Balancing Compassion and Self-Care: Insights From Palliative Care Professionals and Volunteers

Abstract

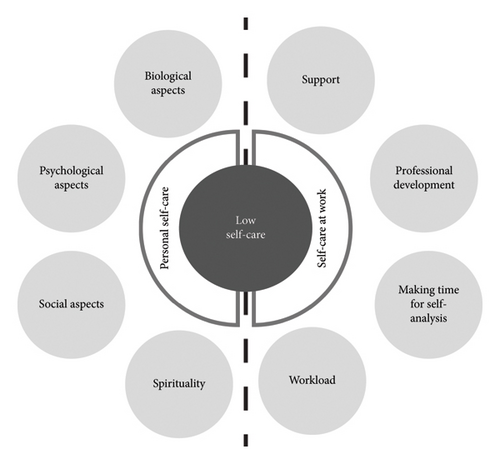

Working in palliative care is both an exhausting and an enriching experience. Self-care is vital because it protects against the risk of developing burnout and predicts higher quality of life levels. Self-care is a shared responsibility between the individuals and their contexts. This qualitative study aimed to understand the self-care practices of Ecuadorian palliative care teams and design a self-care self-planning tool for local volunteers, students, and professionals. A total of 71 individuals participated in 10 focus groups in four cities in Ecuador. Data were analyzed through thematic analysis. The results provide a comprehensive overview of the self-care strategies employed by palliative care professionals, volunteers, and students who have concluded internships within the field. These strategies could serve as mechanisms to manage complex situations and promote healthy and satisfactory scenarios. Results indicate a low self-care practice in the personal and professional realms. With that in mind, the results were divided into two main themes. For personal self-care, participants referred to the importance of spirituality and biological, psychological, and social aspects of self-care. On the other hand, for self-care at work, people emphasized the importance of support, professional development, making time for self-analysis, and managing workload. Developing practical approaches requires a holistic perspective that considers contexts, overcomes barriers, and promotes practices that support professionals’ physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Using the insight from the results, we provide a tool to facilitate personalized self-care planning.

1. Introduction

Professional quality of life encompasses compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue [1] and is fundamental when caring for people in palliative care (PC). On the positive side, professionals experience compassion satisfaction from the happiness of helping others and recognizing the positive impact of their work on patients and their families [2]. Compassion, the emotional response triggered by witnessing suffering, motivates healthcare and social care professionals to alleviate it [3, 4]. Compassion is crucial in PC for providing dignified end-of-life care [5]. It has been shown that volunteers in PC also experience high levels of compassion satisfaction [6]. Traits such as kindness, empathy, and openness significantly contribute to compassion satisfaction [7].

Despite these positive aspects, people working in PC also face overwhelming personal and institutional situations [4], emotional challenges, and complex situations that can lead to compassion fatigue, negatively affecting job satisfaction, patient care, and overall quality of care [8]. Compassion fatigue includes burnout and secondary traumatic stress [1]. Ancinas [9] refined Figley’s [10] definition of compassion fatigue, describing it as the natural, predictable, treatable, and preventable consequence of working with suffering individuals, resulting from the emotional residue of exposure to working with those who suffer from traumatic episodes. Stressors like heavy workload, poor communication, and exposure to death contribute to this exhaustion [11, 12]. Results from various studies on healthcare personnel worldwide indicate moderate to high levels of compassion fatigue [13, 14], a factor that raises concerns about the quality of life for these formal caregivers. However, some authors, such as Sinclair et al. [15], are critical of the concept, arguing that it may divert attention from other equally important negative aspects in healthcare professions, such as burnout, secondary traumatic stress, countertransference, and vicarious traumatization.

Working in PC is both exhausting and enriching [8], highlighting the need for effective self-care strategies for those in constant contact with suffering and death [16]. Sapeta and colleagues [17] identified four primary coping strategies for PC professionals dealing with the psychospiritual demands of end-of-life care: proactive coping, self-care (including self-protection and self-awareness activities), self-transformation (accepting limits), and finding deep professional meaning. Current research supports that these strategies are protective factors that enhance the psychosocial welfare of PC professionals [11, 18, 19]. Other effective strategies to reduce compassion fatigue include PC training, improved communication, spiritual meaning, boundaries, colleague support, reflection, exercise, social activities, acceptance [16, 20], and maintaining compassion without becoming overly involved [17].

Self-care encompasses proactive and responsive behaviors that enhance health and well-being [21]. It involves managing conflicts and improving mental health through self-confidence, organization, planning, and control [17, 22]. This continuous effort includes activities within and outside the work environment, integrating these behaviors into daily routines [12, 17, 23]. Notably, self-care practices like mindfulness and maintaining a balanced lifestyle significantly improve the quality of life for PC professionals [23]. Self-care protects against burnout, compassion fatigue, and work stress, enhancing overall well-being [24, 25].

Effective self-care actions encompass a balanced diet, proper sleep, recreational activities, yoga, reflection, rest, hobbies, nature contact, emotional support, family time, social life, meditation, spirituality, and professional disengagement during free time [17, 26]. Other strategies include self-knowledge, physical self-care, social aspects, support networks, and behavioral untying [26], self-compassion, purpose, support structure, mindful self-awareness, relaxation, and supportive relationships [24, 25]. Informal and mindful self-care practices incorporated into daily routines are also linked to lower burnout risks [11, 17, 19]. Specialized training in emotional management, spiritual self-management, self-knowledge, and empathy helps professionals constructively transform their experiences, improving their quality of life and care [17, 19]. Emotional intelligence and social support are additional protective factors against work stress and compassion fatigue, enhancing communication, empathy, and self-awareness [27, 28].

Self-care is a shared responsibility between the work environment and the individual. Designing psychosocial risk prevention programs focused on self-care practices and fostering a proactive and positive working culture is essential [11, 29]. In fact, team collaboration and support from top-level executives are fundamental for improving job satisfaction and care quality [8, 19, 29]. The COVID pandemic has underscored the need for ongoing team support, resilience, and well-being, with institutional policies prioritizing personal well-being [29].

Given the complexity of PC and the factors affecting professional quality of life, authors have highlighted the need for a deeper understanding of how self-care is perceived [21]. Despite the recognized benefits of self-care, there is a lack of research on its role within the Ecuadorian cultural context, particularly among healthcare and social care teams that regularly involve professionals, volunteers, and students in preprofessional practice within those teams. Understanding how self-care is perceived and practiced in Ecuador is important for developing culturally appropriate strategies that support the well-being of healthcare workers in this country. Understanding self-care practices in the Ecuadorian context will aid in developing effective strategies for local professionals. Thus, the current research aims to understand the self-care practices within PC teams in Ecuador and design a self-care planning tool for local volunteers, students, and professionals.

2. Materials and Methods

This research originated from a project funded by the University of the Balearic Islands and the Govern de les Illes Balears (OCDS-CUD2022/04) aimed to develop self-care training for PC team members in Ecuador. As a preliminary measure, a qualitative study was conducted to comprehend self-care practices within PC teams in Ecuadorian culture and design a tool for self-care self-planning at an individual level for all volunteers, students, or professionals operating in this sector.

2.1. Design

In this qualitative study, focus groups (FGs) were the primary data collection method. By utilizing FGs, participants’ perspectives and experiences were captured collectively, enhancing the overall comprehension of the issues addressed.

2.2. Participants

The sample comprised 71 participants, including 13 men and 58 women, with a mean age of 40.2 years. The average tenure within the PC sector is 9.33 years Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the sampled participants. Participants were recruited through a nonprobabilistic convenience sampling, where the Ecuadorian Association of Palliative Care (ASECUP) notified its members via email. Additionally, two local universities distributed mailings to senior healthcare and social care students. Interested individuals registered to participate in the FGs using an online form and were provided with a formal invitation letter detailing the study. Inclusion criteria encompassed the following: being volunteers in PC, final-year students, or professionals in related healthcare and social care disciplines with experience in PC; being aged 18 or above; and being willing to partake in the FG.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship with palliative care | ||

| Students | 15 | 21.2 |

| Volunteers | 6 | 8.4 |

| Professionals | 50 | 70.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 58 | 81.7 |

| Men | 13 | 18.3 |

| Area | ||

| Medicine | 23 | 32.4 |

| Nursing | 18 | 25.4 |

| Nursing assistance | 2 | 2.8 |

| Nutrition | 2 | 2.8 |

| Occupational therapy | 2 | 2.8 |

| Psychology | 11 | 15.5 |

| Rehabilitation | 4 | 5.6 |

| Social work | 7 | 9.8 |

| Spiritual care | 1 | 1.4 |

| Working unit | ||

| Public sector | 15 | 21.2 |

| Private practice | 5 | 7 |

| Nonprofit organization | 42 | 59.1 |

| Private for-profit | 9 | 12.7 |

2.3. Data Collection Methods

In September 2022, 10 FGs were conducted in four cities across Ecuador (Quito, Loja, Cuenca, and Guayaquil). Each FG comprised a mix of students, PC volunteers, and professionals, encompassing physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and nutritionists. Following the recommendations of multiple authors, the sessions had an approximate duration of 1–2 h each [30]. The facilitation was led by two PhD candidates in Education with experience in group dynamics, one male and one female. The facilitators actively encouraged group engagement and dialogue by following the interview guide and introducing new questions when necessary to facilitate the ongoing process [31]. This guide was not previously shared with the participants. The interview guide included three main themes: professional quality of life (e.g., “Describe some experiences from working in PC that have been enriching for you,”), self-care (e.g., “What do you consider to be your most helpful and least helpful coping techniques and self-care strategies?”), and training (e.g., “What training strategies do you consider most interesting and useful to incorporate self-care practices into your daily life?”).

The FG approach was preferred over individual interviews as it encourages participant interaction, promotes other viewpoints, and helps identify areas of agreement and differences within the group, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the study topic. The groups, as advised [32], had an average of 7 participants. The selection of group locations was guided by convenience and proximity [33]. Before commencing the FGs, participants received a comprehensive explanation regarding the ethical aspects of the research, ensuring their informed consent. Then, the sessions were audiorecorded for subsequent analysis. Participants’ names were anonymized by the number of the focus group (FG) they were part of, followed by a number (P).

2.4. Data Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed and then subjected to qualitative analysis. Transcripts were not returned to participants. A thematic analysis approach was employed to discern and classify the various self-care practices related to the professional quality of life among participants. This method seeks to comprehensively understand the meanings and experiences expressed by participants, facilitating the identification of patterns, trends, and emerging themes within their responses. Due to its inherent theoretical flexibility, thematic analysis serves as a versatile and valuable research tool, enabling the provision of a rich and detailed yet complex account of the data [34]. The following steps were undertaken: (1) familiarization with the data; (2) generation of initial codes; (3) exploration for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and labelling identified themes; and (6) producing the report [34]. Three of the authors (M.E.C.-C., J.F.C.-V., and P.H.-A.) oversaw the analysis. They all were familiar with the transcriptions, one (M.E.C.-C.) identified the initial codes and exploration of themes independently, and then the three conducted the final three steps. The analysis was conducted using the Atlas-ti software.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat de les Illes Balears (File: 274CER22). The ethical principles of confidentiality, informed consent, and respect for the rights of participants were strictly adhered to.

3. Results and Discussion

The analyses from the FG indicated low self-care practices among Ecuadorian PC teams. The themes highlighted in the professional realm were support, professional development, making time for self-analysis, and managing the workload. On the other hand, regarding personal self-care, we found that spirituality and social, psychological, and biological aspects of one’s life are essential. Figure 1 shows the themes and codes analyzed in this section, and Table 2 presents the percentage of discussion groups in which each topic was mentioned and the rooting, which indicates the frequency with which discourse fragments (verbatims) related to each theme appear throughout the analysis. These indicators help assess the relevance and weight of each category within the study. The rest of the section delves into each theme.

| Themes | Description | No. of groups discussing the themes | Frequency (%) | Rooting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing care | Low self-care | Self-care is recognized as important, but participants do not practice it routinely. | 8 | 80 | 17 |

| Self-care at work | Support | Support networks such as therapy availability, supervision, and peer mentoring. | 6 | 60 | 20 |

| Professional development | Training oneself and training future professionals on self-care. | 4 | 40 | 15 | |

| Making time for self-analysis | The importance of using self-awareness as a self-care instrument. | 5 | 50 | 22 | |

| Workload | Organizational policies and personal limits influence the management and perception of the workload. | 6 | 60 | 23 | |

| Personal self-care | Biological aspects | Self-care practices that are aimed at taking care of the body or physical self. | 10 | 100 | 48 |

| Psychological aspects | Self-care practices that cultivate positive emotions and thoughts of oneself and the circumstances. | 10 | 100 | 55 | |

| Social aspects | Bonds with friends and family as a pillar to support professionals, students, and volunteers in their self-care. | 9 | 90 | 57 | |

| Spirituality | Self-care through inner peace and connections with higher values and, in some cases, God. | 10 | 100 | 63 | |

The outcomes resulting from the FG analysis offer a comprehensive overview of the self-care strategies employed by PC professionals and volunteers, along with students who have concluded internships within the field. These strategies could serve as mechanisms to manage burnout situations and promote healthy and satisfactory scenarios. Our results indicated that self-care goes beyond “giving oneself permission to take the time, to make the commitment, and to negotiate the roadblocks” or being a “complementary practice when leaving work and generally associated with the physical (sports) or social (family, friends) aspect.” As Benito and colleagues refuted [19], it actively involves the person, the team, and the institution.

3.1. Low Self-Care

“When we cannot sleep or have high blood pressure, we realize that we have not taken care of ourselves. Self-care should be taught at university. Because then the student will learn ‘it is true; I am a human being like any other, and I have to take care of myself’”(FG10-P6).

“Monday to Friday is impossible for me [to practice self-care]. I have three children. It’s complicated because I get off work and then I have responsibilities at home: homework, being with the children, (…) I don’t have time for anything else” (FG6-P5).

It seems crucial to prioritize self-care and then employ self-care strategies [23, 25]. In our sample, the recognition of the significance of self-care predominantly arose when participants felt a noticeable decline in their well-being. During these instances, endeavors were undertaken to implement self-care strategies, frequently adopting a short-term, problem-solving approach. Nevertheless, after this reactive reaction, a recurring pattern emerged wherein the familiar routines regained precedence over self-care to answer the demands of daily life.

3.2. Self-Care at Work

Adequate self-care translates to better care [35]. Organizations must foster proper working conditions and environments so people can fully embrace self-care practices [12]. Our analysis revealed a complex and nuanced reality in which many of the elements inherent in the work environment are beyond the individuals’ change. Their transformation does not depend solely on the will of the employee or volunteer. This section highlights vital elements such as feeling supported at work, professional development, self-awareness, and workload management.

3.2.1. Support

Throughout the group discussions, a significant emphasis on the role of peer and managerial support in professional self-care surfaced. As the findings were further examined, it became apparent how this support network at work held crucial importance in managing the emotional and physical demands of this challenging work environment. A study conducted by Arantzamendi et al. [37] emphasizes the essential role of coping skills in PC and proposes a five-step process, highlighting the importance of teamwork, particularly within “micro-teams of strength,” and self-care as key factors.

Consoli et al. [38] and Moe and Thimm [39] indicate that therapy has emerged as an indispensable resource. It is known that personal psychotherapy can be a central element of ongoing self-care. For many, this platform for reflection and dialogue offers a necessary respite from the intricacies of the work environment. The chance to converse with an external figure, someone not directly associated with the unit, became a fundamental tool for addressing discomfort and discovering a realm for emotional recuperation. However, Ecuador does not have the appropriate sociostructural conditions to guarantee proper mental health services, and the lack of financial resources is a barrier to accessing them [40]. The provision of free therapy within work units could lessen the burden for those unable to afford it independently. This disparity uncovers the significance of ensuring that self-care opportunities are accessible to all, irrespective of financial capacity.

Another theme was supervision. Previous research has argued that clinical supervision is not always available and may be effective for many, but not for others [23]. In our sample, supervision was positioned as a crucial support element in complex situations. The opportunity to share and receive guidance from more experienced colleagues or supervisors provided a valuable perspective and the chance to integrate a deeper understanding of the emotional implications of work. The testimonies underlined the need to sustain this practice in the workplace over time. One participant expressed the importance of supervision given that, “it taught you that what happens in your life affects what you do. And you can only work here if you give your vision of what all this means in your life, who you are” (FG10-P5).

Peer support is another fundamental pillar of self-care at work. Formal and informal debriefing appears as an effective strategy for self-care [23], and coaching seems to have significant advantages [41]. As seen in previous research [8, 12, 18], the existence of a strong work team, where members can trust each other and share their feelings and experiences, creates an environment that fosters belonging and mutual support. These bonds strengthen decision-making, problem-solving, and coping with daily challenges. For participants, collaboration and emotional support were essential tools in the fight against isolation and burnout. In fact, a participant highlighted that “the most enriching thing (…) it’s knowing that I have my partners for the decision-making or when something goes wrong in my life” (FG2-P8).

3.2.2. Professional Development

A limited number of respondents (3 out of 71) held a specific perspective on training within the context of self-care. These professionals emphasized how acquiring specialized knowledge and skills within their field of work significantly contributes to their well-being and proficiency in their roles. For them, training surpasses the acquisition of technical skills; it also signifies a personal commitment to enhancing their self-confidence and the caliber of their work. This view is supported by previous research that shows that professional courses for improving clinical abilities might serve as a good coping strategy because they could increase self-efficacy [42].

Another aspect highlighted by one participant was the concept of training future professionals and mentioned “You are responsible for giving them a solid foundation so that PC continues to improve” (FG2-P1). This perspective extended beyond the individual level and was framed by the notion of leaving a legacy and contributing to the advancement and continuity of the profession. Investing in training and mentoring students evolved into a form of long-term care. This notion relates to how finding deep professional meaning can be a coping mechanism for PC professionals [17].

3.2.3. Making Time for Self-Analysis

“Recognizing and responding to the nuanced situations” [2] is essential when working in PC. Our participants’ accounts unveiled a network of interconnected strategies, highlighting self-awareness as a fundamental self-care instrument. Researchers argue that self-awareness is the best tool one can cultivate [19]. As some participants pointed out, having time for checkups and paying full attention to yourself to know how you are and how different situations affect you is fundamental. “It would be like knowing your emotions and seeing how your body is physically. Because, in the end, the body speaks for us” (FG2-P8).

These components (personal self-awareness, self-reflection, self-analysis across various moments, and awareness of one’s own discomfort) are interwoven in a reflective process demanding time and commitment to comprehend, recognize, and adeptly tackle distress [11]. As in Cañas-Lerma et al. [6] research, in this line of work, the awareness of one’s own reality and that of others who might be living a complex medical situation might help put their problems into perspective. Research with PC nurses also points out how working in PC positively affects their lives due to the daily hard situations they care for [18].

“What am I doing now that I feel sad? Why did I try to hide it by telling jokes? (…) [it is important] to understand why I do this or that, or why I think this or that, or explain what you do and what you feel… to know yourself better” (FG1-P3).

Awareness has been identified as a buffer for the negative impacts of working in PC [11]. It has also been previously noted as a predictor for competence in coping with death, high compassion satisfaction, and lower compassion fatigue and burnout [11]. Higher awareness might be related to having more experience in PC, which has been shown to increase compassion satisfaction [16, 20]. On the other hand, research with volunteers in PC shows that the suppression of their own emotions is a common practice [6]. Recognizing that professionals and volunteers are human beings with lives and vulnerabilities is the foundational step for any successful intervention. This receptiveness to comprehending their emotions and acknowledging the cues their bodies convey establishes a groundwork for self-regulation and emotional care.

3.2.4. Workload

Previous research [12] has noted that nurses’ perceptions of their bad state of health might be due to organizational time constraints, such as work schedules and leaves. Institutional policies and poor working conditions, including heavy workloads, are risk factors for PC professionals [17]. In our research, various factors that shape the work environment, including the patient load, the strict protocols to be followed, and the distribution of holidays and vacation periods, constitute elements outside the direct influence of employees and volunteers and affect how they practice self-care.

Nevertheless, the results uncovered one aspect that falls within the employee’s control: whether to bring work home. Throughout the participants’ accounts, there was a strong sense of the importance of establishing a solid boundary between the work and personal spheres. For many, this differentiation has become a crucial foundation of self-care. Avoiding bringing work issues home was a fundamental strategy for maintaining balance and emotional health. In sum, the statement “I don’t particularly take work home” (FG6-P7) was central for this workload management.

3.3. Personal Self-Care

3.3.1. Biological Aspects

Within the realms of social health sciences and PC, the need for care centered on physical self-care emerges. This practice extends beyond medical considerations, positioning itself as a pivotal facet of holistic well-being. Physical and mental rest emerged as an additional key component of self-care. Participants’ voices emphasized the significance of granting themselves moments of disconnection, rest, and recovery that nourish the essence of the individual and promote optimal readiness to confront the challenges posed by occupational and personal obligations. These practices also encompassed components like physical activity, a well-rounded diet, and adequate rest. Although the physical dimensions of self-care are sometimes not statistically related to compassion fatigue or burnout [43] or have a small effect on well-being variables [44], participants in our study underscored the significant role of these elements in effectively addressing the challenges inherent to their work and environment. One expressed how it helps him, “On a physical level, I do physical activity to get rid of the overload or the bad mood. I do a lot of running, and that lowers my stress levels. The stress level goes down, and so do the headaches” (FG4-P3).

In the sphere of physical care, a striking diversity in participants’ preferences became apparent, influenced by the broad array of activities ranging from high-intensity sports to more serene approaches. Certain participants opted for vigorous pursuits such as running or cycling, while others discovered equilibrium through contemplative practices like yoga or walking. The array of choices within this spectrum is contingent upon individual factors, encompassing considerations ranging from time limitations to personal inclinations. Notably, it is intriguing to emphasize the emergence of dance as a liberating avenue for numerous participants, affording them a fleeting yet impactful release through the fusion of movement and music, elements deeply rooted in Latin American culture. As a participant mentioned, “I love to dance. I create my own choreographies, I dance at home, and it relaxes me” (FG6-P7). Dancing has also been suggested as a creative way to relieve stress [45].

The significance of nutrition is acknowledged regarding dietary practices, although it is accompanied by nuanced challenges in execution. Certain participants recognized the prevalence of poor dietary habits as an inherent cultural and systemic element entrenched within their surroundings. Despite the challenges, there was a collective recognition of nutrition’s vital role as a foundational component of self-care [44]. Awareness of its impact on health and well-being encouraged the search for solutions that balance everyday demands with more conscious food and dietary decisions.

3.3.2. Psychological Aspects

Internal self-care acts as a protector against the inherent stressful characteristics of PC work [12]. The testimonies highlighted how attention to personal image, from makeup to hair care, is presented as a way of renewal and relaxation. The time invested in these practices reflects an investment in oneself, a space in which an internal reboot is allowed. A participant indicated, “Putting on make-up, always being well presented. Sundays are sacred, and in my house, they already know that I lock myself in my room, and I put on the mask, I put on the oil, I do my eyelashes, and nobody interrupts me; it’s my moment. It renews me” (FG8-P1).

Beyond the physical dimensions that may affect self-concept and self-esteem, participants also sought mental relaxation in their daily lives. Relaxing activities such as painting, listening to music, or playing a musical instrument were indispensable to alleviate stress and divert the mind from constant pressures. These instances of respite furnished a space for emotional catharsis and the pursuit of inner tranquillity. To “disconnect” a participant shared that “when driving, I distance myself from what I was distracted by, and I felt that it relieved me of the discomfort I was going through” (FG1-P4).

The concept of personal reward also surfaced as a motivator for confident choices and self-kindness [46]. Participants acknowledged the significance of indulging in personal pleasures, even when these do not align with conventional notions of health. Sweets, alcohol, and food emerged to commemorate small victories and counterbalance less enjoyable experiences. This aspect of personal reward evolved into a self-care strategy that harmonizes momentary gratification with a cognizance of self-regulation.

The cultivation of an inner life is also a buffer against vicarious trauma and could enhance job satisfaction and therapeutic effectiveness among PC professionals [11]. Participants in our study acknowledged the necessity of allocating time for the mind to unwind and reclaim a state of tranquillity. This approach held fundamental significance in reinstating inner equilibrium and fostering readiness to confront everyday obstacles from a fresh perspective. Here, a connection between music and emotional expression constituted a profoundly meaningful bond. Music evolved into a conduit for release, enabling individuals to establish a connection with their emotions and channel their encounters. This proactive method of self-exploration and self-regulation emerged as a valuable instrument.

3.3.3. Social Aspects

How healthcare activity is organized involves great personal and social sacrifice [12]. Previous research has shown that structural variables interfere with self-care development, especially in the physical and social dimensions [12]. In the absence of supportive elements within the work environment, participants sought connections beyond this setting. Friends and family emerged as crucial figures with whom they share their instances of professional unease or discomfort. Having a support network external to work served as a mechanism for emotional relief and liberation, demonstrating how the need to share and express is intrinsic to self-care.

Building and maintaining social relationships emerged as crucial cornerstones of self-care strategies [47]. Within this research, the significance of cultivating relationships or connections with friends and family held relevance, particularly when emotional challenges must be faced. A participant exemplified how she felt relieved by having someone to talk to and mentioned: “Unload, yes, yes, unload; when you leave the hospital, you need to talk to your family or friends. Talking [helps]” (FG1-P3).

The aptitude to share moments with cherished individuals translated into a profound feeling of belonging, furnishing an emotional refuge amidst the stresses of the work environment. The social network is consolidated as a realm of understanding and support. Participant’s accounts mirrored how, within the inherent stress of PC work, the chance for de-escalation and relaxation through engagement with friends and family emerges as a vital avenue for rejuvenation, furnishing emotional and mental recharging. Engaging with family and friends served as a conduit for releasing and exchanging thoughts and emotions. Conversations and personal interactions gained a therapeutic essence, enabling professionals to express their worries and experiences. This, in turn, aided in releasing the emotional weight that accompanies their labor. A participant said, “in the most challenging moments, my friends help me to know how to escape (…) [PC] is beautiful work but it is exhausting” (FG2-P2).

3.3.4. Spirituality

Exploring spiritual aspects revealed a significant link between self-care and the spiritual dimension, whether within the Catholic religious framework rooted in Ecuadorian culture or through broader approaches such as meditation and nonreligious spirituality. As participants described, these perspectives provide a crucial space for the search for meaning, comfort, and peace during the challenges of PC.

Research with informal caregivers in Latin America has not found associations between religious involvement and quality of life [48]. Other studies have found an association between negative spiritual/religious coping, such as dissatisfaction with a religious representative and negative revaluation of God or meaning, and depressive symptoms in informal caregivers [49]. In our sample, however, for those participants who embraced the Catholic religious practice, spirituality emerged as a refuge and comfort amid moments of pain and suffering. A participant felt comfort through praying and said, “When I pray, I ask, I give thanks, and I talk, this catharsis diminishes [my anxiety], and I feel much better” (FG5-P8). Religion seemed to offer a belief system that provides a lens through which to understand and cope with the discomfort inherent in painful situations. Establishing a connection with a divine entity evolved into a method of releasing and praising pain, providing a sense of love and care in adversity. Seeking divine intercession and release from earthly expectations is perceived as a supreme act of love and surrender in the face of the unknown.

Spirituality is not limited to the religious sphere. Spirituality takes on a profound meaning even for those not identifying as religious. It emerged as a source of inner peace and connection to aspects beyond the material. A participant showed other aspects of spiritual self-care and mentioned, “Meditation, reading books on spiritual matters, self-help, and a positive attitude have helped me a lot. A change in my view of what death is” (FG10-P4). Participants found in spirituality a path to reflection and serenity, independent of religious affiliation, which is defined as a personal search for meaning and inner well-being. Meditation is also established as a spiritual vehicle in itself, a self-care technique that surpasses religious barriers. Through meditation, individuals found a space for inner dialogue and connection with their thoughts and feelings. Meditation acted as an avenue for emotional release and catharsis, providing a respite from daily concerns. Meditation and mindfulness exercises have also been identified as useful in other PC contexts [23].

Through self-analysis, self-reflection, and self-awareness, professionals deepen their experience, anticipate challenges, and foster emotional balance and resilience. These strategies empower and authenticate, laying a deep foundation for self-care in this demanding work environment. Other researchers point out that self-care itself should not be understood as a practice to alleviate professional burnout but as the cultivation of self-awareness or a high level of consciousness, which helps transform the experience of patients’ suffering, to be realistic and consistent with personal values and vocation, and to develop the spiritual dimension as professionals [19].

3.4. Limitations

Every study has its limitations, and this one is no exception. Most notable is the possibility of “limited generalisability.” We employed convenience sampling, and although the sample was large, it was self-selected. Study participants were those interested in the topic, and that might influence how they perceive their professional quality of life and how they manage and talk about their self-care. Further research is needed to explore the experiences of those who might be reluctant to take part in such studies. Even though we believe it is a strength to consider the PC team as a unit, given the multidisciplinary practice of this type of care, the sample had a particular composition, which may limit the applicability of the results. Specifically, the sample included more women than men, more professionals than volunteers or students, more people from medical and nursing areas, and more people from nonprofit organizations; they also worked in urban geographical locations. Future studies could explore the applicability of the proposed tool and other specific aspects of self-care of each of these groups.

Another limitation of generalizability could be the context. Although this study was conducted in Ecuador, and there is not enough research on the cultural differences in self-care, every country has its own cultural traditions that could influence self-care behaviors [36]. However, research has also shown that the diversity of self-care preferences and values can be studied across heterogeneous ethnicities, cultures, and occupations with a single measure [50]. Thus, our results could also inform other professionals and policymakers to create tailored interventions that accommodate cultural factors and social norms.

As with any qualitative research, certain limitations must also be considered concerning the FG sessions, such as “time constraints.” As the sessions were limited to a maximum of 2 h, specific issues may have yet to be explored in depth. In addition, “group influence” should be acknowledged. The interaction dynamics between FG participants could influence the answers and opinions expressed during the discussions.

Despite the limitations, this research explores the multifaceted nature of self-care and highlights its importance in social and PC. Developing practical approaches requires a holistic perspective that overcomes barriers and promotes practices that support professionals’ physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Fostering self-care encompasses individual strategies, interpersonal relationships, workplace dynamics, and organizational support. Ultimately, self-care affects not only professionals’ quality of life, health, and empowerment [51] but also the quality of care they provide to patients and their families [52].

4. Conclusions

The results of this qualitative research shed light on the nature of the professionals, volunteers, and students who dedicate themselves to providing the highest quality of life for PC patients and their families. However, this noble pursuit is accompanied by its own burdens, resulting in emotional and physical exhaustion. In this context, self-care is a fundamental strategy to tackle these challenges.

The findings highlight the need to go beyond simply recognizing the benefits of self-care and address the underlying structures that hinder its implementation. Effective self-care promotion should consider the challenges and offer adaptable and realistic strategies that can be integrated into professionals’ routines. It also emphasizes that self-care should be individualized and evolve with time and situation.

Changing the socioprofessional culture is essential to embedding self-care as a pillar of sustainable well-being over time. Self-care unfolds as an interconnected network that goes beyond the physical, including personal image maintenance, occasional self-indulgence, mental relaxation, and emotional expression. This complex interplay strengthens resilience and well-being. Socialization with friends and family is an emotional balm that nourishes and strengthens professionals, giving them the resilience to face challenges. This social connection solidifies as a fundamental component of self-care. Building strong peer relationships, seeking guidance from experienced colleagues, and accessing external support networks (friends, family, therapy) are vital.

The spiritual dimension of the self also emphasized how holistic self-care must be. Different activities and strategies nourish the spiritual and emotional dimensions, and the quest for inner calm transcends religious and cultural boundaries to become a universal self-care strategy. Finally, professional development emerges as a less common but enriching self-care strategy. It goes beyond acquiring skills, fostering confidence, competence, and contribution to the field. Ongoing training and professional development also contribute to bolstering self-confidence and overall well-being. There is an organizational responsibility to facilitate self-care; investing in professional development could positively impact self-care.

4.1. Suggestions for Self-Care Planning

Below is a tool to facilitate personalized self-care planning (Table 3). The tool review was conducted using the Delphi methodology [53] to gather and synthesize opinions from a group of experts. The panel initially included two prominent university professors in self-care and two professionals in PC. The process was divided into rounds, during which the tool was provided for comments and suggestions. Suggestions were analyzed and synthesized, with revisions presented in successive rounds until a satisfactory consensus was reached. Finally, the suggestions were integrated into a final version validated by the expert panel. The tool is designed to be completed individually and covers personal and work-related aspects. The importance of setting achievable goals is emphasized rather than setting ambitious and unrealistic goals. It is recommended to start with simple and achievable steps. The SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) methodology is used as a goal-setting guide [54].

| Self-care planning chart for professionals working in the healthcare and social care sectors and in palliative care in the Ecuadorian context. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Why practice self-care? (State in your own words your reasons why self-care is important for you) | ||||

| Step 2: Self-analysis. | Step 3: Identifying barriers | Step 4: Setting goals | Step 5: Review and adjust (Evaluate every 30 days. Adapt and return to Step 3) | |

| Personal self-care | How do I take care of my body (diet, rest, sports…)? | Lack of time. I only have 1 h in the afternoon on Tuesdays and Thursdays. |

|

|

| How do I take care of my mind (resting, feeling good, rewarding, having fun…)? | ||||

| How do I take care of my social world (the spaces where I can be with my family and friends)? | ||||

| How do I take care of myself spiritually (mindfulness, meditation, religion…)? | ||||

| Self-care at work | Who is part of my support system at work and how much time do I invest in them (therapist, supervision groups, meetings with the coordinator, team meetings…)? | |||

| How can I improve my professional competence (training, reading articles, attending congresses, courses…)? | ||||

| How much time do I spend assessing what is happening to me or being aware of how I am doing (giving myself space to see the reactions of my body and mind)? | ||||

| How can I improve the distribution or planning of my work? | ||||

-

Step 1: Why practice self-care?

-

Here, each person could state the importance of self-care to motivate self-care practices.

-

Step 2: Self-analysis.

-

This step promotes self-awareness of self-care activities. Aspects such as the following are explored.

- •

How do I look after my well-being about __________?

- •

How much time do I spend on these activities during the week?

- •

How could I improve my self-care in this area?

-

Step 3: Identifying barriers.

-

The next step is identifying challenges that might prevent you from achieving your goals. These barriers may include a lack of time, work responsibilities, or ingrained habits. Awareness of these barriers will enable you to set realistic goals and plan strategies to overcome them. Questions might include.

- •

What barriers might limit my improvement in self-care?

- •

How can I effectively address these barriers?

-

Step 4: Setting goals.

-

In this step, you are asked to define new self-care goals. It is not necessary to complete all sections; including two elements in the personal area and two in the work area is sufficient. Goals should meet the SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) criteria and will be accompanied by their schedule in the personal agenda.

-

Step 5: Review and adjust.

-

It is important to schedule a review approximately every 30 days. During this process, the following aspects will be evaluated.

- •

Have I achieved my goals?

- •

What difficulties did I encounter?

- •

Were the goals realistic and in line with my needs?

- •

What changes or adjustments are needed to recalibrate my planning?

It is recommended to return to Step 3 to make relevant adjustments and repeat the process if necessary. We hope that this structure facilitates the creation of a personalized and realistic self-care plan, emphasizing adaptability to individual preferences and the ongoing process of review and improvement. Table 3 is an additional tool to follow these steps.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Universitat de les Illes Balears and the Govern de les Illes Balears (grant number: OCDS-CUD2022/04).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the people who participated in the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The transcripts of the focus group used to support the findings of this study have not been made available to protect confidentiality.