Communication as an Unequal Game: Insights Into Language Barriers and Missed Opportunities From the Perspectives of Nurses, Doctors, and Professional Interpreters

Abstract

Objective: In the context of serious illnesses, such as cancer, effective communication is vital. This study explores how registered nurses (RNs), medical doctors (MDs), and professional interpreters (PIs) experience communication in cancer care with patients who have limited proficiency in the dominant language.

Methods: A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach was employed using focus group interviews. A total of 23 informants participated and were divided into six groups: three groups of nurses, two groups of doctors, and one group of interpreters. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with Paul Ricoeur’s critical hermeneutics serving as the theoretical framework for analysis and interpretation.

Results: The overarching theme identified was Communication as an Unequal Game, with three subthemes: (1) Communicating on unequal terms, (2) Lack of agreed roles and shared rules, and (3) Missing opportunities as an invisible consequence. The findings reveal an experience across professions of being at a disadvantage from the start due to strict time constraints and lack of access to essential knowledge. Differing views on the roles of interpreters, including whether they should act as robots or engage as human beings, further complicate communication. Without clearly agreed-upon roles and shared rules, decisions about briefing or booking interpreters come to rely on individual perceptions, leading to inconsistent practices and communication inequalities among professional groups. The findings highlight the less visible consequences of language barriers in healthcare encounters, including lack of treatment options being presented to patients and the mental and physical withdrawal of nurses when no interpreters are available to facilitate verbal communication.

Conclusion: While it is necessary to embrace the inherent complexity of language-discordant communication, it is equally important to establish a more level and stable “playing field,” including targeted interprofessional collaboration. In the current unequal game of communication, language barriers not only impede effective communication but also make choices—and care—disappear.

1. Introduction

The Hippocratic ideal of “cure sometimes, treat often, and comfort always” remains a cornerstone of modern healthcare [1], underscoring that medical care involves more than just treatment. Since ancient Greece, the principles have evolved to emphasize patient needs and preferences through concepts like, “patient-centeredness,” “patient engagement,” and “shared decision-making” [2–4]. In other words, today’s healthcare approach prioritizes putting patients first by actively involving them in their own care and treatment decisions. This is highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) initiatives such as “patients for patient safety,” with one of its key goals being to “bring the voices of patients and people to the forefront of healthcare” [5].

While the Hippocratic ideal provides the ethical framework for medical care, communication is the key tool that enables its practical application in everyday healthcare practice. In this regard, the literature stresses the many positive outcomes of effective communication [6, 7]. If tailored to patients’ health literacy [8], it helps patients understand their conditions and treatment options, supports shared decision-making [9], and is crucial for building trusting relationships between patients and healthcare providers [10]. In sum, effective communication enables healthcare providers to address and support patients’ physical, emotional, and psychological needs, as well as those of their closest support systems, i.e., family caregivers, crucial in the context of critical illness such as cancer [11].

As the world becomes increasingly diverse, however, so does the linguistic landscape of healthcare [12]. Recent studies demonstrate how first-language discordance between patients and healthcare providers significantly challenge communication during cancer care [13, 14] and threaten patients’ psychological well-being [15, 16], ultimately compromising patient safety. Despite the recognized importance of effective communication and the identification of language barriers as the primary challenge [17, 18], there is limited insight into how these barriers affect the experiences of professionals directly involved in providing care to patients with cancer and limited dominant language proficiency [17]. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of studies that simultaneously include the perspectives of nurses, doctors, and professional interpreters. Since each of these professional groups plays a unique role in communication [19–21], their combined perspectives are essential for improving the overall quality of healthcare.

1.1. Aim

The aim of this study was to explore how language barriers impact communication in cancer care from the perspectives of nurses, doctors, and professional interpreters, focusing on their experiences and challenges.

2. Method

To elicit and understand participants’ lived experiences, the study employed a phenomenological-hermeneutic approach [22] and focus group interviews for collecting data [23]. Due to its qualitative design, the study is reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [24].

2.1. Setting and Participants

This study constitutes the third and final phase of a larger ethnographic study examining communication during language-discordant encounters between non-Danish-speaking patients and oncology clinicians in two outpatient cancer clinics at two Danish public hospitals. According to Danish regulations, patients who do not speak or understand Danish are entitled to interpreter assistance, and the doctor is responsible for assessing whether an interpreter is needed. For patients who have been in the country for more than 3 years, an interpreter fee generally applies, unless specific exceptions are met.

In total, 23 informants participated in this final phase: 13 registered nurses (RNs) and seven medical doctors (MDs) from different diagnosis-specific teams and three professional interpreters from the regional interpreter center. In the following, these informants are referred to as “nurses,” “doctors,” and “interpreters,” respectively. This does not apply in parentheses referencing quotes, where their abbreviated formal titles (RN, MD, or PI) are used. All three interpreters, each representing a different language, as well as 18 of the nurses and doctors, had also participated in the first phase of the larger ethnographic study. The first phase involved participant observation in the clinical setting to investigate the communicative processes during language-discordant encounters [14]. During that phase, the interpreters had been observed collaborating with the nurses and doctors via video and/or telephone, the most commonly used interpreting formats in both outpatient clinics.

2.2. Data Collection and Methodological Considerations

Six focus group interviews were conducted by the first author (LB) during August and September 2023. To minimize the risk of power dynamics affecting participants’ willingness to speak openly [23], the groups consisted of three groups of nurses and two groups of doctors, organized across the different diagnosis-specific teams, and one group of interpreters. For an overview, see Table 1. To protect participants’ anonymity, only general information has been included.

| Focus group | Participants | Format | Recording duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 nurses | Physical (at hospital X) | 51 |

| 2 | 4 doctors | Physical (at hospital X) | 43 |

| 3 | 5 nurses | Physical (at hospital X) | 50 |

| 4 | 4 nurses | Physical (at hospital Y) | 51 |

| 5 | 3 doctors | Physical (at hospital Y) | 55 |

| 6 | 3 interpreters | Online (teams) | 68 |

Staff members from the two hospitals facilitated contact with nurses and doctors and assisted in arranging the interviews, which were all conducted in the hospitals. The regional interpreter center helped identify the interpreters who had participated in the first phase of the larger ethnographic study. Upon their oral consent, LB received their contact information and arranged an online focus group interview due to logistical challenges. Given its online format, this interview was video-recorded, whereas all five interviews with nurses and doctors were audio-recorded.

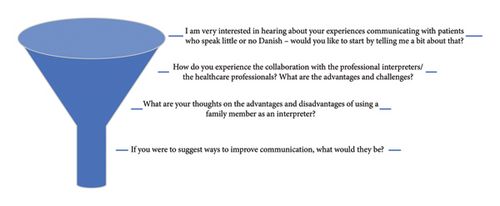

While focus groups carry the risk that participants may be reluctant to share their thoughts, the method was chosen because synergetic effects often emerge, inspiring participants and leading to new perspectives on the topic [25]. In this way, it is possible to generate a more nuanced dataset compared to individual interviews. Moreover, data from the first phase of the larger ethnographic study [14] were used to prepare and nuance the questions that guided the interviews. The interview guide had a traditional funnel format, allowing for open questions initially while ensuring that the overall aim is addressed [23]. Accordingly, as illustrated in Figure 1, opening questions were less structured, addressing participants’ general experiences related to language-discordant communication. The more structured questions in the middle of interviews revolved around more specific aspects that had been observed during the first phase of the larger ethnographic study.

2.3. Researcher Positioning

With a background in English and Nordic languages and literature, including several years of teaching language courses to non-native speakers, LB had practical experience in addressing language barriers. Within the field of healthcare, however, her experience was relatively limited, facilitating an open approach marked by humility and respect for the participants’ expertise within the field. In accordance with methodological recommendations [23], before initiating the interviews, LB explicitly stated that all experiences are valuable and contribute meaningfully to the research. Consistent with this approach, LB emphasized that there are no right or wrong answers and stressed the intent to learn from participants.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (REG-22-30001) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. According to Danish law, no further ethical approval was required due to the study design. This was confirmed by the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics for Southern Denmark that forwarded the decision (journal no.: 20202000-236). Written informed consent was obtained before interviews.

2.5. Data Analysis and Interpretation

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and Paul Ricoeur’s critical hermeneutics provided the theoretical framework for analysis and interpretation. Specifically, the analysis followed Ricoeur’s theory of interpretation [26], involving three phases. In the initial phase, naïve reading, an immediate understanding of the text as a whole, was achieved while the second phase, structural analysis, offered a more objective understanding. During this second phase, transcripts were divided into units of meaning (quotes), to which units of significance (explanations) were added, and themes were identified. Rather than being a linear process, this structural analysis was dialectical, with both main themes and subthemes being revisited and revised as the analysis progressed. This phase not only provided an important “trail of evidence” [27] but also served as a crucial mediation between the naïve reading and the final phase: critical interpretation.

In the critical interpretation phase, the text was reassembled to achieve a comprehensive and new understanding. Important in this context, Ricoeur incorporates into his thinking Habermas’ critique of ideology [28], and aspects of critical discourse analysis [29, 30] have been integrated to address power dynamics revealed in the interviews. In accordance with Ricoeur’s eclectic approach to interpretation [26] and the argument that the depth of discourse analysis should align with the research aims and context, a full discourse analysis was deemed unnecessary. Finally, the structural analysis was continuously discussed with the last author (DN), while selection of literature used in the discussion was conducted collaboratively by all authors based on the study findings.

3. Results

One overarching theme was identified, Communication as an Unequal Game, which was further divided into three subthemes: (1) Communicating on unequal terms; (2) Lack of agreed roles and shared rules; and (3) Missing opportunities as an invisible consequence.

To ensure consistency and transparency, the following presentation includes short quotes integrated into the main text and longer quotes presented as indented blockquotes (e.g., excerpts from participants’ discussions). Additionally, to maintain rigor, further units of meaning used to identify each of the three subthemes are presented in three separate tables, which will be elaborated upon in the subsequent section under their respective subthemes. Finally, the following analysis addresses both interpreter-mediated conversations and patient encounters without professional interpreters. As the focus is on cross-cutting themes rather than specific languages, references to countries or languages have been blinded in alignment with the anonymization of interpreters’ languages in the study.

3.1. Communication as an Unequal Game

During the interviews, it became clear that language-discordant communication was experienced as fundamentally difficult. This was underlined with negative adjectives such as “difficult” and “hard,” not only used across all three professional groups but also repeated throughout interviews. Both local (linguistic) challenges and structural challenges (technical and temporal) seemed to significantly affect participants’ experiences of communication. In this regard, the use of figurative language, including game-related terminology, highlighted a shared perception of communication as a game played out on unequal terms.

3.1.1. Communicating on Unequal Terms

Though a few positive aspects of interpreter-mediated communication were highlighted among nurses and doctors, such as being provided more reflection time between speaking turns (Group 5, MD2) and being forced to keep communication more concise (Group 2, MD2), nurses and doctors seemed to share the experience of incomplete, broken communication. As a doctor puts it: “Communication is one of our tools, but it gets completely disrupted when it goes through an interpreter, so it’s very difficult to have a communication that you’re happy with” (Group 2, MD1).

-

Nurse 5: What you normally say becomes brief, and it turns into text message language, right, “The-treatment-is-going-well”

-

Nurse 4: Yes

-

Nurse 5 (with a robotic voice): “Are-you-rea-dy-for-more-treat-ment? Do-you-have-any-aller-gies?”

As demonstrated, compared to the communication with Danish-speaking patients, nurses describe interpreter-mediated communication as not only becoming more simplified but almost mechanical, like a robot. In contrast, interpreters describe it as “optimal (…) when the clinician speaks in shorter (completed) units” (PI1) and that a (linguistic) “symbiosis” can even develop between the clinician and interpreter. When both parties are trained in interpreter-mediated conversations, it can almost come to resemble “simultaneous interpreting” (PI1); a potential also indicated by a doctor, who recalled a collaboration with a blind patient and a sign-language interpreter where the conversation flowed more naturally, similar to language-concordant communication.

-

Doctor 4: Perhaps the interpreter is not ready, we also experience that

-

Doctor 3: Or we’re not ready

-

Doctor 4: Then the equipment doesn’t work

-

Doctor 3: Right, and you can’t make the call

-

Doctor 4: And you’re surprised that it involves an interpreter, then you have to first find the equipment

-

Doctor 3: Right

-

Doctor 4: Yeah, you’re lagging behind from the beginning

-

Doctor 3 (Group 2): There’s a bit of panic before starting because you have to be ready for when the interpreter joins the call, you have to make sure that we have enough time, you know. So, sometimes you’re already a bit stressed out before the conversation begins, and then you need to make sure the equipment is working.

-

Nurse 4 (Group 1): And then you might be a bit behind, and you’re running around getting that screen. And then you’re ready, but the doctors aren’t because they’re involved in something else.

-

Interpreter 3 (Group 6): I’m waiting for an hour of interpretation, and then they call me after half an hour or 45 min and actually needed a full hour. This also affects my working conditions because I stress about whether we’ll get through everything, whether I’ll manage to say everything that needs to be said, or if I’ll have to say, “You know what, that’s it, I have to end the call.”

In addition to constantly running behind because “appointments are never on time” as described by a nurse (Group 3, RN4), all three professional groups described a shared experience of communicating within a context characterized by a lack of knowledge. This is illustrated in Table 2.

| Example 1 (Group 2) | Doctor 2: And sometimes, I really worry whether what I’m saying is being translated correctly. It’s something that really concerns me. |

|---|---|

| Doctor 4: Yeah, there’s no way to know. | |

| Doctor 1: There’s no way to know, and it actually bothers me a lot when I’m talking with those patients because you know, it’s harder to read their facial expressions, I think. | |

| Doctor 4: Exactly. | |

| Doctor 1: Compared to when you’re speaking Danish. | |

| Doctor 4: Yeah, because when you say something, you expect some kind of game to be played, and when it’s going through another person, you lose that sense completely. | |

| Doctor 1: Right, you don’t get any sense of their reaction or how they’re understanding what you’re saying. I find it really difficult. | |

| Doctor 4: I completely agree. | |

| Example 2 (Group 3) | Nurse 1: If they don’t speak English, it’s sign language to the best of your ability. And facial expressions and a hand on the shoulder, if you feel you can afford it after observing. It becomes very fluttery, so you’re really left out (of the game) if they don’t understand anything, and otherwise some of them may understand a little Danish, but they can’t speak the language themselves, so speaking clearly and lip-reading a little, and in that way, all the other things (senses) come into play, but it’s really difficult. |

| Example 3 (Group 6) | Interpreter 3: If we’re dealing with a very rare form of cancer that you’ve almost never heard of then it’s also nice that it’s written (in the comments field) because then we can do a little research. It’s not that we become doctors that way, but we can do a little research in Danish, we can do some research in our own language and familiarize ourselves with things a little more that way. |

| Interpreter 1: I can only say yes to that. It’s incredibly important and crucial, because of course they (the patients) feel… I also feel (blind) when I go into an interpretation completely blind, without any idea of what it might be. |

As the first two examples show, doctors and nurses described feeling uncertain when having no idea what is communicated between patients and interpreters, and in more cases, the terms of communication were even juxtaposed to those of patients with physical disabilities, including hearing or visual impairments. As one of the doctors in Example 1 puts it, she expects some kind of collaborative “game” but describes how the (nonverbal) knowledge she normally senses during a conversation gets lost in the process of interpretation. In continuation of this, decoding patients’ body language, including facial expressions, was described as particularly difficult, and in more cases, this was partly ascribed to different cultural norms being at play.

Whereas both nurses and doctors emphasized the need for more cultural knowledge, body language was assigned a pivotal role, particularly when communicating with patients in the absence of interpreters. As exemplified in Example 2, more nurses described how being unable to communicate verbally with patients during treatment sessions makes other senses “come into play” (the visual). Notably, however, as highlighted in the example, such difficult terms of communication can lead to feelings of being completely “left out” (of the game). The interpreters described a similar experience of groping in the dark during communication, however, as a consequence of not being briefed about patients beforehand. This is illustrated in Example 3 where the terms of communication are directly compared to being blind.

In fact, across all three professional groups, having prior knowledge about the patient was emphasized as highly significant. Thus, the consequences of racing against time were underscored when the discussion turned to the use of family members as interpreters. While it was noted that, in principle, family members ought not to interpret, it was described how involving them is sometimes considered more effective, as they already know the patient’s history (Group 5, MD3). Along the same lines of not having to spend time on briefing a professional interpreter, another nurse described how not utilizing the full interpreting time allotted can sometimes be the easier choice. As she said: “Then you can just win an extra 15 min there” (Group 4, RN1).

3.1.2. Lack of Agreed Roles and Shared Rules

While all three professional groups agreed that organizational frameworks challenge an already fundamentally difficult communication process, several participants emphasized that successful communication also relies on each other’s collaborative communication skills. When discussions specifically focused on video interpreting, however, differing views on the roles of interpreters appeared as an additional challenge.

While some doctors and nurses described an increased sense of distance with video interpreting, making it even harder to decode body language, others preferred the format for its efficiency. Interpreters themselves also described video interpreting as effective but, more importantly, emphasized that the physical distance from patients becomes crucial when conveying life-changing messages:

I’m a communicative channel. Through me, just like broadband, all kinds of messages reach the patient. Sometimes, these are life-or-death messages. We also talk about death. Sometimes it’s through my mouth […] that the message reaches the patient: “You don’t have much time left on earth, so do you want to discuss your last wishes, or what you need to arrange?” That distance… it’s tough […] even though I’m not in the same room as the patient. We can’t avoid saying that we’re affected, that I’m affected. […] It would be a lie to say that I’m not affected by a really tough interpretation, just as I’m affected by a fantastic birth where everything went well, and I see two young parents holding their little baby. I… feel with them. That’s how it is. We’re there. Or are those all my feelings? I don’t know. But the advantage [for me] is that I’m not in that room (PI1).

As the quote underlines, the interpreters describe themselves as both communicative channels and individuals with feelings, and the description highlights the often contrasting and emotional nature of interpreters’ tasks. However, as Table 3 below reveals, there is disagreement about this role. Specifically, the interviews reveal a debate over whether interpreters should act as robotic translators or engage as human beings.

| Example 1 (Group 6) | Interpreter 1: Interpretation is much more than just translating a word, a concept, or a sentence. There’s incredibly much more at stake with interpreters; we interpret behavior, we interpret emotions, we interpret history, we interpret the situation, and it’s very important that we always interpret in a specific situation. This should never be forgotten by either the practitioner, the patient, or the interpreter. So I think it’s incredibly important with communication. […] |

|---|---|

| Interpreter 3: It’s not just about translating. It’s also about how you translate, like maybe with a calming voice, providing a sense of reassurance in the way you interpret […]. It’s important because when someone is in a frustrating situation, if you were just a robotic translator, they would feel even more insecure. So, it’s very important in the work we do. We also have emotions, and we can empathize, and it influences how we interpret, and that’s also crucial because it provides a sense of security. And it can be really difficult for some people to express themselves in a foreign language, especially when it involves illness. It’s comforting for them to do it in their mother tongue, and that’s where we can help with translation. | |

| Interpreter 2: Yes, I completely agree with [name] and [name]’s views. I would also add, or put it differently, that in principle, we usually try to translate word for word, but we always discuss and consider whether it should be word for word or if we should also convey cultural aspects of the message. Because sometimes, when you interpret word for word, misunderstandings occur, or it happens that the practitioners can be quite strict in achieving their goals. So, if we translate it literally without incorporating some cultural translation or mediation, the patients might misunderstand and think the practitioner doesn’t care about their feelings. That’s why I always say… even though there are differing opinions, it’s something we constantly discuss because there are two different approaches. Some believe we should translate word for word, but I and some of my colleagues believe that we should also convey the cultural context. It’s not just about translating words. | |

| Interpreter 1: And that’s one of the points I’d like to add when we talk about language… we must never forget, and neither should the practitioners, that language is always tied to a specific culture. They cannot be separated. A person is born into a certain culture, and within that culture, they develop their language. They cannot be separated, they simply can’t. | |

| Example 2 (Group 2) | Doctor 4: I think I approach it a bit differently. I think I focus on keeping the interpreter as much in the background as possible, only using their words, and then I try to keep my sentences short and have them translate continuously. And I find it easier when they’re on a screen rather than physically in the room because then they don’t interfere as much. I think it’s easier to use them purely for the words. Yes, so they become a tool and not a… this sounds wrong, but not a person. |

| Doctor 3: Not a person… | |

| Doctor 4: No, they become my words. | |

| Doctor 3: Yes, exactly, and that’s probably where I’m different. I mean, I try to incorporate the interpreter’s human skills as well because they need to understand the mood. I mean, it’s probably, actually, because I’m trying that thing called care by sort of letting the interpreter know, ‘where am I,’ so they’re aware that this is a sensitive conversation, or this is a | |

| Doctor 4 (interrupts): I don’t think that way at all. I wouldn’t use, I mean, I don’t use them for that at all. I try to be much more present, physically, or… yeah… | |

| Example 3 (Group 3) | Nurse 3: But I think they do a good job, those interpreters, they do. It can’t be easy, you know, because they sit there having to interpret, and we have to give a bad answer, ‘there’s no more treatment,’ and then the next, it’s a wart with a doctor. Just think about what those interpreters have to deal with. But we also had, weren’t you part of that discussion, [name], about how we should view the interpreter, where one of our doctors thought an interpreter was just a machine, not a person sitting behind the screen, which is how we nurses might think of it a bit, but an interpreter was just supposed to say what was said, end of story. And we nurses don’t think that at all. It’s a person who is part of the conversation, I think often, on some level. |

| Nurse 2: And it’s such an important link because it’s the interpreter who actually needs to get the patient to open up since the patient can’t understand what we’re saying. | |

| Nurse 5: But we’ve also experienced the other extreme, where the interpreter and the patient almost spent the first quarter of an hour just getting to know each other, and we were like… (knocks on the table as a hurry-up signal) |

As Example 1 shows, the interpreters perceive their role as encompassing not only language translation but also cultural mediation and providing patients’ safety. At the same time, they are aware that doctors and nurses may not always agree with this. This is illustrated by the recall of encounters with healthcare professionals who, “in order to reach their goals,” expect interpreters to perform robotic translations without interfering. Important in this context, the interpreters both emphasized and acknowledged the responsibility of nurses and doctors to “control the conversation and set the framework” (PI2). Yet, at the same time, the interpreters described how they sometimes find themselves needing to “moderate the tone” when, for instance, doctors show visible signs of “being pressed for time” (PI1) or having to interfere to ensure accurate understanding. Importantly, interfering can be perceived as running a risk: “If I feel that these two people are talking completely past each other […] then I ask very politely, of course, to interfere a little bit […]. The most important thing is that everything ends well, even if I might get a knock on the head” (PI1). Nonetheless, this willingness to interfere seemed driven by the interpreters’ goal of ensuring that “the patient receives the best possible quality of care” (PI1).

While some doctors described the interpreter as a “tool” or “machine” that should not interfere, this view was not shared by all doctors as also reflected in the dialog between two doctors in Example 2. Similarly, more doctors acknowledged the complexity of interpreters’ tasks. Nevertheless, Example 2 demonstrates how not only time pressure but also differing perceptions of interpreters’ roles directly impact on whether or not interpreters are briefed before a conversation. In fact, differing perceptions prove to have a decisive impact on whether an interpreter is present at all as underscored by a nurse who recounted a discussion with a doctor during a patient consultation: “The doctor said, ‘We don’t need an interpreter when she’s just coming in for treatment; it only takes 15 min’” (Group 3, RN1).

In continuation of this, Example 3 in Table 3 illustrates how many nurses acknowledge interpreters’ often contrasting and emotional tasks, ranging from discussing a foot wart to delivering a terminal diagnosis. Put differently, the example shows recognition of interpreters as both human beings and crucial communicative and relational links between patients and health professionals. Additionally, the example underlines the differing views on this role, highlighted when the nurse recalls a doctor who insisted that interpreters should be considered “machines.” Meanwhile, the recollection of a patient and interpreter nearly spending the first quarter of an hour getting to know each other not only indicates a debate about whether interpreters should build relationships with patients before medical conversations but also highlights a complex relationship between time constraints and the need to prioritize.

To further illustrate the contrasting perspectives, the following question posed by a nurse in another group revealed an underlying understanding of direct translation being integral to the interpreter’s professional responsibilities: “The interpreter – what should she lean on? culture or her professional duties? I think that must be quite difficult, actually” (Group 4, RN4). In other words, while the nurse acknowledges interpreters’ often complex tasks, the quote clearly contrasts with how interpreters view their own role as outlined in the first example in Table 3; a role based on the belief that language and culture “cannot be separated.”

Aside from revealing a lack of agreement on the roles of interpreters, the interviews also revealed a lack of fundamental shared rules as a basis for communication. To illustrate, a nurse from one team described a culture where “there is an interpreter for everything” (Group 4, RN2), while a nurse from another team wondered how a culture had developed where “it should only be when it’s necessary” (Group 1, RN1). In accordance with this, some doctors did not consider time or cost when using interpreters, while another doctor wished it were “more legitimate to spend the time on interpreting” (Group 2, MD1), indicating more underlying disagreements. Consequently, both doctors and nurses explicitly requested clearer rules, while nurses across all three groups agreed that they could be “better at making agendas with doctors” (Group 1, RN2). To achieve what appeared to be the nurses’ goal of “getting all the way around the patient” (Group 1, RN2), a nurse suggested that they should “put all cards on the table” at the start of interpreter-mediated conversations (Group 1, RN4). According to nurses, this approach would facilitate better collaboration based on aligned expectations, ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to communicate effectively and that all parties’ communicative needs are met, including the patient’s.

The interpreters similarly formulated a suggestion for improving communication within the context of playing a game when they extended a direct invitation to consider interpreters as colleagues rather than competitors: “You’re not an opponent; you’re not a competitor. You’re a colleague” (PI1), subject to the same confidentiality obligation.

3.1.3. Missing Opportunities as an Invisible Consequence

While interpreters highlighted the importance of adaptability in communication to meet various situations and needs, their discussions also revealed differing opportunities for interprofessional collaboration. While one interpreter (PI2) described good options for extending interpreting time when needed, another interpreter described a contrasting experience, explaining that this often depends on the linguistic demand for the interpreting language, frequently leaving interpreters unable to extend: “In my situation (interpreting in a language with fewer available interpreters), we’re quite vulnerable when it comes to time. If I have another appointment right after, there’s not really much to be done […]. So yes, there is an opportunity for extensions if someone is available” (PI3).

-

Doctor 2: And you could say that the whole clinical trial option…

-

Doctor 3: Yes

-

Doctor 2: … they don’t get that either

-

Doctor 4: They don’t get those

-

Doctor 2: Because the protocols aren’t translated… into their language… so they can’t read the Danish participant information… so if it’s a good trial option… they don’t get that offer

-

Doctor 2: Yes, in that way, they’re cut off from certain things

-

Doctor 4: Right

-

Moderator: Just out of curiosity, what kind of trial options would these be?

-

Doctor 2: For example, when standard options are exhausted and the patient is still in good general condition, we have various trial offers… but they don’t get those, and these are additional treatment options

-

Doctor 4: Yes, and options that we believe are better

-

Doctor 2: Yes, we run these trials because we believe they’re better, absolutely

Furthermore, when discussing shared decision-making, the first example in Table 4 below reveals an expectation of cultural norms potentially being at play again but, more importantly, the example demonstrates how language barriers literally make choices disappear during decision-making processes.

| Example 1 (Group 2) | Doctor 1: I still think it’s harder to do shared decision-making with those patients because you’re still missing some nuances, and you’re also missing this cultural background that most Danes have, you know. I think you can inform them better about shared decision-making than I can with someone who doesn’t speak my language. |

|---|---|

| Doctor 4: It’s probably also because they’re not used to us asking them [for their input] because they’re not familiar with it. | |

| Doctor 4: It’s not something they know. It’s not something they understand. | |

| Doctor 1: Many are really surprised, and that’s what I meant, but I might have explained it a bit wrong. | |

| Doctor 2: Well, I think it would take a lot for me to use shared decision-making in a conversation through an interpreter. I mean, maybe I’m a bit biased, but – of course, if the person is highly educated, then maybe I could – but often, the ones we see don’t have much education, and I would probably tailor my conversation more simply… frame it as an offer and not a choice. I don’t think I’d ever present more options than just, you can choose to do something, or you can choose not to. I think that’s what I would probably do. I definitely keep my communication much simpler. I do. | |

| Doctor 3: I also think the language barrier is a gigantic barrier to practicing shared decision-making, I just wanted to say that. | |

| Doctor 4: But it could also be interesting to look at whether it’s actually an advantage that we speak slower when it’s a patient who speaks a different language, and maybe there’s more attention to the non-verbal [cues], and we don’t give all kinds of unnecessary information. Yeah, I also think, can’t there be any advantages to it? | |

| Doctor 1: Can there be any advantages to it… | |

| Doctor 4: Sometimes I think we leave out some information. They get the information that is need-to-know | |

| Doctor 1: Yeah… as we believe [is need-to-know] | |

| Doctor 4: As we believe, absolutely right, good point. | |

| Example 2 (Group 4) | Nurse 2: I think if I could make a wish for how things should be ideally, it would be for more time, so I could get through all the practical stuff but also take a moment to say, no matter where they’re from, “so, what was it that you did there?.” If they’ve fled from somewhere, or, “do you have family left behind?.” Because I really try to do that as much as I can with patients who speak Danish. Of course, they have a disease, but it’s the person who comes in with the disease. But with patients who have a language barrier, it tends to be more about the disease, and they just happen to come along with it. There’s not as much space to get to know the person behind it somehow. So, I wish there were more time allocated in the schedule because of the language barrier, since right now, they’re just booking based on how long the treatment takes, but the fact that the language barrier makes it take longer isn’t accounted for. |

| Nurse 3: That’s a huge issue, I think. | |

| Nurse 1: And also, they’ve got so much baggage with them – maybe they’re carrying real trauma, and if you start asking about it, like if there’s a child left behind in [their home country] or something, and they completely break down, then you have to make sure you have the time to provide the care they need. And sometimes that might hold us back a bit because we don’t really know what we’re getting into if we ask those questions, you know, like, she came alone with her daughter, what have they left behind in [their home country]? | |

| Nurse 4: We can’t really ask those questions if we can’t really pick them up afterward. | |

| Nurse 3: No, exactly. | |

| Nurse 4: Sometimes you can do more harm than good because we really want to help and do everything, but if we don’t have the right conditions and framework, then I think you have to be careful. | |

| Nurse 3: Yeah, and then you hold back, right? So, you don’t do it. | |

| Nurse 4: So, you end up not picking at that wound. | |

| Nurse 3: Yeah, exactly. But that just makes you think, in some way, that you could have done better, and you know you would’ve done that for a Danish family. |

As the final part of Example 1 demonstrates, the discussion between two doctors reaches a shared understanding that what health professionals consider “need-to-know” information may not always align with patients’ needs, potentially resulting in missing opportunities from the patient’s perspective. In continuation of this, language barriers not only make treatment options disappear. According to both doctors and nurses, language barriers make care disappear. While a doctor formulated how, “there is simply a lack of care being translated” (Group 2, MD3), a nurse bluntly concluded “They don’t get the same quality as the others [Danish-speaking patients]. They get their treatment” (Group 1, RN2).

Among nurses, being able to provide care was emphasized as highly significant, articulated by one nurse as follows: “Seeing the patient first is almost engraved in our DNA, and maybe that’s why it feels so incomplete when you have a foreign patient that you can’t communicate with properly, either due to time or other circumstances” (Group 4, RN2). As exemplified in Example 2 in Table 4, the nurses’ descriptions revealed a particular experience of having “no time for care” and no opportunity to prevent the disease from entering the hospital first, as described by one of the nurses. Example 2 particularly demonstrates how nurses refrain from asking certain questions because they feel unable to “pick up” the patients afterward.

Notably, as the example also demonstrates, nurses can be left with the feeling that they could have “done better.” However, in many cases, it seems that nurses are left without any actual opportunity to provide proper care—not due to strict time constraints, but because of no verbal communication being enabled at all. To exemplify, a nurse from another group described how being the one “who takes over in the treatment room” is not only “difficult” but also “horrible” when no interpreter follows (Group 3, RN5). The nurse describes how she consequently shuts down emotionally: “You’re the one who has to hand out tablets, and you’re the one who has to be sure they can react to side effects, and you’re the one who has to pick them up if they actually have something on their mind… and I just shut down because it’s too difficult” (Group 3, RN5). Thus, nurses’ experiences of responsibility, combined with a lack of real ability to act, ultimately affect how they interact with patients. Accordingly, a nurse not only highlighted the tangible consequences of feeling powerless, but how communication inequality can lead to both prejudiced thoughts like, “Why the hell can’t you just speak Danish” and burnout: “You actually get a bit burnt out” (Group 4, RN3).

In continuation of this, the interviews revealed that language barriers not only make choices—and care—disappear. They also make nurses literally disappear. As one nurse puts it: “When the interpreter signs off, that’s it. And then you do that thing where you sort of disappear” (Group 3, RN1). Another nurse nuanced this perspective when she elaborated on what happens when communication becomes so difficult that the only choice, she feels she has left, is not to be there. In other words, the choice is not to participate in the game at all.

But the discrimination just becomes so obvious. I’ve caught myself, when the program says there was an interpreter and everything is fine, that I set up the treatment and then quietly dribble on, because I simply don’t know what to do with myself. You know, if there’s no opening, if you’ve never seen the patient before and know nothing about them, then I’m not there. Well, I’m there to set up the treatment, I’m there to ensure, “okay, okay?” and then I’m gone. If it were a Danish [patient], I might have asked 10 different things, or stayed longer, or checked in more often. But here, it’s almost like I think, “Shit, do I really need to go in there?” because they look at me… they… they just sit there, getting something in their arm that they might know nothing about, and I avoid… that’s what happens when there’s no communication at all. It’s really difficult (Group 3, RN4).

4. Discussion

Examining the combined perspectives of how language barriers impact communication revealed a shared perception of communication not only being fundamentally difficult but also unequal. Communication occurs on unequal terms, where participants face disadvantages from the start due to strict time constraints and lack of access to essential knowledge. Differing views on the roles of interpreters, including whether they should act as robots or engage as human beings, further complicate communication. Without clearly agreed-upon roles and shared rules (i.e., guidelines), in more cases, decisions about briefing or booking interpreters come to rely on individual perceptions of what is most important in the patient encounter. This results in inconsistent practices and communication inequalities among professional groups. Notably, our findings highlight the less visible consequences of playing this unequal game, including lack of treatment options being presented to patients and the mental and physical withdrawal of nurses when no interpreters are available to facilitate verbal communication.

The metaphorical framing of communication as an unequal game resembles what has previously been termed a “wicked game.” The concept, originally developed in the context of urban planning [31] and later applied to health and social care settings [32], describes a situation with no fixed rules, constantly changing players, and a complex and variable playing field. The implications for practice are clear, being that no one is capable of mastering the game [32]. Our findings reveal how a similar complex of problems is faced by all three professional groups who compare the communicative situation with that of patients with disabilities [33]. Our findings demonstrate how nurses, doctors, and professional interpreters alike feel communicatively impaired, missing crucial insights from nonverbal cues, patients’ cultural backgrounds, and medical histories—factors that the literature has already identified as essential for providing high-quality care [34].

In addition, our findings reveal that underlying power structures come to further shape the patient encounter, impacting the ability of individual professionals to communicate effectively with patients. In accordance with the literature [35], for some doctors in our study, the primary goal of communication seems to ensure accurate medical treatment. Consistent with the literature as well [36, 37], for other doctors, and nurses in particular, providing (linguistic) care, including listening to patients’ stories [38], seems equally important. Notably, this tension between treatment and care creates a paradoxical role for interpreters, who are expected to function as both human beings and translation machines, and who feel obligated to employ strategies beyond their professional assignments [39] in order to navigate ethical concerns.

Supported by other studies [17, 40, 41], the conflicting expectations contribute to inconsistent use of interpreters, increasing communication inequality. Yet, our findings suggest that the communicative challenges faced in our study extend beyond organizational frameworks and lack of agreed-upon roles and shared rules; they point to a more fundamental challenge: the absence of a clearly articulated shared goal for communication. Based on our findings, we argue that this lack negatively affects collaboration between professional groups and patients, limiting both patients’ and professionals’ opportunities to engage effectively in communication. In this regard, our findings show how treatment options concretely disappear during decision-making processes when healthcare professionals find communication too complex or feel ethically obligated to protect patients, as illustrated by the example of a doctor withholding treatment due to concerns about patients handling adverse effects.

Additionally, our findings reveal the loss of valuable communication with nurses. Our study specifically highlights a clash between nurses’ values and ethical responsibilities, on the one hand, and their actual opportunities to act in accordance with ethical recommendations and clinical guidelines, on the other hand. This clash is particularly evident in their role of “ensuring good judgment in clinical communication” [11]. Importantly, our study concretely demonstrates how a structural problem is internalized by healthcare professionals, leading them to change their behavior when they feel they lack opportunities for providing (linguistic) care. In accordance with existing literature, this internalization can contribute to what has been termed “shitty nursing” [42]. Our study specifically highlights how the inability to communicate effectively with patients results in dramatically reduced care quality. This is supported by numerous studies that have identified factors contributing to both coarsening [43] and burnout [44, 45] among staff, including compassion fatigue [46] and feelings of powerlessness [47].

Returning to the concept of a “wicked game,” the main difference compared to our overall finding of communication as an unequal game is the endpoint: whereas the wicked game never ends, from the perspective of healthcare professionals, our findings suggest communication being more or less “game over” in the absence of interpreters, leading to serious implications for patient care. In this regard, our study underscores the need to promote a healthcare system that supports professionals not only in becoming the best versions of themselves [43] but also in the context of a game, the best possible team players.

Thus, while our study primarily highlights challenges, it also points to possible solutions. Echoing Lundström et al.’s emphasis on creating “a collaborative playing field” [31], our study underscores the urgent need for a collaborative communication framework [48] with clearly agreed-upon roles and shared rules (i.e., guidelines) as a basis for communication. Achieving this requires not only targeted communication training but also a shared and clearly articulated goal; historically framed as, “cure sometimes, treat often, comfort always” as introduced at the beginning of this article. In a more modern version: provide the highest quality care. In the collaborative effort to achieve this goal, professional interpreters should not only be viewed as colleagues but also be recognized as the most experienced players, holding the key (or cards) to vital linguistic and cultural information [34, 49–51].

Drawing from our findings, we advocate for changes that specifically address the moral distress experienced by all professional groups. We propose the development of policies, protocols, and practices that integrate professional interpreters equally into both medical and emotional caregiving, thereby promoting effective collaboration. These changes could significantly improve the well-being of professionals, ultimately enhancing the quality of care experienced by patients.

While there is no simple solution to a so-called “wicked” [32, 52] or “wild problem” [43], part of the solution to the challenges highlighted in our study may be relatively straightforward: From an ethical perspective, respecting language rights [53] means that patients should always have access to the best possible treatment and be able to contact health professionals. In practice, this includes making medical protocols and leaflets available in languages patients understand [12], along with providing contact information. Meanwhile, mastering effective communication, much like completing complex team games, requires targeted training that takes into account individual patients’ health literacy [8] and respects cultural differences [36]. In sum, it takes a system that encourages patients to speak [5, 38] rather than staying silent.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

The participation of only three interpreters means that additional voices could have provided a more nuanced perspective. At its core, however, the combined perspectives of nurses, doctors, and interpreters provide valuable insights into the complexities of language-discordant communication; perspectives that stress the need for targeted interprofessional collaboration to address ethical issues such as epistemic injustice [12], that is, the unfairness that arises when certain groups are silenced or excluded from the communication process. Our study is conducted within a Danish healthcare context, which may limit the direct applicability of the findings to other settings. However, our primary focus is on language. While culture undoubtedly plays a significant role in healthcare interactions, language is fundamental—without a shared language, addressing cultural nuances becomes challenging. Thus, the insights from our study extend beyond the Danish context as language barriers represent a universal challenge in healthcare encounters.

5. Conclusion

Our results reveal that the current system’s structure does not support a patient-centered approach where language is tailored to meet the communicative needs of individual patients. While embracing the reality that language-discordant communication is complex by nature is necessary, on an organizational level, establishing a more level and stable “playing field” that allows professionals to engage not just with the patient but with the person is vital. Given that language, culture, and identity are inseparable components of a person, adopting a “language-first” approach could be a crucial step toward providing the highest quality care for all patients, regardless of their cultural and linguistic background. In the current unequal game of communication, language barriers not only impede effective communication. Language barriers make choices—and care—disappear.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark; Odense University Hospital, Denmark, under grant A4988; and the Danish Foundation, Østifterne, under grant 2021-0226.

Acknowledgments

We also want to thank gatekeepers in the Department of Oncology at Vejle Hospital and Odense University Hospital and from the regional interpreter center, Tolkecenter Syddanmark. Finally, we warmly thank the participants, who with both honesty and expertise help pave the way to the patients first.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

In compliance with participants’ written consent, no full dataset is available.