Linking Up: The Impact of Transformational Leadership Approaches on a Social Prescribing LINK Children and Young People Service – A Qualitative Exploration

Abstract

Background: Poor mental health among children and young people (CYP) is a global issue, with one in seven affected. In the United Kingdom (UK) and abroad, social prescribing is emerging as a community-based, non-clinical method to address health inequalities. Link workers (LWs) play a pivotal role in this approach, and more research about the factors influencing their recruitment, retention, and job satisfaction is required.

Aim: This study explores the experiences of LWs working with CYP, focusing on service delivery, job satisfaction, career development, and retention, addressing a critical gap in research on LW roles and their influence on CYP care.

Method: This qualitative study employed semistructured, one-to-one interviews with 17 LWs and managers. These interviews were conducted between April 2023 and February 2024. Data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis framework, identifying key themes related to LW experiences and job satisfaction.

Findings: The findings highlight how a transformational leadership approach contributed to LW job satisfaction and retention, characterised by supportive leadership that promoted flexibility and autonomy, and continuous professional development (CPD) that enabled career progression.

Conclusion: Findings from this study established a unique conceptual model of LW job satisfaction and retention, which illustrates how transformational leadership fosters a creative, collaborative environment that supports flexibility, continuous development, and meaningful impact for LWs. This approach creates the conditions for sustainable services by promoting job satisfaction and retention, ensuring that LWs can consistently provide person-centred care to CYP and their families.

1. Introduction

Mental ill-health in children and young people (CYP) has risen globally as a result of health and social inequalities [1]. In particular, CYP have been negatively impacted by social inequalities and Covid-19 which has caused psychological distress for CYP and their families [2]. For example, extensive disruption in CYP’s lives is reported and many children have experienced a significant increase in mental health symptoms as a result [3, 4]. Subsequently, poor mental health in CYP is now an international concern with an estimated one in seven having been diagnosed with a mental health condition [5]. The impetus to stem the rising tide of health inequalities and identify systems that can help combat these effects is now a global priority [6]. As noted by the United Kingdom (UK) Marmot Review on health inequalities [7] a disproportionate number of CYP remain living in poverty and facing health inequalities. The Good Childhood Report [8] indicated that 25.2% of 15-year-olds across 27 European countries now experience low life satisfaction [8]. Subsequently, there are increasing calls for policy makers to intensify efforts, reduce inequalities, and empower CYP to access services and support at the right time for them [8, 9].

It is reported that early intervention and community-based approaches, co-producing solutions with CYP, and improving school culture could address poor mental health, creating a happier society [7, 10]. Building on community-based services could influence an increase in CYP self-confidence, develop self-esteem, and improve emotional well-being [10]. However, supporting CYP and their families is a complex issue and integrating services and taking a whole systems approach to supporting CYP is essential [11]. One distinctive area which is emerging in the UK to address the complexities is social prescribing. Increasingly, health and care providers are using non-clinical methods predicated on community asset–based approaches to help reduce the impact of health inequalities and promote resilient, healthy communities [12].

Social prescribing is a systems-based approach that enables a person to be referred by a health or care professional, to a Link Worker (LW) (or equivalent) for non-medical support within the community. Globally, social prescribing is gaining momentum as a person-centred approach that can support populations in most need [13]. A crucial aspect of the social prescription is the ‘well-being conversation’ that the LW facilitates with those who have been referred, to enable a discussion about ‘what matters to them’. This aligns with the Salutogenic model developed by Antonovosky in 1987 [14], which advocates for a non-pathogenic, strengths-based approach to supporting wellness. Salutogenic principles are predicated on person-centred approaches that are used by LWs to understand ‘what matters to a person’, rather than ‘what’s the matter with them’. It is the well-being conversation, and subsequent assessment, that uses person-centred approaches to enable the LWs to assess the individual’s needs, understand their goals, and refer them to a non-medical service [15].

It is reported that person-centred approaches used by LWs empower individuals to self-manage to take greater autonomy of their life decisions [16]. Recognition of the role of LWs in England (UK) in the National Health Service England (NHSE) Long Term Plan [16] influenced the funding and establishment of over 3000 LWs. Typically, LWs are employed as part of the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS) which was introduced by the UK Government across Primary Care Networks (PCNs) to complement the multi-disciplinary team and address population health needs at a place-based level in England. LWs within PCNs support the development of individual resilience and promote well-being across a range of age groups [17, 18]. Importantly, the therapeutic relationship engendered by LWs through the salutogenic person-centred approach is acknowledged to be beneficial for CYP [19]. In particular, children need someone who is empathic, genuine, and a good listener who can understand the individual’s context [20]. Sharing information between an LW and child through person-centred methods is essential to the success of the social prescription and emphasises the importance of a child-directed approach.

The person-centred, salutogenic principles used by LWs to understand what matters to an individual and support their needs also enhances job satisfaction for LWs [20] and can help support behaviour change that leads to supported self-management and reduction in mental health symptoms [21]. Evidence on the impact of the LW is increasing. For instance, Wildman and Wildman’s [22] quasi-experimental study indicated that the key factor influencing job satisfaction is the ability of the LW to empower individuals to manage their conditions more effectively. The LW role is varied, and others have reported that LWs can experience challenges which can impact on job satisfaction [23]. A significant factor that has been reported to influence LW job satisfaction is the discrepancy between job expectations and the complexities of their work [24]. The empowerment of individuals is therefore a key determinant in the perceived satisfaction with the LW role. Many LWs value the positive impact that they have on individuals’ lives, providing them with a great sense of role satisfaction [25]. However, while the majority of LWs perceive their role to be rewarding, the complexity and increasing caseloads of the people they support coupled with the lack of formal support infrastructure can lead to increased stress [26]. Unsurprisingly, reports suggest that LWs are susceptible to stress due to the limited infrastructure supporting the LW’s ability to work in person-centred ways with people with complex needs [23]. Within the context of caring professions, it is recognised that work-related stress can have a significant negative impact on retention [22].

Although there is growing evidence on the role of the LW and a general consensus on the need to theoretically understand how their role is shaped, research is still needed about the factors that influence the recruitment and retention of LWs [27, 28]. Some have suggested that increased attention to LW training needs is required [23]. Moreover, the evidence reporting on the impact of the LW role has focussed on the adult population. There is a dearth of research that has evaluated the impact of the LW on CYP’s ability to self-manage their mental health [29]. This is echoed in Hayes et al.’s rapid review which identified limited evidence relating to the impact of social prescribing more broadly on CYP [12].

Building on this context, Barnardo’s, a leading UK children’s charity, has supported CYP and their families by ensuring that their voices are central to care. The Barnardo’s Social Prescribing LINK service, which uses the Child-Directed, System-Focused, Strengths-Based, Outcome-Informed (CSSO) framework, prioritises empowerment through strengths-based approaches to promote positive growth and development. The CSSO model emphasises leveraging the strengths and resources of children, young people, and their families to achieve better outcomes. This approach is collaborative, involving the person supported by services and those providing support working together to determine outcomes based on the person’s strengths and assets and is underpinned by the UK Department of Health and Social Care statutory guidance [30]. As such, the CSSO model reflects the principles of personalised care. This social prescribing initiative, established in 2020 for CYP aged 5–19, collaborates with five PCNs to support emotional health and well-being. In partnership with Barnardo’s, we are evaluating the service’s impact on CYP, their families, and other key stakeholders, as well as its integration across multiple sectors. This study aimed to explore the experiences of LWs working with CYP, focusing on service delivery, job satisfaction, career development, and retention, addressing a critical gap in research on LW roles and their influence on CYP care. In doing so, we aim to contribute to knowledge about LW roles and their influence on CYP care. We believe this is one of the first studies to evaluate the experience of LWs working with CYP.

2. Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach and Research Paradigm

To frame our research, we used a qualitative approach influenced by a constructivist paradigm to explore the LW experiences and gain an understanding of the LINK service and how CYP were supported. Constructivist approaches can facilitate insights into the context in which services, such as LINK, are delivered and support the capture of unique experiences [31]. We used Braun and Clarke’s [32] validated framework to interpret the data and identify common themes. We used the themes to develop a conceptual framework.

2.2. Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

The research team consisted of five members with backgrounds in nursing (MH, EA), social work (JF), physiotherapy (PC), and integrated service provision (AK). The combined professional experiences enriched the reflexive approach through emphasising critical awareness which influenced the ‘learning partnership’ and enhanced transparency of the findings [33]. As part of the learning partnership, the research team met quarterly to review progress and learning. Reflexivity was facilitated through triangulating the viewpoints of the researchers with the data to ensure that the research findings were grounded within the data. This created a dynamic approach which informed all stages of the research including the agreement of the research questions, analytic approaches, and data collection tools used to evaluate the impact of the LW on CYP. All research team members were involved in the development of the research design; PC led data collection, and MH, JF, and PC undertook data analysis. The research team and LINK team met regularly to reflect on and discuss the findings, which also helped to identify and manage the research team assumptions and enabled a critical reflection on the implications of learning for future service delivery.

2.3. Sampling Strategy

We used a purposive sampling strategy, as this approach is known to enable the inclusion of participants who can facilitate an in-depth understanding of the phenomena, thereby helping to achieve the study’s aims. This enhances the rigour and trustworthiness of the research as results are more likely to be easily contextualised through member checking. Sampling within a constructivist paradigm is often iterative and data collection and analysis took place simultaneously as a result. This also meant that the research team continually reflected on their influence on the process [34]. The structure of staffing within the LINK service included a children’s services manager, two team managers and two senior LWs. We included all LWs and managers who had participated in the provision of the service for CYP and families. Invitations to participate were sent via secure email by a gatekeeper within the organisation, and interested staff were then sent an information sheet and consent form by a member of the research team before scheduling semistructured interviews. The consent forms enabled the recording and use of data extracts for publications and reports. There was a total of 17 LWs, of which three were managers, two were senior practitioners (with 2 years or more LW experience) and 12 were LWs. All the LWs had prior experience of working with CYP either as youth workers, youth support or in education. Geographically, the LWs covered five PCNs in the North West of England.

2.4. Ethical Issues

The study was approved by Barnardo’s Research Ethics Committee (Ref: BREC [35] 2022). Ethical issues were addressed by ensuring that participants were informed about the evaluation and only contacted if they gave prior consent. Participant information sheets were provided in advance, and the research team met with LWs to explain the project and respond to any questions. A comprehensive data management plan was developed and approved to ensure data security and adherence to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

2.5. Data Collection Methods

Qualitative, one-to-one semistructured interviews with LWs and managers were conducted between April 2023 and February 2024. Semistructured interviews are recognised for their ability to enable researchers to explore the phenomena in detail and gain rich insights. Interviews with LWs and managers enabled investigator autonomy to explore pertinent issues relevant to LW’s experiences [35]. All interviews were conducted remotely online using Microsoft Teams at a time convenient to participants. The interviews lasted between 20 and 55 min and were on average 30 min long. The research team utilised a semistructured interview schedule to explore concepts and responses in more depth through follow-up questions. Interview questions were open ended and encouraged the LW to describe their role, and reasons why a CYP may be referred to the service. We also asked the LWs to describe their views about the impact of the LINK service on CYP and families and the LINK service delivery model. All of the interviews were digitally recorded with permission from participants, transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

2.6. Data Analysis

The constructivist approach facilitated theoretical saturation of the data through the ongoing analysis and data collection process [34]. We used a structured approach based on Braun and Clarke’s [32] thematic analysis framework. This enabled the research team to systematically move from codes to the final themes. To identify initial codes, anonymised interview transcripts were imported into ATLAS.ti qualitative analysis software to facilitate the organisation and management of data. The team met regularly to discuss the development of codes, which were then assigned with labels that best described the data. During meetings, the team then further refined the codes by exploring patterns and connecting them into themes that represented the overarching concepts. Braun and Clarke’s [32] thematic analysis framework built on the codes and enabled the identification of common themes across the 17 interviews. The themes were cross-checked and further interrogated independently by the research team.

2.7. Trustworthiness of the Findings

To enhance trustworthiness, the research team met regularly to review and refine the analysis. This approach helped to ensure that data interpretation was consistent and dependable, allowing for a thorough discussion and reconciliation of different perspectives [36]. This further influenced the transparent and rigorous development of codes from raw data [36]. This method was used to help ‘sense check’ the initial analysis undertaken by ATLAS.ti as it can improve the rigor of the data analysis through enabling transparency about the open coding and how this was developed from the raw data [37]. The team met to discuss and agree the final themes. Final themes were shared with the LINK team for member checking to ensure data saturation and enhance the credibility of the analysis [37, 38]. The team then revisited the raw data and themes to expand or refine areas based on the discussions.

3. Findings

Our findings identified five core themes that highlight how a transformational leadership approach contributed to LW job satisfaction and retention. These key themes were: supportive leadership and a collaborative team environment, promotion of flexibility, autonomy and work–life balance, access to continuous professional development (CPD), opportunities for career progression, and the ability to achieve meaningful impact in their roles.

Transformational leadership is an approach initially conceptualised in 1978 and was one of the first leadership styles to recognise the importance of inspiring and motivating staff [39]. It is reported that transformational leadership centres on how leaders can motivate and inspire, fostering a positive organisational culture by creating supportive work environments [40]. This leadership approach enhances staff retention through inspirational motivation, individual consideration, and idealised influence [40]. As such, transformational leadership has gained considerable popularity and positive recognition in recent decades [41, 42], cultivating a culture where staff feel valued. Furthermore, a high-level meta-analysis suggested a relationship between transformational leadership and employee performance, implying that this leadership style can elevate employee morale and positively impact performance [43]. Hence, transformational leadership is a style often used as it can help drive improvements in efficiency as well as transferring knowledge to enable and enhance practices [44].

This leadership approach may have played a role in enabling the LWs to collaborate across a range of sectors, supporting wider integrated service delivery. The findings provide insight into how the LINK service contributed to the development of these roles and the ways in which the LWs were supported. This approach appeared to have a significant impact on the development of the LW progression as an individual and as an organisation as it allows for creativity and innovation, satisfaction, and commitment, which in turn supports retention and positive relationships with leaders [45]. Themes are discussed in detail below, accompanied by supporting quotes to illustrate each theme.

3.1. Supportive Leadership and Collaborative Team Environment

“The team, it’s so supportive. They will help you with anything, and they’ll make sure that you get to the point that you need to be…you are never left on your own” (LW17).

“We’re all encouraged to share our thoughts and feedback, which creates a culture of openness and collaboration” (LW14).

“There’s a real sense of teamwork here, and that’s thanks to the culture management has built” (LW15).

“The management is very approachable. If there’s any issues or challenges, we are never left alone to deal with them” (LW16).

“I suppose the caseloads can be challenging, and it affects you in some ways, but the team is always there to support you” (LW17).

Additionally, mutual support among peers fostered a keen sense of belonging and collective job satisfaction. This environment not only enhanced individual well-being but also contributed to the overall effectiveness and cohesion of the team.

3.2. Flexibility, Autonomy, and Work–Life Balance

“It’s a healthy work-life balance here…You can start early, finish early, and take time off when needed. It’s really flexible” (LW11).

“There’s flexibility in the working hours, and we can adjust our schedules based on the needs of our cases, which helps a lot” (LW15).

This flexibility and autonomy not only enhanced job satisfaction and retention but also enabled the LW to provide person-centred, convenient, and timely support based on the CYP and families’ priorities and needs.

3.3. Comprehensive Training and CPD

“There’s always training available to help us improve. I’ve done a lot of training since I started here, and it’s all been really helpful in building confidence” (LW11).

“We are always looking at further training and development opportunities. They really encourage us to keep learning and growing” (LW14).

“We’ve had a lot of mental health training, which is crucial because a lot of the young people we work with deal with anxiety and other mental health challenges” (LW15).

3.4. Job Satisfaction Through Meaningful Impact

“I just love helping the young people in their homes and at school. It’s just great. There is a huge mix, and a huge mix of ages as well” (LW11).

“The work we do is so varied depending on what the young person wants, and that’s what makes it special” (LW15).

Generally, the LW experienced heightened job satisfaction when they observed a tangible, positive impact of their work on the CYP they support.

3.5. Opportunities for Career Progression

“There are definitely opportunities for progression. You can take on more responsibility and potentially move into more senior roles over time” (LW11).

“I feel like there’s room to grow here. They encourage you to learn and develop your skills, and that opens up opportunities for moving up within the team” (LW15).

The Barnardo’s CYP SP LINK model enables LWs to advance and facilitated clear pathways for career development. This helped to enhance the LWs skills and knowledge and help reduce attrition and increase long-term engagement within the organisation.

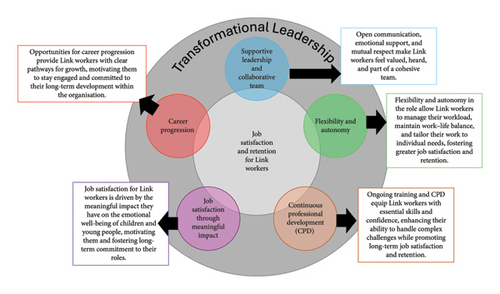

Significantly, our findings highlight several important and previously unreported factors that were identified by LWs which contributed to job satisfaction and retention. The leadership approach described by the LWs aligned with core principles related to a transformational leadership style. To illustrate this, we have integrated the factors within a unique conceptual model that illustrates the core components that influence LW job satisfaction and retention (see Figure 1). These included leadership and a collaborative team; flexibility and autonomy; CPD; job satisfaction; and career progression.

The conceptual model illustrates how a supportive and transformational leadership style influenced a creative, collaborative team environment which supported role flexibility through autonomy, ongoing training and CPD, and career developments.

4. Discussion

We aimed to explore the experiences of LWs working with CYP, focusing on service delivery, job satisfaction, career development, and retention, addressing a critical gap in research on LW roles and their influence on CYP care. To our knowledge, our evaluation is one of the first to report on how these experiences have been influenced by a transformational leadership style. The role of the LW was crucial to the success of integration across multiple sectors and illustrated the way in which person-centred, salutogenic approaches can support CYP and families. Our findings present a unique insight into the LINK service in terms of its delivery, organisation, and impact within wider integrated services. Collectively, the five core components enabled LWs to collaborate with CYP and families creating the conditions for meaningful impact. Each of the core components are integral to a sustainable service and are therefore interconnected. The symbiotic relationship between the components illustrates the comprehensive approach needed to create a sustainable service underpinned by experienced and satisfied practitioners. Next, we explore each of the components through explicating the inter-relationship to understand how this model could be transferred to similar services to support sustainable growth of staff and service provision within the integrated care sector.

4.1. Supportive Leadership and Collaborative Team Development

Supportive approaches are often associated with a transformational leadership style which has been described as an approach whereby the “dynamics of transformational leadership involve strong personal identification with the leader, joining in a shared vision of the future, or going beyond the self-interest exchange of rewards for compliance” [46] (p. 695). Historically, transformational leadership has influenced increased performance levels [47, 48] and can ultimately influence job satisfaction as it allows for open communication, emotional support, and mutual respect. These are core attributes described by the LWs who shared that this made them feel valued, heard, and part of a cohesive team. Invariably, the inter-disciplinary nature of the role meant that LWs needed to work across a range of sectors such as schools, Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), and PCNs to ensure that they were meeting the child and family’s needs. Transformational leadership styles can empower employees by enabling flexible working and providing autonomy in their roles [49]. This approach allows employees to take control of their career development [50] and enhance role satisfaction which may have positively influenced retention.

4.2. Flexibility and Autonomy

The incidence of children with co-morbid and complex needs is increasing, placing additional demands on parents and necessitating a broader integrated and interprofessional approach [51]. Strong transformational leadership approaches can facilitate agility in the workplace, and for LWs, enhance their ability to build on person-centred approaches and focus on what matters most to CYP and families. This approach fostered a deeper understanding of each individual’s personal context. Invariably, the ability to work flexibly enables autonomous practice that respects the values and preferences of CYP and families. It is understood that autonomy of practice and decision making can lead to greater cooperation in care and improved health and well-being outcomes [52]. The degree to which LWs were able to practice flexibly may have influenced their practice, health outcomes for CYP, and job satisfaction. Autonomy fosters a culture of trust and is linked to higher levels of job satisfaction [52]. Similarly, the level of autonomy underpinned by trust can produce lower levels of stress and burnout which is described as “long-term, unresolved, work-related stress, with feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment as central features” [53].

The increasing incidence of complexity amongst CYP and families that LWs support also carries an increased degree of risk of burnout and highlights the need to support staff working in this area [54]. Supporting CYP and families with complex needs can be challenging and can create additional stress on LWs and equivalent roles. The flexibility and autonomy engendered through the transformational leadership approach can enable LWs to manage their workload and work–life balance which can also influence greater job satisfaction.

4.3. CPD and Opportunities for Career Progression

Career progression of employees is crucial to the sustainability of the social prescribing service and integral to the provision of high-quality and effective care. The ability to develop a career pathway is built on transformational leadership, understanding of the individual LW training needs and through offering structured CPD. Transformational leadership approaches that support autonomy can enable individuals to identify their own training needs and future career pathways [55]. Career progression was an important factor highlighted by LWs and is also echoed in the literature [47] as essential to ensuring employee satisfaction, growth of a service, and ultimately the retention of staff. Social prescribing LWs originate from diverse backgrounds and may have existing professional qualifications, such as an occupational therapist, or may have experiences of the community setting through community outreach work or project management. Over the past 5 years, the role of the LW has grown, shaping and influencing career developments within the profession.

Support for a career pathway is reported in the NHS England Social Prescribing LW (SPLW) Competency Framework [56] which sets out the standards expected from SPLWs. Hence, SPLWs are encouraged to develop a portfolio of evidence and clinical supervision that are transferable to other roles. This includes personalised care, coaching, data management and reporting, along with other skills that support the development of LWs careers. It is evident from Tierney et al. [57] that getting LWs into the workforce is crucial, but how this is operationalised is important in shaping the role, especially acceptance from other professionals. Forging an identity for LWs is key, building a facilitative structure around them to ensure they can deliver a valued meaningful contribution to the people they are caring for [57]. The inclusion of career pathways is thought to be crucial to the growth and career development of an LW service more broadly, as it has been reported that as many as 29% of LWs have considered leaving [58]. From these, 77% were based in GP practices [58]. Similarly, other research highlighted that half of LWs surveyed (n = 342) had considered leaving their role in the past 6 months and reported that many felt unsupported and had limited time for training [24]. LWs often feel unprepared for the complexity of the role and can struggle with isolation [59] which can influence increased attrition rates. Moreover, it is recognised that training can support career progression and ultimately influence an employee’s desire to stay in a post [60].

Ongoing career development is influenced by the LW’s ability to undertake CPD which is crucial to the ability of professionals to provide a safe and effective service [61]. Significant resources are often spent on CPD to empower employees to deliver high-quality services and care. Equally, employees can benefit from a range of impacts associated with attending CPD including social learning, engagement with communities of practice and skill acquisition [61]. In other professions, CPD is reported to improve overall job satisfaction and subsequent retention [62]. This is particularly significant within the context of the CYP sector as rates of poor mental health in CYP continue to rise [5], and services become increasingly limited to provide support. Therefore, support and subsequent retention of LWs is essential to the sustainability of the social prescribing service and LW role.

4.4. Job Satisfaction Through Meaningful Impact

Job and role satisfaction are reported to influence low attrition rates [63] and can foster loyalty and commitment to remain in an organisation [64, 65]. Equally, in our findings, effective team working across the service and good relationships with senior managers also influenced strong collegiality and support. The supportive and compassionate culture described by the LWs appear to have been influenced by the transformational leadership approach which actively seeks to encourage, inspire, and motivate employees to perform in ways that create meaningful change. This highlights why it is used widely within healthcare [66] as it enables a caring organisation to support staff to thrive [67]. It is acknowledged that transformational leadership can enhance the relationship between workers leading to increased commitment to the organisation [68]. Invariably, this approach can reduce the risk of burnout and can improve workforce resilience and productivity [69]. Ultimately, our findings suggest that a transformative leadership approach fostered a positive organisational culture, which in turn influenced overall job satisfaction [57].

4.5. Implications for Future Practice

Previous research has reported that the integration of LWs into the workplace through centralised power may leave LWs feeling marginalised [57]. It is suggested that LWs need to establish a clear identity and be viewed as integral members of the team which can improve retention [59]. Our findings indicate that using a transformational leadership approach can improve retention and influence job satisfaction. LWs need to be able to demonstrate their impact with CYP and be supported to do so effectively. This has significance for the leadership and development of LW services within CYP contexts.

4.6. Limitations

Our sample frame was purposive and limited to Barnardo’s LWs, which may influence transferability of findings to other LW contexts. Whilst we achieved data saturation, our findings need to be considered in context of the LINK model and the CSSO framework that was used to support the CYP.

5. Conclusion

Our findings offer a unique perspective on the work of CYP LWs, showing how a compassionate organisation, influenced by transformational leadership, fosters growth and job satisfaction among LWs. The leadership approaches used enabled LWs to develop their skills and work towards a defined career pathway. Ultimately, LWs were empowered to work autonomously across a range of sectors providing a consistent person-centred service to CYP and their families, including some of the most vulnerable groups in society.

Conflicts of Interest

M.H. resides on the National Social Prescribing Network Steering Group and is a member of the International Social Prescribing Alliance. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by the Barnardo’s Foundation as part of a wider Learning Partnership between the research team and the charity Barnardo’s, RJB/DRJ/76918/120030/UKM/65134336.2.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are only available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.