Comparative Analysis of Chemotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis, Nutritional Status, and Depression in Patients With Acute Leukemia

Abstract

Background: Chemotherapy, a fundamental treatment modality for acute leukemia, is linked to significant adverse effects such as oral mucositis, nutritional decline, and depression, all of which markedly impact patient outcomes.

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the progression of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis and its impact on nutritional status and depression in patients with acute leukemia.

Methods: In this prospective descriptive study, 123 patients aged 19–70 years diagnosed with acute leukemia were recruited from a tertiary hospital through convenience sampling. These patients were scheduled for remission-induction, consolidation, or reinduction chemotherapy. Initially, 140 patients were enrolled, with 123 participants included in the final analysis after accounting for incomplete responses and dropouts. Oral mucositis, nutritional status, and depression were assessed using validated scales, with follow-up evaluations conducted 10 days post-chemotherapy. Oral mucositis was assessed using the WHO Mucositis Grading Scale, symptom experiences were measured with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, nutritional status was evaluated with the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), and depression was assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). Statistical analyses included paired t-tests, ANOVA, and multiple regression.

Results: Compared to baseline, all the variables evaluated—oral mucositis, symptoms experiences, nutritional status, and depression—were significantly worsened on day 10 after chemotherapy. Regression analysis identified muscle weakness and skin problems as significant factors of depression. Additionally, patients receiving remission-induction therapy presented significantly worse depression than those receiving consolidation therapy.

Conclusion: This study highlighted the rapid deterioration of symptoms after chemotherapy in patients with acute leukemia. This underscores the need for a multidisciplinary approach that emphasizes nutritional support, emotional support, and evidence-based nursing interventions tailored to specific groups of symptoms. Future research should explore the educational interventions delivered during initial hospitalization and their effectiveness, particularly in patients receiving remission-induction therapy.

1. Introduction

Acute leukemia is a type of hematologic malignancy characterized by the disruption of normal hematopoiesis, leading to the impaired differentiation or abnormal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells. Without treatment, it progresses rapidly, resulting in fatal outcomes within 2–3 months due to its aggressive nature [1]. Chemotherapy remains the primary treatment but is often associated with severe side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and dysphagia, which impair nutritional intake and digestion, potentially leading to cachexia [2, 3].

One of the most common and debilitating side effects of chemotherapy is oral mucositis, which typically manifests within 3–7 days following treatment initiation and peaks around 10 days after treatment [4, 5]. This condition is characterized by erythema, edema, and ulceration of the oral mucosa and serves as a key indicator of chemotherapy toxicity. Patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy often experience nutritional deficiencies and electrolyte imbalances due to oral mucositis, which increases the risk of secondary systemic infections and complicates their treatment [6–8]. Oral mucositis not only causes significant physical discomfort but also negatively impacts patients’ functional capacity, emotional well-being, and quality of life. The associated symptoms can delay treatment, prolong hospitalization, and contribute to psychological issues, such as depression and anxiety [7, 9]. Moreover, chemotherapy’s systemic toxicity can result in gastrointestinal disturbances, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, and further psychological distress, making comprehensive nursing care crucial [10, 11].

Neutropenia, which typically occurs 1–2 weeks after chemotherapy, increases infection risk, leading to dietary restrictions that exclude raw fruits, vegetables, and undercooked animal products [12]. However, these restrictions often reduce patients’ nutritional intake, negatively affecting their nutritional status and quality of life [13]. Several studies have linked poor dietary intake with increased depression, and there is epidemiological evidence suggesting that antioxidants in fruits and vegetables have protective effects against depression [14, 15].

During periods of neutropenia, patients are often placed in isolation to prevent infections, which can exacerbate emotional distress, including anxiety, depression, and feelings of helplessness [16]. Previous research has demonstrated a correlation between poor nutritional status and elevated depression scores in cancer patients, highlighting the importance of addressing both physical and emotional aspects of care [17].

Despite extensive research on chemotherapy’s adverse effects, there is limited understanding of how oral mucositis, nutritional status, and depression interrelate in patients with acute leukemia. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the changes in the severity of oral mucositis, nutritional status, and depression in patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This descriptive and comparative study investigated differences in oral mucositis, symptoms experienced, nutritional status, and depression before and after chemotherapy in patients with acute leukemia.

2.2. Participants

Participants were patients diagnosed with acute leukemia who were admitted to an isolation unit for hematologic malignancy and scheduled for remission-induction, consolidation, or reinduction therapy. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: aged 19–70 years, had no prior diagnosis of depression before being diagnosed with acute leukemia, were not currently taking any depression medication, could read and interpret Korean without communication difficulties, understood the purpose of the study, and consented to participate. The chemotherapy protocols used for each type of disease are presented in Appendix A1.

The minimum target sample size of 120 was determined using G-power 3.1 software based on a two-tailed paired t-test with a medium effect size of 0.25, significance level of 0.05, and power of 0.80. To account for potential dropout rates, a questionnaire was administered to 140 participants. After excluding six patients with incomplete responses and 11 who dropped out of the post-survey evaluation (three were discharged, six were transferred to the intensive care unit and two were deceased), 123 participants were finally included in this study.

2.3. Measures and Scales

2.3.1. Oral Mucositis

The World Health Organization (WHO) Mucositis Grading Scale was used to assess oral mucositis. This tool assesses four areas of mucositis: oral erythema, oral edema, ulceration, and dietary form [18]. The scale comprises five grades. Grade 0 indicates that there are no abnormalities in the oral cavity, and normal functioning (no oral mucositis). Grade 1 indicates the presence of oral erythema without a sore throat or ulceration. Grade 2 indicates the presence of erythema and ulcers, with the patient being able to ingest solid food. Grade 3 indicates the presence of pain, erythema, and ulceration, with the patient not being able to ingest solid food, but capable of consuming liquid food. Grade 4 indicates severe ulceration to prevent oral food intake, necessitating non-oral or enteral feeding. Grade 2 shows a clear manifestation of symptoms attributable to oral mucositis compared to Grade 1 and is of greater clinical importance. Therefore, the presence of oral mucositis is defined as Grade 2 or above [19]. To assess the correlation with nutritional status, grades 3 to 4, characterized by the inability to eat solid food, were considered severe; grades 1 to 2, indicating the ability to ingest solid food, were classified as moderate; and grade 0 was designated as normal.

2.3.2. Symptom Experiences

The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/myelodysplastic syndrome, a cancer module, was used to assess the symptoms experienced by patients with acute leukemia following chemotherapy [20, 21]. This tool comprises 13 items that assess various aspects, such as pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep, nausea, distress, shortness of breath, difficulty remembering, loss of appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, and numbness/tingling. In addition, it includes 17 items related to the severity of leukemia, encompassing four items that address the symptoms of acute leukemia (discomfort, diarrhea, muscle weakness, and skin problems) and six items that assess the impact of symptoms on daily life: general activity, mood, work, relationships with others, walking, and enjoyment of life. Patients mark the score on this scale based on the severity of symptoms experienced at their peak within the last 24 h. For severity items, scores range from 0, indicating the absence of symptoms, to 10, representing the most severe symptoms. For the items that interfere with daily life, the scores range from 0 (no impact on daily life) to 10 (complete disruption of daily life due to symptoms). The total score ranges from 0 to 230. In this study, Cronbach’s α for severity items was 0.87, while that of the interference items was 0.82.

2.3.3. Nutrition Status

Nutritional status was evaluated using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), a tool adapted for patients with cancer by FD Ottery [22] from the Subjective Global Assessment scale, originally developed by AS Detsky, J McLaughlin, JP Baker, N Johnston, S Whittaker, RA Mendelson, and KN Jeejeebhoy [23]. The PG-SGA comprises two components. The first is a patient-generated section, which is officially known as the PG-SGA short form and is completed by patients. It is designed to cover approximately 80%–90% of the scores. The second component, known as the professional component, was developed as worksheets to raise awareness about the often-overlooked causes of malnutrition in clinical settings, such as fever and corticosteroids. The five worksheets are completed by healthcare professionals, including nutritionists, nurses, and physicians.

A scoring schema of 0–4 points is utilized, consistent with the scoring used throughout cancer and in toxicity criteria, indicating normal or minimal impact on nutritional status or risk (0); mild impact (1); moderate impact (2); severe impact (3); and potentially life-threatening impact (4). Total PG-SGA score was primarily based on patient input rather than clinician evaluation. Total scores range from 0 to 59, with higher scores indicating poorer nutritional status. The PG-SGA guidelines suggest classification recommendations according to scoring ranges: a score of 0–1 indicates that there is “no nutritional intervention required at this time,” a score of 2–3 indicates that “patient education is potentially needed but without nutritional intervention,” while a score of 4–8 “requires intervention by the dietitian to assess malnutrition in conjunction with the nurse/physician as indicated by the symptoms scored,” and a score of ≥ 9 indicates a critical need for nutrition intervention [24].

2.3.4. Depression

Depression was evaluated using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) [25], a commonly used screening tool for assessing depressive symptoms in nonpsychiatric populations. In the Korean version of CES-D-10, respondents answer questions about their experience of depressive symptoms in the past week using four options: rarely (less than one day), sometimes (1–2 days), often (3–4 days), and always (5–7 days). Rarely and sometimes correspond to a score of 0, while often and always correspond to 1. A total score of 4 or higher on the 10 questions indicates the presence of depression [26]. The CES-D-10 demonstrated good internal consistency. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.88.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Saint Mary Hospital of C University in Seoul (approval no.: KC19QESE0563). The first author visited adult patients with acute leukemia who were admitted to the hospital for chemotherapy and met the inclusion criteria. The purpose and procedures of the study were explained and written informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to data collection. Participants visited the hospital before starting chemotherapy to complete the questionnaire. Ten days after completion of chemotherapy, they visited the hospital again to complete the same questionnaires that assessed their oral mucositis.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed using SPSS 28.0. The general and disease-related characteristics of the participants, along with the severity of oral mucositis, the symptoms experienced, the nutritional status, and depression before and after 10 days of chemotherapy, were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviations. Differences in symptoms experienced, nutritional status, and depression were analyzed according to the severity of oral mucositis and the stage of treatment before and after chemotherapy using a paired t-test, and one-way analysis of variance. Prior to parametric analyses, which included the paired t-test and one-way ANOVA, we assessed the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Both assumptions were met, enabling the use of parametric tests. Post hoc comparisons for the ANOVA were conducted using the Bonferroni correction method. Factors related to depression after chemotherapy were analyzed using multiple regression analysis. Statistical significance was reported at the conventional p < 0.05 level (two-tailed).

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

The mean age of the participants was 38.34 years (standard deviation = 13.42). Among them, 45.5% were not religious, 78.0% were married, 79.7% had completed high school education or higher, 58.5% were employed and 77.2% reported their subjective economic status as “middle.”

Ninety-one participants (74.0%) were diagnosed with AML and 32 (26.0%) had acute lymphocytic leukemia. Forty-one patients (33.3%) underwent remission-induction therapy, 66 (53.7%) underwent consolidation therapy, and 16 (13.0%) underwent remission therapy. Most of the patients (n = 120, 97.6%) underwent three or fewer rounds of chemotherapy. All participants received chemotherapy before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 62 (50.4) |

| Female | 61 (49.6) | |

| Age (years) | (Mean: 48.3 ± 13.42) | |

| 19–29 | 15 (12.1) | |

| 30–39 | 13 (10.6) | |

| 40–49 | 27 (22.0) | |

| 50–59 | 33 (26.8) | |

| 60–69 | 35 (28.5) | |

| Religion | Protestant | 32 (26.0) |

| Catholic | 13 (10.6) | |

| Buddhist | 17 (13.8) | |

| Other | 5 (4.1) | |

| None | 56 (45.5) | |

| Marital status | Single | 27 (22.0) |

| Married | 96 (78.0) | |

| Education | Elementary school | 5 (4.1) |

| Middle school | 20 (16.2) | |

| High school | 44 (35.8) | |

| University | 54 (43.9) | |

| Working status | Unemployed | 51 (41.5) |

| Full time | 72 (58.5) | |

| Diagnosis of disease | Acute lymphoid leukemia | 32 (26.0) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 91 (74.0) | |

| Treatment | Induction | 41 (33.3) |

| Consolidation | 66 (53.7) | |

| Reinduction | 16 (13.0) | |

| Number of treatments | 1 | 41 (33.3) |

| 2 | 37 (30.2) | |

| ≥ 3 | 45 (36.5) | |

3.2. Oral Mucositis, Experienced Symptoms, Nutritional Status, and Depression After Chemotherapy

The number of participants in the normal group, classified according to the WHO Mucositis Grading Scale, decreased from 118 (95.9%) before chemotherapy to 42 (34.2%) after chemotherapy. The number of patients in the moderate group increased from 5 (4.1%) before therapy to 71 (57.7%) after chemotherapy. The number of participants in the severe group increased from 0 (0%) before chemotherapy to 10 (8.1%) during the same period.

As shown in Table 2, nutritional status deteriorated significantly with an increasing grade of oral mucositis (p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis also demonstrated significant differences in nutritional status between all levels of oral mucositis (a < b < c). As oral mucositis worsened, the severity of symptoms (p = 0.001), discomfort (p = 0.009), muscle weakness (p = 0.040), and depression (p = 0.002) also worsened significantly. A post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in the severity of symptoms, discomfort, muscle weakness, and depression between only the normal and severe groups (a < c) but not between the moderate and severe groups. No significant differences were found in interference with daily activities (p = 0.120), diarrhea (p = 0.841), or skin problems (p = 0.384) with an increasing severity of oral mucositis.

| Variables | WHO oral mucositis status | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 42) | Moderate (n = 71) | Severe (n = 10) | |||

| Symptom experiences | |||||

| Symptom severity | 2.32 ± 1.54a | 3.07 ± 1.53 | 4.11 ± 0.87b | 6.87 | 0.001 |

| Symptom interference | 2.08 ± 1.46 | 2.40 ± 1.27 | 3.03 ± 1.45 | 2.15 | 0.120 |

| Discomfort | 5.26 ± 2.43a | 6.08 ± 2.31 | 7.70 ± 1.41b | 4.90 | 0.009 |

| Diarrhea | 3.14 ± 3.53 | 2.75 ± 3.64 | 3.10 ± 3.69 | 0.17 | 0.841 |

| Muscle weakness | 1.60 ± 2.34a | 2.34 ± 2.37 | 3.70 ± 3.23b | 3.29 | 0.040 |

| Skin problem | 2.50 ± 3.13 | 3.28 ± 3.35 | 3.70 ± 3.33 | 0.96 | 0.384 |

| Nutrition status | 14.90 ± 6.56a | 19.61 ± 6.79b | 26.90 ± 5.52c | 15.18 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 4.02 ± 3.31a | 5.39 ± 2.93 | 7.70 ± 1.94b | 6.76 | 0.002 |

- Note: Values are presented as means ± standard deviation. Different superscript letters in the same row indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, as determined using the Bonferroni test.

- Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

We also compared the differences in study variables before and after chemotherapy according to the leukemia type. Before chemotherapy, there were no significant differences in WHO grade, symptom severity, symptom interference, or depression scores between acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and AML patients. However, 10 days after chemotherapy, the WHO grade showed a significant difference, while other variables remained unchanged (Appendix A2).

3.3. Triage Malnutrition, Prevalence of Malnutrition, and Nutrition Impact Symptoms

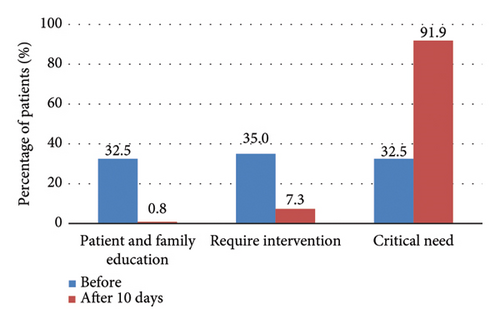

The changes in malnutrition classification among patients classified by PG-SGA are presented in Figure 1. The x-axis represents the PG-SGA triage categories, while the y-axis indicates the percentage of patients in each category. On day 10 of chemotherapy, the percentage of patients in the triage 2 group, indicating that patient education was potentially needed but without a requirement for nutrition intervention, decreased significantly from 32.5% to 0.8%. Conversely, the percentage of patients in the triage 4 group, indicating a critical need for nutrition intervention, increased dramatically from 32.5% to 91.9%. These results highlight the substantial shift in nutritional needs among patients undergoing chemotherapy.

The frequency of the symptoms of nutritional impact is shown in Table 3. The most prevalent symptoms of nutritional impact were pain, anorexia, and mouth sores after chemotherapy. Only 18 (14.6%) reported “no problem eating.” In total, 104 (84.6%) reported experiencing “pain,” 94 (74.6%) reported having “no appetite and no desire to eat,” and 80 (65%) reported having “mouth sores.” More than half of the participants reported experiencing these four from the 14 symptoms. PG-SGA point scores were significantly different between before and after chemotherapy (t = −16.51, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Nutrition impact symptoms | Baseline n (%) | After 10 days n (%) | Paired t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No problems eating | 90 (73.2%) | 18 (14.6%) | ||

| No appetite | 45 (36.6%) | 94 (76.4%) | ||

| Nausea | 28 (22.8%) | 54 (43.9%) | ||

| Vomiting | 7 (5.7%) | 38 (30.9%) | ||

| Constipation | 25 (20.3%) | 30 (24.4%) | ||

| Diarrhea | 10 (8.1%) | 56 (45.5%) | ||

| Mouth sores | 4 (3.3%) | 80 (65.0%) | ||

| Pain | 42 (34.1%) | 104 (84.6%) | ||

| Dry mouth | 16 (13.0%) | 55 (44.7%) | ||

| Have no taste | 3 (2.4%) | 22 (17.9%) | ||

| Smells bother me | 5 (4.1%) | 22 (17.9%) | ||

| Problem swallowing | 2 (1.6%) | 46 (37.4%) | ||

| Feel full quickly | 2 (1.6%) | 13 (10.6%) | ||

| Other | 4 (3.3%) | 9 (7.3%) | ||

| PG-SGA score (mean ± SD) | 7.40 ± 5.38 | 18.59 ± 7.35 | −16.51 | < 0.001 |

- Note: Patients could report more than one symptom. PG-SGA: Subjective Global Assessment.

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

3.4. Factors Affecting Depression After Chemotherapy

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to investigate the factors influencing depression in patients with acute leukemia (Table 4). The assumptions of the statistical model, including the ratio of cases to independent variables, normality, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, linearity, and absence of multicollinearity, were confirmed. In Model 1, patients who underwent consolidation therapy had higher depression scores compared to those who underwent induction and reinduction therapy (β = −2.04, p = 0.02). Model 1 explained 10.0% of the total variances. Model 2, adjusted for gender, age, leukemia type, and treatment status, revealed that symptom severity was associated with depression (β = 1.06, p < 0.001). Furthermore, among the symptoms of acute leukemia, muscle weakness and skin problems were associated with depression (β = 0.21, p = 0.015; β = 0.20, p < 0.001, respectively). The variables in this model 2 represented 67.0% of the variance in depression among patients with acute leukemia.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SD | t | p | Beta | SD | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 7.06 | 1.22 | 5.81 | < 0.001 | 2.44 | 0.93 | 2.62 | 0.01 |

| Gender (female) | 0.79 | 0.55 | 1.44 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.81 |

| Age | −0.21 | 0.21 | −0.99 | 0.33 | −0.13 | 0.14 | −0.95 | 0.34 |

| AML (vs. ALL) | −0.65 | 0.65 | −1.01 | 0.32 | −0.44 | 0.42 | −1.04 | 0.30 |

| Induction (vs. reinduction) | −0.11 | 0.89 | −0.12 | 0.91 | −0.82 | 0.58 | −1.43 | 0.16 |

| Consolidation (vs. reinduction) | −2.04 | 0.85 | −2.39 | 0.02 | −1.47 | 0.56 | −2.63 | 0.01 |

| Symptom severity | 1.06 | 0.22 | 4.90 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Discomfort | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.94 | 0.35 | ||||

| Diarrhea | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.75 | 0.46 | ||||

| Muscle weakness | 0.20 | 0.09 | 2.30 | 0.02 | ||||

| Skin problem | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.28 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Nutrition status | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.26 | 0.80 | ||||

| F(5, 122) = 3.77, p = 0.003 | F(11, 122) = 20.29, p < 0.001 | |||||||

| R2 = 0.10, adjusted R2 = 0.10 | R2 = 0.67, adjusted R2 = 0.64 | |||||||

- Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

This descriptive and comparative study investigated differences in oral mucositis, symptom experiences, nutritional status, and depression before and after 10 days of chemotherapy in patients with acute leukemia. In this study, 91 patients (74.0%) were diagnosed with AML and 32 (26.0%) with acute lymphocytic leukemia. These rates are in agreement with the annual statistics on domestic cancer incidents in South Korea [27].

In this study, the severity score for symptoms 10 days after chemotherapy was 2.90 (±1.56), and the interference score for symptoms was 2.34 (±1.36). In comparison, a study by Son [28], which used the same assessment tool for patients with hematologic malignancies, reported higher severity and interference scores of 3.46 (±2.27) and 3.74 (±2.44), respectively. While this study focused on patients undergoing chemotherapy prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Son [28] examined survivors of blood cancer who had already undergone transplantation. The differences in symptom severity and interference scores between this study and Son [28] may be attributed to variations in participant characteristics and the timing of assessments. This study reflects the acute side effects of chemotherapy administered before transplantation, whereas Son [28] likely captured the chronic impacts experienced by survivors post-transplantation. Moreover, high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation—common preconditioning treatments for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—are known to cause severe side effects such as oral mucositis [29]. These treatment-related factors may have also contributed to the observed discrepancies in scores.

As AML uses more aggressive treatments such as FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine, G-CSF) and high-dose chemotherapy, the incidence of oral mucositis is high at 50%–70% [8]. This may explain why patients with blood cancer who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation exhibited higher severity and interference scores of symptoms compared to participants in this study. In the assessment conducted 10 days after chemotherapy using the WHO Mucositis Grading Scale, 34 patients (27.6%) developed oral mucositis of grade 2 or higher accompanied by ulceration. This incidence was lower than that reported in a previous study [8]. This difference may be attributed to the fact that participants with neutropenia underwent an oral care protocol (including oral assessment, patient education, tooth brushing, and mouth washing methods) upon admission to the isolation unit to provide preventive oral nursing care.

In this study, most participants (n = 110, 89.4%) exhibited severe malnutrition with a PG-SGA score ≥ 9 on day 10 after chemotherapy. This finding is consistent with a study by So et al. [30], which reported a significant decrease in food intake among patients after 2 weeks of chemotherapy. In addition, their study found that 60.9% of patients with hematologic cancer discharged after finishing chemotherapy had poor nutritional status. Among the issues related to food intake, such as oral mucositis pain or swallowing difficulty, lack of appetite was the most reported (n = 94, 76.4%). In another study that used the same assessment tool, lack of appetite had the highest score of 4.83 (±3.58), with 55% of the total participants experiencing moderate to severe appetite loss, corroborating the findings of this study [31]. Common nutrient deficiencies observed in leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy include protein, vitamin D, iron, folate, vitamin B12, zinc, magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamin C. These deficiencies can exacerbate symptoms such as fatigue, immune dysfunction, delayed wound healing, and mood disturbances, highlighting the necessity for tailored nutritional interventions. These findings underscore the importance of nursing care in enhancing patients’ appetites. Nutrition triage recommendations include patient and family education, symptom management, and nutrition intervention such as additional food, oral nutrition supplements, and enteral or parenteral nutrition [32]. Moreover, recent studies have emphasized that timely nutritional interventions can improve not only the physical health of cancer patients but also their psychological well-being, further underlining the importance of holistic care approaches [33].

In this study, the depression scores increased significantly from 3.14 (±2.99) before chemotherapy to 5.11 (±3.14) after chemotherapy (t = −7.82, p < 0.001). CESD-10 scores of 4 or higher indicated the clinical presence of depression. Therefore, compared to before chemotherapy, depression worsened significantly 10 days after the end of chemotherapy. Among studies exploring the association between blood cancer and depression, one investigated the relationships between resilience, family support, anxiety, and depression [34], while another focused on the correlation between spiritual health and depression [16]. Another study examined the relationships among anxiety, depression, physical symptoms, and the need for nursing support [31]. These studies investigated variations in the severity of depression based on recurrence and explored the correlations between different variables. Sleep was inversely correlated with physical activity and positively correlated with fatigue. Thus, patients with fewer sleep impairments reported higher levels of physical activity, while those with more sleep problems experienced greater general fatigue [35]. Similarly, Park and Kong [36] reported that patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy often experienced sleep disturbances, which were influenced by symptoms of the disease, anxiety, depression, and patient activation levels. Therefore, they cannot be directly compared with this study, which examined changes in depression before and after chemotherapy and identified factors influencing depression. However, these findings collectively highlight the need for targeted psychological support interventions for patients undergoing chemotherapy to manage depression and improve overall treatment outcomes.

In this study, Model 2, used to identify the factors that influence depression, revealed that muscle weakening (β = 0.21, p = 0.015) and skin problems (β = 0.20, p = 0.002), which are symptoms of acute leukemia, accounted for 64% of the total variance. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that the greater the burden from physiological symptoms like cancer-related symptoms, fatigue, pain, and impaired functional status, the stronger the psychological response, such as depression and anxiety [37]. There are two possible explanations for this result. First, muscle weakness is a common symptom among cancer patients. Although fall prevention education is commonly provided in clinical settings, patients who experience falls despite such interventions often develop a fear of falling, leading to reduced confidence in their ability to prevent falls [38]. This diminished confidence may restrict their activity levels, increase social isolation, and reduce independence in daily activities, ultimately exacerbating depressive symptoms [39, 40].

Second, the association between skin problems and depression has also been confirmed in adult patients with atopic dermatitis, with women in their 30s and 40s with high social interactions reporting higher levels of depressive symptoms than men [41]. Furthermore, patients with blood cancer (the focus group in this study) typically experience relatively mild skin symptoms, such as rash or itching due to anticancer agents or antibiotics, compared to patients with atopic dermatitis.

These previous findings align with the results of this study, suggesting that skin problems are a potential factor that influences depression. Additionally, anxiety and depressive symptoms are associated with oral mucositis, which impacts overall health and oral health-related quality of life, thus aligning with the findings of de Arruda et al. [42]. Therefore, it is imperative to acknowledge and address the various physical symptoms experienced by patients with acute leukemia who have undergone chemotherapy. Future studies should also explore the long-term psychological impacts of these symptoms, including potential interventions to mitigate their effects on patient well-being.

A limitation of this study is the potential variability in the general condition of patients before chemotherapy, which may depend on the stage of treatment (remission induction, consolidation, or reinduction). During remission-induction therapy, patients showed higher severity scores compared to those undergoing other treatments. Therefore, future studies that focus specifically on this group of patients are warranted.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the occurrence of oral mucositis and other oral complications among individuals receiving outpatient chemotherapy treatment. Half of all patients who underwent outpatient chemotherapy had oral mucositis. Most patients with oral mucositis had Grade 1, and the most common oral complications included dry mouth, altered sense of taste, hoarseness, and difficulty eating. Significant risk factors for developing oral mucositis were advanced age, poor appetite, and duration of chemotherapy. Therefore, nurses should be trained in using specific and essential clinical care guidelines to support these patients. Furthermore, the findings highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, dentists, dietitians, and mental health professionals to address the interconnected challenges of oral complications, nutritional deficits, and psychological well-being. Implementing such a comprehensive care model can improve patient outcomes, enhance quality of life, and ensure better adherence to chemotherapy treatments.

6. Implications for Practice

Monitoring the nutritional status of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy presents a significant challenge for nurses. Patients with notable nutritional deficiencies or poor dietary intake, particularly those suffering from chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis require attention. A multidisciplinary approach is crucial for addressing the different issues, and it should involve collaboration with dietitians to develop tailored nutrition plans and consultation with oncologists to manage side effects. Such collaboration is essential for delivering comprehensive nursing care and emotional support aimed at improving patients’ nutritional status. The development of effective nursing interventions should be grounded in continuous review and research within these fields. Additionally, it is vital to provide detailed explanations of potential symptoms to patients who are hospitalized following an initial diagnosis of acute leukemia and are scheduled for remission-induction therapy. Such support should be provided alongside the necessary nursing care protocols.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Scholarship Grants in 2022.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study for sharing their experiences.

Appendix A: Treatment Protocols and Changes in Symptoms Before and After Chemotherapy in Participants With Acute Leukemia

| Phases | Acute myeloid leukemia | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

|---|---|---|

| Agent (days) | Agent (days) | |

| Induction |

|

|

| 1st Consolidation |

|

|

| 2nd Consolidation |

|

Mcavd (D1∼14) |

| Reinduction |

|

|

| Salvage |

|

|

| Variables | ALL | AML | t or x2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before chemotherapy | WHO grade | Normal | 31 | 87 | 0.09 | 075 |

| Moderate | 1 | 594 | ||||

| Symptom severity | 1.21 ± 1.08 | 1.08 ± 1.17 | 0.51 | 0.61 | ||

| Symptom interference | 5.03 ± 5.69 | 4.17 ± 5.08 | 0.79 | 0.43 | ||

| Depression | 14.78 ± 5.60 | 13.68 ± 4.22 | 1.01 | 0.32 | ||

| 10 days after chemotherapy | WHO grade | Normal | 1 | 27 | 8.15 | 0.02 |

| Moderate | 12 | 59 | ||||

| Severe | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Symptom severity | 3.22 ± 1.53 | 2.79 ± 1.58 | 1.31 | 0.19 | ||

| Symptom interference | 13.13 ± 7.92 | 14.43 ± 8.30 | −0.77 | 0.44 | ||

| Depression | 5.63 ± 3.23 | 4.93 ± 3.12 | 1.07 | 0.29 | ||

- Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoid leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.