Do a Clinical Practice Guideline Facilitate Shared Decision-Making? Development of a French Assessment Tool Using the Delphi Consensus Method

Abstract

Background: Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a prime component of medical practice. EBM often translate into clinical practice guidelines (CPG) widely used by healthcare providers. However, CPGs are often focused on a specific pathology, and they rarely make a room for shared decision-making (SDM) another key dimension, centered on the information exchange between the physician and the patient, the deliberation/discussion, and the decision made based on a common agreement. An assessment tool is therefore needed to determine whether the structure of CPGs allows or not the integration of SDM.

Objectives: To develop an assessment tool in French that could quantify the degree to which CPG facilitate SDM by translating and adapting the elements developed in international consensus studies.

Method: A Delphi consensus method including seven experts selected from the leading scientific community on the topic. Consensus was considered to have been reached when the approval rate reached 70%.

Results: A consensus for the adaptation, relevance, and adjustment of 19 strategies was reached after three rounds. Based on these strategies, 17 criteria were developed. They include general strategies such as adding a specific chapter on SDM, using wording that makes patient involvement explicit, presenting outcomes, benefits and harms of all options including “doing nothing,” and recommendation-specific strategies such as giving to the patient a copy of his/her personalized treatment plan, recommending which patient decision aid could be used and when, or encouraging the patient to exchange with close relatives and friends for the discussion.

Conclusion: We developed a 17-item tool to assess whether or not a CPG facilitates sustainable development. This tool will have to be tested to ensure that it is easy to use, relevant and reproducible, and thus meets the expected quality criteria. Such a tool would enable researchers and patients alike to assess CPGs using a common benchmark, would support national and international benchmarking processes, and provide a starting point for future improvement. Translations into other languages could broaden the scope of use.

1. Introduction

Decision-making (DM) in medicine is a multidimensional process including various objective and subjective factors that are often intertwined. DM is influenced by emotions [1] and several key concepts such as uncertainty [2], cognitive and heuristic biases [3], thought speed, and bounded rationality [4]. In the medical encounter, all these factors impact both the patient and the healthcare professional.

Within the concept of evidence-based medicine (EBM), Sackett et al. [5] proposed in the mid-nineties a method in which DM is divided into three categories: the current state-of-the-art according to the medical research at any given moment, the results of medical experience including theoretical knowledge and experience, and the patient’s values and preferences. EBM has since been defined as the benchmark DM method. One of the most widely used structured expressions of this method is the clinical practice guidelines (CPG). We used the US National Academy of Sciences’ definition for CPG: CPGs are statements that include recommendations for optimizing patient care and are based on a systematic review of the evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options [6]. CPGs are often seen as practice modelers as they both provide a synthesis of scientific data and the approaches these data lead to, and play a reference role for healthcare professionals who are, for some, reluctant to deviate from them [7]. Nevertheless, CPGs are not always being used notably because for some, the DM model should be determined by the clinical encounter participants and not by a CPG [8].

Moreover, despite their origins, CPGs do not systematically include all the key concepts included in its definition. It has shown, for example, that decision-support mechanisms relating to patients’ values and preferences are relatively absent from CPGs [9–11]. According to some authors, this absence may also be responsible for some of the difficulties in promoting a patient-centered approach [11].

At the same period, the concept of shared decision-making (SDM) has been developed in Western European countries with the aim of moving away from the classic paternalistic approach [12, 13]. For Charles et al. [13], it enables patients to take an active part in their healthcare DM process, thus respecting the principles of individual autonomy. Physician and patient share and discuss information to reach a decision based on a mutual agreement [13, 14]. SDM has shown to promote patient participation in decisions concerning their health, improve quality and safety of care, and provide a conceptual framework when situations require individualized decisions [14–16].

A number of studies have suggested that SDM, as a defined process supported by decision-support tools, could address the shortcomings of CPGs by enabling patients’ values and preferences to be taken into account in the DM process [17, 18].

Several authors point out that in their current form, CPGs have difficulty in taking account of patients’ specificities and preferences: even when they seek to adapt to a particular audience, they remain limited by a quest for management applicable to all. These same authors recommend working on the way CPGs are designed rather than on how they are applied [19, 20].

By integrating SDM, CPGs may be able to move conceptually closer to the EBM, while promoting a patient-centered approach. However, integrating SDM into CPGs is a complex process. Simply mentioning SDM or suggesting its use as an accompaniment to a DM process that remains essentially scientific has not proven effective in bringing about changes in practices [21, 22].

The SDM community believes that it is necessary to include SDM in the design of the DM process in order to bring about changes.

In this respect, this community has already suggested recommendations to be taken into account when designing CPGs as part of a large-scale study involving several exchange groups between more than 75 experts in the field, both carers and patients, taking place over two sessions of the international SDM congress [23]. What is lacking today is a tool to assess the impact of these changes. We need a tool which is capable of assessing whether or not a CPG promotes the use of SDM in order to determine whether the various proposals promoting the integration of SDMs into CPGs are applied and associated with objective changes.

However, the literature does not provide any scales for evaluating SDM at the level of CPGs. There is therefore a gap which hinders this evaluation and therefore potential SDM development.

In this context, the aim of our study was to develop a tool into French to assess the extent to which CPGs facilitate or not SDM. The tool is based on strategies proposed by Van der Weijden et al. [23] that we first translated into French, taking into account the diversity of French dialects.

This would enable researchers and patients to assess CPGs using a common reference, support national and international benchmarking processes, and provide a starting point for future improvements.

2. Methods

We conducted a qualitative expert consensus study, using the Delphi method, to define French assessment criteria able to evaluate whether a CPG facilitates or not SDM.

2.1. Expert Recruitment

The Delphi consensus method requires a minimum of four to six content experts [24]. Since 2014, the FREeDOM Collaboration (French Collaboration on SDM) gathers French-speaking experts on SDM. Experts are defined as researchers who have already published scientific articles on the subject and are identified as such by the scientific community. We contacted them and they provided us with a list of eligible experts whom we contacted by e-mail with a reminder after 14 days if there was no response [25]. Experts who agreed to participate received a personalized email collecting their consent and complete an online survey on the Google form platform.

2.2. Delphi Process

The Delphi consensus method consists in structuring the group communication process to achieve consensus; this can be done using online or e-mailed surveys to gather experts’ opinion over a series of rounds until consensus is reached [24, 26]. This requires a preliminary search to elaborate or identify a relevant questionnaire.

We decided to base our work on the recommendations published by Van der Weijden et al. [23]. It is a key reference in the field of SDM, designed with the participation of the vast majority of experts in the area. We took all the 19 strategies proposed in the article and submitted them to a panel of experts in order to develop a French tool able to evaluate whether a CPG facilitates SDM or not. Recommendations were extracted from the original article and formulated into sentences. A preliminary translation from English to French was done by two individuals (PP and AD) whose first language is French (France). They worked separately before comparing and combining their propositions, and discrepancies on this initial phase were resolved by the study coordinator (YMV). This resulted into 19 initial criteria which we submitted to experts both in the English original version and in a preliminary French version. For each criterion, experts were asked to evaluate whether the criteria were relevant for evaluating SDM in CPGs using a seven-point Likert scale. They could also suggest modifications in a comment box. They were also asked to evaluate the accuracy of the French translation in comparison to the English version. They could also suggest modifications that would integrate the differences in dialect between Canada, France, and Switzerland.

We planned to conduct three rounds of questionnaires to reach a consensus. The first round consisted in the evaluation, both of the translation and relevance, of each criterion of the initial questionnaire. With the help of feedback from the experts, the two translators had to adjust the translations, with the involvement of the study coordinator in the event of disagreement. The second and third round consisted, respectively, in feedbacks of the quantitative (percentage of consensus), and qualitative (comments and suggestions) results of the previous round, as well as evaluation and comment on the new version of nonconsensual criteria. In case of persisting disagreement at the end of the third round, experts were invited to meet by video conference as allowed by the modified Delphi method. Experts had 15 days to complete each round. Up to two individual reminder e-mails were sent in case of nonresponse. Investigators could ask experts to specify any missing response in his/her questionnaire. The study was continued if a minimum of four experts replied to each round.

2.3. Analyses

Consensus on the relevance and translation of each criterion was determined by a quantitative analysis of the Likert scale responses. Each criterion was evaluated with two different Likert scales, one for the translation and one for relevance. Consensus was defined as 70% of similar responses on the Likert scales [27]. This means that a strategy would be included if it obtained at least 70% of scores above five, and conversely would be excluded if it obtained 70% or more responses under three. We defined the 70%-threshold based on the methodological reference work of the Delphi rounds which recommend a value that is consistent and applicable to our expert group size. Thus, with seven experts, we considered that a consensus of five experts, i.e., 71.4% rounded down to 70%, would be sufficient for the purpose of this study [24, 28, 29]. Consensus had to be reached for both relevance and formulation (including translation and adjustments) of the criterion.

A qualitative analysis of all comments and suggestions made by the experts was conducted by two researchers (AD and PP) who synthetized the proposed modifications according to the different feedbacks separately before pooling their proposals thus leading to new formulations. These new formulations were reviewed by a third investigator (YMV), expert in SDM. In addition to the new version of each criterion, specific comments were detailed and submitted to the experts in the following round (Table 1). The experts gave their opinion on each proposed change between rounds. The final round was deemed to have been reached when each of the 19 criteria had been accepted or rejected by at least five experts. The selected criteria were then compiled in the final version of the tool.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

3. Research Ethics

This study does not involve research on humans or animals and therefore does not require the formal approval of an ethics committee under French regulations. The research study was discussed by the researcher with the participants, and written consent was obtained from all participants.

3.1. Funding

This study was carried out by the FREeDOM Collaboration and was not funded by any external source.

4. Results

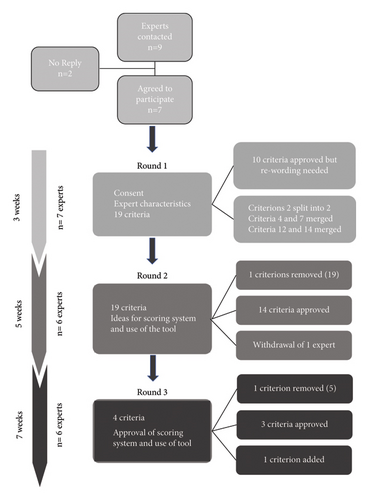

The panel of experts reached consensus after three rounds from February 2021 to June 2021 (Figure 1).

4.1. Expert Panel for Evaluation and Comments on Each Criterion (Translation and Relevance)

Among the nine experts contacted by e-mail in January 2021, seven agreed to participate (Table 2). One expert took part only in the first round and the other six completed all three rounds. They are Canadian (Quebec), Swiss, and French covering variations of the French language. All experts speak, write, and read English and French fluently. All the experts were multiskilled decision professionals who had been working in the field for an average of 15 years.

| Expert | Sex | Country | SDM experience (years) | Specialty or position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Canada | > 20 | Family doctor |

| 2 | Female | France | > 20 | Researcher |

| 3 | Male | France | 5–10 | Family doctor |

| 4 | Female | The United States, Switzerland, and France | 15–20 | Researcher |

| 5 | Male | France | 5–10 | Anesthetics and resuscitator |

| 6 | Female | Canada | 10–15 | Family doctor |

| 7 | Male | Switzerland | 10–15 | Family doctor |

4.2. Rounds

Across the three rounds, the panel of experts established 20 criteria able to assess the extent to which CPGs facilitate or not SDM (Table 3).

| Proposals taken from the TDWV article: original English strategy | Initial translation | Result Round 1 | Result Round 2 | Result Round 3 | Round 3—final result-translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unchanged |

|

|

|

|

|

Unchanged |

|

|

|

|

|

Unchanged |

|

5. For each recommendation, details for all relevant outcomes of all options are presented including expliciting the option of doing nothing, or close monitoring. Benefits and harms of each option, outcomes that patients consider especially relevant such as quality of life, duration of hospitalisation, and number of revisits or recovery time. These can influence decisions in case large variation in patient preferences |

| 5. Display evidence about patients’ actual decisions, attributes, and adherence to treatment and about professionals’ prejudice against patient preferences. Evidence generated by quantitative or qualitative studies |

|

La RBP affiche des données—provenant d’études qualitatives ou quantitatives—sur les options effectivement choisies par les patients, sur l’observance, et sur les à priori des professionnels à l’égard de ces choix, c’est-à-dire ce que les professionnels pensent que les patient préfèreraient ou choisiraient versus ce qu’ils choisissent vraiment | La RBP affiche des données destinées aux professionnel.le.s—issues d’études qualitatives ou quantitatives—rapportant par exemple les options les plus fréquemment choisies par les patient.e.s, les données d’observance ou encore les a priori fréquents des professionnel.le.s à l’égard de ces choix (ce que les professionnel.le.s pensent que les patient.e.s choisiraient vs. ce qu’ils choisissent vraiment) | Criterion removed | 5. Criterion removed |

| 6. Provide illustrations of patients’ deliberations to highlight the importance of patient involvement. For example, a vignette of a patient and provider discussing options to reach a shared decision. Showing how a patient would choose something other than the first recommended option |

|

La RBP fournit un exemple court (échange entre un professionnel et un patient ou la réflexion d’un patient) dans lequel les préférences du patient influencent la décision finale, pour encourager le professionnel à délibérer avec le patient | La RBP fournit un exemple court (discussion entre un.e professionnel.le et un.e patient.e ou la réflexion d’un.e patient.e) dans lequel les préférences patient orientent vers une autre option que celle habituellement proposée en première intention, pour encourager le/la professionnel.le à délibérer avec le/la patient.e | La RBP fournit un exemple court (échange entre un.e professionnel.le et un.e patient.e ou la réflexion d’un.e patient.e) dans lequel les préférences des patient.e.s influencent la décision finale, pour encourager les professionnel.le.s à délibérer avec le.s patient.e.s | 6. The CPG provides a short illustration (patients or a patient and provider discussing options to reach a shared decision). Showing how patient preference influence the final decision to encourage providers to deliberate with the patient |

| 7. Describe a second best or alternative option | Décrire une “deuxième meilleure” ou une autre option | Removed considered redundant with 4 | X | X | 7. Removed, considered redundant with 4 |

| 8. Flag those recommendations for which incorporating patient preferences are urgent. A star or symbol reminding the clinician that at this point it is very important to share with the patient |

|

Les recommandations pour lesquelles il est impératif d’intégrer les préférences du patient sont signalées par une étoile ou un symbole rappelant au professionnel de santé qu’à ce stade, il est particulièrement important de partager le processus décisionnel avec le patient | Unchanged | Les recommandations pour lesquelles les préférences des patient.e.s exercent classiquement un poids important sont signalées par une étoile ou un symbole rappelant aux professionnel.le.s de santé qu’à ce stade, il est nécessaire de partager le processus décisionnel avec le/la patient.e | 7. The CPG flags those recommendations for which patient preferences usually influence the decision using a star or symbol to remind the clinician that at this point it is very important to share the decision-making process with the patient |

|

|

|

Unchanged |

|

8. The CPG describes who does what in guiding the patient through the decision-making process. It suggests when is it appropriate to call on a multidisciplinary team or to delegate certain aspects to other professionals (social workers or psycho-educated personnel and trained oncology nurses) |

| 10. Recommend that the patient receive a copy of the individualized treatment plan | Proposer que le patient reçoive une copie du plan de traitement individualisé | En cas de réalisation d’un programme personnalisé de soin, il est recommandé que le patient en reçoive une copie adaptée à sa littératie et numératie en santé | Unchanged | En cas de réalisation d’un programme personnalisé de soin (France)/plan de soin individualisé (Québec), il est recommandé que le/la patient.e en reçoive une copie adaptée à sa littératie et numératie en santé | 9. If an individualized treatment plan (Quebec)/personalized treatment programme (France and Switzerland) is elaborated, and the CPG recommends that the patient receive a copy adapted to his/her health literacy and numeracy |

| 11. Recommend that the professional encourage the patient to engage a proxy in the deliberation. Such as a partner, parent, another family member, or friend |

|

La RBP recommande au professionnel d’inviter le patient à faire appel à un tiers de son choix pour l’aider dans la réflexion s’il le souhaite | Unchanged | La RBP recommande au professionnel.le d’inviter le/la patient.e à faire appel à un tiers de son choix pour l’aider dans la réflexion s’il/elle le souhaite | 10. The CPG recommends that the professional encourages the patient to engage a proxy in the deliberation if he/she so wishes |

| 12. Provide specific questions to ask patients about their values to prepare them for the deliberation | Prévoir des questions spécifiques à poser aux patients concernant leurs attentes afin de les préparer à la discussion | La RBP fourni des questions visant à identifier les valeurs et préférences des patients afin de les préparer à la phase de discussion ou elle oriente vers des outils de clarification des valeurs et préférences | La RBP fournit une liste de questions visant à identifier les valeurs et préférences du patient (le cas échéant en s’aidant d’outils d’aide à la clarification des valeurs et préférences) ainsi qu’une liste indicative de points qu’il serait utile d’aborder lors de la discussion | La RBP fournit une liste de questions visant à identifier les valeurs et préférences du patient.e (le cas échéant en s’aidant d’outils d’aide à la clarification des valeurs et préférences) ainsi qu’une liste indicative de points qu’il serait utile d’aborder lors de la discussion | 11. The CPG provides a list of questions to put in light patient values and preferences (if necessary using a value clarification tool) and a list of topics to discuss during deliberation |

| 13. Recommend which patient decision aids should be used and when | Préciser quelles aides à la décision du patient doivent être utilisées et quand | La RBP recommande des outils d’aide à la décision destinés aux patients, à quel moment les utilizer, ou elle oriente vers un inventaire d’outils d’aide à la décision régulièrement mis à jour | Unchanged | La RBP recommande des outils d’aide à la décision destinés aux patient.e.s, tout en indiquant à quel moment les utilizer, ou elle oriente vers un inventaire d’outils d’aide à la décision régulièrement mis à jour | 12. CPG recommends which patient decision aids should be used and when, or crosslinks to a regularly updated inventory of patient decision aids |

| 14. Provide a minimum list of topics and types of arguments that should be discussed | Dresser une liste minimale de questions et de types d’arguments à aborder | La RBP fournit une liste de questions visant à identifier les valeurs et préférences du patient afin de le préparer à la phase de discussion, ainsi qu’une liste de points à aborder lors de la discussion | Merged with 12 | X | 14. Merged with the criterion 12 |

| 15. Provide a step-wise communication strategy for discussing different treatment options that are tailored to subgroups of patients based on patient characteristics, such as clinical symptoms or health literacy | Prévoir une stratégie de communication par étapes pour discuter des différentes options de traitement, adaptée à chaque sous-groupe de patients en fonction des particularités du patient, telles que les symptômes cliniques ou les connaissances en matière de santé | La RBP prévoit une stratégie de communication des différentes options adaptée à chaque groupe de patients, selon leurs particularités, telles que leurs symptômes cliniques ou leur niveau de littératie en santé | La RBP prévoit une stratégie de communication des différentes options adaptée à chaque groupe de patient.e.s, selon leurs particularités, telles que leurs symptômes cliniques ou leur niveau de littératie en santé | 13. The CPG provides a step-wise communication strategy for discussing different treatment options that are tailored to subgroups of patients based on patient characteristics, such as clinical symptoms or health literacy | |

| 16. Define quality indicators and benchmarks for the decision-making process. For example, saying that using this decision aid tool is a quality indicator |

|

|

|

14. The CPG defines quality indicators and benchmarks for the decision-making process. For example, saying that using this decision aid tool can help structure the decision-making process | |

|

|

La RBP fourni des outils de communication des probabilités comme des graphiques et pictogrammes présentant les probabilités en termes de risque absolu et de réduction du risque relatif. Ils sont directement intégrés dans la RBP ou sont annexés dans un document séparé (avantage: RBP moins longue et document pouvant être consulté séparément ou remis au patient) | La RBP fournit des outils de communication des probabilités comme des graphiques et pictogrammes présentant les probabilités en termes de risque absolu et de réduction du risque relatif. Ils sont directement intégrés dans la RBP ou sont annexés dans un document séparé (avantage: RBP moins longue et document pouvant être consulté séparément ou remis au patient) | 15. The CPG incorporates risk communication tools such as charts and pictograms with absolute risk and relative risk reduction data. These can be fully integrated in the CPG or be a separate document (advantage: shorter CPG and separate document that can be looked up or given to patients) | |

| 18. Incorporate the patient decision aid and the guideline recommendation in the electronic health record to have these documents with the patient preferences available for SDM in follow-up visits. |

|

La RBP suggère, le cas échant, d’intégrer l’aide à la décision du patient et/ou la recommandation concernée dans le dossier patient informatisé afin d’optimiser la PDP lors des consultations de suivi | La RBP suggère, le cas échéant, d’intégrer l’outil d’aide à la décision du patient et/ou la recommandation concernée dans le dossier patient informatisé afin d’optimiser la PDP lors des consultations de suivi | 16. Where applicable, the CPG suggests incorporating the patient decision aid and the recommendation in the electronic health record to optimize SDM in follow-up visits | |

| 19. Provide scores on performance indicators and benchmarks to facilitate choice for a healthcare provider with a favorable profile for SDM |

|

La RBP fournit des indicateurs de performance qui permettent d’identifier plus facilement les soignants dont la pratique est plus orientée vers la PDP. Cet outil permettrait aux patients d’être conscient de ces éléments lorsqu’il choisissent un soignant ou une structure de soin | Criterion removed | Criterion removed | 19. Criterion removed |

| X | X | X | “Les patients devraient être présents sur les panels qui conçoivent les recommandations” | Un ou des patient.e.s a pris part à l’élaboration de la RBP | 17. One or more patients took part in elaborating the CPG |

4.2.1. Round 1

Round 1 was conducted from February 8 to February 27, 2021. All seven experts responded, for some after one or two reminders.

They agreed on the relevance of 10 out of the 19 criteria (> 70% of 6 “agree” or 7 “strongly agree” on Likert scales). The qualitative analysis showed that all items required rewording. They were therefore all resubmitted in the next round, even those whose relevance and translation had been validated.

The criteria that were accepted were generic strategies such as including a paragraph dedicated to SDM (Criterion #1), using wording that makes patient involvement explicit, encouraging healthcare professionals to use plain language to facilitate patient-centered communication (#2), and providing a patient version of the CPG (#3).

The “recommendation-specific” strategies that were included were presenting the details of all relevant outcomes of each option including doing nothing (#4), using a symbol to flag recommendations for which incorporating patient’s preferences is urgent (#8), providing the patient with a copy of their individualized treatment plan (#10), suggesting the patient engage a close relative or friend in the deliberation (#11), incorporating visual risk-communication tools (#17), or incorporating decision aid and/or guideline in patient’s electronic health record (#18).

The feedback from the experts was that the translation was “faithful” and “relevant” but needed to be adjusted to make it “useable” for assessment purposes, requiring several rewordings.

Experts mentioned the presence of cumbersome and redundant criteria, as well as potential difficulties in implementing it. Certain criteria could be complex to apply depending on the subject. This led us to clarify before the second round that the objective was not to have a grid applicable in its entirety to all the recommendations, but that it should be applicable in a similar way to the recommendations in the same field.

4.2.2. Round 2

Round 2 took place from March 8 to April 17, 2021. One expert decided to withdraw from the process due to lack of time. The other six experts responded after one to three reminders.

Fourteen criteria were accepted with > 70% of responses being at Level 6 or 7. Minor changes were made if they were consistent with the comments from the previous round.

Two concepts were individualized from Criterion 2, “CPG uses wording that makes patient involvement explicit” and “CPG encourages professionals to use plain language to facilitate patient-centered communication during the entire clinical pathway.”

The Quebecois term “formulaire de référence” was added as an alternative to “courier” (referral letter) used in Switzerland and France. The two translations of “personalized treatment plan” in Criterion 10 were also included “programme personnalisé de soins (Switzerland, France)/plan de soins individualisé (Québec).”

Criteria 4 and 7 were merged as they both suggested the recommendation to present details of all available treatment options, including doing nothing.

Criterion 13, “Recommend which patient decision aids should be used and when,” initially obtained 70% of responses greater than four. Counter arguments were that few decision aids exist, and that updating them was not realistic. 100% consensus was reached in the second round after an expert suggestion to crosslink a regularly updated online inventory of patient decision aids.

Criteria 12 and 14 and a part of Criterion 17 were combined into one criterion about patient value clarification.

Criterion 19, “Provide scores on performance indicators and benchmarks to facilitate choice for healthcare provider with a favorable profile for SDM,” received 83% unfavorable responses and was excluded. Experts commented it was “unpractical,” “not operational,” or “too complex to apply to CPGs.”

One expert suggested Criteria 5, 12, 15, and 16 were more suited to patient decision aids than to CPGs.

“Inclusive writing” is a way of including both genders in written French: “les patients” becomes “les patient.e.s.” The suggestion to incorporate inclusive writing techniques was validated by the expert panel although some feared it might complicate the text.

There were discussion aimed expressly at deciding on the best translation for specific SDM terminology: “délibération,” “échange,” or “discussion” were chosen equally to translate “deliberation.” “DM process” was translated by “processus de prise de decision” and “decision process” by “processus décisionnel.”

The last section of Round 2 invited experts to share their vision regarding the use, scoring/rating, and presentation of the tool. The ideas collected included presenting the tool as a checklist using a simple binary scoring system. It was accepted that not all criteria apply to all recommendations, specialties, and situations. It was suggested that the tool’s primary purpose could be to educate rather than to evaluate, and that this could be emphasized by offering feedbacks or suggestions to implement missing criteria. “In my opinion, these recommendations should all be included, even if they seem cumbersome to implement, from a formative rather than an evaluative point of view, and feedback could be recommended to implement the criteria that are not present.”

Other suggestions that came up in Round 2 were as follows: the need to continue to separate documents for patients and physicians, keeping in mind that promoting the use of plain language will facilitate patient-centered medicine and the fact that patients should be involved in CPG development.

The feedback from Round 2 revealed a duality in the experts’ comments, which was probably the source of several disagreements over the criteria. Some wanted to promote the use of SDM approaches whenever possible, while others wanted to make it a systematically possible option but no more promoted than other DM methods. This was passed on to the participants for discussion in Round 3.

4.2.3. Round 3

Round 3 was conducted from April 28, 2021, to June 20, 2021. Four experts responded within 3 weeks after one or more reminders for two experts.

Criterion 5 suggested displaying evidence about patients’ actual decisions, attributes, and adhesion to treatment as well as professionals’ prejudice against patient preferences. This later was discarded as 83% of experts agreed it might bias the decision process rather than facilitate it.

Although Criterion 6 reached 83% of approval in Round 2, a disagreement remained about its wording. The criterion suggested to provide an example of patient deliberation showing how SDM could lead to “choosing something other than the first recommended option.” Some experts argued that there should be no “first” or “second” recommended option but only one best option per patient. Others justified this criterion by the fact that most CPGs still prioritize options. The wording “patient preferences influence the final decision” was preferred by 67% of experts. An expert suggested including several examples to ensure equal presentation of options, but the group chose to recommend only one example.

Criterion 16 “Define quality indicators and benchmarks for the DM process, for example, saying that using this patient decision aid is a quality indicator” was approved by 71% of experts in Round 1. It also raised the following comments: “too complex,” “I don’t like quality indicators, this should all stay fundamentally human.” After back-and-forth discussion and one participant dropping out, no expert changed his/her mind resulting in 67% agreement in Round 3.

In Round 2, one expert suggested that the SDM Q9 and CollaboRATE questionnaires, which are used to measure SDM in clinical encounter, should be used when selecting the relevant criteria for the evaluation tool [26, 28]. In Round 3, the expert panel chose to mention them in the introduction paragraph of the tool as a way to illustrate the SDM process.

All experts agreed to include patient involvement in the development of a CPG as a new criterion. “Patients should be present on the panels that draw up recommendations.”

Four experts were in favor of a binary scoring system for the tool (Response of 5, 6, or 7/7). One expert did not respond, and one suggested adding an intermediate level in case of partial presence of a criterion—the relevance of which could be reassessed.

Finally, the closing comment of an expert for Round 3 was as follows: “It will be useful to mention that this tool belongs to a dynamic process, that nothing is perfect (such as drugs and their side effects and clinical tests and their practical limits) and that assessing the tool in a couple of years will allow for its improvement.”

At the end of the third round, 14 of the 19 initial criteria were retained after adjusting their translation and the expression of their concepts. A 15th and 16th criterion were designed by breaking down one of the initial criteria whose concept was too complex to be broken down into a single criterion. A 17th criterion was created and validated following feedback from the experts.

Of the initial criteria, four were withdrawn because they were deemed to be redundant with other criteria (two of them) or irrelevant in the context of an evaluation (the other two).

The final 17 criteria are based directly on the latest feedback from the experts, with no additional qualitative changes made by the researchers.

5. Discussion

This appraisal tool is the first to formalize a specific assessment of the extent to which CPGs attempt or not to facilitate SDM.

Given the scope and completeness of Van der Weijden et al.’s paper [23], it appeared as a sound basis for the development of our assessment tool. Their paper is based on feedbacks from international experts in SDM and CPGs and includes patient representatives, hence putting forward multiple strategies to help include SDM in CPGs [23]. Following the authors’ warning that these “potential good ideas” were not, as such, quantitative assessment criteria, it was decided, in accordance with authors, to gather a panel of experts to decide on the relevance of each item and adapt them into criteria for an appraisal tool.

In previous studies, various criteria have been used to evaluate whether CPGs facilitate SDM or not. McCormack and Loewen [10] relied on four criteria: specific mention of the importance of incorporating patient’s values and preferences in DM, quantitative (relative or absolute) risk or benefit data, data on likelihood of an outcome with and without the proposed intervention, and data on cost of possible interventions. Gartner et al. [9] relied on other elements: strength of the recommendation according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method and its consistency with content of the CPG; completeness of the presentation of risks and benefits; incorporation of patient preferences; mention of the values and preferences of panel members who designed the CPG regarding benefit-risk balance underlying a recommendation; and presence of guidance on patient involvement in DM.

It is important to note that four criteria refer to decision aids. These tools, designed for patients, summarize the different available options to help them make a choice without necessarily guiding their choice. They are distinct from CPGs, which are intended for healthcare professionals and do not deal with choice, but rather with recommended practices in the context of a specific pathology, often in a directive manner.

While these previous studies have evaluated CPGs, they were isolated qualitative evaluations without the development of standardized methods, which do not make it possible to design a generalizable evaluation tool. This is the main difference between these previous studies and our study. Their aim was to carry out a one-off evaluation of a few CPGs to illustrate the implementation of the SDM at a specific point in time, whereas our study seeks to provide a comparative tool that can be applied to all CPGs.

It is this specificity that makes our work original and useful. The current approach is structured around general implementation proposals, with “a posteriori” measurements of CPGs and the place of SDM in these CPGs. It therefore allows only a broad and contextual assessment and does not determine the potential contribution of each CPG in the field.

Our tool will allow each CPG to be assessed and compared individually, enabling a more active attitude to rate and benchmark, thus allowing more accurate and easier analysis of the evolution and implementation of CPGs.

This work has several strengths. First, the Delphi consensus method is well suited to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. Second, a rigorously developed protocol comprising a literature review and paired with the experts’ experience, assuring a high level of evidence. Third, a reliable study which brings together both new and existing knowledge on SDM in CPGs ensured a solid basis to work on. Fourth, recognized international French-speaking SDM experts further secured the scientific standard of the study. Fifth, the preliminary professional translation of the original criteria from English to French optimized the experts’ investment in each round by focusing their input on commenting and rewording. Sixth, anonymous responses on online questionnaires limit “prominent personality bias”—principal bias of expert consensus. The online Delphi method reduces organizational, geographical, and financial constraints and was particularly relevant during the COVID pandemic. The panel of experts was drawn from the only international French-speaking SDM network. They can thus be considered as representative of French-speaking experts on SDM.

The weaknesses of the Delphi method include the relatively low number of exchanges between experts and the high number of rounds sometimes needed to reach consensus. In our case, a small number of experts were solicited and patients were not included. While soliciting more experts and including patients could have improved the scope of our results, this weakness can be tempered by the variety of profiles who originally participated in the Van der Weijden et al.’s study. The experts’ lack of availability during the pandemic period led to longer response times and multiple call-backs in order to obtain significant results. In order to ensure a personalized follow-up of answers and reminders, and to obtain clarifications in case of incomplete questionnaires, investigators were not anonymous. This could have introduced a bias as the presence of internationally renowned experts in the group could have influenced some exchanges. The method used in the first round involved both translating the form and analyzing the content of the items. It would have been clearer to first conduct a proper translation, followed by the adaptation of the criteria in a second phase. Furthermore, a joint testing effort on a few recommendations to determine whether the experts had the same understanding of the criteria would have also strengthened this work. The over-representation of general practitioners among the experts does not seem to have had an impact on the results since the expert’s specialty was not a significant variable in the different opinions expressed during the process.

Consensus was reached on all items after three rounds, although some reserves, similar to those found in the original study remained: First, some experts felt that all medical decisions should be shared and that there is no need to suggest some recommendations more than others, as is suggested in Criterion 8. Since current CPGs have shown to be slightly favorable to SDM [9, 10], “flagging those recommendations for which incorporating patient preferences is urgent” [23] seems like a relevant step, which can be reassessed as CPGs evolve. Second, an expert underlined that including data on absolute and relative risk might confuse healthcare professionals about individual and population risk.

The only new criterion added to the original list recommends including patient representatives on the CPG panel. This measure was mentioned as a prerequisite for the integration of patient preferences in CPGs in Van der Weijden et al.’s article [23]. It is also recommended by AGREE II [30] and by the Guidelines International Network and the Institute Of Medicine [20].

According to our experts, the tool is to be presented as a checklist of ideas, which can each be applied to a CPG and not as an exhaustive list of compulsory items. A simple three-level scoring system marking each criterion as “present,” “partially present,” or “absent” was chosen over the initial binary option to allow more subtle evaluations while ensuring its ease of use.

This assessment tool does not fit into the usual strategy which consists of proposing to experts and policy decision-makers’ ways to facilitate the implementation of SDM in CPGs. In these strategies, the shared medical decision researcher plays a relatively minor role, proposing general rules upstream but without playing an active role in creating each of them. The vision of this tool is, in the long run, to take an active approach to this topic by allowing researchers, and those generally concerned with SDM, to carry out evaluations of CPGs and potentially directly target those with poor results. This could also lead to a dynamic like that of benchmarking which allows comparing recommendations between learned societies of the same or different countries. The evolution of this score as recommendations evolve will also have an educational aspect for editors.

These criteria have been developed with the aim of being applicable to all CPGs, regardless of their topic. This explains the broad scope of each criterion on elements that will be present in most CPGs.

This work is not however a validated measurement tool. The original items were described as “potential good ideas,” and this work will contribute to reinforce their value and, as participants pointed out, is part of a dynamic process. It should be evaluated and improved over time. The next necessary step is its beta-testing by other experts in concrete situations. A test will be organized during the next French symposium on SDM in 2025 to evaluate the items, scoring method, and reproducibility with the help of different French-speaking experts. To do this, we will select CPGs on a primary care situation: a screening method and/or a cardiovascular risk factor. Ten or so French-language recommendations on the chosen topic will then be analyzed by different groups of international French-language experts using the beta-testing tool, and the results of these groups will then be compared.

The main advantage of developing an evaluation tool is to enable guideline publishers to assess the effectiveness of their tools in this respect. Evaluation has a stronger incentive connotation than a list of recommendations and proposals, which are solely intended to be informative. Furthermore, evaluation allows for comparison between recommendations, which has more of a benchmarking logic. In practice, this will allow people who intervene in shared medical decisions, whether researchers, associations, or other stakeholders, to evaluate one or more recommendations. This evaluation can thus be used in discussion with those responsible for the design of the CPG to objectivize the presence or not of the SDM. Furthermore, it will be possible to classify recommendations according to this evaluation to broadly inform participants and patients of the resources available to better include patients in the choice. If this is the case, it is rational to think that the learned societies in charge of designing CPG will work to take them into account more to improve their ranking.

However, the temptation to perfect their validity should not overrun the urgency to implement these strategies in existing and upcoming CPGs.

The potential scope of this tool should not make us forget the potential barriers to its dissemination: First, it is in French, but it could be translated in the future. Though its use does not require many resources and remains simple, it will need to be supported by an institution. It will indeed be necessary to make it known, to promote its use, and to convince stakeholders and healthcare policy decision-makers of its interest as well as that of SDM. This work was presented twice at the international SDM conference in oral communication (2022 and 2024) [31], showing the community’s interest in it. The next steps can take place once the tool has been validated and published.

6. Conclusion

This tool is the first to formalize the assessment of SDM in CPGs continuing the work of Van der Weijden et al. [23]. It provides researchers and institutional stakeholders with a simple tool consisting of 17 objective evaluation criteria, enabling work on CPGs, both in terms of improving each individual CPG and also facilitating broader efforts of comparison and benchmarking, which are powerful drivers of change. It could be translated into other languages to further expand the scope of comparisons.

If the tool’s formative approach is endorsed by CPG developers and researchers, it could rapidly contribute to develop patient-centered recommendations and thus help implement a culture of SDM in French-language CPGs. This acculturation of patients and physicians remains fundamental to implement SDM in routine medical practice. To achieve this, it is essential that innovative and collaborative international projects like this one continue to be developed.

By providing the scientific and public communities with a unique, transcultural tool for evaluating CPGs in relation to SDM, this work aims to offer a rallying point for various stakeholders and foster collaboration, with the goal of producing more significant and impactful efforts to integrate SDM into CPGs.

Disclosure

Most of the experts in this study were healthcare professionals and researchers in the SDM area. The design of the study, its organization, and the interpretation of the data were entirely managed by them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors of this study did not receive any funding for its organization; it was carried out as part of their academic duties.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.