The Role of Social Prescribing Interventions in Addressing Health Inequalities in the United Kingdom: A Narrative Review

Abstract

Background: Social prescribing (SP), developed in the United Kingdom through general practice, has seen varied implementation worldwide, influenced by cultural, healthcare and political contexts. Among the various efforts to reduce health inequalities among individuals and groups, social prescribing has been proposed as a key intervention. Despite growing interest, there is a need for a critical examination of social prescribing’s role in addressing health inequalities.

Aim: This study aims to review the experiences of SP service users and service providers concerning the impact of SP on health inequalities in the United Kingdom. By synthesising existing evidence, it seeks to contribute to ongoing discussions and inform future research and policy directions.

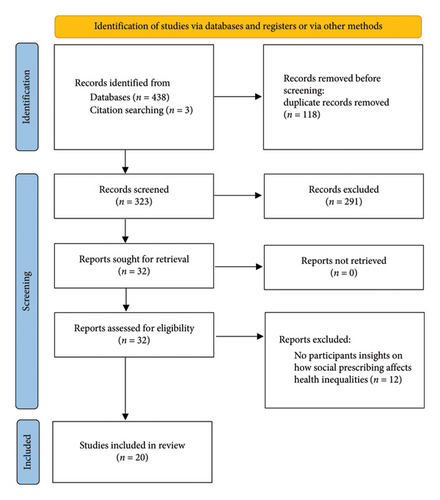

Methods: A systematic search and narrative synthesis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Databases searched included Web of Science, CINAHL, Medline, PsycArticles and PsycINFO, using keywords related to SP and inequalities.

Results: A total of 441 records were identified, with 20 papers meeting the inclusion criteria selected for analysis. The findings highlighted the positive role of SP in addressing the sociopsychological needs of patients and managing long-term conditions. Barriers included resource constraints, training limitations and accessibility challenges, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Facilitators emphasised the importance of the link worker/service user relationship, collaboration and integration.

Conclusion: SP is important in addressing health inequalities, particularly by targeting sociopsychological factors and managing long-term conditions. However, the complexity of these inequalities requires more tailored models and research. None of the studies examined SP within NHS National Health Inequalities framework such as Core20PLUS5. Future research should explore how SP interventions align with and contribute to national efforts to reduce health inequalities. Overcoming barriers such as resource limitations, training gaps and accessibility challenges, while strengthening link-worker relationships, is essential. Multisectoral collaboration and integrating SP into clinical practices are key to enhancing its impact.

1. Introduction

Social prescribing (SP) is a systematic mechanism for linking patients with community-based, nonmedical sources of support [1]. The SP approach leverages the community and voluntary sectors to offer a range of activities and practical information to address low levels of well-being and psychological issues [2, 3]. The study by Muhl et al. [4] established internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of SP through expert consensus. These definitions acknowledge the global variability in SP practices while identifying standard structural components. They clarify the role of the social prescriber/connector and emphasise a holistic approach to addressing nonmedical, health-related social needs through coproduction and community support.

Developed in the United Kingdom through general practice, SP has unique variations globally, reflecting local cultural, healthcare and political contexts [5]. Terminology varies across the United Kingdom and different sectors, but the NHS refers to these workers as link workers, a term adopted in this review [6, 7]. Customising workforce titles can aid local stakeholder engagement but hinders national and international comparisons [5].

Link workers, rolled out in general practice as part of the NHS England Long-Term Plan in 2019, support individuals with long-term conditions, mental health issues or social isolation, connecting them to services and activities that enhance health and well-being [8]. They provide nonmedical services that complement traditional medical interventions, and although there are no formal educational entry requirements, NHS link workers are expected to meet specific competencies and complete on-the-job qualifications [9].

Health is highly prioritised and valued in society as a resource for living [10]. It enables individuals to participate and function in various activities characteristic of any society [11]. There are ongoing debates about the distinction between ‘inequality’ and ‘inequity’ in health. Health inequality is commonly used in some countries to describe systematic, avoidable differences in health outcomes between social groups [12]. While inequalities and inequities are often used interchangeably in UK public discourse and academic literature, we acknowledge that they are not synonymous. Inequalities refer to measurable differences in health outcomes, whereas inequities emphasise the ethical dimension, highlighting that some differences are not only avoidable but also unfair and unjust, requiring corrective measures [13]. In this review, we primarily use the term ‘inequalities’ in alignment with UK conventions while recognising the distinct implications of ‘inequities’ in discussions of fairness and social justice.

Furthermore, health experiences can vary extensively between groups and individuals [14]. These variations are often linked to environmental, socioeconomic and individual factors, and the term ‘health inequalities’ is used to describe these differences, disparities and variations in health outcomes across different socioeconomic groups [15]. The underlying causes of health inequalities include determinants such as lack of quality education, unsafe environments, inadequate housing, limited access to good jobs, powerlessness, poverty, discrimination and their consequences [16, 17].

The WHO European Review of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) and the health divide analysis demonstrate that achieving health equity requires coordinated action across the entire government [13]. According to the review, it involves focussing on SDOH, with health ministers ensuring universal access to quality health services while advocating for health-conscious policies in other sectors.

The intersection of SP and health inequalities has become a topic of discussion in recent years. As healthcare leaders increasingly recognise the limitations of traditional medical care in addressing broader population health issues, attention has turned towards addressing patients’ social needs [18]. The authors report limitations to include inequalities in access, overreliance on medicines, neglect of patients’ social needs and the often high costs associated with treatment.

The prevalence of patients presenting to primary care with social rather than medical concerns highlights the importance of addressing the social elements of health. Approximately 20% of patients visit primary care for issues that are social rather than medical [19]. While pharmaceutical interventions have historically dominated healthcare practices, there is growing recognition of SP’s potential to address health-related issues that traditional biomedical interventions may overlook [20]. Additionally, there is a need to engage socially disengaged individuals [21].

While SP is increasingly recognised as a potential tool for reducing health inequalities, the Marmot Review, 10 years on, indicated a need for further research into the potential effects of SP on inequalities [22]. Furthermore, interventions supporting mental health during the UK COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted SP’s potential alongside other strategies, such as patient navigator programmes, group online medical visits and peer support [23]. A critical examination of the role of SP interventions in relation to health inequalities is still needed [24].

This study aims to fill this gap by reviewing the experiences of SP service users and service providers concerning the impact of SP on health inequalities in the United Kingdom. The protocol for this review was published in advance to outline the methodological approach [25]. By synthesising existing evidence, this review seeks to contribute to ongoing discussions on the nature and impact of SP in addressing health inequalities and inform future research and policy directions.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The focused research question formulated for this study was as follows: What are the experiences of SP service users and service providers concerning the impact of SP on health inequalities in the United Kingdom? We conducted a narrative review following Ferrari’s [26] guidance, which involved a systematic search and selection strategy to identify relevant literature organised according to the Population, Exposure and Outcome (PEO) framework [27]. We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to report the results and carried out a narrative synthesis involving identification of themes and interpretation [28].

2.2. Search and Selection Strategy

- •

‘Social prescrib∗’ OR ‘community referral’ OR ‘non-clinical services’ OR ‘community intervention∗’

- •

AND

- •

‘health’ OR ‘healthcare’ OR ‘well-being’ OR ‘primary care’

- •

AND

- •

‘inequalit∗’ OR ‘inequit∗’ OR ‘disparit∗’ OR ‘barrier∗’ OR ‘deprivation’.

2.3. Study Eligibility

The inclusion and exclusion criteria used for study selection are outlined in Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies presenting SP service users’ and service providers’ perspectives on SP and health inequalities, aligned with the review’s aim and research question and involved a link worker. | Studies exclusively focussing on specific activities (e.g., green social prescribing, nature-based solutions, social welfare, gardening groups or physical activity) that did not involve a link worker. |

| Studies conducted with UK participants or focused on the United Kingdom to contextualise the findings, as the term SP originates in the United Kingdom. | Studies involving non-UK participants or non–UK-based research. |

| Published between January 2013 and the end of December 2023, allowing for contemporary yet comprehensive results. | Studies published before 2013. |

| Published in English (as no translation resources were available). | Studies not published in English. |

| Peer-reviewed. | Non–peer-reviewed. |

| Empirical research, including qualitative studies, mixed-method studies (combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches) and quantitative studies. | Opinion pieces and editorials. |

The search was limited to the period January 2013 to the end of December 2023 because SP is a relatively new and evolving concept in the United Kingdom, with significant developments and widespread implementation, particularly since its rollout in England in 2019. This timeframe was chosen to capture the most up-to-date evidence reflecting current practices and understandings in the United Kingdom. Additionally, the search was restricted to English-language publications due to resource constraints, such as the lack of translation services, and because relevant literature on SP in the United Kingdom is typically published in English. Limiting the search to English also helped avoid potential bias or inaccuracies in interpreting non-English studies.

For this review, SP was operationalised as interventions where individuals are referred to nonclinical services to address health inequalities. We defined SP, for the context of this review, as a model involving a link worker, as this approach is central to the UK’s framework. Studies were selected if they defined SP in terms of a link worker, while studies that used the term ‘social prescribing’ but did not involve a link worker were excluded. This approach ensured that the review captured relevant literature and maintained a clear focus on SP’s role in addressing health inequalities in the UK context.

2.4. Study Selection and Quality Assessment

The search results were downloaded from EBSCOhost into an Excel spreadsheet, where reviewers independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to select studies. The process of study selection is illustrated in Figure 1 as a PRISMA flow diagram [29]. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by C.M. to assess their alignment with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a sample > 10% of all titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by J.D. or K.T., and full texts were reviewed by all authors. The methodological quality of all included studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [30] tool. No studies were excluded based on a quality appraisal score of seven or above. Studies were excluded for the lack of insight on how SP affects health inequalities, non-UK settings or the absence of a link worker model.

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted according to the study question using various categories, including author(s), year and country, paper title, study aims, participants, methods, findings and quality appraisal score or exceptions. A narrative synthesis was conducted, evaluating the selected studies for their suitability and relevance based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This process involved extracting findings to inform codes which were later collated into themes and subthemes and are presented in turn below. Where relevant, findings were compared between groups (service users and service providers).

3. Results

A total of 438 records were identified through database searches, with an additional 3 records obtained through backward and forward citation tracking. After removing duplicates, 323 records remained. The titles, abstracts, year of publication, target population and type of publication of these records were reviewed against the inclusion criteria, leading to the exclusion of 291 records. The full-text articles of the remaining 32 records were then assessed based on the inclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 12 articles. Ultimately, 20 papers were selected for further analysis.

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

The 20 included studies were conducted with UK participants: 14 from England, 4 from Scotland and 2 covering the entire United Kingdom. The study methodologies varied, with 18 utilising qualitative approaches, 1 using mixed methods and 1 employing multimethods. Of these studies, 11 captured perspectives from both service providers and service users, 7 focused solely on service users and 2 on service providers. A summary of the selected articles is presented in Table 2.

| Author(s), year | Study aim | Participants | Methods | Findings | Score and exceptions to quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | Examine the challenges and facilitators in SP for patients with mental health issues from the perspectives of general practitioners (GPs) in the United Kingdom | 17 GPs | Qualitative interviews | Lack of capacity, formal training and limited knowledge of local community assets were the challenges faced by GPs, whereas building patient’s trust in GPs and linking them with community services were reported as the facilitators of SP |

|

| [32] | Assess the viability of an SP intervention in improving the well-being of patients experiencing loneliness and mild mental health problems |

|

Mixed methods, including surveys and interviews | SP coordinators (SPCs) were essential in the successful functioning of the service. Several barriers need to be addressed and overcome, such as ‘buy-in’ from some GPs, branding and adequate funding of the third sector | 10/10 |

| [33] | To investigate the effective implementation process of link workers approach in general practice (GP) | Scotland-Glasgow general practice staff with responsibility for leading the link worker programme (lead GPs, CLPs and practice managers) and community organisation workers identified by CLPs (n = 83) | Qualitative process evaluation of over 2 years | Most practices were not fully embedded in the link workers programme SP and the link workers were not recognised as an immediate solution for addressing health inequalities in deprived areas |

|

| [34] | Evaluate the experience of professional stakeholders involved in SP in both the rural and urban areas of Scotland during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. | SP coordinators (SPCs) GPs, managers, researchers and representatives of third-sector organisations (n = 23) | Qualitative interviews | Findings revealed a complex SP landscape in all schemes, worked effectively during the pandemic/Shifting to online delivery was challenging but link worker priorities shifted. With GP time and services stretched to limits, GP practice-attached ‘link workers’ adopted counselling and advocacy roles |

|

| [35] | Explore the experiences and understanding of stakeholders involved in SP in Scotland during COVID-19. | Stakeholders, including professionals and volunteers involved in the SP intervention (n = 23) in the rural and urban areas in Scotland | Qualitative interviews | The results highlighted difficulties including identifying and supporting disadvantaged and vulnerable individuals, the move to digitalisation and the strains on statutory and third-sector services |

|

| [36] | To investigate the social settings and frameworks of SP interventions in the north of England | Four service users who experienced the intervention | Ethnographic techniques, including photo-elicitation interviews and extensive participant observation | Environmental context and financial capital influenced client priorities regarding the investment in services provided as part of the intervention | 9/10 relationship between the researcher and participants not fully reported |

| [37] | To investigate the Life Rooms model as an SP intervention which targets the social determinants of mental health by offering support and resources within a local community environment | Mental health service users (n = 18) from two locations in North West England, mostly from disadvantaged backgrounds | Semistructured focus groups (n = 6) | Service users reported a reduction in feelings of isolation and loneliness and enhanced feelings of productivity and safety while engaging in the Life Rooms SP intervention |

|

| [38] | Examine the level of understanding of SP practitioners regarding the social and political determinants of public health | Personnel responsible for the execution of the SP programme (n = 47), in deprived locations of Glasgow (Scotland) | Qualitative interviews | Different understanding of practitioners was highlighted in this study on how SP can tackle health inequalities. These included individual-level interventions, addressing SDOH and understanding of the social characteristics of the population |

|

| [39] | Assess the experiences and perceptions of patients with Long-Term Conditions (LTCs) who were referred to a link worker SP programme | Adults with LTCs (n = 30) (Newcastle, England) | Qualitative semistructured interviews | Participants identified a need for a holistic strategy to overcome complicated and long-term health problems (not possible in the current system of primary care). Considerations of physical, mental health and socioeconomic issues were valued by participants who actively engaged with the service |

|

| [40] | Investigate the costs and effect of a link worker SP intervention on the health and healthcare budget and its use, and the observance of the delivery process of link worker and patient management |

|

Multimethod comprising quasiexperiment and qualitative ethnography | Intention-to-treat analysis revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant reduction in HbA1c levels and a nonsignificant decrease in high blood pressure probability. Healthcare costs varied, with the intervention costing £1345 per participant. Subgroup analysis indicated more benefits for deprived individuals, ethnically white populations and those with fewer comorbidities |

|

| [41] | Examine the adaptability of an existing SP service to address the needs of clients during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and examine clients’ perceptions of changes | Clients (n = 44), link workers (n = 5) and service provider managerial staff (n = 8) in an underprivileged urban area located in North East England | Qualitative (remote) interviews | SP service providers adapted to remote service delivery, which benefitted existing clients and other vulnerable groups. Challenges included connection with those who lacked digital access |

|

| [21] | Explore the possibilities in which SP service can prove effective for individuals engaging in the SP activity | 17 service users. Sheffield, England. | Semistructured interviews | Service users reported receiving professional and personalised help to combat social problems associated with their disease conditions. Service users were engaged through various activities, enabling them to recognise their social resources along with providing them opportunities for personal growth |

|

| [42] | Evaluation of the factors influencing the uptake of SP | Stakeholders (n = 15) involved in an SP programme in the east of England | Semistructured interviews | Uptake of SP attributed to the trust of patients in GPs, the supportive guidance provided by the navigators and service providers (especially on initial call), access to free services, perceived need and the advantages of the program. Barriers to acceptance and adherence included concerns about the stigma of psychosocial issues and the program’s short duration |

|

| [43] | Assess the performance of link workers in the execution of a SP scheme along with the experiences of the participants referred to this intervention | Link workers (n = 20) and clients (n = 19) over 19 months. North of England. | Qualitative, ethnographic method | SP provided significant help for some people living with long-term health conditions. However, link workers experienced challenges in embedding SP in an established primary care and voluntary sector landscape. The organisations providing SP drew on broader social discourses emphasising personal responsibility for health, which encouraged a drift towards an approach that emphasised empowerment for lifestyle change more than intensive support |

|

| [44] | Investigate the applicability of SP for people living with long-term neurological conditions (multiple neurone disorders) | Patients (n = 9) link workers (n = 4). Northwest coast of England | Qualitative interviews | Participants appreciated the intervention and expressed interest in further engagement in community-based services. Individuals with mild symptoms were able to take part in the activities and reported improvement in their well-being. Participants with more complicated needs (e.g., mobility restrictions) encountered barriers including transport, equipment provision (mobility aids), lack of encouragement to participate and lack of self-confidence using mobility aids within the community |

|

| [45] | Investigate the challenges and barriers faced by people living with long-term neurological conditions in accessing SP | Patients (n = 17) were participants with conditions such as multiple sclerosis, fragile X syndrome, epilepsy and traumatic brain injury and family carers (n = 2). England | Qualitative focus groups | There was a lack of awareness about SP among participants. Individuals experienced difficulties encountered in service provision due to limited funding, insufficient knowledge of link workers about their condition | 10/10 |

| [46] | To investigate the implementation of a community-oriented approach to healthcare aimed at addressing the social needs of parents | Patients (n = 5000) at 17 GP practices in a town in Northwest England being covered by the community well-being practices (CWP) initiative | Case study | The CWP initiative supported > 5000 patients over four years and evidenced demonstrable improvements in a range of health and social outcomes for patients |

|

| [47] | Analyse the experiences of service users while being part of a national SP scheme known as community connectors. | Service users (n = 26). UK | Qualitative interviews | Service users reported that the scheme helped them build confidence and self-esteem to undertake daily tasks. Service users valued the company and support provided by link workers |

|

| [48] | Evaluation of an SP service | SP managers, link workers, referrers (GPs and social workers), clients, voluntary and community sector, agencies, and groups (n = 57). England | Interviews and focus groups. | Individuals had challenges in contacting agencies/groups, highlighting a need for further SP input and buddying to support initial contact. There was a need for ‘more than signposting’ |

|

| [49] | To understand processes regarding planning, implementation and evaluation of the hand in hand (HiH) SP service, acknowledged within the local community as an example of good practice | Hand in hand service (an SP initiative to alleviate social isolation/loneliness amongst older people via integration between primary care and the third sector) was evaluated in this case study. England | Case study-service evaluation | Key reasons identified for the success of the pilot phase included clarity in referral pathways, close collaboration in working among health sector and voluntary sector partners, maintenance of high-quality standards and administration, trustworthy relationship building, a well-equipped team of volunteers with up-to-date access to information resources |

|

The narrative synthesis identified three high-level themes and seven subthemes. The high-level themes are (1) SP as an intervention to address health inequalities, (2) barriers to SP as an intervention to address health inequalities and (3) facilitators of SP as an intervention to address health inequalities.

3.2. Theme 1: SP as an Intervention to Address Health Inequalities

All the included studies discussed the significance of SP in relation to health inequalities by referring to the SDOH or aiming to mitigate barriers that contribute to health inequalities among various populations.

Service users reported improvements in confidence, self-esteem and the ability to learn strategies related to managing their disease conditions [37, 43]. For those with long-term neurological conditions, access to SP interventions was seen as critical due to higher levels of anxiety and depression [45]. These findings suggest that SP can help dismantle systemic barriers faced by certain service users. In a study of professionals, participants identified a lack of understanding of the SDOH as a root cause of poor health, while a firm commitment and individualised approaches in SP were seen as key to addressing various disease conditions [38]. SP plays a role in improving access to services, mental health, self-management, health behaviours and overall well-being [2, 50].

Furthermore, studies found that SP alleviated feelings of isolation, which disproportionately affect those of lower socioeconomic status [37, 47]. SP not only facilitates access to services but also empowers individuals to overcome barriers to self-management by addressing social needs. It provided personalised support for practical problems and allowed service users to structure their time, offering a sense of purpose [21, 47].

A case study reported the effectiveness of the Community Well-being Practices (CWP) SP programme, which supported more than 5000 individuals over four years, improving a range of social and health outcomes [14]. Two studies highlighted SP’s role in addressing the complex healthcare and social needs of patients with long-term conditions. These interventions were particularly valued as SP has broader eligibility criteria, with no requirements for medical tests or other assessments, making it more accessible [39, 40]. This broad eligibility helps fill the gaps in healthcare equity, enabling individuals who might otherwise be excluded from traditional healthcare systems to access vital support.

Although service users’ experiences varied according to their disease conditions and socioeconomic circumstances, SP interventions led to improvements in glycaemic control in patients [40]. Common issues reported by service users with long-term conditions, including diabetes, asthma, coronary heart disease and epilepsy, included social isolation, depression, anxiety and lack of confidence. Socioeconomic factors often exacerbated these issues, highlighting the critical role of link workers in addressing these barriers.

Service users emphasised the importance of link workers, noting that their interactions and discussions with link workers improved their health and related issues [39]. Qualitative insights from service users highlighted how tailored interventions can significantly impact mental and physical health outcomes, illustrating the intersection of social and health inequalities. One study documented the experiences of both service users and link workers, with service users expressing appreciation for the availability of link workers and their responsiveness to patients’ needs [43].

Similarly, a study reported the positive impact of SP in alleviating social isolation and mental distress among patients with long-term neurological conditions [45]. Another study evaluated the effectiveness of the national-level SP model ‘community connectors’, designed by the British Red Cross and the Co-op. This programme aimed to provide a personalised approach to tackle loneliness and increase the impact of SP within the healthcare system. Most service users sought to regain their self-esteem and confidence, with community connector link workers helping them build the confidence needed to manage daily tasks [47]. This suggests SP can foster life skills that can lead to health improvements.

Many service users highlighted the importance of shared experiences, and the nonjudgemental culture fostered by the Life Rooms SP service programme [37]. Such environments promote increased engagement and access to supportive networks, which can help reduce health inequalities. Similarly, another study on the Hands in Hands (HiH) SP intervention found that service users reported the companionship of link workers enabled them to participate in community activities, restoring self-confidence and reducing loneliness and social isolation [49]. This suggests that SP can facilitate access and engagement with community and peer support, addressing factors that influence health inequalities.

3.3. Theme 2: Barriers to SP as an Intervention to Address Health Inequalities

3.3.1. Social Barriers

Studies have identified various social barriers that hinder the effective use of SP as a tool to address health inequalities [36, 42, 45]. For instance, financial capital was reported to facilitate a smoother experience in opting for and sustaining engagement with SP interventions, illustrating how socioeconomic status directly impacts health outcomes [36].

A lack of acceptance in social settings also emerged as a significant barrier for patients with long-term health conditions. Patients with epilepsy, for example, noted that many groups-imposed barriers upon learning of their diagnosis, while others observed changes in behaviour from those around them after disclosing their condition [45]. Similarly, societal stigma towards individuals with mental health disorders exacerbates health inequalities, as reported by Pescheny et al. [42].

3.3.2. Resource Constraints

Resource constraints are a major barrier to the successful implementation of SP programmes [32, 40, 44, 45]. Inadequate funding severely limits the delivery of SP services, which are crucial for addressing health inequalities. Many service providers view funding cuts as a significant challenge to the sustainability of SP programmes [32].

Link workers have emphasised the necessity of proper funding for community groups involved in SP, as activities for clients cannot be sustained without it [44]. Additionally, financial resource constraints faced by service users pose further challenges, with SP found to incur greater costs than traditional care for Type 2 diabetic patients, particularly those in precarious financial situations [40]. These financial inequalities widen health disparities, as those in lower socioeconomic positions are less likely to benefit from SP interventions.

3.3.3. Challenges During COVID-19

COVID-19 affected healthcare access, introducing barriers related to self-isolation and social distancing. These measures disproportionately impacted vulnerable populations, including those with preexisting health inequalities, highlighting the urgent need for tailored SP initiatives [34, 35, 41].

Link workers in deprived areas of North East England reported difficulties engaging clients during the pandemic, which limited their ability to provide consistent support [41]. GPs also encountered challenges in conducting remote consultations, delaying link workers’ efforts to connect with clients digitally [35]. Additionally, many community organisations ceased operations during the pandemic due to financial constraints, compounding barriers for those already experiencing health inequalities [34].

3.3.4. Knowledge and Training Challenges

Deficiencies in healthcare professionals’ training and a lack of awareness among service users regarding SP are significant barriers [31–33, 45, 48]. A limited understanding of local SP resources among GPs inhibits effective referrals, exacerbating health inequalities and restricting access to essential services [32]. A survey indicated that 61% of GPs were unaware of local SP organisations [32]. Similarly, a lack of understanding of the role of SP was identified as a barrier [48].

Moreover, an evaluation of patients with long-term neurological conditions revealed that many participants were unfamiliar with the term ‘social prescribing,’ which may hinder their engagement with available services [45]. Four studies support the view that training healthcare professionals and link workers can facilitate SP interventions [32, 44, 45, 48]. The role of SP coordinators (SPCs) is complex, requiring a blend of skills and knowledge to address the needs of diverse populations effectively [32, 45]. Training that incorporates an understanding of the SDOH is essential for link workers to support service users’ needs, particularly in addressing health inequalities [44, 48].

3.3.5. Accessibility and Adaptability Barriers

Accessibility and adaptability issues were highlighted in two studies [45, 47]. Physical barriers, such as inadequate access to buildings and a lack of adapted facilities for individuals with disabilities, prevent equal participation in SP activities, thereby perpetuating health inequalities [45]. Furthermore, limited public transport links restrict access to community connector programmes, further exacerbating health inequalities.

3.4. Theme 3: Facilitators of SP as an Intervention to Address Health Inequalities

3.4.1. Relationship Between Patient and Link Workers

Three studies have identified the relationship between patients and SP coordinators as crucial facilitators of SP interventions [39, 47, 48]. The quality and depth of the relationship between SP service users and link workers are essential for promoting well-being and addressing health inequalities.

It was reported that long-term health conditions and health-related behaviours could be positively modified by setting progressive, realistic and personalised mutual goals, along with receiving regular social support from SP link workers [39]. White et al. [48] emphasised the importance of fostering meaningful relationships among service providers, link workers and coordinators to achieve outcomes that effectively address health inequalities. Thompson et al. [47] also noted that the relationship between service users, link workers and volunteers was considered the most significant aspect of SP programmes, with users valuing the companionship offered by link workers and volunteers.

3.4.2. Primary Healthcare Collaboration With Link Workers and Community Organisations

Two studies reported a positive effect of collaboration between primary healthcare and community organisations, highlighting that most stages of the SP process are influenced by the extent of collaboration between the healthcare system and community groups [31, 32].

Bertotti et al. [32] found that inadequate interactions between GPs and SP organisations led to fewer referrals, which can exacerbate health inequalities. Similarly, Aughterson et al. [31] reported that formal collaboration between GPs, practices and community organisations is critical for the successful implementation of SP interventions, which can help mitigate health inequalities.

Additionally, White et al. [48] highlighted that the trust patient’s place in GPs is a key factor in enhancing the likelihood of primary care patients engaging in SP programmes, thereby contributing to the reduction of health inequalities. Successful implementation of SP interventions was linked to GP engagement, collaborative leadership, strong team dynamics and support from link workers, all of which can contribute to addressing health inequalities within the population [33].

4. Discussion

Our systematic search identified 20 articles that directly addressed our research question: What are the experiences of SP service users and service providers concerning the impact of SP on health inequalities in the United Kingdom? We explored this under three themes: (1) SP as an intervention to address health inequalities, (2) barriers to SP in addressing health inequalities and (3) facilitators of SP as an intervention to address health inequalities.

A significant number of studies focused on the mental health needs of patients. Many studies [51–56] reported that SP interventions effectively addressed the complex needs of individuals with mental health issues. Meta-analyses of various studies [50, 57] found improvements in overall health status, social behaviours and self-care among SP service users, particularly those from socioeconomically deprived groups.

The psychosocial challenges associated with long-term conditions, including poor well-being, social isolation, loneliness, depression and anxiety [58], further complicate the landscape of health inequalities. Calderón-Larrañaga et al. [59] observed that rising health issues contribute to increasing social inequalities, positioning SP as a potential tool for improvement. While previous research [60] has established correlations between social isolation and increased risks of depression, coronary heart disease and stroke, the literature lacks clarity on the causal relationships between SP and measurable health outcomes. This gap highlights the need for further research to rigorously investigate these connections.

While nearly all studies reported a positive role for SP in addressing the sociopsychological needs of patients from deprived backgrounds and managing long-term conditions, Gibson et al. [36] questioned whether SP effectively alleviates health inequalities due to the ‘classed perspective’ shaping clients’ experiences. This ‘classed perspective’ refers to how socioeconomic status and class influence access to resources and services, affecting health outcomes. This raises important questions about the assumptions underlying SP as a universal solution for health inequalities, emphasising the need to contextualise its contributions. While link workers play a role in connecting individuals to community resources and may impact structural health inequalities such as poor housing, racism and unemployment. However, they cannot resolve these systemic issues alone without facilitators and enablers.

The increasing prevalence of long-term conditions in an ageing population highlights the need to address SDOH [61]. However, a comprehensive approach is essential, one that addresses these determinants directly rather than relying solely on SP [62]. While link workers can mitigate some of the effects by assisting clients in navigating complex systems, broader efforts are required to address the root causes. A multiagency approach, involving healthcare providers, social care agencies and local governments, is necessary, along with cultural competency training for link workers to effectively address issues such as racism and promote equity in care.

Furthermore, Themes 2 and 3 highlight various barriers and facilitators that influence the effectiveness of SP in addressing health inequalities. These findings suggest that certain conditions must be met to optimise the impact of SP interventions. Despite the positive outcomes, numerous studies have identified significant barriers to the effective implementation of SP. Issues such as inadequate resources, training deficits and knowledge gaps among link workers were highlighted by Bickerdike et al. [2]; Longwill [63]; White and Kinsella [64]; South et al. [18] and Woodall [65]. Featherstone et al. [66] emphasised shortages of tangible resources, including funding and staffing. Additionally, challenges posed by the pandemic, as reported by Younan et al. [67]; Kim et al. [68] and Westlake et al. [69], further complicated the implementation of community work and SP interventions.

Conversely, key facilitators, such as strong relationships between link workers and service users and adequate training and support [70, 71], were found to enhance the effectiveness of SP.

Not all SP interventions positively impact health inequalities, and some could introduce unintended consequences, such as inequalities in access and support. Accessibility and adaptability challenges [72, 73] may exacerbate existing inequalities rather than mitigate them. Thus, while SP holds promise, its implementation must be carefully managed to avoid negative consequences.

None of the studies included in this review from England referenced the NHS England national approach to reducing health inequalities, Core20PLUS5, introduced in 2021 [74]. This is noteworthy, as, since the roll out of SP link workers into the NHS in England through the Long-Term Plan in 2019 [8], there has been a national policy focus on reducing health inequalities. Furthermore, the 2022 Health and Care Act [75] introduced integrated care systems (ICSs), tasked with reducing health inequalities and coordinating care across multiple services. The Core20PLUS5 national approach targets the 20% most deprived populations and specific clinical conditions, but our review did not include studies from England that evaluated SP within this national framework nor was it acknowledged.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Our review has strengths and limitations. Among the strengths are the systematic search strategy and the focus on high-quality studies relevant to the UK context, particularly a specific model of SP involving a link worker. We concentrated on peer-reviewed studies to ensure the highest level of evidence and rigour.

A limitation of this review is the restriction on the search year range. While this decision was made to balance comprehensiveness with contemporary relevance, there is a small possibility that important earlier studies were excluded. However, this risk was mitigated through backward and forward citation searches, ensuring that key relevant literature was identified. Additionally, excluding grey literature may have limited the comprehensiveness of the review, especially in a field like SP where non–peer-reviewed sources can play a significant role.

4.2. Recommendations

Future research and SP policy should address the integration of SP programmes with the NHS England Core20PLUS5 approach and other national policies aimed at reducing health inequalities, exploring how SP aligns with the objectives of ICSs in tackling health inequalities. This will enable a better understanding of how policy influences SP’s impact on health inequalities, as well as the barriers and facilitators identified in the review.

Additionally, future research should focus on understanding how SP can be adapted to align with evolving national health policies, addressing any implementation challenges that arise. Context-specific studies are also recommended to better understand the impact of the link worker model on healthcare-related inequalities and to tailor interventions to meet diverse population needs more effectively. Comparative studies from Wales, Northern Ireland and international contexts are recommended. Since this review focused exclusively on models involving a link worker, future studies could explore other SP models and update the timeframe to verify or refine these findings.

Research should also identify specific strategies to overcome barriers, aiming to make SP more effective in meeting both practical and mental health needs. Greater exploration of the enablers and facilitators of SP is needed, as understanding these factors will empower patients, healthcare professionals, link workers and service providers to improve outcomes. In addition to overcoming barriers, future research should distinguish between addressing health inequalities and health inequities. Research should evaluate how well SP aligns with health equity principles and whether it addresses inequities in addition to broad inequalities.

Studies should also examine the relationship between SDOH and healthcare-related inequalities across different SP models. Analysing these relationships will help understand their impact on healthcare inequalities in terms of access, care and outcomes. Since service users identified their care experience as a significant factor in improved outcomes, SP services should clearly define the types of health inequalities they address. This clarity is crucial, as interpretations of health inequalities vary across studies, allowing for more targeted research and effective implementation.

A scoping review found that SP interventions lacked theoretical frameworks to inform service design [76]. Moreover, there is a need to develop theories and well-defined ontologies to guide research and practice in SP. This will ensure interventions are evidence-based and capable of addressing the complexities of health determinants. Multisectoral collaborations, involving healthcare professionals and community services, should be promoted to create a holistic approach to SP training and support should be provided to practitioners, helping them identify specific evidence-based interventions, engage patients and refer them to the SP intervention best suited to their needs. Finally, integrating SP into clinical practices is recommended to ensure the seamless delivery of services to target populations, reducing the need for isolated initiatives.

5. Conclusion

Our review examined the ongoing debate on the role of SP in addressing health inequalities, focussing on the perceptions of both service users and service providers. The findings identify SP as a tool for addressing various health-related inequalities, including challenges in accessing healthcare, experiences with health services and the management of long-term conditions and well-being. However, our analysis also revealed several barriers that hinder SP’s effectiveness in addressing health inequalities, such as training and capacity limitations among stakeholders, resource constraints and challenges related to emergencies and accessibility. The multifaceted nature of health inequalities, differing interpretations of these inequalities and the complex relationship between SDOH and healthcare inequalities complicate SP’s role and suggest that its impact may not be generalisable across all contexts. Therefore, more context-specific studies are necessary to better understand the effects of the link worker model of SP on healthcare-related inequalities and to tailor interventions that effectively address diverse population needs.

Disclosure

This work was undertaken as part of a PhD programme at Birmingham City University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this study. Open-access publishing was facilitated by Birmingham City University as part of the Wiley–Birmingham City University Agreement.

Acknowledgements

Open-access publishing was facilitated by Birmingham City University as part of the Wiley–Birmingham City University Agreement.