Distribution and Accessibility of Residential Aged Care Facilities Concerning Socioeconomic Indicators and Geographic Remoteness in Australia

Abstract

Objective: This study examined the distribution of residential aged care facilities in relation to the aged population and socioeconomic profile at the smallest geographical unit in Australia’s metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns.

Methods: An observational study was designed using the most recent open-source data from the Australian government. The aged population data and RACF locations were aggregated by SA1, remoteness, and socioeconomic profile, which were defined using the modified Monash model (MMM) and the index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage (IRSD). Remoteness was categorized into metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns, while socioeconomic factors were analyzed based on IRSD 10 deciles. The study utilized a Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) to perform the analysis and mapping of RACF distribution and accessibility. All collected data files were overlaid and linked using the join function in QGIS for comprehensive analysis at the Statistical area level 1 (SA1). Centroids were calculated for each SA1 to represent the geographical center of the area. The buffer function was performed to determine the proportion of the aged population residing within the specified distance thresholds of 2.5 km, 5 km, and over a 5 km radius from these facilities.

Results: Geographic disparities: The findings indicate shortages of RACF places’ availability, with only 5% of the older population living in metropolitan and large rural towns having access to such places. The number drops to 4% for those living in regional centers. The majority of older metropolitan residents reside within a 5 km radius of RACFs, compared to large rural areas (14%) and regional centers (23%), where the elders reside over the study distance threshold. The shortage of available places and the travel distances to these services may lead older adults who cannot live independently to seek alternative aged care services or remain at home. This might result in inadequate health services tailored to their specific needs which may contribute to poor health outcomes, increased in emergency room presentations, and unplanned hospital admissions.

Socioeconomic Disparities: The distribution of RACFs varied significantly across different socioeconomic profiles in favor of people with a lower socioeconomic background across the study, measured using the IRSD. Area.

Conclusion: Urgent policy interventions are needed to expand RACFs’ capacity and to establish new facilities in areas with the greatest need. The aged health system needs increased funding, improved workforce conditions, and equitable resource allocation to create a sustainable aged care system with a high-end quality of care.

1. Introduction

Globally, the aging population has been a major concern since the 1990s [1]. In 2020, Australians aged 65 years and more totaled 4.2 million, which is 16% of the total Australian population [2]. This figure is projected to be between 6.4 million and 6.7 million people in 2042 [3].

As people age, they become more prone to frailty due to declining health and worsening chronic health conditions, leading to falls and disability. Frailty, a condition characterized by reduced strength, endurance, and physiological function, affects the ability of older adults to live independently and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes [4]. In 2016, over half of 3.7 million Australians aged 65 or older were either frail (415,769) or prefrail (1,577,362), marking a 20.5% increase compared to 2011 [5].

Furthermore, health conditions such as dementia add complexity to their overall health. In 2022, dementia was responsible for 10% of all deaths and led to approximately 25,700 hospital admissions [6]. Patients with pre-existing chronic conditions such as dementia tended to have five times longer hospital stays compared to all hospitalizations in 2023. Around 63% of dementia-related hospitalizations were of patients aged 75–89, with an increase in the age group of 80–85. In 2023, there were 84 people with dementia per 1000 Australians aged 65 and over and projected to double by 2058 [6].

The demographic shift towards an aging society, and the prevalence of chronic conditions and frailty, has increased the demand for aged health services. In Australia, the aged health services range from support for independent living at home to full-time care in a residential setting [7]. In June 2023, there were 456,000 aged care service beneficiaries in Australia, with 42% of the utilization toward residential aged care facilities (RACFs). From 2021 to 2023 alone, the number of people receiving permanent residential aged care increased by 7156, reaching a total of 250,273 beneficiaries with an average stay of 36.7 months, and the average age of residents is in the mid 80s [8, 9]. This specific group (aged 85 and older) totaled 528,000 and is estimated to reach 2.2 million by 2066 [2]. These trends underpin the urgency for well-distributed aged health services to support the growing number of elders requiring specialized care. The RACFs in Australia are responsible for individuals with higher frailty scores [10].

Equitable and accessible aged care is essential to support the rapid growth of the aging population, particularly in a large country such as Australia, where spatial accessibility and availability of health services can significantly vary. Accessibility to healthcare services has been investigated as an integral aspect of access, alongside availability, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability [11].

Previous studies have demonstrated the impact of proximity to healthcare services on health outcomes. Nearness to health services plays a significant role in the high utilization of healthcare services and declines with increased distance [12–14]. Therefore, people residing within the reach of healthcare facilities are more likely to utilize these services and achieve better health outcomes. Over the years, studies have emphasized the role of geographical approaches and the analysis of spatial distances in healthcare services [15–18]. The use of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology has grown exponentially and become essential for healthcare planning and resource allocation [18]. The application of these technologies provides clear insights into gaps and accessibility challenges in health services and identifies factors associated with service variation.

Existing studies in Australia have extensively focussed on the use and quality of RACF provision as well as certain characteristics of disease and frailty prevalence [4, 5, 11, 15]. However, a critical gap exists in the current literature on the aspect of spatial accessibility and availability challenges of these facilities. Given the growing number of older people, high rates of frailty, and chronic illness, it is imperative to assess the distribution of RAC facilities to ensure equitable access for older people and their families to these services. This urges the need for further investigation into potential disparities across Australia.

Therefore, this study utilized GIS technology to analyze these facilities’ distribution and to evaluate RACFs’ capacity in relation to the proportion of the aged population and socioeconomic profile at a high geographic resolution in Australia’s metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This research is an observational study that examines the distribution and accessibility of RACFs in relation to the aged population (aged 65 and older) and socioeconomic factors across Australia’s metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns. By employing GIS technology and data aggregation at a high geographic resolution, the study provides an overview of the current RACF accessibility.

2.2. Data Sources and Extraction

The study employed several of the most recent Australian government open-source databases, which were publicly available.

2.2.1. Population Data

Deidentified population data were obtained from the latest 2021 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census of those aged 65 and older (https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/datapacks?release=2021&product=PEP&geography=ALL&header=S) [19]. The Census provides the single most accurate snapshot of Australia and is the foundation for population estimates of each state, territory, and local government area. The ABS also takes multiple steps to ensure the reliability of census data.

2.2.2. RACF Data

Recent data for all RACF locations, including longitude and latitude coordinates, were obtained from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) GEN database. The GEN database is the most comprehensive and reliable source of data concerning aged care services in Australia. It reports on capacity and activity in the aged care system focusing on the people, their care assessments, and the services they use [18]. The included assessment of RACF places’ availability was based on the facility’s capacity rather than its vacancy or occupancy of places due to data availability.

2.2.3. Remoteness Classification

The modified Monash model (MMM) was utilized to measure remoteness. The MMM describes rurality using seven categories on a scale of MM1 for major cities to MM7 for very remote areas. The MMM was selected, over the available remoteness indexes, as it is particularly relevant for healthcare planning and resource allocation. It reflects on access to services and workforce distribution in different communities [19].

In this study, the aged population and RACF data were aggregated based on remoteness to describe geographical access in three areas: metropolitan (MM1), regional centers (MM2), and large rural towns (MM3). This study mainly focuses on these three areas, as 83% of all Australians aged 65 and older reside in these three areas. MMM is based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard–Remoteness Area (ASGS–RA) framework. MM1 areas are categorized as ASGS–RA1; MM2 areas are “categorized as ASGS–RA2 and ASGS–RA3, that are in, or within 20 km road distance, of a town with a population greater than 50,000;” and MM3 areas are “categorized as ASGS–RA2 and ASGS–RA3, that are not in MM 2 and are in, or within 15 km road distance, of a town with a population between 15,000 and 50,000” [19]. As the majority of older people, frail and prefrail populations, are concentrated in major cities and decline with the increase of remoteness, this study will examine RACF distribution in cities and urban areas (classified as MM1, MM2, and MM3).

2.2.4. The Socioeconomic Index for Areas (SEIFA)

SEIFA is used by ABS based on census data and consists of four index groups, each of which complies with data from specific subsets of variables that are selected to represent a certain dimension of the socioeconomic profile. The Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD) is one of the four groups and classifies areas according to the socioeconomic characteristics into 10 categories (deciles), from 1 (the poorest) to 10 (the wealthiest), that reflects the overall socioeconomic conditions where individuals reside [20]. The IRSD is specifically designed to capture socioeconomic disadvantage by incorporating a range of variables related to low income (between $1 and $25,999 per year), lower education (Year 11 or lower), levels of unemployment (unemployed or laborers), housing (rent less than $250 per week), and other indicators of socioeconomic conditions. These dimensions are well-suited for our study’s objectives [20].

Socioeconomic disadvantage is a well-established determinant of health, influencing access to healthcare services, health behaviors, and overall well-being [21–23]. The concept of the social gradient in health indicates that individuals residing in more disadvantaged areas often experience poorer health outcomes and reduced access to healthcare services [21–23]. Therefore, the IRSD was included in this study to assess the relationship between socioeconomic status and access to RACFs. Understanding these disparities is imperative to inform decision-makers and ensure equitable allocation of resources towards disadvantaged areas.

2.3. Geographic and Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. GIS Analytical Techniques

Quantum GIS (QGIS) software was utilized to perform spatial analysis and mapping of RACF distribution and accessibility.

2.3.2. Data Integration

All collected data files (population data, RACF locations, remoteness classifications, and socioeconomic indicators) were overlaid and linked using the join function in QGIS, allowing for comprehensive analysis at the Statistical area level 1 (SA1).

2.3.3. Centroid Calculation

Centroids were calculated for each SA1 to represent the geographical center of the area. These centroids serve as reference points for distance measurements to RACFs.

2.3.4. Buffer Analysis

The buffer function was performed to create zones around each RACF at specified distance thresholds of 2.5 km, 5 km, and over 5 km. This analysis determined the proportion of the aged population residing within these distances of RACFs.

2.3.5. Justification for Distance Thresholds

The specified distance threshold is considered reasonable for older people residing in RACFs to maintain a connection with their families and communities. Several studies emphasized the importance of family involvement in the well-being of residents and RACF proximity to family and community for RACF residents [20–22]. For example, a qualitative study conducted in Australia highlighted the role of family involvement in the well-being of RACF residents [21], particularly, through the emotional support provided by spouses and children, assistance in decision-making, and advocacy for quality care. Proximity to family promotes regular visits and creates strong connections with their loved ones in RACF. The concept of distance goes beyond mere travel metrics; many residents may lack personal transportation and rely on walking or public transit, making access even more critical. In Australia, a reasonable access threshold is defined as 60 min [23], which translates to approximately 2.5 km when walking at a standard speed of 3 km/h. For older people with limited mobility, shorter distances may be more relevant, as they rely on nearby services within walking distance or a short drive. The 5 km distance threshold was used as cities and urban areas have well-developed efficient public transportation, which can ease access to RACFs located further away. However, public transportation routes and scheduling may result in longer travel times. These two chosen distance thresholds may better capture variation in access to these facilities.

2.3.6. Microsoft Excel Software

Further analysis was performed using Excel to calculate percentages and ratios.

2.4. Ethics

As the data were collected from Australian government open-source databases, which are publicly available, an ethics exemption was obtained from the University of Western Australia (WA) Human Research Ethics Committee (2024/ET00182).

2.5. Limitation

Population data were aggregated at the SA1, the smallest geographical unit available. SA1s are geographical units built from mesh blocks used by the ABS to collect and disseminate various statistical data. This high-resolution data allow for detailed analysis of the older population distribution.

Data aggregation provides an overview of resources at the area level and can simplify data complexity. However, it has limitations; it could lead to misleading conclusions when applying the result to the individual level. This kind of data also can become outdated due to the rapid increase in the aged population, migration patterns, and changes in socioeconomic profiles.

The fact that centroids of each SA1 were used to represent the distance to RACF locations may introduce bias as the target population may reside closer or further away from SA1s’ centroids. Centroids also do not account for real-time travel factors. This is due to the fact that they ignore factors such as road networks, public transportation availability, and natural landscapes. This oversight may skew results in areas with diverse characteristics.

3. Result

3.1. Geographic Accessibility

Across the study areas, 63% of those aged ≥ 65 reside in metropolitan areas. The total number of Australians aged 65 and older was estimated at 3.6 million distributed across the 52349 SA1s: metropolitan (2.8 million), regional centers (413,209), and large rural towns (353,547).

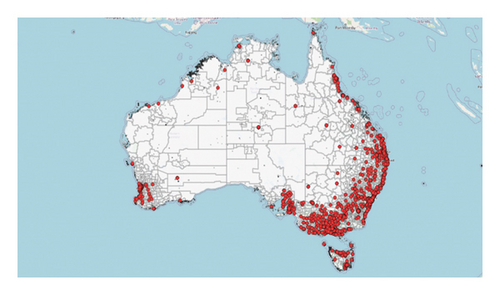

Figure 1 shows the distribution of all RACFs across Australia. In total, 194,589 RACF places were distributed across the study areas; 80% of RACF places were located in metropolitan areas, compared to regional centers and large rural towns, 10% each. New South Wales (NSW) had the highest number of RACF places (32%), followed by Victoria (VIC) (26%); the lowest number of places was recorded for the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) (1.4%), followed by Tasmanian (TAS) (2.3%).

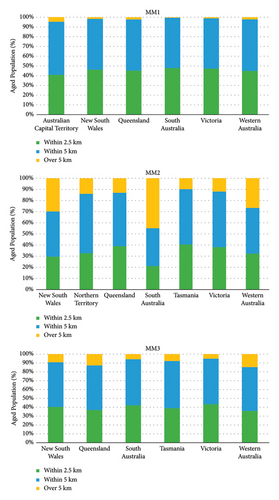

As shown in Figure 2, the distribution of RACFs across metropolitan areas in relation to remoteness and states and territories is relatively even, while regional centers and large rural towns have significant gaps in accessibility. In metropolitan areas, 97% of the older population, 77% in regional centers and 88% in large rural towns, reside within a 5 km radius of a RACF. Residing within a 2.5 km radius of a RACF, 86% of the target population is in metropolitan areas, 60% in regional centers, and 68% in large rural towns. Overall, compared across states and territories, VIC and South Australia (SA) had the most accessible RACFs in metropolitan areas (for older populations within a2.5 and 5 km radius). TAS was the most accessible in regional centers, with 70% and 84% of the target population residing within a 2.5 and 5 km radius of RACF, respectively. VIC’s large rural towns had the highest accessibility, at 77.3%, and 91% of the older population reside within 2.5 and 5 km.

The largest concentration of the older population residing over a 5 km radius of a RACF was observed in Regional centers of SA (57%), NSW (43%), WA (39%), and in large rural towns of WA (23%).

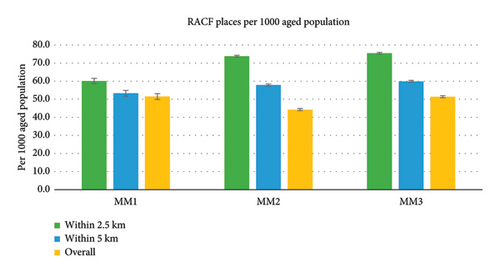

Combined across all the target study areas, 51 (95% CI: 48.9, 52.5) per capita RACF places were available as shown in Figure 3. In the metropolitan areas, the number of RACF places available was 52 per capita for the entire area. An even distribution of RACF places within the metropolitan area, with QLD, SA, and VIC metropolitan areas having the highest availability of RACF places with a ratio of 54 places per capita. ACT had the lowest ratio of 41 RACF places per capita. QLD was the most accessible within 2.5 km, with a ratio of 64 places per capita (95% CI: 62.6, 66.2).

In regional centers, there were 44 (95% CI: 43.7, 44.9) per capita RACF places available. In Tasmania (TS) and VIC, regional centers were the most accessible, with 51 per 1000 older population and the lowest found in Northern Territory (NT) at 25 per 1000. Within the defined distance threshold, SA had the highest places ratio of 182 (95% CI: 180.9, 182.9) and 112 (95% CI: 110.6, 113.1) per capita within 2.5 and 5 km, respectively. The finding should be treated with caution as 57% of the older population reside beyond 5 km from RACFs. ACT had the lowest ratio of 41 RACF places per capita. QLD was the most accessible within 2.5 km and 5 km, with 68 (95% CI: 66.3, 69.9) and 58 (95% CI: 56.6, 60.4) RACF places per capita, respectively.

In large rural towns, 51 (95% CI: 50.8, 52.0) were the available per capita RACF places. Victoria’s large rural towns were the most accessible of RACF places, with a ratio of 59 per capita. Within the defined distance threshold, all large rural towns had a relatively uniform distribution within 2.5 and 5 km radii.

3.1.1. Socioeconomic Distribution

In the studied areas, RACF places were mainly concentrated within the poorest communities as shown in Table 1. In metropolitan areas, the poorest communities had the highest distribution and access to RACF places compared to the wealthiest communities (excluding ACT, which had a higher RACF places ratio in IRSD 3–5). The ratio ranged from 71 (IRSD1) to 21 (IRSD10) per capita. In regional center areas, IRSD1 had the highest ratio of RACF places of 80 per capita. The wealthiest communities (IRSD 7–10) had the lowest RACF places ratio with an average of 19 per capita. In large rural towns, IRSD1 had the highest ratio of RACF places of 82 per capita, whereas IRSD10 had the least ratio of RACF places of 9 per capita.

| IRSD | % | Ratiob | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RACF placesa (%) | People aged 65+ (%) | Within 2.5 km | Within 5 km | Overall | |

| MM1 | |||||

| 1 | 12.6 | 9.1 | 78 | 73 | 71 |

| 2 | 10.7 | 8.5 | 75 | 67 | 65 |

| 3 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 79 | 71 | 68 |

| 4 | 11.1 | 9.2 | 73 | 64 | 62 |

| 5 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 67 | 59 | 57 |

| 6 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 67 | 59 | 56 |

| 7 | 8.8 | 9.9 | 54 | 47 | 46 |

| 8 | 8.1 | 10.6 | 47 | 41 | 39 |

| 9 | 6.4 | 11.5 | 34 | 30 | 29 |

| 10 | 4.9 | 12.0 | 25 | 22 | 21 |

| MM2 | |||||

| 1 | 18.8 | 10.4 | 96 | 86 | 80 |

| 2 | 19.9 | 14.8 | 74 | 65 | 60 |

| 3 | 14.4 | 12.0 | 74 | 62 | 53 |

| 4 | 12.8 | 11.3 | 77 | 63 | 50 |

| 5 | 8.6 | 10.1 | 72 | 52 | 38 |

| 6 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 75 | 56 | 38 |

| 7 | 4.8 | 9.9 | 48 | 33 | 22 |

| 8 | 5.0 | 8.4 | 65 | 43 | 26 |

| 9 | 1.3 | 7.5 | 19 | 12 | 7 |

| 10 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 70 | 41 | 24 |

| MM3 | |||||

| 1 | 25.4 | 15.9 | 94 | 84 | 82 |

| 2 | 20.1 | 14.9 | 82 | 72 | 69 |

| 3 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 67 | 57 | 53 |

| 4 | 14.9 | 12.9 | 87 | 70 | 59 |

| 5 | 4.5 | 10.9 | 37 | 27 | 21 |

| 6 | 3.6 | 8.4 | 42 | 30 | 22 |

| 7 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 66 | 45 | 34 |

| 8 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 57 | 36 | 26 |

| 9 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 98 | 60 | 45 |

| 10 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

- Note: MM1 (metropolitan areas), MM2 (regional centers), and MM3 (large rural towns).

- a4.1% of RACF places were missing IRSD classification.

- bPer 1000 aged population.

4. Discussion

The study aimed to assess the distribution and accessibility of RACFs in relation to the aged population and socioeconomic area background across Australia’s metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns. The study found a slight variation in the spatial accessibility to RACFs across the study area. This could be related to preference for such services among older people in metropolitan areas as illustrated in recent study findings, and government reports highlight the high utilization of RACF in metropolitan areas [24, 25]. The increased utilization may also be attributed to the higher concentration of older people in these areas, as well as the migration of older Australians living in rural and remote areas to metropolitan and urban areas to be closer to their younger families. The relocation may be driven by a desire to access better quality services, avoid long wait times, or seek more comprehensive healthcare options available in metropolitan and urban areas [24]. This highlights the importance of locating RACF within close proximity to where older populations concentrate. Older people prefer to remain within their familiar communities when transitioning to RACF [20, 22, 26]. This allows them to maintain social connections, support their well-being, and facilitate family involvement. Most importantly, it ensures regular family visits, especially for spouses or older family members living in the community who may be frail and find it challenging to travel long times, even for short distances.

The study demonstrates a high distribution of RACF places within lower socioeconomic areas and declines moving up the IDRS index. A key objective of the health reforms is to improve the accessible and equitable allocation of health services. However, not all disparities in service distribution indicate spatial inequity [27]. Whether such inequalities are inequitable depends on the health needs of the affected population. This higher concentration aligns with the goal of the Australian health system to allocate resources based on people’s needs [28]. People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are at a higher risk of experiencing poor health outcomes, including increased morbidity, disability, and mortality rates. The same population tends to have a shorter lifespan compared to those from higher socioeconomic groups and tends to utilize healthcare services more. Several studies investigated the variations in health services utilization among different socioeconomic groups [27]. Generally, primary care and hospital services are accessible to people across different income levels, with a tendency to be more utilized by lower income groups [23, 29, 30]. On the other hand, specialists and dental care services are more accessible to higher income groups [17, 29]. This means that people from lower income groups utilize healthcare services more than those with higher incomes, considering differences in healthcare needs.

People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have more complex health needs due to the poor living conditions; therefore, they may need more advanced care [31]. This increases the demand for affordable advanced aged care services, which attract aged care providers to meet the needs of the local population.

The concentration of RACFs within the lower socioeconomic areas may relate to the variation in the cost of establishing RACFs across different areas. Factors such as land prices, construction expenses, zoning regulations, and infrastructure availability contribute to these cost differences, which influence the feasibility and attractiveness of such developments. For instance, in wealthy metropolitan suburbs such as Dalkeith in Perth, where the median weekly household income exceeds $4600, median weekly rent is at $802, and property values are among the highest in the country [32]. The high cost of establishment makes it more challenging to attract investors in such areas.

The Australian Government has set a target provision ratio for subsidized aged care places based on the population aged 70 years and older. This ratio aimed to provide 72.8 operational aged care places per 1000 to those aged 70 and older. In the May 2023 Federal Budget, this target was revised to 60.1 places per 1000 for the same target group [33]. Yet, the available places do not accommodate the current demand for such services, as reflected in the long wait time for a placement. According to the 2024 Productivity Commission Report, the median wait times increased by 67%, from 40 days in 2012-13 to 135 days in 2023 [31]. Nationally, in 2023, only 59% of applicants were admitted within less than 9 months [25]. Not to mention the shortages of workforce and closure of these facilities. Due to workforce shortages in the aged care sector, many RACFs were unable to operate at their full capacity, which resulted in a decline in the reported occupancy rate to 86% in 2023 [34]. This decrease in occupancy does not reflect a lack of demand; in fact, many RACFs have extensive waitlists. In the final quarter of 2022, 13 residential providers exited the sector, with workforce shortages reported as a key reason for these closures [34].

The shortage of available places may prompt older people who are unable to live independently to utilize other aged health services or remain at home, potentially receiving insufficient health services to meet their specific needs. This, in turn, may contribute to poor health outcomes, an increase in emergency room presentations, and unplanned hospital admissions. The lack of available places may affect the hospital system. In 2022-21, patients who were waiting for residential aged care occupied 286,050 patient days in hospitals nationwide [31]. These individuals no longer require hospital services and are unable to be discharged because they are waiting for placement in a RACF, which may create what is known as “bed blocking,” adding undue pressure to the already strained healthcare system [35]. The extended stay can contribute to adverse patient outcomes such as falls or infections, create considerable burdens on hospital resources, and create financial pressures for the healthcare system. In 2020-21 alone, between $316.7 million and $847.6 million in health costs were estimated for those waiting for placement in residential aged care [35]. This figure may increase with the shift towards aging societies and the growing prevalence of frailty and dementia among older people and worsen with the absence of inadequate RACF places.

Analyses of this kind provide insights into the current accessibility of RACFs to the aged population and inform policymakers of accessibility challenges. This trend highlights the urgent need for expanding and allocating additional RACF places, ensuring their equitable distribution to effectively meet the demands of the rapidly aging population. The aged care sector faces a sustainability crisis that requires a substantial increase in government funding to stabilize and grow the industry. According to the Federal Department of Health and Aged Care, 53% of all aged care facilities operate at a loss [34]. This prevents providers from investing in their workforce, productivity improvements, and expanding or investing in new facilities. The biggest obstacle for providers to maintain operational viability and ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality care is attracting and retaining a qualified workforce. Despite a recent 15% increase in wages for aged care workers, compensation remains insufficient to prevent skilled workers from seeking higher-paying jobs in other industries [34, 36]. This wage disparity challenges the sector’s ability to maintain a stable workforce, which is vital for delivering quality care and preventing closure.

Health authorities and policymakers should concentrate on several key areas to enhance the accessibility and sustainability of RACFs. The sector requires increased funding and financial support to help facilities remain operational and encourage new developments, particularly in underserved areas. Enhancing workforce capacity is an integral part of the sector’s sustainability. This can be achieved by increasing wages and offering incentives to attract and retain skilled workers, investing in training programs to guarantee high-quality service provided for both staff and residents, and investing in technological innovations to ease pressure on the workforce, which enhances the overall experience and contributes to a more pleasant and efficient environment within RACFs.

4.1. Strength and Limitation

The study contributes to the growing literature focussed on the issue of aged health accessibility and serves as a baseline for future studies. The study analyzed the most recent and reliable census data publicly available. Data were aggregated to provide an overview of distribution at the area level. This aggregation may lead to misleading conclusions when applying the result to the individual level. The census data can become outdated due to the rapid increase in the aged population, migration patterns, and changes in socioeconomic profiles. The findings highlight the importance of considering geographic context and local needs when examining healthcare access to identify gaps in aged health provision. The study’s assessment did not extend to evaluating the availability of vacant places or occupancy rate, and it mainly focussed on the capacity of RACFs (the number of places for each facility) due to data availability. Future studies are needed to examine the occupancy rate of each facility to indicate the over/undersupply of facilities across Australia. This will assist policymakers and health authorities to allocate and distribute resources effectively.

5. Conclusion

The study highlights the shortages in the distribution and availability of RACF places across Australia’s metropolitan areas, regional centers, and large rural towns. Addressing these disparities is imperative to ensure that the aged population can access RACFs regardless of their geographic location and socioeconomic backgrounds. The aged health system needs increased funding, improved workforce conditions, and equitable resource allocation to create a sustainable aged care system with a high-end quality of care. This study focussed on the capacity of RACFs; future examination of RACF occupancy rate is needed to indicate the over/undersupply of facilities in certain areas. Further investigation of other aspects of accessibility, such as affordability and acceptability, is essential to gain a better comprehensive understanding of all dimensions of accessibility to guide policymakers to ensure equitable aged health provision across Australia.

Ethics Statement

Ethics exemption was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Australia since the data were obtained from open access and publicly available sources (2024/ET00182).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Amal Musleh Alrewaithi: designed the study, collected data and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Marc Tennant: designed the study, collected data and analysis, reviewed results, and final manuscript. Estie Kruger: designed the study, reviewed results, and final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge King Saud University and the University of Western Australia for ongoing support.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available upon request from the corresponding author.