Creating a Conducive Zone for Innovation in Children’s Social Care

Abstract

Innovation activity in child and family services has accelerated over the past 2 decades, particularly in England, where substantial government investment in pilots, diffusion activities and evaluations has created an emerging body of literature on effective approaches and characteristics of efficient practice systems. However, the literature on the interplay of enabling or impeding factors and processes at a local and national level tends towards the descriptive, while theorisation of the underlying dynamics remains limited. This paper presents the findings of a framework analysis produced through integrating thematic insights from a narrative review of academic and grey literature with those drawn from interviews with 21 expert informants engaged in social care innovation within the UK within policy, leadership or researcher roles. Analysis enabled five clusters of ‘conditional parameters’ to emerge, covering: mobilisers; system capabilities; design and implementation features; organisational culture, climate and processes; and the macro context. Three or four conditional parameters are identified per category, each outlining factors and processes that could either facilitate an innovation or create barriers that needed to be overcome. To achieve an environment most conducive to innovation, attention needs to be paid to the interplay of these conditions, recognising that their operation and influence might be occurring out of awareness and scrutiny. Innovation is found to be best facilitated by a stable, well-supported workforce that feels energised and confident to create and implement change. This requires developing a supportive, collaborative, relational culture and climate of mutual trust, where reflexive supervisory and evaluatory mechanisms follow the human-centred grain of professional practice and where staff feel safe to experiment and make mistakes. This can enable a conducive zone for innovation to open up, even where policy drivers and the availability of resources are less than optimum.

1. Introduction

Innovation becomes an imperative for the public and welfare sector when social problems are getting worse, when current approaches are not working or when institutions and systems reflect past rather than present problem formulations [1]. The confidence of the social care field has increasingly been placed in social innovation’s potential for troubling prior practice and policy paradigms, encouraging experimentation and—often radically—transforming services and interventions [2, 3]. This confidence has been reflected in substantial investment in innovation by public services, philanthropy, the charitable sector and social enterprises [4–6]. Such investment has enabled evidence on the effectiveness of new interventions to start to emerge; yet, unlike in other areas of the public sector, such as the UK National Health Service [7], rigorous investigation of the phenomenon of innovation within social care is relatively underdeveloped [8, 9].

This gap in the knowledge base lay behind the funding of studies such as ours, by the Economic and Social Research Council in the United Kingdom, to investigate the processes of innovation in children’s social care1 (https://www.theinnovateproject.co.uk). To map local and global understandings and practices of innovation within this sector, we reviewed the international literature and conducted interviews with 21 expert informants across the United Kingdom. Together these methods inquired into (1) how innovation is defined and understood in children’s social care; (2) what might be expected at key stages of an innovation journey; (3) the factors that support the mobilisation, progress and effectiveness of innovation in this sector and (4) strategies which might pre-empt or address challenges.

The analysis relating to the first and second questions has already been published in our papers on ethical considerations in social care innovation [10] and common stages of the social care innovation journey [11]. The current paper concerns the latter two: how innovation might be enabled, and barriers overcome, in children’s social care. We addressed these questions through a framework analysis that integrated the data from the literature review and interviews, using a hybrid deductive–inductive thematic analysis approach [12]. This analysis enabled a complex web of underlying conditional parameters to be revealed which, taken together, might either form a ‘conducive context’ within which innovation may be facilitated, or its reverse.

The findings have particular relevance for the understanding of innovation processes in UK children’s social care, given the rich contextual detail and critical perspectives offered by the informant interviews. As a result, we begin the paper with a brief overview of the UK context. The findings offer insights, too, for innovation in other countries which configure family welfare and social care around similar principles, given the international scope of the literature review. However, the transferability of findings to other countries does need to be carefully considered with reference to comparability of context, particularly given our finding (detailed below) that macrolevel policies and cultures exert considerable influence over local practices and the availability of resources.

2. The UK Context for Social Care Innovation

The challenges facing children’s social care are well documented through commissions, reviews and inspections in the four countries of the United Kingdom [13–19]. Entrenched and emergent social problems are increasing service demand in a cash-strapped public sector [20–22]. Significant budget cuts across social care and related sectors are exacerbating significant challenges with staff recruitment and retention [23, 24]. A general lack of robust evidence and data about how to set appropriate and realistic outcomes and judge whether they have been met is limiting sector learning [2, 25, 26].

These challenges create a noxious blend of worsening and emerging issues, a system straining under the pressure and structures that are increasingly ill-designed to cope with the challenges with which they are presented. Increasingly viewed as a ‘silver bullet’ in the United Kingdom to address the perfect storm of increased demand and reduced resources, innovation has attracted significant funding from government, philanthropy and the charitable sector [27–29]. This is producing an increasing body of knowledge about the practice models and systems that are effective in supporting children, young people and families, and about some of the local and national factors associated with innovation succeeding in its aims [30, 31]. Yet, evaluations and implementation studies of individual projects remain ‘notoriously poor’ at rigorously analysing the factors and processes which facilitated or impeded their innovation process in ways that can be synthesised and modelled for sector planning and resourcing [8].

The variations in how concepts of ‘innovation’ and ‘improvement’ are understood and used by policymakers and practice leaders in social care further impede such synthesis. While ‘improvement’ approaches are predicated on introducing changes incrementally and cyclically so as not to overload or disrupt any part of the system and only moving forward when stability has been reached [32], innovation, in contrast, requires a higher degree of creativity and risk-taking, as outcomes are uncertain, and so is more demanding of those leading or implementing the process. It entails a ‘radically different way of thinking and acting’ from existing or conventional services and approaches; hence it is expected to transform structures, methods or fundamental assumptions about people and social processes [33]. At heart, ‘innovation’ simply refers to a framework or model that is either entirely new or involving the adaptation of an existing approach to a new setting or discipline. However, as we have argued previously [10], innovation within children’s social care should be located within the social innovation canon, which implies an underpinning aim of advancing social benefit. Given this, innovation may be more resource-intensive than improvement: an innovation design might need to be revised several times during piloting and, in statutory services, there may need to be additional funding to meet existing obligations while a new approach is in development [1].

As a consequence, the barriers experienced by individuals and organisations, and the ways of overcoming these, are often different for innovation, compared with continuous improvement measures or the introduction of more conventionally conceptualised interventions. Failing to distinguish between them hinders the goal of a comprehensive understanding of the variety of factors and mechanisms which mobilise, facilitate or impede effective innovation within children’s social care and how these operate and interrelate within their systemic and organisational contexts [30, 34].

3. The Research Approach

3.1. The Literature Review Method

Initial exploratory database keyword searches scoping the nature and scale of the literature revealed that a systematic review was neither appropriate nor achievable. First, terms such as ‘innovation’, ‘innovate’ or ‘innovative’ were used with varying degrees of consistency to describe or denote newness or change processes, but often without a specific focus on a named innovation. Second, there was relatively little to be found on what makes children’s social care a distinctive space within which to innovate, compared with industry, business or other areas of the public sector [8]. Third, the paucity of large or robust empirical quantitative or mixed methods studies designed to identify the factors which facilitated or impeded innovation in children’s social care meant relevant information had to be sifted out from disparate kinds of study, where the focus was more likely to be an innovation’s feasibility or effectiveness. As a result, a narrative synthesis approach was initially chosen [35], leading to the identification of broad themes that were further refined and mapped within a framework analysis.

Six databases (ASSIA, Scopus, SCIE, Web of Science, ProQuest Business Collection and PsychInfo) were searched electronically using search strings. We also hand-searched all issues published since 2005 of seven journals regularly reporting findings from innovation projects or theorising innovation processes (The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, International Social Work, British Journal of Social Work, Journal of Social Work, Health and Social Care in the Community, Child and Youth Services Review, Children & Society). Articles that were particularly relevant to the review were reference and citation chained and a call for relevant literature was issued through the project team’s (largely UK-based) sector contacts.

To be eligible for inclusion, literature had to be written in English, published after 2005, and concerning innovations sited within child and family services, as either a sole setting or as a lead agency, and geographically located in the United Kingdom or another industrialised nation with a comparable approach to children’s social care.

A total of 3819 items were returned through these means, saved to a Zotero (referencing) database, and screened by the third and fourth authors for relevance. Duplicates and items other than academic articles were removed, leaving 1802 entries. Each title was screened and those that obviously did not meet our inclusion criteria were removed (the majority were articles on innovations in health interventions and health-related technology). The abstracts of the remaining 304 items were screened for relevance. One hundred forty-four of these were read fully, but 65 excluded on further scrutiny. This left a core sample of 79 peer-reviewed journal articles, the majority of which concerned quantitative (11%), qualitative (49%) or mixed-methods (27%) project evaluations or reports of implementation studies conducted in either the United Kingdom or North America. None focussed specifically on the factors that facilitated the process of innovation or how identified challenges might be overcome; rather, we had to search through each item to find what were often just snippets of insight into these questions. Hence, this should be seen not as the kind of bounded core sample that would be seen in an evidence review, but rather a web of literature that could be interrogated and thematised to shed light on our research questions.

A grey literature search was conducted to identify background material within which UK social care innovation could be contextualised. Two hundred seventy-five relevant grey literature items documents were identified through web-searching, citation-chaining and a call for literature through social media and the project team’s advisory network. Approximately half of these comprised reports, commentaries, think pieces, books, frameworks and toolkits by private or third sector organisations or individuals, offering learning from implementation and diffusion activities in the public and voluntary sector. The remaining items were rooted either entirely within UK children’s social care contexts (176 documents) or at its interface with youth justice, child and adolescent mental health, community safety and interagency safeguarding systems (48 documents) and comprised: evaluation reports of individual projects; policy, guidance or reports by government, parliamentary and nongovernmental public bodies; learning reports from large-scale innovation programmes; and national reviews of care and safeguarding.

3.2. The Interviewing Approach

Simultaneous to the literature search, ‘expert informants’ were interviewed by the third author to situate and consider the implications of the review findings for the UK context. Purposive sampling techniques were used to identify a ‘long-list’ comprising senior sector leaders, policymakers, operational leaders of large or influential innovation projects, representatives of third sector organisations with a specific interest in innovation in the children’s social care sector and academics who had been engaged in commissioning, shaping, evaluating or conceptualising social care innovation within the United Kingdom in recent years. These individuals were identified through a request to our advisory network for relevant nominations. Fifty-four people were sent an information sheet and consent form, inviting them to participate, and 21 agreed to do so.

Semi-structured interviews took place on the telephone or via Microsoft Teams video conferencing software. Interviews lasted 30–90 min and were audio recorded and transcribed. A broad topic guide was followed to ensure priority areas of inquiry were covered, but the interview was more of a dialogic conversation [36]. The exploration developed interview by interview as we sought clarification, confirmation or contradiction on what we had learnt in the earlier interviews and from the literature.

Quotations from interviews have been selected for this paper as emblematic of key themes discussed and to capture the highly contextualised nature of interviewees’ narratives. Each interviewee has been assigned a code from P1 to P21 so the balance and spread of their contributions from across the sample is transparent.

3.3. Ethical Approval

Standard ethical processes were followed, for example regarding informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality and secure data storage. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Sussex Research Ethics Committee.

3.4. Framework Analysis of the Literature Review and Interviews

‘Framework analysis’ was selected as it offers a pragmatic, flexible and rigorous way of managing, mapping and interpreting a large and disparate qualitative data set to answer focussed questions within applied policy and practice fields [37]. As the approach employs an organised structure of inductively and deductively derived coding, we were able to work concurrently and iteratively between the literature review and informant interview analysis, so that each could shed light on the other and contrasting perspectives or gaps could be identified. The approach comprises six stages: familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping; and interpretation [38].

The first stage began with a dual stranded immersion in, and dialogue between, the literature and interview transcripts to identify preliminary codes. We were expansive and generous in our inclusivity of codes at this stage. Sections of particularly relevant text in the academic sample of literature were copied into an Excel spreadsheet containing bibliographic details of each item, with possible codes flagged for each. The first reading of each interview transcript (in Microsoft Word) entailed the highlighting of words and phrases which seemed significant with reference to our research questions, and the use of the ‘Comments’ function in Word to provide short memos or commentaries. At the second reading of the transcripts, those which might constitute possible codes were tabulated on a separate spreadsheet.

We started Stage 2 by comparing the two sets of preliminary codes to identify those which were appearing with some regularity, or a degree of intensity, in one or other data set; those which shone through both were highlighted. Clustering the codes produced an initial thematic framework of factors and processes potentially influencing the extent to which an innovation could mobilise, gain traction and flourish; these included mechanisms (e.g., coproduction), attitudes (e.g., fear of risk) and contextual conditions (intraorganisational, local and national) (see Table 1).

| 1. | Motivation and purpose |

| 2. | Values, vision and commitment |

| 3. | Understanding of innovation processes |

| 4. | Organisational culture and ways of working |

| 5. | System features |

| 6. | Innovation design |

| 7. | Collaboration, partnerships and competition between organisations |

| 8. | Coproduction and participatory approaches with children and families |

| 9. | Risk, failure and adverse consequences (actual and perceived) |

| 10. | Data, measurement, evidence and learning |

| 11. | Money (markets, funding and commissioning) |

| 12. | Leadership, governance and power |

| 13. | Inspection, regulation and political environment |

In Stage 3 (indexing), we coded all of the interview transcripts and literature snippets to this initial framework using NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Additional subcategories descended from each of the thirteen ‘tree nodes’, based on the longer list of preliminary codes as well as further inductive coding stimulated by this further layer of data familiarisation. As we began Stage 4 (charting), it became clear that the initial framework was too disparate and lacked coherence. There were too many subcategories and horizontal connections across subcategories, which suggested that the framework should be condensed and refined—a common need at this stage of framework analysis [38]. A reordered framework was constructed of five clusters, each containing three or four ‘conditional parameters’ potentially exerting influence on the innovation process. All data were subsequently recoded on Nvivo to this framework, and then ‘charted’ to summarise the data for each category. The final stages, mapping and interpretation, created coherent insights into how each conditional parameter might spawn barriers or facilitators, depending on local and macro factors (see Table 2).

| Clusters of conditions | Conditional parameters for innovation | Key facilitators | Key barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilisers | Vision and values | A clear vision underpinned by shared principles | Misaligned priorities or perspectives |

| Motivations | Innovation likely to achieve the transformation necessary to improve user outcomes | Crisis responses or financial issues drive the innovation vision | |

| The case for change | A realistic proposition that will secure buy-in | Inadequate theory of change | |

| Design and implementation features | The degree of ‘fit’ | The right innovation, in the right place, at the right time | The innovation doesn’t work, politically or practically, in this context |

| The innovation design | Optimal and achievable design, tailored to this context | Lack of clarity about what innovation involves and requires | |

| Coproduction | Consultation and coproduction with families prioritised and resourced | The resource-intensiveness of lived experience and voice is not planned in | |

| The implementation process | Well-planned, reflexive, data-informed implementation | Systems cannot provide the data necessary for planning and ongoing evaluation | |

| Operational capability | Workforce capacity | A sufficient, stable workforce | Staff too busy to innovate and learning dissipates when they leave |

| Workforce knowledge and skills | Staff have the required skill-set | Staff unable to translate the model into practice | |

| Finance | Sufficient financial resources for every innovation stage | No ring-fenced money to enable the innovation to incubate and sustain | |

| Leadership | Strategic, skilled, stable, supportive leadership | Leadership turnover dissipates ownership of the vision | |

| Organisational culture, climate and processes | Collaboration and participation | Collaborative and participatory practices within and across organisations | Clashing values and perspectives, top-down processes |

| Attitudes | Flexibility and openness to risk, uncertainty and complexity | Fatigue, resistance, cynicism, silo-thinking and fear of adverse consequences | |

| Trust, emotions and relationships | Trust experienced vertically and horizontally | A blame culture, emotions are not contained | |

| Learning and evaluation | A learning culture | Feedback loops not built in, ‘failure not an option’ | |

| The macro context | Professional and regulatory conditions | Macro systems are permissive and flexible | Overly bureaucratised systems |

| Political and policy agendas | A well-resourced and politically supported social care sector | Resource availability and policy direction driven by short-termism and marketisation | |

| Public perceptions | Positive public and media perceptions of social care | Negative perceptions of social work and public sector create risk aversion | |

On the whole, only findings for which there was meaningful resonance across both the literature (grey and academic) and interview transcripts were included in the framework. The exception is for the ‘macro context’ cluster (see Table 2), where the interviews provided most insights—indeed, one of the commonly expressed reflections of the interviewees was that there was insufficient critical published material regarding the complex factors and processes which often operated outside of public scrutiny, particularly regarding political influence and the sensitivity of innovations that had failed, which tended to disappear almost without trace.

4. Findings: The Conditional Parameters for Innovation

Five clusters of conditions were identified that exerted a strong influence over the innovation process. Table 2 sets out the conditional parameters for innovation within each cluster and itemises the key facilitators and challenges related to each. The following narrative sections discuss and counterpose these enablers and barriers within each cluster.

4.1. Innovation Mobilisers

A clear and practical vision by the key players is a crucial starting point. Creating a ‘shared vision, you know that sense of actually we’ve got a joint shared problem or thing we want to solve or change’ (P2) enables the direction of travel to be established and ensures a more coherent plan of action [39, 40]. The aspired vision needs to align with the values and theoretical perspectives of the staff both within organisations and across partnerships to build a common understanding of how an innovation is envisaged to address a social or family problem, as dissonances can pose a significant barrier [41–46].

Money’s at the heart of this all the way through… people want to put their mark on things. People like their ideas to be bought, you know… the idea from design innovation to find something people didn’t know they want and then make them believe they want it. (P8)

This sort of excitable notion that everything needs shaking up and starting again, I believe, has been quite destructive … People latch on to (innovation) as the only way of producing cultural or social or economic change, and it isn’t the only way. (P3)

A likely reason for this, noted by Brown [8], is that, while barriers to innovation are well rehearsed, the literature rarely provides narrative analyses of innovations that had struggled or foundered so the arc of innovation journeys are poorly understood. Several interviewees queried how reports of innovations that failed to meet their goals seemed to have been ‘buried’. In contrast, stories were provided during interviews where, we suggest, formal public analysis of an innovation journey could have provided useful learning.

A strong case of ethical and practical worth is needed if buy-in from relevant stakeholders is to be secured. Without strategic or top-level leadership commitment and active support from the primary agency and interagency partners, a new system or intervention is more vulnerable to changes in personnel or strategic direction, particularly where the service comes under pressure from staff turnover, financial constraints or critical inspection reports [40, 48–51]. Senior buy-in was found most likely where a theory of change or logic model could indicate how the approach taken would contribute to the desired goals and was supported by robust data indicating likely outcomes and return on investment [39, 49, 52].

Actually the biggest thing you have to do is get that enthusiasm and that emotional buy-in to why you’re trying to make that change… if you don’t get people emotionally attuned and bought into what you’re trying to do and why you’re trying to do it, and a belief that this will make a difference, then it doesn’t work. (P13)

Proposals were deemed particularly persuasive if aspired outcomes were theorised to be achievable without adding to the volume of work (important to practitioners) or needing extra financing beyond the initial start-up costs (important to leaders) [41, 57].

4.2. Design and Implementation Features

It is easier for an innovation to gain traction where there is a good degree of fit with current service principles and wider systems [51, 58]: ‘It has to be compatible with the rest of your systems and structures… you’ve got to follow these regulations and procedures’ (P5). Fidelity to the underpinning model is considered central to evidence-informed practice as, where key components have changed, it will be unclear which mechanisms will have contributed to success (or not) [49, 59]. But context matters, and it cannot be assumed a previously tested innovation will follow the same journey or produce the same outcomes if spread or scaled to another area. Leaders need to understand how to tailor an innovation model to a local context and to align with statutory requirements [58, 60, 61]. This matters particularly with international transfer, where there are likely to be strong differences in culture, social conditions and legislative and policy frameworks [62, 63]. Approaches which offer a degree of flexibility within fidelity to achieve fit, particularly with respect to practitioner or service user perspective, were considered to be particularly amenable to scaling and spreading [49, 51, 58, 62, 64–68].

The social workers are like, ‘we know it’s really important to focus on the family’s strengths… we would really love to have the time to develop relationships with families…but in order to do that, the systemic conditions need to be right, so we need to have the time, and we need to have the supervisory support’. (P11)

You’ve got to educate senior managers about …what the potential barriers are in advance, how you overcome them… Will there be enough money to see it through, will they give you long enough to trial it properly? (P5)

Hearing that child and family voice re-centres us back onto why we’re doing what we’re doing, so we’re not getting lost in the process and the caseloads… this person in front of me needs this kind of help… it just helps people step away from the quite kind of project management-y nature of implementing and innovation. (P7)

Bringing together systems leaders, policy makers with children, and actually having that direct dialogue and involving children in co-design, and helping those policymakers in particular understand why the current frameworks and systems don’t work, and hearing that directly from children, seems to be much more powerful than reading it from us… it engages people on that hearts and minds level. (P21)

Interviewees professed substantial scepticism about the extent of consultation with families and whether ‘asking for views’ actually translates into acting on what families have said. There were limited accounts of formal coproduction activities, particularly for the most marginalised families, and a tendency towards traditional rather than creative and participatory approaches, such as inclusion of parents in planning meetings or on steering groups with preset professional agendas and communication processes. Overall, there is a lack of evidence about the effectiveness of specific coproduction methods, particularly as regards children and young people [70, 72, 73].

I can say to senior managers in local authorities, ‘in order to do this properly you will have to do it like this’, and they say, ‘well, we haven’t got time to do it like that, we don’t want to do it like that, you know we’re going to do it like this’. And I say, ‘well, that’s not going to work’. (P5)

Dedicated implementation staff are needed to monitor and track progress, tailor practices to balance fidelity and ‘fit’, and address obstacles [43, 48, 49, 52, 76]: ‘just driving it forward, making sure that there are clear timelines, clear meetings, people being held to account, the right data’ (P2). These dedicated staff need to have additional capacity to the usual service or organisations will be ‘constantly trying to get people to do it on the back of their day jobs’, with the result that change doesn’t happen efficiently or at pace (P2).

Reflection, learning and evaluation need to be built into every stage of innovation design and implementation. If data capture and learning processes and repositories are not in place, then learning cannot be utilised and shared more widely. It may be lost as the workforce turns over or new policy developments come on stream, and it is less likely that insights are systematically transferred from one site to the next where an innovation is spread and/or scaled [8, 59]. It is not just professionals who need to see evidence unfolding of the benefits of the new approach as it progresses, but also children, young people and families [58, 64, 76] so the evidence needs to be engaging: ‘It’s about having that narrative, it’s about having case studies, it’s about developing tools that can help you to evidence things’. (P13)

4.3. System Capabilities

Where people are so often either fire-fighting, they just don’t have time for reflection and that sort of, you know doing that helicopter thing of coming out of the current context and seeing it a little differently and reflecting on it and talking to others. (P2)

There are only so many new ideas, roles and tasks that systems and the ‘incredibly overworked’ (P15) staff within them can absorb if they are to see an innovation through implementation and embedding: ‘You come swanning in saying, ‘I’ve got a great thing for you to do now’ and they just think, “hell, no, I haven’t got any space in my head”’ (P14).

A UK recruitment and retention crisis, whereby staff move around in hope of a better working environment, become ill or even leave the sector completely, have left both staff and leaders in the United Kingdom in ‘survival mode’ (P21), lacking time for follow-through on implementation or the robustness to take risks [44, 45, 48, 51, 64, 81, 82]. High staff turnover means that learning and ‘organisational memory’ (P13) ebbs away and resources are eaten up by needing to re-train new staff in the innovation approach, establish new relationships and continually work on culture-building [83, 84]. These barriers to embedding have relevance far beyond the United Kingdom as child and family services are rarely well resourced. So, as well asking themselves in the first place, ‘do we have the capacity to innovate’, organisations need to focus on ‘getting the basics right’, such as manageable workloads and supportive supervision, which build ‘organisational stability’ (P21).

Implementation is facilitated where the workforce has the necessary knowledge and skills for the innovation [48, 53]. Although not all innovations are manualised, those that include tools, implementation resources and training content are more readily scaled [58, 63, 83]. Training needs are multifactorial [51, 64, 65]. Interactive training methods offering hands-on learning and skills practice were noted as being much more effective than didactic delivery at enabling workers to make the leap from theory to hands-on practice [43], particularly where observation, monitoring and feedback were included [64]. To prevent workers reverting back to old approaches or implementing innovation in a superficial or tick box way, learning from training has to be reinforced over time to prevent ‘drop-off’ (P14) by mechanisms such as shadowing [44]; coaching [51, 53]; processes to assess staff performance and fidelity to the model [85]; supervision attuned to and reinforcing the new approach [43, 59, 73]; and refresher training [55, 77, 86].

Innovation funding quite often is for one year, for two years, and there’s a danger that, you know, you set up this great innovation project and then when the funding goes, you simply can’t mainstream it because the money’s not there. It’s not because the will’s not there, it’s because you haven’t got the money there across the whole system. (P2)

But inadequacy, insecurity or inconsistency of funding will pose significant barriers through the innovation journey [58, 64, 73, 83]. The need for ‘pump-priming’ of start-up design costs, to generate proof of concept and produce early data on benefits or [85] is commonly acknowledged, but the necessity for sufficient resources to cover the additional costs of embedding a new approach, scaling it up across a service and ensuring it can sustain over time [50, 59, 87] is less well recognised. Needing continually to chase revenue streams for these latter stages saps energy and can cause innovations to stagnate or founder [82].

Where evidence of effectiveness is slow to emerge, funders and leaders may be reluctant to sanction an innovation continuing, particularly in the face of constrained resources. While the need to demonstrate outcomes and value for money is important [77], the timeline for spending ringfenced funds, and what is deemed realistic for delivering the expected impact, could be misaligned with the realities, given how long it takes for real change to occur [71]. This is particularly true of radical innovations requiring full-system restructuring, which might take 10–15 years to fully embed [3]. As a result, adopting manualised or ‘tried and tested’ (P15) programmes may be particularly attractive: ‘It’s totally understandable that they see something that looks, that looks doable and is like packaged up and they’ve got a blueprint and they know how much it cost a year to run and they just want to do it’ (P16). This, however, risks edging out disruptive or grassroots innovation.

Leadership matters at all stages of the innovation process and is as important in restarting stalled innovation as it is for initial mobilisation [64, 85]. Leaders need to be adept at spotting opportunities for things to be done differently, and relevant funding opportunities [61]. They then need the openness, flexibility, skills and confidence to make the necessary changes to structures or ways of working [65, 76]. Dynamic, visionary, inspiring senior leaders are able to energise innovation in their service by articulating and communicating a clear innovation vision, modelling freedom, cultivating trusting relationships among the workforce which spawn collaboration and codesign, and enabling people to take risks in their practice [51]: ‘they’re a kind of shiny front of house person who really galvanises people around them and kind of pushes stuff through, and people have huge amounts of trust and respect for’ (P16). Innovation-attuned leaders cultivate and embed a culture where workers at all levels are trusted, are encouraged to expand their capabilities and know that innovation is expected, supported and rewarded [82]. They recognise that mistakes happen and create a nurturing and safe environment with the necessary policies and processes to encourage workers to share, reflect, learn from things that have gone wrong and cascade learning back into the service or organisation [78]. Stability of leadership with continuity of messaging and resourcing is important [39], but the ‘churn’ associated with practitioners was also found in the senior leadership of UK children’s social care [41, 81]: ‘they essentially ping pong around the system and stay in jobs for maybe you know 18 months to three years’ (P8). Staff commitment to new approaches is undermined where they could not be confident leaders would follow-through and be accountable.

4.4. Organisational Culture, Climate and Processes

Collaborative, participatory and cooperative organisational cultures that value open communication and are honest about the limitations of the current service or ways of doing things enable people with diverse opinions to engage in debate and compromise [45, 57, 68, 82]. This fosters a sense of trust, opportunity and energy in the workforce towards innovation by staff who believe that change is achievable and beneficial and hence are more willing to commit the additional effort [46, 50]. Trust will need to be nurtured through relational and respectful working at every level, modelled by leaders: ‘not just paying lip service but actually listening to the sort of the people who are going to be implementing these changes (P10). Positive, empowering, inclusive cultures can enable the generation of ‘really genuinely new and interesting ideas’ (P16), ‘brilliant, creative solutions… pure genius…think(ing) outside the box’ (P2). A common view of the gaps or problems in the system and potential solutions to address it may then be constructed ‘in a collaborative way with the people on the ground who know what they’re doing, know how it’s going to play out’ (P11) [46, 48, 49]. Engaging staff democratically from the start builds commitment, grounds an innovation in practice realities and facilitates tailoring to local contexts [60, 67].

However, concerns about organisational and individual resistance to change were reported widely. Innovations that require a shift in professional identity, contest practitioner autonomy or require them to adopt a different role can be personally challenging for staff [56, 61, 83, 88]. While personality factors might play a role in such attitudes to change [89], the impact of situational stressors might unfairly be characterised as resistance [58]. Frontline staff in the United Kingdom were described ‘time-poor’ and experiencing ‘innovation fatigue’ (P3), ‘overwhelmed’ by constant changes to policy and practice ‘when they’re just trying to get on and do a day job’ (P4). The intensive ‘fire-fighting’ nature and working environment of children’s social care in the United Kingdom had made it hard for staff to ‘rise above the fray’ and see a ‘bigger picture’ (P2), but the crisis-orientated nature of child welfare work in countries beyond the United Kingdom similarly leaves little energy or time to implement innovations when they are being also asked to maintain existing commitments [90]. Staff who feel their job is insecure, feel unsupported or mistrust their organisation or service are also less open to innovation and change; feeling they have little choice about whether or not to adopt an innovation erodes their goodwill [86, 90].

When children’s social care goes wrong, you know, kids can die… (that’s) why there might be some trepidation around innovation … because the stakes are high and they care about the kids and because you know it is going to be their name in the paper. (P11)

This was thought to have created risk-aversiveness, with managers reluctant to try ‘imaginative and bold’ new approaches (P9), even where it was clear that standard systems were not protecting children [65, 73]. Where a developmental, incremental learning process is placed at the core of implementation, rapid reflexive loops of ‘stop and think and pause and reflect and interrogate and review and revisit’ (P9) facilitate responsive adaptation within a rapidly moving field [51–53, 76, 85]. A strong and supportive leader or leadership team, which models relational and consultative practice, can stimulate creativity and instil the kind of trust in the system that enables staff to be ‘brave enough to do this stuff’ (P7) [46, 49, 64].

Collaboration across organisations harnesses diverse forms of expertise, power, reach and resources, but brings its own challenges. Divergence in epistemology, politics and values between policymakers and statutory, voluntary and for-profit sector services, for example, may lead to different understandings of ‘the problem’, its proposed ‘solution’, funding priorities and conceptualisations of ‘participation’, ‘agency’, ‘vulnerability’ and ‘responsibility’ [45, 52, 84, 88, 91]. Establishing policies, structures and communication channels from the start can ensure roles and accountability are clear, language and values are shared, principles are understood, power relations managed, and procedures are complied with across the partnership [41, 46, 48, 49, 68].

4.5. The Macro Context

We’ve kind of gone into twenty first century social care work, but actually our legislation just isn’t quite there, it’s very outdated …Whereas if you look probably in things like the private sector, etc., companies move on very quickly. They kind of move with the times, don’t they, to make things happen. (P4)

The presence of stable political leadership locally and nationally [93], and commitment to innovation from local political and policy structures, were seen as lubricating the wheels of the innovation process [44], enabling new ideas to be more readily ‘taken up, whether or not the evidence fully supports them’ (P12). Cynicism was expressed in the literature and by interviewees about the extent to which politicians and heads of service would simply ‘move on’ from such agendas whenever ideology shifted, or it benefited their careers to do so—or indeed when there was a change of government, centrally or locally [68, 83, 91].

I do think it is really valid that at a time when Government have consistently, year on year on year, reduced resources both to services and to families themselves, have consistently failed to address rising levels of family poverty, have consistently failed to address under-resourcing of local services, we shouldn’t therefore be surprised when Government sponsored or endorsed innovation is met with some cynicism. (P9)

If you’re desperately trying to get like the ear of (the Government department), they aren’t going to be interested if we say, ‘well what we’ve got is like a twenty-year programme of quite, of gradual but very steady improvement’, they’re just not interested! So what you need to be able to say is, ‘in six months’ time, we’re totally restructuring our entire…’, and then they are like, ‘ooh that’s interesting’. (P16)

That case was still rumbling on, nine years later when I went back, there was still a memory amongst the professionals, some of whom hadn’t even worked in the system then … what you had was a defensive response, you know. And a paralysis around it as well… It’s a very difficult climate in which to generate innovation because people are naturally risk averse and defensive in those situations. (P6)

5. Discussion

Hartley and colleagues’ 2013 comparison of public and private sector innovation observed that the barriers to innovation in the public sector were well rehearsed in the literature, while its drivers were underacknowledged [96]. In the specific context of social work, Brown [83] noted in 2010 a lack of attention to learning from what had happened in innovations that struggled and how challenges might be addressed. Our study suggests that these tendencies remain pervasive in children’s social care. The difficulties of innovating in the current context were discussed at length both by expert informants and the literature within and beyond the United Kingdom. Proposed solutions were not only scant but had a tendency to focus more on how national government and other public bodies should address overarching social and structural problems (such as increasing public funding for social care, preventative work, community amenities and welfare benefits), rather than how local services might still find ways of innovating within a less-than-ideal context. While the former would, of course, be desirable—ultimately reducing some of the demand for services as well as easing service development and delivery [22, 23]—there is little to suggest that some of these macro barriers are likely to disappear anytime soon, in the United Kingdom at least. Innovation is argued to offer a potential framework for system and practice transformation so that public services are better able to address key social and relational challenges and improve service user experiences and outcomes. An important question raised by this study is the extent to which this potential can be achieved if the prevailing macrolevel economic conditions and social policy discourses continue to be less than conducive.

While much of the literature and interview narratives focussed on how the technical activity of system or practice change might be facilitated, or how organisational efficiencies and service outcomes might be improved, clear voices emerged from both providing a reminder of how an important aim of social innovation is to ‘trouble’ and re-envision the very nature of social care systems, the philosophies which underpin conventional practice approaches, and the outcomes they are intended to produce so that they reflect both what children, young people and families themselves want, and the core values of social work [97]. ‘Tinkering about at the edges’ of current approaches with technical system ‘fixes’ or ‘bolt-on’ additions to practice methods, such as is more common with continuous improvement measures, were recognised by some critics as too insubstantial to address the scale of the challenges in the social care field which have been highlighted in this paper. Innovation, then, becomes an imperative where current systems need the kind of radical change that practice improvement measures cannot achieve within a less-than-optimal policy, regulatory and resource environment. Policies, cultures, structures and underlying paradigms all need to be challenged if child-focused, rights-centred, relational and inclusive practice is to be achieved as a step towards improving outcomes in ways that matter for children and families [95]. Even where the pertaining macro systems and resource constraints impede radical and transformational visions from being readily actualised at a local level, a strong case may still be built that energises practitioners, leaders and families alike to construct a powerful theory of change that garners sufficient powerful buy-in of the type that can shift policy and resource deadlocks.

None of the enablers identified in this study are surprising, and this was shown in the high degree of consistency across the interviews and international literature. However, identifying the enabling factors is only half the battle, as some of the generative mechanisms, powers and tendencies that influence where, how and why innovation unfolds in particular places, at particular moments, in particular ways, to achieve particular effects, may be hidden or hard to discern [98]. What the literature review and interviews were able to surface were some of the varied forms that enablers may take in different contexts and when applied to different kinds of model, population, place and so on, and the diverse implications where certain parameters were weaker or toxic.

This led us to consider that the conditional parameters are interdependent and intercontextual, and it is in their dialogue that their effects are most powerful, for better or worse. In particular, the conditional parameters set out in the ‘organisational culture, climate and processes’ cluster (outlined in Section 4.4) stood out to us as operating in a multi-influential push-and-pull manner to produce substantial and ‘complexly codetermined’ [99] impacts within each context in ways that often seemed to lie outside surface awareness and scrutiny and, hence, were often not well recognised or understood. We borrow here Glisson’s definition of ‘culture’, as being produced through ‘behavioural norms and expectations that … direct the way employees in a particular work environment approach their work, specify priorities, and shape the way work is done’ [100]. Glisson and colleagues found innovations were most likely to flourish in organisational cultures where: staff were provided with relevant knowledge and skills; there was less rigidity and bureaucracy regarding rules and procedures; and where resistance was lowered because staff had more discretion to be flexible, creative and responsive to service user need [101]. In contradistinction, organisational ‘climate’ was thought to be generated through ‘employees’ shared perceptions of the psychological impact of their work environment on their own personal well-being and functioning’ [100]. The best outcomes and highest service quality were found where staff felt more fully engaged in their work with service users, understood their role, found the work personally meaningful and received optimum levels of support and cooperation; in such organisations, role overload, role conflict and emotional stress and exhaustion were less likely, and employee turnover was lower [101].

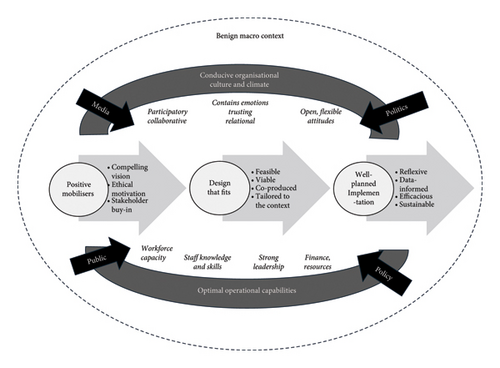

Taken together with our findings, it can be seen that innovation is best facilitated by a stable, well-supported workforce that feels energised and confident to create and implement change—but this type of conducive culture and climate can only happen where (1) the emotional dimension of change is recognised as a valid and normative process that requires containment and sense-making, rather than seen as a problem to be managed rationally [102], and (2) where organisational and professional learning is structured to be reflexive, developmental and nonjudgemental [103]. In such an environment, the psychological and practical burdens and consequences of risk-taking are borne and mediated by organisations and systems rather than individuals [56]. Formal planning processes of checks and balances can reassure staff that new approaches comply with legal and governance requirements and existing commitments will not drift out of sight [42, 85]. However, attention to developing a supportive, collaborative, relational culture of mutual trust, where reflexive supervisory and evaluatory mechanisms follow the human-centred grain of professional practice and where staff feel safe to experiment and make mistakes, is perhaps most important in managing anxiety and sharing responsibility for risk amongst those involved in the process [41, 43, 81, 93]. Where these conditions are all in place, this can start to open up a more ‘conducive zone’ for innovation (see Figure 1).

6. Limitations

While the academic literature included in our review derived from a number of countries, the majority of the grey literature and expert informants were situated within the United Kingdom. Hence, while our findings have direct transferability to social care policy and practice in the United Kingdom, their relevance for innovation practice in countries with a similar conceptualisation of child welfare and safeguarding needs careful contextual consideration.

The focus of our review was to investigate the processes of innovation in children’s social care and therefore the literature search protocol excluded studies from the social innovation, implementation science and organisation studies fields where they concerned change processes in other settings, such as health. While this has limited the insights that might have been gained from those wider literature, given the importance of contextual factors within innovation journeys that was highlighted by our study, we would suggest that this decision was justifiable.

7. Conclusion

The five clusters of conditional parameters found through this study to exert significant influence on innovation activity do not offer a ‘checklist’ for successful innovation but rather indicate an interrelated and coinfluencing web of conditions that have the potential to create a more conducive zone within which innovation can mobilise, embed and flourish, rather than an environment that challenges and impedes it. Innovation is, by its nature, an uncertain, resource-hungry endeavour and these factors can play out in diverse, unpredictable and often hidden ways, depending on how contextual factors influence their interaction and the extent to which the innovation design has accounted for these through each stage of the innovation journey. Rigorous research is now needed into the interplay of these conditions within children’s social care systems and partnerships across various geographic and demographic contexts.

Some critical voices emerging in this study have signalled the dangers that a government-fed fetishisation of novelty, market mechanisms and high-stakes competition for restricted finance can pose to the establishment of the kind of supportive, open and relational cultures that facilitate creativity, risk-taking, collaboration across services and mutual learning from experience. Where outcomes are connected solely to profit margins, innovation goals may start to diverge substantially from a solely welfare-oriented mission and even result in potentially harmful unintended outcomes [44, 47, 88, 92]. Consultation and coproduction with those children, young people and families most in need of new service approaches is arguably best placed to interrogate the aims of an innovation [69]. However, such collaboration remains work in progress. As some interviewees took pains to point out, critiquing the limited nature of ‘genuine’ coproduction in innovation work, is not to downplay how children and adults experiencing significant marginalisation, trauma and social stress may lack the time, energy or motivation to be involved in collaboration, but rather to emphasise the importance of starting with flexible, relational and creative methods of consultation that are built around the needs, lives and preferences of those people affected by new service designs. As this is resource-intensive, it does need to be realistically accounted for in innovation budgets and timelines if it is to be both ethical in its process and successful in its outcomes [14, 104].

Disclosure

The views expressed are those of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was made possible by grant ES/T00133X/1 from the Economic and Social Research Council in the United Kingdom.

Endnotes

1Here defined as statutory or voluntary (nonprofit) sector services directed towards the care, protection or social or emotional support of children, young people and families.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The interview data used to support the findings of this study cannot be made available for reuse as participants were given assurance that their data would be used only for this study. The rationale for this was that participants were describing interventions and system approaches that could make them, or their service, recognisable were the transcript to be viewed as a whole. Such potentially identifying details have all been removed prior to publication. This was also the process agreed with the funder and with the (Social Sciences and Arts) research committee at the University of Sussex.