Exploring Effect of Psychological First Aid Education on Elementary School Teachers: A Quasiexperimental Study

Abstract

Background: Psychological first aid (PFA) is a supportive approach for children experiencing distress and in need of immediate assistance. It assists children in feeling safe, connected with others, and staying calm and hopeful. Furthermore, it also helps children gain access to social, physical, and emotional support and empowers them as individuals and part of the community. Teachers are the largest workforce in Jordan. However, they are rarely trained in PFA to handle critical events among children.

Aim: This study examined the impact of a PFA training program on elementary school teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy.

Methods: This quantitative, quasiexperimental, nonequivalent control group design utilized pre- and posttest results. A total of 80 elementary school teachers were divided into two groups, experimental (n = 40) and control (n = 40), assigned on a nonrandom basis to two elementary schools in Jordan. Teachers completed self-assessments that measured knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy related to PFA.

Results: The experimental group exhibited significantly higher mean scores across all domains compared with the control group postintervention. Furthermore, the experimental group had higher mean knowledge, skills, and attitude scores of 8.12, 7.97, and 8.05 compared with the control group, 5.83 (t = 9.17, p ≤ 0.001), 5.05 (t = 10.34, p ≤ 0.001), and 4.90 (t = 9.91, p ≤ 0.001), respectively. Additionally, self-efficacy scores were significantly higher in the experimental group, with a mean of 143.10 (±15.83) compared with the control group (85.55) (t = 2.17, p ≤ 0.001).

Conclusion: The PFA training program substantially improved teachers’ competencies in delivering psychological support during crises and enhanced knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy across all variables.

Implications: This study provides evidence that teachers’ PFA training can enhance their knowledge, skills, attitude, and self-efficacy. Teachers can be trained to support children experiencing distress and in need of immediate assistance during crises until they can be seen by professionals, such as psychiatric or social workers.

1. Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are the pivotal stages of physical and mental development. Worldwide, one in seven adolescents aged 10–19 years experiences a mental disorder, contributing to 13% of the global disease burden in this age group [1]. The prevalence of mental health issues among Jordanian children and adolescents is rapidly increasing. Evidence indicates that the prevalence rates for depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), general emotional problems, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were 74%, 47%, 40%, 55%, and 65%, respectively [2]. Furthermore, children witnessing distressing images of the Gaza war on social media have been observed to trigger stress symptoms [3]. Mental health issues often remain unrecognized and untreated [1] which can potentially lead to suicide. In fact, suicide was the fourth leading cause of death among individuals aged 15–29 years worldwide in 2019, with 77% of all suicides occurring in low- and middle-income countries [4].

Studies conducted in other countries reported that sociodemographic factors such as culture, language, socioeconomic status, deprivation, perceived threat, and loneliness affect mental health [5, 6]. However, studies by AlHamawi et al. [2] and Yonis et al. [7] reported that sociodemographic factors also affect children mental health. They reported being a female, refugee or displaced person, and experiencing a traumatic stressful life event, such as discrimination, separation from families, death of family members, violence, and pandemic isolation were the main risk factors that made children vulnerable to mental health problems.

The inability to effectively manage or cope with a stressful life event may trigger a crisis, which is a disruption of the regular events in a person’s daily life or lives of those around them [8]. Furthermore, revictimization [9], neglect, maltreatment and stigmatization [10], decline in physical activity and fitness [11], and reduced educational achievements and, consequently, impaired general adult life [12] are common negative effects of psychological distress among children and adolescents.

Studies have revealed that support from teachers can significantly improve adolescents’ mental well-being by decreasing negative emotions and increasing resilience [13–15]. In this context, psychological first aid (PFA) has emerged as an effective and accessible tool for early intervention in school settings and supports teachers in offering immediate and practical help to students affected by crisis events [16].

Sokol et al. [17] conducted a systematic review to identify school-based crisis intervention protocols, descriptions, and evaluations and identified several approaches to manage students’ psychological distress in crisis events, such as suicide, death of family members or loved ones, natural disasters, community violence, or terrorism. Furthermore, they stated that different approaches were used to manage students’ suffering, such as the formation of crisis networks, community crisis interventions, mini-marathon groups, crisis management briefings, adolescent suicide prevention programs, and PFA.

Literature reveals that PFA training impacts teachers’ knowledge and skills [2, 18, 19]. Teachers are often the first to encounter students dealing with emotional or psychological challenges; hence, it is crucial that they possess the appropriate skills and knowledge to assist such students [2]. PFA training significantly enhances teachers’ abilities to recognize signs of distress and offer effective support. AlHamawi et al. emphasized the importance of equipping teachers with the skills to manage these issues in the classroom. Teachers trained to recognize signs of mental distress can provide crucial early interventions, which can improve students’ overall well-being [2]. Similarly, Makwana [18] reviewed the mental health impacts of both natural and man-made disasters [18] and emphasized the importance of postdisaster psychological interventions, particularly in schools. The author highlighted the role of disaster management and mental health training in preparing educators to handle crises. Additionally, Kaya and Ayker emphasized the importance of disaster preparedness training for teachers. Appropriate training, whether PFA or other types of emergency management, is crucial for enhancing teachers’ ability to effectively respond during crises; disaster risks and injuries can be reduced with appropriate knowledge and preparedness [19].

Studies have also discussed the influence of PFA training on teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy [20–22]. Self-efficacy refers to one’s belief in their ability to perform specific tasks and is a key component of effective teaching. Training programs to increase self-efficacy can enhance teachers’ confidence in managing crises and providing emotional support to children in distress [20]. Sijbrandij et al. reported that training significantly increased participants’ knowledge of psychosocial responses and improved their understanding of how to support individuals in distress [21]. However, the study did find significant improvements in professional attitudes or confidence immediately posttraining. Similarly, Wang et al.’s scoping review reported that training programs significantly improved participants’ knowledge and self-efficacy in providing psychosocial support [23]. Furthermore, PFA training had a positive impact on sophomore vocational nursing students’ self-efficacy and resilience [22].

Abu Sabra et al. focused on the impact of PFA training on teachers and found that faculty members exhibited significant improvements, in terms of both knowledge and competencies, in dealing with children who had experienced traumatic events [24]. Furthermore, Nair et al. assessed the impact of PFA training on nurses and noted improvements in their self-efficacy in providing psychosocial interventions. Although the training did not significantly affect knowledge, it increased participants’ self-confidence to handle stressful situations [25]. Rahmatulloh et al. found that while teachers experienced increased self-efficacy after the training, no similar improvement in their PFA knowledge was observed [26].

Global statistics emphasize the need for an international perspective on childhood mental health and underscore the importance of increasing service access and intervention strategies globally [27–29]. According to Barican et al., the prevalence of childhood mental disorders is 12.7%, with that of anxiety disorders at 5.2%. Additionally, the authors found that 26.5% of children with mental health disorders have two or more co-occurring conditions. Only 44.2% of children affected with mental health disorders receive any services, revealing a significant global gap in care provision [27]. Hossain et al. highlighted the complexity of childhood mental health issues, which can have long-term biopsychosocial consequences, further emphasizing the need for early interventions [28].

Kaku et al. provided more specific statistics from various regions concerning the prevalence of mental health disorders. In South Africa, a provincial study found a 17% prevalence rate, with generalized anxiety disorder being the most common disorder. In Chile, 22.5% of children and adolescents have been diagnosed with mental disorders, with this prevalence being higher among females (25.8%) compared to males (19.3%). In France, 5% of children under 12 years suffer from anxiety disorders and 0.5% from depression. In Italy, the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents stands at 8% [29].

However, the literature in this context has some weaknesses, including the limited focus on elementary education. The majority of the studies focus on secondary education or health professionals, leaving a gap in research on how PFA training affects elementary school teachers. A literature review focused on Youth Mental Health First Aid reported significant improvement in mental health literacy among college students and educators. However, the research revealed a deficiency in control groups, lack of long-term follow-up studies, and considerations of cultural diversity, which limits the comprehensive support for Youth Mental Health First Aid [30].

Additionally, there is a lack of longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of PFA training on teachers’ professional development.

Elementary school teachers in Jordan constitute a substantial portion of the teaching workforce across various educational levels. In light of the diverse and stressful challenges that students encounter, ranging from devastating wars, natural disasters, and other domestic issues, there is an increasing need for psychological care training specifically aimed at elementary school teachers. Unfortunately, in case of emergencies, this large sector of elementary school teachers in Jordan seldom receives PFA training.

PFA training can significantly enhance teachers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and preparedness to respond to student crises. However, research should focus specifically on elementary school teachers and explore the long-term effects of PFA training on classroom management and student outcomes. A comprehensive training approach that combines PFA, emotional intelligence, and classroom management is essential to prepare teachers to handle their students’ diverse needs. By improving teachers’ ability to respond to student crises, PFA training can help create a supportive and effective learning environment for all students.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of a PFA training program on elementary school teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study utilized a quasiexperimental design, specifically, a nonequivalent control group pre- and posttest design. This study recruited two groups of teachers and assigned them to the study conditions on a nonrandom basis. Subsequently, the researchers measured their knowledge, skills, attitude, and self-efficacy.

2.2. Sample and Sampling

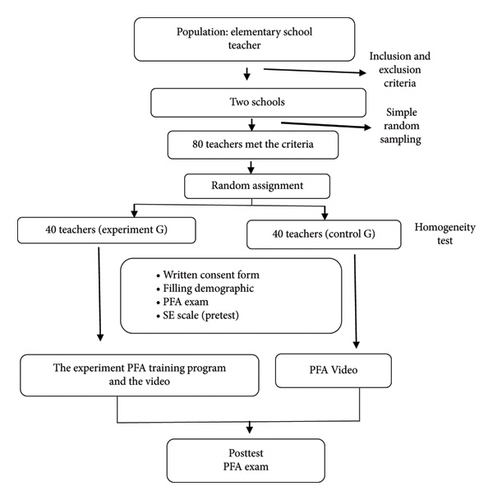

The researchers used a simple random sample to select two schools from a group of elementary schools affiliated with the Ministry of Education. Subsequently, they were randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group at the school level. This study selected 40 teachers from each school (Figure 1). Notably, in Jordan, female teachers are assigned to teach children until after the fourth grade. Therefore, only female teachers were included.

The inclusion criteria were teachers who were active in elementary school during the academic year 2023/2024 and had no prior formal training in PFA. A total of 80 teachers, 40 in each group, met the eligible criteria. The number of participants was calculated based on Raosoft’s criteria [31], with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. The required sample size was 80 participants (Figure 1).

2.3. Intervention

The researchers modified and adapted the PFA: Guide for Field Workers by the World Health Organization to ensure that it was culturally and linguistically appropriate for the teachers [32]. Modifications included adjustment of the formal Arabic language to the Jordanian dialect and accent and incorporation of culturally relevant examples, values, and practices to enhance engagement and comprehension. These changes were reviewed by two community experts in linguistics and qualified Arab psychologists to ensure cultural sensitivity and appropriateness. Preliminary feedback from teachers during the pilot study indicated that the Arabic version of the questionnaire items is clearly stated, comprehensive, and relevant to the program content.

Table 1 presents the flow of the research procedure, and Table 2 presents the contents of the PFA program “Teachers: You Can.” They administered the “Teachers: You Can” program in a structured way and incorporated various active and cooperative teaching methods based on the type of program content (knowledge, skill, or attitude) [22, 24]. These methods included verbal instruction, role-play, visual aids, hands-on activities, simulations, real-life demonstrations, case studies, and group work to meet varying preferences. Researchers encouraged teachers to share their experiences, concerns, suggestions, and true stories regarding their students’ crisis events and created a space for dialogue that respected teachers with heart-breaking stories. Researchers used familiar and well-known local crises that affected children to motivate teachers to suggest their PFA intervention.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Preintervention assessment | Both groups completed a pretest to assess knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy related to PFA. This provided baseline data |

| Step 2: Educational video introduction | Both groups watched an 8-min video entitled “PFA in Disaster Situations” |

| Step 3: PFA knowledge, skills, development, and attitude | Experimental group underwent the “Teachers: You Can” program |

| Step 4: Postintervention assessment | Both groups completed a posttest to measure changes in PFA knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy, which allowed for a comparison between the two and evaluation of the program’s effectiveness |

| Number of section | Duration | Session topic | Frequency | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1 h | Introduction | Weekly | Introduce the concept, importance, and core principles of PFA. Define roles and responsibilities |

| Second | 1.5 h | PFA Core Actions | Review the three core actions: Look, Listen, and Link. Explain each step with examples and scenarios | |

| Third | 2 h | Active Listening Skills | Teach active listening and nonverbal communication skills. Practice with role-play activities | |

| Fourth | 1.5 h | Discovering Emotional Distress | Learn signs of distress in students. Conduct group discussions and scenario analysis | |

| Fifth | 2 h | Providing Relaxation and Stability | Practice offering emotional comfort and practical assistance. Engage in case studies and exercises | |

| Sixth | 1.5 h | Combining Community Resources | Identify local mental health resources. Create strategies for referrals and ongoing support | |

| Seventh | 1 h | Crisis Cultural Sensitivity | Emphasize the importance of cultural competence. Discuss cultural adaptation in PFA delivery | |

| Eighth | 1 h | Self-Care for PFA Providers | Review stress management techniques and coping strategies for PFA providers | |

| Ninth | 2 h | Review and Skills Assessment | Conduct a comprehensive review and assessment through simulations. Provide feedback and guidance |

Table 2 summarizes the intervention training program and details the goals, focus, and length of each session. Each of the program’s nine weekly sessions aimed to increase the instructors’ abilities to provide crisis-related psychological support. The sessions covered basic PFA principles, useful abilities, such as emotional support and active listening, and crucial self-care techniques. This methodology enabled replication and thorough assessment of the program’s efficacy in improving teachers’ crisis response skills. The researchers administered the “Teachers: You Can” program to the experimental group in a fostering and positive learning environment. Furthermore, they provided motivated positive feedback and small praises. Subsequently, they played an 8-min PFA in Disaster Situations video (Arabic version). The video was designated by the Dr. SMART TEAM, 2024, and is freely available to the public on YouTube.

The theoretical content of “Teachers: You Can” program included the definition of PFA, its purpose and importance in crisis situations, major concepts, and core actions such as “Look, Listen, Link,” in addition to ethical considerations when offering PFA. PFA skills included active listening, nonverbal communication, assessment of emotional and psychological needs, provision of emotional comfort, calmness, emotional and practical support, and connection to individuals with appropriate community resources. PFA attitudes addressed teachers’ attitudes toward PFA, fostered empathy, patience, and cultural sensitivity via a nonjudgmental and compassionate approach to support individuals in crisis, maintaining dignity and respect for the individuals who were affected, and openness and caring. The “Teachers: You Can” program ensured that teachers were technically competent and also emotionally prepared to provide PFA in a manner that fostered trust and emotional safety. The control and experimental groups simultaneously watched “the Dr. SMART Team-PFA in Disaster Situations” video. This 8-min video provided an overview of how to support people experiencing distress due to crises, trauma, or disasters. It covered the same content, skills, and attitude of the “Teachers: You Can” program. It was culturally and linguistically appropriate for lay people. Table 1 presents the research procedure for both research groups.

2.4. Instruments

This study used an online self-reported questionnaire to collect the following data.

2.4.1. Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables included gender, age, monthly income, educational level, marital status, and parenthood history.

2.4.2. Psychological First Aid Knowledge, Skills, and Attitude (PFAKSA) Questionnaire

The authors developed the PFAKSA questionnaire. It was designed to assess teachers’ level of understanding knowledge, practical ability (skills), and mental disposition (attitude) related to a specific role and provided a comprehensive evaluation of participants’ competencies in PFA. Researchers relied on relevant resources, such as the Arabic Version of PFA Guide for Field Workers [32] and PFA Facilitator’s Manual for Orienting Fieldworkers [33], to construct 30 multiple-choice questions that assessed PFA knowledge, skills, and attitude. The PFA manual [33] was designed to train helpers who offer PFA to individuals who were distressed following a crisis event with compassionate, supportive, and practical assistance while considering the individuals’ dignity, culture, and capabilities.

To ensure their accuracy and validity, the questions were independently reviewed and validated by three experts: a psychologist, a psychiatric nurse at the doctoral level, and a qualified clinical psychologist.

Knowledge questions (10 items) evaluated an individual’s understanding of key concepts related to PFA, such as its definition, importance, provider, and timing. Skills items (10 items) assessed individuals perceived practical abilities in administering PFA, which included communication, calming individuals who were distressed, handling situations where help was refused, and providing practical support. PFA attitudes (10 items) measured individuals’ perspectives toward PFA, such as sense of responsibility, the importance of creating a safe environment, and the role of culture in providing PFA.

Each item was scored as 1 or 0 points for correct and incorrect responses, respectively. The total possible score ranges from 0 to 30 points.

2.4.3. PFA Application of Self-Efficacy Scale

The PFA application of self-efficacy scale was used to assess teachers’ precrisis competencies in providing PFA and quality of their responses. Researchers used Kılıç Bayageldi and Şimşek’s tool to measure overall self-efficacy [34]. It comprised 35 items rated on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 = not at all appropriate, 2 = not appropriate, 3 = moderately appropriate, 4 = appropriate, to 5 = completely appropriate. The total score was 175 points. According to Kılıç Bayageldi and Şimşek, the construct validity was proven for the self-efficacy scale, and test–retest reliability and reliability coefficient were high (α = ≥ 0.93).

Researchers followed Brislin’s model to translate the PFA self-efficacy scale to ensure its cross-cultural adaptation trait and validity in the Arabic language [35]. To translate the self-efficacy scale, researchers used Brislin’s forward and back translation and validation methods. A bilingual expert in clinical psychology translated the tool from English into Arabic. Subsequently, another bilingual expert, unfamiliar with the original tool, translated the Arabic version back into the original language. Any discrepancies and mismatches were reconciled to improve accuracy. Subsequently, the tool underwent pilot testing with Arabic-speaking teachers (N = 10) to ensure clarity and relevance. In this study, the pre- and posttest Cronbach’s alphas of the Arabic version were 0.80 and 0.82, respectively.

2.5. Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted to assess the PFAKSA questionnaire and examine its validity. The participants were 10 Arabic-speaking elementary school teachers with similar sociodemographic characteristics to the study sample. Based on participants’ suggestions, minor modifications were made to improve clarity and relevance, which confirmed the appropriateness of the questions for the current sample. Subsequently, another pilot study was conducted with 12 teachers to determine the clarity and understand the response time. The final draft included 30 questions.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Al-Zaytoonah University’s Research Ethics Committee (No. 522/03) and the Ministry of Education (No. 9194/7/1). The right to self-determination, full disclosure, fair treatment before, during, and after intervention, and participation is voluntary, and participants can drop out without penalty. To minimize the risk of harm to the mental health status of the participants, the research, purpose methods, risks, and benefits were fully explained. In addition, privacy and confidentiality were maintained. Written consent was obtained. The principle of posttrial access was strictly maintained. Once the study results indicated that the intervention was beneficial, participants in the control group were provided with the same intervention.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

SPSS Version 25.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics, which included means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages, were employed to describe participants’ demographic characteristics in both groups. The descriptive statistics were used to summarize the participants’ demographic characteristics, providing a clear overview of the data distribution. Homogeneity test was conducted before the intervention, which confirmed that the groups were comparable regarding their baseline characteristics. A homogeneity test was conducted to ensure that the variance of the main variables was similar across groups, as variance homogeneity is a crucial assumption for comparing means using t-tests [36]. Testing for homogeneity helps confirm the validity of statistical inferences by ensuring that the differences observed between groups are not due to unequal variances, which could lead to incorrect conclusions. If variance homogeneity were violated, alternative statistical methods or data transformations would be necessary to maintain the accuracy of the analysis [36]. The effectiveness of the PFA training program was evaluated via a comparison of the pre- and posttest scores on the key outcome variables. Paired sample t-test was used to analyze the changes in knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy scores of the teachers. The paired samples t-test was the most appropriate, as it allows for the comparison of two means from the same group of participants after a particular time of being subjected to an intervention, in this case, PFA training [36]. The alpha level was set at ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

Table 3 presents the participants’ demographic data (n = 80). No significant differences were observed between the two groups based on their characteristics according to the homogeneity test (p > 0.05).

| Variable | Experimental (n = 40%) | Control (n = 40%) | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, ±) | 42.5 (±6.4) | 42.0 (±5.4) | 0.6 | |

| Number of children (M, ±) | 2.4 (±2.0) | 2.60 (±1.4) | 0.5 | |

| Number of students/classes (M ±) | 20.2 (±5.0) | 19.8 (±3.4) | 0.1 | |

| Working experience (M, ±) | 12.2 ± 6.8) | 10.4 (±4.4) | 0.4 | |

| Variables | f (%) | f (%) | Sig | |

| Education | Bachelor’s | 32 (80.0%) | 31 (77.5%) | 0.4 |

| Master’s | 3 (07.5%) | 2 (05.0%) | ||

| Diploma | 5 (12.5%) | 7 (17.5%) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 28 (70.0%) | 30 (75.0%) | 0.3 |

| Single | 7 (17.5%) | 5 (12.5%) | ||

| Widower | 3 (07.5%) | 4 (10.0%) | ||

| Divorced | 2 (05.0%) | 1 (02.5%) | ||

| Class level | 1st grade | 14 (35.0%) | 13 (32.5%) | 0.2 |

| 2nd grade | 12 (30.0%) | 12 (30.0%) | ||

| 3rd grade | 7 (17.5%) | 8 (20.0%) | ||

| 4th grade | 7 (17.5%) | 7 (17.5%) | ||

3.2. Psychological First Aid Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes

Table 4 presents a comparison of the PFAKSA scores between the experimental and control groups across pre- and posttests. No statistically significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups in the pretest regarding knowledge (p = 0.27), skills (p = 0.58), and attitude (p = 0.24). The pretest total scores were 13.47 (± 3.88) and 13.53 (± 3.50) for the experimental and control groups, respectively.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean difference | t | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment group (m, ±) | Control group (m, ±) | ||||||

| Pretest exam | Knowledge | 4.78 (1.4) | 5.10 (1.24) | −0.32 | 1.10 | 78 | 0.27 |

| Skills | 4.33 (1.4) | 4.50 (1.40) | −0.17 | 0.56 | 0.58 | ||

| Attitude | 4.38 (1.8) | 3.92 (1.58) | 0.45 | 1.16 | 0.24 | ||

| Total score | 13.47 (3.8) | 13.53 (3.50) | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.95 | ||

| Posttest exam | Knowledge | 8.12 (1.1) | 5.83 (1.11) | 2.30 | 9.17 | ≤ 0.001∗ | |

| Skills | 7.97 (1.3) | 5.05 (1.15) | 2.92 | 10.34 | ≤ 0.001∗ | ||

| Attitude | 8.05 (1.4) | 4.90 (1.43) | 3.15 | 9.91 | ≤ 0.001∗ | ||

| Total score | 24.15 (3.1) | 15.78 (3.02) | 8.37 | 12.08 | ≤ 0.001∗ | ||

- ∗Significant p value < 0.05.

Statistically significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups posttest regarding the three variables: PFA knowledge, skills, and attitude (p ≤ 0.001). The experimental group had significantly higher PFA total scores posttest (24.15, ± 3.18) than the control group (13.53 ± 3.50).

3.3. PFA Application Related Self-Efficacy

Table 5 presents the comparison of the self-efficacy mean scores regarding PFA among the groups across pre- and posttests. No statistically significant differences were observed in self-efficacy between the groups at pretest (p = 0.84). However, a statistically significant difference was observed between the groups regarding self-efficacy posttest (p ≤ 0.001).

| Between groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Intervention group | Control group | t | df | p value between groups | |

| Mean (±) | Mean (±) | |||||

| Self-efficacy score | Pretest | 83.60 (19.97) | 84.25 (21.4) | 0.02 | 78 | 0.84 |

| Posttest | 143.10 (15.83) | 85.55 (21.1) | 2.17 | ≤ 0.001∗ | ||

| Within group | ||||||

| p value | t | df | ||||

| Intervention group | ≤ 0.001∗ | 2.88 | 39 | |||

| Control group | 0.410 | 0.39 | 39 | |||

- ∗Significant p value < 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of PFA training on teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy. The findings demonstrate that PFA training significantly improved outcomes, which aligned with those of previous studies. Furthermore, the findings contributed to evidence on the importance of mental health training for educators.

This study aligned with previous research on the impact of PFA on teachers’ knowledge and skills. Sijbrandij et al. found that PFA training significantly improved teachers’ knowledge and skills in providing psychosocial support [21]. Similarly, our findings demonstrated that PFA training enhanced teachers’ ability to identify and address psychological distress in children. Specifically, the experimental group exhibited a significant increase in PFA knowledge, skills, and attitudes from pre- to posttest (p ≤ 0.001), which confirmed that PFA training equipped teachers with the necessary tools to manage student trauma. These results were consistent with those of Wang et al., who reported that PFA training improved teachers’ self-efficacy and their ability to support students in distress [23]. Additionally, AlHamawi et al. emphasized the importance of early intervention in schools in addressing mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD. In support of these findings, teachers trained in PFA were better equipped to recognize and respond to these issues and provide timely support to mitigate the long-term psychological effects [2].

This study also supported Makwana [18], Kaya and Ayker [19], and Rezayat et al. [37] findings. Similar to Makwana’s study, which stressed the need for postdisaster psychological interventions, this study revealed that PFA training significantly enhanced teachers’ abilities to handle students’ trauma and improved their self-efficacy in addressing psychological crises. Moreover, consistent with Kaya and Ayker, who highlighted the importance of disaster management and first aid knowledge, these findings suggested that PFA training was a critical component of teachers’ preparedness to manage emotional and physical crises in the classroom. Similarly, consistent with Rezayat et al. results, which emphasized the importance of training teachers in recognizing PTSD symptoms, this study supported the idea that PFA training equipped educators with the tools to identify trauma-related symptoms and provide effective, timely support, which could ultimately mitigate their psychological impact [37].

This study also found that PFA training significantly enhanced teachers’ self-efficacy, as shown by the statistically significant improvement in self-efficacy scores from pretest to posttest for the experimental group. This aligned with Nair et al. findings which found significant improvements in nurses’ self-efficacy after PFA training. Although the pretest scores exhibited no significant difference between the experimental and control groups (p = 0.84), posttest results demonstrated enhanced self-efficacy in the experimental group, which supported the effectiveness of PFA training in increasing teachers’ confidence in managing emotional crises [25].

These findings were also similar to Sijbrandij et al. [21], Wang et al. [23], and Abu Sabra et al. [24] findings. Sijbrandij et al. demonstrated that PFA training significantly increased participants’ knowledge and psychosocial support skills, which boosted their self-efficacy [21]. Similarly, Wang et al. reported that PFA training improved teachers’ self-efficacy and resilience, which enabled them to better manage students’ emotional needs, particularly during crises [23]. Moreover, Abu Sabra et al. revealed that PFA training significantly enhanced teachers’ self-efficacy in providing support to students during traumatic events and reinforced the value of such training in empowering educators [24]. Sánchez et al. literature review emphasized the significance of training school mental health professionals enable them to recognize students’ mental health need and offering offer youth mental health support [30].

These findings collectively highlight that PFA training improves self-efficacy and equips teachers with tools to support students effectively, which enhances their preparedness to handle psychological distress in the classroom.

4.1. Implications

This study demonstrates that PFA training significantly enhances teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy, making it a valuable tool in mental health training for educators. These findings suggest that PFA training should be incorporated into professional development programs to prepare teachers to identify and address psychological distress among their students. Such training is particularly important because of the rise in mental health issues among children and adolescents [2]. Teachers with improved self-efficacy are more likely to act promptly and effectively, which can reduce the risk of long-term psychological consequences for students.

Another important implication is the scalability of the PFA training. As mental health concerns increase among students globally, a need for systematic implementation of PFA training across schools is required. Educational institutions should consider making PFA training a standard component of teacher professional development for schools. This could involve partnerships between mental health organizations and educational authorities to scale training efforts and ensure consistent delivery in various school systems, especially in regions facing high psychological distress due to conflicts, natural disasters, or socioeconomic challenges. Longitudinal follow-up should evaluate the long-term impact of PFA training.

4.2. Strength and Limitations

The strengths of the references cited in this research were in the practical relevance of the studies, which demonstrate the positive effects of PFA training on teachers’ self-efficacy. The studies consistently show that PFA training improves teachers’ ability to manage emotional and psychological crises in students.

However, the study has some limitations such as its quasiexperimental design and lack of randomization, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should use randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for stronger evidence. Additionally, self-reported data may be biased owing to social desirability or participant expectations. Future studies should use objective measures, such as observational data or student feedback, to strengthen their findings. Finally, this study did not assess the long-term retention of skills, a critical factor for sustaining improvements.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that PFA training effectively enhanced teachers’ competencies in supporting students’ mental health needs and significantly improved their knowledge, skills, attitudes, and self-efficacy. These findings aligned with the existing literature and underscored the importance of integrating mental health training into teachers’ professional development. By equipping teachers with tools to address emotional and psychological distress, PFA training can contribute to creating a supportive and resilient school environment. Despite its promising results, further research should use more robust experimental designs, longitudinal assessments, and objective measures to evaluate its sustainability and long-term impact in schools. Overall, PFA training for teachers can play a crucial role in providing timely and effective support to school children and help reduce the adverse effects of crises on their mental health and well-being.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan and the Ministry of Education, Jordan. No specific grants were received.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all teachers who participated in this research.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.