Moderating Effects of Age on the Longitudinal Associations Between IADL Disability, Self-Rated Health, and Depression Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults

Abstract

Background: The potential association and underlying mechanisms between instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and depressive symptoms in middle- and older-aged adults remain unclear. This study explores the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms among Chinese middle-aged and older adults and examines the mediating or moderating effects of self-rated health (SRH) and age on this relationship.

Methods: We used data from five waves (2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020) of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative survey. A total of 4830 participants aged 45 and older were included in the analysis. Longitudinal associations between IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms were tested using cross-lagged models to simultaneously evaluate the bidirectional association and the strength of the temporal association.

Results: Among middle-aged and older adults, there was a significant bidirectional longitudinal relationship between IADL disabilities and depressive symptoms. Higher levels of IADL disability predicted an increased risk of depressive symptoms and vice versa. SRH mediated the bidirectional relationship between IADL disabilities and depressive symptoms. Higher levels of IADL disability led to lower SRH, which further increased the risk of depressive symptoms and vice versa. Age moderated the cross-lagged models, indicating that the effect of SRH on the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms was stronger in the middle-aged group than that in the older group.

Conclusion: The study results clarified the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults. Healthcare providers can use the findings to design targeted interventions to address the decline in IADL function and potentially benefit mental health. Helping middle-aged and older adults improve their SRH may interrupt the vicious cycle linking IADL disability and depressive symptoms, particularly in middle-aged adults transitioning to old age.

1. Introduction

Older adults are becoming the fastest growing segment of the global population. Population aging poses significant challenges to society, and depression is one of the most common mood disorders among older adults. Depression is associated with poor quality of life and increased morbidity, disability, and mortality [1]; thus, it contributes significantly to the global burden of disease [2]. Over the past decade, the number of people with depression has increased by approximately 18%, and the incidence of depression increases with age [3]. In China, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults has reached 24.1% [3]. The disease burden of depressive symptoms has been increasing as well and is expected to increase annually in the future [4].

Many studies have shown that functional impairment and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults are related [5]. Activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) are two primary components of functional impairment that reflect the incidence of diseases and the cumulative effects of the aging process [6, 7]. Current research has confirmed that they are significant risk factors for depression. The prevalence of IADL disability is high and usually precedes that of ADL disability [8, 9]. IADL disability refers to activities that support daily life within the home and community and typically require more complex interactions. Focusing on and maintaining the IADL of middle-aged and older adults is the foundation of independent living and participation in community activities, which are crucial for reducing the potential caregiving burden on families and society. Although evidence links ADL disability with depression in older adults, research that explicitly focuses on the relationship between IADL disability and depression remains insufficient.

The relationship between IADL and depressive symptoms in older adults is complex and bidirectional [10]. Studies have shown that older adults with poor IADL report significantly more depressive symptoms [11, 12]. Beck’s cognitive theoretical model of depression explains the possible bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms [13]. Individuals at risk for depression develop dysfunctional attitudes and negative beliefs, ultimately leading to physical illnesses, including ADL disabilities. These symptoms result in negative cognition, creating a vicious cycle [14]. From the social participation perspective, IADL disability reduces social participation and weakens emotional support by decreasing the sense of control over life and interfering with independent living, which in turn lead to negative emotions and the risk of depression [15, 16]. Regarding psychological aspects, when middle-aged or older adults are unable to perform IADL because of physical limitations, they may feel isolated and helpless, which can increase the occurrence of depressive symptoms. Conversely, depressive symptoms can lead to a further decline in IADL by weakening physical and mental functioning [17]. However, most studies have only confirmed the unidirectional longitudinal association between IADL disability and depressive symptoms, while evidence for the bidirectional association between the two is still lacking. Furthermore, few studies have empirically validated the potential mechanisms underlying the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms.

From a self-concept perspective, self-rated health (SRH) is conceptualized as a stable perception of personal health goals and motivations that influence disease risk over time [18]. Older adults with higher SRH tend to adopt proactive strategies to cope with health issues [19]. SRH is an essential predictor of IADL disability and depression in older adults [20, 21]. Longitudinal studies have suggested that poor SRH is significantly associated with functional decline, and improvements in functional disability can improve SRH [22, 23]. Cross-sectional studies have indicated that older adults with depression are more likely to have poorer SRH, and improving SRH may in turn help prevent depression [21, 24]. Most studies have focused on the longitudinal relationship between SRH and depression, showing that SRH can predict the development of depression [25]. A meta-analysis showed that poor SRH among older adults was a significant risk factor for developing depression [26]. Therefore, owing to its bidirectional association with disability and depressive symptoms, SRH may be a crucial mechanism in the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms.

Kiyoshige et al. [17] reported that the association between depressive symptoms and a decline in IADL ability shows significant differences in the 70–80-year age group only. This suggests that the impact of depressive symptoms on IADL disability may vary with age, possibly because of differences in physical and psychological states across age groups. Some studies indicate that the relationship between SRH and IADL disability does not vary with gender but does so with age or depression status [20]. A previous study shows that the association between SRH and depression is more significant in the “preretirement” age group (50–64 years) and the “young-old” group (65–79 years) but weaker in the “old-old” group (80 years and above) [27]. Another study suggests that the strength of the relationship between SRH and mental health did not increase with age [28]. A study on the conceptual model of SRH provides evidence that SRH does not decline with age: it may remain unchanged even if health deteriorates [29]. In addition, older adults tend to provide more positive assessments of their health status than do middle-aged adults [30]. Therefore, age may play a role in moderating the bidirectional associations between IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms. However, current studies have mostly examined the impact of age on the relationship between disability and depression, but there is still a lack of research on how age simultaneously influences the relationships among the three variables.

In the context of China’s aging population, IADL disabilities and depressive symptoms pose challenges for social work and public health. In explaining the causal relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms, longitudinal studies are mostly limited to unidirectional relationships, and few have explored the potential mechanisms between the two. Therefore, in this study, a sample of middle-aged and older adults from China was used to verify the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms, as well as the impact of SRH and age on their relationship.

In summary, this study aimed to (1) explore the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms using five waves of longitudinal data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) through cross-lagged panel models; (2) investigate the longitudinal mediating role of SRH in the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms; and (3) examine the longitudinal associations between IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms across different age groups, thereby verifying the moderating effect of age.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

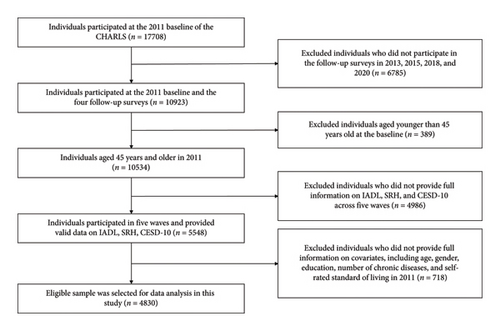

The database used in this study is the CHARLS. This nationally representative longitudinal survey provides high-quality data from middle-aged and older Chinese adults on a wide range of information, including socioeconomic status and health conditions. The CHARLS has a large sample size and wide coverage and uses a multistage, stratified probability proportional to the size (PPS) random sampling method. It includes residents from 150 counties and 450 villages in 28 provinces in China. The baseline survey was conducted in 2011 and included 17,708 individuals, with a response rate of 80.51%. Four follow-up surveys were conducted with 18,264, 20,284, 17,970, and 19,367 individuals, respectively. The current study used the CHARLS survey from 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2020. For each wave, we selected participants aged 45 years or older with no missing answers to the questions on depressive symptoms, SRH, IADL disability, age, gender, education, self-rated standard of living, and number of chronic diseases. Finally, 4830 participants were selected through ID matching (Figure 1). Among them, 4265 participants were middle-aged adults (less than 65 years) and the rest were older adults (n = 565).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. SRH

SRH status is widely used in health studies [31]. Participants were asked, “Would you say your health is very good, good, fair, poor, or very poor?” The responses were scored on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor). Higher scores indicated poorer health status.

2.2.2. Functional Disability (IADL)

Functional disability was measured based on the number of physical limitations in performing IADL. Well-trained interviewers asked participants whether they experienced difficulty performing any of the five IADLs (doing housework, preparing hot meals, shopping, handling finances, and taking medications) [32]. The four response items were (1) I do it without any difficulty, (2) I can still do it despite difficulty, (3) I have difficulty and need others’ help, and (4) I am unable to do it. A total score was calculated, with a higher score indicating greater limitations.

2.2.3. Depressive Symptoms (CESD-10)

The CESD-10, a short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, was used to measure depressive symptoms in CHARLS participants [33]. The scale consisted of 10 items, each scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (mostly or all of the time), with a total possible summary score of 0–30 points. Before the analysis, two positively phrased questions were reverse coded. Higher scores indicated higher levels of depressive symptoms. This scale has been widely used with middle- and older-aged Chinese adults and has good internal validity [34].

2.2.4. Covariates

In this study, sociodemographic factors include age (in years), gender (1 = male and 2 = female), education (0 = less than primary school, 1 = primary school, 2 = secondary school, 3 = high school or vocational school, and 4 = college/associate degree or bachelor’s degree or above), number of chronic diseases, and self-rated standard of living (1 = very high, 2 = relatively high 3 = average, 4 = relatively poor, and 5 = very poor). These are important factors that influence mental health in late adulthood. Therefore, we controlled for age, gender, education, number of chronic diseases (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer or malignant tumor, chronic lung diseases, liver disease, heart problems, stroke, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive diseases, arthritis or rheumatism, asthma, memory-related disease, and emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems), and self-rated standard of living using the 2011 data in the following cross-lagged analyses.

2.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses and correlations were performed using SPSS 27.0. Mplus 8.3 was subsequently used to conduct cross-lagged and model fit analyses. Specifically, a five-wave cross-lagged path model (CLPM) was used to examine the longitudinal relationships between IADL, SRH, and depressive symptoms. Several indices were used to evaluate the goodness of fit, including χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Model fit was deemed acceptable if the CFI was above 0.90 and the RMSEA and SRMR were less than 0.08 [35]. The indirect effects in this study were based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples. The mediating effect was considered significant if the CI did not include zero [36].

The CLPM included autoregressive paths from wave t to wave t + 1 and wave t to wave t + 2 for each of the three key variables. The model also tested prospective associations between IADL at Wave t and SRH and CESD-10 at Wave t + 1. The prospective association between SRH at Wave t and CESD-10 at Wave t + 1 was also included in the model. Furthermore, the CLPM simultaneously examined paths in the opposite direction: CESD-10 at Wave t predicted SRH and IADL at Wave t + 1, and SRH at Wave t predicted IADL at Wave t + 1.

Finally, multigroup analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the model fit for the overall sample differed as a function of age. Group comparisons were performed by testing model invariance between the unconstrained and constrained models by setting the cross-lagged paths as equal. Model invariance was tested by examining the changes in CFI; a ΔCFI of 0.01 or larger indicated significant group differences [37, 38]. The Wald test for parameter constraints was used to test the moderating effects.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents participants’ characteristics. A total of 4830 participants were included in the five survey waves. At the baseline, the mean age of participants was 55.61 years (SD = 7.20); 51.9% were male, 37.8% had not finished primary school, and they had an average of 1.27 chronic diseases. The average score for standard of living was 3.49.

| Variable | Total (N = 4830) | Middle (n = 4265) | Older (n = 565) | t/X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IADL | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.53 | −2.603 | < 0.001 |

| SRH | 2.92 | 2.92 | 2.96 | −1.031 | 0.302 |

| CESD-10 | 7.56 | 7.56 | 7.59 | −0.126 | 0.900 |

| Age | 55.61 | 53.89 | 68.66 | −86.164 | < 0.001 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 1.27 | 1.23 | 1.59 | −5.609 | < 0.001 |

| Self-rated standard of living | 3.49 | 3.50 | 3.39 | 3.534 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 40.309 | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 51.9% | 50.2% | 64.4% | ||

| Female | 48.1% | 49.8% | 35.6% | ||

| Education | 93.367 | < 0.001 | |||

| Less than primary school | 37.8% | 35.9% | 52.7% | ||

| Primary school | 23.3% | 23.0% | 25.1% | ||

| Secondary school | 25.1% | 26.7% | 12.4% | ||

| High school or vocational school | 12.0% | 12.7% | 7.3% | ||

| College/associate/bachelor degree or above | 1.8% | 1.7% | 2.5% |

Independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted to examine the age differences. Only one significant age-related difference was found for the key variables: IADL was more severe in older than in middle-aged adults (p < 0.001). Regarding demographic variables, older adults reported more chronic diseases (p < 0.001) and a lower standard of living (p < 0.001). The distribution of sex and education level among the middle-aged and older groups also differed (p < 0.001).

Supporting Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the key variables. All correlations among key study variables were in the expected directions.

3.2. Longitudinal Linkages Between IADL, SRH, and CESD-10

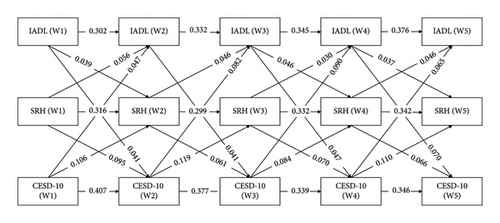

We fitted a CLPM to examine the bidirectional lagged effects of IADL, SRH, and CESD-10 scores among middle-aged and older Chinese adults, as shown in Figure 2. The model showed an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (45) = 646.928; CFI = 0.978; RMSEA = 0.053; and SRMR = 0.024) (Supporting Table 2).

As Figure 2 indicates, the paths from IADL to CESD-10 and from CESD-10 to IADL were significant. In addition, bidirectional links between CESD-10 and SRH and between SRH and CESD-10 were observed except for path “IADL (W2) ⟶ SRH(W3).”

3.3. Mediation Analyses

Both indirect paths “IADL ⟶ SRH ⟶ CESD-10” and “CESD-10 ⟶ SRH ⟶ IADL” were tested, and the results proved significant (Table 2). For example, the results showed that the path from IADL (W1) to CESD-10 (W3) via SRH (W2) was significant (β = 0.002 and 95% CI = [0.001, 0.004]) and the path from CESD-10 (W1) to IADL (W3) via SRH (W2) was also significant (β = 0.005 and 95% CI = [0.002, 0.008]). Therefore, a more severe IADL disability predicted lower SRH and more depressive symptoms and vice versa. It is also worth noting that all indirect paths “CESD-10 ⟶ SRH ⟶ IADL” were significant, while only two indirect paths of “IADL ⟶ SRH ⟶ CESD-10” were significant.

| Pathway | Indirect β | 95% CL |

|---|---|---|

| IADL ⟶ SRH ⟶ CESD-10 | ||

| W1 ⟶ W2 ⟶ W3 | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.004] |

| W2 ⟶ W3 ⟶ W4 | 0.002 | [0.000, 0.003] |

| W3 ⟶ W4 ⟶ W5 | 0.003 | [0.001, 0.005] |

| CESD-10 ⟶ SRH ⟶ IADL | ||

| W1 ⟶ W2 ⟶ W3 | 0.005 | [0.002, 0.008] |

| W2 ⟶ W3 ⟶ W4 | 0.004 | [0.001, 0.007] |

| W3 ⟶ W4 ⟶ W5 | 0.004 | [0.001, 0.007] |

3.4. Moderating Effects of Age

To examine the moderating role of age, the dataset was divided into two groups: middle-aged and older adults. Multigroup analysis was used to examine the differences between groups (Figure 3). When the cross-lagged path coefficients across groups were restricted to be equal, the constrained model did not significantly differ from the unconstrained model (ΔCFI = 0.001) (Supporting Table 3). However, the Wald test statistic revealed that significant age differences existed in four pathways: (a) the path from SRH(W4) to IADL(W5) (Wald χ2 (1) = 9.206, p = 0.002); (b) the path from CESD-10 (W3) to IADL(W4) (Wald χ2 (1) = 4.871, p = 0.027); (c) the path from CESD-10 (W2) to IADL (W3) (Wald χ2 (1) = 5.289, p = 0.022); and (d) the path from IADL (W2) to SRH (W3) (Wald χ2 (1) = 4.696, p = 0.030).

Mediation tests were conducted on each group (Table 3). For the middle-aged group, both indirect paths “IADL ⟶ SRH ⟶ CESD-10” and “CESD-10 ⟶ SRH ⟶ IADL” were supported, and both were significant. For the older group, only “CESD-10 (W3) ⟶ SRH (W4) ⟶ IADL (W5)” was significant.

| Pathway | Middle-aged group | Older group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect β | 95% CL | Indirect β | 95% CL | |

| IADL ⟶ SRH ⟶ CESD-10 | ||||

| W1 ⟶ W2 ⟶ W3 | 0.003 | [0.001, 0.005] | 0.001 | [−0.001, 0.010] |

| W2 ⟶ W3 ⟶ W4 | 0.001 | [−0.001, 0.003] | 0.008 | [0.000, 0.019] |

| W3 ⟶ W4 ⟶ W5 | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.005] | 0.008 | [0.000, 0.021] |

| CESD-10 ⟶ SRH ⟶ IADL | ||||

| W1 ⟶ W2 ⟶ W3 | 0.002 | [0.000, 0.005] | 0.003 | [−0.009, 0.017] |

| W2 ⟶ W3 ⟶ W4 | 0.004 | [0.001, 0.008] | 0.004 | [−0.006, 0.015] |

| W3 ⟶ W4 ⟶ W5 | 0.005 | [0.002, 0.009] | 0.013 | [0.001, 0.026] |

4. Discussion

This study used cross-lagged panel models to verify the bidirectional relationships among IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Our findings supported the research hypotheses. First, a bidirectional relationship was found between IADL disability and depressive symptoms, where higher levels of IADL disability were associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms and vice versa. Second, SRH longitudinally mediated the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms. Higher levels of IADL disability led to decreased SRH, which further increased the risk of depressive symptoms and vice versa. Third, age (middle-aged or older) moderated the bidirectional relationships among IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms. Compared with older adults (aged 65 years and above), the middle-aged group (ages 45–64) showed significant mediation pathways in five mediation models, suggesting that SRH may have a more significant mediating effect on the bidirectional relationship between IADL disability and depressive symptoms in middle-aged adults.

We found consistent and significant bidirectional relationships between IADL disability and depressive symptoms in the five-wave follow-up data for both middle-aged and older Chinese adults. However, the predictive strength of depressive symptoms for IADL disability was lower than that of IADL disability on depressive symptoms. One study suggested that in longitudinal relationships, depression and IADL/ADL reinforce one another over time, with the impact of IADL on depression being faster and stronger in 1-year lagged analyses [39]. This finding suggests that factors other than depression may significantly predict IADL disability. Several studies have empirically demonstrated the relationship between IADL disability and depression [13, 40]. The standard explanation for this relationship is the social role and stress-process model. From the perspective of social roles and social support, a decline in the ability to independently complete daily tasks may lead to a withdrawal from meaningful social roles and threaten life goals, which, in turn, predict an increase in depressive symptoms [41]. In addition, the inability to fulfill social roles can affect independence, self-esteem, meaningful activities, and social interactions, leading to late-life depression [39, 42]. Meanwhile, depressive symptoms reduce the motivation to maintain good nutrition and follow medical advice, leading to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness through the psychoneuroendocrine pathways [39, 43]. The stress-process model is another significant mechanism used. Research suggests that physical limitations are sources of chronic or persistent stress, with chronic stress, particularly depressive symptoms, being strong predictors [44]. Repeated and prolonged failures in IADL may lead to a loss of control and helplessness. When individuals cannot overcome chronic stressors, their resilience may decrease, making them more vulnerable to psychological distress, including depressive symptoms [41].

Our results indicate that IADL disability leads to decreased SRH, which, in turn, increases the risk of depressive symptoms. Conversely, significant depressive symptoms lead to decreased SRH, which increases the risk of IADL disability. Moreover, the longitudinal mediating effect of SRH on the depressive symptoms-SRH-IADL disability path is more stable than that on the IADL disability-SRH-depressive symptoms path. This study thus proposes that potential mechanisms underlie the bidirectional association between IADL disability and SRH. For example, Mandal et al. [45] suggested that functional limitations are associated with decreased self-care ability and fulfillment of social roles, leading to dependency and undermining autonomy, ultimately resulting in negative SRH. Tomioka, Kurumatani, and Hosoi [20] proposed that cardiovascular diseases, social engagement, and stress management could explain the predictive role of SRH in IADL disability. Older adults with better SRH have a lower incidence of cardiovascular diseases, are more likely to engage in social activities, and have sufficient capabilities to cope with stress, which help prevent a decline in IADL function. The bidirectional association between SRH and depressive symptoms may be attributed to shared risk factors. From a psychological perspective, SRH predicts the increased severity of depression, possibly because vitality, daily concerns, stress from significant life events, and low self-esteem form the basis of SRH, which is closely related to depression [25]. Symptoms of depression and anxiety, including sleep disturbance, lack of concentration, irritability, and fatigue, also lead to negative perceptions and emotions about one’s health, reducing quality of life, which may be the primary reason for poor SRH [21, 25, 46]. From a physiological perspective, depressive symptoms are associated with chronic inflammatory responses that may lead to various health issues, thereby affecting SRH [46].

Limited evidence confirms the mediating role of SRH in the longitudinal association between IADL disability and depressive symptoms, as existing studies only indicate an association between depressive symptoms and SRH [26, 47, 48] and that SRH is a reliable predictor of subsequent ADL/IADL disability in life [49, 50]. Therefore, this study is the first to simultaneously verify the bidirectional association of SRH with both IADL disability and depressive symptoms, as well as its mediating role between the two. This finding suggests that SRH could serve as a potential mechanism in related interventions and treatments. This study also shows that SRH has a more significant and stable mediating effect on the path through which depressive symptoms predict IADL disability, highlighting the importance of screening and intervention in SRH to prevent IADL disability, especially among populations with depressive symptoms.

Our findings also show the moderating role of age in this model because the mediating effect of SRH was not as significant or stable in the older adult group as in the middle-aged adult group. Current research suggests that, as age increases, the relationship between SRH and mental health may not improve or may remain stable [28]. The weakened association between SRH and physical health may be due to the adaptation to health issues and the redefinition of health [27]. Older adults are more accustomed to dealing with health-related issues or may have access to medical care and rehabilitation, which could counteract health deterioration effects [27, 28, 39]. Specifically, this redefinition may lead older adults to make more optimistic health assessments than middle-aged adults, even when objective health conditions are in decline. Moreover, they tend to compare their health status with that of their peers, with the oldest individuals (baseline age 83 years and older) having the most optimistic assessment of their health relative to their actual physical condition [27, 28]. Based on this social comparison, older adults are also better able to maintain their SRH compared with middle-aged individuals, which may reduce the impact of objective health changes, such as functional disability, on SRH and mental health. Therefore, targeted interventions should be designed for specific SRH and behaviors across different age groups to effectively improve the wellbeing of both middle-aged and older adults.

4.1. Implications

This study has several theoretical and practical implications. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to use five waves of longitudinal follow-up data to explore the bidirectional associations among IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we observed a vicious cycle between IADL disability and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Our findings illustrate the longitudinal mediating effect of SRH on this vicious cycle, providing empirical evidence on the association and underlying mechanisms between IADL disability and depressive symptoms.

From a practical perspective, focusing on the bidirectionality of IADL disability, SRH, and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults helps researchers assess health status and quality of life more accurately. It also provides directions for future research on health interventions and management. As such, healthcare providers should focus more on middle-aged and older adults with IADL disabilities and design targeted interventions that address the decline in IADL functioning and potentially benefit their mental health. Helping middle-aged and older adults improve their SRH may interrupt the potential vicious cycle linking IADL disability and depressive symptoms. Researchers should also consider age-related issues when studying the prevention of IADL disability and depressive symptoms, with particular emphasis on middle-aged adults.

4.2. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, the measures employed in this study were solely based on self-reports, which may have resulted in information bias. Second, the age distribution of CHARLS is representative of an authoritative national database in China. However, most CHARLS respondents were slightly younger than the age distribution of middle-aged and older adults in China’s general population. This might be explained by older adults’ inability to take the survey due to various circumstances, such as cognitive impairment. Therefore, to more precisely investigate the relationships among these health indicators, a significant number of covariates should be included in future studies. Furthermore, the database included only Chinese adults, limiting the generalizability of the results to other cultural contexts. This study should be replicated using different cultural samples to validate our results. Finally, caution is required when using cross-lagged models to explain causal links, as other variables may explain the association between IADL scores and depression. Further investigations are needed to examine this topic from various perspectives.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated significant bidirectional relationships between IADL disability and depressive symptoms among Chinese middle-aged and older adults. IADL disability predicted depressive symptoms more strongly than the reverse path did. SRH mediated the longitudinal relationship between the two factors. Compared with older adults, SRH had a more significant impact on the association between IADL disability and depression in middle-aged adults. When developing intervention plans for IADL disability or depression, the bidirectional nature and significant role of SRH must be considered, paying particular attention to middle-aged adults approaching old age.

Ethics Statement

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Disclosure

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Departmental Incentive Scheme offered by the Department of Social Work, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from the Zhejiang Provincial Cultural Innovation Research Center. We also appreciate the CHARLS research team, field teams, and every respondent for the CHARLS project.

Supporting Information

Supporting Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations for key variables.

Supporting Table 2 shows goodness-of-fit indices for the cross-lagged panel models of overall sample.

Supporting Table 3 shows goodness-of-fit indices for the multigroup models.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in CHARLS at https://charls.charlsdata.com/users/signin/en.html.