“Good Luck Out There Without NDIS”: Challenges Accessing Individualized Support Packages by Autistic Young People Leaving School

Abstract

Introduction: The transition from schooling to adulthood is an important and complex time in a young person’s life, especially when they have a disability. For young autistic people, it is critical to receive the right support to ensure a successful transition. In Australia, disability supports are provided by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a scheme implemented and administered by the Australian Government (specifically the National Disability Insurance Agency [NDIA]) since 2013. Implementation of Australia’s NDIS has been inadequate in supporting the needs of many autistic young people. Autistic people are the largest group of participants in the NDIS. Support for this group is important considering the significant investment involved in the provision of NDIS funding, coupled with the potential negative consequences if they are not well-supported. This study explores the experiences of key stakeholders in relation to young autistic school leavers and their challenges accessing NDIS Tier 3 individualized support packages.

Method: This study adopted a qualitative methodology using a constructivist paradigm. This study draws on the perspectives of four key groups: young autistic people, parents/carers, educators, and disability service providers. Reflexive thematic analysis of the interview data was conducted.

Findings: Two overall themes were identified. The first theme was related to fighting to get access to the NDIS, encompassing subthemes related to the NDIS maze, a heavy emotional and practical toll as well as inconsistencies in access. A second theme highlighted a worry for the future if autistic young people did not receive the support they needed postschool. Findings highlighted a range of difficulties accessing individualized funding packages (Tier 3) for autistic young people. There has been a critical failing of service provision at “Tier 2” of the NDIS (also referred to as information linkages and capacity building or foundational support), which was intended to facilitate access and participation in mainstream community services for people with disability. This placed additional pressure on Tier 3 and exacerbated the toll that interacting with the NDIS took on participants.

Conclusion: Urgent work is needed to ensure that systems within the NDIS are funded appropriately and operating as intended to ensure good and equitable outcomes for autistic people leaving school.

1. Background

Transition from secondary school to postschooling and emerging adulthood is a distinct and potentially challenging time in a young person’s life [1]. Emerging adulthood brings with it a greater focus on independence, work roles, and tertiary education and is a key time for identity exploration and development [2]. Young people often experience a shift in social relationships, with a transition away from parental involvement and support [1, 2]. However, early emerging adulthood varies depending on individual circumstances [1], and young autistic young people can experience more difficulties during this time than their nondisabled peers [3, 4].

Autism spectrum disorder (hereafter autism) is a lifelong pervasive developmental disability characterized by differences in social communication, repetitive behavior, and restricted interests [5]. However, there is wide heterogeneity observed in autistic individuals [6] who present with varied strengths, skills, and challenges and autism is often described as a “spectrum” to reflect this diversity [7]. Recent estimates of autism prevalence have shown an increasing trend and have proposed that autism may impact 1 in 59 children [8], with current estimates as high as 1 in 36 children in the United States of America [9] and 1 in 150 in Australia [10]; however, estimates can vary across countries depending on how and when prevalence data were collected and variable identification practices. Autism has often been defined using a biomedical or deficit-based approach. However, recent literature has emphasized the role of societal beliefs, institutions, and systems in contributing to difficulties faced by autistic individuals [11].

Transition to life after school presents particular challenges for autistic young people, who commonly experience difficulties and restrictions in academic and nonacademic pursuits during their schooling journey [12]. Autistic people experience more difficulties in gaining and maintaining employment than their nonautistic peers [13] with a higher number of autistic individuals being unemployed or underemployed [14]. They may experience poorer work satisfaction and poorer working conditions, making it less likely that they would remain employed [15]. Autistic people also experience poorer health and wellbeing [16] and more barriers to healthcare [17] impacting their overall capacity to participate in the community and succeed in adult life.

Despite these known inequities, autistic people exhibit many strengths including a high intellectual capacity for some autistic people [18] and strengths in visual processing [19] and technology use [20] and can have good outcomes postschool, if they are well-supported [21]. Supports vary depending on the needs of the individual and can comprise environmental modifications to support participation in employment [3], as well as tertiary education supports [22], supports for social participation [23], daily living skills [24], and family supports [25]. The neurodiversity movement emphasizes that supports designed to build autistic people’s positive self-identity and address environmental barriers to participation, such as bullying and exclusion, are vital to improving mental health outcomes [26].

The identified support needs of young autistic school leavers coupled with the knowledge that good support can facilitate a positive outcome necessitate an equitable efficient support system. In Australia, disability supports are provided by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a scheme implemented and administered by the Australian Government (specifically the National Disability Insurance Agency [NDIA]) since 2013. The NDIS was designed in response to what was described as a flawed and unsustainable disability sector which had failed to meet the needs of people with disability [27, 28]. The NDIS offered a new way forward for disability supports, which proposed to increase choice and control through a three-tiered system, bringing disability supports under one “umbrella” [29]. Tier 1 was designated as a nationwide “insurance scheme” which would guarantee disability support in the event that any Australian ever needed them [29]. Tier 2 was intended to provide information and referrals to mainstream and community support to all Australians living with disability and their carers, with the goal of supporting their inclusion in society. Tier 3 of the NDIS comprised the provision of individualized funding packages to certain individuals with a disability, provided they meet the criteria of lifelong permanent disability requiring support in daily life [30]. An individualized funding package grants people funds for reasonable and necessary supports [27] to facilitate the participant to live an “ordinary life.” Supports funded under the NDIS can include help with community, accommodation, employment, provision of equipment, and home modifications as well as funding for therapies such as occupational therapy, speech pathology, and psychology [31]. While the NDIS provides the funding, the scheme is designed around a “market” system where a person may use their funding to pay for the services at a private or not-for-profit service provider of their choice [27]. There are large numbers of NDIS participants who report that their NDIS individualized funding packages are fit for purpose and meeting their needs [32]. However, this is not the case for all NDIS participants and there are many people with disability who have not been able to secure an individualized funding package from the NDIS at all. The experiences of autistic people trying to access the NDIS, especially those transitioning out of school, have not been presented in the research literature.

Individualized funding packages granted under the NDIS as part of the three-tiered system were never intended to fund support for every Australian with disability [29]. Tier 2 was planned to provide community-based mainstream support, upskilling the community at large to be more inclusive of people with disability with the aim of increasing their participation in mainstream society, including schools, workplaces, health services, sports clubs, culture, arts, and religious activities among others [27, 29]. Increasing the capacity of community-based mainstream services to be more universally accessible has been proposed as a key intention of the NDIS [33] and a potential means of reducing the reliance on segregated disability services and supports. The critical importance of inclusion of people with disability into mainstream communities was highlighted in the Final Report of the recent Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation of People with Disability [34], across various key areas such as education, work, and housing. However, capacity building of mainstream services planned under Tier 2 has been significantly underfunded, resulting in many people with disability not being able to access mainstream support [29, 35]. A recent review of the NDIS has highlighted the inadequacies of funding and supports provided under Tier 2 (referred to as “foundational supports”) [36]. Tier 2 has not achieved its aims, creating a significant lack of services in the community, which may entrench marginalization, exclusion, and hardship [35, 37]. Lack of funding and resources provided at the Tier 2 level, and subsequent inadequate mainstream supports, has left people with disability viewing individualized funding packages as their only option to gain support [35, 37]. As a result, the costs of individualized funding packages have exceeded estimates set forth within the design of the NDIS, with speculations that the scheme may become financially unsustainable [38].

There has been an overreliance on the individualized funding component of support packages, and the provision of these packages to NDIS participants has been potentially inequitable [39]. Prospective NDIS participants have reported a need for personal advocacy to ensure their support needs are met [39]. Certain groups have experienced more difficulties in accessing the NDIS including those from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds [21], women with disability [40], First Nations Australians, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds [39], and people with “invisible” disabilities [41]. There are limited studies reporting specifically the experiences of autistic people in relation to NDIS access. A recent study by Clark and Dissanayake [42] suggested that parents of young autistic children (aged 1–3.5 years) accessing the NDIS experienced greater levels of stress; however, no studies were located which considered NDIS access for young autistic adults. Barriers to NDIS access include the cost of necessary assessments to prove the impact of one’s disability [39], the person’s own capacity to plan and set goals [43], the administrative burden [39], and knowing the “jargon” to use to facilitate access [30]. These issues undermine the intention of the scheme, which was to provide choice and control for all people with disabilities in meeting their own personal goals [30] and to rectify the inequities present in the Australian disability sector prior to the implementation of the NDIS [27].

Identification of autism has been increasing in recent years and autistic people are the largest group of NDIS participants [44]; therefore, their perspectives are important. In addition, adolescents and young adults with a disability have been highlighted as a particular group in need, with a large discrepancy observed between them and their peers without disability [36]. With limited research on the specific needs of young autistic adults, it is critical that issues for this population in relation to NDIS access must be explored. This paper focuses on the experiences of a particular group of young autistic people who have had difficulties accessing NDIS individualized funding packages to support them in their transition to adult life.

The objective of this study is to explore young autistic peoples’ transitions from school to adulthood, with a focus on those who had difficulties accessing NDIS individualized support packages (Tier 3). This involved gathering the perspective of a range of stakeholders who have experience with this phenomenon including young autistic people, carers, educators, and disability service providers.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study included 45 semistructured interviews with four key groups of stakeholders including young autistic people who were interviewed at two or three timepoints throughout the study and carers, educators, and service providers who were interviewed at one time point only. A qualitative design was adopted for this study which followed a constructivist paradigm, designed to understand the construction of reality from participants’ perspectives [45, 46].

This study received ethical approval from Western Sydney University and New South Wales Education (State Education Research Approvals Procedure [SERAP]) prior to participant recruitment.

A paid advisory committee of stakeholders was engaged in this study. This included young autistic adults and industry professionals who were engaged at key timepoints throughout the research process. They met four times throughout the course of the study and advised on recruitment strategies, contributed to the development of the interview guide, provided feedback on preliminary and final data analysis, and advised on the most appropriate methods of dissemination of findings [47]. In addition to engaging an advisory committee, one of the lead researchers and authors for this paper (NS) is also autistic.

Following consultations with the advisory committee, identity-first language was adopted for this study. This is also in line with the current preferences of the autistic community [48]. However, there is a lack of consensus in disability naming. Generally, preferences of the autistic community may not generalize to other disability groups. Therefore, person-first language is adopted for nonautistic disability groups [49].

2.2. Participants

This study recruited 39 participants as part of a larger study which explored autistic young peoples’ transitions from school to adulthood, from the perspective of key stakeholders (see Table 1). Four participant groups were recruited including young autistic people who had recently left school or who would leave school in the next two years (aged 16–25) (n = 10). The young people had varying levels of support needs. All were recruited from mainstream schools, and there were no specific inclusion criteria related to a young person’s intellectual or verbal abilities. Other groups recruited included parents and carers of young autistic school leavers (n = 9); educators within the school system who supported autistic students in their final 2 years of high school including classroom teachers, transition support teachers, head teachers, careers advisors, and learning support officers (teaching assistants) (n = 14); and disability service providers who supported young autistic people who had recently transitioned out of school (n = 6). Carers and young people were not recruited as “dyads.” However, some carers were connected to participating young autistic people. This study initially set out to recruit young autistic people and parents/carers who were not accessing the NDIS in their transition from school into adulthood. This particular group was chosen as a focus for the larger study in light of concerns about how their support needs may be met in the absence of NDIS–funded postschool support services.

| Participant group | Interactions with the NDIS |

|---|---|

| Autistic young people (n = 10) | |

| YP1 | Successfully gained an individual funding package after rejection (young person of C2) |

| YP2 | No access but planning to apply |

| YP3 | No access (young person of C6) |

| YP4 | No access and do not plan to apply |

| YP5 | No access |

| YP6 | No access but plans to apply and has started the process but needs support |

| YP7 | No access |

| YP8 | No access and have decided not to apply (young person of C3) |

| YP9 | No access but works in the disability sector, so has interacted with NDIS professionally |

| YP10 | No access and has not applied (young person of C4) |

| Carers (n = 9) | |

| C1 | Was in the process of applying for the NDIS for their young person, also worked professionally in disability |

| C2 | Has applied and was initially rejected but then successfully gained access for their young person (parent of YP1) |

| C3 | Plans to apply and is getting the application together and has currently been privately paying for the services (parent of YP8) |

| C4 | Has not applied yet but believes their young person may be eligible and has begun preparing an application (parent of YP10) |

| C5 | Had applied and was initially rejected, but then successfully gained an individualized funding package |

| C6 | Is not currently accessing NDIS supports (parent of YP3) |

| C7 | Had applied for young person, was rejected |

| C8 | Had applied and successfully gained an individualized funding package for their young person |

| C9 | Is not currently accessing NDIS supports |

| Educators (n = 14) | |

| E1 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools) supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support |

| E2 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools) supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support |

| E3 | Head teacher is not directly involved in supporting families and young people to access NDIS |

| E4 | School learning support officer (teaching assistant) provides classroom support but has no direct involvement with NDIS access |

| E5 | Head special education teacher in mainstream school works with students who do and do not have NDIS packages |

| E6 | Special education teacher in mainstream school is not directly involved in supporting NDIS access |

| E7 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools) supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support school transition teacher (covers multiple schools) |

| E8 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools) supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support school transition teacher (covers multiple schools) |

| E9 | Special education teacher has supported families and a family member with NDIS application |

| E10 | School learning support officer (teaching assistant) provide classroom support but has no direct involvement with NDIS access |

| E11 | Head teacher oversees students with disability, some of whom have NDIS packages |

| E12 | Careers advisor has minimal involvement with NDIS–eligible students |

| E13 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support school transition teacher (covers multiple schools) |

| E14 | School transition teacher (covers multiple schools) supports young people and families with NDIS access as part of transition support |

| Disability service providers (n = 6) | |

| SP1 | Registered NDIS provider and parent of a young person with a disability |

| SP2 | Registered NDIS provider |

| SP3 | Registered NDIS provider |

| SP4 | Disability employment support provider, serves young people who do not have NDIS access |

| SP5 | Disability employment support provider, serves young people who do not have NDIS access |

| SP6 | Disability employment support provider, serves young people who do not have NDIS access |

- Abbreviation: NDIS, National Disability Insurance Scheme.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were recruited through multiple channels including social media; disability provider networks and organizations; direct mailouts to schools, tertiary education providers, and disability employment services; and snowball sampling. Participants contacted researchers and gave their written informed consent for their participation. Where autistic participants were under the age of 18, they gave their written and verbal assent, and their parents gave written consent. Interviews were held following the completion of the consent process.

Semistructured interviews were conducted with participants either individually or with another participant when requested. For example, young people and their parents requested to be interviewed together at times. Semistructured interviews were conducted either in person or via Zoom, totaling 2395 min, with an average length of 53 min per interview, across 45 interviews. Interviews with young autistic people themselves totaled 1133 min across 22 interviews, ranging from 13 to 138 min, with an average of 51 min per interview. Two of these interviews also included the person’s parent; the rest were conducted individually. For the other participant groups, interviews ranged from 13 to 90 min in duration, averaging 53 min per interview. Semistructured interview guides were developed for each of the stakeholder groups and were created in consultation with researchers and the project’s advisory committee to ensure that questions were asked in an affirming way and would allow researchers to answer the research questions posed [50]. Questions were focussed on stakeholder perspectives of the experiences of young autistic people in relation to being in high school, getting ready to leave, and the support they received or required, including the NDIS. Postschool goals and aspirations were discussed as well as the enablers and barriers to achieving these.

2.4. Data Analysis

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Transcripts from interviews were analyzed in NVivo using a reflexive thematic analysis approach as described by Braun and Clarke [51]. This approach allows systematic identification and organization of themes identified within the data. A deductive approach was adopted in terms of identifying and grouping information from across the four participant groups which related to the specific phenomena of interest, namely, perceptions and experiences of the NDIS. Data related to the NDIS from all participant groups were analyzed using an inductive approach where researchers generated themes from the data.

Participants and their experiences with the NDIS are presented in Table 1. Most young people were considering NDIS access, with one successfully gaining access following rejection. Two carers had current NDIS access for their young person, one following rejection and another having been rejected and planning to reapply. Five participants from the young autistic people and carer groups were planning to apply for packages to support their young person and were in various stages of the process.

Reflexive thematic analysis took place in six stages [51]. First, transcripts from each stakeholder group were read several times by at least one member of the research team in order to familiarize themselves with the data. Detailed notes were taken by researchers at this time around observations of initial trends. Initial coding took place for each stakeholder group separately and these codes were used to develop preliminary themes. Researchers then met to discuss and compare initial themes numerous times to further develop and refine themes across the four groups collectively. Consistent with the research objectives, the analysis did not seek to compare the perceptions or experiences across the stakeholder groups. Following initial theme development, further refining took place and particular themes were drawn out in relation to the research questions. For the purposes of answering the research aim specifically in relation to the NDIS, each initial code for each stakeholder group was reviewed for relevant information related to the NDIS, revising the initial codes and excluding those not relevant. In addition, each transcript was carefully reviewed for additional information in relation to the NDIS and codes and themes were further revised. Here, themes from each of the stakeholder groups were collapsed together and fine-tuned in order to answer the research aim. Analysis was reviewed by members of the research team independently and in discussion with the lead author. From here, narratives, supported by participant quotes, for each theme were drafted, reviewed, and corroborated by the research team members before being finalized.

The positionality of researchers was considered during this project as it relates to the perspectives and experiences of researchers in relation to the disability sector and the NDIS. Researchers who led the data analysis were three registered health professionals who all had 15 or more years of experience working in the Australian disability sector in varying capacities including as health practitioners, managers, advocates, researchers, and tertiary educators. One of the lead researchers (NS) was diagnosed as autistic in adulthood, while the remaining two researchers (CM and DT) do not identify as having a disability. Two of the authors (CM and NS) have had professional experience as occupational therapists supporting autistic people and their families who were accessing or attempting to access individualized funding packages through the NDIS. The past experience of the researchers in relation to the topic of interest is viewed by Braun and Clarke [51] as a resource for data analysis, facilitating their active role in producing knowledge, rather than positioning it as a bias.

3. Results

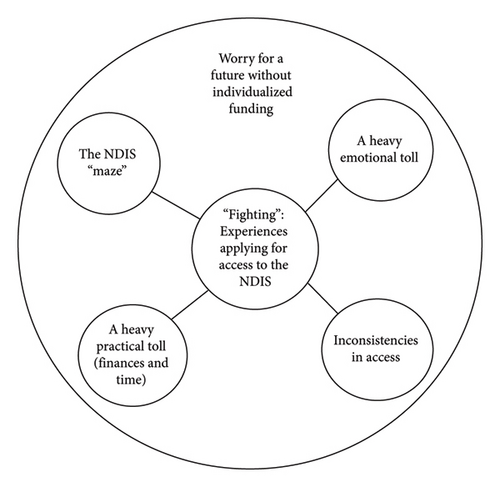

Two themes, encompassing four subthemes were generated through thematic analysis in relation to autistic young people accessing the NDIS as reported by the four stakeholder groups. The first theme was related to participant experiences of fighting to gain access to the NDIS. Within this theme, there were four subthemes. The first was related to navigating the NDIS being perceived as a maze. The second subtheme was related to the heavy emotional toll that attempting to gain access took on participants, with the third highlighting the heavy practical toll in terms of time and cost. A fourth subtheme was about experiences of inconsistency of access. A second theme was identified in relation to worry for the future without access to individualized funding. See Figure 1 for a thematic map. The second theme of worry is conceptualized in the map as surrounding the first theme of “fighting.” The “fighting” is influenced by a worry for the future without appropriate support.

3.1. Theme: “Fighting”: Experiences Applying for Access to the NDIS

3.1.1. Subtheme: The NDIS “Maze”

The application process for the NDIS was conceptualized as a “maze,” with navigating the process variable and difficult for many participants. This was cast as a key barrier to accessing support required to bolster the key developmental milestone of transitioning from school to postschool. Service providers and educators frequently commented about their experience with the NDIS “maze,” which is not surprising given their viewpoint encompasses watching many families apply. Navigating successfully through the NDIS “maze” had been achieved by some participants in knowing the right language to use to gain a favorable response from the NDIS. Young person speculated about what may be needed to facilitate access, stating that it was “common knowledge” among people with disability that: “you have to make it (your disability) sound worse than it is” to be successful in accessing the needed supports. Similarly, Service provider 1 described the need to “massage” the information to “fit” the young person into rigid NDIS’ categories to successfully navigate through the “maze” to access funding: “…we’ve got to get funding somewhere. And if we could massage it to look like it’s under respite or community services or something that doesn’t quite fit. But as long as it can get approved, that’s what the service provider would do.” Educator 8 expressed the importance of knowing the “right’ language” to use: “But if you don’t have the language or you don’t know the categories and what falls under the categories, you know…”

Participants also reflected that navigating the NDIS “maze” was more difficult for some participants because of their circumstances, highlighting where intersectional disadvantage may have been at play, placing people at a further disadvantage. For example, participants reflected on the difficulties for families who were culturally and linguistically diverse: “I spoke to her mum. She’s full Vietnamese speaking background and I doubt that she would understand anything about this process if I’m struggling with it” (Service provider 1). Carer 1 echoed this: “It concerns me about the parents that are not as strong in English. So they probably get left behind…”

Service provider 3 perceived that the “lack of information surrounding NDIS is the biggest fault.” This was cast as a key flaw in gaining access to the much needed support for transition to postschool for autistic young people. They went on to say that as the NDIS has expanded it had “turned into a system that’s a maze within itself.” Service provider 5 who had been involved with the NDIS for at least 5 years expressed that: “there’s a mass of information out there” (about the NDIS) but went on to highlight that getting access to the right information was the major challenge. Educator 9 echoed this sentiment describing the NDIS application process as “really, really hard. The language that is used. It’s not accessible.” Educator 7 similarly said: “that’s the madness of how NDIS often frame their letters. They’re not very easy to understand, even if you’ve got good English.”

Similarly, Service provider 2 described their experience of families attempting to access a support person at the NDIA to help them with the application for funding to support critical postschool support for their young autistic person. They perceived there was a lack of knowledge among NDIA staff: “multiple people at the NDIS don’t seem to know the job very well and it gets confusing…But those families who are calling the NDIS for the very first time, they’re expecting that someone’s going to know what they’re talking about…and they don’t.” Furthermore, this participant highlighted that “if you go on the NDIS website and read through, you know, people are confused.”

The same service provider also stated that “it’s actually quite a simple process when you understand it, you know,” highlighting again the inequity in the experience of applicants, with experiences largely depending on one’s capacity to successfully navigate the NDIS “maze.”

Participants also speculated that difficulties with NDIS access were a deliberate cost-saving strategy by the NDIA in order to curtail the number of people accessing the scheme. Service provider 2 perceived that: “The NDIS has become about saving as much money as possible.” Service provider 3 echoed this: “…it’s almost like government doesn’t want them (people with disability) to access (the NDIS).. Service provider 2 also conceded that NDIS access restrictions may have been related to past “abuses of it (the NDIS)… they’ve had to rein it in…” Overall, difficulties and confusion experienced by participants were a concern, as not being able to navigate successfully through the NDIS “maze” may mean a young autistic person would be denied the NDIS individualized funding supports they needed for postschool transition.

3.1.2. Subtheme: A Heavy Emotional Toll

Many participants reported that the experience of attempting to gain NDIS access took a heavy emotional toll, particularly for those who were parents or carers of young autistic people. The toll taken was described by participants as being an emotional burden, which served as a barrier to accessing the support that young autistic people needed for a successful transition out of school. Carer 8 described the process of gaining NDIS access as emotionally taxing, explaining: “laborious and intrusive…. I remember one interview I was interrogated and had to relive all these really traumatic experiences…. I just remember being in tears during a meeting with this panel and thinking well that’s not very safe… to upset carers to that degree, and not to have any follow-up, just felt a little bit unethical and unsafe.” This aspect of the “emotional toll” positioned the process of gaining access to funding support as potentially traumatizing and unsafe for prospective participants, who were required to recount difficult past experiences as a necessary process to gain access.

Carer 3 described the heavy emotional toll of attempting to gain access to individualized funding to support postschool transition, which at times felt insurmountable and as such they did not continue trying: “I’m literally head butting my head against a brick wall… I’m sick of it and now it just sits in the bag on the floor, and I don’t do anything about it…” Young person 2 echoed that describing the “daunting” nature of the paperwork required: “It’s just all the information was, like, I just felt I was way in over my head.” Other participants described the process as “very complicated” (Carer 1) and a “battle” (Educator 7). Service Provider 4 described their experience of supporting young autistic people and their parents who had been rejected from the NDIS as follows: “The looks on their faces, especially their parents, they’re gutted. It’s just like they’ve gone through the mill trying to get something going for the young person…” After being rejected, families were left with inadequate support they would need for a successful life after school.

Negative experiences of the emotional endurance required to apply for support under the NDIS were expressed by several participants, who perceived that this prevented people from even applying: “Some people see the NDIS as just a big mountain to climb, too hard (Educator 14).” This heavy emotional toll of seeking access to the NDIS was identified across participant groups. Seeking access was perceived to be distressing for autistic young people and carers in particular, who at times were left to worry about the prospect of a future postschool, with inadequate support.

3.1.3. Subtheme: Heavy Practical Toll (Finances and Time)

In addition to the heavy emotional toll, participants also described a more practical burden of accessing an individualized funding package from the NDIS to support postschool transition in terms of administrative requirements, costs, and time. Echoing a recurrent sense of needing to “fight” young people and carers described that getting access to the NDIS “takes forever” (Carer 3) and requires being “persistent” and “pushing”: Carer 7 said: “Look, the NDIS thing… I might just have to bite the bullet and have another go at it, but, yeah…You obviously need to be pretty persistent to get anywhere.” Young person 2 described that they wanted NDIS support to help them find a job, but “it’s taking such a long time to approve it.”

An autistic young person (Young person 8) described the time and expenses involved in seeking NDIS access: “…it takes forever, even though it’s supposed to help it takes forever for anyone - - - and it costs so much money just for you to get basically no money …just to get a little bit help just so you can function like everyone else.” Carer 2 also stated that the assessments were prohibitively expensive when attempting to gain an individualized funding package for their young autistic person: “I was trying my hardest to get him on the NDIS, and at the time as well I’m being told to get him tested was going to cost $3–4000, which I didn’t have.” This additional burden of costs and time was perceived by participants as exacerbating the difficulties in accessing NDIS funding for autistic young people to be supported in their transition out of school.

3.1.4. Subtheme: Inconsistencies in Access

Many participants described inconsistencies in accessing individualized funding under the NDIS. Many participants perceived that they needed to “get lucky” to gain access to the right support for postschool transition. This involved “luck” in finding the right support professional to help them, or “luck” with having the right resources or capacity to find a way through the process themselves. The concept of “luck” as presented by many participants illustrated a perception that NDIS individualized funding packages (Tier 3) were not provided in ways that are consistent or fair. For example, Young person 1, who eventually gained access to a NDIS package after a “long fight” described the vital input of a particular professional who supported them to get access: “She [the professional] helped me. She got me through everything that we needed…this was a great relief after previously being denied access twice and after an entire year of Mum fighting and constantly submitting.” signaling that access was inequitably driven by the type of support you could obtain to apply.

Similarly, Carer 5 said “…we were lucky that we had this nurse that knows a social worker… the nurse was very understanding and she was able to organize the social worker to help us fill out this, arrange some accommodation for him and NDIS.” Carer 7 also described a process of luck, but related this luck to their own capacity to push through with the process of attempting to gain access: “…when I have the capacity to, I chase things down, so that has resulted in us being quite lucky in some ways. But the system shouldn’t be built around people just getting lucky, working their butts off to try and make things happen, and then just getting lucky.”

In contrast, Carer 2 described the experience of not being so lucky when they interacted with an unhelpful health professional when attempting to gain NDIS access for their young person: “He (the professional) didn’t know him (the young person) at all, and he even said to me ‘He’s not going to get on the NDIS’ and I’m like, you don’t even know (young person). You don’t know what we’ve been through his whole life…”

Two different educators described varied experiences of working with Local area coordinators (LACs). These are trained professionals within communities who are charged with the task of supporting people with disabilities to gain access to appropriate funding packages or supports under the NDIS. They described a mix of successful and unsuccessful experiences and interpreted this discrepancy as lucky or unlucky depending on the LAC they happened to connect with. This resulted in an access process which was inequitable. Educator 9 described: “I’ve been lucky. We’ve had good LACs but I’ve had families that haven’t had good LACs and I think that is the biggest problem. If somebody who is there on the frontline doesn’t know what they’re doing or has prior opinions or that kind of thing, that I think is a real issue.” This was echoed by Educator 7: “we’ve already seen that you could hand in the same evidence to two different NDIA [representatives], and you’ll get two different outcomes.” Inconsistencies in access experienced across participant groups were characterized by many participants in relation to “luck.” These differing conceptualizations of “luck” serve to highlight the inadequacies of the NDIS system. When attempting to gain access, it appears that hidden prerequisites exist in relation to a person or family’s own resources, capacity, or appropriate support people to guide them successfully through the process of gaining access, and this was a driver of perceived inconsistencies.

3.2. Theme: Worry for a Future Without Individualized Funding

Tier 3 individualized funding packages from the NDIS were perceived by several participants as the only place to access disability support after a young autistic person left school. This positioned access to a Tier 3 NDIS individualized funding package as “high stakes” in terms of getting the necessary funding support that young autistic people may need in the future, as they transition out of school to their adult lives. One young autistic person described that NDIS access was important to be “able to provide support and capacity building and helping people meet their goals and things…” (Young person 9). Young person 2 echoed this, saying they needed NDIS support “because I don’t think I would do that well on my own.” Many participants perceived that no access to NDIS equated to no access to support. One young person expressed that: “I wasn’t able to be recommended for things, because I didn’t have NDIS funding.” (Young person1). Young autistic participants perceived that accessing a NDIS individualized funding package would open doors to support that would help them postschool.

This perception was also widely held by educators who expressed worry about gaps in service provision for young autistic people who were leaving school and would be left with limited or no services if they were denied access to NDIS individualized funding packages. Educator 5 expressed their concerns: “this is where that gap is out there for those kids that don’t have that NDIS, and who are we going to rely on?” Educators perceived that without NDIS funding, there would be nowhere else for autistic school leavers to get support once they left the structure of schooling. The future would be “pretty grim” (Educator 9), with young autistic people being “left behind… left out of the conversation” (Educator 1).

When a young autistic person was denied access to the NDIS, especially at this critical transition period of moving out of school, various stakeholders perceived that negative consequences would result, impacting the person’s future success. Carer 3 described the perceived impact on their young person’s future independence: “we’re not trying to cheat anyone, I want to have (young person) set up so that she can continue to get the help that she will need going forward - - - when she becomes an independent person.” Similarly, Service provider 6 explained how not having a NDIS individualized funding package was a barrier to gaining employment and independence following school: “…life skills, like, he can’t read his payslips…Learning how to cook meals at home and pay bills. He doesn’t know how to read and write, so he can do his job…I think, with a NDIS plan to help him with all of those things and if he was able to move out of his parent’s home and live on his own, he would be much happier at work.”

Similarly, other participants perceived that not having access to NDIS funding after school meant that necessary practical on-the-job support and practical support to succeed in tertiary education were not available, significantly limiting future opportunities for the young people they supported. For example, Carer 7 described the lack of NDIS access as a “blockage”:

“We tried to get NDIS, and he was rejected.… We were trying to get it mostly because the school had said transition support would be really useful for him (young autistic person), whatever he’s doing, and it’s quite specialized and all that stuff… I’m not asking for money. I’m asking for access to specialist services.”

Educator 11 highlighted specific concerns of not being able to access school leaver employment services (SLESs) without a NDIS individualized funding package. SLES is a package of supports designed for young people requiring extra support to build individual and work readiness skills to help transition to the workforce: “So when we say goodbye – as far as I’m aware it’s kind of like good luck out there without NDIS” (Educator 11). Participants across stakeholder groups expressed worry for a “grim” future for autistic young people if they did not receive the right funding, and therefore the right support, to succeed in life after school.

4. Discussion

This study captured multiple stakeholder perceptions of young autistic people’s experiences around trying to gain access to NDIS funding packages to support the transition from school. Overwhelmingly, findings indicated a negative perception of NDIS processes to access an individualized funding package. For the young people and carer participants, many experienced difficulties in accessing the NDIS; thus, their negative perceptions are not surprising. These perceptions, however, were reported across all stakeholder groups. The themes encompassed the experiences of participants “fighting” to gain access to the NDIS. This included subthemes related to navigating a maze, a heavy emotional and practical toll and inconsistencies in access. A second theme revolves around worry for the future if young autistic people were unable to gain access to NDIS funding at the critical developmental stage of transitioning to adulthood.

A key finding is that the process of accessing NDIS individualized funding packages may exacerbate inequity. There are numerous drivers of this inequity including divergent individuals or family’s own capacity or their access to the right support people and resources to navigate through the “NDIS maze” to gain access to funding and support that they need for life after school. This finding highlights inadequacies in Tier 3 of the NDIS, whereby vulnerable applicants may experience further disadvantage. This finding is in agreement with other literature which has reported inequity in NDIS access. A national survey of over 700 respondents by Yates and Dickinson [52] reported that some families had more capacity to navigate the administrative systems of the NDIS on behalf of their young person, and that better advocacy skills correlated with a better outcome for the family. This reliance on family capacity in accessing the NDIS can exacerbate inequities. A systematic review by Russo and Brownlow [53] echoed these inequities when parents were required to navigate NDIS access without any support from the NDIA. It was reported that NDIS access was overly complex and difficult to navigate, contributing to the stress experienced by families. A large study by Devine and Dickinson [41] interviewed over 100 people with psychosocial disability and their carers about NDIS funding packages. Findings highlighted that participants perceived that they “got lucky” in getting access to the right support. No previous studies were located which specifically considered the experiences of autistic school leavers who experienced difficulties with NDIS access. The present study provides a unique contribution around the challenging experiences during this key development stage of transition to adulthood.

It is possible that the inequities observed in the present study are born out of the design of the NDIS itself. While the NDIS positions itself as offering “choice and control” to participants, there is an assumption that people with disability can make choices and advocate adequately for their own needs [33]. The present study observed differences in the resources and capacity of participants to do this. This is in line with the findings which have reported difficulties for particular groups including women [40] and people from CALD backgrounds [41]. Advocacy organizations have an important role to play in supporting people with disability and their families [53] and require adequate resourcing [41]. Consistency within NDIS processes and decision-making is vital to address current inequities, a sentiment shared by the recent NDIS review [36].

A second finding is that access to an individualized NDIS funding package was positioned as “high stakes,” which exacerbated the emotional toll experienced by prospective participants and other stakeholders. It is likely that this urgent need for the timely provision of funding and support was heightened because of the unique challenges associated with a young autistic person’s transition out of the structured familiar school environment. This is well documented as a difficult time in a young person’s life [2, 24]. There was an enduring perception among participants that without NDIS funding, the young people would not be able to access the support they need and that there would be no other adequate support. The perception of NDIS as a “one-stop shop” for disability supports funding is a widely held view [35, 37], which was built into the original design of the NDIS in the hopes of streamlining access to funded disability support, bringing them under one “umbrella”’ [29]. This finding clearly highlights the inadequacies of Tier 2 of the NDIS (information linkages and capacity building or “foundational supports”). Tier 2 was intended to ensure that mainstream community supports and informal supports were available to facilitate the integration of people with disability into the community [35], decreasing the reliance on individualized packages and support provided at Tier 3 [37], which were only ever intended for those with higher support needs [29]. These findings offer important evidence of the clear failing of Tier 2 (“foundational supports”) and highlight the critical need for accessible and visible support for all people with disability, not just those with individual funding packages [36]. If Tier 2 supports were more readily visible, accessible, and available to people with disability, the perception of access to Tier 3 supports may not have been positioned as high stakes with dire consequences for no access. Regardless of the intention to facilitate widespread availability of Tier 2 supports to facilitate mainstream inclusion, participants in the present study perceived that individualized funding packages were the only way to gain the disability support they needed. This perception of inadequate or invisible Tier 2 supports echoed in other studies [35, 37]. There are concerns that continued underfunding of Tier 2 supports under the NDIS will serve to exacerbate inequities and marginalization for people with disability who cannot access adequate supports, in addition to adding financial pressures to the provision of Tier 3 supports [35, 37]. It would appear that adequate provision of disability support at Tier 2 is not only a moral imperative but also an economic one. There may be an urgent need to enhance funding for Tier 2 disability supports, enhancing the capacity of the “mainstream” community to include people with disability.

This study also found that the time and financial toll experienced by participants to seek access was substantial. The administrative burden to acquire NDIS access has been reported in other studies, although those studies were not focused on autism or the transition to adulthood. Carey and Malbon [39] conducted a systematic review and found that studies overwhelmingly suggested that the administration involved in gaining access to the NDIS was burdensome and that this was compounded by the fact that people with disability had never experienced personalization of their support needs before [39]. The personalization of support, which was posited as providing choice and control to people with disabilities, has exacerbated the administrative burden [30, 39]. Choice and control are offered in theory with the implementation of the NDIS, but for many people with disabilities, it has not been realized in practice [30]. It may only be achieved if people with disability can actually navigate the systems [54], which has reportedly been a challenge [39, 43].

This emotional toll and inequity were further compounded by the navigation challenges identified between prospective NDIS participants and the NDIA, adeptly described as a maze. Inconsistency of information provided by the NDIS to participants has been highlighted by others [39]. Olney and Dickinson [30] reported that participants needed to know the “right jargon” in order to successfully interact with the scheme.

It is possible that this emotional toll is experienced differently by different participants and that prospective participants may present with different capacities with regard to coping [39], resources, and capacity [21]. This exacerbates inequity for some people who do not have the capacity or the support to keep going through the process. Some of the participants in the present study had given up or withdrawn from the process of applying. This disempowerment with the NDIS has been observed in other studies [21, 39].

In drawing meaning from the data, it is important to consider the implications of researcher positionality. The research team presents a mix of insider and outsider perspectives, with one of the three having a disability. This limited disability lived experience may have led to gaps in fully understanding the lived experiences of autistic people. The researchers’ extensive experience in the Australian disability sector and their work with the NDIS lends credibility and depth to their analysis; however, this may have led them to interpret data in a way that aligns with their past experiences.

4.1. Limitations

The present study represented a relatively small subset of people from various stakeholder groups within New South Wales, Australia, with participant perspectives highlighting significant challenges for some young people trying to access the NDIS during the important transition from school to tertiary study and work. One noted limitation was the number of quotes from young autistic people themselves regarding NDIS access. Most of this information came from parent carers, service providers, and educator participants. This may be representative of the role that parents and professionals have in advocating for NDIS access on behalf of young autistic people. A further limitation was that the young autistic people whose voices feature in this paper should not be considered representative of all autistic people and all NDIS access experiences. It should be noted that for many people, the NDIS is reportedly meeting their needs in terms of providing necessary disability support through the provision of individualized support packages [32, 55] and that the NDIS supports many autistic children and young people, who are reported to be the largest participant group within the NDIS [44]. Nevertheless, for the autistic young people described in the present study, many of whom had not been successful in gaining NDIS supports their views may be less prevalent but not less important.

5. Conclusion

This study is the first to represent multiple stakeholder views highlighting the difficulties experienced by a group of autistic young people and their supporters in accessing individualized funding supports to successfully transition to postschooling, an area of importance as identified by the recent NDIS review [36]. This study found that the processes required to access Tier 3 may exacerbate inequities whereby those experiencing disadvantages such as low socioeconomic status or low levels of capacity are less likely to successfully access the required Tier 3 supports. Furthermore, this study highlighted the inadequacy of funding and support at Tier 2 which resulted in Tier 3 being the only place to acquire support. This finding will contribute to meeting the broad aims of the NDIS with regard to building the capacity of mainstream services to facilitate people with disability living an ‘”ordinary life” within their communities and ensuring that those who need Tier 3 support the most are not locked out based on reduced capacity for their advocacy.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) on 23rd July, 2020 (Approval no: 13884). Research was conducted in line with the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (updated 2018) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

In addition, approval was gained from the State Education Research Approvals Procedure (SERAP) (Approval no: SERAP 2020291, Approved 21st August, 2020), allowing the conduct of research with students and staff within public schools in New South Wales, Australia.

All adult participants gave written and verbal informed consent for their participation in line with ethical approvals. Where a participant was under the age of 18, they gave their written and verbal assent to participate and their parent signed a consent form on their behalf.

Consent

Please see the Ethics Statement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Caroline Mills led the study overall and took part in design, ethical approval, data collection, data analysis, and led on interpretation for this manuscript and write up of results for publication. Caroline Mills also led some of the advisory committee meetings throughout the study.

Danielle Tracey advised on the design of the overall study from its inception as well as ethical approval, recruitment of participants, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and write up of results for publication. Danielle Tracey also led some of the advisory committee meetings throughout the study.

Nicole Sharp advised on the design of the overall study, as well as ethical approval, recruitment of participants, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and write up of results for publication. Nicole Sharp also led some of the advisory committee meetings throughout the study and offered a lived experience perspective to the work.

Funding

Funding was received from Northcott Disability Services (a not-for-profit disability service provider) to conduct this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank the participants for sharing their stories with us as well as the members of the external advisory committee. The authors also wish to acknowledge and thank the staff at Northcott Disability Services for their support of this work.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the qualitative nature of this work and the risk that a participant may be identifiable through their interview transcript. Details about the data which would not identify participants are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.