Introducing a Computerized Care-Pathways System for Older Adults in Home-Care Settings

Abstract

Introducing computerized care pathways for older adults living at home may be a promising way to improve the clinical dimension of integrated care. Evidence on how to implement them in various home-care contexts is, however, sparse. A prospective, comparative multiple case study with nested analysis units was conducted across three home-care settings. Participants included managers, healthcare professionals, and home-care clients. We used a variety of frameworks and both qualitative and quantitative methods to understand the implementation process. The implementation research logic model (IRLM) presents links among determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and outcomes. Twelve barriers and 35 facilitators were similarly perceived, and 40 strategies were commonly adopted during implementation. After 12 months, OCCI implementation was feasible, appropriate, and acceptable at moderate-to-high levels. They were delivered with a moderate level of fidelity, but the level of penetration after 24 months was high. Participants perceived the OCCIs as supporting a holistic approach, good relationships, clinical decision-making, information sharing, and interprofessional coordination, but not as much productivity and efficiency. Home-care clients had a high level of satisfaction with health care and services. They were satisfied about their involvement in decision-making and with computer use by professionals. We identified four causal pathways: engaging interest holders in a partnership model throughout the study; providing an information system that supports clinical processes; building a conducive environment with deliberate efforts to increase buy-in and engagement; facilitating capacity and relationship building to increase adoption; and embedding the OCCIs in usual practice. The results illustrate how a real understanding of contexts was important to elucidate the mechanisms at work during this study. Adapting the innovation to achieve a better fit between it and the clinical contexts was fundamental. Positive outcomes relied on time, appropriated resources, and a continual, iterative process corresponding to “Make It Happen.”

1. Introduction

Over the past 20 years, the province of Quebec, Canada, has been faced with a rapid increase in its aging population and the proportion of older adults experiencing complex interrelated health and social needs that threaten their ability to manage their everyday life [1–3]. Because of their needs, they require a system in favor of integrated care (IC), which facilitates prompt access to community supports, social services, and health care, while eliminating delays, redundant assessments, inadequate information transfer, and inappropriate resource utilization [4–7]. IC can be defined as methods and models on the funding, administrative, organizational, service delivery, and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment, and collaboration within and between the healthcare system (on the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels) and social services with the aim of improving quality of care, consumer satisfaction, and system efficacy for patients with complex, long-standing problems that cut across multiple services, providers, and settings [8, 9]. In the last 25 years, numerous models for organizing IC for older people or people with chronic conditions have been developed and used in different parts of the world [10–13]. However, they greatly varied due to their application in contexts differing in eligibility criteria, levels, domains, types of integration, and finance mechanisms [10, 14–17]. In fact, no one IC model seems best suited to all contexts, settings, and circumstances [14, 18]. Their evaluation studies were also heterogeneous in methodology, and assessments of effectiveness remained mixed. For now, the evidence suggests that IC contributes to better outcomes such as improvement in quality of life, well-being, patient satisfaction, caregiver burden, and resource utilization such as increased access, reduced hospital or emergency admission, and lengths of hospital stay, but the evidence regarding other outcomes is unclear [10–13, 19–22].

Even though there are many models and studies on the topic, it seems that the success of IC systems depends on the ability of all local interest holders to adapt to their new roles and adopt management and clinical tools appropriate to their new tasks. Several factors are frequently reported to influence the spread and scale-up of IC models. They include a change of culture with clinical and management leadership, regulation aligned with services provided across the continuum of care, adequate funding, dedicated time and resources, information and communication technology (ICT) to facilitate communication, physicians’ and healthcare providers’ engagement, effective communication strategies, feedback loops, and a continuous monitoring system [19, 20, 23–25].

Many authors also point out that the patient’s perspective and quality of care should be at the heart of any discussion about IC [13, 14]. Patient-centered care considers the viewpoint of the client by ensuring that services are well coordinated around their needs. Full and accurate information about a patient’s needs and care must be available throughout the care journey to everyone involved, including the patient themselves, using patient portals, and providing them online access to their electronic health records (HERs) [26–28]. This information should be accessible from anywhere in the health system. Nevertheless, even though we possess extensive evidence regarding the factors that facilitate the implementation of IC, we still need a deeper comprehension of their working mechanisms, ideally supported by implementation theories [19, 29].

In Quebec, one ministry already administers all social and healthcare services. Following the positive impacts highlighted by IC projects carried out in our province in the 2000s [6, 30], service integration has since been the central theme of the actions taken by our system to ensure that older adults will remain at home for as long as possible with well-coordinated primary care, health-related services, and support from home care and community-based services (HCBSs) [6, 30–34]. The priority was given to planned and formal coordination at the legislative, administrative, organizational, and clinical levels [33], and components such as local mechanisms for coordination with a single entry point, multidisciplinary teams, comprehensive assessments with care plans introduced in a health information system (HIS), patient empowerment, and case management were gradually implemented for community-dwelling frail older people [15, 32]. However, although IC has gradually been embedded in our health and social care system, some gaps associated with needs assessment, planning, and service coordination have remained [31, 34–36]. In fact, providers have considered that government policy and mergers have strongly influenced the implementation of organizational and functional dimensions of integration to the detriment of clinical integration [35, 37, 38]. According to these authors, healthcare providers considered that the system was focused on providing services rather than needs and that shared decision-making with clients and caregivers was difficult to implement, although person-centered care was a central principle promoted by their organizations. They also suggested that additional efforts were needed to improve the HIS named the RSIPA (2009 version; French acronym for “Réseau de services intégrés pour les personnes adultes”) and its interoperability. Indeed, task-oriented service delivery frequently overlooked the need for psychosocial services [39, 40]. Similar to other systems, we have also observed some issues related to fall prevention, nutritional needs, and the identification of at-risk older adults [41, 42].

Given these challenges, it has become important to find new ways of working to better assess, support the needs, and improve our IC model for home-care clients. Integrated care pathways (ICPs) have been introduced in many settings as a strategy to reduce variations in care by improving adherence to recommended best-care practices [43, 44]. ICPs are also a way to improve coordination of care, multidisciplinary and professional–patient communication, and patient satisfaction [45–47]. Minimally, ICPs are complex interventions based on an assessment with a care planning process that is supported by multidisciplinary teamwork. They structure care around individual needs, combine evidence-based key interventions, and provide feedback on the current care process, like many interventions based on assessment instruments used in home care [48, 49]. However, ICPs are more than that as they emphasize the follow-up of patient-focused care, which includes the monitoring and evaluation of variances and outcomes in real-time [50]. Variance analysis enables the identification of discrepancies between anticipated and actual care, thereby facilitating adjustments to the plan or services to ensure they adequately meet needs [51]. Variance data can enhance systems and clinical practices and aid in the planning of health service delivery [52]. ICPs have been used for over 30 years to improve the quality of care and maximize care outcomes for specific groups of users [43, 53]. However, they are more common in acute care sectors or for unique clinical situations (e.g., stroke) rather than for clientele with complex interrelated health and social needs requiring the expertise of multiple care providers and services [54–57]. In a study comparing various care processes with and without care pathways in hospitals, they found that in around 75% of the cases, a care pathway led to better organized care processes [43]. However, the literature lacks detailed information about the implementation and evaluation of computerized ICPs or similar interventions for frail older adults with multiple needs who are living at home in the context of IC [57, 58].

For now, in common with IC or comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), we know that ICP implementation requires robust ICT with combined strategies to address potential barriers. Studies also showed that adequate staffing, professional collaboration, and continuous training are important facilitators to their implementation [49, 59]. One important feature is interoperability between the various ICT systems that necessitate large investments into HER [59]. A review of 77 studies on IC for older people in different settings found that no more than 36 of them were ICT-based IC models and that only 33% of them used HER [21]. Some digital solutions that support communication and data sharing among professionals, such as PROCare4life, tested in six European countries, seem promising but still need significant refinements before being embedded in their health and social care [60].

For professionals, ICPs may also be burdensome because of added documentation, compliance requirements, and communication among multidisciplinary teams [59]. In return, well-designed interoperable, HER systems with predictive algorithms may reduce omissions, enhance care coordination, and enable professionals to intervene much earlier [59, 61]. Other professionals also feel that ICPs may inhibit their judgment in practice and damage their autonomy [62]. But using real-time data from patients and advanced digital analytics may support the shared decision-making process and help find a balance between standardization and personalization through close monitoring of personalized delivery processes and real-time feedback [59, 63].

All these considerations have been appraised when developing ICPs specifically designed to better address the complex chronic needs of frail older adults living in the community. Referred to as Outils de Cheminement Clinique Informatisés (OCCIs for computerized care-pathway systems), they are a promising, innovative way to improve the clinical dimension of service integration [64, 65]. The OCCIs are an extension to a prior research program on IC programs for older adults with disabilities living in a community-based IC network (program on research for integrating services for the maintenance of autonomy [PRISMA]) [6, 66] and diagnoses provincial needs [64]. They consist of a standardized comprehensive assessment and structured multidisciplinary care plans, made with the older person’s or a family member’s input and expectations. These are part of a core decision-support system that tells you what to do in a given clinical situation and then analyzes variations to help you find the best solution for the needs of adults living in the community. They were developed to facilitate communication and support clinical and management processes in home-care services and across the continuum of services. Based on Quebec’s “healthy aging” model—which takes account of all the intervention factors and strategies intended to maintain or improve the health of older persons [67]—the OCCIs included relevant overlapping concepts such as person-centered care, reablement, and proactive care with identification of at-risk older adults.

When the OCCIs were being developed, their inclusion in a HIS was quickly recognized as a key component of their successful use. To this end, the information technology branch of the ministry (DGTI/MSSS) (Direction Générale des Technologies de l’Information du MSSS) integrated them into their computerized clinical and management solution referred to as the RSIPA [68]. This process led to an improved solution—the RSIPA (2016 version). Subsequently, the provincial Ministry of Health and Social Services (MSSS) (French acronym for Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux) decided to support a multisite project to test and refine the RSIPA and to determine whether the OCCIs could be a solution to establishing efficient practices. However, the OCCIs are based on components like comprehensive assessment, person-centered care, and e-health technology, for which several known factors could act as obstacles and hinder their implementation [45, 69–71]. Introducing them into home-care standard practices is likely to introduce several changes that could affect clients or their caregivers, professionals, and managers. It is therefore imperative to evaluate these potential changes since many regions in the province have expressed a strong interest in using them.

According to Greenhalgh et al. [72], the OCCIs constitute an innovation in the organization of health services as they bring new clinical, organizational, and technological practices. By measuring the three main stages of OCCI implementation—preimplementation, implementation, and innovation sustainment—we can better inform implementation strategies and explain implementation outcomes, as well as possibly increase their transferability. So, the main goal was to look at how the OCCIs could be used in the right way in the real world, like in home care settings, in providing insight into determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and outcomes of the implementation processes. We also explored whether rolling out the OCCIs was an effective way to support managers and professionals in their work to improve the response to the needs of older adults in the context of IC. In this way, we investigated both services (e.g., quality of clinical decision-making) and client outcomes (e.g., satisfaction).

This multiple case study with mixed methods aimed at conducting a process evaluation to understand what worked, how, and why in OCCI implementation across the three designated home-care settings. The implementation research logic model (IRLM) was used to present and link determinants, strategies, and outcomes in identifying plausible causal pathways [73]. These aims responded to the concerns expressed by the decision-makers and managers associated with this project. Moreover, the findings provided a firmer foundation for future implementation throughout the province of Quebec.

- 1.

How do determinants facilitate or impede OCCI implementation?

- 2.

What strategies are applied to promote OCCI implementation?

- 3.

What are the implementation outcomes?

- 4.

How are OCCI outcomes perceived by managers and healthcare professionals?

- 5.

How are OCCI outcomes perceived by the clients of home-care services?

- 6.

What are the links and plausible causal pathways between determinants, strategies, and outcomes?

2. Methods

2.1. The Quebec Health and Social Service System

Since 2015, the province of Quebec has been divided into 16 regions with 22 functional structures. They include 13 CISSSs (Health and Social Service Centres; French acronym: CISSS for Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux) and 9 CIUSSSs (Integrated University Health and Social Service Centres; French acronym: CIUSSS for Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux) to ensure accessibility, continuity, and quality of services for people in their territory (Act respecting Health Services and Social Services (chapter S-4.2, s. 99, available at https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/home). Each center had five types of services: CH: hospital center; CHSLD: residential and long-term care center; CLSC: local community service center; CPEJ: child and youth protection center; and CR: rehabilitation center. The 22 CISSSs/CIUSSSs report directly to the MSSS and had to develop strategic partnerships with community and private organizations in their new territories. They are responsible for organizing, managing, and delivering all public health and social care to their local populations. Each center provides home-care services for people with disabilities and older adults through their local community health and social centers (French acronym: CLSC for Centres locaux de santé communautaires). Some services are also available to their family members and caregivers. After a common standardized assessment, clients may receive professional services (such as from nurses, social workers, occupational or respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, and dieticians) and nonprofessional services (such as support for activities of daily living [ADLs]). Community and private organizations in the same territory provide services such as meal preparation, meals-on-wheels, housekeeping, and transportation. Care and services are coordinated by case managers or a main provider, depending on the clinical complexity. The process of client assessment and care planning is supported by different tools included in the secure web platform (RSIPA), which has been available online for health professionals since 2005 [74, 75].

2.2. Description of the Innovation

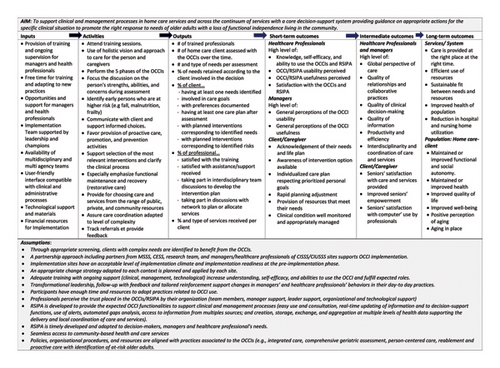

We provide a brief description of the OCCIs here. They consist of five clinical phases [64, 65, 68], and more details are provided in the Additional file 1 using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist [76]. The various components are summarized under the Logic Model of the OCCIs, which graphically describes the underlying assumptions, planned work, and intended results of this innovation [77] (see Figure 1). Basically, the first phase is a needs assessment that documents the source and causes of the client’s needs, what is most important for them and their caregivers, and the identification of risk factors that must be identified to reduce disabilities. Supported by algorithms, the second phase depicts the concise clinical situation and supports the shared decision-making process in which the client’s priority needs and the goals to be reached in care-plan development and implementation are determined. In the third phase, considering the identified goals, the system proposes interventions based on evidence-based practices. Thus, in agreement with the recipient, the expected pathway appropriate for the clinical situation and expectations of the client and caregivers is produced in a personalized care plan. At the fourth phase, the completed pathway supports the documentation of coordination and service delivery. The final phase involves identifying and analyzing variances or gaps, along with the reasons behind them, to support the necessary plan review and adjustment. At the beginning of this study, the computerization of Phases 4 and 5 had not been completely finalized in the system. During the implementation of OCCI, these phases will continue to be developed using a participatory design (PD) that includes end users and people with an interest [68, 78].

2.3. Study Design

The study design consisted of a comparative multiple case study with nested analysis units. It uses both qualitative and quantitative methods and a prospective evaluation approach in three home-care settings [79, 80]. A comparative case study is useful for examining causality, particularly when understanding the context is crucial for assessing the intervention’s success or failure [81]. This methodology allows for using multiple data sources and methods in order to consider a multiplicity of perspectives, levels of decision-making, and analysis over the time frame of the intervention, as well as to capture complex relationships among contexts, processes, and outcomes of the intervention [79]. Three CISSSs/CIUSSSs (Sites A, B, and C anonymized), from different regions in Quebec, were selected because of their successful collaborations and their potential to respond quickly to the technological changes associated with this project. Each setting was a distinct case, and we use the term case and site interchangeably. The number of cases was limited to three to ensure that each case was studied in enough detail, while considering the short time frame and the available financial resources. Overall, each site delivers home care within the existing governance of the Quebec healthcare system and has the same structure as several public establishments. The cases were purposely selected using theoretical replication logic. They present contrasting specificities in terms of the number and size of the organization given their territorial and population characteristics and modes of delivery (see Table 1). The OCCI implementation, as observed in each case, was the phenomenon under study. It took place over a 24-month period and included three phases: preimplementation (i.e., teaming, initiation, and planning—about 3 months); during implementation (i.e., execution with monitoring—0 to 12 months); and postimplementation (i.e., end of the implementation with outcomes and sustainment—12 to 24 months). The design is consistent with the IRLM, which guides our in-depth investigation of the links among determinants, strategies, and outcomes in order to identify plausible causal pathways over time [73]. Lastly, a monitoring committee—including some representatives of the DGTI/MSSS, the Sherbrooke health expertise center (French acronym: CESS for Centre d’Expertise en Santé de Sherbrooke), the research team, project managers, and some healthcare professionals from the selected sites—was also established for the duration of the study.

| Cases—CISSSs/CIUSSS | Site A | Site B | Site C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of area | Semi-urban | Semirural | Highly urban |

| Population | 213,000 | 247,049 | 225,698 |

| Speaking | Mainly French | Mainly French | Mainly English |

| % aged 65 or older | 14% | 17% | 16% |

| Territory | 1346 km2 | 4756 km2 | 132 km2 |

| Living in rural area | 13% | 33% | — |

| # of employees | 2681 | 4330 | 2202 |

| # of hospital | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| # of CHSLD | 3 | 13 | 1 |

| # of CLSC | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Inhabitant density | 158/km2 | 53/km2 | 1710/km2 |

| Implementation level of RSIPA 2009 before the study | 73% | 84% | 75% |

| Who do the first OEMC | Rapid assessment team | Most often social workers or occupational therapists | Most often social workers or nurses |

| Service with the longest waiting list | Nutrition | Occupational therapist and physiotherapist | Occupational therapist |

2.4. Analysis Units and Participants

The research team initially contacted, by telephone, the three CISSSs, who agreed to participate in this study. We provided them with preliminary information about the study and invited them to share details about the served population and structural characteristics of their institutions. Level 1 consisted of employees in management roles, such as high- and mid-level leaders or those supporting the implementation (referred to as managers herein). Level 2 included healthcare professionals (i.e., nurses, social workers, occupational and respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, and dieticians) likely to use the OCCIs. We invited everyone involved in the study’s implementation to participate. The number of managers and professionals varied per site, depending on the method of data collection and the scope of the planned project deployment at each site. Before each qualitative data collection, participants first received information on the study procedure, data protection, and anonymization, and they provided informed consent prior to their participation in the study. When we used self-report questionnaires, potentially eligible participants received an initial email from management alerting them to the upcoming questionnaire. They then received an individual email outlining the study’s objectives, instructions, and links to the online questionnaire. Completion of the questionnaire via the platform constituted their consent to participate in the study. We sent a reminder 2 weeks later to those who did not complete the questionnaires. We offered them an extension period. Level 3 consisted of a sample of home-care clients who had been assessed with the OCCIs and exposed to computer use during their assessment at home. We randomly selected 10 elders, family members, or caregivers per site to represent different levels of functional autonomy based on Iso-SMAF profiles. They had to speak and understand French. Caregivers were considered in situations in which home-care clients were unable to respond to the interview or in situations in which they wanted to participate with the elder. The list of identified persons was provided by professionals at each site who obtained clients’ consent to be contacted by a research team member. Written informed consents were obtained before the interviews, which were held in client homes. All measures to ensure confidentiality and establish a relationship of trust with clients and their families who agreed to participate were taken. We ensured confidentiality by replacing nominal information with codes. An institutional convenience process was obtained for each site, and the study was approved by the CISSS Chaudière-Appalaches Research Ethics Board (MP-23-2016-343, MP-2016-016) in May 2016. This board acts as the main evaluator for the multicenter research project. The decision of this main board also applied to the other two centers.

2.5. Overall Data Collection Process and Analysis

We first present the general process of data collection and analysis. Then, the specific methodological considerations associated with each research question are detailed in the next section, 2.6. Table 2 presents a summary of the data collection methods according to each research question and implementation phase (see the end of Section 2.5). To guide the data collection and analysis process, we applied different theoretical frameworks or models according to each research question. Data collection included quantitative and qualitative methods with different sources to inform the implementation process and outcomes over the study. We carried out the collection in the same manner at each site, but sequentially, one site after the other, a few months apart. The study started in 2016 at one site and then at the beginning of 2017 at other sites. The implementation process at the three sites finished at the end of 2017. We received the final databases containing the OCCIs data completed during the study for all the home-care clients from the baseline to the postimplementation phase (24 months) in 2019. These data were encrypted and stored on the network of the Research Centre on Aging of the CIUSSS Estrie—CHUS. Nominative information was coded to preserve anonymity.

| Data collection methods | Concepts and framework, model, or taxonomy | RQ |

|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation phase (≈3 months before implementation) | ||

|

|

#1 |

|

|

#1 |

|

|

#1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

#1 |

| During implementation (0–12 months) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| End of implementation phase (12–24 months) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each data collection method was designed based on the literature review, adapted to the target audience (managers (M) and healthcare professionals (P)), and pilot tested. The quantitative and qualitative data collected from the various sources were first processed and analyzed given equal weightage, then merged in the interpretation stage (when necessary) and linked to each research question after each phase. For each question, a summary of all data sources with three separate descriptive case study reports was built.

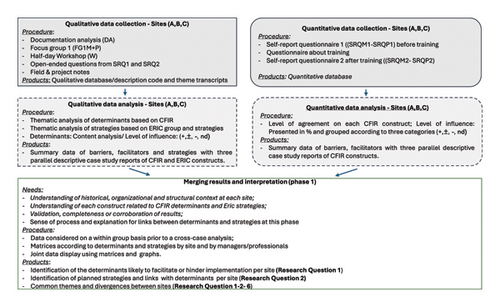

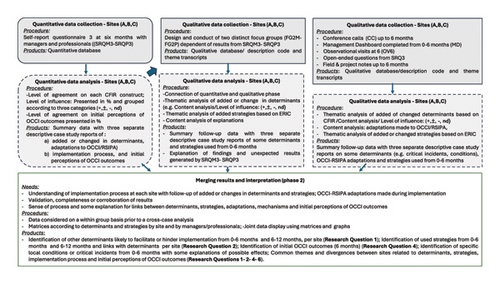

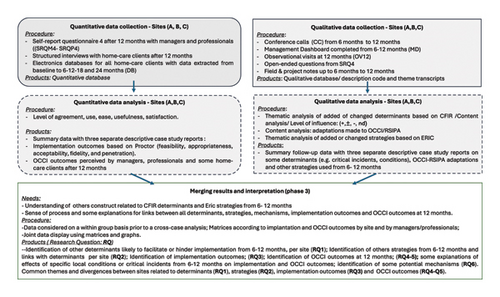

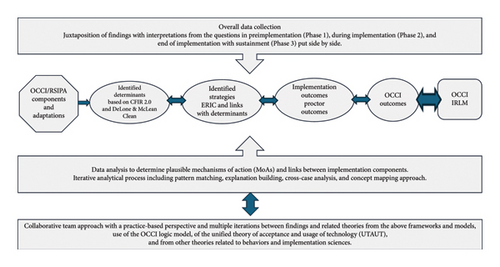

Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 schematize and describe the analysis process, which allowed us to answer each research question within each phase (see Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 after Table 2, before Section 2.6). We developed a case study database using Microsoft Excel to manage and organize all data collection and analysis [79]. Concerning quantitative methods, they included Likert-scale questionnaires used in internet Lime surveys or in-person interviews distributed at various times during the study. We also used the data coming from an anonymized electronic database containing the OCCIs data completed during the study for all the home care clients. To develop the questionnaires, we chose questions from validated instruments that have been shortened due to the limited time available for participants to respond and to minimize respondent fatigue (see Table 2). Questions were prioritized based on relevancy to cover selected frameworks or models, and the wording was adapted specifically to the context of OCCI implementation. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze quantitative data using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. Responses to each question from structured questionnaires were grouped and presented in percentages according to their constructs and the scale used (e.g., level of agreement, frequency, and so on). Bivariate analyses were performed, including some nonparametric statistical tests because of the small number of participants at two sites. Specifically, as an example, Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the relationship between two categorical variables, while the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for continuous variables. We tested the differences in perceptions between each site. We analyzed the open-ended questions and optional comments at the end of the questionnaires along with all the qualitative data. We presented the quantitative results as tables with their respective themes and constructs across sites, considering the type of participants (managers or professionals). We also graphically displayed the results in various colors to facilitate the analysis and understanding both within and between sites.

Qualitative methods included document analysis, focus groups, interactive workshops, conference calls, management dashboards, observational visits, and open-ended questions. All the conversations were audiotaped, and they were transcribed verbatim by the experienced research coordinator. Next, we conducted a hybrid process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis, drawing inspiration from Braun and Clarke [89]. We first developed a code manual that included detailed definitions according to each framework or model selected and adapted to the specific context of the study. A senior research assistant experienced in qualitative studies (CC) conducted the qualitative data analysis by reading each transcript and the field notes for familiarity with the data. The assistant developed preliminary codes and subthemes manually using both inductive and deductive approaches (open coding and coding of theoretical constructs). Major themes were then mapped to the selected framework or model. The codes that did not fit in a framework were evaluated and reconsidered. A research team member (ND) independently reviewed a random selection of about one-third of the transcripts. The research team discussed discordant coding until they reached a consensus (CC, AN, ND, and NDC). Consistent with Braun and Clarke [89], the inclusion was based on the extent to which the theme contributed to expanding knowledge to answer research questions, not just occurrences within the data. The first member sometimes checked the findings and interpretations with the study participants. Systematic and iterative reading and coding allowed for findings focused on research questions. To support the cross-case analyses, the data were organized in Word and Excel documents using matrices broken down according to the specific constructs associated with each research question, the targeted adopter type when available (managers/professionals), and by site [90]. Representatives’ quotes for each of them were manually selected. Peer debriefing and reflexive writing throughout the coding process were carried out. A reflexive journal was used to keep track of emerging impressions of what the data meant, how the data related to each other, or to follow the decision trail. Regular research meetings were held to discuss codes that did not seem to fit into the main themes, discrepant data, or inadequacies in the initial coding.

Finally, depending on the research question, we used a side-by-side display that juxtaposes quantitative results with related qualitative results and evaluated convergence, complementarity, and expansion to support integration, understanding, and interpretation of both types of data [91].

2.6. The Specific Methodological Considerations Associated With Each Research Question

- •

Research Question 1: How do determinants facilitate or impede OCCI implementation?

- •

Research Question 2: What strategies are applied to promote OCCI implementation?

-

We assessed determinants and strategies both before and during the implementation process (0–6 months; 6–12 months). One method for comprehending determinants is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR 1.0) [95]. Commonly referred to as “barriers” and “facilitators,” determinants may also be utilized to direct the choice of strategies to get past obstacles and make the subsequent implementation easier [96]. To capture the determinants, we started this study using the original CFIR 1.0 [95]. But by the time our analyses and preliminary manuscripts were finished, the updated CFIR version 2.0 was published, which was based on user feedback and more recent literature [97]. We decided to review our data with the CFIR 2.0 as it clarified and added several concepts. Apart from the intervention characteristics domain, which is now known as the innovation domain, all five of the updated CFIR’s domains have additional constructs and subconstructs that were useful to better describe our data. The use of “recipients” rather than “patients,” and “deliverers” for all those involved in providing the innovation were among the few changes made to each domain and construct overall. It now includes five domains with 48 constructs and 19 subconstructs: (1) Innovation domain refers to the perceptions of OCCI features, including their clinical and technological contents (RSIPA); (2) outer setting domain is the feature of external context in which our CISSS/CIUSSS are embedded, i.e., the healthcare and social services system with its policies, including the MSSS; (3) inner setting domain refers to the characteristics of each setting named CISSS that houses the CLSCs in which the OCCIs were implemented; (4) individuals domain considers the different roles and characteristics of individuals such as managers and healthcare professionals; and (5) implementation process domain relates to the implementation strategies, including adaptations made during OCCI implementation (https://cfirguide.org/). Adaptations are any deliberate change made to the design or delivery of the OCCIs/RSIPA with the goal of improving fit or effectiveness or in reaction to unanticipated challenges arising in each context [98].

-

Implementation strategies can be defined as methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice. The strategies outlined by each site were mapped to the Expert Recommendations for Implementation of Change (ERIC), which is a published compilation of 73 implementation strategy terms and definitions [99].

-

We used six methods of data collection in the preimplementation phase (see Table 2). (1) Documentation analysis permitted gathering information about the served population and the structural characteristics of their institutions. (2) Then, a focus group was conducted in-person by researchers and coordinators with key people in management roles or directly involved in planning or carrying out the future implementation at each site. The discussions focused on their current governance structures, project management methods (e.g., Lean methodology), organizational processes, clinical practices, and the type of usual support (clinical and technological) provided to clinical teams. (3) Shortly afterward, a computerized self-reported questionnaire (SRQ1) adapted to the target audience (managers (M) and healthcare professionals (P)) was sent to all potentially eligible participants. The questions aimed at finding out how the individual participants perceived their current work contexts; their practices, such as knowledge about assessment, planning, shared decision-making, patient-focused care, reablement, and prior interdisciplinary and intersectoral practices; and the tools used (e.g., OEMC, PSIAS) before becoming familiar with the OCCIs. (4) In a subsequent step, we organized a half-day workshop with the individuals directly involved in planning or carrying out the implementation at each site. One investigator conducted the focus group, supported by a coinvestigator who probed questions if necessary. The research coordinator recalled questions as needed and kept track of time. After a more detailed presentation of the OCCIs, we asked interest holders about initial perceptions of OCCI characteristics, in terms of how they could be of added value for them, healthcare professionals, and home-care clients. Then, we discussed issues related to each current context and further OCCI implementation. Based on all this information, they presented their ideas on the most promising strategies for their contexts and considered the maximum study duration. (5) Subsequently, a 2-day training session with formalized tools and methods was developed by the research team and the CESS according to the needs of all the sites. This team delivered and validated the training at the first site before offering it at the other sites. Each training session concluded with an assessment of satisfaction with its content, trainers, locations, organization, and learning. (6) Lastly, around 1 month after training, another self-reported questionnaire (SRQ2) was sent to each audience to document their knowledge and perceptions of the OCCIs, as well as their perceptions about their ability to use them.

-

During the implementation phase (from 0 to 12 months), five methods of data collection were used: (1) First, 6 months after implementation, a computerized self-reported questionnaire, SRQ3, tailored to each participant group, was fulfilled to cover mainly CFIR 2.0 determinants associated with the implementation process domain and some others about the relative advantage of the OCCIs. Since the OCCIs are integrated into an information system (IS), specific determinants, such as experience of users, system reliability, response time, information quality, and service quality, were considered [92]. (2) Consecutively, two distinct focus groups were conducted by two researchers and the research coordinator with participants directly involved in planning or carrying out the implementation and considered as having the most experience with the OCCIs. We began by presenting the results from the self-reported SRQ3M or SRQ3P questionnaire. This allowed us to start the discussion to determine whether they modified or added some strategies, if some events were crucial for local appropriation of the OCCIs, and what factors could explain the initial OCCI outcomes. (3) During the implementation process, a management dashboard was also completed by each site to report the difficulties encountered with the solutions adopted. (4) In parallel, regular conference calls were held between all partners, and a decision log that compiled all challenges and decisions regarding implementation was completed. (5) Two periods of field observation were carried out at 6 and 12 months to identify the conditions of OCCI use at each site. The observations were based on a template with specific indicators (e.g., availability or layout of workstations or technical information).

-

Concerning the analysis of determinants assessed with questionnaires, responses to each question were first grouped and presented in percentages according to three categories: disagree (strongly disagree, disagree), neutral (neither agree nor disagree), and agree (agree, strongly agree). To simplify the presentation of results, facilitate integration with qualitative data, and preserve the anonymity of sites and participant groups, each exact percentage was replaced with a plus sign (potentially positive effect on implementation), a minus sign (potentially negative effect), a plus-or-minus sign (potentially mixed effect), or nd (no data or question not asked of a category of participants). The item was considered as having a potentially positive effect (+) when more than 50% of participants (M = managers) or (P = healthcare professionals) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. For example, under the Innovative relative advantage, if the statement “I recognize the advantage of using the OCCIs daily in my practice” gets 80% of agreement by managers, the percentage in the M column was replaced with +. The item was considered as having a potentially negative effect (−) when more than 50% of participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. Lastly, the item was considered as having a potentially mixed effect (±) when more than 50% of participants were neutral (neither agreed nor disagreed) about the statement or when none of the percentages were > 50%.

-

Regarding determinants assessed with qualitative methods, each code was reviewed to indicate whether it represented a potentially positive, negative, or uncertain/neutral influence represented by signs (+, −, or ±). During coding, the research coordinator periodically checked the interpretation with other members to ensure consistency of interpretation and guard against bias.

-

Finally, to facilitate linkages between all determinants and strategies, we confirmed links with the CFIR ERIC matching tool [100]. It contains 73 techniques organized into nine clusters available in an Excel-based matching tool, which allows users to input implementation barriers, defined by the CFIR, to receive recommendations about expert-recommended implementation strategies (ERICs) that might address these barriers (https://cfirguide.org/choosing-strategies/). See Figures 2 and 3 schematizing the process of data collection, analysis, merging results, and interpretation during these implementation phases.

- •

Research Question 3- What are the implementation outcomes?

-

Evaluation of implementation outcomes was based on the Proctor Implementation Outcomes Framework [101, 102]. They can be defined as the effects of intentional and purposeful actions to implement new practices or services and serve as indicators or markers of the implementation process and success. Furthermore, they are seen as essential conditions for achieving later intended improvements in clinical or service outcomes. We also considered some subconstructs associated with the usage of technology in ISs [103–105]. More specifically, we considered feasibility (i.e., the OCCIs can be successfully implemented, and it is simple to use them), appropriateness (i.e., compatibility for a given context and usefulness), and acceptability (i.e., satisfaction when using them). These outcomes were measured through a self-reported questionnaire, SRQ4, conducted after 12 months with managers and healthcare professionals (see Table 2).

-

Additionally, we considered penetration, sustainability, and fidelity, which were measured using anonymized data from the OCCIs completed in the RSIPA solution extracted from the baseline to the postimplementation phase (24 months). The extractions cover data from the clinical chart itself, i.e., all the forms that make up each record, plus the logging of data on daily entries and exits by professionals for modifications and consultations of these records. The chart comprised the CGA covering 6 domains with 16 major dimensions. There was also a specific module with a summary to support the structured decision-making process and care plans. Penetration is defined as the integration of a practice within a service setting and its subsystems. From a service perspective, this construct is like the reach of the RE-AIM frameworks [106] that is the coverage of the intended target groups, i.e., the number and characteristics of home-care clients assessed with the OCCIs. Sustainability is the extent to which a newly implemented intervention is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations. It was measured as the evolution of the OCCIs completed once the field study had been completed (after 12 months) until 24 months. The outcomes of penetration and sustainability are related in that higher penetration may contribute to long-term sustainability. OCCI Fidelity is the degree to which the OCCIs were delivered as intended by OCCI developers. Fidelity has been measured typically in terms of adherence, dose, and quality of the program [68, 69]. Fidelity-Adherence measures the delivery of the key components of an intervention as it was designed (i.e., structure: the element is present). Fidelity-Dose refers to the specific amount of OCCI completed, which includes the number of assessments and care plans over the study period, ranging from 0 to 12 and up to 18 months. Fidelity-Quality measures the way providers deliver the OCCIs using the overall clinical process (the different OCCI phases and subcomponents) as attended by the developers (process). Here, it also includes the use of the RSIPA IS with the OCCIs integrated. To this end, we reviewed the content of the overall assessment and determined the prevalence of user care needs, preferences, and goals; their involvement in the goal-setting process; and the planning of services/interventions. It was impossible to link data from the RSIPA solution to the e-CLSC (SIC) database, so we could not estimate study services. Lastly, a total fidelity score was calculated. We scored each component as “yes” if conducted and “no” if not. We then calculated a percentage of the number of cases (observation or record) for which the component was scored as “yes” over the total number of observations conducted and records reviewed. Here, it also included the frequency of use of the OCCIs as perceived by the professionals (available in the SRQ4) (see Table 2).

-

Research Question 4- How are OCCI outcomes perceived by managers and healthcare professionals?

-

The service outcomes were judged by how well the OCCIs were thought up by participants to improve practices that were meant to meet the needs of older people in a network of IC services. We assessed them twice: once at six months (preliminary outcomes) using the SRQ3 and again at 12 months using the SRQ4 (see Table 2). The benefits include global perspectives, quality of relationships, quality of clinical decision-making, quality of information, productivity and efficiency, interdisciplinary coordination, and coherence. Global perspectives focus on a holistic approach to care that includes understanding client needs and difficulties, while the quality of relationships emphasizes trust and continuity. Collaborative practices involve multiple professionals working together with clients and their caregivers to deliver the highest quality care. Clinical decision-making relies on quality information, which is complete, accessible, and structured. This information is used to establish one or more diagnostic hypotheses and to subsequently verify, test, and confirm the final clinical decision. It reduces time, duplication, and paper usage while ensuring productivity and efficiency. Interdisciplinary coordination ensures effective collaboration between professionals, while coherence involves resource choice, timing, and professional contributions to achieve common objectives. Results from the conference calls, observational visits, and management dashboards were considered to understand results from SRQ4 (see Figure 3).

-

Research Question 5- How are OCCI outcomes perceived by the clients of home-care services?

-

At the end of the implementation, we also evaluated a sample of ten home-care clients with caregivers per site who had been assessed with the OCCIs and exposed to computers for at least 4 months. We randomly selected them to represent various Iso-SMAF autonomy profiles. Initially, many professionals were concerned about how clients would react to using a computer at home and whether this could harm the clinical process and their relationships with them. The goal of this investigation was to use preliminary results to rapidly determine clients’ perceptions of computer use by health professionals, the clinical process for identifying and meeting their needs during assessment and care planning, and if something needed to be adjusted.

-

Specifically, we interviewed clients in their homes using standardized questionnaires, similar to those used in previous IC studies [93, 94, 107–109], concluding with two open-ended questions. The dimensions of client outcomes were: (1) Satisfaction: (a) Satisfaction in the relationship with the healthcare professional with concerns about interpersonal relations (e.g., trust, courtesy); (b) satisfaction with services delivered with concerns about the way professionals deliver services, offer choices, give advice or information about available services, and so on; (c) satisfaction with the general healthcare organization related to the accessibility of services at convenient times, the ease in obtaining appointments with a professional, and so on. (2) Empowerment: This refers to (a) the client’s involvement in decision-making, such as their perception of being able to choose the type of care and services they need; (b) interaction, which refers to the process of obtaining information or assistance to meet their needs; and (c) the level of control, which refers to the recipient’s feelings about seeking explanations or advice. (3) Perceptions about the specific process of shared decision-making using the OCCIs; and (4) perceptions about the computer use by the professional during home visits. Open-ended questions provided insights into what clients and their caregivers thought about the process to identify and meet their needs and if they had encountered any problems during their episode of care and services that, in their opinion, needed improvement.

-

Research Question 6- What are the links and plausible causal pathways between determinants, strategies, and outcomes?

-

The IRLM [73] advances the traditional logic model for the requirement of implementation research and practice. It provides a means to describe the complex relationships between determinants, strategies, and mechanisms, leading to positive outcomes under a compact visual depiction of the implementation project. Mechanisms are processes through which strategies operate to affect their desired outcomes [110].

-

To facilitate interpretation and linkages, the potential mechanisms observed were mapped to the work of McHugh et al. [111] and the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy V1 (BCTT) [112, 113]. The BCTT consists of 74 behavior change methods, including 26 mechanisms of action (MoAs) or theories explaining “how” the mechanism of action works. That therefore testifies as to “why” we can expect a causal link between application of the methods and behavior changes.

-

To identify possible causal pathways and synthesize all elements of the implementation under the IRLM, the various findings were examined in parallel (i.e., descriptive case study reports and matrices produced during the different phases of the study to answer the first five questions). To build explanations linking the various components, we used an iterative analytical process including pattern matching, explanation building, cross-case analysis, and a concept mapping approach. First, we used predetermined questions and hypotheses to look at all the data within and between sites. We then looked for certain factors or elements that seemed to be most responsible for certain outcomes (like a high, moderate, or low level of acceptability) based on a number of plausible theoretical mechanisms. “What were the strategies that occurred over time that have favored the OCCI fidelity?” or “How and why did this outcome occur or not, or in this way, in this site, but not in other sites?” are examples of questions.

-

We formulated the hypotheses using our OCCI logic model and the conceptual frameworks or models employed in this study. We also considered the unified theory of acceptance and usage of technology (UTAUT) [105, 114, 115] with its eight underlying theories (theory of reasoned action (TRA [116]), technology acceptance model (TAM [117]), motivational model (MM [117]), theory of planned behavior (TPB [118]), combined TAM-TPB [119], model of PC utilization (MPCU [120]), innovation diffusion theory (IDT [121]), and social learning theory [122]. For example, based on the UTAUT model, one hypothesis stated that if a person perceives an innovation as useful and simple to use, she will be more likely to use it. Moreover, positive social influence and support will strengthen their intention to use the innovation.

-

In certain situations, we found alternative factors or other combinations that could have produced the same or unintended results, and therefore, we conducted a literature review to describe and support these observed patterns. We have also thought about possible counterfactual explanations many times during interpretations, using frameworks, theories, literature reviews, and our practice-based view. We shared our analysis and interpretations with the wider research team to verify and discuss the selection of certain elements over others. To organize and capture all this information, we drew out in parallel possible common or diverging patterns through the cases using a graphical tool such as concept maps (CMapTools software) that illustrate relationships between all components using labels, nodes, boxes, and links [123]. Many concept maps were built, and several meetings with research members were held to check that concepts and links were adequately reflected. At this stage, it was often necessary to go back and forth to the literature and the cases to review some findings and interpretations. Thus, the maps were frequently revised, and several of them were connected under a plausible main pathway. When the maps were deemed good enough, the final step was to make them easy to understand, and we presented them in a logical way by telling a story about the most likely causal pathways. Lastly, the IRLM was completed to summarize the findings across sites and illustrate the relationships between determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and outcomes (implementation/services/home-care clients).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 in the Additional file 2 show details in participation rates and sociodemographic characteristics of participants in response to quantitative questionnaires SRQ1 (before implementation), SRQ2 (after training), SRQ3 (6 months after implementation), and SRQ4 (12 months after). Overall, the managers involved in the project at the three sites returned participation rates from 81%–100% for SRQ1, 80%–100% for SRQ2, 78%–89% for SRQ3, and 70%–100% for SRQ4. The managers at the three sites were mostly women with a high level of education (29%–77% with a master’s degree) and a full-time job. They had nearly 20 years of experience in home-care services. The participation rates of the professionals ranged from 57%–95% for SRQ1, 60%–86% for SRQ2, 57%–100% for SRQ3, and 48%–100% for SRQ4. Most of the professionals had a bachelor’s degree; those at Sites A and B were more experienced than those at Site C.

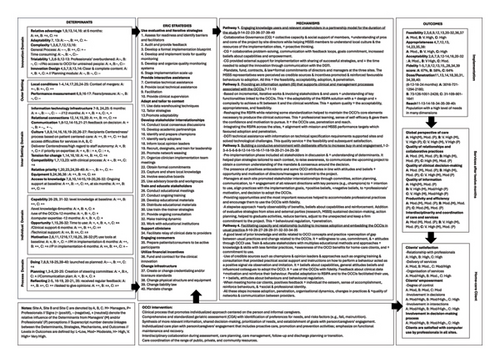

The next section describes results according to each research question. To prevent recurrence of some findings, we underlined only the most relevant information for understanding the plausible underlying mechanisms leading to outcomes. A summary of results and links between specific determinants, strategies, mechanisms, implementation outcomes, and OCCI outcomes is illustrated through the IRLM see Figure 6 at the end of the results section.

3.2. Research Question 1: The Determinants

Overall, the three sites perceived 35 facilitators and 12 barriers similarly, while each site perceived differently 38 other determinants. The barriers belonged more to the innovation domain, inner setting domain, and outer setting domain, while facilitators were linked to the implementation process domain and individuals domain. According to the CFIR 2.0 Framework Guidance, we briefly describe below each domain (in bold) with their constructs and subconstructs, which are the most significant (in italics). Detailed information on the identified determinants acting as facilitators or barriers during OCCI implementation can be found in the Additional file 3. The first column of the IRLM (Figure 6) also summarizes them.

Concerning the I. innovation domain, from the outset, the participants from all sites recognized that the OCCIs were evidence-based (I.B) and offered several advantages compared to past practices (I.C). In return, they considered them very time-consuming, complex, and lengthy (complexity, I.F.), and the care plans were not user-friendly (design, I.G.). Innovation Adaptability (I.D.) was a great concern before and during the study; several changes have been made to either the RSIPA solution or to the OCCIs. Additional file 4 shows these adaptations made according to the three phases of the OCCIs (assessment, synthesis, and planning).

Under the II. outer setting domain, local conditions (II.C), financing II.F), and performance pressure (II.G.3) were noted as barriers. The study highlights the negative impact of reform on health care (local conditions), including instability, but acknowledges the need for improvement, despite resource constraints and accessibility issues. All sites evoked fears about the performance targets linked to MSSS accountability (G.3. performance pressure). The MSSS assured project implementation would be considered without penalty, but 6 months later, managers remained concerned about reaching targets, but professionals did not perceive this pressure.

In the III. inner setting domain, sites shared numerous common facilitators, including effective collaboration to implement changes, the ability to solve clinical problems, and the appreciation of interdisciplinary and intersectional practices within and between teams/services (III.B relational connections). Sites have built on their existing working relationships and organizational units to seek consensus around their implementation decision to increase the commitment of all parties (III.D—Culture). Professionals were receptive to change (III.E. Tension for Change) despite the healthcare reform and resource restrictions (III.J.1 Available Resources—Funding). Professionals at Sites B and C recognized that the OCCIs were compatible with their clinical process (III.F. Compatibility).

On the other hand, there were significant organizational changes with significant turnovers of managers and professionals, exhaustion, overburden (III.A.3 Work infrastructure), and communication issues (III.C). The project faced IT infrastructure issues (III.A.2.) at Sites B and C, including data loss, system instability, and internet access issues, which were more prevalent at these sites than at Site A. After 12 months, most professionals at three sites considered establishing connections to the RSIPA or the internet acceptable. Site A found the funding (III.J.1) offered by the MSSS inadequate and did not consider OCCIs compatible (III.F) with their clinical process. All participants received the necessary training and clinical support (III.K. Access to knowledge), although it was less observed at Site C.

On the topic of IV. individuals domain, all sites also evidenced a good level of knowledge and self-efficacy with the various concepts and clinical processes targeted by the OCCIs (IV. Characteristics—B. Capability). After 6 months, all professionals expressed their confidence, expertise, and ability in using RSIPA functionalities and OCCI components. Nevertheless, they indicated that they still needed sessions to increase their knowledge and understanding of specific aspects (e.g., how to manage risk factors) (IV.A. Needs). The teams received necessary clinical and technological support, with an acceptable delay. However, they expressed ambivalence about sufficient time to assist with OCCIs usage (IV.C. Opportunity). After 12 months, all professionals demonstrated high confidence in using RSIPA functionalities for assessment, shared decision-making, and care planning, with Sites A and C experiencing difficulties with scales and plan generation (IV.B. Capability). Except for Site C, the good level of motivation (IV.D) observed among both managers and professionals has been a facilitator.

Under the V. process domain, many activities were accomplished in sequence from the preimplementation phase to the end of the study. Concerning deployment, only Sites B and C adopted a stepwise approach with small steps, obtaining some success before going to a larger deployment (V.G. Doing). A monitoring committee representing members of the MSSS, CESS, research team, project managers, and representatives from the selected pilot sites was formed and maintained for the duration of the study (V.A. Teaming). This committee allowed for discussion of the priorities, preferences, and needs of the interest holders at each site (V.B. Needs). All sites developed and followed their own action plans with strategies that varied little between sites, even if the observed barriers and facilitators were different (V.C. Assessing Context, V.D. Planning, and V.E. Tailoring Strategies). At all sites, the use of a steering committee with a project coordinator that tracked implementation via monitoring strategies allowed to ensure that the activities were carried out as planned (V.H. Reflecting and evaluating). During these meetings, they also involved champions and local opinion leaders from the clinical field in the hopes that they will influence colleagues to adopt the OCCIs (V.F. Engaging).

3.3. Question 2. The Implementation Strategies

Additional file 5 describes the implementation strategies that were linked to the CFIR determinants and mapped to the ERIC tool to facilitate analysis and interpretation. Through the 8 groups, 40 strategies were commonly adopted across all the sites. Most of them had been planned from the study’s outset. Their selection was based on managers experience with previous implementation projects in our healthcare system. Considering the different deployment approaches at the three sites, some strategies were used to varying degrees for a dozen of them. The highest number of strategies fell within the group of “develop interest holder interrelationships (12),” followed by “train and educate interest holders” (8) and “use evaluative and iterative strategies (6).” Four strategies were linked to “provide interactive assistance” and “change infrastructure.” Three were used to adapt and tailor the innovation to the context. There was only one strategy mapped in each group labeled “support clinicians,” “engage consumers,” and “utilize financial incentives.”

3.4. Question 3. The Implementation Outcomes Perceived by Managers and Healthcare Professionals

3.4.1. Feasibility

Overall, Site B found the OCCI components and the RSIPA functions easy to use, followed by Sites C and A (see Table 1 in Additional file 6). Ease includes the use of sections such as assessment, risk factor assessment, client and caregiver need information, professional analysis, recommendation, and disciplinary plans. Sites A and C professionals found it challenging to effectively utilize the health-status domain, psychosocial situation, and decision-making process. Except for those at Site C, none of the professionals found it easy to complete the interdisciplinary or services plans (compared to the disciplinary plan), or they did not complete them. Except for Site B, professionals from Sites A and C did not really appreciate using the scale and the automatic plan generation function.

3.4.2. Appropriateness

Managers at Site C were more likely than those at Sites B and A to agree that the OCCIs were useful for their teams (see Table 2 in Additional file 6). Apart from the interdisciplinary and services plans, all professionals considered all the above elements useful/very useful. Most RSIPA functionalities were considered useful by all participants, but professionals from Sites A and B did not find so useful functions such as “using scales,” “open all or close all,” “add/modify a group,” or “automatically generate the plan.”

3.4.3. Acceptability

Globally, professionals from Site B were very satisfied with almost all components, more so than those at Site C (see Table 3 in Additional file 6). The professionals at the three sites strongly appreciated the SMAF, the economic conditions, and physical environment domains in the assessment as well as the global expectations and capabilities/strengths sections in the synthesis. Conversely, professionals from Sites A and C were less satisfied with domains such as health status, psychosocial situation, and the use of risk factors.

3.4.4. Fidelity, Penetration (Reach), and Sustainability

Regarding fidelity dose and penetration, at baseline, the number of trained providers who delivered the OCCIs was higher at Site A (n = 72) than at Sites B (n = 13) and C (n = 10). Throughout the year, it increased very slowly to 87 at Site A, 15 at Site B, and 28 at Site C. After 12 months, deployment at all the sites was broad. The number of trained professionals increased in such a way that the number of OCCIs completed between 12 and 24 months rose sharply from 721 to 2180 at Site A, from 126 to 2428 at Site B, and from 109 to 1641 at Site C. From baseline to 12 months, the OCCIs were mostly used by nurses and social workers at Sites A (77%) and C (97%) compared to Site B (41%). Other professionals included occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and respiratory therapists. After 24 months, the proportion of nurses and social workers using the OCCIs increased to 84% at Site A and 78% at Site B but remained stable at Site C (96%).

Additional file 7 presents the characteristics of home-care clients assessed at each site with the OCCIs (Reach). After 18 months, 1074 clients at Site A, 986 at Site B, and 850 at Site C had at least one assessment completed. Briefly, we can confirm that this clientele had multiple complex needs. Around 60% of clients had moderate levels of disability (ISO-SMAF profiles 4 to 9). The proportion of clients with a low level of disability, requiring help mainly with domestic activities (profiles 1–3), was higher at Site A than at Sites B and C. As a result, the proportion of clients with a high level of disability (profiles 10–14) was greater at Sites C and B than at Site A. Clients in this category are often eligible to enter a nursing home since they usually require more than 3 hours of nursing care and assistance per day. Nearly half the clients were at moderate risk of malnutrition and about 10% at high risk. On average, about 8–12 needs were identified for the 16 clinical dimensions assessed. Care goals retained for care planning were frequently associated with ADLs and psychosocial situations. Some less prevalent needs at assessment, however, were chosen in care planning more frequently, such as special care, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and economic conditions.

For fidelity, we first described the following clinical process (see Table 1 in Additional file 8): Nearly, all professionals consulted the client’s records in preparation for home visits. Except at Site A, most professionals documented this information in the OEMC before the visit. Professionals filled one OEMC on average per client per year. In some cases, the delay in obtaining a second assessment was about 5 months at Sites A and B, compared to 3 months at Site C. The professionals filled out all the assessments because they could not advance to the next phase without finishing all the sections. Professionals primarily generated the summary in the presence of the client, as they completed the assessment at the office. Almost all professionals discussed the prioritization of needs and care planning in the presence of the client or caregiver. Most home-care clients at all sites had at least one care plan after the first assessment. The delay between an assessment and a care plan was about 20 to 38 days in the first year, but it decreased at all sites in the second year (17 to 25 days).

During the care planning process, about half of the professionals participated in interdisciplinary discussions. The proportion of professionals participating in interdisciplinary discussions varied considerably when allocating services. Most of the care goals had at least one planned intervention. After 12 months, 5%–13% of goals were modified, with 24%–46% not achieved.

A fidelity score for adherence and quality was calculated, and Table 2 in Additional file 8 gives the details. Overall, the total score was slightly higher at Sites A and C than at Site B. In preparing for the assessment, only the professionals at Site A needed to improve the documentation of the OEMC before the home visit. They also needed to improve how to document difficulties with the drop-down during the assessment. In the synthesis, professionals at all sites should have learned how to transfer needs directly to the plan to save time and to complete the summary in the client’s presence. The loss of points in this phase was also attributed to the difficulty in retaining goals related to client care preferences, which might have been influenced by the available services. Despite not fully appreciating the PSIAS care planning module (French acronym: PSIAS for planification des services individualisés et d’allocation de services), most professionals successfully completed the necessary planning. The study found challenges in interdisciplinary and intersectoral practices, possibly due to the lack of interoperability within the ISs. After a year, professionals used the computer with the client at home frequently at Site B and moderately at Sites A and C, with connection, unsanitary environments, and speed issues being common reasons. There was also a sense that the computer acted as a barrier to the client’s relationship.

3.5. Question 4. The OCCI Outcomes Perceived by Managers and Healthcare Professionals

They were investigated after 6 and 12 months (see Additional file 9). After 6 months, we observed that the effects were quite moderate. A large percentage of Site B and C managers had a positive perception of using the OCCIs to support many practices, while their professionals often saw few benefits. According to professionals from Sites B and C, the enhanced OEMC provided a better understanding of the specific situation of the clients, helped to better identify their needs, and facilitated the collaborative practices between professionals and with home-care clients, as well as enabling them to make better clinical decisions. Additionally, they considered that it yielded a higher quality of information relevant to developing care plans. Conversely, at this moment, neither site agreed that the OCCIs could better guide clients across the continuum of services or produce benefits in terms of productivity and efficiency. In fact, even if it increased the time in the client’s presence, it also increased the time to complete records. Most professionals did not see any positive effects for many dimensions of practice; 30%–50% indicated that they did not observe positive effects (see Table 1 in Additional file 9).

After 12 months, the situation had greatly changed. Generally, for most dimensions of practice, Sites B and C managers and professionals strongly agree with OCCI benefits, while Site A professionals moderately agree. Most managers and professionals agreed that the OCCIs promoted a better quality of information relevant to service planning, a better understanding of the specific situation of clients, and a better definition of appropriate interventions and took more account of the contribution made by clients and by the public and community networks. The managers at Sites B and C had a more positive opinion than professionals about the quality of relationships and collaborative practices. Unlike managers, professionals at all sites did not agree that the OCCIs reduced errors and allowed a better exchange of information between professionals. Considering the productivity and efficiency dimension, the OCCIs seemed to reduce the repetitions, did not affect the delay between a request and the provision of service, and did not increase the volume of paper. In contrast, they did not reduce repeated calls between professionals but still increased the time required to complete client records. In terms of interdisciplinary and coordination, the managers at Sites B and C agreed that the OCCIs improved all aspects of this dimension. Those at Site C also agreed, but in a lower proportion according to subdomains. This site already had interdisciplinary issues before the study (see Table 2 in Additional file 9).

3.6. Research Question 5. The OCCI Outcomes Perceived by Home-Care Clients and Their Caregivers

This section concerns the preliminary results for the interviews with home-care clients on how they perceived the clinical process using the OCCIs and a computer during assessment. Site C had trouble recruiting 10 participants given the criteria that the client had to speak and understand French and be exposed to computer use during the assessment. Due to the small sample size and skew distributions, we have no power to detect any difference across sites. While the results must be interpreted with caution, they are nevertheless informative. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1 (Additional file 10). The mean age varied per site from 73 to 85 years old. Almost 40% of elders had a good or very good perception of their general health status, while 33% did not have the capacity to answer that question. A proportion of 13% of clients had a low level of disability (i.e., Iso-SMAF profiles 1 to 3); approximately 67% had a moderate level of disability (profiles 4 to 9) and 20% of clients belonged to profiles 10 to 14, which represent a high level of disability.

Concerning satisfaction (see Table 2 in Additional file 10), the clients at all sites had a high level of general satisfaction with health care and services. Under the relationship dimension, clients underlined that professionals were courteous, honest when answering questions, and used easy-to-understand language. They felt they could trust the professionals and were satisfied with respect for privacy. They were less satisfied, however, about not always having the same professional each time. In terms of service, clients were mostly satisfied when it came to receiving information on the services available, where to go, what to do, and so on. They were less satisfied regarding receiving information about their different choices and the fact they were not encouraged to get support from their caregivers. Clients were mostly satisfied with the accessibility of services at convenient times and the ease and speed of obtaining appointments, and so on, but they were somewhat dissatisfied about the number of steps it took to obtain the help they wanted.

Concerning involvement in decision-making (see Table 3 in Additional file 10), clients felt that they could decide what care and services they needed and the type to receive but that they could not decide how much. They felt that their choices were respected, they received all the information they wanted, and they got the help they needed. Their level of control about asking questions, requesting explanations, or asking for advice, however, was relatively low. Concerning the process of shared decision-making associated with the OCCIs (see Tables 4 and 5 in Additional file 10), all clients considered it was very/extremely important that professionals give them all the necessary information to decide which needs should be prioritized, that professionals pay attention to their understanding of each need discussed, and apprize them of the risks and advantages of the options for care and services. When we asked the clients how they perceived these actions in their cases, most felt that professionals paid a lot of attention to their understanding of each need discussed. In contrast, only 60% of them felt other actions had been taken in their cases.