Barriers to Participation in Nature Prescriptions: Evidence From a Cross-Sectional Survey of Adults in Australia, India, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Abstract

Cities, states, and countries across the globe are recognizing the interconnections of human and planetary health, and are investing in greening. Nevertheless, environmental improvements may not bring adequate changes in exposure needed to reduce chronic disease and improve mental health. Nature prescription, in which a health provider refers a patient to spend time outdoors, is a potential behavioral intervention that could connect people to accessible green spaces. However, formidable patient barriers could reduce the potential to scale-up implementation in equitable and sustained ways. We surveyed 2625 adult respondents within Australia, India, Singapore, the United States, and the United States about their perceptions of a set of seven potential barriers to participation in nature prescriptions. Analyses revealed that respondents in India and Singapore, although most aware of and experienced with nature prescriptions, reported facing greater barriers than in other countries. Weather was the most commonly reported barrier, followed by the lack of time and distance. A lack of interest was a greater barrier among young, urban respondents with a college degree. The barrier of the lack of company was greater for urban residents and for those experiencing financial difficulty. In addition, contrary to many prior studies, we observed greater overall perceived barriers for respondents with higher education levels. Many of the perceived barriers covered by our survey are structurally modifiable, and programs developing in each of these locations may draw from these findings to tailor outreach strategies.

1. Introduction

The rising burden of chronic disease and increasingly sedentary, screen-based lifestyles is a significant cause of concern globally. Chronic diseases constitute the leading cause of global mortality, accounting for 41 million people annually, or 74% of all deaths worldwide [1]. They disproportionately affect people in low- and middle-income countries where more than three-quarters of global noncommunicable disease deaths (31.4 million) occur [2, 3].

There is increasing awareness that living environments contribute significantly to public health and the global burden of disease. Aside from risks posed by exposures to air, water and noise pollution, and inadequate housing and infrastructure, a near-universal pattern within human settlements has been the loss of natural resources such as green and blue spaces, or what many refer to simply as “nature” [4, 5].

1.1. Evidence Regarding the Benefits of Nature for Health

Ample evidence indicates that contact with green space provides a range of mental [6], physical [7], and social [8] health benefits by facilitating stress relief [6], restoring cognitive capacities [9, 10], promoting physical activity [11], improving sleep [12], reducing loneliness, and increasing social connections [8]. Globally, cities, states, and countries are investing in greening strategies and mass tree planting (e.g., Sydney [13], Birmingham [14], Uttar Pradesh [15], Seattle [16], and Singapore [17]). These investments will have potentially large impacts on population health through cooling heat islands [18] and regulating air quality [19].

However, relying solely on increasing green spaces without finding ways to increase access and exposure may not maximize their prevention potential. There are many barriers to increasing the use of existing natural resources. There is a rising population-wide sense of disconnectedness from “nature” [20]. Previous research also indicates that the lack of interest [21], time [22] and adequate transport [21, 23–25], affordability [22, 25, 26], lack of company [8], as well as caregiving responsibilities [27], and weather conditions [28] are common barriers to engaging with nature.

Sociodemographic characteristics may also influence access and perceived access or barriers to greenspace. Gender and age have been found to be the determinants of how green space is used and perceived [29]. For example, based on a survey of 2866 residents living close to greenspaces in an urban area of Sweden, Sang et al. [29] found that women accessed these spaces more than men. Another study based on an Irish population sample found that park visitation increases with age [30]. Greenspace access has also been shown to vary across urban to rural continuums. In addition, what natural spaces remain in populated areas are often distributed inequitably [31–33]. Lower-income individuals are less likely to spend time in nature than their peers even if there are green spaces nearby [34–37]. A salient question is how can societies generate supportive, equity-focused pathways that enable everyone to benefit from these green spaces?

1.2. Nature Prescriptions

Nature prescriptions (also called park prescriptions or green social prescriptions) could be part of the solution [38, 39]. Nature prescriptions are recommendations from health professionals, or other institutions such as schools, parks and recreation departments, or garden associations, for an individual to increase the amount of contact they have with natural surroundings for the purpose of health and well-being [40]. This might be in an unstructured (e.g., the patient visits an outdoor space on their own) or structured way (e.g., the patient joins a group-based social or physical activity taking place in a park) [41]. While there are many research gaps [41], current findings are promising; meta-analysis indicates that participation in nature prescriptions leads to increased daily step counts and reductions in blood pressure, anxiety, and depression [42].

Recent work finds high levels of interest in nature prescriptions even in individuals with low levels of nature contact and a variety of mental, physical, and social health needs [43]. Hundreds of nature prescriptions have already been issued in the United States [44], the U.K.’s National Health Service is currently investing £5.5 m in pilot programming and evaluation at seven test and learn sites [45], and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners are recommending “social prescriptions” be part of standard care [46]. However, currently, there is little evidence on who provides and uses these nature prescriptions, whether prescriptions are accessible, affordable, and acceptable to those with high potential to benefit, and how best to retain participants. There is a need to define evidence-based strategies for scaling up implementation in equitable and sustained ways.

In particular, an understanding of the potential barriers to engaging in a nature prescription is an important starting point and constitutes a clear focus for future intervention development [47]. Prior studies have measured changes in patient health outcomes associated with receiving a nature prescription or adhering to a nature prescription. However, tracked adherence rates are often low, and barriers to following through with a provider’s recommendation to spend time outdoors are not typically explored in the nature prescription literature [41]. While barriers to engaging in social prescribing faced by providers are equally important, the focus of our study was to explore these potential barriers from the perspective of someone who might receive a nature prescription, and how they vary within populations across five countries with contrasting economic, cultural, and climatic contexts. We explore sociodemographic patterns and predictors of multiple potential barriers to nature prescriptions using a survey of adult populations within Australia, India, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

The aim of this survey was to gain insight into the demand, participation, and preferences surrounding nature prescriptions. We distributed the survey to participant panels using the online survey platform Qualtrics XM (Salt Lake City, UT, U.S.A.). Qualtrics maintains an international database of potential panel survey participants. For the present study, we recruited English-fluent adults (over age 18) residing in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where the investigators who received cross-university funding from the University Global Partnership Network are located. Prior knowledge of or experience in nature prescription programs was not a requirement for inclusion. The study team also sought to include low- and middle-income countries with an adequate Qualtrics sample, where known nature prescription programs or research exists, and chose India and Singapore [48]. We first recruited a pilot sample of a minimum 50 participants per country, and analyzed the results and survey flow. Following minor changes in wording and answer requirements, the final sample was approximately 525 participants per country or a total sample of 2625.

Qualtrics XM recruits panel participants through a variety of methods including email invitations, an online portal, SMS notifications, and in-app notifications. Potential participants are informed that the survey is for research purposes only, the expected duration of the survey, and what incentives are available. Incentives were tailored within each country using prior experience among the study team of what motivates people to participate in surveys. Incentives included any of the following: cash, airline miles, gift cards, redeemable points, charitable donations, sweepstakes entrance, and vouchers. To limit self-selection bias, survey invitations do not include specific details regarding the current survey topic. The survey began by providing the following definition of nature prescription (or green social prescription): “programs where a trusted health or wellness professional recommends or prescribes time or activities in green, natural spaces such as parks, forests, or gardens for human health and wellness benefits.” The survey then proceeded with questions regarding participant perceptions and experiences with such programs (both structured and unstructured). The full questionnaire (provided in Appendix A) was designed to take less than 10 min to complete, in order to increase participation and completion [49]. Data collection occurred between September 6, 2022, and September 16, 2022, and the survey took an average of seven minutes and 35 s. Qualtrics XM panels have been shown to be demographically and politically representative in countries such as the United States and India [50]. For the study sample, there was an 18% incidence rate (percentage of people who initiated the survey, met inclusion criteria, and completed the survey).

2.2. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the ethics board at North Carolina State University (Approval No. 25171). All respondents provided consent to participate in the study.

2.3. Measures

- 1.

Lack of interest in natural and greenspaces

- 2.

Distance to nearby greenspaces, parks, forests, or gardens

- 3.

Transportation access to nearby greenspaces, parks, forests, or gardens

- 4.

Availability of time for adhering to nature prescriptions

- 5.

Caregiving demands (e.g., children or older family members that would require care during greenspace visits)

- 6.

Weather/climate

- 7.

No one to go with (“no company”)

2.4. Statistical Analysis Methods

For all analyses, we considered the following variable categories: age (aged 19–44, 45–65, and 66+), education (no college degree, college degree, or graduate degree), financial management (“comfortable,” “getting-by,” or “difficult”), and urban/rural status (urban, suburban, rural). For gender, we did not include categories (4) nonbinary or (5) no answer due to low frequency in these responses (n = 12). We considered barrier categories: extremely unlikely or somewhat unlikely; neither likely nor unlikely; or somewhat likely or extremely likely. In addition, we calculated a cumulative barrier index, as the sum of all barriers responses (using the original coding).

We first calculated the descriptive statistics of the sociodemographic variables, each specific barrier and the barrier index, including distributions and proportions for the overall sample, and by country. Next, we ran multiple linear regression models with the barrier index as the dependent variable for the full sample. Each model adjusted for age, gender, urban/rural status, education, financial management, and country. We then ran multiple linear regression models with barrier measures as the dependent variables for the full sample. Model adjustments were the same as in models of the barrier index. In these models, we excluded demographic categories that consisted of 10% of respondents or less (ages 66+ in all countries).

Finally, we ran a bivariate linear model to test whether the barrier index was associated with awareness of nature prescription programs and therefore whether awareness may have influenced barrier reporting. Awareness categories were “not aware”; “aware but unsure of exact definition”; “aware and able to define”; or “participant.” We conducted all analyses in Stata v15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

3. Results

There were a total of 2625 survey responses, well-balanced between countries (ranging from 523 in Singapore to 526 in India and the United States; see Supporting Table B1). There were missing answers for the education variable (n = 36) comprising less than 1% of survey responses. There were no missing responses to the barriers questions.

Reponses, by country, to the question, “Prior to this survey, please select your awareness of green social prescriptions (also referred to as nature or park prescriptions, or forest bathing)” are shown in Table 1. There was high awareness of nature prescription programs in Singapore, India, and the United Kingdom, and the highest proportion of respondents reporting they had participated in such a program (14%) was in India.

| Not aware | Aware of the idea but not sure what it is | Aware of the idea, could define | I am a participant in such a program | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 269 (51.2%) | 176 (33.5%) | 50 (9.5%) | 30 (5.7%) |

| Singapore | 123 (23.5%) | 214 (40.9%) | 147 (28.1%) | 39 (7.4%) |

| India | 60 (11.4%) | 179 (34.0%) | 210 (39.9%) | 77 (14.6%) |

| United Kingdom | 159 (30.2%) | 204 (38.8%) | 145 (27.6%) | 17 (3.2%) |

| United States | 253 (48.1%) | 165 (31.3%) | 73 (13.8%) | 35 (6.6%) |

The sample was 58% female, and a large proportion of respondents were between ages 19–44 (77%), were living in an urban (45%) or suburban setting (41%), held a college degree (67%), and were comfortable (50%) or getting-by (31%) financially (see Table B1). Notable variations are that a larger proportion of respondents were aged 66+ (14%) in the United States than in other countries, 74% of respondents were female in Australia, and 26% lived in rural areas in the United States. Only 7% of respondents in Singapore lived in rural areas. In India, while 90% of respondents reported holding a college degree, only 11% reported financial difficulty and 66% reported financial comfort.

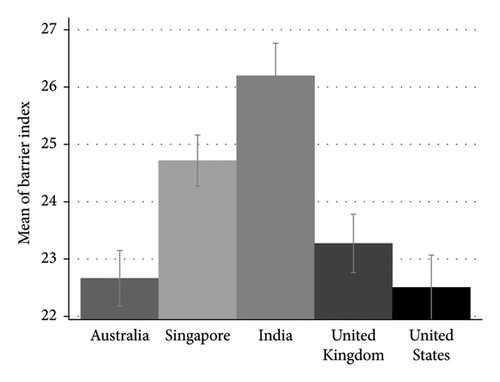

The mean and 95% confidence intervals of barrier index values by country are shown in Figure 1. Respondents in India reported the most barriers, followed by Singapore, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States.

Table 2 shows adjusted associations between the barrier index and sociodemographic variables. Middle age (ages 45–65) was associated with lower barrier index values (relative to younger age); however, this association is mostly driven by the difference found in the United States. There were no differences between gender groups. Suburban and rural locations were associated with lower barriers (especially in the United Kingdom and the United States). The lack of college degree was associated with lower barriers except in the United States. And there was no overall association between financial management status and the barrier index, but getting-by financially in India was associated with lower barriers than financial comfort.

| All countries | AUS | Singapore | India | United Kingdom | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (reference: aged 19–44) | ||||||

| Aged 45–65 | −0.94 ∗∗ | −1.27 | −0.32 | −1.12 | −0.52 | −1.49 ∗∗∗ |

| (0.31) | (−0.73) | (−0.58) | (−1.08) | (−0.66) | (−0.67) | |

| Aged 66+ | −2.94 ∗ | |||||

| (−0.87) | ||||||

| Gender (reference: male) | ||||||

| Female | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| (0.24) | (−0.57) | (−0.46) | (−0.58) | (−0.53) | (−0.61) | |

| Urban/rural (reference: urban) | ||||||

| Suburban | −1.05 ∗∗∗ | −0.89 | −0.03 | −1.16 | −1.88 ∗ | −1.32 ∗∗∗ |

| (0.27) | (−0.59) | (−0.51) | (−0.79) | (−0.57) | (−0.67) | |

| Rural | −1.22 ∗∗ | −1.40 | −0.92 | −2.81 ∗ | −1.40 | |

| (0.37) | (−0.89) | (−0.88) | (−0.81) | (−0.77) | ||

| Education (reference: college degree+) | ||||||

| No college degree | −1.03 ∗∗∗ | −1.48 ∗∗ | −1.49 ∗∗ | −2.33 ∗∗∗ | −1.48 ∗∗∗ | 0.47 |

| (0.27) | (−0.51) | (−0.53) | (−0.98) | (−0.58) | (−0.59) | |

| Financial management (reference: comfortable) | ||||||

| Getting-by | −0.49 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −3.53 ∗ | −0.14 | 0.46 |

| (0.27) | (−0.57) | (−0.51) | (−0.69) | (−0.60) | (−0.67) | |

| Difficult | 0.36 | 0.20 | 1.36 | 0.74 | 0.27 | 0.11 |

| (0.32) | (−0.65) | (−0.71) | (−0.91) | (−0.66) | (−0.75) | |

| Country (reference: Australia) | ||||||

| 2.70 ∗∗∗ | 1.61 ∗∗∗ | 0.42 | 0.35 | |||

| (0.41) | (0.39) | (0.37) | (0.38) | |||

- 1AUS: Australia; U.K.: United Kingdom; U.S.: United States of America.

- 2Coefficients (and standard errors) from multiple linear regression adjusted for all variables listed in the table.

- 3 ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

When considering specific reported barriers to nature prescription participation, weather (65%) was the most commonly reported, followed by time (58%) and distance (56%) (Table 3). This pattern held in most countries, except that distance was more of a barrier than time in the United States, and the lack of company was the third largest barrier reported in Australia (compared to the fifth largest barrier in all other countries). Reported barriers were most frequent in India and secondly in Singapore (except the lack of interest and no company).

| Barriers | All countries | AUS | Singapore | India | United Kingdom | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather | 65% (1) | 60% (1) | 68% (1) | 75% (1) | 59% (1) | 60% (1) |

| Time | 58% (2) | 53% (2) | 62% (2) | 69% (2) | 57% (2) | 48% (3) |

| Distance | 56% (3) | 46% (4) | 61% (3) | 67% (3) | 53% (3) | 52% (2) |

| Transport | 54% (4) | 44% (6) | 61% (4) | 66% (4) | 51% (4) | 47% (4) |

| Caregiving | 51% (5) | 45% (5) | 53% (5) | 65% (5) | 48% (5) | 42% (5) |

| No company | 48% (6) | 47% (3) | 47% (6) | 57% (6) | 46% (6) | 41% (6) |

| Lack of interest | 42% (7) | 32% (7) | 44% (7) | 56% (7) | 38% (7) | 36% (7) |

- 1AUS: Australia; U.K.: United Kingdom; U.S.: United States of America.

The proportion of respondents reporting somewhat/very likely barriers, by the sociodemographic category, are shown in Supporting Figure B1. Within-variable difference in estimates (compared to reference categories) from fully adjusted regression analyses is indicated. Table 4 shows the regression estimates of specific barriers from fully adjusted regression models (including all sociodemographic variables) of the total sample.

| Covariate | Lack of interest | Distance | Transport | Time | Caregiving | Weather | No company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (reference: aged 19–44) | |||||||

| Aged 45–65 | −0.12 ∗ | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.11 ∗∗ | −0.03 | −0.09 ∗ |

| (−0.05) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | |

| Gender (reference: male) | |||||||

| Female | −0.01 | 0.07 ∗ | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 ∗ | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.03) | (−0.03) | (−0.03) | (−0.03) | (−0.03) | |

| Urban/rural (reference: urban) | |||||||

| Suburban | −0.08 ∗ | −0.15 ∗∗∗ | −0.11 ∗∗ | −0.07 ∗ | −0.09 ∗ | −0.06 | −0.11 ∗∗ |

| (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.04) | |

| Rural | −0.09 | −0.16 ∗∗ | −0.18 ∗∗∗ | −0.14 ∗∗ | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| (−0.05) | (−0.05) | (−0.05) | (−0.05) | (−0.05) | (−0.05) | (−0.05) | |

| Education (reference: college degree+) | |||||||

| No college degree | −0.16 ∗∗∗ | −0.12 ∗∗ | −0.07 | −0.12 ∗∗∗ | −0.11 ∗∗ | −0.10 ∗∗ | −0.01 |

| (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.04) | |

| Financial management (reference: comfortable) | |||||||

| Getting-by | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.08 ∗ | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.04) | (−0.03) | (−0.04) | |

| Difficult | −0.01 | 0.10 ∗ | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13 ∗∗ |

| (−0.05) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | (−0.04) | |

- 1AUS: Australia; U.K.: United Kingdom; U.S.: United States of America.

- 2Coefficients (and standard errors) from multiple linear regression adjusted for all variables listed in the table.

- 3 ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p < 0.05.

- 4Barrier values: 1 = extremely unlikely; 2 = somewhat unlikely; 3 = neither likely nor unlikely; 4 = somewhat likely; 5 = extremely likely.

Older age was associated with lower barriers related to the lack of interest, caregiving, and lack of company. Overall, female respondents reported significantly greater barriers associated with distance and caregiving. Suburban location was associated with lower barriers than urban location, except for weather. Rural location was associated with lower barriers of distance, time, and transport than the urban location. The lack of college degree was associated with lower barriers, except for barriers associated with transport and lack of company. Reported financial difficulty was positively associated with barriers relating to the distance and lack of company, indicating that those getting-by or facing financial difficulty faced greater barriers than those reporting financial comfort.

Finally, we found a statistically significant association between nature prescription awareness and reported barriers. Compared to participants with no awareness, respondents with some awareness reported higher barriers (ß = 1.17, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.61, 1.70), respondents with good awareness reported higher barriers (ß = 3.20, 95% CI: 2.63, 3.84), and respondents who had participated in programs reported even higher barriers (ß = 6.59, 95% CI: 5.68, 7.50).

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Reported Barriers

Identifying and instituting measures to address barriers to participation in nature prescriptions is critical to minimize risks of poor uptake and adherence commonly seen in other behavioral interventions [38]. While a previous review surveyed findings largely from studies of social prescription programs in the United Kingdom [47], this is the first study to assess the challenges facing nature prescription programs for a variety of demographic groups from a multicountry perspective. It is notable that while there is little documentation of nature prescription programs in India and Singapore, we found a higher percentage of survey participants reported being aware and able to define a nature prescription program in India and Singapore, compared to Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. A higher percentage of participants reported having participated in such a program in India and Singapore, as well. It could be that these practices are common in these countries but are not necessarily described with the same terms.

At the same time, our key findings indicate greater barriers to nature prescriptions in India and Singapore, compared with Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with inclement weather being the most common. Across all countries, time scarcity and prohibitive travel demands were also frequently cited, with a lack of intrinsic interest being a factor among young urban respondents with a college degree in particular. A lack of company was also a barrier for urban participants, and those with more education tended to report more barriers.

Respondents in India, followed by Singapore, reported perceived barriers more frequently than in Australia, the United Kingdom, or the United States. This finding is influenced in part by the relatively greater barriers reported by rural respondents in India and Singapore compared to in Australia, United Kingdom, and the United States, which could be due to a number of factors. Previous research has shown that rural populations and women in India tend to consistently undertake lower levels of physical activity [50–52]. Prior research has highlighted that rural residents may engage more in domestic and occupational physical activity but often lack access to formal resources such as gyms, community centers, and other facilities that support structured physical activity [51, 52]. They may also face limited healthcare access, poor awareness of nature prescriptions, and a lack of resources and time to dedicate to physical activity [53]. Additionally, rural areas may lack infrastructure for active transportation, while in urban areas, crowding can discourage outdoor physical activity [54].

4.2. Reported Barriers by Category

4.2.1. Weather, Time, Distance, and Transport

Across all countries, weather (65%) was the most commonly reported barrier to nature prescriptions. While we could interpret that truly inhospitable weather deterred following through with a nature prescription and going outdoors, perception and expectations are likely at play [55]. Time (58%) and distance (56%) were the next most commonly reported barriers. Green spaces are often distributed unevenly, which impacts access [23, 56]. Indeed, affordability and availability of transport are common barrier to engaging in nature prescriptions in the United Kingdom [21, 24]. In addition, distance was the third highest reported barrier in Singapore. However, this finding underscores the influence of local perceptions on reported barriers; it is possible to travel across the island country in 1 hour. In very high-density urban settings like Singapore, perceived effort to get out of urban settings to surrounding open space may seem formidable [57].

4.2.2. Lack of Interest and Company, and Urban/Rural Status

Across all countries, the lack of interest was a greater barrier among the youngest respondents, compared to older respondents. It was also a greater barrier for urban residents and those with college educations. Perhaps younger respondents and those with college degrees show a greater lack of interest in nature prescription programs due to competing interests or that they feel they are otherwise healthy enough and do not need an intervention.

Urban respondents reported greater barriers to nature prescriptions than suburban and rural respondents across all countries. A lack of company was a greater barrier for urban residents and for those experiencing financial difficulty. This may reflect generally higher levels of single-person households in cities and family-oriented homes in the suburbs; however, this result may also reflect high levels of loneliness in society [58, 59], which commonly occurs even among people who are in relationships or surrounded by others [60]. A lack of company may deter people from the outdoors because they rather enjoy shared rituals and collective experiences, or feel greater perceived safety when with company in unfamiliar surroundings [8]. This was the third largest barrier reported in Australia (compared to the fifth in all other countries). This points to the potential importance of social motivations to improve participation in nature prescriptions, as well as the potential of such programs to reduce loneliness among those who are economically vulnerable [8].

4.2.3. Reported Socioeconomic Status

While previous research has identified barriers facing individuals with lower income and educational attainment, our research observed few patterns by perceived financial well-being, except in India where respondents in the perceived middle-income category reported significantly lower barriers than the other categories. This result remains uncertain; however, as our sample in India was especially skewed toward those with higher education, which may have excluded many for whom economic precarity is the norm. Further research with a nationally representative sample will help to affirm this result.

In addition, across all countries, we observed greater overall perceived barriers for respondents with higher education levels. In general, respondents with a college degree reported greater barriers associated with nature prescriptions but especially in Australia, Singapore, India, and the United Kingdom. While well-resourced respondents reported barriers to nature prescriptions more frequently, this does not necessarily reflect behaviors. It could be that while lower-income groups face greater barriers to getting outdoors, these barriers are secondary to challenges they face in other life areas. Qualitative, exploratory work would be valuable to establish the actual reasons for this disconnect.

Finally, we found that reporting of barriers was significantly higher with increased levels of awareness of nature prescriptions. Respondents with personal experience in nature prescription programs reported the highest level of barriers.

4.3. Modifiable Barriers and Potential Solutions

The perceived barrier categories included in this survey can be lessened with various programs or policy approaches. In Table 5, we list potential solutions to each of the barriers. The solutions are not intended to be exhaustive and may be more or less feasible to implement for various stakeholders wanting to engage patients in nature-based activities. As with most nature prescription programs, implementing some of these recommendations may take diverse partnerships, leveraging, and outside financial support.

| Barrier/intervention |

|---|

| Weather |

| • Public education campaigns about things to do outside despite (e.g., rainy or cold) weather |

| • Provide appropriate outdoor gear at prescribed nature activities |

| • Suggest alternate locations or alternate dates for severe weather |

| • Provide structured activities of shorter duration during wet/cold/extreme heat |

| Lack of time |

| • Tailor programs that make use of nearby nature and that are not time-intensive. For example, 20-min lunchtime walks near locations of employment or high-density residential locations |

| • Schedule programs at various times to enable those who are working age, parents with babies, and the retired and unemployed are all able to attend |

| • Develop employer programs that encourage and incentivize nature activities during work hours |

| • Offer shorter timed programs a few times a day instead of time-intensive longer periods |

| Distance |

| • Increase public parks and green/blue spaces near centers of population |

| • Develop recreational facilities (e.g., trails or picnic areas) in existing open spaces |

| • Maximize the potential of existing local green space—as settings for nature-based health activities |

| • Map the green activity providers in an area to identify opportunities for nearby nature prescriptions |

| Transport |

| • Provide transport (e.g., a van, public transit passes, and Uber rides) to prescribed activities or park areas |

| • Subside transport for those with nature prescriptions |

| • Create transport plan with user on available travel options hold nature prescription activities at public parks that are easy to access by public transport or other modes of travel |

| • Organize people to travel together as a group (e.g., taking the same train together, walking bus, or led a group bike ride to the green space) |

| Caregiving |

| • Offer programs that tailor to parents/caregivers and their children/those in their care |

| • Programs could be offered at various times of day and days of the week |

| • Offer shorter timed programs a few times a day instead of time-intensive longer periods |

| Lack of company |

| • Coworkers who live close-by could be encouraged to get together in nearby parks, e.g., to “walk and talk” |

| • Encourage local organizations and community facilities (e.g., YMCA, YWCA) to develop social support programs (e.g., walking groups and setting up an exercise buddy system) |

| • Harness the potential of providers of group activities that take place outdoors (e.g., paths for all health walks and ramblers well-being walks in the United Kingdom) |

| Lack of interest |

| • Promote programs on social media and in advertising |

| • Partner with relevant institutions to engage people/patients from a young age to increase their nature relatedness and interest throughout life |

First, weather as a barrier probably reflects a blend of commonly inclement conditions and perceptions over what is and is not tolerable, rather than year-round inhospitable climatic conditions. Whether it is periods of intense heat, cold, or rain, park planners can play a vital role in ensuring that there are well-signposted and easily accessible pergolas under which people can feel safe to take temporary shelter. An effort to change cultural associations with weather might be warranted, for example, that we tend not to go out in the rain, although a campaign to raise public awareness of precautionary measures (e.g., appropriate clothing) to increase resilience and enjoyment of the outdoors during less-than-ideal weather conditions might be valuable to consider.

Distance frequently corresponded with lack of time and caregiving barriers and likely reflects the complex and almost universally gendered intersection of work–life demands. While time in nature is often assumed to be an activity for weekends and free time, this does not necessarily need to be the norm. Research has shown the benefits of green workplaces and employer programs to incentivize employee breaks in natural settings [61]. In a post-COVID-19 pandemic time when more people are working from home, employer programs could organize and encourage coworkers who live nearby to walk and talk in natural settings, which can support both team building and health [62]. Even short amounts of time, for example, momentary views or short periods of being outdoors might have positive short-term effects, for example, on attention [63].

The perceived barrier of distance is one that can be structurally remedied by developing public parks and greenspaces closer to centers of population, or identifying existing local green spaces as settings for health activities [21]. Mapping of the available green activity providers may also help to identify opportunities for nature prescription in close proximity to where people live [21]. For rural populations, this might mean installing recreation facilities such as trails or picnic spots in existing open spaces. For specialist health services that recognize and seek to enable individuals with more time in nature than they would normally have, such as mental health professionals treating people living with depression, the provision of dedicated transport is understood to be crucial as patients can regard the use of public transport (even if available) as a barrier to participation [64, 65].

Companionship is an important component to getting outdoors. The company of others has been found to increase enjoyment and motivation for regular participation in outdoor activities [66, 67]. While the lack of company might be a barrier to spending time outside, being outside with others has been shown to effectively reduce loneliness and social isolation [66]. Nature prescription programs could act as “Meetups” with a designated group of similar others or may bring people together for purposes of enjoying the outdoors as a shared experience without necessarily requiring any direct interaction with other humans [8].

Program promotion via social media and other relevant news or press outlets may help peak interest in outdoor programs. In addition, given that we know that early life exposure to outdoor experiences can increase environmental attitudes and behaviors [68], although the scope of this kind of solution may be beyond any one group (especially smaller ones), it may be important to engage people/patients from a young age.

Addressing perceived barriers associated with caregiving can be met in a number of ways. First, outdoor programs and activities could be tailored to parents or caregivers and their children, such as Bumps and Buggies Parent and Baby outdoor walking groups. For caregivers who are hoping to join a nature activity without their child, offering more frequent activities of shorter duration could help accommodate individuals with limited time and range.

Finally, getting outdoors is often a socially driven process. People go outdoors with friends and family, and a culture of getting outdoors is shared within families, social networks, and communities. Lack of interest, therefore, is something that could be addressed with strategic marketing coming from leaders or influencers within these groups.

4.4. Study Limitations

This study is subject to a number of limitations. Survey questions reflect self-reported perceptions of barriers to nature prescriptions, and while perceptions are potentially highly influential to behaviors, they do not necessarily align with actual behaviors. Due to the lack of resources, the samples are not representative of country populations and sample size for each of the countries is not adequate for generalizability. Rather, the focus was to gain a breadth of understanding of regard to green social prescriptions in a variety of countries for which these programs are relevant but underexplored. Another potential limitation is that the survey sample did not necessarily have prior knowledge of or experience participating in a nature prescription program. However, our intent was to obtain perceptions of nature prescriptions not only from former/current participants, to gain a sense of potential barriers to follow-through for patients first receiving a prescription. Nevertheless, answers could depend on awareness of and experiences with nature prescriptions, outdoor activities, nature relatedness, cultural values, and local context. Indeed, the study found that personal experience in nature prescription programs increased perceptions of barriers. Since a small percentage of our respondents had personal experience in nature prescription programs, their reported barriers may have been muted and our findings may have been biased toward the null. There could also be sociodemographic influences on or patterns in reported barriers unmeasured in our survey and specific to each of the five countries.

In addition, the study team also designed a survey that would be manageable for participants to complete and therefore potentially salient barriers (e.g., disbelief in the benefits of nature) may have been omitted from the survey. Because the study team did not include an open-ended response option, we were not able to collect potential barriers outside of the provided options.

In addition, our survey questions regarding barriers to follow-through on a nature prescription were not specific to formal versus informal prescription. Because nature prescriptions are not universally provided by medical providers, we also did not ask about barriers associated with trust in the healthcare system, or, for example, stigma associated with seeking treatment for mental health concerns. Further research examining barriers specific to nature prescriptions from healthcare providers, and specific to either formal or informal prescriptions, is warranted.

5. Conclusions

An understanding of the potential barriers to engaging in a nature prescription is an important starting point and constitutes a clear focus for future intervention development. Our survey of populations within five countries identified sociodemographic patterns and associations with seven potential barriers to participation in nature prescriptions, across and between five countries including three in the global south. Programs developing in each of these locations may draw from these findings to tailor outreach strategies that target sociodemographic groups reporting relatively greater perceived barriers. In addition, many of the perceived barriers covered by our survey are structurally modifiable (they could be reduced with policy initiatives or programs), and cooperation among healthcare agencies, governments, parks managers, and employers, to name a few, could address many of them. A next step will be to test the effectiveness of interventions to address these barriers.

Disclosure

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. This work was conducted and completed in 2023-24.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Universities Global Partnership Network (UGPN).

Endnotes

1Statistically significant (p < 0.05) difference between the category and the reference category (reference categories are ages 19–44, male, urban, college degree+, and financially comfortable).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Appendix A: Survey Questions

- A.

Informed Consent

- •

There are an increasing number of organizations that provide activities in natural, green, or blue environments, which people can access for their health. The target audiences, aims, activities, and locations of these nature-based activities vary greatly. The aim of this survey is to gain insight into the demand, participation, and preferences surrounding Green Social Prescriptions (GSPs).

- •

You are being asked to complete a survey for research purposes. This survey is part of an international research project looking into the different types of nature-based activities, programs, or interventions that are delivered in the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, India, and Singapore. This project is managed by researchers at North Carolina State University (United States), the University of Wollongong (Australia), and the University of Surrey (United Kingdom). The results of the survey will inform this international research project, and the green social prescription work is done across the globe.

- •

Completing this survey is voluntary, and you can stop at any time by closing the web browser.

- •

You must be 18 years of age or older, reside in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Singapore, or India to participate in this study.

- •

There are minimal risks associated with your participation in this survey. You will receive an incentive from Qualtrics for completing this survey. In order to receive full compensation for completing the survey, you must complete all items to the best of your ability.

- •

If you have any questions about the survey, how it is implemented, or the research study, please contact the lead researcher at NC State University, J. Aaron Hipp, at [email protected] and 919.515.3433. Please reference study number 25171 when contacting anyone about this project.

- •

If you have questions about your rights as a participant or are concerned with your treatment throughout the research process, please contact the NC State University IRB Director at IRB-[email protected], 919-515-8754, or fill out a confidential form online at https://research.ncsu.edu/administration/participant-concern-and-complaint-form/

- •

If you consent to complete this survey, please click “Yes I consent” button to see the survey.

- •

- B.

Awareness of Green Social Prescription (GSP) Programs

- 1.

Prior to this survey, please select your awareness of green social prescriptions (also referred to as nature or park prescriptions, or forest bathing):

- i.

Not aware

- ii.

Aware of idea, but unsure of what it is

- iii.

Aware of idea, could define

- iv.

I am a participant in such a program

- i.

- 1.

- C.

Definition of Green Social Prescriptions

- a.

Green Social Prescriptions are programs where a trusted health or wellness professional recommends or prescribes time or activities in green, natural spaces such as parks, forests, or gardens for human health and wellness benefits.

- b.

Provided the above definition, are you aware of any such programs?

- i.

Yes, aware-open ended name

- ii.

Yes, I am a participant-open ended name

- iii.

No

- i.

- a.

- D.

[If yes to Cbi or Cbii] Previous Participation and Preference

- 1.

Which best describes the program(s) you participated in? (select all that apply)

- a.

The prescription or recommendation for a green social prescriptions was provided by:

- i.

Medical practitioner (e.g., physician, general practitioner, doctor)

- ii.

Medical clinician (e.g., nurse)

- iii.

Social worker or community health guide

- iv.

Parks and recreation professional

- v.

Program was self-guided

- vi.

Other___

- i.

- b.

The greenspace was (select all that apply):

- i.

Community garden or allotment

- ii.

Farm

- iii.

Park

- iv.

Botanic garden

- v.

Arboretum

- vi.

Common land

- vii.

Forest/woodland

- viii.

Meadow

- ix.

Green roof

- x.

Playing field

- xi.

Greenway/green corridor such as paths alongside a river or canal

- xii.

Wetland

- xiii.

Coast/sea

- xiv.

Cemetery

- xv.

City/urban environment

- xvi.

Indoors

- xvii.

Other (please write-in)

- i.

- c.

The prescription was:

- i.

Specific (e.g., visit a greenspace 10 min per day, 3 days per week)

- ii.

General (e.g., increase exercise by visiting a park more often)

- iii.

Counseling/education/awareness

- iv.

Self-guided (increase visits to greenspaces for health benefits)

- v.

Program-based (e.g., group walk along park trail, or outdoor yoga class)

- vi.

There was no prescription

- i.

- d.

The program or prescription was delivered by (select all that apply):

- i.

Trained volunteer

- ii.

Untrained volunteer

- iii.

Parks and recreation professional

- iv.

Personal trainer or qualified fitness expert

- v.

Community health worker

- vi.

Medical professional

- vii.

Social worker

- viii.

Program was self-guided

- ix.

Other___

- i.

- e.

Prescription was related to the following wellness behaviors and outcomes (select all that apply):

- i.

Physical health or physical well-being in general

- ii.

Weight loss or maintenance

- iii.

Increased exercise or physical activity

- iv.

Mental health or mental well-being

- v.

Emotional well-being (e.g., happiness)

- vi.

Reduced stress

- vii.

Improved attention, concentration or ability to focus

- viii.

Social well-being (e.g., social cohesion, social inclusion, social functioning)

- ix.

Motivation

- x.

Resilience

- xi.

Self-esteem

- xii.

Improved sleep

- xiii.

Improved nutrition

- xiv.

Developmental outcomes

- xv.

Increase time spent outdoors (duration)

- xvi.

Increased visits to outdoors (frequency)

- xvii.

Connection to nature

- xviii.

Sustainable or pro-environmental behavior

- xix.

Other (please write-in)

- i.

- f.

Age group for the prescription:

- i.

12 years old and younger

- ii.

13–19

- iii.

20–44

- iv.

45–65

- v.

66 years and older

- i.

- g.

Prescription was carried out:

- i.

Alone

- ii.

With family or friends

- iii.

With a class or program (with others, including nonfamily/friends)

- i.

- h.

Was your adherence or follow-through in the prescription:

- i.

Measured

- ii.

Not measured

- iii.

Unsure/uncertain

- i.

- a.

- 2.

[If no to Cbiii] Previous participation and preference:

- 3.

Please rank order the following Green Social Prescription traits, with one signifying the type of prescription you would most likely participate in:

- a.

Health and Wellness professional that is:

- i.

Parks and recreation professional

- ii.

Personal trainer or qualified fitness expert

- iii.

Community health or social worker

- iv.

Medical professional

- v.

Program that is self-guided

- i.

- b.

Greenspace that is (top 5):

- i.

Garden (community or botanic)

- ii.

Park

- iii.

Forest/woodland

- iv.

Greenway/green corridor paths

- v.

Blue spaces such as wetlands, river/canal, or coast/sea

- i.

- c.

Prescription that is:

- i.

Specific (e.g., visit a greenspace 10 min per day, 3 days per week)

- ii.

General (e.g., increase exercise by visiting a park more often)

- iii.

Counseling/education/awareness

- iv.

Self-guided (increase visits to greenspaces for health benefits)

- v.

Program-based (e.g., group walk along park trail or outdoor yoga class)

- i.

- d.

Prescription related to the following wellness behaviors and outcomes (top 5):

- i.

Physical health or physical well-being in general

- ii.

Increased exercise or physical activity

- iii.

Mental health or mental well-being

- iv.

Emotional well-being (e.g., happiness)

- v.

Social well-being (e.g., social cohesion, social inclusion, social functioning)

- i.

- e.

Prescription to be carried out:

- i.

Alone

- ii.

With family or friends

- iii.

With a class or program (with others, including nonfamily/friends)

- i.

- f.

Adherence to the prescription should be:

- i.

Measured/tracked

- ii.

Not measured/tracked

- i.

- g.

I believe Green Social Prescriptions would be most relevant for:

- i.

12 years old and younger

- ii.

13–19

- iii.

20–44

- iv.

45–65

- v.

66 years and older

- i.

- a.

- 1.

- E.

Levels of Demand

- a.

If you were provided with a Green Social Prescription for your physical well-being by your primary care physician, how likely are you to participate?

- i.

Extremely unlikely

- ii.

Somewhat unlikely

- iii.

Neither unlikely, nor likely

- iv.

Somewhat likely

- v.

Extremely likely

- i.

- b.

If provided a Green Social Prescription for your psychological well-being by your primary care physician, how likely are you to participate?

- i.

Extremely unlikely

- ii.

Somewhat unlikely

- iii.

Neither unlikely, nor likely

- iv.

Somewhat likely

- v.

Extremely likely

- i.

- c.

If provided a Green Social Prescription for your social well-being by your primary care physician, how likely are you to participate?

- i.

Extremely unlikely

- ii.

Somewhat unlikely

- iii.

Neither unlikely, nor likely

- iv.

Somewhat likely

- v.

Extremely likely

- i.

- d.

If provided a Green Social Prescription for your nutrition by your primary care physician, how likely are you to participate?

- i.

Extremely unlikely

- ii.

Somewhat unlikely

- iii.

Neither unlikely, nor likely

- iv.

Somewhat likely

- v.

Extremely likely

- i.

- a.

- F.

Affordability–willingness to pay

- a.

How much would you be willing to pay to participate in a green social prescription?

- i.

How much would you be willing to pay per visit for a green social prescription that includes access to parks, forests, or gardens that may feature an admission or use fee?

- ii.

Slide bar $0–$20

- iii.

Should be free/covered by health insurance

- i.

- b.

How much would you be willing to pay per visit for a green social prescription that includes access to a program (e.g., yoga class, walking group)?

- i.

Slide bar $0–$20

- ii.

Should be free/covered by health insurance

- i.

- c.

What is your willingness to pay per visit for a green social prescription that includes access to a garden (i.e., community garden and shareable tools)?

- i.

Slide bar $0–$20

- ii.

Should be free/covered by health insurance

- i.

- d.

I have participated in a green social prescription and I paid:

- i.

Not Applicable

- ii.

Slide bar $0–$20

- iii.

Over $20

- iv.

Unsure

- v.

Covered by insurance

- i.

- a.

- G.

How likely are the following to be barriers to your participation in green social prescriptions?

- a.

Lack of interest in natural and greenspaces

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- b.

Distance to nearby greenspaces, parks, forests, or gardens

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- c.

Transportation access to nearby greenspaces, parks, forests, or gardens

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- d.

Availability of time for adhering to green social prescriptions

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- e.

Caregiving demands (e.g., children or older family members that would require care during greenspace visits)

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- f.

Weather/climate

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- g.

No one to go with

- i.

1–5 Scale from Not a Barrier to Definite Barrier

- i.

- a.

- H.

Previous Experience with greenspaces (e.g., parks, trails)

- a.

How often do you visit the park or greenspace closest to your home:

- i.

Rarely

- ii.

Once per month

- iii.

Few times per month

- iv.

Once per week

- v.

Few times per week

- vi.

Everyday

- i.

- a.

- I.

Nature Relatedness Scale

-

For each of the following, please rate the extent to which you agree with each statement. Please respond as you really feel, rather than how you think “most people” feel.

-

[RANDOMIZE STATEMENTS]

- a.

My ideal vacation spot would be a remote, wilderness area

- b.

I always think about how my actions affect the environment

- c.

My connection to nature and the environment is a part of my spirituality

- d.

I take notice of wildlife wherever I am

- e.

My relationship to nature is an important part of who I am

- f.

I feel very connected to all living things and the earth

- 1.

Strongly disagree

- 2.

Disagree

- 3.

Neither agree nor disagree

- 4.

Agree

- 5.

Strongly agree

- 1.

- a.

-

- J.

Loneliness Scales

-

Please indicate for each of the statements the extent to which they apply to your situation, the way you feel now.

-

[RANDOMIZE STATEMENTS]

- a.

I experience a general sense of emptiness

- b.

I miss having people around

- c.

Often, I feel rejected

- d.

There are plenty of people that I can lean on in case of trouble

- e.

There are many people that I can count on completely

- f.

There are enough people that I feel close to

- 1.

Yes

- 2.

More or less

- 3.

No

- 1.

- a.

-

- K.

Time in nature

-

Approximately how many hours did you spend in green spaces and/or blue spaces in total over the last 7 days?

- 1.

< NUMBER RANGE 0–100, WHOLE NUMBER >

-

- L.

Financial precarity

-

How well would you say you yourself are managing financially these days? Would you say you are…?

- 1.

Living comfortably

- 2.

Doing alright

- 3.

Just about getting-by

- 4.

Finding it quite difficult

- 5.

Finding it very difficult

- 1.

-

- M.

General health questions

- a.

Please indicate for each of the five statements which is closest to how you have been feeling over the last 2 weeks. Notice that higher numbers mean better well-being.

- b.

- c.

(ABOVE FROM WHO)

- d.

IPAQ Short -

- i.

- ii.

(Seven questions)

- iii.

- a.

- N.

Demographics

- a.

Qualtrics will give us most of these since a panel. What would we want to be certain is included:

- i.

Gender

- ii.

Race/ethnicity

- iii.

Age

- iv.

Education attainment (or income)

- v.

Employment (fulltime, parttime, retired, student, looking for work)

- vi.

Number living in household

- vii.

Children under 18 living in the household

- viii.

Describe your home as:

- 1.

Urban

- 2.

Suburban

- 3.

Rural

- 1.

- i.

- a.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.