How Does Living in a Homeless Hostel Impact on Residents Lived Experience of Health and Wellbeing: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Living in a homeless hostel can be challenging. This global scoping review explored the impact of living in a homeless hostel on residents lived experience of health and wellbeing. A systematic process was followed using Arksey and O’Malley framework for scoping reviews with the addition of the PRISMA-ScR checklist. In total, 1094 articles were identified through database searches and a thesis search on Google Scholar. Screening of title/abstract and then full text, according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulted in 40 papers being included in the review. Twenty-two were carried out in the United Kingdom (UK), nine in the United States (US), four in Australia, two in Canada, one in South Africa, one in Iran and one study had a worldwide focus. The findings identify difficulties in accessing care along with incidences of discrimination, being dismissed, disrespected and other experiences of stigmatic encounters. Survival tactics and coping strategies like drug and alcohol use were employed. A lack of stability and routine added to the challenges of living in that environment. The hostel itself and the experience of homelessness were found to impact on health and well-being. This review demonstrates a picture of disadvantage, discrimination and increased disease within the populations who reside in homeless hostels. More research is needed on lived experiences of those residing in homeless hostels to understand their experiences and inform the creation of environments more conducive to good health and wellbeing.

1. Introduction

Homelessness is a global phenomenon. In 2021, it was estimated that 140–150 million people were homeless in the world [1]. In the same year, more than 122,000 people were homeless in Australia [2], 582,462 people were without a home on a single night in January 2023 in the United States [3], while homelessness statistics hit record levels in England with 104,510 people registered as living in temporary accommodation [4].

The definition of homelessness varies around the world [5] and is a challenge to define [6]. Most definitions include living on the streets, in cars, temporary camps, in unsafe, inadequate or insecure housing and those living in temporary accommodation like hostels [7]. Globally, approaches to homelessness differ. In the United States, there is an explicit plan to end homelessness as setout in ‘All In’—a roadmap for crisis support, housing and prevention [8]. In Japan, which has seen a 12% reduction in homelessness since 2018, the focus is on making it very difficult and socially unacceptable to be homeless, by criminalising begging and ensuring street infrastructure does not facilitate sitting or sleeping out. In the United Kingdom, the approach to homelessness is heavily reliant on temporary shelter and hostels [9]. Many of the homeless hostels are run by charities and specialist housing associations with local authorities commissioning hostels to work with some specific groups [10]. In many countries, including the US and UK, homeless people will be placed in a hostel at some point in their homeless journey. On a single night in 2022, 20,071 people were estimated to be living in a homeless hostel in the UK [11], and the US recorded 327,000 people living in shelters from 2018 to 2022 which demonstrated a considerable increase from previous years [12].

Homeless hostels and shelters have a long and varied history. In New York City in 1734, the first poor house (homeless shelter) was opened. During the Victorian era in London, the workhouse system was established to provide work and housing to the poorest people [13]. In Australia, boarding and lodging houses met the demand in the 18th and 19th century [14]. Hostels were developed initially to meet the basic need for physical shelter but have evolved to offer support to people with increasing levels of complexity and difficulties including substance misuse [15].

It is recognised that homeless hostels can be challenging places to reside [16] with impacts on health and wellbeing. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ [17]. People experiencing homelessness often have very complex health problems including tri morbidity which is a combination of mental health, physical health and substance misuse problems [18]. Death rates among homeless populations are high, and the average life expectancy is low. In 2021, in England and Wales, the mean age of death for a man who is homeless was 45 years and 43 years for a woman [19]. The deaths were attributed mainly to substance misuse, suicide, accidents and cardiovascular disease [20].

Wellbeing is widely acknowledged to be a multidimensional concept [21]. Definitions abound including at its most simplistic ‘the state of being comfortable, healthy or happy’ [22]. A balance between the person and their environment has been shown to be intrinsic to achieving wellbeing. Having a secure home helps people develop self-identity and confidence [23]. The impact of housing beyond its material properties as valuable in terms of health has long been recognised [24]. For people facing homelessness, as their health deteriorates, their options reduce [25], and they can end up in unsuitable hostels, with inadequate care and facilities. Moreover, drug and alcohol use may be rife within many homeless hostels [26, 27]. These concerns have given rise to the introduction of a harm reduction approach which aims to minimise the negative impacts on health and wellbeing [28]. Harm reduction or harm minimisation was founded in the Netherlands in the 1970s [29, 30] encouraging treatment and can help facilitate homelessness services to work with people in a positive way, keeping the users in contact with drug services [31] with or without abstinence [16]. The application of harm reduction varies globally but typically includes needle and syringe programmes, opioid agonist therapy, drug consumption rooms and safer smoking kits [32].

Another approach achieving global attention is the housing first approach which was developed specifically to address the housing needs of people with substance use disorders and mental illness without adherence to substance replacement treatment/abstinence. The aim is to invest in building homes and ensure that people are helped into housing quickly. A housing first policy in Finland, with the priority being to ensure permanent rental accommodation, is built and available and has led to a decrease in homelessness [33].

Homelessness is a severe form of social exclusion [34] and can have a very detrimental effect on peoples’ health and wellbeing [35]. Homeless hostels with or without harm reduction approaches have limited success in providing adequate housing to people living with complexity. Many homeless people chose to sleep rough rather than tolerate the challenges presented to them in homeless hostels that purport to have been setup to meet their needs. This scoping review will explore the literature on living in homeless hostels. The aim is to ameliorate understanding of the lived experience of residents and the impact on their health and wellbeing. To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to explore the literature on the lived experience of living in a homeless hostel and the impacts on health and wellbeing.

2. Methodology

This scoping review aimed to explore both grey and published academic literature to get a broad oversight of the lived experience of residents in homeless hostels and the impact on their health and wellbeing [36]. A scoping review aims to use both a systematic and iterative approach [37] to establish gaps in a wide range of literature [36]. Arksey and O’Malley’s [38] framework for scoping reviews was utilised as well as the PRISMA-ScR checklist [39] to ensure a systematic approach (please see supporting file for PRISMA-ScR checklist (available here)). This scoping review was registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/fr28u/).

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

-

P (types of participants): residents

-

C (concept): experience of health and wellbeing

-

C (context): homeless hostel

The resultant question for the scoping review was as follows: how does living in a homeless hostel impact on residents lived experience of health and wellbeing?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

With an emphasis on identifying all relevant publications, including grey literature, we (EH/JM) first searched the following nine electronic databases through EBSCOhost: Academic Search Premier, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, APA PsycArticles, AMED—The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, SPORTDiscus with Full Text and eBook Collection. This search was conducted on 30th June 2024. No limiters were applied. Please see Table 1 for keywords.

| “wet hostel∗” OR “wet house∗” OR “wet hotel∗” OR hostel∗ OR “homeless hostel∗” OR “wet shelter∗” OR “multiple complex need hostel∗” OR “halfway house∗” OR “homeless shelter∗” OR “Emergency and transitional shelter∗” OR “Emergency Shelter∗” OR “high risk homeless hostel∗” |

| AND |

| “lived experience” or “phenomenolog∗” or “life experience” or “experience” |

| AND |

| “health or wellbeing” or “mental health” or “illness” or “physical health” |

An additional search for grey literature such as theses and other publications was undertaken using Google on 28th July 2024. Backward and forward searching of the reference lists of identified articles was also undertaken via Google.

2.3. Stage 3: Study Selection

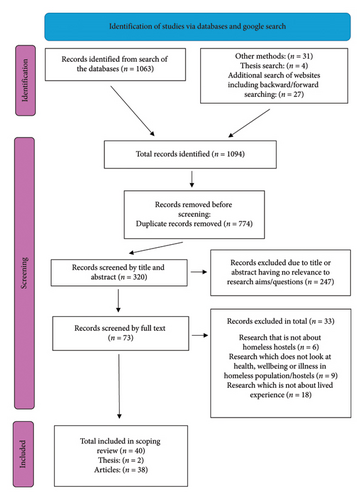

The search in EBSCOhost identified 1063 papers. The additional backward and forward searches and other searches in Google found 27 papers and 4 theses. In total, 1094 articles were transferred to Endnote, and duplicates were removed (n = 774). The remaining 320 records were assessed for eligibility by screening the title and abstract according to exclusion and inclusion criteria (please see Table 2). The screening was undertaken by EH/JM.

| Inclusion criteria: |

| • Text in English |

| • No defined date |

| • Primary research on lived experience of health or wellbeing in a homeless hostel |

| Exclusion criteria: |

| • Full text not available |

| • Texts in other languages other than English |

| • Research that is not about homeless hostels/shelters |

| • Research which does not look at lived experience of residents in homeless hostels |

| • Research which does not look at health, wellbeing or illness in homeless hostels |

| • Research that is about other types of hostels (i.e., backpackers’ hostels). |

After screening of the abstract and title according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 247 articles were excluded due to lack of relevance to the research question. The remaining 73 articles underwent full-text reading and were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirty-three articles were excluded, resulting in 40 articles/theses in the final scoping review. Please see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flowchart.

In line with the aim of a scoping review to elucidate the depth of a subject area [41] and provide an overview of the available literature on living in a homeless hostel and the impact on residents’ health and wellbeing, this study does not include a critical appraisal of the quality of the literature [38].

2.4. Stage 4: Charting the Data

The data from the published articles were extracted manually and presented in an excel spreadsheet with the following detail: author/date, research aim, research design, research methods, sample/setting/where recruited/country and main findings. The data from the four theses were extracted into an excel database using a template designed for grey literature with the following headings: setting, specialist topic, study population, sample size, study results, barriers, facilitators and limitations [42]. E.H. extracted the data which was checked by J.M. In total, data from 40 articles/theses were extracted.

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse the data (E.H./J.M.) following the six steps [43]. The extracted findings were coded line by line, by hand by E.H. and checked by J.M., to identify common phrases and words; these individual codes were then combined to inductively generate four themes. The paper reports the results by exploring the methodologies of the 40 articles/theses before continuing onto to discuss the identified themes. The last part of the paper discusses the findings and gaps in the research literature.

3. Results

Forty papers were identified. Of these, 33 were qualitative studies, two quantitative, 4 mixed methods and 1 was a literature review. Two of the studies were produced by PhD students, and the rest were published by academics. Only one was published prior to the 21st century. Homeless hostels were featured in each with a particular leaning towards encompassing both residents and staffs’ views on lived experience.

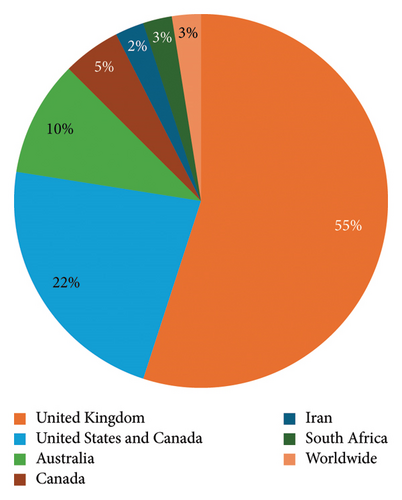

Twenty-two of the studies were carried out in the United Kingdom, nine in the United States, four in Australia, two in Canada, one in South Africa, one in Iran and one study had a worldwide focus. Table 3 provides an outline of the literature whilst Figure 2 summarises the location of the research.

| Author/Date | Aim | Research design | Research methods | Sample/setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong et al. 2021 | Identify barriers and facilitators to accessing health and social care services for people living in homeless hostels. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Analysed thematically. | 33 participants; 18 homeless hostel managers/support staff and 15 people experiencing homelessness, from six homeless hostels in London and Kent, UK. Residents were mainly men, staff were mainly women. Predominantly White British. |

| Bark et al. 2023 | To understand and make recommendations to improve cardiovascular disease care in homeless populations through lived and professional expertise. | Qualitative | Focus groups. Thematic analysis. | Convenience sampling. London and the Southeast of England, UK. Four focus groups were conducted with people currently or previously experiencing homelessness and a cardiologist, a health services researcher and an ‘expert by experience ‘. The three groups included 16 men and 9 women, aged 20–60 years, of whom 24 were homeless and currently living in hostels, and 1 rough sleeper. |

| Bazari, 2018 | To characterise the experience, understanding and management of physical, psychological and social symptoms among older homeless adults. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Longitudinal study. Thematic analysis. | Aged 50 plus. Purposive sampling. Oakland, California, USA. From overnight, homeless shelters and low-cost meal programmes and other places where unsheltered people stay. 20 participants. Most (85%) were African–American; 65% were men; and the median age of participants was 62 years old, with a range of 52–78. |

| Chaturvedi, 2016 | To ask homeless young people who had accessed counselling what they thought were the main barriers to counselling and how they could be overcome. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis. | Carried out within a homelessness charity in the United Kingdom, where the researcher works as a psychotherapist. Young people who had accessed the organisation’s counselling service between April 2013 and June 2014, attended at least two sessions of therapy and were not currently undergoing therapy were included. 7 in total, five female, two male. 16–25 years. Participants residing in hostels. |

| Collins and Freeman, 2007 | To assess the oral health needs of a homeless population in order to determine the levels of unmet need. | Mixed methods | Medical history questionnaire and a questionnaire to assess health and psychosocial needs, dental anxiety and oral health–related quality of life. Oral examination. Quantitative analysis. | Fourteen hostels in north and west Belfast, United Kingdom. Snowball sampling. 317 people. Two hundred and sixty-seven (84%) male from 16 years to 91 years. The mean age was 39.6. |

| Dawes et al. 2022a | Exploring how the pandemic affected homeless people. | Qualitative | Semistructured qualitative interviews. Reflexive thematic analysis. | UK wide. People experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic and service providers. 18+. Homeless participants were aged 24–59 years, and service providers were aged 34–53 years. Interviews = 33. Equal distribution of men and women, predominantly White British. All had lived in hostels or hotels, with friends or family or on the streets during the pandemic. |

| Dawes et al. 2022b | How did the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing restrictions impact the health, wellbeing and provision of services for homeless people. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Reflexive thematic analysis. | 22 interviews with people who experienced homelessness during the pandemic and 11 with homelessness sector service providers. People experiencing homelessness, 11 (50%) were female, 13 (59%) White British, and all were aged between 24 and 59 years, and all had lived in hostels or hotels, with friends or family or on the streets during the pandemic. |

| Gilkey, 2009 | Experience of being homeless. | Qualitative | Conversational style of interviewing. Narrative analysis. | Shelter. Pittsburgh, USA. Convenience sampling. 25–59 age range. 20 residents. 16 men, 4 women. |

| Guise et al. 2022 | Sought a community level perspective to explore relationships between COVID-19 and existing health inequalities. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. An inductive and deductive approach to thematic analysis was used. | Purposive sample of 17 (5 women, 12 men) people experiencing homelessness and 10 people working in outreach and hostel settings in London, UK. |

| Hammersley and Pearl, 1996 | To find out the experiences of homelessness in young people using the services of two projects. | Mixed methods | Semistructured interviews including standard psychological test items and others. Thematic analysis and tables. | Two projects housing young people in Glasgow, UK, with varying degrees of vulnerability were used. 59% of the residents were interviewed. 56 men, 44 women between 16 and 30 years. 100 semistructured interviews. |

| Holmes, 2007 | To explore the experience of homelessness in Darwin. | Qualitative |

|

Darwin, Australia. 10 key informants. All were Australian citizens. Nine [8] were male and one [38] was female. House, meal and shelter service. |

| Hubbert, 2005 | To explore the subculture of homeless adults residing in one shelter. Experience of care. | Qualitative | Ethnographic study. Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis. | Nebraskan (USA) urban homeless shelter. 9 resident participants. 20 staff participants. Christian with clergy and volunteers and weeks of support and counselling. |

| Hudson, 2016 | To provide a deeper understanding of the challenges to and suggestions for palliative care access and delivery for homeless people by synthesising qualitative studies exploring palliative care from the perspective of homeless people and the professionals supporting them. | Literature review |

|

Worldwide in total, studies represented the views of 98 homeless people, 38 hostel staff, 14 outreach workers and 103 health and social care professionals (most in USA or Canada, others are Sweden, UK and Australia). |

| Irving 2018 | To gain insight into the meaning of trauma within the lived experience of homelessness. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). | Purposive data sampling White British with their age range spanning 19–56 years and 23 local stakeholders. Private hostels in Southampton, UK. |

| Johari et al. 2022 | To explain the lived experiences of homeless youth in Southeastern Iran. | Qualitative | In-depth and semistructured interviews and three focus group discussions. Data analysed by conventional qualitative content analysis. | 13 participants in a big city, Southeast Iran, in 2020. The participant was young homeless adults aged 18–29 years who were using homeless shelters provided by the municipality, sleeping in parks or on streets. Mostly men. |

| Jonas, 2009 | How homeless African–American mothers and their children defined their health in emergency homeless shelter. | Qualitative | Grounded theory. Semistructured interviews analysed with substantive and theoretical codes. | Midwestern city, USA. African–Americans young women (late teens, twenties) with children in a homeless shelter. 15 participants. |

| Karim, 2006 | To learn more about the short- and long-term psychosocial outcomes of homeless children and their parents. | Mixed methods | Validated questionnaires including Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Eyberg Child Behaviour, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents), (Parenting Daily Hassles Scale). | UK-wide - homeless families in hostels. Thirty-five homeless families. Assessed following admission to two homeless hostels, and 4 months later, when most families (69%) had been rehoused |

| Long and Jepsen, 2023 | Contribution to the existing literature on stigma by comparing the stigma management strategies of those in active drug use and recovery and by using this to highlight the importance of ethnography within this field. | Qualitative |

|

Data drawn from two ethnographic studies. One set in a male only homeless hostel in the south of England, UK, and the other at a substance use service in South Wales, UK. Participants were members of these communities. Observations = 218 h and 17 semistructured interviews with current residents and members of staff and creative timeline interviews with former hostel residents. Participant observation was accompanied by ‘photo elicitation’ conversations with several male members of the service (n = 7). |

| McMordie, 2020 | Explore lived experience of hostels in Belfast. Draws upon data from a study. | Qualitative | Cognitive appraisal theory. Life history methodology interviews. Transcribed and coded using inductive approach. | Belfast, UK. All adult male (n = 8) many with complex needs—accessed at a temporary accommodation. |

| McGrath and Pistrang, 2007 | To find out more about dilemmas in working with homeless young people in the United Kingdom. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews were conducted. Analysed using the method of interpretative phenomenological analysis. | Central London, UK. The hostels were targeted at ‘vulnerable and disadvantaged’ homeless 16- to 25-year-olds. 12 residents participated in the study, seven female and five male: (range 16–23). 10 staff, six female and four male; their average age was 32 (range: 19–52 years). |

| Meehan, 2023 | Homeless shelter residents’ receipt of healthcare, care experiences, perceptions toward healthcare. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews utilising purposive sampling and focus group discussions. Thematic analysis. | 6 homeless shelters in Seattle-King County, Washington, USA, during July–October, 2021. All residents (age ≥ 18) were eligible to participate. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 25 residents, and 8 focus group discussions were held. |

| Moore, 2000 | Qualities of home and their potential value in the promotion of wellbeing are discussed. | Quantitative | Literature review | Examined the concept of home within western society |

| Mphigalale, 2021 | Explore experiences of homeless young women aged from 26 to 35 years in Cape Town about their perceived wellbeing. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis. | 10 women from the shelter. The ages of participants ranged from 26 to 35 years. South Africa. |

| Motta-Ochoa et al. 2022 | The findings of an attempt to integrate the knowledge of people experiencing homelessness and alcohol dependence into the design of indoor alcohol use service. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews and focus groups. Thematically analysed. | Montreal, Canada. wet service. 34 participants. The eligibility criteria were [38] not having a fixed address over the last 12 months [1], being engaged in heavy alcohol drinking [2], being aged 18 or older, (49.4 years old; range, 24–71 18 men; 13 women; 3 nonbinary. Wet housing services. |

| Odoh, 2020 | Examine the associations between fear, mistrust, and fear and mistrust and stress among sheltered homeless adults. | Quantitative | Fear and Mistrust Scale and the Urban Life Stressors Scale | Convenience sample of adults from a homeless shelter in Dallas, Texas, USA, (N = 225; 67% Black; 27% women). 18+. |

| Phipps et al. 2017 | To examine the experiences of residents and staff living and working in a Psychologically Informed Environment (PIE). | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis with a phenomenological epistemological approach. | 9 residents—46–55 age category, 10 staff but two were male. 26–46 age groups; Five therapists took part based in London, UK. |

| Pope, 2020 | Understand the return path to homelessness. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews and thematic analysis. | 18 men aged 50 and older, who had experienced multiple instances of homelessness. Homeless day centre located in a Midwest USA metropolitan city, 25 participants. Discuss living in a residential shelter. |

| Pratt, 2019 | Explore the impact of the social environment on smoking cessation for smokers experiencing homelessness. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews and thematic analysis. | Forty participants (11 female; 29 male) at 2 urban homeless shelters in the upper Midwest, USA. |

| Rae and Rees, 2015 | To understand the perspective of the homeless about their healthcare encounters and how their experiences of receiving healthcare influence their health-seeking behaviour. | Qualitative |

|

Two women and 12 men were interviewed from two local homeless services: one hostel for men and one nonresidential facility for male and female homeless UK wide. |

| Rapaport et al. 2023 | Exploration of how stakeholders understand memory problems among older people in the context of homelessness and consider what they judge gets in the way of achieving positive outcomes. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Reflexive thematic analysis. | Semistructured interviews. 17 older people who self-identified as having memory problems, 15 hostel staff and managers plus 17 health, housing and social care practitioners. UK wide. |

| Shulman et al. 2018 | To explore the views and experiences of current and formerly homeless people, frontline homelessness staff and health- and social-care providers, regarding challenges to supporting homeless people with advanced ill health. | Qualitative |

|

Single homeless people (n = 28), formerly homeless people (n = 10), health- and social-care providers (n = 48), hostel staff (n = 30) and outreach staff (n = 10). Three London boroughs, UK. |

| Sleed, 2013 | Assess whether a pilot baby clinic in a hostel for homeless families to address the specific attachment and developmental needs of infants living in temporary accommodation. | Mixed methods | Evaluation. 30 mothers and babies in the intervention hostel group and 29 living in comparison hostels. Infant mental and motor development was assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. Interactions between the parents and infants were video-recorded and coded on the Coding Interactive Behaviour Scales. | Fifty-nine mother–baby dyads. The mothers’ mean age was 25 years in the intervention hostel group and 27 years in the comparison group. The child mean age was 7.5 months in the intervention hostel and 9 months in the comparison group. London, UK. |

| Stambe, 2024 | Study the experience of living in a repurposed hotel for homeless people. | Qualitative |

|

Hotel for people experiencing homelessness located in Southeast Queensland, Australia. 276 in sample, 73% male, and 27% female. |

| Sturman and Matheson, 2020a | To explore client experiences of, and attitudes to, community-based healthcare. | Qualitative | Focus groups in an inner-city homeless hostel. Analysed thematically. | Hostel for homeless men in South Brisbane, Australia, with a total of 20 men (aged 28–58 years, mean age 43). |

| Sturman and Matheson, 2020b | To understand the perspectives of marginalised groups (homeless). | Qualitative | Focus groups. Transcript inductively coded. | 20 male clients. Client ages ranged from 28 to 58 years (mean age 43 years). Brisbane, Australia. Discuss living in a hostel. |

| Sznajder-Murray and Slesnick, 2011 | Gain a better understanding of homeless mothers’ perceptions of service providers. | Qualitative | Focus groups. Thematic analysis. | 28 mothers residing at a homeless shelter in Midwest, USA. African–American (60.8%), 32.1% were White and 7.1% reported mixed ethnicity. 18 to 40 with an average age of 29.2 years old. The mothers had an average of 3.1 children. |

| Tischler et al. 2007 | Describe mothers’ experiences of homelessness in relation to their mental health, support and social care needs. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis was used, applying both deductive and inductive coding. | Twenty-eight homeless women with dependent children in Birmingham, UK. Median age of 36. Caucasian (n = 14, 50%), the remainder were Afro-Caribbean (n = 7, 25%), Asian (n = 4, 14.3%) or Middle Eastern (n = 3, 10.7%). Living in hostel. |

| Warren et al. 2021 | Experiences and perceptions of clients within the homeless shelter. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Thematic analysis. Phenomenon–logical. | Southeast England, UK. Six participants living in homeless hostel. |

| Wright et al. 2005. | To explore the relationship between housing status, associated social networks and risk factors for heroin-related death. | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews. Analysed thematically. | In the UK northern city, the setting comprised three centres providing services to homeless drug users. 19 men and eight women. All respondents were White Caucasian. The age range was 21–58 years. Range of accommodation. |

| Young and Manion, 2017 | This research examines the effectiveness of an emergency warming centre (EWC) of morbidity and mortality for homeless persons with concurrent disorders (mental health problems and addictions). | Qualitative | Semistructured interviews and focus groups at two points in time within a symbolic interaction framework. Critical analysis. | Western Canadian Arctic, however, unlike the permanent homeless shelter in inuvik, the EWC was accessible to people who were under the influence of drugs or alcohol. |

4. Main Findings

The following provides a summary of the themes found across the 40 articles.

4.1. Difficulty Accessing Care

The challenge of accessing care in this cohort is multifactorial. A worldwide systematic review of the literature aiming to comprehend better the challenges to accessing palliative care for homeless people revealed some barriers. The review encompassed the views of 98 people experiencing homelessness (PEH), 103 health and social care staff and 14 outreach workers [44]. Both staff and residents reported finding it difficult to get support from appropriate services and cited a lack of communication and responsibility [44]. This was aligned with the apparent ‘invisibility’ of general practice which was raised in an Australian study of men’s experiences of living in a homeless hostel [45]. Similarly, a UK-wide qualitative study based on two hostels providing alcohol and drug rehabilitation found from analysis of semistructured interviews of hostel residents that they had difficulty registering with services such as a general practitioner (GP) and travelling to get to services [46]. A study of residents of six homeless shelters in the US city of Seattle found an absence of communication regarding care availability and difficulty in accessing care [47]. Another study ran as part of a pilot model introducing palliative care experts into six homeless hostels in Kent and London, UK, ascertained from both staff and residents that PEH rarely gain access to palliative care and experienced insufficient responsiveness from healthcare services [48]. A qualitative study looking into the experiences of staff and homeless people with advanced illness in three London boroughs in the UK produced similar findings [49].

In a study using in-depth and semistructured interviews to explore the lived experience of young homeless people in Iran, the inability to access healthcare was reported in addition to inadequate support to meet their basic needs [50]. A study of US homeless mothers found that there was dissatisfaction with the support provided. The mothers felt that the lack of guidance to access services demonstrated a lack of care or willingness to help them [51]. Difficulty accessing services that provide care was also noted in a UK-wide qualitative study using semistructured interviews and reflexive thematic analysis investigating how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted homeless people. A move to online services and remote access increased the access difficulties experienced by the 33 predominantly White British participants [52]. Furthermore, in an ethnographic study based in a homeless hostel in Darwin, Australia, a lack of treatment options were barriers to care [53]. A lack of choice was also noted in a study using focus groups and interviews to elicit the views of homeless people and staff members managing significant health conditions [49]. A worldwide systematic review of palliative care delivery to homeless people found a pattern of care avoidance and resultant late presentation to healthcare services and that people were being given inadequate analgesia [44]. In addition, a study of young people living in homeless hostels in Glasgow in the UK found a high rate of health problems with extensive use of services [54]. In contrast to the abundance of reports of difficulty accessing services, the evaluation of a model adding palliative care staff into homeless hostels found good links with external health and social care agencies [44].

Fragmentation of care [55] and the absence of coordination between services such as health and housing [56] were cited as obstacles for PEH accessing care. Alongside this, the importance of establishing links with agencies [48] and the benefits of having services available on the premises [57] and accessible interventions [58] with a person-centred approach [57] were introduced as solutions to this problem.

4.2. Stigma

More than half (55%) of the literature mentioned stigma of various forms in association with resident’s experience of their own health and accessing healthcare. A qualitative study in the UK asking young people in a hostel about the barriers to receiving counselling found that they felt let down in the past and felt concerned about how they are perceived by others [59]. Hudson et al.’s [44] worldwide systematic review of palliative care in a homeless hostel environment, including the views of staff reported poor experiences of healthcare and incidences of discrimination and disrespect [44]. A longitudinal study conducted over 1 year, of homeless older adults based in California, USA, found feelings of a loss of dignity, shame, feeling demoralised and encountering stigmatising and dehumanising encounters with nonhomeless people [60]. A study in Seattle and another in Dallas, United States, revealed that homeless hostel residents felt discriminated against by the healthcare staff [47, 61]. Of note, it has been demonstrated that negative and positive encounters with healthcare can significantly impact homeless people and their future engagement with care [46].

The challenges presented to hostel residents in navigating stigmatising processes were highlighted as an influence on health [53]. Semistructured interviews were used to explore women’s experience of homelessness in South Africa and found that there were challenges in navigating relationships with staff, professionals and other residents [62]. Trust was also raised in a worldwide systematic review of qualitative research, with discomfort in hospitals and institutional settings presented as one of the causative factors [44]. An Australian study reported a scepticism of health professionals’ motives [45] and young homeless people in a UK study cited this as leading to resistance ‘opening up’ [59].

In a quantitative study, which utilised a questionnaire to assess the oral health needs of PEH based on 14 hostels in Belfast in the UK revealed marginalisation and social exclusion as features of the resident’s experience of healthcare. Social connectedness and loneliness influenced wellbeing [53]. This was also seen in a qualitative enquiry into young people’s experience of counselling where the interview data showed marginalisation as a feature of their experience [59]. In a study examining COVID-19 and health inequalities in outreach and hostel environments, it was noted that social distancing is the norm for many PEH [63] which aligns with a further UK-wide exploration of COVID-19 and its impacts on PEH acknowledging hostility from the public as a feature of their lived experience [52]. A further study looking at young people’s experience of homelessness in Iran revealed that the participants felt abandoned by society [50]. A study of mothers’ experiences of navigating health and homelessness in a Midwestern City in the United States described them as feeling like they were second class citizens [64]. Additionally, in a phenomenological study of clients’ perceptions of a homeless hostel in Southeast England they felt less than human and valueless when engaging in healthcare environments [65]. Notably, in a UK-wide qualitative study of homeless hostel residents using interviews and thematic analysis issues of poor self-worth were identified [52]. Another study of mothers parenting in homeless hostels reported avoiding getting help for substance misuse due to fear of being judged [51].

In a qualitative study of older people in the UK experiencing memory problems, which included findings from both staff and residents, it was reported that their concerns were misinterpreted, overlooked or not taken seriously by healthcare professionals [66]. A focus group–based study based in Brisbane, Australia, found that inadequate responses to psychological and physical pain were reported with dismissive care and limited knowledge of distress [67]. Furthermore, in a study based on London and the Southeast focussing on homeless peoples experience of cardiovascular disease care, four focus groups were thematically analysed revealing feelings of being stigmatised and being removed from hospital settings because of unprescribed drug use [68].

4.3. Suitability of Environment

The hostel environment has been found to have an impact on health and wellbeing, and this too is multifaceted. A qualitative study using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) based on a homeless hostel in the UK looked to gain insight into what trauma means to homeless people. It was found that the experience of living in homeless hostels had multiple impacts on people’s health [69]. Notably, it demonstrated that those people with the most complicated pathways into homelessness did not fare as well in the hostel environment and those who experienced less complex journeys into homelessness led reasonable lives within the hostel [69]. With the aim of understanding the path into homelessness using interviews of men over 50 years in a homeless day centre in a Midwest United States city, it was found that those people who had suffered trauma found it hard to function in a homeless shelter. They perceived the environment as physically and psychologically unsafe [70]. Residents experienced a lack of choice in the shelter they were housed in and a further lack of autonomy within the shelter [70]. Homeless adults in a shelter in Dallas in the USA found feelings of fear and mistrust and highlighted the impact of living in an environment perceived as unsafe [61]. Fear of infectious diseases from living in a shared space was documented in the grounded theory study of mothers’ experience of living in a US homeless hostel [51].

In a study of three homeless centres providing services to people using drugs, interviews were carried out to explore the relationship between risk factors for heroin related deaths, social networks and housing status. They found that the type of accommodation impacted the level of deaths and that different types of homeless accommodation had different cultures of drug use [71]. A study of a service setup to provide warm overnight shelter to people with addictions and mental health problems in Canada highlighted the importance of a safe place to stay [72]. A study in South Africa exploring the wellbeing of homeless young women cited safety as being experienced when shelter is provided [62]. Difficulty living with strangers in a hostel came up in a study of African–American mothers’ experience of health in a homeless hostel in a midwestern City in the United States, citing the challenges of parenting in that environment and following the rules [64].

The importance of constructing a sense of home was found to be of importance to PEH’s wellbeing [53]. In a mixed methods study looking at 531 adults experiencing homelessness and examining the home like qualities of the hostel, a relationship between wellbeing and the homelike qualities of a hostel was recognised [73]. A study with an aim to integrate people having experienced homelessness into the design of an indoor alcohol use service in Canada, also noted the value of helping to create a sense of homeliness [57]. Another article focused on data from a qualitative study looking at lived experience of 8 adult male residents of temporary housing in Belfast in the UK. It had a particular focus on why people chose to leave the accommodation offered and found that the choice to leave was rational considering the stressors and other demands presented by the hostel environment [74].

Similarly, a study was carried out that looked at hotels being used as homeless hostels during the COVID-19 pandemic in Queensland, Australia. It used ethnography and interviews to elucidate the experience of living in these environments and found that the individual space and moving away from large hostels had benefits for the residents and raised the importance of consideration of the built environment and effective service delivery [75].

In a study of 33 participants, including staff and homeless people, it was shown that the staffing situation had an impact on people’s experience of living in a hostel and on their health and wellbeing [48]. This study revealed staff shortages, staff burnout, lack of external support, staff burden and lack of staff training as issues which impacted on their ability to meet the needs of the residents adequately [48]. Similarly, in their UK-wide study of homeless people’s experiences during COVID-19, the pressure of working with homeless people and staff burn out were again cited as factors impacting lived experience [52]. A UK study encompassing both staff and residents’ voices with a focus on memory problems recognised that staff moved beyond the scope of their roles to advocate for residents [66].

The relationship between staff and the residents was also found to be of significance. In a phenomenological study based in hostels in Central London looking at the relationship between staff and residents a tension was revealed between the two, with the residents not being sure whether the staff were allies or not and the staff finding it hard to decide where they sat between providing support and enforcing rules [76]. It was acknowledged that the respect between staff and residents was important for good experience of hostel living [76]. The study of a wet service housing 34 PEH also noted the positive impact of effective key worker relationships with residents experiencing warmth, acceptance and trust [57].

The absence of appropriate hostels to care for people with high support needs including substance misuse was raised in a study of homeless people’s experiences in three London boroughs, with a particular focus on people with severe disease and advanced poor health remaining in hostels [49]. Homeless hostels were recognised as not having been designed as a place for care [44]. Residents reported feeling trapped and helpless [64].

While most of the literature reports the negative impacts of homelessness and hostel living on health and wellbeing, there were four that documented the positive outcomes. In a narrative enquiry of emergency shelter living in Pittsburgh, US, seeking shelter was seen as a way of escaping responsibility and finding a place where things could become more stable [77]. In a qualitative study of the culture of a homeless shelter run with a Christian philosophy with clergy and volunteers on hand to provide support and counselling the staff reported that the residents felt accepted with hope for the future [78].

4.4. Impact on Health and Wellbeing

Homeless people tend to die younger than people with stable housing [48] and can die in unacceptable and inappropriate situations [49]. The literature revealed difficulties engaging in healthy habits and maintaining healthy lifestyles. In a mixed-methods study on the experience of homelessness in young people, it was demonstrated that residents of hostels may teach each other worsening behaviours [54]. One focus group study comprising homeless people and professionals exploring cardiovascular disease and homelessness in London and the Southeast of England found several dysfunctional contributors to the health environment. These include unhealthy food, limited access to suitable food preparation areas, hygiene concerns, high rates of smoking and minimal awareness of the importance of exercise and a good diet [68]. A study conducted in Belfast in the homeless hostel population revealed high levels of poor oral hygiene and dentition [6]. Furthermore, a study based on a shelter in Darwin, Australia, noted the link between access to nutritious food and wellbeing [53].

Management of long term and acute conditions was also highlighted as a challenge in hostel environments. The environment was seen as a barrier to attending appointments, taking medication and general management of conditions [68]. Difficulty storing and administering pain relief in hostels were also seen in an international systematic review [44]. In a study of the impact of a psychologically informed environment in two hostels in London, UK, the impact on experiences of trauma on mental health was recognised [79]. This trauma before and during homelessness was also seen in a study in the US of homeless men over 50 looking at their path to homelessness [61]. In an exploration of homeless men’s experiences of homelessness and healthcare, there was a prominence of both physical and psychological pain [45]. This was supported by a study into the experiences of homeless mothers, where depression was common with a particular relation to the hostel environment and past trauma [55]. This was seen also in the study where the psychological impacts of ongoing and preexisting trauma were noted [53]. In the study of older adults based in Oakland, California, it was recognised that physical symptoms of illness were worsened by psychological distress [60].

The complexity seen with mental and/or physical illness with substance dependency was demonstrated in the literature. In a study of older adults over 50, using semistructured interviews, concerns around an increase in cognitive impairment were raised [66]. A qualitative study of the effectiveness of a warming centre in Canada raised the complex interplay between addiction, mental illness and homelessness [72]. Increased mental health needs were also seen in a mixed methods study looking into the psychosocial outcomes of homeless parents and children in the UK [56] with a deterioration in children’s behaviour while living in hostels. There was, however, reported improvement in children’s self-care, relationships and emotional problems [56].

An international systematic review of the literature highlighted the fact that homelessness and living in homeless hostels can be a life filled with fear [44]. It was also seen in a study exploring the relationship between existing health inequalities and COVID-19 that homeless people developed a numbness to suffering which meant that they were less likely to notice if they were unwell [63]. A chaotic lifestyle is part of the lived experience of homeless people [44] with which comes an inherent lack of stability impacting on ability to engage in healthcare [66].

4.5. Chaotic Lifestyle And Survival Tactics

With links to the previous theme, hostels were described as chaotic and dangerous in a qualitative study based in London, looking at both staff and residents’ perceptions [79]. A quantitative study of the oral health needs of residents of hostels in Belfast also noted a chaotic lifestyle [6] as did a focus group-based study including staff and residents in London and the Southeast of England [68].

The employment of survival tactics to cope with homelessness was recognised in the qualitative study of people working with the homeless and those experiencing it in the UK in a study looking at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [52]. In the qualitative study of homeless hostel residents in Darwin, coping mechanisms were used such as alcohol and drug use [53]. In a South African research study of young homeless women, survival took precedence over health and there was little motivation to change that [62]. A mixed methods study in Dallas, Texas, of adults in a homeless shelter found that the residents were reluctant to protect their health with a change in behaviour [61].

Drug and alcohol addiction was a common theme throughout the literature and seen by some as a way of coping. In a study of risk factors for a heroin-related death in a northern UK city, heroin was used to manage insomnia [71]. Use of alcohol and drugs to manage feelings of distress was reported in a year-long study of older adults in California [60], supported by a study looking at smoking cessation in the homeless hostel which reported people smoking to help manage stress [80]. Drugs and alcohol being used as coping mechanisms were seen to have an impact on cardiovascular disease management [68] with those using drugs seen to be not adhering to treatment [63]. In Glasgow, UK, approximately half the residents of the studied hostels reported being addicted to alcohol and or drugs [68], and in an exploration of palliative care repeated exposure to drugs was noted [44]. Additionally, an exploration of smoking cessation and how it is impacted by the homeless hostel environment was completed in two hostels in the upper Midwest US. The study found a prevalence of drinking and smoking in the hostel and that both are seen as important means of social interaction [80].

5. Discussion

This scoping review explored the health and wellbeing related experiences of residents living in homeless hostels. Four themes were identified that provided a summary of the experiences identified including difficulty accessing care, stigma, suitability of environment, chaotic lifestyle and survival tactics.

Harm reduction approaches have evolved to reduce risk and improve access to services and support, but this paper reveals a notable absence of coordination between these services [56] and fragmentation of care [55]. Perception of stigma and the impact on peoples’ experiences was seen throughout the literature [81] with homeless people feeling abandoned by society [50] and discriminated against by healthcare staff [47, 61]. Although having a safe place to stay [62, 72] has been seen to be imperative to wellbeing [53, 57, 73]; this paper reveals that the hostel environment even with harm minimisation employed can be perceived as physically and psychologically unsafe [61, 70].

Although harm reduction policies have been implemented around the globe since the 1990s, this review demonstrates that it is hard to lead a healthy lifestyle while living in a hostel [54, 68] and drug and alcohol use were used to help manage the difficulties and distress arising from the residents lived experience [60, 68, 71]. Reports from charities like Shelter and Groundswell documented the relationship between poor housing and worsening physical and mental health [82] that homeless hostels are making people sick [83] and that the approaches taken fail to care for people with complex needs [84].

Positive findings in relation to living in a homeless hostel were limited to good links with agencies [44], more stability [76] and hope for residents [78]. It is notable, however, that the findings of this review predominantly identify the challenges of living in a homeless hostel which tended to be negative experiences. Many of the residents’ experiences of living in a homeless hostel will be impacted by and intricately woven with previous life events, maladaptive coping mechanisms, histories of vulnerability, previous experiences of homelessness and stigma, experiences of substance use and multiple other factors which can be hard to disentangle from their experiences of living in a hostel and the impact that this had on their health and wellbeing. These findings should not therefore be taken as a critique of committed homeless hostel staff, many of which provide excellent care to some of the most vulnerable members of our society. More research, which focuses on untangling previous experiences of homelessness from experiences of living in a homeless hostel, is therefore needed to understand the impact of homeless hostels on residents’ health and wellbeing.

What is also revealed from the scoping review is systems under pressure, with many homeless hostels that may not be fit for purpose impacting people’s experiences and negatively impacting their health and wellbeing. This is exacerbated by real challenges within this cohort of not just accessing care but accessing considerate and person-centred care. Homeless hostel residents experience feelings of being stigmatised both from the public and those in healthcare roles that are there to support them. Trauma is prevalent and resultant coping mechanisms such as alcohol and drug misuse can serve to further exacerbate poor health.

The results of this scoping review have some implications for future policy development in the design and delivery of homeless hostels. This should include processes to ensure cohesive multiprofessional care for residents of homeless hostels and attention to changing the hostel environment to enhance health and wellbeing.

It also draws into view the need for a deeper understanding of the experience of living in homeless hostels from the perspective of those who really know. Applying the research approach of hermeneutic phenomenology and other qualitative methods seeking depth to such an experience could result in a more nuanced comprehension of the experience. This could then inform responsive policy development and practical changes to the environment.

5.1. Limitations of This Study

Due to a paucity of data, it has not been possible to make any considerable comparisons between the experience of men and women, but there is a notable new wave of research addressing the lack of targeted evidence captured on women. Any comparisons based on race or ethnicity have also not been possible due to a lack of information. Several of the studies included both staff and residents, and it was not always possible to separate their voices. This could impact the richness of the disclosed lived experience.

With a scoping review on lived experience, there is an inevitable scarcity of quantitative studies. This can result in minimal objective measurements of health and wellbeing with the lack of studies based on epidemiological data meaning that it is difficult to quantify the issue which may have implications for being able to influence policy makers. Furthermore, the lack of statistical studies means that it is difficult to untangle issues such as correlation and causation. There are some identifiable limitations to this scoping review including the exclusion of literature in other languages. Homeless populations are in many ways a hidden population and transient in nature so longitudinal projects are particularly challenging and notably absent in the scoping review.

6. Conclusion

This scoping review explored the literature on residents lived experience of living in a homeless hostel and the impact on health and wellbeing. We believe that this is the first scoping review to focus on this issue. The findings disclose experiences of difficulty accessing care as well as experiencing stigma. Survival tactics were employed, and chaotic lifestyles were evident as responses to the challenges of living in the hostel environment. The hostel itself and the experience of homelessness were found to impact on health and wellbeing. In its totality, this review demonstrates a picture of disadvantage, discrimination and increased disease burden within the populations of homeless hostels and shows that there is work to do to achieve equilibrium between the residents and their environment [85]. More research into the actual experience of people living in homeless hostels is required. Explorations of how homeless hostels can be strengthened to improve health and wellbeing and reduce harm would be worthwhile.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Supporting Information

PRISMA extension checklist.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.