General Practice Care in Residential Aged Care Homes: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

The growing population of older adults residing in Australian residential aged care homes (RACHs) is driving an increased demand for general practitioner (GP) involvement to meet their complex healthcare needs. This scoping review sought to synthesise the evidence on general practice care models implemented within RACHs over the past decade (2013–2023), assessing their structure, effectiveness and implications for Australia’s future healthcare strategies. Employing the Joanna Briggs Institute Scoping Review Methodology, the review systematically searched for English-language studies from five major databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINHAL, Scopus, and PsycINFO) and grey literature, focussing on preventive, management and acute care services for RACH residents aged ≥ 65 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged ≥ 50 within comparable healthcare contexts. Following screening, 10 studies were identified, with half conducted in Australia. Models primarily included government or provider-employed GPs and team-based approaches led by registered nurses or nurse practitioners. Despite structural variations, common elements across models were regular GP consultations, co-located services and multidisciplinary partnerships. Three studies reported differing impacts of general practice models on resident health outcomes; provider-based GPs generally reduced unplanned hospital and emergency visits, whereas nurse practitioner–led teams resulted in a slight increase. Both GP-led and team-based models reported broad adoption and acceptance, though cost-effectiveness varied. Despite identifying several promising models, the existing evidence is insufficient for a comprehensive evaluation of their long-term effects on patient health and the broader healthcare system. This underscores the urgent need for further research to develop effective, culturally sensitive and economically sustainable aged care practices, ensuring high-quality care for Australia’s rapidly ageing population.

Summary

- •

What is known about the topic?

- ◦

Australia’s ageing population increasingly relies on residential aged care homes (RACHs), where residents’ complex health needs require comprehensive care from general practitioners (GPs).

- ◦

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Safety and Quality highlighted systemic flaws in RACHs, including issues with coordination, quality and GP compensation in general practice care.

- ◦

This underscores the urgent need for improved general practice care models to meet the evolving needs of the older people.

- •

What this paper adds:

- ◦

This scoping review evaluates diverse general practice care models in Australian RACHs, detailing their structure and effectiveness.

- ◦

Models included both GP and nurse practitioner–led teams, with shared elements like regular consultations and multidisciplinary partnerships. Effectiveness findings were mixed.

- ◦

It identifies gaps in long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness, underscoring the need for further research on sustainable, culturally sensitive care practices.

1. Introduction

The ageing global population has resulted in an increased reliance on residential aged care homes (RACHs, i.e., nursing or care homes). Approximately 190,000 Australians reside in RACHs, an increase of 50% from the previous decade [1]. This rapid demographic shift exposes the complex health needs of RACH residents, who often experience multiple physical, psychological and neurocognitive comorbidities [2–5]. These challenges create a greater demand for primary care services, and RACH residents rely heavily rely on general practitioners (GPs) for comprehensive medical care to address their unique health challenges [6].

Despite the essential role GPs play, the structure and effectiveness of general practice services within RACHs in Australia remain a major concern [7, 8]. RACHs often rely on independent GPs for resident medical care under the prevalent primary care model [9]. The 2021 Australian Royal Commission into Aged Care Safety and Quality identified systemic inadequacies in general practice care in RACHs, including inconsistent care quality, poor coordination and inadequate GP funding [7]. Evidence reinforces these challenges, indicating that GPs working in RACH settings face remuneration discrepancies [10–12], excessive administrative burdens [10–12] and difficulties maintaining continuity of care [11–13]. These factors significantly hinder the delivery of essential medical services to RACH residents.

Given the growing population of older individuals, it is imperative to develop and implement models of general practice care that cater to the distinct needs of RACH residents. Recent recommendations have triggered dialogue on potential care models, highlighting aspects such as telehealth, collaboration with nurse practitioners and enhanced medication reviews [7]. While foundational, evidence on these models [10, 14] would benefit from a contemporary update to account for evolving best practices and the changing needs of the ageing population. This scoping review sought to (1) identify available models of general practice care for individuals residing in RACHs suitable for implementation in Australia, (2) characterise their format and delivery and (3) summarise findings on resident health outcomes and implementation processes to inform future healthcare strategies.

2. Methods

This systematic scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute Scoping Review Methodology [15], guided by a preestablished protocol outlining the review approach [16].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Included evidence described, evaluated or piloted general practice care models within RACHs for full-time residents aged ≥ 65 years or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged ≥ 50 years. General practice care was defined as the ongoing medical services provided by GPs within RACHs, including preventive care, chronic disease management, acute care and collaboration with other health services and RACH staff. Evidence was included from high-income countries with healthcare systems broadly comparable to Australia’s, including those with universal healthcare coverage (e.g., the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and select European nations), and the United States where findings were considered applicable due to relevance to aged care practices despite systemic differences. Eligible evidence included all primary study designs (e.g., reviews, experimental, observational and qualitative) and grey literature (e.g., national government reports) published from January 2013 to August 2023. This date range was selected to reflect significant changes in general practice service design within RACHs over the past decade. Editorials, commentary letters, conference abstracts and non-English language sources were excluded.

2.2. Search Methods and Sources

An initial keyword search in MEDLINE informed the development of a comprehensive search strategy, applied across MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Scopus and PsycINFO (Supporting Table 1), capturing publications up to August 1, 2023. To enhance comprehensiveness, manual reference list checks and grey literature searches were conducted, including sources such as Open Grey and key health organisation websites.

Search terms combined keywords related to general practice (e.g., ‘general practice’ and ‘general practitioner’), target population and settings (e.g., ‘nursing home’, ‘residential aged care’, ‘elderly care’ and ‘assisted living facilities’) and models of care (e.g., ‘health service’, ‘delivery of health care’ and ‘model of care’). Titles, abstracts and resulting full texts were screened by two independent reviewers (KM and MB) using the Covidence platform [17], with discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (JR).

2.3. Data Extraction, Synthesis and Analysis

Data extraction was completed by a primary reviewer (KM) and included study characteristics (e.g., publication date and country), demographics (e.g., participant age, sex and geographic location), features of general practice care (e.g., service type, work pattern, remuneration and collaborative relationships) and outcomes of interest (e.g., resident health-related and implementation processes). A second reviewer (MB) checked the accuracy of all extracted data. Model characteristics were extracted and analysed thematically following review and discussion by the research team. Implementation outcomes were extracted and categorised using Proctor et al.’s [18] implementation outcome framework, which includes constructs such as acceptability, adoption, appropriateness and cost. A narrative synthesis was used to report the findings, with meta-analysis not pursued due to study variability.

3. Results

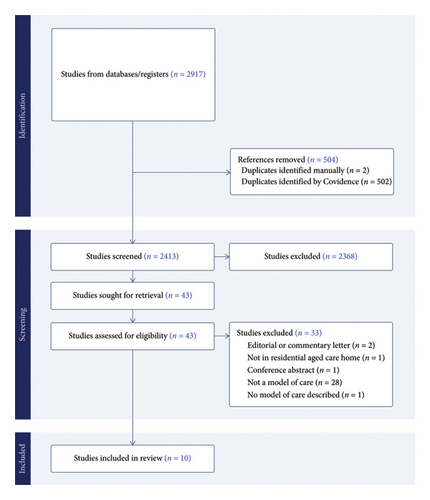

Database searches yielded 2413 original citations. After screening, 43 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with 10 studies included in the final synthesis (Figure 1). No grey literature sources were identified.

3.1. Study Characteristics

Five studies were conducted in Australia [14, 19–22], two in Canada [23, 24] and one each in the UK [25], Denmark [26] and the United States (Table 1) [27]. All were published in peer-reviewed journals. Study design varied; two employed qualitative methods [25, 26], two economic evaluations [21, 23], one randomised controlled trial [19], one cross-sectional study [20] and one mixed-methods investigation [22]. Of the remaining studies, one described a specific model of general practice care [24], another presented a conceptual framework [27] and a third summarised various models implemented in Australian RACHs [14]. Two studies evaluated the same model, focussing on resident health outcomes [19] and cost [21], respectively. Qualitative evidence (i.e., [22, 25, 26]) involved interviews with a total of 54 GPs (∼55%–75% female); however, demographics for other studies’ participants were unspecified.

| Author(s), year, country | Study aims and design | Overview of general practice model | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen et al., 2023, Denmark |

|

One or more GPs serve as designated practitioners to the RACH while retaining their private practice. Residents had the option to enrol with the designated GP but were not required to. The service was publicly funded by the Danish government. No formal guidelines governed collaboration between GPs and care homes. | Acceptability: Both GPs and RACH staff reported that the designated GP model improved communication and clarified roles in care delivery. However, some ongoing communication challenges between GPs and RACH staff were also noted. |

| Haines et al., 2020, Australia |

|

GPs were salaried employees of Bupa Aged Care and each was responsible for approximately 150 residents across 15 RACHs. Depending on facility size and location, some GPs were shared between homes. Each GP was supported by a clinical manager, while care delivery at the resident level was overseen by a designated nurse-in-charge and a nurse team leader supervising care attendant. Although consultations were billed using Medicare items, all Medicare revenue was returned to Bupa, which directly funded the GPs’ salaries. Medicare is Australia’s publicly funded universal healthcare system, which reimburses providers for eligible medical services. | Resident-related: Compared to the pretrial control period, the provider-employed GP was associated with ∼50% fewer unplanned transfers, hospital admissions, GP calls and complaints. However, rates of resident falls, infections and medication errors increased during the intervention period. |

| Lacny et al., 2016, Canada |

|

The nurse practitioner-physician model involved a salaried nurse practitioner employed by the RACH. The nurse works independently, but collaboratively with three in-house GPs who were funded on a fee-for-service basis through Medical Services Insurance (MSI), Nova Scotia’s publicly funded provincial health insurer. The nurse practitioner provided weekday primary care, including diagnosis, treatment and prescribing, and reported to the nursing director. They participated in weekly case discussions with GPs, multidisciplinary team meetings and medication reviews. Advance care planning was shared between the nurse practitioner, nurses and family doctors. |

|

| Marshall et al., 2015, Canada |

|

GPs provided weekly care on designated RACH floors with a target 30-minute on-call response time. The model involved 55 GPs organised into five networks covering 2600 beds. It included regular multidisciplinary team meetings, consultations with advanced care paramedics to minimise ED visits and standardised health status screenings. Clinical care was guided by standing orders and protocols. The model was largely revenue-neutral, aside from on-call coverage costs, and was funded by the Capital District Health Authority, a regional government health authority in Nova Scotia, Canada. | Adoption: The number of GPs providing care per RACH floor decreased following implementation, indicating a consolidation of GP services. |

| Meade et al., 2016, Australia |

|

A general practice team, including GPs and part-time practice nurses, provided care to eight RACHs. GPs conducted twice-weekly rounds as part of routine practice, with additional visits as needed. Resident care responsibilities were shared across the team, with coverage during leave. GPs were available for after-hours care, with practice nurses triaging whether GP input was required. The model was funded through Medicare, with services billed via the MBS. |

|

| Pain et al., 2014, Australia |

|

Three GPs operated from a dedicated weekly clinic space within the RACH, each attending a 2 h weekly shift. After their clinic session, GPs remained on-call until 6 p.m., after which the after-hours GP service assumed coverage. Residents could choose to access their usual GP, a regular GP or the in-house GP for acute care needs. A skilled RACH nurse supported the clinic by reviewing notes and assisting with resident transfers. GPs were remunerated through standard Medicare fee-for-service billing. |

|

| Reed et al., 2015, Australia |

|

This descriptive paper outlines several models of general practice care in the Australian residential aged care home (RACH) context. These include: the continuity model, where GPs continue to care for their long-term patients following admission to a RACH; the specialised GP model, in which GPs focus primarily on aged care and partner with specific facilities, often managing large resident panels; the team-based practice model, where practice nurses or nurse practitioners support or substitute for GPs in delivering care; and the RACH-based model, where facilities collaborate with designated GPs to care for residents who do not have an existing GP. These models are typically funded through Medicare, Australia’s publicly funded healthcare system, with GPs reimbursed via fee-for-service arrangements. | Not assessed. |

| Shield et al., 2014, United States |

|

Using Donabedian’s structure–process–outcome framework, the model outlines how organisational structures within RACHs shape medical staff involvement. Structural dimensions include open versus closed staff models and differing GP employment arrangements. Factors such as physician availability and physical presence influence communication and coordination between medical staff, nursing teams, residents and families. These care processes, in turn, are proposed to impact outcomes such as symptom management and family satisfaction. | Not assessed. |

| Si et al., 2022, Australia |

|

See Haines et al. for full description of the provider-employed GP model. | Cost: The model resulted in increased provider profits, primarily driven by government subsidies and Medicare revenue. Estimated cost impacts per occupied bed day (OBD) included a $9.70 saving for providers, a $19.60 increase in federal government costs and a $3.00 saving for state governments. |

| Warmoth et al., 2022, United Kingdom (UK) |

|

The most common model involved assigning a designated GP to each care home (40% of cases). Other arrangements included one GP serving all local care homes, incorporating care home responsibilities into routine general practice, deploying specialist teams focussed on care for older people and participating in enhanced local service schemes. GP practices reported working with between 0 and 15 care homes. | Acceptability: Among staff in designated GP models, 90% reported positive personal relationships with GPs, and 56% reported efficient working relationships. |

- Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; RACH, residential aged care home; RCT, randomised controlled trial; UK, United Kingdom.

3.2. General Practice Care Models and Integration in RACHs

Reed outlines several Australian RACH general practice care models, including the continuity model, where a resident’s usual GP continues care post-admission; the RACH panel model, where GPs care for multiple residents across nearby RACHs; a model involving GPs with a special interest in aged care providing services; the Longitudinal General Practice Team (LGPT) model, emphasising team-based care with GPs, nurses and other health professionals; and RACH-employed models, where GPs are directly employed by the facility [14].

Other included studies examined a range of models. Three described designated GP arrangements or GPs linked to specific RACHs while maintaining external practice roles [20, 24, 26]. Two evaluated provider-employed GP models funded by aged care providers [19, 21], and two examined nurse practitioner–GP collaborative models reflecting team-based care [22, 23]. One study compared multiple models of general practice care, including designated GP models, shared GP coverage, specialist older people care teams and enhanced local services [25], while another proposed a conceptual framework describing medical staff involvement in RACHs, including GPs [27]. Most studies reported on models implemented across multiple RACHs [14, 19, 21–27]. Settings varied, with some studies focussed on metropolitan areas [23, 24, 26], others on regional and rural RACHs [20, 22] or a mix [19, 21, 25, 27].

3.3. General Practice Components in RACHs

3.3.1. Consultation Type and Frequency

Six studies described onsite general practice services in RACHs [20, 22–24]. Four studies reported regular weekly visits [20, 22–24]. Pain et al. described a model where GPs provided two-hour weekly clinic shifts with dedicated space, supported by a RACH nurse [19]. Three studies reported that residents retained the option to see their regular GP instead of the RACH-based GP [22, 26]. Three models included after-hours care, via on-call GP phone support [24], early evening on-call GP availability [20] and nurse triage before GP involvement [22]. Four models included GPs maintaining external private practice alongside RACH work [20, 22, 23, 26].

3.3.2. GP-to-Resident Ratios

Reported ratios varied widely. Two studies (reporting on one model) indicated a 1:150 GP-to-resident ratio, with GPs shared between facilities based on size and location [19, 21]. Other arrangements included three GPs per RACH [20], 2–3 GPs covering half of residents (1:15 to 1:100 ratio) [23] and one GP per floor (55 GPs across 2600 residents) [24]. One Australian study described GPs managing small resident panels (8–12 residents) to qualify for Medicare incentives [14].

3.3.3. Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Eight studies described collaboration between GPs and nursing staff [14, 19–23, 26, 27]. Five included a nurse practitioner or registered nurse assisting with scheduling, case reviews or triage [14, 19–22]. One described a nurse practitioner supporting GPs during rounds and overseeing diagnostics and medication [23]. Two studies reported nurse–GP collaboration but provided limited detail [26, 27]. Three studies described GPs participating in multidisciplinary meetings or residential medication management reviews [23, 24, 27]. One model also included collaboration with extended care paramedics [24].

Five studies reported fee-for-service GP funding [20, 22–24, 26], while two described salaried GPs employed by the aged care provider [19, 21]. All five Australian studies noted use of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for GP and nurse practitioner services [14, 19–22]. In salaried models, Medicare revenue was retained by the provider [19, 21]. Reed noted GPs managing panels of residents could access Medicare incentives [14]. One Danish study reported GP services funded by the public health system [26], and one Canadian study described a revenue-neutral model with provincial funding for on-call coverage [24].

3.4. Outcomes

3.4.1. Resident-Related Health Outcomes

Three of 10 studies reported on resident health outcomes [19, 20, 23]. Provider-employed GP models were associated with fewer unplanned hospital transfers and emergency department presentations [19, 20]. However, one study also found increases in resident falls, infections and medication errors, potentially reflecting greater on-site care for acutely unwell residents and improved documentation during the study period [19]. One nurse practitioner–GP team model was linked to a modest increase in emergency service use compared to those receiving care solely from a GP [23].

3.4.2. Implementation Outcomes

Reed also briefly described outcome trends associated with Australian general practice models. They noted that despite the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)’s preference for continuity models, where residents retain their existing GP, uptake is limited, with approximately 70% of residents changing GPs upon entering aged care. Reed also reported that while multiple models were in use, evidence on outcomes for LGPTs, panel models and RACH-based models in Australia was not available [14].

Eight studies examined implementation outcomes [19–26]. Four reported on acceptability [19, 22, 25, 26]. One study of a provider-employed model found a slight decrease in RACH staff satisfaction following the introduction of salaried GPs [19]. In contrast, other studies described increased GP satisfaction, reduced administrative burden and improved communication between GPs and RACH staff [22, 25, 26]. One study of a designated GP model noted that staff working in these settings reported more consistent contact and clearer role expectations than staff working with rotating GPs [25].

Three studies reported increased adoption of general practice services following model implementation. These included a rise in total GP consultations, more regular case conferences and reduced reliance on after-hours or emergency care services [20, 22, 24]. For example, one study found compared to the previous care model, where a single GP was responsible for RACH residents, general practice teams (comprising a roster of GPs and dedicated practice nurses) were associated with an increase in total consultations per resident, a shift towards shorter standard consultations (< 20 min), and a reduction in after-hours visits [22]. One study also reported a reduction in the overall number of GPs providing care per facility, suggesting greater continuity in GP assignment [24].

Cost impacts were reported in two studies. A Canadian study found that a nurse practitioner–GP team model led to slightly higher overall costs compared to GP-only care [23]. An economic analysis of the provider-employed GP model reported a saving of $9.70 per occupied bed day (OBD) for the provider, alongside a federal cost increase of $19.60 and a state-level saving of $3.00 per OBD [21]. One study assessed appropriateness; finding team-based GP models were perceived as more financially viable than traditional independent GP arrangements [22].

4. Discussion

This scoping review sought to identify and synthesise models of general practice care in RACHs, with a focus on their structure, integration and potential to inform service delivery in Australia. The evidence base was limited and heterogeneous, with only 10 included studies and considerable variation in study design, care model characteristics and outcomes measures, making cross-study comparison difficult. Our review identified a range of general practice models including government [20, 24, 26] or provider-employed GPs [19, 21] and team-based approaches involving registered nurses or nurse practitioners [22, 23], with differing levels of integration. Notably, only three studies examined resident health-related outcomes, and none included patient-reported outcomes or the perspectives of care recipients, highlighting a substantial gap in evaluating the effectiveness of general practice models from the resident’s point of view. Designated, provider-employed GP models were associated with fewer unplanned hospital transfers and emergency department presentations [19, 20], while one team-based model with nurse practitioners was linked to a modest increase in emergency service use [23]. As healthcare systems adapt to changing demographic needs in Australia and internationally, targeted research is needed to inform effective and scalable models of general practice care that address the complex health needs of older adults and support high-quality care in RACHs.

A common element across care models was the integration of GPs into RACHs, through regular consultations, co-located services and multidisciplinary partnerships between GPs, practice nurses and RACH staff. With Australia’s ageing population and subsequently rising chronic illness rates, collaborative and integrated models of general practice care may be key to managing increasing healthcare complexity, costs and workforce challenges [28]. Approaches which focus on interprofessional collaboration between healthcare professionals aim to improve service access and alleviate workload pressures for GPs [29]. Within RACHs, aspects of care, such as regular consultations and multidisciplinary partnerships, can be mutually beneficial. Pearson et al. [13] found regularly scheduled GP visits improved cooperation between nurses and GPs in RACHs, demonstrating the importance of strong professional relationships for effective care delivery. While these integrated models show promise for improving RACH care quality, our findings suggest recent evidence on their benefits is still emerging.

Eight studies assessed implementation outcomes like acceptability, adoption, appropriateness and cost. Both designated RACH GPs [19, 25, 26] and team-based approaches [22] were well-received by GPs, practice nurses and RACH staff. These findings likely stem from components of care, such as structured schedules for regular GP visits and strong interprofessional partnerships, which have been previously shown to improve GP productivity and satisfaction [30, 31]. Implementing a designated GP [20, 24] or practice nurse [22] prompted increased service adoption, shorter consultations and reduced after-hours care. Despite generally positive feedback from GPs and RACH staff, challenges with role clarity and integration within these models persisted [26]. Co-design strategies involving healthcare professionals may alleviate these issues and enhance implementation. Moreover, since all studies relied on health professional reports, including resident and family perspectives could provide additional valuable insights for more effective implementation.

Studies on the cost-effectiveness of RACH general practice care showed mixed results. While a model with full-time GPs indicated potential healthcare provider savings [21], both it and a NP–GP collaboration model [23] increased government costs due to available subsidies. Financial incentives are argued as crucial for increasing GP involvement in aged care, as inadequate compensation (e.g., direct remuneration, opportunity costs and administrative burdens) remains a major barrier in Australia [12]. Notably, one model (assessed in two studies) employing full-time GPs in provider-run RACHs reduced resident hospitalisations [19] despite increased costs [21]; however, recent correspondence indicates this model is no longer implemented due to sustainability issues [32, 33]. Future research should focus on the balance between initial investment and long-term savings, considering both financial and resident health outcomes, for a more nuanced understanding of the value and sustainability of different general practice care models in RACHs.

4.1. Limitations of Captured Studies and Current Review

Many studies provided incomplete or poorly described details of general practice care components, warranting caution when interpreting findings. Inconsistent reporting and overlapping features made it difficult to classify model types, particularly regarding leadership and integration, which limited the use of fixed typologies and supported a thematic, component-based synthesis approach. Substantial variability in study designs, settings and outcome measures also limits the generalisability of results across aged care contexts. Implementation outcomes such as appropriateness and sustainability were infrequently examined, leaving gaps in understanding the long-term viability of different care models. A key limitation was the lack of studies capturing resident perspective or patient-reported outcomes, which limits insight into how care models affect resident experiences and perceived quality of care. Additionally, there is limited evidence on how existing models address the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and residents from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, underscoring the need for more inclusive and culturally responsive research.

4.2. Priorities for Clinical Practice and Future Research in Australia

This review identifies a number of practical and research priorities to guide the delivery and evaluation of general practice care in RACHs. While models varied in structure and integration, those involving regular GP contact, provider-based employment and collaboration with nursing staff were commonly associated with improved care processes and provider satisfaction. Future research may consider exploring models that embed GPs within aged care teams while remaining flexible to local context. Potential areas for development include co-located consultation spaces, scheduled GP visits and systems that support continuity of care. Recent policy discussions, including those led by the RACGP in response to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, have outlined strategies to support these improvements [34]. These include enhancing clinical infrastructure in RACHs, revising MBS items to enable more proactive care and strengthening GP training in aged care. Considering these enablers in the design of future approaches, while ensuring responsiveness to resident preferences, may help support both care quality and system sustainability.

Future studies would benefit from including outcome measures that capture resident experiences (e.g., satisfaction, perceived continuity of care and medication management) and broader system impacts (e.g., unplanned hospital transfers) to better assess the impact of general practice models. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes and the perspectives of residents and families, including those from diverse populations, may help ensure models are responsive to those receiving care. Implementation-focussed research assessing appropriateness, feasibility and long-term impacts could further inform the development of sustainable and contextually relevant models of care in RACHs.

5. Conclusion

This review highlights the important role of general practice in delivering comprehensive care in RACHs, identifying several model types with common elements: regular GP consultations, co-located services and multidisciplinary partnerships. While only based on three studies, findings suggest provider-employed GP models may reduce unplanned hospital transfers, offering preliminary support for this approach. Despite emerging evidence of benefit, the limited scope and variability of existing studies underline the need for further research to assess the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of general practice models in aged care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Foundation and the HCF Research Foundation (grant number HCF2022-33).

Supporting Information

Supporting Table 1: search terms for MEDLINE database.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.