold of 10% to determine whether covariate balance was achieved; specifically, matching was considered acceptable only when the standardised difference (% bias) was below this cut-off. Once the balance was satisfied, we proceeded to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) [31], which reflects the causal effects of telemedicine collaboration.

Additionally, we conducted further regression analyses to explore the mechanisms underlying these associations. We first estimated how telemedicine was associated with rural residents’ healthcare-seeking behaviour and healthcare utilisation. We then investigated whether the associations of telemedicine with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care varied based on the type of telemedicine collaboration and the quality of village doctors. All models were adjusted for individual, household and village characteristics to ensure robust results. To account for potential correlations in error terms within clusters, we clustered the error terms at the county level. All analyses were performed using Stata 16.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the analytic sample, comprising 4638 observations. The mean age is 53 years, with approximately 37% being female and 74% having middle school education or below. Within our sample, 21% of households have members requiring care due to factors such as illness, disability or aging. Rural respondents report an average life satisfaction score of 3.9 and a satisfaction with a healthcare score of 3.6. The probability of any household member’s hospitalisation in the past year is 29%, with average costs for hospitalisation and household out-of-pocket medical expenses at $968 and $594, respectively. Regarding healthcare-seeking behaviour, 11.2% of households opt for self-treatment, 36.5% choose to visit village clinics, 28.4% go to township health centres and 23.9% seek care at county- or higher-level hospitals. In terms of telemedicine collaboration at the village level, 37.2% of rural households reside in villages with established telemedicine collaborations, with 16.1%, 7.2% and 13.8% having collaborations with township health centres only, with county-level or higher hospitals and with both township health centre and higher-level providers, respectively.

| Number of observations (proportion)/mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |

| Life satisfaction | 3.914 (0.894) |

| Satisfaction with healthcare | 3.601 (0.787) |

| Household inpatient incidence (%) | 1356 (29.24%) |

| Total household inpatient expenditure | 6779 (29,241.46) |

| Out-of-pocket household medical expenditure | 4161 (10,063.75) |

| Healthcare-seeking behaviour (%) | |

| Self-treatment | 519 (11.2%) |

| Village clinics | 1693 (36.5%) |

| Township health centres | 1317 (28.4%) |

| County-level or above hospitals | 1109 (23.9%) |

| Independent variables | |

| Telemedicine collaboration (%) | 1717 (37.02%) |

| With THCs only | 747 (16.11%) |

| With county-level or above hospitals only | 332 (7.16%) |

| With both THCs and county-level or above hospitals | 638 (13.76%) |

| Individual and household characteristics | |

| Age in years | 53.17 (13.27) |

| Female (%) | 1715 (37%) |

| Education (%) | |

| Primary school | 1565 (33.75%) |

| Middle school | 1633 (35.22%) |

| High school | 563 (12.14%) |

| College or above | 316 (6.81%) |

| Having household members in need of care due to illness, disability or aging (%) | 975 (21.02%) |

| Village characteristics | |

| Distance between village centre and nearest county town (km) | 30.85 (35.13) |

| Collective village income per capita | 520.13 (2378.09) |

| Having a primary school | 2711 (58.45%) |

- Abbreviation: THC, township health centre.

3.2. Association of Telemedicine With Life Satisfaction and Satisfaction With Care

Table 2 presents the estimated association of telemedicine with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care. Columns 1 and 2 focus on the relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction, while columns 3 and 4 examine the association between telemedicine and satisfaction with healthcare. All regressions control for village characteristics, and columns 2 and 4 additionally control for individual and household characteristics. The results show a positive and significant association between telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and higher-level health facilities and both life satisfaction (coefficient = 0.324, p ≤ 0.001) and satisfaction with healthcare (coefficient = 0.327, p ≤ 0.001). That is to say, residents in villages with telemedicine collaboration reported life satisfaction and healthcare satisfaction that were higher by 8.1% and 8.2% of the total scale range, respectively, compared to those living in villages without such collaboration. In addition, we use satisfaction with local services as an alternative measure of life satisfaction. These results suggest that telemedicine collaboration is positively associated with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care among rural residents.

| Life satisfaction | Satisfaction with healthcare | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Village-level variables | ||||

| Telemedicine collaboration | 0.329 ∗∗∗ | 0.324 ∗∗∗ | 0.337 ∗∗∗ | 0.327 ∗∗∗ |

| (0.092) | (0.095) | (0.098) | (0.095) | |

| Closest distance between village office and county seat | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Collective village income per capita | −0.002 | 0.010 | −0.136 | −0.130 |

| (0.132) | (0.129) | (0.240) | (0.184) | |

| Having a primary school (vs. no) | −0.013 | 0.005 | 0.093 | 0.099 |

| (0.073) | (0.072) | (0.082) | (0.079) | |

| Individual- and household-level variables | ||||

| Age | 0.002 | −0.007 ∗∗ | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Female (vs. male) | −0.037 | −0.096 ∗∗ | ||

| (0.041) | (0.037) | |||

| Education (vs. not educated) | ||||

| Primary school | 0.072 | −0.047 | ||

| (0.065) | (0.052) | |||

| Middle school | 0.110 | −0.143 ∗∗ | ||

| (0.075) | (0.064) | |||

| High school | 0.154 ∗ | −0.112 | ||

| (0.082) | (0.059) | |||

| College or above | 0.261 ∗ | −0.022 | ||

| (0.112) | (0.087) | |||

| Having household members in need of care (vs. no) | −0.208 ∗∗∗ | −0.001 | ||

| (0.045) | (0.040) | |||

| Observations | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 |

| R-squared | 0.034 | 0.045 | 0.055 | 0.086 |

- Note: The table presents OLS estimates of the relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care of rural residents. Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

3.3. Association of Telemedicine With Life Satisfaction and Satisfaction With Care After PSM

Table 3 presents the estimated ATT of telemedicine for two key outcomes: life satisfaction and satisfaction with healthcare. After PSM, the standardised difference (% bias) between the treatment and control groups decreases significantly, with all covariates achieving balanced within the conventional 10% threshold (see Figure S1). In addition, the propensity score balance test indicates that, post-matching, the majority of observations in our analysis are on support (see Figure S2), demonstrating sufficient overlap in the distribution of propensity scores. After addressing potential selection bias, our results reveal statistically significant positive treatment effects (p ≤ 0.001). Specifically, the consistent ATT estimates—ranging from 4.092 to 4.095 for life satisfaction and fixed at 3.804 for satisfaction with healthcare across one-to-one, nearest neighbours and kernel matching—underscore the reliability of telemedicine’s positive impact. These findings provide robust empirical evidence that rural residents in villages with established telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and higher-level health facilities indeed experience significantly enhanced life satisfaction and satisfaction with care.

| Matching methods | ATT | SE | T value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | One-to-one matching | 4.095 ∗∗∗ | 0.037 | 8.13 |

| Nearest neighbours matching | 4.092 ∗∗∗ | 0.037 | 8.06 | |

| Kernel matching | 4.095 ∗∗∗ | 0.027 | 12.28 | |

| Satisfaction with healthcare | One-to-one matching | 3.804 ∗∗∗ | 0.034 | 10.54 |

| Nearest neighbours matching | 3.804 ∗∗∗ | 0.028 | 11.75 | |

| Kernel matching | 3.804 ∗∗∗ | 0.025 | 13.47 | |

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

4. Mechanism Analysis and Heterogeneity Analysis

4.1. Association of Telemedicine With Healthcare-Seeking Behaviour

One possible explanation for the positive associations of telemedicine with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care is its potential to enhance primary care services, thereby increasing the likelihood that rural residents seek medical care at village clinics. The results in Table 4 reveal that telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and higher-level health facilities is significantly associated with an increased likelihood of visiting a village clinic (coefficient = 0.118, p ≤ 0.05). That is to say, telemedicine collaboration increases the probability of village clinic visits by approximately 11.8% points, representing a modest yet significant shift in healthcare-seeking behaviour. This suggests that establishing telemedicine collaborations between village clinics and higher-level health facilities effectively encourages rural residents to seek care at village clinics more frequently, which in turn enhances their life satisfaction and satisfaction with care.

| Self-treatment | Village clinics | Township health centres | County-level or above hospitals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Telemedicine collaboration | −0.022 | 0.118 ∗ | −0.050 | −0.046 |

| (0.021) | (0.046) | (0.032) | (0.033) | |

| Individual, household and village characteristics included | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Observations | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 |

| R-squared | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.040 | 0.062 |

- Note: The table presents OLS estimates of the relationship between telemedicine and healthcare-seeking behaviour of rural residents. All regressions control for individual, household and village characteristics (including age, gender, education, having a household member in need of care, closest distance between village office and county seat, collective village income per capita and having a primary school in the village). Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

4.2. Association of Telemedicine With Healthcare Utilisation

Another possible explanation for the positive associations of telemedicine with life satisfaction and satisfaction with care is its potential to reduce healthcare burden on rural residents. Table 5 presents the estimated associations of telemedicine collaboration with household inpatient incidence, household inpatient expenditure and out-of-pocket household medical expenditure. The results show statistically insignificant reductions in both household inpatient incidence and expenditure for rural residents living in villages where local village clinics have established telemedicine collaboration with higher-level health facilities upon controlling individual, household and village characteristics (p > 0.05). This finding contrasts with telemedicine’s significant effect on healthcare-seeking behaviour, suggesting that its influence may be more pronounced in shifting care patterns than in reducing overall utilisation. Over all, our results suggest that there is limited impact of telemedicine on healthcare utilisation.

| Household inpatient incidence | Household inpatient expenditure | Out-of-pocket household medical expenditure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Telemedicine collaboration | −0.001 | −146.419 | −495.071 |

| (0.015) | (881.083) | (578.406) | |

| Individual, household and village characteristics included | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Observations | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 |

| R-squared | 0.062 | 0.014 | 0.018 |

- Note: The table presents OLS estimates of the relationship between telemedicine and healthcare utilisation of rural residents. All regressions control for individual, household and village characteristics (including age, gender, education, having a household member in need of care, closest distance between village office and county seat, collective village income per capita and having a primary school in the village).

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

4.3. Heterogeneous Effects by Type of Telemedicine Collaboration

The relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care may vary based on the type of collaboration established. Table 6 presents the estimated associations for different telemedicine collaborations. The results show that telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and township health centres is positively associated with both life satisfaction and satisfaction with healthcare (p ≤ 0.05). In contrast, the coefficients for collaboration with county-level or above hospitals are statistically insignificant. Furthermore, our statistical tests indicate that collaborations with both levels of providers yield the strongest associations, significantly outperforming single-level collaborations (p ≤ 0.05). For satisfaction with care, collaborations with township health centres show significantly stronger associations than collaborations with county-level or above hospitals (p ≤ 0.05). These findings suggest that, while multi-level collaboration appears to be the most effective, telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and township health centres appears to be more effective than higher-level collaborations in enhancing rural residents’ satisfaction with care.

| Life satisfaction | Satisfaction with healthcare | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Collaboration with THCs only | 0.215 ∗ | 0.211 ∗ | 0.297 ∗∗ | 0.292 ∗∗ |

| (0.104) | (0.105) | (0.111) | (0.109) | |

| Collaboration with county-level or above hospitals only | 0.124 | 0.110 | 0.037 | 0.008 |

| (0.091) | (0.087) | (0.092) | (0.082) | |

| Collaboration with both THCs and county-level or above hospitals | 0.568 ∗∗∗ | 0.584 ∗∗∗ | 0.577 ∗∗∗ | 0.557 ∗∗∗ |

| (0.126) | (0.128) | (0.129) | (0.123) | |

| Village characteristics included | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Individual and household characteristics included | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Observations | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 | 4638 |

| R-squared | 0.048 | 0.058 | 0.084 | 0.112 |

| p value: THCs only vs. county-level hospitals only | 0.485 | 0.429 | 0.011 ∗ | 0.012 ∗ |

| p value: THCs only vs. both | 0.007 ∗∗ | 0.006 ∗∗ | 0.028 ∗ | 0.033 ∗ |

| p value: County-level hospitals only vs. both | 0.003 ∗∗ | 0.001 ∗∗ | 0.000 ∗∗∗ | 0.000 ∗∗∗ |

- Note: The table presents OLS estimates of the relationship between different types of telemedicine collaboration and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care. All regressions control for village characteristics (including closest distance between village office and county seat, collective village income per capita and having a primary school in the village). Columns 2 and 4 additionally control for individual and household characteristics (including age, gender, education and having a household member in need of care). Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

- Abbreviation: THC, township health centre.

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

4.4. Heterogeneous Effects by Quality of the Workforce in Village Clinics

The relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care may be contingent on the quality of village doctors. On one hand, telemedicine may be less effective in areas with low-quality village doctors due to the specialised skills required for equipment operation and treatment provision. On the other hand, telemedicine could help compensate for skill deficiencies in areas with less-qualified village doctors by enhancing diagnostic and treatment capabilities. Table 7 presents the estimated associations for telemedicine based on the quality of the village doctors. We divide the sample into two groups based on whether their village doctors held formal medical qualifications, such as a ‘Practicing Physician’ license or an ‘Assistant Practicing Physician’ license, and those without licensed village doctors.

| Life satisfaction | Satisfaction with healthcare | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Village with licensed doctors | (2) Village without licensed doctors | (3) Village with licensed doctors | (4) Village without licensed doctors | |

| Telemedicine collaboration | 0.153 | 0.440 ∗∗∗ | 0.141 | 0.447 ∗∗∗ |

| (0.114) | (0.129) | (0.099) | (0.134) | |

| p value | 0.000 ∗∗∗ | 0.000 ∗∗∗ | ||

| Individual, household and village characteristics included | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Observations | 1678 | 2960 | 1678 | 2960 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.124 |

- Note: The table presents OLS estimates of the relationship between telemedicine and life satisfaction and satisfaction with care of rural residents by quality of village doctors. All regressions control for individual, household and village characteristics (including age, gender, education, having a household member in need of care, closest distance between village office and county seat, collective village income per capita and having a primary school in the village).

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

The results consistently show that the positive association between telemedicine collaboration and both life satisfaction and satisfaction with care is larger in magnitude and statistically significant (p ≤ 0.001) for the subgroup in villages served by unlicensed village doctors. In contrast, the estimated association is smaller and statistically insignificant for the subgroup in villages with licensed medical staff. Moreover, all specifications pass the between-group coefficient difference test. Overall, our findings suggest that the benefits of telemedicine in terms of improved satisfaction are amplified in rural areas characterised by a lower-quality village clinic workforce.

5. Discussion

Telemedicine services have been actively promoted by Chinese government to enhance access to healthcare in rural areas with limited resources. This paper aims to provide insight into the effectiveness of the telemedicine in improving satisfaction, reducing family healthcare burdens and encouraging the use of primary healthcare services. The findings shed light on several important aspects.

Overall, our findings reveal a positive association between telemedicine collaboration between village and higher-level health facilities and rural residents’ life satisfaction and satisfaction with care. These results held across different levels of telemedicine collaboration and are robust after controlling for individual, household and village covariates. The findings align with previous studies that have also reported high levels of patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life with telemedicine services [32–34]. Additionally, we find that telemedicine collaboration at village clinics had a spillover effect on residents’ life satisfaction. This suggests that telemedicine not only provides material resources but also offers symbolic resources in the form of information and meaning [35]. By strengthening village clinics, telemedicine supports and empowers rural residents by involving them in healthcare decision-making process, contributing to their overall well-being.

Telemedicine collaboration significantly influences health-seeking behaviour by encouraging rural residents to utilise village clinics, thereby strengthening the role of primary care in rural communities. This finding aligns with previous research in Massachusetts [36] and urban China [20], which find similar shifts in hospital choices following the implementation of tiered healthcare systems. Furthermore, our findings correspond to earlier work linking declining village clinic visits to increased bypassing of primary care and self-treatment behaviours [19]. Our research advances this understanding by demonstrating how telemedicine strengthens primary healthcare delivery in rural China through enhanced accessibility to specialist consultation and real-time expert collaboration [32]. Additionally, telemedicine facilitates continuous professional development for rural healthcare providers through knowledge exchange, ultimately elevating the standard of primary care delivery [37].

Furthermore, this study shows that the observed increase in satisfaction is not primarily driven by improved healthcare affordability. Despite a decrease in perceived healthcare burden in villages with telemedicine services, actual family healthcare spending did not decline. This could be due to increased utilisation of outpatient services at village clinics, potentially leading to higher healthcare spending. Simultaneously, telemedicine may encourage proactive healthcare practices, resulting in more frequent clinic visits. However, under China’s gradient reimbursement system, increased clinic visits and reduced higher-level facility visits may lower overall healthcare spending. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that telemedicine may not reduce healthcare spending [1, 22].

Finally, the study demonstrates substantial heterogeneity in telemedicine’s impact based on the collaboration type and healthcare workforce quality. Collaboration between village clinics and township health centres are more effective in enhancing care satisfaction than those involving county-level or above hospitals. This may due to closer ties, shared focus on primary care focus and established trust between township health centres and village clinics. These results align with evidence supporting telemedicine’s role in supporting communication between primary and secondary care [38]. Additionally, the results show that telemedicine is more beneficial in villages with a low-quality healthcare workforce. This is likely because telemedicine compensates for shortages by offering expertise from higher-level facilities and enabling ongoing training for less qualified doctors. These findings underscore telemedicine’s importance in addressing healthcare disparities’ remote areas lacking qualified professionals.

Our study has critical policy implications. Policymakers should prioritise expanding telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and higher-level health facilities. Given the increasing outpatient burden on primary care providers in remote areas [39], targeted resource allocation is essential for establishing an equitable and efficient healthcare system that advances universal health coverage goals [40, 41]. Efforts should focus on strengthening collaboration and integration between village clinics and township health centres through telemedicine initiatives. Additionally, telemedicine initiative should be prioritised in remote areas with underqualified healthcare workers to maximise its benefits on satisfaction. Although the overall quality of village clinic workforces remains low, village doctors have demonstrated effectiveness in certain scenarios, such as chronic disease management [42].

This study has certain limitations that should be noted. Firstly, the results may only reveal correlations rather than causation, as this study relied on cross-sectional data. While the top-down nature of telemedicine promotion ensures a degree of exogeneity in village-level adoption, the unobserved characteristic of village clinics may still influence the observed patterns. To mitigate this potential bias from village selection, we employ the PSM method. Secondly, the analysis of missing data patterns reveals that respondents with less direct healthcare experience were more likely to be excluded from our analyses. In addition, due to data limitations, we relied solely on subjective variables to quantify the effectiveness of telemedicine. Future research could explore clinical outcomes, such as life expectancy and complication rates, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of telemedicine’s impacts.

6. Conclusion

Telemedicine collaboration in rural primary care has been actively promoted by the Chinese government as a means of achieving universal health coverage. Our findings suggest that telemedicine collaboration between village clinics and higher-level health facilities is associated with improvements in life satisfaction and satisfaction with care among rural households. These positive associations are particularly pronounced in villages collaborating with township health centres and those served by lower-quality health workers. While telemedicine collaboration increased the utilisation of village clinics for health needs, it did not lead to a reduction in actual health spending. Strategies such as strengthening telemedicine collaboration at the local level and prioritising telemedicine resources for remote areas with lower-quality primary care workforces should be considered. These findings contribute to the understanding of telemedicine’s critical role in improving well-being in rural settings, offering insights into optimising the use of this emerging technology to strengthen primary care systems in China and other developing countries.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception or design of the work: Xintong Zhao and Miao Yu; data collection: Shaojie Zhou; data analysis and interpretation: Xintong Zhao, Qi Wang and Miao Yu; writing – original draft: Xintong Zhao and Qi Wang; writing – reviewing and editing: all the authors. All authors have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Renmin University of China (21XNF021) and the Key Project of the National Social Science Fund (24&ZD167).

Supporting Information

Table S1: Demographic comparison between CLS and CFPS. Table S2: Comparison of summary statistics between included and excluded samples. Figure S1: Standardised % bias across covariates before and after one-to-one matching. Figure S2: The common support of propensity score by one-to-one matching.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.