Mapping Variation in Delivery Models and Data Recording of Primary Care Social Prescribing Link Worker (SPLW) Schemes Across Five Regions in England and Scotland

Abstract

Social prescribing link workers (SPLWs) connect people to community resources for better health and well-being. Over the past decade, SPLW schemes have expanded rapidly in NHS primary care in England and Scotland. However, how these schemes have been implemented and assessed in different parts of England and Scotland is not well understood. A mapping exercise of SPLW schemes in three English and two Scottish regions was undertaken to identify services and describe their key features, as well as any variations in delivery, what data are recorded, and how outcomes are measured. Consultations were held with SPLW stakeholders (n = 98) supplemented with online analysis. Using the TIDieR framework, a taxonomy of SPLW services was created. Across the five regions, four different SPLW employment models were identified, varying by employer and SPLW management approaches. Some regions used up to three models, others only one. Local variations in delivering SPLW schemes included different referral routes, age ranges, priority groups, types of SPLW schemes available, and number of sessions offered. A variety of methods were used to assess service user outcomes, including validated well-being tools, bespoke well-being tools, bespoke service user surveys, and qualitative case studies. Variation existed in data recording systems used and, in the frequency, and consistency in using assessment tools and recording service user outcomes. Variation in SPLW delivery models indicates regional and localized interpretations of SPLW schemes. Variations in recording and measuring service user outcomes and in well-being tools used present challenges for effective evaluation/s of each model and primary care SPLW schemes overall. Enhancing local and national data systems, along with supporting strategies and frameworks for evaluations, would boost SPLW infrastructure and support future policy developments.

1. Introduction

Internationally, primary care health services in high income countries are experiencing growing challenges as a result of aging populations, rising chronic illness and multimorbidity, persistent health inequalities, budgetary challenges, and the consequences of austerity policies [1–3]. In England and Scotland, concerns have been consistently raised about the capacity of NHS primary care services to address these growing pressures, particularly in light of growing postpandemic unmet need and workforce shortages [4–6].

England and Scotland have long-standing and growing health inequalities [7, 8], and for decades both countries have experienced an inverse care law, whereby the “availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served” [9, 10]. Consequently, new approaches to how primary care health services are organized to address these challenges are required and remain high on health policy agendas [11]. The last decade has witnessed an accelerated interest internationally in the concept of social prescribing, particularly in primary care [12–14].

Until relatively recently, there was no widely agreed definition of social prescribing; however, in 2023, a Delphi study involving an international multidisciplinary panel of experts and stakeholders agreed the following [15].

Social prescribing is “a means for trusted individuals in clinical and community settings to identify that a person has nonmedical, health-related social needs, and to subsequently connect them to nonclinical support and services within the community by co-producing a social prescription: a nonmedical prescription to improve health and well-being, and to strengthen community connections” ([15]; short definition).

1.1. Social Prescribing Link Working in English and Scottish Primary Care

Primary care policies in England and Scotland have promoted the use of social prescribing schemes and to enable this have funded the recruitment—at scale—of social prescribing link workers (SPLWs) [16, 17] to support GP practices to deliver social prescribing, supporting efforts to address social determinants of health. SPLWs work collaboratively across the health and care system and particularly with voluntary, community, and social enterprise (VCSE) organizations, to support service users referred to them.

In both countries, GPs and other primary care staff make referrals to SPLWs who, using a “good conversation” approach, meet service users and discuss what matters to them and what they need help with, and then make appropriate plans [18, 19]. Various methods of connecting service users to community social prescribing groups and activities are then used.

In England and Scotland, primary care health policy developments have been followed through into practice, with comprehensive SPLW schemes introduced and SPLW networks established in both countries.

1.2. The Development of SPLWs in England

Whilst both social prescribing services and link worker roles existed prior to the 2019 NHS Long-Term Plan [17], this policy delivered a significant development in social prescribing provision. Social prescribing was included as one of six programs in the comprehensive model of personalized care to promote enablement. NHS England recommended that social prescribing be targeted toward patients with chronic illness and multimorbidity, mild-moderate mental health conditions, patients with loneliness, and those with complex needs [17]. The 2019 Long-Term Plan provided funding for 1000 additional SPLWs to connect people to VCSEs, with a target that every GP practice in England would have access to SPLWs with a target of 900,000 people being referred into social prescribing schemes by 2023/24 [17].

In 2019, Primary Care Networks (PCNs) were introduced in England, groups of GP practices encouraged to work together, covering patient population groups of around 30–50,000. PCNs may directly employ SPLWs or subcontract provision of the service to another provider in accordance with the Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service (DES) contract specification. SPLWs are funded in PCNs as part of the England GP contract agreement to bring additional capacity to primary care [20–22]. In December 2023, there were over 3500 SPLWs in England [23] achieving the 2019 Long-Term Plan mandate for universal PCN coverage [24]. The 2023 NHS England long-term workforce plan reports intentions to increase this number to 9000 by 2036/37 ([25], p. 98).

In January 2023, NHS England produced the workforce development framework for social prescribing SPLWs [26], developed to support SPLWs and their employers to maximize impact of the role. Organizations employing SPLWs, including PCNs, can use this framework to support recruitment and retention. The framework also includes specific information for PCN SPLWs that are funded through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS), a program that provides funding to PCNs in England to recruit additional staff [26].

Alongside funding for SPLWs, in 2019, the English Department of Health and Social care provided £5 million [27] for the National Academy of Social Prescribing (NASP), a national charity to enhance social prescribing infrastructure [28]. England also has the National Association of Link Workers (NALW) [29], with over 1000 members who, whilst not a regulator, spearhead standards and advocate for social prescribing SPLWs in healthcare [30]. In 2019, NALW held its first SPLW conference [31].

1.3. The Development of SPLWs in Scotland

Following the introduction of devolution in 1999, health and social care policy was devolved in Scotland. In 2016, the Scottish Government (SG) produced a manifesto commitment to recruit up to 250 SPLWs to work in Scotland’s most deprived GP practices by 2021-2022 [32]. This followed a SG funded pilot study of SPLWs in socially deprived Glasgow GP practices in 2014 [33]; however, before the independent evaluation findings were published in 2017, the SG funded “early adopter” primary care–based SPLW schemes in five different areas of Scotland, across four separate health boards [34].

SPLWs were later formalized as one of six priority areas in the 2018 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) of the first ever Scottish GP contract which aimed to transform primary care in Scotland [35]. Following the new GP contract, funding and governance arrangements for SPLWs shifted centrally from the SG, to Scotland’s 31 Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs) [34]. HSCPs are organizations formed to integrate health and social care services provided by Scotland’s 14 Health Boards and 32 local authorities and came into effect following SG legislation in 2014 [36]. The SPLW programs were delivered as part of the SG’s Primary Care Improvement Plans (PCIPs) and mainly funded through the Primary Care Improvement Fund (PCIF) [34].

The 2018 Scottish GP contract MoU was later revised in July 2021 (MoU 2) [37] and whilst all six priorities of the original 2018 MoU remained areas of focus, HSCPs were encouraged to prioritize action on three of the six MoU areas, which did not include SPLWs (our emphasis) [37].

As of March 2024, there were 325 SPLWs in Scottish primary care [38]. Voluntary Health Scotland (VHS) is the national intermediary and network for voluntary health organizations in Scotland [39]. VHS advocates for the voluntary health sector in Scotland, collaborating with HSCPs, SG, universities, research bodies, and Royal Colleges to drive sustainable improvements in health and social care. Since 2021, the SG Primary Care Directorate has funded VHS to develop the Scottish Community Link Worker Network (SCLWN) to support Scottish SPLW infrastructure [40] and in 2023 the SCLWN held its first annual conference in Glasgow [41]. In 2020, the Scottish Social Prescribing Network (SSPN) was established to develop the strategic direction of social prescribing in Scotland [42] and in 2023 received funding from the SG. It works closely with the SCLWN and SG to develop social prescribing initiatives in Scotland.

In November 2023, Essential Connections, the first ever national scoping report of SPLW schemes in Scottish primary care, was published by VHS [43]. In relation to the changes in the GP contract MoU 2 (not prioritizing SPLWs) their report noted “This apparent diminution of community link working within the primary care improvement agenda was a significant worry among participants” [43, p37]. Similar concerns were also raised in a 2023 report by the SG’s Primary Care Health Inequalities Short-Life Working Group ([44], p5).

1.4. The Need for Reflection and Evaluation of Primary Care SPLW Schemes

The activities and outcomes of SPLWs at scale are a relatively new phenomenon in the English and Scottish primary care landscape and whilst having established SPLW networks in both countries, compared with other NHS primary care professional groups, the SPLW workforce is still in the early stages of development. However, systematic reviews on the impact of SPLW schemes both generally, and particularly in primary care, have suggested that the evidence base in this field is suboptimal and subject to bias [45, 46] and that high-quality evaluations are now required [47, 48].

Additionally, while one of the goals of SPLWs is to help address health inequalities by helping mitigate the effects of the social determinants of health, their actual long-term impact remains uncertain with some arguing that focusing on individual service user change without tackling systemic/structural factors could, inadvertently, widen health inequalities [49–52]. Furthermore, whilst it is recognized that more research is needed on SPLWs impact on health inequalities, research challenges include limited healthcare utilization data [53] and inconsistent data collection in general, but particularly on wider health determinants and ethnicity, which can result in an inability to fully explore SPLWs’ impact on health inequalities [54]. Questions remain about how SPLW outcomes are achieved within complex health systems [55], and the role of SPLWs in preventive healthcare has been underexplored [56]. Knowledge gaps persist regarding SPLW interventions on specific clinical conditions. A systematic review on social prescribing for mental health [57] found inconclusive results and recommended future research focus on theory-driven interventions, long-term outcomes, treatment fidelity, and person-centered care. Systematic reviews of social prescribing for long-term conditions [58] and on psychosocial referrals in primary care [59] highlight heterogeneous interventions, poor evidence quality, inadequate blinding, and high attrition, emphasizing the need for rigorous controlled trials to assess clinical relevance and sustainability.

Thus, to summarize, there are significant gaps in the evidence base for SPLWs in terms of effectiveness (both on service user outcomes and GP workload) and cost-effectiveness. In addition, there is a growing recognition that robust research and evaluation are required to better understand the key features of, and variations in, and efficiency of different SPLW delivery models, how they operate on the ground, and how effectively their impact on service users is being recorded and measured.

2. Multiregion and Multilevel Evaluation of SPLWs in English and Scottish Primary Care

The research reported here is part of a wider mixed methods evaluation of the roll out of SPLWs in English and Scottish primary care [60].

This part of the study covers three English regions, Greater Manchester, North East and North Cumbria, and West of England, and two Scottish regions, Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Lothian (see Table 1). The five regions are large and encompass multiple SPLW initiatives. These regions also provided sufficient variation in population age, gender and ethnicity, levels of socioeconomic deprivation, geographical location, and in distances to health and care services to understand how link worker services are organized and funded in different settings.

| Region | Population (approx.) | Description | Local health and care system(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIHR ARC Greater Manchester | 3.1 million | One of 15 ARCs across England supporting applied health and care research that responds to, and meets, the needs of local populations and local health and care system | Greater Manchester integrated care partnership https://gmintegratedcare.org.uk/nhs-gm/ |

| NIHR North East and North Cumbria | 3.1 million | One of 15 ARCs across England supporting applied health and care research that responds to, and meets, the needs of local populations and local health and care system | North East and North Cumbria integrated care partnership https://northeastnorthcumbria.nhs.uk |

| NIHR ARC West of England | 2.7 million | One of 15 ARCs across England supporting applied health and care research that responds to, and meets, the needs of local populations and local health and care system. Encompassing Bristol, North Somerset, South Gloucestershire, Gloucestershire, Bath, North East Somerset, Swindon, and Wiltshire |

|

| NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde | 1.3 million | NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde provides primary, community-based, and acute hospital services for the populations of Glasgow, Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, and Inverclyde | NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde https://www.nhsggc.scot/ |

| NHS Lothian | 910,000 | NHS Lothian provides primary, community-based, and acute hospital services for the populations of Edinburgh, Midlothian, East Lothian, and West Lothian | NHS Lothian https://www.nhslothian.scot/ |

This paper reports on the findings from work-package 1 of this study, the aim of which was to describe the key features and variations in delivery models for primary care–based SPLW schemes within and between each of the five research regions.

Determining the efficiency (including the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness) of different models of organization of link workers was not an aim of the current paper but will be explored in our ongoing NIHR funded program of research (of which this paper is a first output). This study was prospectively registered at Research Registry (ID: 8794) with relevant ethical approvals obtained from North East-York Research Ethics Committee (IRAS ID: 314870).

3. Methods

3.1. Mapping and Description of SPLW Schemes

To explore the background, development, and operational models of SPLW schemes in primary care, we gathered data through one-on-one discussions with key NHS primary care leads with responsibilities for SPLW activity and key VCSE stakeholders, as well as primary and secondary online sources across five research regions.

In each study region, we contacted the designated regional lead for person and community centered approaches (at Integrated Care Systems in England and HSCPs in Scotland) to help identify candidate services. We then contacted the designated lead for each identified candidate service to request insights and documentation relating to the development, organization, and delivery of the service.

We engaged 98 key SPLW stakeholders, including SPLW leads from PCNs, GP federations (England), and HSCPs, initially via email and then through follow-up meetings (in-person or online), to discuss the rollout and nature of SPLW services across each region. VCSE leads hosting/employing SPLWs in the five regions were similarly consulted. Using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [61] (described in Section 3.2) as a question guide, we conducted one-to-one discussions covering service background, development, funding, target groups, referral processes, and available community assets. Stakeholders provided reports, evaluations, and case studies to support our understanding and mapping of SPLW services.

In addition to these one-to-one meetings, we conducted online searches to gather detailed information on SPLW activities within PCNs, HSCPs, and VCSEs hosting/employing SPLWs. Google was the primary search tool used due to its extensive indexing, supplemented by VCSE network lists, charity directories, and health-focused VCSE organizational networks. Targeted phrases and keywords, such as “VCSE hosting/employing primary care link workers” and “voluntary sector link workers,” refined results. We reviewed official VCSE websites for evidence of link worker programs and community initiatives, and where direct evidence was scarce, job advertisements and press releases were analyzed for relevant insights.

Online searches faced challenges due to regional variations in link worker terminology (e.g., “community link workers,” “SPLWs,” and “community link practitioners”), requiring flexible search terms. Information gaps were common, especially for smaller VCSEs with limited or outdated online presence. To address this, search terms were refined iteratively, and supplementary sources like newsletters and reports were used to triangulate information.

Our systematic approach provided a structured framework to identify key SPLW leads across PCNs, GP federations (England), HSCPs, and VCSEs hosting/employing link workers. By engaging these leads, utilizing online resources, reviewing written materials, and applying the TIDieR template, we effectively mapped the development, funding, organization, and rollout of SPLW schemes in NHS primary care and VCSEs across five regions.

3.2. Mapping SPLW Activity Across 5 Regions Using TIDieR

Data gathering for the mapping exercise took place between April 2022 and May 2023.

The TIDieR [61] was used (see Supporting file 1: for our TIDieR template) to record the description of each local SPLW service across the five regions. The TIDieR is widely used in health research in a range of applied health research contexts and settings [62]. Detailed intervention description is important across many fields of health research, and TIDieR provides a standardized template to facilitate a detailed specification of the necessary components of any intervention or service, making it easier to delineate two or more similar interventions from one another.

The TIDieR template enabled us systematically describe SPLW services across the five regions, focusing on routine data availability, target groups, referral sources, scope of SPLW activities, service types (from “light” signposting to more “hands-on” therapeutic support), and appointment limits. The accuracy of the TIDieR descriptions was then sense-checked with the representatives from each identified service and the designated regional leads.

Using the completed TIDieR descriptions, we then developed a typology of service delivery models. Our core focus was on classification according to the type of service delivered, the populations targeted, and how the service was organized. The emergent typology of delivery models was then shared with stakeholders in order to check its overall representativeness. Stakeholders included local designated regional, our Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement Group and Research Advisory Groups, the NHSE national delivery team, and Public Health Scotland.

3.3. Data Analysis

Between September 2023 and July 2024, the researchers who conducted the mapping exercise across all five regions, authors ED, HC, CP, MB, ME, and HB, held regular formal meetings to agree on our methodological approach to analyzing the data, discuss ongoing analyses, discuss any differing opinions in interpreting the data, and refine our findings.

An inductive content analysis approach was used to examine the data collected in the TIDieR framework. The process was structured and descriptive. Initially, data were reviewed through each individual variable in the TIDieR framework, e.g., type of service provided, target population, and who refers to service, generating open codes. These codes were then grouped into categories, e.g., service user issues and supports offered to service users. Through constant comparison, the categories were synthesized into broader themes, e.g., collection of routine referral data, SPLW encounters, and service user outcomes, that identified common patterns and differences in how SPLW services were delivered on the ground. The analysis was iterative, ensuring findings remained grounded in the data and accounted for local and regional variations.

The TIDieR framework data were then organized manually in Microsoft Word using tidy data principles [63]. Although developed for quantitative data, this structured approach suited multiple qualitative data descriptions of SPLW interventions collected across five regions. Each variable (e.g., referral processes, target populations, and outcome data) was placed in a column, each observational description in a row, and additional detail in a separate cell. This format supported inductive content analysis, enabled systematic comparison, and once data were categorized allowed for broader thematic summations. Analyzing these structured data was manageable without software, and the use of a consistent tool like the TIDieR template proved effective for this structured and descriptive exercise (see Supporting File 1 for a copy of our TIDieR template).

We conducted separate in-depth analyses in each of the five regions to identify key features of SPLW services, producing regional summaries of how schemes were centrally organized and delivered in practice. These were then aggregated for cross-regional comparisons, allowing us to identify commonalities and differences in delivery models. Regular analysis discussions helped refine findings and informed the development of a visual model of SPLW service typologies, which, together with the regional summaries, captured key areas of variation and convergence at scale, including SPLW service types, target populations, referral processes, scope of support, service monitoring, and outcome data collection.

4. Results

4.1. SPLW Service Model Typology

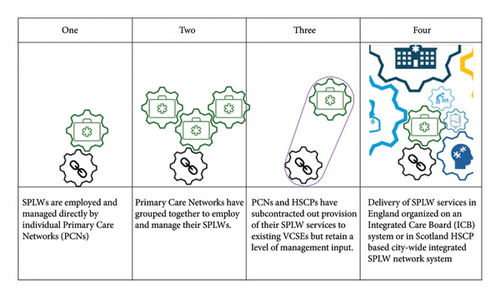

The SPLW schemes examined in the five regions covered 143 PCNs (in three English regions) and 10 HSCPs (in two Scottish regions). We identified four different model types regarding service delivery of SPLW services in primary care.

The models of service arrangement in use across the five regions are summarized and illustrated in Figure 1.

The following sections also provide a description of the model types; the different models in operation; variation in model usage; priority groups for whom the SPLW schemes were targeted; referral sources to SPLW schemes; and the scope of SPLW services provided and describe the collection of routine referral data, SPLW encounters, and service user outcomes across the five research regions.

4.1.1. Description of Models

- •

Model 1: SPLWs operated under the direct employment and line management of their respective PCNs. Under this management model, SPLWs receive their social prescribing training and report to designated line managers within the PCN, typically a senior staff member, such as a PCN manager or a dedicated PCN SPLW coordinator, who oversees their day-to-day activities and provides guidance and support, in line with that PCN’s SPLW aims and objectives.

- •

Model 2: A group of PCNs has partnered together to manage, oversee, and employ their SPLWs. This typically involves collaboration between multiple PCNs within a region or locality to pool resources, share expertise, and create efficiencies in the delivery of social prescribing services. In a grouping of PCNs, the management of SPLWs may be centralized under a lead manager or social prescribing coordinator who oversees the SPLWs across the grouped PCN, oversees their day-to-day activities, and provides guidance and support, in line with that PCN’s SPLW aims and objectives.

- •

Model 3: PCNs and HSCPs outsourced SPLW services to VCSEs, who were commissioned to employ SPLWs and provide SPLW services, whilst also retaining a degree of management input regarding SPLW training, support, and oversight of core SPLW activities. In England, PCNs worked with VCSEs to deliver SPLW services while maintaining management oversight to ensure quality and effectiveness. In Scotland, HSCPs have an SPLW lead responsible for overseeing SPLW services, ensuring alignment with local health priorities, and coordinate with VCSE leads commissioned to provide SPLW services and who handle day-to-day SPLW management. The HSCPs collaborate with VCSEs in providing training and development for SPLWs, covering essential social prescribing practices, health and social care policies, and other essential areas to provide social prescribing support to service users.

- •

Model 4: A more integrated system operates. In one of the English regions (South West), an integrated care board (ICB) plays a strategic role in commissioning, with funding split between the county council (one-third) and the NHS (two-thirds). The ICB commissions community social prescribers, certain community services for patient referrals, and provides support and training for SPLWs, including social prescribing ambassadors. SPLWs are funded, employed, managed, and hosted either by PCNs or a VCSE, except for two PCNs using ICB-funded community social prescribers hosted by VCSE providers instead of ARRS-funded link workers. In Scotland, in the one HSCP in Lothian that aligned with Model 4, the HSCP, in partnership with a voluntary sector organizations council, established a city-wide SPLW Network to oversee SPLW activity, providing training and line management support to SPLWs. VCSEs that employed SPLWs also contributed to SPLW management. The city-wide HSCP SPLW network managers regularly coordinated with VCSE leads hosting SPLWs and GP surgeries housing them, using a matrix system involving HSCP, VCSE, and GP leads to guide SPLW activity. Regular meetings were held between VCSE leads hosting SPLWs, GP leads, and city-wide HSCP SPLW network managers to review referral data and service user outcomes.

In essence, the four models differ in employment arrangements, management structure, and the degree of formal collaboration through commissioning between PCNs, HSCPs, and VCSEs, and, in one English region, strategic bodies such as ICBs.

4.1.2. Different Models in Operation Across the Five Research Regions

Across the five regions, apart from Greater Glasgow and Clyde, there was diversity in the number of models that were adopted. Additionally, whilst each region shared many commonalities in adopting similar models, there was diversity both across and within the five regions in terms of the priority groups targeted by the SPLW schemes, the sources of referrals to these schemes, and the range of services provided by SPLWs.

In the 5 research regions, four regions operated a mixture of service model types. In England, all three regions saw three different model types in operation. Greater Manchester and North East and North Cumbria used Models 1, 2, and 3, whilst the West of England used Models 1, 3, and 4. In Scotland, one region, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, all 6 HSCPs used Model 3. In the other region, Lothian, Models 3 and 4 were operated.

Of the SPLW models in operation, Model 3 was by far the most common in PCNs and HSCPs. In England, 98 of the 143 PCNs mapped used Model 3. In Scotland, nine out of 10 HSCPs mapped used Model 3.

In one of the English regions, Greater Manchester, three PCNs originally used a different model to provide SPLW services, two in a group with other PCNs used Model 2, and one PCN initially used Model 3 but ultimately the PCNs decided to manage the service themselves and adopted Model 1. Two PCNs gave a justification for providing the service in this way, one saying that it gave them more “ownership” of the SPLW role and the other that it gave them more “control” over the SPLW role and that it promoted better teamwork between the SPLW and the wider primary care team. Of the models in use in the 5 research regions, the specific breakdown was as follows (Algorithm 1).

-

Algorithm 1: Different models in operation across the five research regions.

-

Greater Manchester

-

Of 64 PCNs examined, 6 used Model 1, 18 used Model 2, and 40 in Greater Manchester operated under Model 3.

-

West of England

-

Of the PCNs mapped, 8 used Model 1, none used Model 2, and 24 used Model 3. In one ICB-led locality, funding (NHS: two-thirds, council: one-third) supports SPLWs hosted by PCNs or third parties. Two PCNs used ICB-funded, third-sector-employed SPLWs (Model 4).

-

North East and North Cumbria

-

Of 41 PCNs examined, 5 used Model 1, two used Model 2, and in the remaining PCNs, Model 3 operated.

-

Greater Glasgow and Clyde

-

All six HSCPs use Model 3.

-

Lothian

-

Three HSCPs use Model 3. The largest HSCP operated Model 4.

4.2. Variation in Model Usage Across the Five Regions

- •

Model 1

-

Greater Manchester, North East and North Cumbria, and West of England PCNs implemented ARRS-funded social prescribing models. Greater Manchester transitioned to in-house management for better control and teamwork. North East and North Cumbria supplemented existing services reactively, while the West of England tailored this modeled approach to specific community needs, varying referral pathways and support levels.

- •

Model 2

-

Greater Manchester and North East and North Cumbria regions use GP Federations and Alliances for SPLWs, with some predating ARRS funding. Services, primarily ARRS-funded, focus on primary care referrals, with limited outcomes data. Greater Manchester’s Federations and Alliance manage SPLWs for multiple PCNs, while North East and North Cumbria prioritizes locally chosen or generic social prescribing services.

- •

Model 3

-

Model 3 implementation varies across five regions. In Greater Manchester, 40 PCNs subcontract SPLWs to 10 VCSEs, with some services borough-wide or supporting multiple PCNs, all collecting outcome data. North East and North Cumbria use single or multiple contracts through GP federations or PCNs, offering mostly generic services with some targeting specific needs. In the West of England, PCNs employ ARRS-funded SPLWs hosted by VCSEs, with services differing by area, ranging from unlimited sessions in deprived regions to waiting times elsewhere. In Greater Glasgow and Clyde, six HSCPs commission varying VCSEs with each SPLW delivery reflecting their history, with the largest HSCP initially having two VCSEs before consolidating to one. Lothian’s Model 3 involves no self-referrals and only NHS primary care referrals, with the number of VCSEs and SPLW locations varying by HSCP, such as specific GP practices or community well-being hubs.

- •

Model 4

-

In the one English region operating Model 4, social prescribing is commissioned at an ICB level whilst being hosted and funded at a PCN level through ARRS and ICB/local authority funds. The PCNs using this model share similarities in their aims of providing personalized support to individuals based on their needs, leveraging partnerships with various stakeholders including PCNs, charities, councils, and VCSEs. However, differences did arise in their host organizations, funding sources, target populations, referral processes, and data management approaches.

For greater detail regarding the extent of variation within the models across the regions, see Supporting Table 1: Use, and variation of use, of each service model in and across five regions.

4.3. Priority Groups for Whom the SPLW Schemes Were Targeted

Across the five regions priority groups covered included a very broad range of service user types and needs, covering all population types. In some of the regions, North East and North Cumbria, West of England, and Greater Glasgow and Clyde, PCNs and HSCPs offered services to all age groups, catering for children and young people. In other regions, Greater Manchester and Lothian, PCNs and HSCPs focused on adults only.

In some regions, as well as offering generic SPLW services some PCNs and HSCPs offered more specialist SPLW service support. In North East and North Cumbria, some PCNs operating Model 3 services could choose target population groups if they wished and other SPLW services designed specifically for a target population or need such as mental health support, learning disabilities, or children services. In the West of England, some SPLW services began as focused, i.e., over 50s, those leaving hospital, those with mental support needs, those at risk of frailty, and those who have complicated health needs related to the challenges they face living in a deprived area. However, most reports indicate that those currently being referred have a broader range of needs. In Greater Glasgow and Clyde, some HSCPs, whilst offering generic SPLW services, also had two thematic SPLWs that focused on asylum seekers and refugees and homeless people.

In Greater Manchester and Lothian, the SPLW services across PCNS and HSCPs did not offer such specialist supports, and instead offered a broad generic service to all types of service users (although in Greater Manchester one SPLW service targets those aged over 50 years and in one Lothian HSCP a SPLW was based in a service to support people experiencing homelessness).

In some regions, such as Lothian, for example, services were adapted over time with one HSCP, which was an early adopter of SPLW services in Scotland in 2017, and the target population was initially weighted to address populations experiencing social deprivation and experiencing/at risk of health inequalities but since the introduction of the 2018 Scottish GP contract, there are now almost equal numbers of mainstream and health inequalities focused SPLWs.

A brief summary of each region’s target groups is provided below (Algorithm 2).

-

Algorithm 2: Summary of priority groups for whom the SPLW schemes were targeted.

-

Greater Manchester

-

Models 1 and 2 offered SPLW services to all adults, with no specific targeting. Model 3 also targeted all adults, except for one SPLW focused on those 50 and over.

-

West of England

-

SPLW services mostly targeted adults, with some including children. Early schemes focused on specific groups, e.g., frailty and over 50s, but current referrals are broader. Model 1 tailored services to community needs, while Model 3 included children’s services and adapted to local resources. Specialist services supported hospital discharge and high-intensity ED users.

-

North East and North Cumbria

-

Most SPLW services focused on adults, some including children or families. Model 1 complemented local services, Model 2 allowed PCNs to select priority groups, and Model 3 focused on specific groups like mental health or children’s services or let PCNs choose targets.

-

Lothian

-

Introduced in Lothian’s largest HSCP in 2017, SPLWs initially targeted deprived populations. This focus continues, with broader adult referrals, including nondeprived. Since the 2018 GP contract, services balance mainstream and health inequality focus, targeting only adults in Models 3 and 4.

-

Greater Glasgow and Clyde

-

SPLWs were introduced in 2014 in deprived GP practices, expanding to two HSCPs in 2017, targeting health inequalities. This focus continues across all six HSCPs, with nondeprived populations also eligible. The largest HSCP’s main VCSE worked with children, families, and self-referrals, while another offered specialist services for asylum seekers, refugees, and homeless people.

4.4. Referral Sources to SPLW Schemes

Across all the five regions, most referral sources came from staff employed in GP practices which SPLWs were allocated to. In all the regions, all GP practice staff, including receptionists, could make referrals to SPLWs. In four out of the five regions, self-referrals were also accepted, with only Lothian certifying that referrals had to come from GP practice staff.

In two English regions, additional referral sources to self and GP practice staff referrals included referrals from a range of nonprimary care services. These included, in Greater Manchester, in small numbers, referrals from the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Ambulance service and in South West England, referrals from a range of health/social/community care services. In Scotland, of the HSCPs mapped, all referrals were either by GP practice staff only (Lothian) or self-referral and GP practice staff (Greater Glasgow and Clyde).

A brief summary of each region’s referral sources is included below (Algorithm 3).

-

Algorithm 3: Referral sources to SPLW schemes.

-

Greater Manchester

-

Across all three models that operate, most referrals come from primary care staff, particularly GPs. Self-referrals were also supported. Other referral routes (small numbers) included Ambulance Service, adult social care, and the DWP.

-

West of England

-

Referrals were mainly from GP practice staff though there were some examples of referrals from other health/social/community care services and also self-referrals from service users.

-

North East and North Cumbria

-

Some SPLW schemes restricted referrals to GPs, while most allowed any GP staff, self-referrals, or external organizations. Many also permitted rereferrals, especially for time-limited services.

-

Lothian

-

All referrals were from a wide range of GP practice staff (including reception staff). No self-referrals.

-

Greater Glasgow and Clyde

-

Referrals were from a wide range of GP surgery staff and in most HSCPs service users could also self-refer.

4.5. The Scope of SPLW Services Provided

The scope and nature of SPLW services provided across the five regions were numerous and wide-ranging but there was a commonality across the regions regarding key issues service users needed support with, and supports offered to service users, as outlined in Table 2.

| Services user issues | Supports offered to service users |

|---|---|

|

|

Some SPLW schemes in the five regions had exclusion criteria, e.g., service users currently receiving support from psychiatric services, or with known behavioral issues, suicidal ideation, acute psychoses or those in current or very recent crisis, or housebound. However, in some regions, SPLWs did make home visits to housebound service users.

The heterogeneity of SPLW schemes offered reflected the enormous diversity of service user needs, and also the different levels of engagement service users needed with SPLWs. Some service users required only one session with a SPLW to address a single immediate issue (e.g., signposting to weight management support or a grant to purchase a much-needed domestic appliance). Other service users, particularly those with complex psychosocial needs, required longer-term, more therapeutic support for numerous and/or more complex issues over a number of sessions (e.g., someone living with a number of life-limiting chronic illnesses including depression, very socially isolated, and wishing to make lifestyle changes).

Across all the regions and models, SPLW services offered signposting to appropriate VCSE community services and help in managing issues that require support from statutory services such as housing and benefits through local authorities and the DWP. Across all five regions, SPLW services also offered support to service users in accessing support for core social determinants of health, for example, support in addressing food and fuel poverty, help in purchasing much needed household goods, and help with debt. For many service users with complex psychosocial needs, the therapeutic support provided by SPLWs was very important.

4.5.1. Variation in SPLW Session Supports for Service Users

Great variation existed across the five regions and within the regions across PCNs and HSCPs in the length of time that service users were supported. Across all the regions, some SPLW services in PCNs and HSCPs offered extended ongoing support to service users with no limit in the number of sessions offered. Some PCNs and HSCPs had a policy of limiting sessions with service users, which were typically 4–6. This meant that in Scotland, for example, in both regions, one HSCP offered longer term ongoing support, whereas other HSCPs in the same region had a policy of limiting sessions. This variation in sessions also occurred across all the English regions and across PCNs.

In some PCNs and HSCPs, SPLWs were more hands on at accompanying service users to attend the first meeting of a VCSE group, whereas in other HSCPs and PCNs, this was often deemed to be a last resort.

A very broad summary of each regions scope of service provision is provided below (Algorithm 4).

-

Algorithm 4: Scope of service provision.

-

Greater Manchester

-

SPLW services provided vary but all connect users to local VCSE groups and relevant community and statutory services through signposting or referrals, sometimes accompanying them. Support sessions are often time-limited, with durations varying by need or borough. Rereferrals are allowed if needed.

-

North East and North Cumbria

-

Link worker services range from signposting to longer-term support, with flexibility based on user needs. Service limits vary, often three to six sessions. Some SPLWs accompany clients to VCSEs if extra support is needed.

-

West of England

-

The scope of link worker services ranged widely from signposting to longer term support. Some PCNs put a cap on number of visits (often six) but in other PCNs, SPLWs can continue seeing service users until they no longer need any more support or all possible services have been saturated; in certain areas, the number of sessions offered to service users can be dependent on need.

-

Lothian

-

SPLW services range from signposting to longer-term support, typically limited to four to six sessions, though one HSCP allows 10+. Most HSCPs permit service users to return later as rereferrals but some have a time cap. SPLWs may accompany clients to initial VCSE meetings if needed.

-

Greater Glasgow and Clyde

-

The scope of service varies across HSCPs. Some HSCPs use a 4-session model but would not discharge a service user if deemed at risk. The largest HSCP tailors support to user needs, with some HSCPs using a 4-session model but retaining at-risk users. Services range from signposting to group therapy and may include joint or accompanied appointments, e.g., PIP assessments.

4.6. Collection of Routine Referral Data, SPLW Encounters, and Service User Outcomes

As highlighted in Table 3, there was significant variation in link worker data collection both across and within regions, as well as among individual PCNs and HSCPs, in terms of systems used, data collected, and outcome measures used and how consistently.

| Region | Data collection system used | Data recorded | Outcome measures used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Manchester | Some SPLW services used Elemental or “simply connect” or developed their own databases. | All services collected some data on referrals and encounters including referral numbers, age, gender, ethnicity, reason for referral, nature of appointments (face-to-face/telephone), and length of appointments, where a service user was signposted. Some services also monitored number of service users waiting/active/discharged. | Model 1 services did not routinely collect outcome data, except for sporadic use of ONS4. Model 2 services occasionally used ONS4. All Model 3 services collected some outcome data, but there was significant variety in how systematically this was done. |

| North East and North Cumbria | The software system’s EMIS and SystmOne are routinely used, with some services also using DCRS and CharityLog. A few SPLW services adopting Model 3 developed bespoke databases. | Basic referral data collected on referrals including referral numbers, age, gender, ethnicity, reason for referral, nature of appointments (face-to-face/telephone), and length of appointments, where a service user was signposted. |

|

| West of England | Referrals and encounters were generally recorded in EMIS, SystmOne, or Elemental. Some SPLW services used own spreadsheets to manually record referral data. | Basic referral data collected including demographic details of service users, source of referrals, type of support required, and waiting times. |

|

| Lothian |

|

|

|

| Greater Glasgow and Clyde |

|

In the largest HSCP data recorded/collected include numbers of referrals, dates of referrals, number of encounters, demographic details, and equalities monitoring data. In the other HSCPs, data recorded include demographic details, number of referrals, dates of referrals, number of encounters and equalities monitoring data |

|

Data systems include widely used platforms such as EMIS, SystmOne, Elemental, and bespoke databases, with some regions using additional tools like NEBULA, CharityLog, or Salesforce. Data collected commonly cover referrals (numbers, demographics, and reasons), appointment details, signposting, and service user statuses. In some regions, PCNs and HSCPs also gathered general outcomes data, financial gains, or patient feedback. Outcome measures varied, with ONS4 and (S)WEMWBS being the most frequently used tools, supplemented by others like Well-Being Star, PAM, Recovery Outcomes Web, and bespoke assessments. Regions differed in consistency and quality of data collection, with some HSCPs producing detailed annual reports while other PCNs and HSCPs collected data more sporadically.

For additional information, including routine data collected, see Supporting Table 2: Additional information about SPLW schemes in the five regions.

Feedback from some key stakeholders involved in the mapping exercise highlighted some SPLWs concerns over using validated well-being tools to measure service user outcomes with some feeling that well-being tools such as ONS4 and WEMWEBS did not appropriately capture social prescribing interventions, especially the frequently reported “softer” impact SPLW interventions can have on service users.

5. Discussion

This mapping exercise aimed to explore what the key features and variations in delivery models were for primary care–based social prescribing SPLW schemes within and between each of our five research regions.

We identified four different employment models of SPLW schemes relating to who employed and managed SPLWs across the five regions. Some regions operated up to three different model types, with some only using one. Local variations in delivering SPLW schemes included different referral routes, age ranges covered, priority groups, types of SPLW schemes available, and number of sessions offered.

Model 3, where PCNs/HSCPs subcontracted SPLW services to existing VCSEs, was the most popular in English and Scottish regions. Its key advantage is the SPLWs’ close connection to VCSEs and community resources, fostering links, relationships, and referral pathways, highlighting the importance of local resources and partner organizations in delivering social prescribing. Model 4 also subcontracted SPLW services to VCSEs but used a more integrated management system to oversee SPLW services.

Across all five regions, the needs of service users and the intensity of SPLW involvement varied significantly. Some service users required minimal “light” signposting support after a single session to address an immediate practical issue (e.g., help with weight management and dietary advice or help with food/fuel poverty). Others needed longer-term, more therapeutic support over numerous sessions (e.g., a service user living with life-limiting chronic illnesses, experiencing depression, socially isolated, and wanting to make lifestyle changes to “feel better”).

In one region, a lead SPLW stakeholder in an HSCP described their SPLW service scope as “in the middle of a spectrum between light signposting and intensive support service.” This heterogeneity, and the variation in SPLW input required, poses challenges for impact evaluations of the different delivery models and SPLW working overall, as others have highlighted [64, 65].

Each of the five regions had different data requirements, which also varied across PCNs and HSCPs within the same region. There was diversity in the systems used to collect, record, and monitor service user engagements and in the frequency, robustness, and consistency of recording and measuring service user outcomes. This also applied to well-being tools used to assess outcomes. Such diversity presents challenges in evaluating social prescribing SPLW schemes, something noted in previous studies of SPLWs in Scotland [43] and England [64, 65].

Two of the most commonly used well-being tools were ONS4 and WEMWBS. The ONS4 uses four 0-10 scale questions on life satisfaction, purpose, happiness, and anxiety to provide a widely used snapshot of personal well-being for research and policy. The WEMWBS (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale) measures mental well-being through 14 positive statements rated on a one to five scale, covering thoughts, feelings, and functioning. A shorter version of this tool, (S)WEMWBS, uses 7 statements. Some stakeholders in the mapping exercise noted concerns from some SPLWs about using validated well-being tools (e.g., ONS4 and WEMWBS), which they found inappropriate in capturing service users’ experiences of social prescribing and engaging with SPLWs.

In response, some SPLW services developed their own local, nonvalidated tools, patient surveys, and qualitative case studies to assess outcomes. Systematic reviews of social prescribing schemes report a limited evidence base [46] and our findings would agree that there is an urgent need for agreed validated outcome measures and increased evidence base [47].

However, as others have recognized [65, 66], defining standard outcome sets for wide-ranging social needs is challenging. To address the question, “What is the best way to evaluate social prescribing?” Ayorinde et al. [65] conducted a qualitative feasibility assessment for a potential national impact evaluation study in England. Participants had mixed views on the ideal outcomes to be measured for evaluating SPLW interventions, noting that some of the evaluation options considered were more suited for very defined medical conditions.

Sandhu et al. [67] argue that since social prescribing involves a complex array of interventions spanning numerous agencies, spread widely over time and place, a mix of methods is needed to understand how these interventions are applied in real-world settings, who benefits, how intended outcomes are achieved, and how outcomes differ by context.

Despite these challenges, as others have argued [68–70], developing standardized evaluation frameworks with common metrics would allow consistent assessment of the benefits of SPLW interventions and enable comparisons across different sites and different SPLW models.

Finally, across all five regions, SPLW schemes strongly relied on VCSE groups to meet diverse service user needs, emphasizing the need for SPLWs to maintain good relations and continually update local VCSE capacity. As reported elsewhere [71, 72], our mapping highlighted financial uncertainties for VCSEs given cuts to services, and as previous studies have noted [33, 64, 65], this can be a barrier to effective SPLW interventions.

6. Implications for Policy and Practice

To progress the practice and evaluation of SPLW schemes, there is a need to better define the scope of interventions and identify the specific outcomes they seek to accomplish.

Future studies should provide detailed descriptions of SPLW interventions and their implementation to allow for meaningful comparisons across various service user populations, contexts, and health and well-being statuses.

Better understanding is required around the effectiveness of “light-touch” versus more intensive therapeutic SPLW interventions. Program management should help SPLWs track interaction data to enable research on how different levels of support impact outcomes.

Future research should compare the different SPLW delivery models to assess their overall strengths and weaknesses, their impact on service users, their effectiveness in supporting SPLWs, how effectively they use data for service improvement, and their plans for SPLW sustainability.

Future studies should consider how to develop validated well-being tools that capture the key aims and outcomes of social prescribing intervention/s.

Future evaluation frameworks should include the perspectives of service users, primary care practitioners, service providers, VCSEs, and SPLWs to optimize intervention components.

Engaging with the broader primary care SPLW community is crucial to ensuring that future impact evaluations are feasible and do not add extra strain on an already pressured workforce.

7. Strengths and Limitations

7.1. Limitations

In some of the regions, the number of PCNs examined in the mapping exercise was fewer than the exact number of PCNs in operation.

Some reporting may have been inaccurate if researchers’ summaries of the SPLW interventions varied from the actual implementation and adaptations led by practitioners.

Because SPLW schemes are developed and implemented differently in various regions across different UK countries, the results of this mapping exercise may be relevant only to regions with similar SPLW models.

7.2. Strengths

The five regions are diverse, covering multiple SPLW schemes and varying in population demographics, socioeconomic factors, geography, and access to services, offering insight into different organizational and funding approaches to primary care SPLW services.

In-depth consultations (n = 98) were organized with key stakeholders representing appropriate NHS, local authority, and VCSEs involved in the management and delivery of primary care SPLW schemes.

We used the TIDieR to provide a full description of SPLW services in the five regions, including the additional item of “voice”, i.e., who was involved in preparing the description. The accuracy of the TIDieR descriptions was sense-checked with key stakeholders.

8. Conclusions

Policy support for primary care SPLW schemes in England and Scotland has advanced more rapidly than available evidence of their effectiveness, with insufficient guidance and data infrastructure to evaluate different models and their respective effectiveness across wide-ranging service user needs. Variation in SPLW employment models indicates regional and localized interpretations of how to deliver SPLW schemes.

Stronger evaluations of SPLW models are needed, especially for assessing outcomes. This requires consistent use of validated well-being tools, though their ability to capture key components of social prescribing interventions should be considered.

Strengthening local and national data systems, with supporting evaluation strategies and frameworks, would improve infrastructure and aid future policy development.

As explained earlier, there is also a gap in our knowledge of the efficiency of different models of SPLW organization and employment, which was not an aim of the current paper, but will be reported in future papers from our ongoing funded program of work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (grant award ID NIHR134066).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the SPLW stakeholders for meeting with the study’s research fellows across the five research regions.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.