Social Prescribing for Children and Youth: A Scoping Review

Abstract

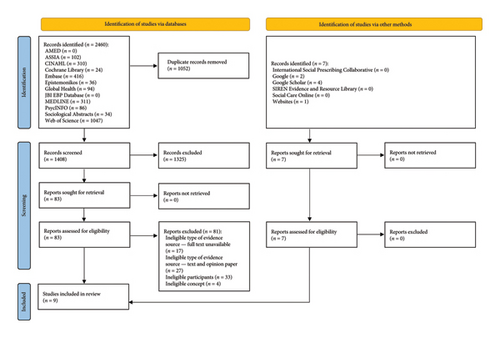

Social prescribing is gaining traction globally, with over 30 countries involved in the social prescribing movement. This holistic approach to health and well-being is relevant to all ages, but it is especially important for children and youth. While this population has largely been neglected in social prescribing efforts, several evaluations of social prescribing programs specifically targeting this population have emerged in recent years, which calls for a review of the evidence on this topic. Thus, the objective of this scoping review was to map the evidence on the use of social prescribing for children and youth. This review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished literature via 12 databases, Google, Google Scholar, Social Care Online, SIREN Evidence and Resource Library, websites of social prescribing organizations and networks, and a request for evidence sources to members of the International Social Prescribing Collaborative. No language or date restrictions were placed on the search. Two independent reviewers performed title and abstract screening, retrieval and assessment of full-text evidence sources, and data extraction. Data analysis consisted of basic descriptive analysis. Nine studies met the inclusion criteria, including three mixed methods studies, two rapid evidence reviews, two qualitative studies, one uncontrolled before-and-after study, and one randomized clinical trial. All studies were published between 2020 and 2024. Evidently, social prescribing for children and youth is still in its infancy, with an evidence base that is limited in both quantity and quality. However, the existing evidence is promising, offering a starting point to build a robust evidence base, which calls for research and practice advancements in social prescribing for children and youth.

1. Introduction

Social prescribing is “a means for trusted individuals in clinical and community settings to identify that a person has nonmedical, health-related social needs and to subsequently connect them to nonclinical supports and services within the community by coproducing a social prescription–a nonmedical prescription, to improve health and wellbeing and to strengthen community connections” ([1], p. 9). Social prescribing moves care upstream to address the nonmedical factors that determine the vast majority of health and well-being [2, 3]. It shifts the conversation from “what is the matter with you” to “what matters to you” [1]. By moving the locus of control from the provider of care to the recipient of said care, social prescribing aims to build self-determination by fostering autonomy (the need to feel control over life and decisions), relatedness (the need to have meaningful relationships and to feel a sense of belonging), competence (the ability to influence outcomes and to be capable and effective), and beneficence (the ability to give and to make a positive impact on others) [3]. Social prescribing not only improves health and well-being but also reduces healthcare demand and costs [2–10]. Given the potential of social prescribing to support health system transformation, this holistic approach to health and well-being has been integrated into practice in over 30 countries [1–3], and this number continues to grow.

While social prescribing is relevant to all ages, it is especially important for children and youth [11–14]. Children and youth are particularly vulnerable to the effects of the social determinants of health and health inequities [15]. As a tool to intervene on the downstream manifestations of these social conditions [1], social prescribing is a key part of giving children and youth the best start in life [16] and has the potential to be a lifechanging intervention for this population [17]. What’s more, it is widely accepted that intervening at this stage of life has the greatest impact on health and well-being over the life course [18]. As Frederick Douglass once said, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men” ([19], p. 1). Despite the clear rationale to target children and youth in social prescribing efforts, this population has largely been neglected in social prescribing research, policy, and practice, with adults receiving most of the attention [11–14]. With calls from experts to build the evidence base around social prescribing for children and youth [11], several evaluations of social prescribing programs specifically targeting this population have emerged in recent years. Therefore, a review of the evidence on this topic would be most valuable.

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE (Ovid), JBI EBP Database (Ovid), Cochrane Library, Google, and Google Scholar was conducted. A limited number of current and underway evidence reviews on social prescribing for children and youth were found [20–25], albeit with a specific focus on mental health [21–25] and restrictions on language [21–24], date [20], type of participants [20, 24, 25], type of social prescribing [20–23], and type of context [20]. Notably, no evidence reviews with an aim to comprehensively map the evidence on social prescribing for children and youth were found. To address this gap in the literature, there is a need for a review of the evidence that is not solely focused on mental health or restricted by language, date, participants, concept, or context. Additionally, now that there are internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing [1], there is an opportunity to use the operational definition to develop inclusion and exclusion criteria and to build the search strategy.

Given that scoping reviews are conducted to determine the scope of a body of literature on a particular topic [26–29] and are particularly useful for reviewing evidence in emerging fields or topics and for addressing broad review questions [26–28], this was deemed to be the most appropriate method to map the evidence on social prescribing for children and youth. Thus, a scoping review of the evidence was conducted.

The objective of this scoping review was to map the evidence on the use of social prescribing for children and youth. We also aimed to discuss implications for research and practice.

1.1. Review Questions

- 1.

What evidence exists on the use of social prescribing for children and youth?

- 2.

What are the knowledge gaps in the evidence base around the use of social prescribing for children and youth?

1.2. Eligibility Criteria

1.2.1. Participants

This review considered evidence sources with participants who were children and youth (≤ 25 years of age). Evidence sources with participants who were not children and youth (> 25 years of age) were excluded. This age cutoff aligns with other reviews on this topic [20, 22–25]. We excluded evidence sources with participants who bridged this age cutoff (e.g., ≥ 18 years of age) when there was no separation of children and youth from adults. Additionally, participants had to be children and youth rather than, for example, families, parents, guardians, or caregivers. Finally, to ensure that the review would be as comprehensive as possible, only the participants in the social prescribing program had to be children and youth, not necessarily the participants in the study (e.g., study on frontline staff involved in social prescribing for children and youth).

1.2.2. Concept

This review considered evidence sources that explored a concept that meets the following operational definition of social prescribing, even if it was not labeled social prescribing:

- •

Condition 1: Identifier identifies that person has nonmedical, health-related social needs (e.g., issues with housing, food, employment, income, social support)

- •

Condition 2: Identifier connects person to nonclinical supports and services within the community by coproducing a nonmedical prescription

- •

Condition 3: Identifier refers person to connector

- •

Condition 4: Connector connects person to nonclinical supports and services within the community by coproducing a nonmedical prescription ([1], p. 9).

Evidence sources that explored a concept that does not meet this definition were excluded. Notably, we excluded signposting, defined as “the provision of general resource lists or referral without ongoing follow-up” ([3], p. 2), since it is seen as being distinct from social prescribing [1, 3].

1.2.3. Context

This review considered evidence sources from any context, including country and setting, which reflects the global nature of the social prescribing movement and the fact that this complex intervention can take place in clinical and community settings.

1.2.4. Types of Evidence Sources

This review considered both published and unpublished literature. Evidence sources with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods study designs were considered. In addition to primary research, this review considered reviews (e.g., scoping reviews, systematic reviews) and meta-analyses, theses and dissertations, and reports (e.g., research reports, evaluation reports). Evidence sources without full text (e.g., conference abstracts), text and opinion papers (e.g., commentaries, editorials, letters to the editor, viewpoints), and protocols were excluded.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [27] and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [30]. We followed an a priori protocol, which was registered on Open Science Framework (osf.io/xhymv) and published in a peer-reviewed journal [31].

2.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished literature. An initial limited search of MEDLINE (Ovid) and CINAHL (EBSCO) was undertaken to identify evidence sources on the topic. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant evidence sources, and the index terms used to describe the evidence sources were used to develop a full search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid). The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was adapted for each information source. The full search strategy is provided in Appendix I. The reference lists of all included evidence sources were screened for additional evidence sources. No language or date restrictions were placed on the search. All non-English language evidence sources were to be translated into English through DeepL Translator (DeepL SE, Cologne, Germany). The final search was conducted on February 8, 2024.

The databases that were searched included MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), AMED (Ovid), ASSIA (ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Global Health (Ovid), Web of Science (Clarivate), Epistemonikos, JBI EBP Database (Ovid), and Cochrane Library. Sources of gray literature that were searched included Google, Google Scholar, Social Care Online (Social Care Institute for Excellence), SIREN Evidence and Resource Library (Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network), and websites of social prescribing organizations and networks, including the Social Prescribing Network, the Social Prescribing Youth Network, the National Academy for Social Prescribing, and the Canadian Institute for Social Prescribing. Additionally, a request for evidence sources was sent out to members of the International Social Prescribing Collaborative.

2.2. Evidence Source Selection

Following the search, all identified evidence sources were collated and imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates removed. A pilot test was done with 10% of evidence sources to ensure consistency across reviewers (CM, EC, and XAZ). Subsequently, titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (CM and either EC or XAZ) for assessment against the inclusion criteria for this review. Potentially relevant evidence sources were retrieved in full, imported into Covidence, and assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers (CM and either EC or XAZ). Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data were extracted from evidence sources included in the scoping review by two independent reviewers (CM and either EC or XAZ) using a data extraction tool. The tool was created by the research team during the development of the a priori protocol [31] to collect specific details about the objective, participants, concept, context, methods, and key findings relevant to the review questions. During data extraction, the tool was refined to include study type and label. The final tool is presented in Appendix II. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion. It was not necessary to contact the authors of evidence sources for missing or additional data.

2.4. Data Analysis and Presentation

Data analysis consisted of basic descriptive analysis. As per the a priori protocol [31], the results of this review are presented in a narrative summary along with three tables and one figure.

3. Results

3.1. Study Inclusion

A total of 2460 evidence sources were identified through database searches. After 1052 duplicates were removed, 1408 evidence sources were screened based on titles and abstracts. A total of 1325 evidence sources were excluded at this stage. The full texts of 83 evidence sources were assessed for eligibility. A total of 81 evidence sources were excluded at this stage. Reasons for exclusion included the following: ineligible participants (i.e., not children and youth) (n = 33); ineligible type of evidence source—text and opinion paper (i.e., commentary, editorial, letter to the editor, viewpoint) (n = 27); ineligible type of evidence source—full text unavailable (i.e., conference abstract) (n = 17); and ineligible concept (i.e., not social prescribing) (n = 4). A total of two evidence sources met the inclusion criteria. Gray literature searches yielded another seven evidence sources from Google Scholar (n = 4), Google (n = 2), and the National Academy for Social Prescribing website (n = 1). Altogether, nine evidence sources were included in the review. The results of the search and the evidence source inclusion process are presented in Figure 1.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. All nine studies were published between 2020 and 2024 [21, 23, 32–38], with most published in 2023 (n = 5). There were three mixed methods studies (33%) [32, 34, 36], two rapid evidence reviews (22%) [21, 23], two qualitative studies (22%) [35, 38], one uncontrolled before-and-after study (11%) [33], and one randomized clinical trial (11%) [37]. Most studies labeled the concept as “social prescribing” [21, 23, 32–36, 38], while one study labeled it as “social needs navigation” [37]. Out of the seven primary research studies, five studies aimed to evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth [32–34, 36, 37]. The study details are presented in Table 2. The remaining two primary research studies examined the perspectives of frontline staff involved in social prescribing for children and youth. Hayes et al. [35] aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators to social prescribing from the perspective of frontline staff working with children and youth to improve mental health and well-being, and Farina et al. [38] aimed to describe the role played by link workers in social prescribing for children and youth. The study details are presented in Table 3. Both reviews aimed to explore the impact of social prescribing on the mental health and well-being of children and youth [21, 23]. Hayes et al. [21] published the first review in 2020. After searching four databases up to September 2019 and sending out requests for the gray literature, they found no studies for inclusion. Hayes et al. [23] subsequently published an updated review in 2023. After searching four databases up to February 2022, they found four studies for inclusion. Two of these four studies met the inclusion criteria for our review [32, 33]. The other two studies were excluded for the following reason: ineligible type of evidence source—text and opinion paper. To address the partial overlap between the studies and reviews included in our review, we only discuss the studies, not the reviews.

| Study | Type | Label | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. [32] | Mixed methods study | Social prescribing | To evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth |

| Hayes et al. [21] | Rapid evidence review | Social prescribing | To explore the impact of social prescribing on the mental health and well-being of children and youth |

| Brettell et al. [33] | Uncontrolled before-and-after study | Social prescribing | To evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth |

| Charlton [34] | Mixed methods study | Social prescribing | To evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth |

| Hayes et al. [35] | Qualitative study | Social prescribing | To explore the barriers and facilitators to social prescribing for children and youth |

| Polley et al. [36] | Mixed methods study | Social prescribing | To evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth |

| Rucker et al. [37] | Randomized clinical trial | Social needs navigation | To evaluate a social prescribing program for children and youth |

| Hayes et al. [23] | Rapid evidence review | Social prescribing | To explore the impact of social prescribing on the mental health and well-being of children and youth |

| Farina et al. [38] | Qualitative study | Social prescribing | To describe the role played by link workers in social prescribing for children and youth |

| Study | Participant details | Context | Program details | Study methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bertotti et al. [32] |

|

|

Pilot took place between September 2018–September 2020. Most common referral sources = friends and family (18.9%); GP practices (18.0%); schools (17.2%); mental health services (10.7%); social care (10.7%). Most common reason for referral = mental health and well-being (40.1%). Sessions were face-to-face and virtual. On average, service users completed 4 to 5 (maximum 8) 1-h sessions with link worker. Length of support ranged from 12 weeks to 12 months. Sessions typically took place every 1 to 2 weeks. Service users received wide variety of social prescriptions (e.g., social activities, basic needs support, arts and culture programs, physical activities) |

|

|

| Brettell et al. [33] | Service users aged 16–25 |

|

Service users referred by GP, third-party professional, or self-referral upon being identified as struggling to cope with stress related to nonmedical issues. On average, service users engaged with well-being coordinator once per week. Sessions were face-to-face and virtual. Service users received wide variety of social prescriptions (e.g., social activities, basic needs support) | -Service user assessment tool (UCLA Loneliness Scale, ONS4, SWEMWBS, well-being wheel) upon entry to service and upon exit (January 2019–January 2020) |

|

| Charlton [34] |

|

|

Pilot took place between July 2022–June 2023. Referrals made by mental health clinicians to social prescriber via low mental health needs pathway and moderate to severe mental health needs pathway. Most common reasons for referral = anxiety (33.6%) and low mood (15.0%). Average wait time = 13 days (range = 0–78 days). Sessions were face-to-face and virtual. Average length of support = 96 days. Out of 107 referrals, 56 service users (52.3%) engaged with service |

|

|

| Polley et al. [36] |

|

|

Service launched in February 2021. Link worker received referrals from GPs at five GP practices and via website (e.g., self-referral, schools, ED). Most common reason for referral = mental health and well-being (55.0%). Service users completed 1-h sessions (maximum 6) with link worker. Sessions were face-to-face and virtual. Service users received wide variety of social prescriptions (e.g., social activities, basic needs support, arts and culture programs, physical activities). On average, service users received 5.22 social prescriptions |

|

|

| Rucker et al. [37] |

|

|

Between July 2017–August 2019, adolescents randomized to intervention and control groups. Both groups completed social needs survey. Intervention group received in-person, risk-tailored social needs navigation. Control group received preprinted resource guide |

|

|

- Note: ONS4 = National Statistics Personal Wellbeing Measure.

- Abbreviations: aOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, ED = emergency department, GP = general practitioner, SD = standard deviation; SROI = social return on investment, SWEMWBS = Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, WEMWBS = Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale.

| Study | Participant details | Context | Study methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayes, et al. [35] | Link workers (n = 11) and individuals involved in facilitating social prescribing for children and youth (n = 9) at multiple organizations | United Kingdom | Interviews |

|

| Farina et al. [38] | Link workers (n = 4) involved in social prescribing for children and youth at one specific organization | United Kingdom | Interviews |

|

- Abbreviation: GP = general practitioner.

3.3. Review Findings

3.3.1. Participant Details

Service user characteristics were discussed in all six studies that described a social prescribing program for children and youth [32–34, 36–38]. All six studies reported on age, with service users ranging in age from 7 to 25 years. Programs mainly served youth (15–25 years of age), with most service users being 15–17 years of age and very few service users being children (0–14 years of age). Four studies reported on ethnicity, revealing that programs were mixed in terms of predominantly serving white [32, 34] or ethnic minority groups [36, 37]. The same four studies also reported on sex and gender, indicating that there were slightly more females than males across all programs, with limited representation from gender diverse people [32, 34, 36, 37]. Two studies reported on sexual orientation, with most service users identifying as heterosexual [34, 37].

As for the two studies involving frontline staff, one of them included link workers (n = 11) and individuals involved in facilitating social prescribing for children and youth (n = 9) at multiple organizations [35], while the other included link workers (n = 4) involved in social prescribing for children and youth at one specific organization [38].

3.3.2. Context

Most studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 6) [32–36, 38], while one study was conducted in the United States (n = 1) [37].

All six studies that described a social prescribing program for children and youth reported on the program location [32–34, 36–38]. Programs were based in a wide range of clinical and community settings, including charitable organizations [32, 33, 38], general practitioner (GP) practices [38], emergency departments (EDs) [37], a mental health clinic [34], a youth clinic [36], and a school [38].

3.3.3. Program Details

To varying degrees, program details were discussed in all six studies that described a social prescribing program for children and youth [32–34, 36–38].

The process of identifying needs was mentioned in five studies [32–34, 36, 37]. Four programs identified needs through conversation [32–34, 36], while one program used a survey [37].

All six studies detailed various aspects of the referral process [32–34, 36–38]. Four programs had multiple referral sources [32, 33, 36, 38], while two programs had one single referral source [34, 37]. The most common referral sources were GP practices [32, 33, 36, 38], self-referral [33, 36, 38], schools [32, 36, 38], mental health services [32, 34], EDs [36, 37], and friends and family [32, 38]. Four programs found that the most common reason for referral was mental health and well-being [32–34, 36]. Charlton [34] reported that service users waited an average of 13 days (range = 0–78 days) after being referred. They also examined service user engagement, finding that out of 107 referrals, 56 service users (52.3%) engaged with the service.

All programs had a connector [32–34, 36–38]. Across the six studies, several different terms were used for the connector role, including link worker [32, 36, 38], social prescriber [34], well-being coordinator [33], and social navigator [37].

All six studies detailed various aspects of the sessions [32–34, 36–38]. One program only offered face-to-face sessions [37], while four programs offered a mix of face-to-face and virtual sessions [32–34, 36], with virtual sessions often being instated due to the COVID-19 pandemic [32, 36]. The number of sessions was documented by four studies, with variation both within and across programs, ranging from 1 to 12 sessions [32, 36–38]. Two studies reported that the length of sessions was an average of 1 hour [32, 36]. The length of support was documented by three studies, with variation both within and across programs, ranging from 12 weeks to 12 months [32–34]. Two studies reported that the frequency of sessions was an average of 1 to 2 weeks [32, 33].

Three studies shared the details about the social prescriptions [32, 33, 36]. The most common types of social prescriptions were social activities [32, 33, 36], basic needs support [32, 33, 36], arts and culture programs [32, 36], and physical activities [32, 36]. Polley et al. [36] reported that service users received an average of 5.22 social prescriptions.

Lastly, most evaluations focused solely on social prescribing [32–34, 36], while one evaluation compared social prescribing (intervention group) to signposting (control group) [37].

3.3.4. Study Methods

Participant and program details were gathered by collecting service user demographic data [32, 34, 36, 37] and service data [32, 34, 36].

Service user health and well-being outcomes were examined through pre- and postsurveys [32–34, 36]. Across programs, there was no consistency with the timing of these assessments, occurring upon entry to the service and upon exit [33] and at baseline and an average of 13 days (range = 1–69 days) [36], six weeks [34], and six months [32]. Measures included personal well-being with the Office for National Statistics Personal Wellbeing Measure (ONS4) [32, 33, 36], mental well-being with the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) [34] and Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) [32, 33], loneliness with the indirect (UCLA Loneliness Scale) [33] and direct (single-item) measure [32], physical activity [32], social capital [32], and perceived level of required support [33].

Healthcare and community resource use and cost were examined by Bertotti et al. [32] through a cost–benefit analysis (social return on investment) and cost assessment of healthcare service use, and by Rucker et al. [37] through a chart review and follow-up calls to assess ED revisits and community resource use.

Lastly, service user and stakeholder experiences were explored through interviews [32, 34–36, 38], surveys [34, 36], and focus groups [32], with stakeholders typically consisting of connectors [32, 34–36, 38], providers [32, 34–36], family members [34, 36], program managers [34, 35], and representatives from the health system and community sector [32, 36].

3.3.5. Service User Health and Well-Being Outcomes

All three studies that examined personal well-being reported improvements [32, 33, 36], particularly for those with the lowest scores at baseline [32] and for those referred for nonmental health issues [36], with some findings reaching statistical significance [36]. Similarly, all three studies that examined mental well-being reported improvements [32–34], particularly for those with the lowest scores at baseline [32], with some findings reaching statistical significance [32]. Both studies that examined loneliness reported improvements [32, 33], particularly extreme feelings of loneliness [32]. Bertotti et al. [32] examined physical activity, reporting an increase in the proportion of physically active service users. They also examined social capital, reporting mixed findings. Brettell et al. [33] observed reductions in the perceived level of required support.

3.3.6. Healthcare and Community Resource Use and Cost

Bertotti et al. [32] reported a social return on investment of £1:£5.04, calculated by the difference between the financial value of outcomes (personal well-being, mental well-being, employment, volunteering, financial manageability, attending organized activities, fear of crime) and the financial value of inputs (cost of delivering service). They also collected self-reported data on healthcare service use at baseline and 3 months, revealing statistically significant reductions in GP consultations and ED visits, and a statistically nonsignificant reduction in hospital admissions. Rucker et al. [37] found that there was no difference between social prescribing (intervention group) and signposting (control group) in the number of ED revisits at 12 months but reported that social prescribing was associated with a statistically significant increase in community resource use, with social prescribing service users having higher odds of community resource use than signposting service users at 3 and 12 months.

3.3.7. Service User and Stakeholder Experiences

“I enjoyed being able to simply do art and crafts and try new things that felt enriching and fulfilling.”—Service user ([34], p. 29)

“I supported a young person who would not make eye contact or speak directly to me at the beginning. They only spoke through their parents. I supported them to start learning to play a musical instrument and we built our relationship from that. They are now happy to make eye contact and speak with me, which is a huge change.”—Connector ([34], p. 31)

“I arranged for a charity delivering sheep therapy to come out to meet a young person who has not engaged with anything in two years. Initially the young person did not want to get out of the car. But they did. And then within five minutes they were walking the sheep.”—Connector ([34], p. 29)

“I tried my best to be independent so I was going on my own and that morning I text him and I was like, ‘I can’t do it’. So he rang me and then he was like, ‘Oh I’m free this afternoon I’ll come with you’. So I met him here and he walked all the way down and that was really good, because it just put me in a more positive mind set when I got in there. And I did do it on my own, but the fact that he was just there, and I knew he was waiting outside for me, just made a massive difference.”—Service user ([32], p. 34)

“…for the first week, I couldn’t leave the room or their side. Now they go in and I go to a café nearby.”—Family member ([34], p. 32)

“This is not about saying that we don’t need (mental health services) or whoever anymore, but it’s about saying that we need to make sure that the people that are accessing those services are the ones that really need it, that can access it swiftly and effectively in a timely manner. And that actually for some people, a social prescription approach would be the absolute best and that’s enough.”—Health system official ([32], p. 29)

“I’ve worked in (mental health services) for 20 years and have been amazed how helpful the introduction of a social prescriber in our team has been! I received some support with a few incredibly complex young people on my caseload, whose lives have become incredibly constricted. Those young people are now getting out more, growing in confidence and engaging better with our mental health treatments.”—Provider ([34], p. 1)

“It’s given me the confidence that my child has the capability to do things, if they want to.”—Family member ([34], p. 33)

“One of the main differences it’s made to me as a practitioner is feeling less guilty when it comes to the young people we work with. It’s a horrible feeling to put them on a long waiting list for treatment. Having (connectors) takes that away. It’s just a really nice feeling to know that a young person can join other things and have that sense of belonging in a community….”—Provider ([34], p. 36)

“I thought to myself, I’m working with adults, and I saw that a lot of the issues people live with were because of what they’d been through while they were younger.”—Connector ([38], p. 5)

“It comes from just communicating with different kind of services in the city, to find out what there is really, and build the relationships, because when we support someone to go to a service, we don’t just want to say, here’s the information off you go, we want to kind of build that relationship between that young person and that service.”—Connector ([38], p. 8)

“So that’s sort of like the main problem with my situation which was like, trying to turn up and play a football session, which, (my connector) took me to see how it was and it was the sort of thing that I’d like to do but it was just too far away and that was like the main reason why I chose not to do it.”—Service user ([32], p. 35)

“When we first started, we said we were going to be dealing with young people on the mild spectrum, who might be finding it a bit difficult to gain friendships or not going out. But now I’m finding that the young people referred in are people with more moderate to complex needs, where they are showing signs or are speaking of showing signs of being suicidal.”—Connector ([34], p. 38)

“Both misunderstanding and misuse. I just don’t think they realize the remit of the role. And then other times, I think they do realize, but they’re just hopeful that we would be able to fill the gap where there are other services, because they’re aware that the next services up from our threshold are really difficult to access, massive, long waiting lists and underfunded. So sometimes they just appear to be hopeful that we can do something, even if it’s not the perfect fit.”—Connector ([38], p. 9)

“Yeah sometimes parents can sort of take over. Or they might not think it’s the right support. I’ve got some families where parents want their child to be doing loads of activities and the children just aren’t interested which can obviously be a bit of a barrier and a bit of family relationship work going on to try and help families understand what each other wants.”—Connector ([32], p. 29)

“So we ended up having these clandestine meetings where he’d be hiding in the bathroom talking to me, after we’d arranged it by text, to arrange a time when he would be free to talk. I’d arranged my schedule around him because, normally, I just did certain GP surgeries on certain days, but because this was so unusual, I thought, ‘If you only get half an hour of privacy a week, I’ll just do that, whatever’.”—Connector ([36], p. 32)

Additional issues often experienced by stakeholders include community capacity to “fill” social prescriptions (e.g., lack of funding for community sector) [32, 35], provider engagement (e.g., difficulty maintaining visibility) [32, 35], connector caseload pressure and stress (e.g., burden of dealing with complex cases) [35, 36], connector supervision and support (e.g., lack of supervision and peer support) [35, 36], service user readiness to build trust with the connector and connect with community assets (e.g., service user apprehensiveness about interacting with people) [36, 38], monitoring and evaluation (e.g., difficulty finding appropriate measures) [34, 35], and the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., significant shift in the delivery of sessions and social prescriptions) [32, 36].

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to comprehensively map the evidence on social prescribing for children and youth. With nine studies included in this review, we uncovered limited, albeit promising, evidence on this topic and notable knowledge gaps in the evidence base.

Both published [33, 35, 37, 38] and unpublished literature [21, 23, 32, 34, 36] was found, confirming that much of the social prescribing literature is unpublished [39]. As noted by Zurynski et al. [10], by nature of the fact that social prescribing programs are run by healthcare and community service organizations, evaluations tend to be disseminated through nonacademic avenues due to competing priorities and limited capacity. Consistent with previous reviews on this topic [21, 23], we discovered that social prescribing for children and youth is still in its infancy, with only a handful of studies on this topic and all of them published within the past 4 years [32–38]. We located quantitative [33, 37], qualitative [35, 38], and mixed methods studies [32, 34, 36], reflecting the diversity of approaches that are needed to investigate this complex intervention [10]. By using the internationally accepted operational definition of social prescribing [1], we were able to search for studies that explored the concept of social prescribing regardless of whether it was labeled as such, allowing us to locate eight studies from the United Kingdom that labeled it as “social prescribing” [21, 23, 32–36, 38] and one study from the United States that labeled it as “social needs navigation” [37]. Studies evaluated social prescribing programs for children and youth [32–34, 36, 37] and examined the perspectives of frontline staff involved in this work [35, 38], offering a starting point to build a robust evidence base.

Given that programs mainly served youth (15–25 years of age) [32–34, 36–38], we note that evidence is particularly limited for children (0–14 years of age). Recognizing the importance of health equity in social prescribing [1], it is worth noting the limited representation from structurally oppressed groups [32, 34, 36, 37], which is consistent with adult social prescribing [40]. This finding points to Tudor Hart’s Inverse Care Law [41], in that the availability of social prescribing appears to be inversely associated with the level of need. Most studies took place in the United Kingdom [32–36, 38], signaling the need for further development of efforts in this leading nation alongside expansion to other parts of the world, so as to reflect global developments in social prescribing [2, 3]. We found that social prescribing looked different both across and within programs [32–34, 36–38]. We posit that this heterogeneity is an inherent quality of this complex intervention that must be taken into account in building a robust evidence base by understanding what works, for whom, and in what circumstances.

Studies reported mostly positive effects of social prescribing [32–34, 36, 37]. We found that quantitative investigations predominantly reported improvements in service user health and well-being, including personal well-being [32, 33, 36], mental well-being [32–34], loneliness [32, 33], physical activity [32], and perceived level of required support [33], often using validated measures [32–34, 36]. While Bertotti et al. [32] reported mixed findings for social capital, we note that this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which likely impacted this measure. We also found that quantitative investigations predominantly reported positive effects on healthcare and community resource use and cost. Bertotti et al. [32] reported reductions in GP consultations, ED visits, and hospital admissions at 3 months and calculated a social return on investment of £1:£5.04, which exceeds the mean of £1:£2.30 for adult social prescribing [42]. Rucker et al. [37] reported increased community resource use with social prescribing and higher odds of community resource use than signposting at 3 and 12 months, indicating that social prescribing is likely more effective. While there was no difference between social prescribing and signposting in the number of ED revisits at 12 months, Rucker et al. [37] noted that the decision to use the ED is often multifactorial and that the benefits of social prescribing to ED visits may not be realized in a short time frame. In comparison, reviews of adult social prescribing typically report mostly positive effects on service user health and well-being and mostly mixed effects on healthcare and community resource use and cost [4, 7, 43–48].

We found that qualitative investigations predominantly reported positive service user experiences, including increased awareness and engagement with community assets and enhanced health and well-being [32, 34, 36], as well as complex concepts that are hard to quantify, including service user empowerment and increased confidence and sense of autonomy [32, 34, 35, 38]. Similarly, we found that qualitative investigations predominantly reported positive stakeholder experiences [32, 34, 36], in that they not only felt that social prescribing benefited service users [32, 34–36] but also themselves [34–36]. Along with successes, we came across several facilitators. Firstly, we took note of the importance of relationships, including the relationship that is built between the service user and the connector [32, 34, 36, 38], the relationship that is built between the service user and community organization via the connecting role of the connector [32, 34–36, 38], and the relationships that are built between the connector and community organizations and other stakeholders via the networking role of the connector [32, 34–36, 38]. Secondly, we took note of the importance of creating a welcoming and accessible service for service users [32, 35, 36, 38]. Thirdly, we took note of key qualities of the connector, including being motivated to help children and youth and having specific knowledge and skills to engage with this population [34, 35, 38]. These successes and facilitators resemble those of adult social prescribing [10, 49]. Similarly, we discovered challenges and barriers [32, 34–36, 38] that resemble those of adult social prescribing [10, 49, 50], including cost and transportation [32, 34, 35], community capacity to “fill” social prescriptions [32, 35], provider engagement [32, 35], connector caseload pressure and stress [35, 36], connector supervision and support [35, 36], service user readiness to build trust with the connector and connect with community assets [36, 38], monitoring and evaluation [34, 35], and the COVID-19 pandemic [32, 36]. The similarities with adult social prescribing stop here, however, as the evidence base paints a picture of a complex intervention that is even more complex when offered to children and youth. Indeed, one of the most common challenges experienced by stakeholders pertained to the added complexities of social prescribing for this population compared to adults [32, 35, 36], including the need to navigate the involvement of family members [32, 35, 36] and manage confidentiality [32, 36].

As the most common reason for referral [32–34, 36], mental health was a major focus of evaluations. Interestingly, although social prescribing had positive impacts on mental well-being [32–34] and was praised for filling a gap in mental health support [32, 34, 36], the most common issues experienced by stakeholders were inappropriate referrals and complex mental health needs [32, 34–36, 38], stemming from misunderstanding and misuse of the service as a “gap filler” for an overburdened mental health system [38]. This finding points to the benefits of social prescribing for low mental health needs while bringing into question its appropriateness for moderate to severe mental health needs.

From a health quality standpoint, the evidence base around social prescribing for children and youth can be examined through the lens of the Quadruple Aim—an internationally recognized framework for optimizing health system performance [51]. The evidence suggests that social prescribing for children and youth may support all four dimensions of the Quadruple Aim by enhancing service user experience, enhancing provider experience, reducing healthcare costs, and improving population health [32–38]. This warrants further investigation, with consideration of whether social prescribing for children and youth may also advance health equity, which is the fifth aim in the Quintuple Aim—a newly expanded version of the Quadruple Aim that recognizes the need to advance health equity [52]. Given the growing global healthcare crisis [53], the fact that social prescribing for children and youth shows promise in supporting the achievement of high-quality care within the dimensions of a widely accepted framework for health system improvement means it is worth exploring further.

The findings presented in this review point to a number of ethical matters surrounding social prescribing for children and youth. This includes the scope of practice of the connector and the extent to which it is clearly outlined and adhered to, the need for the connector to navigate the involvement of family members and manage confidentiality, and the responsibility of the field to uphold distributive justice by targeting efforts toward structurally oppressed groups so as to mitigate—rather than perpetuate or exacerbate—health inequities, to name but a few.

Although the quality of included studies was not assessed, we observed that the evidence base is characterized by weaknesses and limitations in study design and reporting, including small sample sizes, lack of control groups, short and inconsistent follow-up durations, loss to follow-up, lack of standardized measures, lack of statistical analysis, and missing information, including participant, program, and study details, which is consistent with criticisms that have been made in reviews of adult social prescribing [4, 7, 43–48]. Therefore, we stress that findings must be interpreted with caution.

4.1. Limitations

This review has limitations to note. Although every effort was made to conduct a comprehensive search, it is possible that relevant studies were missed. To maintain a clear focus, we limited the scope of this review to one specific type of pediatric social prescribing, where children and youth are the participants, meaning we did not include studies where families, parents, guardians, or caregivers were the participants, although this was something we came across during our search. Particularly with social prescribing for children, it is common to take a family approach, with many examples of this in the literature. For example, Gottlieb et al. [54] conducted a randomized clinical trial in pediatric care, where caregivers either received social prescribing (intervention group) or signposting (control group). Compared with the control group, caregivers in the intervention group reported significantly greater reduction in social needs and significantly greater improvement in child health status. A secondary analysis revealed that children in the intervention group were equally likely to visit the ED but 69% less likely to be hospitalized compared with the control group [55].

4.2. Implications for Practice

The findings presented in this review offer important insights for practice. Although we are not yet able to draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of social prescribing for children and youth, the evidence suggests that it may be beneficial, which calls for increased experimentation with this complex intervention in practice, with evaluation built in from the outset. This applies to all children and youth in all countries, but especially children, structurally oppressed groups, and countries outside of the United Kingdom. However, we offer a word of caution regarding the appropriateness of this service for moderate to severe mental health needs. By outlining what social prescribing looks like for this population, key barriers and facilitators, and ethical considerations, the findings of this review can serve as a helpful roadmap in guiding the delivery of this complex intervention in practice.

4.3. Implications for Research

The findings presented in this review also offer important insights for research. Given the limited evidence base around social prescribing for children and youth, there is a need for more research on this topic, both quantitative and qualitative, to understand what works, for whom, and in what circumstances. As part of this work, we need to develop a better understanding of the role of social prescribing for children and youth in supporting not only the Quadruple Aim [51] but also the Quintuple Aim [52]; gain clarity on the role of social prescribing in supporting child and youth mental health; strengthen the evidence base around youth and countries in the United Kingdom while simultaneously filling notable gaps in evidence on children, structurally oppressed groups, and countries outside of the United Kingdom; and dive deeper into what social prescribing looks like for this population, key barriers and facilitators, and ethical considerations. To build a robust evidence base, not only does the quantity of evidence need to improve but also the quality of evidence by addressing the shortcomings in study design and reporting that have been identified in the current evidence base. More specifically, building on the recommendations made by Hayes et al. [23], there is a need for larger sample sizes; use of control groups; longer and more consistent follow-up durations; efforts to minimize loss to follow-up; development and use of standardized measures; statistical analysis, including means, standard deviations, and significance levels; and detailed reporting of key information, including participant, program, and study details.

This review also offers important insights for evidence reviews on social prescribing. Firstly, as the first review to do so, we have demonstrated the value of using the internationally accepted operational definition of social prescribing [1] to develop inclusion and exclusion criteria and to build the search strategy. Doing so ensured that this work aligns with current understanding of this concept. By using the operational definition, we were not only able to locate a relevant evidence source that is not labeled as social prescribing but also rule out multiple evidence sources that are erroneously labeled as social prescribing. Secondly, we have shown the importance of searching for both academic and gray literature on social prescribing. Thirdly, we have established the need for a review on another type of pediatric social prescribing, where families, parents, guardians, or caregivers are the participants, to complement this review.

5. Conclusion

In this review, we mapped the evidence on the use of social prescribing for children and youth. We found that there is limited evidence on this topic and notable knowledge gaps in the evidence base. It is apparent that social prescribing for children and youth is still in its infancy, with an evidence base that is limited in both quantity and quality. However, the existing evidence is promising, offering a starting point to build a robust evidence base. The time is now to bolster efforts to support research and practice advancements in social prescribing for children and youth.

Disclosure

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the University College London or the University of Toronto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing. E.C. and X.A.Z.: investigation and writing–review and editing. K.M. and C.G.: supervision and writing–review and editing. I.B. and R.A.: writing–review and editing. A.R.-W: methodology and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The authors received financial support from the University College London–University of Toronto Emerging Global Talents Fund for open access publishing of this article.

Acknowledgments

This report is independent research supported by the University College London–University of Toronto Emerging Global Talents Fund.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supporting Information.