Exploring Ambiguity in Social Prescribing: Creating a Typology of Models Based on a Scoping Review of Core Components and Conceptual Elements in Existing Programs

Abstract

Introduction: Despite a growing social prescribing (SP) movement, the concept itself remains ambiguous, resulting in considerable variation in practice across different contexts. As discussions of SP emerge at the policy level, this ambiguity may influence program and policy spread. This research explores current literature and practices of SP to understand the different conceptual elements (i.e., goals and motivations) and core components (i.e., structures and behaviors) of SP.

Methods: A scoping review of academic literature was conducted. Search terms included “social prescr ∗,” “social medicine,” “link worker,” “social refer ∗,” and “community refer ∗.” From this data, a typology of models based on descriptions of conceptual elements and core components was developed. Following the development of the typology, we applied our findings to existing SP programs, which were found through reference-checking academic sources and a community consultation conducted by our partner organization.

Results: 29 articles informed the scoping review, and 24 program descriptions were compared to the typology. Four models of SP are proposed. The clinical model follows a biomedical approach where the physician refers patients to SP services primarily geared to lifestyle factors. The holistic model addresses social determinants of health, referring to food security, housing, or income programs. The empowerment model considers well-being through relationship-building and a deep understanding of the client context. The healthy community’s model focuses on community development, where community members gain the capacity to better support one another.

Conclusion: The proposed typology will help implementers design programs that best suit their goals and contexts. At the policy level, this research demonstrates how a “bounded ambiguity” approach may allow SP to demonstrate its fullest potential. For researchers, this work provides a foundation for future exploration of how SP is implemented despite its ambiguity.

1. Introduction

Social prescribing (SP) is a term coined in the United Kingdom that describes the practice of connecting health, social, and community services to provide patients with a more holistic healthcare experience [1–3]. SP practice has grown from initial grassroots movements [4] to institutionalization within the National Health System (NHS) as part of the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan [5], making it a leading example of SP implementation at the system level. Advocates in many countries, including those working in many provincial health systems across Canada [6], are now looking to follow suit.

Despite the rapid growth of SP, the meaning of the term itself has largely remained unclear, and its use has been inconsistent in both literature and practice [7–9]. For example, SP has been described as “a means of enabling health professionals to refer people to a range of local, nonclinical services” [10] which allows for a bespoke service delivery experience for patients, [11, 12] and alternatively as a tool to address growing health disparities and health inequities within biomedically dominant health systems by shifting attention toward the social, political, structural, and economic influences, collectively described as the social determinants of health (SDoH) [7, 10, 13, 14]. While not necessarily inconsistent, these different descriptions suggest different underlying objectives for SP that may influence its operationalization in practice. Reviews of SP across various contexts suggest that there have been different iterations of SP, with different sources of referral, processes, and target populations [8, 15]. For program planners and policymakers seeking to support the adoption of SP more broadly, this raises the question of which SP model to implement [8, 16, 17].

The existence of the various iterations of SP and inconsistency in its definition demonstrates the ambiguity of SP. In policy literature, ambiguity refers to the “ability to interpret a policy problem, and therefore try to solve it, in profoundly different ways” [18]. Policy ambiguity can arise from ambiguity of goals (i.e., expected outputs or outcomes) or means (i.e. tools, structures, and behaviors) to achieve them [19]. Ambiguity is often associated with “uncertainty,” which describes a lack of understanding of a concept or policy. However, unlike uncertainty, ambiguity cannot be mitigated with greater knowledge or evidence [18, 20]. Rather, ambiguity is resolved through the framing of a policy, or how policymakers choose which interpretation of a policy to support [18]. Reducing ambiguity can therefore aid top-down policy implementation [18, 19], which is characterized by one centralized decision-making body disseminating ideas to local jurisdictions [19, 21, 22].

On the other hand, some proponents argue that ambiguity can allow tailoring to context, which can support more targeted and effective policy implementation at the local level [23]. Rigid implementation guidelines may only be possible for clearly defined policy problems rather than for those that are complex and multifaceted such as addressing health disparities or health equity, where there are no clear-cut solutions. Scholars have argued that the flexibility of ambiguous policies allows for more creative thinking, opening the potential for innovation and experimentation that can result in more radical and change-oriented policies or programs. Often this kind of experimentation can occur at the level of individual community-based efforts characteristic of bottom-up implementation [23]. In the case of SP, this flexibility can be considered a strength, providing benefits from different models of SP in different contexts [16, 17, 24].

As SP continues to work its way into health systems, a fine balance is needed between the practicality of clear-cut parameters for goals and means and the ambiguity that can foster creativity, thereby allowing the full potential of SP to be achieved in different contexts. Previous scoping reviews have identified how SP models can vary by “intensity” [25], planning stages, practices [8], and motivations [9]. While these existing reviews help in understanding the variation of SP, there has yet to be a comprehensive framework of models that considers the specific goals and motivations of the implementers and the observed structure and practice of SP. Our research seeks to address this gap and contributes to the understanding of whether, and if so, how the ambiguity of SP has been leveraged to support implementation.

At the time of conducting this research, there was no universally agreed definition of SP [17]. For the purposes of this research, we followed Polley et al.’s [26] description of key components of a SP program: (a) a referral from a healthcare practitioner or allied health professional, most often a family physician, that connects the patient or client via a “social prescription” to (b) a connector or link worker, defined to be a trusted individual [7], who connects the patient or client to (c) an array of services in the community. To ensure consistency in this paper, the term connector is used to encompass the various titles that the role can have (i.e., link worker and navigator) in different contexts.

2. Methods

In partnership with the senior manager of strategic initiatives and capacity building and the SP project manager at United Way Halton & Hamilton, a local nonprofit organization (the partner), our aim was to develop a typology of SP models for implementation consideration in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The partner’s intent was to share the typology with an advisory council of local clinical and social service providers to help in determining which model of SP would best fit the goals within the community.

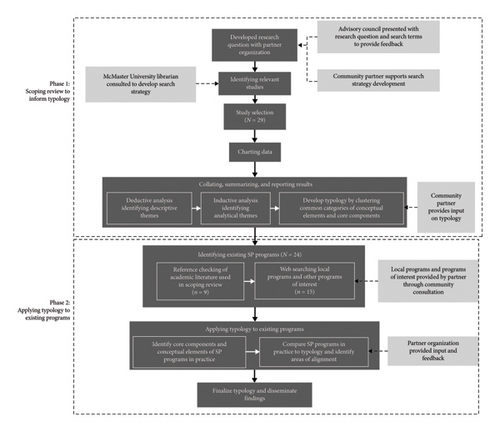

Figure 1 provides an overview of the research process, which was conducted in two phases. The first phase was a scoping review to develop a typology of SP models. The second phase examined how well existing SP applications in the Canadian context aligned with the models identified in the typology. The focus on Canadian SP applications reflected the partners’ objective to identify approaches for SP that might align with the objectives and constellation of existing services in the local community. The partner provided input throughout all phases of the research. The Advisory Council also provided input on the research question and search terms.

2.1. Phase 1: Scoping Review to Inform Typology

A scoping review [27] was conducted to explore the academic literature on SP to answer the research question: “What are the conceptual elements and core components of SP that are described in the academic literature?” Our focus is on conceptual elements and core components aimed at understanding the correspondence between the objectives and underlying values of a given SP application and the key features of its implementation. Scoping reviews have been used to (a) explore the breadth of the literature available on a certain subject, (b) determine the value of conducting a more resource-intensive systematic review, (c) summarize the current state of research, and (d) identify areas in need of further exploration [27]. We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for conducting a scoping review, which includes six steps: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; collating, summarizing, and reporting the results; and consultation [27].

We created a typology of conceptual elements and core components as a structure to summarize our findings. We excluded gray literature from our search after an initial review revealed that it focused on describing programs in practice without capturing important conceptual elements (e.g. beliefs about health and core values) that were needed to develop our typology.

2.1.1. Academic Literature Search

The search of the academic literature was conducted in September 2021 and updated in December 2023. The search strategy was developed with the community partner, input from the Advisory Committee and a McMaster University research librarian. The databases were selected to capture interdisciplinary perspectives on SP and included AgeLine, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, Politics Collection (Public Affairs Information Service, Policy File Index, Political Science Database, and Worldwide Political Science Abstracts), PubMed, Social Sciences Abstract, Social Sciences Citation Index, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science. Search terms included “social prescr ∗,” “social medicine,” “link worker,” “social refer ∗,” and “community refer ∗.” The individual search terms were adjusted for each database.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) defining SP, (b) describing conceptual elements that motivated the adoption of a SP approach, and (c) describing the core components which characterize SP in practice. Exclusion criteria included (a) nonpeer-reviewed academic literature such as study protocols, poster descriptions, and conference proceedings and (b) articles not written in English. Researchers and partners agreed to set no date limits as the known literature on SP was relatively scarce. Due to the wide variety of articles and typical scoping review practice, quality appraisal was not conducted.

Literature found in the academic search was organized using the citation and reference management software, EndNote. Once titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and duplicates were removed, LB identified a purposive sample of articles (n = 10), where the core components and conceptual elements were less explicitly described to serve as a basis for clarifying criteria for inclusion. Both LB and GM then reviewed this sample independently and came together to identify which articles would be included. Once consistency in full-text screening was established, the rest of the literature was screened by LB. Following this process, titles and abstracts of selected articles were downloaded from EndNote and organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet [28]. Data extraction followed a similar exercise, in which a purposive sample of the selected literature (n = 5) was analyzed independently by LB and GM to ensure consistency in extraction. In cases where disagreements arose, the authors discussed together until consensus was achieved. Once consistency was established, LB continued to extract data from the remaining literature.

Extracted data from the academic literature search was first inputted into a table in Microsoft Word [29]. Data extracted included title, purpose of the research, research design, definition of SP, examples/models discussed, any statements pertaining to conceptual elements, any statements that described the operation of the program in practice in terms of its core components, and authors’ interpretation of the work.

2.1.2. Typology Development

According to Arksey and O’Malley [27], scoping reviews require an analytic framework or thematic construction to develop a narrative of the found literature. For our review, we used the thematic categories of conceptual elements and core components to structure our thematic synthesis [30].

Extracted data were first coded deductively line by line to identify descriptive themes within core conceptual elements and core components. Four subcategories of conceptual elements were identified. Similarly, four subcategories of core components were also identified.

Following this, analytic themes were identified inductively from the data to arrive at our four models of SP presented in the typology, each exhibiting its own cluster of conceptual elements and core components. For example, when developing the holistic model, we found that the combination of conceptual elements of believing health was a result of biological, physiological, and social factors; core values of holistic, person-centered care and of SP being a necessary tool to address the SDoH [16] tended to be reflected in SP models whose core components included professionally (not clinically) trained connectors (e.g., health promoter and social worker) [31] operating within interdisciplinary healthcare team settings [32]. The analytic themes were discussed and refined iteratively with input from the partner until clarity and consensus about the different models and their interpretations were achieved.

2.2. Phase 2: Applying Typology to Existing SP Programs

Following the development of our typology, we worked with the partner to apply our theoretical findings to SP programs in practice. For this activity, we initially identified existing programs through reference checking of the academic literature found in our scoping review (N = 9), all of which are located outside Canada (in the United Kingdom), and through program suggestions from a community consultation led by our partner (N = 73), all located in Canada. The latter were narrowed down to 15 programs which met two criteria: (1) self-identified as SP, or (2) meeting Polley et al.’s three key components of a SP scheme. These 15 Canadian and nine programs outside Canada were then compared with the four models of the typology in terms of the alignment of their conceptual elements and core components. The authors discussed and agreed that an existing program was deemed to align with one of the models in the typology if its description aligned with at least three of the four conceptual elements and at least three of the four core components associated with the model. In cases where an existing program aligned with all four conceptual elements, but with half the core components of the two models (or vice versa), it was described as a hybrid model. For example, if a program aligned with all four core components of the holistic model, and two conceptual elements of the holistic and two conceptual elements of the empowerment model, we described it as a holistic-empowerment model. The lead author reviewed all programs to identify alignment between existing programs and typology models.

3. Results

The search of academic databases yielded a total of 3626 articles (Figure 2). After duplicates were removed, 1308 article titles were screened for relevance. Of these, 486 articles were retrieved for full-text screening.

A total of 29 articles were selected for the academic review. Studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 20), Canada (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), and the United States (n = 1). An overview of the included studies’ objectives and methods from the academic literature is presented in Table 1.

| Article | Year | Country | Study purpose | Program of interest/context | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker and Irving [33] | 2016 | United States | To understand the operation of a codesigned SP pilot | SP for older adults with early-onset dementia | Evaluation of a local SP program |

| Bertotti et al. [34] | 2018 | United Kingdom | To understand what worked in a SP pilot, for whom, and under what circumstances | SP pilot in the United Kingdom | Realist evaluation of a local SP program |

| Bradley and Scott [35] | 2021 | United Kingdom | To explore the language used in SP and the implications on policy and practice | SP programs in primary care settings and the role of occupational therapists | Commentary applying the theory of institutional work to SP |

| Brettell, Fenton, and Foster [36] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To describe an evaluation of a SP program for children and youth’s mental health | Local SP program for service users aged 16–25 in the United Kingdom that aims to connect children and youth to services and activities in the community to improve health and well-being | Quantitative evaluation of the effect of SP intervention on loneliness and well-being |

| Griffith et al. [37] | 2023 | United Kingdom | To understand how connectors navigate the different interpretations of SP | SP program in the United Kingdom serving individuals aged 40–74 with chronic conditions living in an area of high socioeconomic deprivation | Ethnographic research of connectors |

| Grover et al. [38] | 2023 | Canada | To synthesize findings of qualitative studies on the impact of SP on older adults | SP programs for older adults | Systematic review of qualitative studies on the experiences and impact of SP on older adults |

| Hassan et al. [39] | 2023 | United Kingdom | To identify facilitators and barriers to sustainable SP programs across the United Kingdom | SP programs in the United Kingdom | Findings from the workshop and survey |

| Howarth and Burns [40] | 2019 | United Kingdom | To identify the role of nurses in SP practice | Nurses practicing SP in the United Kingdom | Policy recommendations on the role of nurses in SP |

| Islam [16] | 2020 | Australia | To describe compelling aspects of SP in primary care settings | SP in primary care settings | Narrative synthesis of peer-reviewed and gray literature |

| Jani [41] | 2019 | United Kingdom | To describe the role of SP in addressing the social determinants of health | SP programs in the United Kingdom | Literature review on the development and growth of the SP movement |

| Kurpas et al. [42] | 2023 | Poland | To describe the opportunity for SP to integrate health and social care in the community | SP literature describing programs serving the elderly living in rural settings | Perspective paper on the potential of SP in integrating health and social care in the community |

| Lee et al. [24] | 2022 | Singapore | To describe the process of planning, implementation, and scaling of a SP program in Singapore | SP program in Singapore | Lessons learned from SP implementation |

| Marx and More [43] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To describe the development of a nature-based SP program | Nature-based SP program with additional support to improve attendance [43] | Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis |

| Morse et al. [15] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To describe the international growth of SP practice seen across 17 countries | SP programs and practices across 17 countries | Qualitative interviews with SP experts across the globe |

| Nowak and Mulligan [44] | 2021 | Canada | To describe the role of SP in primary care | SP in primary care settings | Case descriptions of SP in practice and recommendations for the Canadian context |

| Pearce [11] | 2020 | United Kingdom | To describe the work and benefits of SP across the United Kingdom | SP programs in the United Kingdom | Literature review on the implementation of SP across the United Kingdom |

| Polley [17] | 2016 | United Kingdom | To describe the state of SP in the National Health System (NHS) | SP practice in the United Kingdom | Describes the state of SP in the United Kingdom with policy recommendations |

| Rapo et al. [45] | 2023 | Sweden | To identify “critical components” [45] of SP | SP programs focusing on older adults’ loneliness, health, and well-being | Systematic review of SP programs |

| Rempel et al. [46] | 2017 | United Kingdom | To review and evaluate the aims and measures of social referral programs | Social referral or SP programs in the United Kingdom | Literature review of social referral/SP programs |

| Roberts and Heiss [47] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To understand the perceived importance of various skills needed for SP connectors | SP programs across Wales | Group concept mapping to identify the most relevant skills for connectors |

| Robinson [12] | 2018 | United Kingdom | To describe the potential of SP in improving patient outcomes and reducing waste in the NHS | SP programs in the United Kingdom | Perspective article describing a SP program |

| Sandhu et al. [48] | 2022 | Netherlands | To understand the role of connectors, refer to activities and target populations | Published evaluations of SP programs | Literature review of evaluations of SP |

| Santos-Tapia et al. [49] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To identify and categorize the different components of “link worker (SP)” [49] | SP programs in the United Kingdom | Scoping review of peer-reviewed literature |

| Thomas, Lynch, and Spencer [50] | 2023 | Spain | To describe the creation of a codeveloped SP program | Nature-based SP program to address loneliness in urban deprived neighborhoods | Case study of an ongoing program |

| White et al. [51] | 2021 | United Kingdom | To explore the use of coproduction and codesign methods in SP to establish standards for coproduced SP programs | Community settings (interventions provided in communities of any density) | Systematic review of the literature describing the use of coproduction in SP |

| Wood et al. [52] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To describe the findings of a SP evaluation | SP program in the United Kingdom | Evaluation of the SP program |

| Wood et al. [53] | 2021 | United Kingdom | To “refine a program theory explaining the underlying mechanisms of operation in SP” [53] | SP program in the United Kingdom | Realist evaluation |

| Morse et al. [15] | 2022 | United Kingdom | To understand the mechanisms of green SP that contribute to improved mental health outcomes | Community gardening SP program in the United Kingdom | Thematic analysis of qualitative interviews |

| Younan et al. [31] | 2020 | United Kingdom | To examine the impact of SP in population health settings to understand how SP would apply in COVID-19 settings | SP program in the United Kingdom | Describes representative SP schemes at different levels of intervention: individuals, communities, or both |

- Abbreviations: NHS, National Health System; SP, social prescribing; UK, United Kingdom.

The initial themes pertaining to conceptual elements and core components as extracted from the selected academic articles are presented in Table 2.

| Article | Conceptual elements | Core components |

|---|---|---|

| Baker and Irving [33] |

|

• Referrals made by GPs, community health workers, and shelter accommodation managers |

| Bertotti et al. [34] |

|

|

| Bradley and Scott [35] |

|

|

| Griffith et al. [37] |

|

|

| Grover et al. [38] |

|

|

| Hassan et al. [39] |

|

• Third sector with sufficient capacity to support SP participants and evaluate findings |

| Howarth and Burns [40] |

|

|

| Islam [16] |

|

|

| Jani [41] |

|

|

| Kurpas et al. [42] |

|

|

| Lee et al. [24] |

|

|

| Marx and More [43] |

|

|

| Farre and Rapley [54] |

|

|

| Rapo et al. [44] |

|

• Referrals made by GP |

| Pearce [11] |

|

• Connectors integral to SP practice |

| Polley [17] |

|

|

| Rempel et al. [45] |

|

|

| Roberts et al. [46] |

|

|

| Rothe and Heiss [47] |

|

|

| Robinson [12] |

|

|

| Rothe and Heiss [47] |

|

|

| Santos-Tapia et al. [49] |

|

|

| Thomas, Lynch, and Spencer [50] |

|

• “Menu” of local nature activities, SP/health, and civil organizations |

| White et al. [51] |

|

|

| Wood et al. [52] |

|

|

| Wood et al. [53] |

|

• Connector, who is a “…professional who supports person and links services and agencies involved in their care” [53] |

| Younan et al. [31] |

|

|

- Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; SP, social prescribing.

Based on the themes extracted from the academic literature, we define conceptual elements in our typology to include the general beliefs about health, core values of healthcare, importance of SP, and overarching objectives of the SP program. We similarly define core components as characteristics of SP program implementation, including entry point, connector, offerings, and setting. Our inclusion of “setting” expands Polley et al.’s key components. Here, setting refers to the environment in which the referrer is placed, and therefore where SP is accessed. The typology of models of SP derived from our analysis of the academic literature (Table 3) presents a menu of four model options for those considering implementing SP locally: clinical, holistic, empowerment, and healthy community models. Each model is comprised of a characteristic set of conceptual elements and corresponding core components and is discussed briefly in turn.

| Model | Conceptual elements | Core components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about health | Core values | Importance | Objectives | Entry | Connector | Offerings | Setting | |

| Clinical | Result of biological and physiological factors |

|

SP as optional, enhances services | Broaden array of services | Physician referral | Clinically trained system navigator | Services that complement clinical treatment | Physician’s office |

| Holistic | Result of biological, physiological, and social factors |

|

SP as necessary | Address SDoH |

|

Professionally trained system navigator (e.g., health promoter) | Services that offer treatment options for clinical conditions related to SDoH | Interdisciplinary healthcare team |

| Empowerment | Focus on overall well-being in addition to biological and social factors |

|

SP as necessary | Allows people to have greater control of their health | Healthcare team self-referral |

|

Services that address social isolation and increase the social capital of the individual, leading to personal empowerment | Interdisciplinary healthcare team |

| Healthy community | Sense of connection and community |

|

SP as a core part of the community, alongside healthcare | Creating a stronger, resilient community | Self-referral to training | Any member of the community who has received training can take on the connector role | Services that provide training for community members to recognize need and connect others to services when required |

|

3.1. Clinical Model

This model is built upon conceptual elements that align with the biomedical model of health, in which health is believed to be largely a result of biological and physiological determinants [55]. Core values include being clinically led (mainly physicians), with evidence-based care supported by rigorous clinical research and patient-centeredness. SP broadens existing services to include nonclinical options as a desirable “add-on” to clinical services, thereby increasing their perceived legitimacy [16]. The point of entry into SP is through a referral by a medical professional, most commonly a family doctor. Through a medical visit, physicians may identify the importance of lifestyle factors (e.g., exercise) and would provide an associated social prescription either by direct referral to relevant services (often called signposting), or by referring the patient to an outside connector who would direct the patient to relevant services.

3.2. Holistic Model

In this model, health is conceptualized as resulting not only from biological and physiological determinants but also from the SDoH. Core values include offering holistic and person-centered care. Here, SP broadens available services to support SDoH, such as income, food security, and housing, and is viewed as a necessary complement to medical treatment. The point of entry is commonly through a physician, but allied health practitioners may play a role, and self-referral has been seen in practice. Typically, connectors are presently acting as system navigators, with appropriate training to work with each program’s target population. The most significant difference in practice from the clinical model is that the patients’ social context is addressed, which in turn affects their clinical conditions.

3.3. Empowerment Model

This model follows a salutogenic perspective [56] and aims for overall well-being rather than strictly clinical recovery. WHO describes well-being as “…encompassing quality of life and the ability of people and societies to contribute to the world with a sense of meaning and purpose.” The core values of this model are self-efficacy, self-determination, and personal empowerment. SP is viewed as a necessary tool to give patients greater control of their own health. Services are typically offered in interdisciplinary team-based healthcare settings. The connector’s role includes building deep and lasting relationships that lead to a better understanding of the person’s social situation, which can help to empower the person within their care and social contexts. The most significant difference between the holistic and empowerment models is the empowerment model’s emphasis on the relationship between the connector and the client, as well as the overall aim of this service being to achieve well-being, not just health.

3.4. Healthy Community Model

This model also falls under the well-being improvement aim but markedly differs from the others by focusing not only on individual well-being but also on community well-being. It recognizes that healthy communities offer a sense of connectedness and belonging that simultaneously promotes individual well-being [12]. Values that underlie this model are asset-based approaches, community development, and extensive community and partner engagement. SP is implemented with the intent to foster “health-creating communities, wherein community members can take care of themselves and each other” [16]. This model goes beyond the healthcare system by offering training and capacity building to interested community members, so that they can recognize needs and direct community members (themselves, family, neighbors, and friends) toward beneficial services. In this way, any community member who has received the training can become a de facto connector. Interested community members can self-refer to the training program to become volunteer connectors.

3.5. Comparison to Programs in Practice

Table 4 presents the findings of the application of the typology to the existing programs. Programs with an asterisk self-identified as being SP. Among the 15 programs from Canada, only five self-identified as SP, whereas all of the United Kingdom programs (n = 9) self-identified as SP.

| Locationa | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Clinical | |

| Ontario, Canada | The program aims to provide patient-centered care. Services are for those with an abnormal cancer screening result and are not considered mandatory to the treatment plan. The program is accessed in a clinical setting. Connector helps patients with an abnormal screening result to navigate the next steps in the care process, including social support |

| Ontario, Canada [57] | The program aims to provide patient-centered care to individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers by broadening the array of services available. Services can be accessed either by a GP referral or through self-referral. Services themselves are situated within a nonprofit organization. Connector is trained but not a clinical professional |

| Holistic | |

| Ontario, Canada [58] | The program aims to provide holistic care, person-centered care to individuals in need of multiple different services. Situated within the social service sector, the connector coordinates individuals using various social and health services, with the goal to divert individuals from crisis situations. Connector has extensive experience in the social service sector |

| Ontario, Canada [59] | The program approaches health through a social and cultural lens for Indigenous patients recently diagnosed with cancer. Program situated within a hospital, where the connector helps patients navigate both clinical services and culturally relevant and spiritual services |

| Ontario, Canada [60] | The service aims to provide holistic, person-centered care to existing patients of a family health team. Services can be referred to by a GP or allied health professional within the team. Connector is professionally trained and works with patients to address external stressors that are affecting their health and quality of life |

| Ontario, Canada [61] | The program aims to address the SDoH associated with mental illness. Uses a holistic approach to crisis diversion. Service is accessed through law enforcement but is provided by an allied health professional who refers clients to appropriate clinical and social services to address immediate needs |

| Ontario, Canada ∗ | The program aims to address SDoH associated with food insecurity. Program is housed within a community health center and is referred to by either a GP or an allied health professional. Prescriptions are given to increase accessibility to healthy food through subsidized food markets |

| Ontario, Canada [62] | The program addresses the SDoH of food insecurity. The program is accessed by clients through a community health center, where either a GP or allied health professional can refer out to a national nonprofit to get more accessible healthy food options |

| British Columbia, Canada ∗ | The program aims to provide holistic, person-centered care to senior populations that address the SDoH. Services can be accessed through GPs, allied health professionals, or self-referral. Services are housed within local community centers, where connectors help clients navigate services such as physical activity groups, medical transportation, nutrition, and food service programs |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to provide person-centered care to patients. Services can be accessed through a GP or self-referral. Connectors are in a nonprofit organization and work with clients to identify relevant services that can span from clinical to social support to help individuals to maintain their independence from the healthcare system |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program is an expansion of an existing SP program. It aims to specifically address SDoH related to mental illness. Referrers can be GPs, allied health professionals, or self-referral. Connectors work with clients to find services to complement clinical treatment and divert from emergency services |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program seeks to address SDoH and social isolation. Services can be accessed through a GP or self-referral, where free admission to local museums is available to clients |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to improve the quality of life and well-being of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or dementia through referrals to arts-based activities. Services are accessed through a GP, allied health professional, or self-referral |

| Empowerment | |

| Ontario, Canada [63] | The program aims to increase the overall sense of well-being through increasing self-efficacy and self-determination. SP is a necessary tool to connect patients to culturally safe and relevant care, thus allowing for greater control over one’s health. Program is situated within an interdisciplinary hub, with the connector understanding and providing culturally relevant care |

| Ontario, Canada ∗ | The program aims to improve the overall well-being and quality of life of patients. Situated within a family health team, where prescriptions are provided by GPs or allied health professionals who are part of the health team. Activities referred to include nature walks, a plant prescription, and other eco-friendly activities |

| Ontario, Canada ∗ [64] | The program aims to address social connection and physical activity in older adults. Services are accessed through either GPs, allied health professionals, or self-referral, where clients are referred to a local nonprofit, where a connector works with the client to find activities that improve physical activity and foster social connection |

| British Columbia, Canada ∗ [65] | The program aims to increase well-being through making activities in nature more accessible. Program can be accessed through primary care practitioners or self-referral. Services offered include free admission to local parks to address financial barriers, physical activity, and overall well-being |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to address social isolation and increase feelings of control over one’s health. Services are accessed through a prescription from the GP, which then goes to an external volunteer and community services organization who works with clients to find services such as lunch clubs, gardening groups, and other social activities |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to improve overall well-being. Services can be accessed through a GP or through self-referral to the local voluntary community services. A connector then works with the client to identify social activity programs of interest |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to address the sense of belonging and well-being. The program is accessed within a health center through a referral by GP to a connector, who works with patients to find activities which could include gardening, cooking clubs, and conversation partners, among many more |

| Healthy community | |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to develop resilient communities, where community members volunteer to receive ongoing training to be able to support and refer friends and neighbors to available health and social services in the community. Monthly training opportunities are also provided to connectors to continue to learn about the community |

| Hybrid models | |

| Holistic-empowerment | |

| Ontario, Canada [66] | The program aims to address SDoH in the local neighborhood, while also increasing self-efficacy in clients. Service was viewed as a necessary tool to provide holistic care to equity-deserving populations. Service was located within the community to make services more accessible, allowing individuals to take control of their own health. Connector was a registered nurse familiar with the neighborhood |

| Ontario, Canada [67] | The program aims to address social isolation and overall well-being in clients, while also addressing barriers associated with SDoH (e.g., income and environment). Clients are referred to by their GP who refers them to local museums to get free admission. The conceptual elements of the program fall under empowerment (i.e., addresses isolation and sense of well-being), but core components are closer to holistic (i.e., clinical setting to referral; no relationship-building). |

| Empowerment-healthy community | |

| England, United Kingdom ∗ | The program aims to create resilient communities and empower community members to take control of their own health. Program can be accessed through self-referral, health connector, or GP. Connectors then work with clients to identify activities or services of interest, one of which is to volunteer and be trained as a health connector themselves |

- Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; SDoH, social determinants of health; SP, social prescribing.

- aPrograms marked with a ∗ have self-identified as SP.

All self-identified SP programs (n = 14) aligned with at least one of the proposed models. Models that did not self-identify as SP (n = 10) also aligned with at least one of the models. From this comparison, two programs aligned with the clinical model, 11 aligned with the holistic model, seven aligned with the empowerment model, and one aligned with the healthy community model.

Three programs aligned with more than one of the proposed models (hybrid models). Two of these programs aligned with both the holistic and empowerment models. Neither program self-identified as SP. One program was identified as a system navigator service, and the other was a program that specifically addressed accessibility to recreational activities. Both programs included conceptual elements of both the holistic (e.g., addressing barriers such as income or transportation) and empowerment models (e.g., increasing the sense of control over one’s health and improving the sense of well-being). In practice, both models more closely aligned with the core components of the holistic model and lacked the relationship-building found in the empowerment model. Another hybrid program aligned with both the empowerment and healthy community models, aiming to increase the sense of belonging and overall well-being while creating a resilient community. The program offered services to address social isolation and offered the opportunity to undertake training and volunteer to become a health connector. These hybrid models suggest that the boundaries between the proposed models can be fuzzy and that they may fall along a continuum.

4. Discussion

As previously discussed, ambiguity can be applied to two aspects of policies: goals, or the intended outcome and impact of a policy (conceptual elements in our typology) and means, the specific actions needed to implement the said policy (core components). Our typology suggests that means may be dependent on goals, as there appears to be a correspondence between certain conceptual elements and core components. For example, in the clinical model, where core values of healthcare delivery include being clinically led, evidence-based, and patient-centered, clinically trained health professionals are most often found to be integral to the SP program, taking the role of the referrer and, in some cases, the connector. In other models, such as the empowerment model, where self-determination is valued more highly than professional dominance, we see more examples of self-referral, or connectors who are trained in principles of health promotion, which promotes more client-led decision-making. As SP continues to grow and advocates push for its inclusion in health systems, we have seen efforts to mitigate the ambiguity around SP. Recently, an international consensus of conceptual and operational definitions for SP was published [7]. These definitions outline the distinct conditions that must be achieved to be considered SP [7]. For policymakers, the creation of a definition in itself can act as a facilitator of top-down policy implementation as it distinguishes SP from other programs. However, SP also has been described as a community-led, grassroots practice [4, 12, 16, 17], which is more conducive to bottom-up implementation [19, 23, 68]. Having distinct criteria to ascribe to can hinder the codesign and coproduction processes in developing SP practices, which have been identified as necessary for implementers aiming to achieve health equity [7, 23, 51].

Our typology suggests that SP may fall along a continuum, rather than a discrete set of conditions that need to be met. The typology demonstrates what we call “bounded ambiguity,” which allows freedom to contextualize SP programs in practice based on suggested models to meet local and immediate objectives, while aligning with a defined set of operating parameters. We identify three benefits of embracing this “bounded ambiguity” approach through the use of our typology.

First, it makes SP more accessible to various potential implementers allowing them to choose models that best align with current policy objectives and feasibility while also opening the opportunity to move along the continuum to meet changing objectives. For example, implementers looking to use SP as a means to introduce more holistic approaches to a biomedically dominant health system may find it easier to initially implement the clinical model of SP. Over time, as the practice of including more service offerings for patients becomes common place, additional changes can be made to the core components to better reflect the intention of addressing the SDoH in their practice. This may mean expanding their SP program to include income support, or other relevant options. This aligns with the College of Medicine’s description of SP as a “…Trojan horse for extending and enabling health-creating communities.”

Second, our typology is also a visual aid to help communicate not only what SP is but also what it can be. While some SP programs may follow the holistic model, this typology can demonstrate how additions to core components or conceptual elements can create an empowerment model. The hybrid models found in our comparison to existing SP programs may demonstrate this gradual movement across the SP continuum. The typology also allows implementers of SP programs and policymakers to conceptualize how SP can result in larger, system-level changes. At its full potential, the broadening of services that SP enables may direct greater policymaker attention to the benefits of social and community services, thus increasing funding to historically underfunded sectors [16, 41]. By providing options outside of the healthcare sector, health professionals are able to divert patients from unnecessary medical treatment to more appropriate resources, thus reducing the burden on an overworked sector [12].

Finally, the flexibility in our typology also can serve as a communication tool for policymakers and program planners who may have divergent perspectives on SP implementation. By centering the role of the conceptual elements (i.e., general beliefs about health, core values of healthcare, importance of SP, and overarching objectives of the SP program), our typology offers an opportunity for potential partners to surface common values that are not often clear in everyday discussion. Policymakers and program planners can then see an example of how common values can be operationalized through corresponding core components.

At the same time, there are valid concerns with a lack of clarity regarding SP. Significant variation in implementation and practice makes comparison and measurement difficult, resulting in a weak evidence base [34, 40, 45, 51]. Ambiguity can also lead to the dilution of the concept, resulting in disingenuous use of the term in an effort to capitalize on SP’s growing momentum. Lack of clarity in SP also has the potential to exacerbate issues of medicalization of social needs [12]. Overmedicalization is defined as occurring “when the institution of medicine steps over its proper limits.” A notable negative impact of overmedicalization is a less than optimal use of scarce resources [69].

The findings of this study help with the understanding and practice of SP. While other SP typologies have been proposed [8, 25], they have not made explicit the underlying goals and motivations of SP programs. By making these concepts overt, the proposed typology can offer support to public policymaking, allowing the advancement of a variety of models suited to different contexts and objectives. For practitioners and implementers, the proposed typology of SP models can help align goals and intent for SP adoption (i.e., conceptual elements) with the structure and practice of the program being developed (i.e., core components). With a more explicit understanding of the conceptual elements associated with each model, it may be easier to cocreate hybrid SP programs that best suit the mix of partners involved. For policymakers, this consideration of ambiguity in policymaking allows for reflection on how to best approach not only SP as a policy tool but also other similarly community-based innovations to best realize their potential. This tool can also be used to understand how various levels of decision-making, local, provincial, or federal, may perceive SP. By understanding these differences, if any, advocates would be able to identify ways to bridge the gap between the various decision-makers. For researchers, this typology can be used as a tool to better understand SP in its various contexts. Using this typology, researchers may be able to overcome barriers to evaluation in SP by comparing indicators and outcomes of programs using the same model (e.g., evaluating the efficacy of the clinical model of SP on specific health outcomes).

5. Limitations and Strengths

This research is subject to several limitations. First, it is important to note that the names of the “models” listed in the typology were coined by the researchers and may not resonate with the developers of the programs they represent in practice. Furthermore, few programs will capture each element exactly; some overlap may exist between models in some programs, as demonstrated by the hybrid models when compared to the gray literature. To address these concerns as much as possible, the researcher and partners spent considerable time teasing apart each conceptual element and core component through iterative discussion and referring to the original literature.

The selected models may not necessarily be representative of all SP programs, especially considering the focus on Canadian programs, which was a result of the collaborative nature of this research. We have made an effort to offset this limitation by including SP programs that were drawn from the academic literature.

In addition, program descriptions and practices were extracted from publicly available information and reports and may have been outdated or not truly be reflective of the program in practice. Future research to apply this typology to more SP programs may expand our understanding of its applicability in other contexts. It would also be a useful exercise to survey a larger sample of existing SP programs to understand the current state of SP, and as time goes on, see if and how SP has evolved along the continuum.

A further limitation is that the SP field is expanding rapidly, and new hybrid models can be expected to develop over time. Through our updated search in December 2023, we found that the literature on SP has grown significantly in the past few years and while the typology of models remains robust, there will be a need to revisit it over time in future research.

A strength of this research is that the models developed through the academic literature search have been applied to existing SP programs, which offers support for their relevance in practice. Another strength is the endorsement of the results by the advisory council made up of community organizations.

6. Conclusion

When it comes to the question of which SP model to implement, we find that it may depend on the goals and motivations of implementers and decision-makers. Our research suggests a continuum of four different SP models: clinical, holistic, empowerment, and healthy community that encompass a variety of different SP programs seen in practice.

Our findings suggest that implementers have worked with the ambiguity of the term “SP” to create services that are unique to their contexts. Despite arguments in favor of clarity in policymaking to support implementation, our findings suggest that rather than being seen as a limiting factor, ambiguity has enabled flexibility and creativity in implementation that might have been restricted by a more rigid definition of SP. For this reason, our research proposes this concept of “bounded ambiguity,” which allows for flexibility and adaptation within set parameters that may facilitate the adoption and implementation of SP by policymakers, implementers, and researchers and help to ensure that the community-based and creative spirit of SP persists in its future.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

Funding

This research was funded by the Mitacs Accelerate Fellowship [69].

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted in partnership with United Way Halton-Hamilton. Preliminary findings of this research were presented at the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research Conference in May 2023 [70].

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.