Anxiety and Depression in Patients Receiving Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Their Caregivers: A Dyadic Longitudinal Study

Abstract

Introduction: Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) recipients and their caregivers may experience psychological distress. This study aimed to evaluate anxiety and depression in patients and caregivers throughout the HSCT process. As a secondary objective, we explored the association between anxiety and depression in patient and caregiver over the same period and compared anxiety and depression according to sociodemographic factors and whether HSCT was homebound or hospitalised.

Methodology: Longitudinal descriptive study. Seventy-two HSCT patients and their caregivers were consecutively included at a Spanish hospital between October 2019 and February 2021. The HADS instrument was used to assess anxiety and depression at six time-points, including pre-HSCT, the acute period and one-year follow-up. An adjusted linear mixed model assessed variable changes over time-points and a correlational analysis evaluated the relationship between anxiety and depression. To detect differences between groups over time, a linear mixed model was adjusted.

Results: Participants’ anxiety levels were high at all time-points and consistently higher among caregivers than patients. Patients and caregivers’ depression levels were low pre-HSCT and increased significantly during hospitalisation. Patients’ depression decreased during follow-up but remained stable among caregivers. We observed moderate positive correlations between patient and caregiver anxiety or depression at all time-points except pre-HSCT. Caring for other dependents increased depression in patients and being female increased both anxiety and depression in caregivers. Residing in social housing increased patient anxiety and depression and caregiver depression.

Conclusions: Diverging trajectories for patient and caregiver anxiety and depression were observed. Caregivers showed higher levels of anxiety than patients throughout the HSCT process and higher levels of depression from 3 months after HSCT. Admission was a critical time that increased depression in both. This study supports the need for new intervention approaches in prevention, early detection and treatment of anxiety and depression in patients receiving HSCT and their caregivers.

1. Introduction

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an intensive treatment offered to patients with high-risk malignant or nonmalignant diseases [1]. It can be autologous (auto-HSCT) when the progenitors are from the same patient or allogeneic (allo-HSCT) when obtained from a donor. Despite being potentially curative, treatment is still associated with high risk of mortality and comorbidities in the short and long term [2]. The course of disease for patients receiving HSCT is variable and unclear, with care demands changing according to the manifestation of complications [3]. Although care of these patients has traditionally taken place in hospital, outpatient and homecare is increasingly common [4]. The focus of research in the onco-haematological context is shifting from the individual to the patient-caregiver dyad as studies show interdependence in psychological morbidity [5].

HSCT is linked to psychological and psychosocial sequelae, including anxiety, depression, fatigue, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexual dysfunction, existential stress and financial toxicity [6–9]. Pre-HSCT anxiety and depression have been identified in up to 56% and 52% of patients, respectively [10, 11]. During hospitalisation, Seo et al. [11] observed the inception of anxiety in 27% of patients, and depression in 30%. In the long term, anxiety and depression prevalence of 14.9% and 13.6% have been reported, respectively [12]. In our context, Prieto et al. [13] showed how approximately 20% of patients developed clinically significant psychiatric disorders during hospitalisation for HSCT. Among HSCT patients, negative emotional states may hinder them from engaging in healthy behaviours [14] and psychological distress is related to poorer health outcomes, including higher mortality [15, 16]. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of patients will need care for years following HSCT [17], either due to long-term side effects (particularly in allo-HSCT subjects) or disease relapse requiring new lines of treatment.

Having an informal or family caregiver dedicated to looking after the patient for at least the first 100 days post-transplantation, offering instrumental and emotional support, is required by most transplant centres [4, 18]. In fact, not having a caregiver 24/7 precludes the possibility of conducting homebound HSCT [4]. Being the caregiver of a transplant patient is highly demanding, making it difficult to meet one’s own physical and emotional needs [19]. In addition to the management of day-to-day care activities, such as monitoring medication, coping with complex symptoms, preventing infections and accompanying the patient on medical visits, the caregiver must contain their own fears and uncertainties regarding the patient’s health and prognosis [20]. In many cases, the patients and caregivers must relocate to be near the transplant centre, separating them from their usual environment. Due to the previously mentioned factors, caregivers may present emotional distress, including anxiety and depression that can rise to a pre-HSCT prevalence of 56% and 24.28%, respectively [21], whereas depression levels can increase threefold to 25.5% prevalence during hospitalisation [22]. Furthermore, in the long term, 14% of caregivers report depression [17, 23] and around 6.6% PTSD [24]. Psychological distress has been observed to be higher when caregivers are female [23], have financial difficulties [23, 25], experience higher degrees of loneliness [3] or use avoidant coping strategies [26].

The few longitudinal studies carried out to date that assessed anxiety and depression during HSCT focussed on the acute period [22] or on medium-term follow-up [25], revealing the need to analyse the entire course of HSCT. Reviews of the literature on the issue recommend that studies cover the entire course of HSCT, with particular attention on reciprocal effects in the patient-caregiver dyad and the particularities of homecare HSCT [19, 26]. This would allow the identification of critical points where heightened distress may occur [27], and where psychological interventions could be more beneficial. This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to assess HSCT patient-caregiver dyad anxiety and depression at 6 time-points in the HSCT process from hospitalisation to 1 year post-HSCT. Our main aim was to evaluate anxiety and depression in both caregiver and patient throughout the HSCT process. Secondly, the association between anxiety and depression in patient and caregiver was explored over the same period and the course of anxiety and depression was compared between groups according to sociodemographic factors and whether the patient received homecare or hospitalised HSCT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Study Setting

A longitudinal prospective study with participant inclusion was carried out between October 2019 and February 2021 with conclusion of patient follow-up in February 2022. This study was conducted in a tertiary university hospital in Barcelona (Spain) which provides both autologous and allogeneic transplants in homecare and hospitalisation programs. For a homecare HSCT to be performed, the patient-caregiver dyad must live within 30 min of the hospital during the transplant period. Patients receiving allogeneic HSCT must reside within 60 min of the hospital for a period of 6–12 months. Thus, patients and caregivers who live far from the hospital must relocate to Barcelona, renting a flat or living with acquaintances. When accommodation is unaffordable, the hospital organises social housing. This study was performed and reported following the STROBE statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [28].

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the centre’s Research Ethics Committee (Ref: HCB/2018/1127) and carried out in accordance with the basic ethical principles for clinical research established by the Declaration of Helsinki (current version: Fortaleza, Brazil, October, 2013) and Spanish Law 14/2007 of the third of July on Biomedical Research. Once participants were fully informed about the nature of the study and their right to withdraw from it at any time, they signed the consent form.

2.3. Participants

Nonprobabilistic consecutive participation was offered to patients waiting for homecare or hospitalised HSCT (autologous and allogeneic) and their caregivers who met inclusion criteria up to a minimum of 123 HSCTs. The sample size was calculated based on the average number of transplants performed annually at the study hospital between 2014 and 2018, which was 123. Due to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, the inclusion period was 16 months. The decision to include both autologous and allogeneic HSCTs was based on previous study findings that similar caregiver burden exists with respect to the acute recovery period [29] and the long-term mental aspect of perceived quality of life [17]. Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: older than 18 years with a primary caregiver identified by the HSCT team. Exclusion criteria were second allo-HSCT, lack of comprehension of spoken and/or written Spanish and motive for HSCT being primary amyloidosis, Crohn’s disease or autoimmune neurological diseases. The caregiver inclusion criteria were being older than 18 years while exclusion criteria were lack of comprehension of spoken and/or written Spanish or being a professional caregiver.

2.4. Procedures, Data Collection and Variables

During the first pre-HSCT visit, the HSCT advanced practice nurse established whether the patient met inclusion/exclusion criteria, explained the study aims, methods and implications verbally and in writing and invited the patient-caregiver dyad to participate. On acceptance, the nurse requested signed informed consent. The first questionnaires were then administered during this visit (T0). Once the transplant was performed, further questionnaires were completed and data were collected on day +7 (auto-HSCT) and +10 (allo-HSCT) (T1) and on day +14 (auto-HSCT) and +21 (allo-HSCT) (T2) at the haematology ward or at home according to HSCT setting. Subsequently, coinciding with hospital visits, data were gathered at 3, 6 and 12 months post-HSCT (T3, T4 and T5, respectively).

The time-points were strategically defined to represent the course of recovery and the critical phases that the HSCT patient and caregiver would go through. Thus, the pre-HSCT phase (T0) was introduced. During the hospitalisation period, two time-points were established, with different scheduled days for autologous or allogeneic HSCT. The first (T1) represents the peak period for complications and T2 the moment when the patient’s condition tends to improve and planning for discharge begins. Finally, three medium-term supervision points were programed (T3, T4 and T5).

The patient’s HSCT-related and clinical variables were obtained from medical records. Patients and caregivers responded to an ad hoc survey at T0 designed to gather sociodemographic data. Participants’ levels of anxiety and depression were assessed at each time-point using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) instrument.

2.5. Measures

The HADS assesses potential cases of anxiety and depression. The scale contains two 7-item subscales which measure mutually exclusive levels of anxiety and depression, with results ranging from 0 to 21. A score lower than 7 is considered noncase, 8–10 borderline and 11 or higher as a confirmed case of anxiety and depression [30]. The Spanish version’s internal consistency, assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.90 for the full scale, 0.84 for the depression subscale and 0.85 for the anxiety subscale. Specificity was 87% and 85% for the depression and anxiety module, respectively, and sensitivity was 72% and 80% for the depression and anxiety module, respectively [31]. Permission for use was granted.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis of patient and caregiver characteristics was performed. Means (standard deviations) were used for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. Characteristics of subjects who completed all the questionnaires and those who did not were compared using the chi-squared or Fisher’s test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney test for quantitative variables. A linear mixed model was adjusted that took repeated measures into account for assessment of scale changes over visits. In this model, the differences in the scale scores between a specific follow-up time and baseline were tested. Furthermore, the trends for participants’ percentages of anxiety or depression, classified as normal, borderline or pathological, were studied. Finally, the HADS scale Pearson correlations between patient and caregiver anxiety and depression at different times were calculated. To detect differences in the evolution of scale data between participants according to sociodemographic factors and whether the HSCT was conducted at home or in hospital, scale means were calculated and a linear mixed model was adjusted to take into account the repeated measures between individuals. The existence of interaction between type of participant and time was contrasted to see whether temporal differences were distinct between groups. HADS missing data were replaced the mean of each person, if they did not exceed 20% for each subscale [32]. All analyses were performed using R Version 4.2.2 (2022).

3. Results

Of the 127 HSCTs eligible to participate in the study, 10 did not meet clinical criteria, 8 presented a significant language barrier and 8 did not have a primary caregiver. The remaining 101 patient-caregiver dyads were invited to take part and, of these, 21 declined to participate, 6 were lost to follow-up and 2 patients died before HSCT. Seventy-two dyads were finally included. Rate of participation at each time point varied between 67% and 89% and 9 patients died during follow-up (12.5%). No evidence of differences (p < 0.05) between variables was found when comparing participants who completed all questionnaires with those who did not.

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Participants’ sociodemographic and clinical information showed that patients’ mean age was 52 years (SD 12.6) and the majority (63.9%) were men. Twenty-six (36.1%) were diagnosed with leukaemia. Thirty-eight (52.8%) received allo-HSCT and thirty-six (50%) received HSCT at home. Caregivers’ mean age was 54.4 years (SD 13.8) and the majority (64.8%) were women. Twenty-three (38.3%) were in active employment. Twenty (37.7%) had children under 21 years old and 18 (41.9%) cared for additional dependents. Thirty-seven (52.1%) had to move their residence near the hospital and, of these, 23 (63.9%) required social housing (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Patients | n | Caregivers | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 (12.6) | 72 | 54.4 (13.8) | 53 |

| Sex | 72 | |||

| Male | 46 (63.9%) | 25 (35.2%) | 71 | |

| Female | 26 (36.1%) | 46 (64.8%) | ||

| Educational level | 66 | 53 | ||

| Primary | 13 (19.7%) | 10 (18.9%) | ||

| Secondary | 22 (33.3%) | 20 (37.7%) | ||

| Higher education | 31 (47%) | 23 (43.4%) | ||

| Country of birth | 72 | 61 | ||

| Spain | 65 (90.3%) | 56 (91.8%) | ||

| Others | 7 (9.7%) | 5 (8.2%) | ||

| Employment status | 68 | 60 | ||

| Active | 7 (10.3%) | 14 (23.3%) | ||

| Flexible/reduced working hours | 9 (15%) | |||

| Paid leave | 35 (51.5%) | 9 (15%) | ||

| Unemployment benefit | 4 (5.9%) | 4 (6.7%) | ||

| Other | 22 (32.4%) | 24 (40%) | ||

| Annual family incomes | 56 | 51 | ||

| < €20,000 | 15 (26.8%) | 16 (31.4%) | ||

| €20,000–50,000 | 34 (60.7%) | 30 (58.8%) | ||

| > €50,000 | 7 (12.5%) | 5 (9.8%) | ||

| Relationship with caregiver | 72 | |||

| Partner | 47 (65.3%) | |||

| Son/daughter | 6 (8.3%) | |||

| Father/mother | 15 (20.8%) | |||

| Others | 4 (5.6%) | |||

| Offspring under 21 years | 71 | 53 | ||

| Without young children | 42 (59.2%) | 33 (62.3%) | ||

| With young children | 29 (40.8%) | 20 (37.7%) | ||

| Caring for dependents | 59 | 43 | ||

| No dependents | 32 (54.2%) | 25 (58.1%) | ||

| Caring for dependents | 27 (45.8%) | 18 (41.9%) | ||

| Relocation due to HSCT | 72 | 71 | ||

| No | 32 (44.4%) | 34 (47.9%) | ||

| Yes | 40 (55.6%) | 37 (52.1%) | ||

| Place of residence if relocated: | 40 | 36 | ||

| Social housing | 23 (57.5%) | 23 (63.9%) | ||

| Family flat | 8 (20%) | 6 (16.7%) | ||

| Others1 | 9 (22.5%) | 7 (19.4%) | ||

| Diagnosis | 72 | |||

| Others | 8 (11.1%) | |||

| Leukaemias | 26 (36.1%) | |||

| Lymphomas | 15 (20.8%) | |||

| Multiple myeloma | 23 (31.9%) | |||

| Type of HSCT | 72 | |||

| Allo-HSC | 38 (52.8%) | |||

| Auto-HSCT | 34 (47.2%) | |||

| HSCT type | 72 | |||

| Home setting HSCT | 36 (50%) | |||

| HSCT—admitted | 36 (50%) | |||

| Total readmissions | 72 | |||

| No readmissions | 39 (54.2%) | |||

| 1-2 readmissions | 22 (30.6%) | |||

| 3 or more readmissions | 11 (15.3%) | |||

| Exitus 12 months | 72 | |||

| No | 63 (87.5%) | |||

| Yes | 9 (12.5%) |

- Note: Italic values are the total of responses for each item.

- 1Rented flat, others.

3.2. Course of Patient and Caregiver Anxiety and Depression

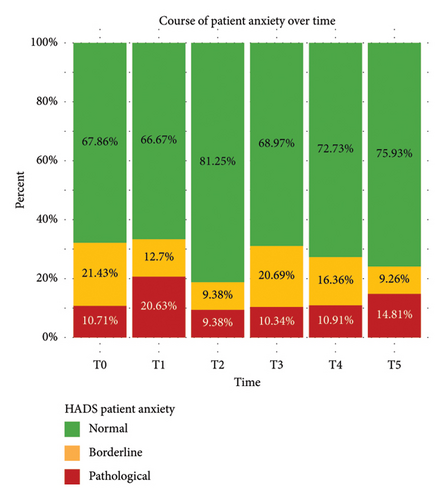

Patient and caregiver anxiety and depression data are shown in means (Table 2) and percentages (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4) indicating whether they are borderline or confirmed cases. Patient-reported anxiety fluctuated over the study period. Mean patient anxiety was 6.2 (SD 3.2) pre-HSCT, and in terms of prevalence, 32.1% met anxiety criteria, with these levels remaining unchanged during admission (T1). As discharge approached (T2), mean anxiety decreased to 5.2 (SD 3.5) in 18.7% of patients. At medium-term follow-up, the proportion of patients meeting anxiety criteria rose to 31% at 3 months before decreasing again, as time since HSCT elapsed, to 24.1% at 12 months, with mean levels of 5.8 (SD 4.4) at 12 months. As for patients’ depression, 12.5% met depression criteria prior to HSCT. Incidence increased to 36.5% during the acute period, with mean levels of depression rising from 3.7 (SD 3) pre-HSCT to 5.9 (SD 4.3) (p < 0.001) at T1. At 3 months, prevalence had fallen to 19% and stabilised at 16.7% at 12 months, with mean levels in the HADS subscale of 4.1 (SD 3.9).

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety (HADS instrument) | ||||||

| Patient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Caregiver |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Depression (HADS instrument) | ||||||

| Patient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Caregiver |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

- Note: N for the first line values described, mean (SD) for the second line values, difference to T0 for the third line values, and p value for the forth line values. Bold values mean no significant difference in terms of SD evolution from T0.

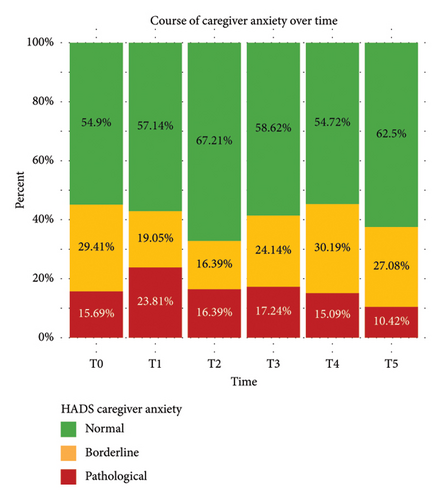

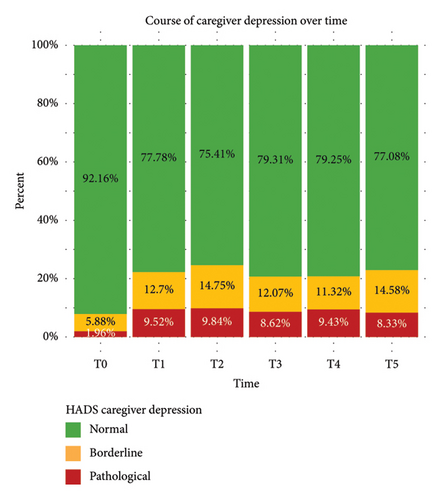

With regard to caregivers, 45.1% fulfilled anxiety criteria prior to HSCT. Values remained around 40% throughout follow-up, except for the time close to patient discharge (T2) when incidence decreased to 32.8%. Mean levels of anxiety pre-HSCT were 6.7 (SD. 3.5) and remained stable with no statistically significant differences observed at any time-point. 7.8% of caregivers met depression criteria prior to HSCT with mean depression levels of 3.8 (SD 2.8). This proportion increased to 24.6% during the acute period and remained stable around 20% at all other time-points. As for mean depression levels, these increased to 4.8 (SD 3.7) at T1 (p.0.071) and 4.8 (SD 4) at T2 (p.0.021) and remained stable at the other time-points. Comparing patient and caregiver anxiety and depression results, it can be observed that caregivers scored, overall, 0.81 points higher on HADS-anxiety (p.0.109), while no significant differences were noted in levels of depression.

3.3. Associations Between Patient and Caregiver Anxiety and Depression Over the Study Period

Correlational analysis (Table 3) showed moderate positive correlations between patient and caregiver anxiety (r: 0.50–0.68) and between patient and caregiver depression (r = 0.40–0.65) at all time-points except pre-HSCT. Moderate positive correlations were also observed between patient anxiety and caregiver depression (r = 0.42–0.66) at time-points T1–T4, along with moderate positive correlations between patient depression and caregiver anxiety (r: 0.45–0.57) at time-points T2–T5.

|

- Note: N = 72. Missing data excluded. Cells in dark yellow: patient anxiety and caregiver anxiety, patient depression and caregiver depression, at T0–T5. Cells in light yellow: patient anxiety and caregiver depression, and patient depression and caregiver anxiety, at T0–T5. In bold: r > 0.6 statistically significant.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.001.

3.4. Factors Influencing Course of Anxiety and Depression

No differences were observed in patients′ course of anxiety and depression levels based on their sex, whether they had young children, or whether their caregivers cared for young children or other dependents. While anxiety was not affected, patients who cared for dependents were 2.26 points higher in depression (p.0.001). Among patients who had to relocate due to HSCT, those living in social housing were 1.71 points higher in anxiety (p.0.047) and 1.79 points higher in depression (p.0.036) compared to those living in other types of accommodation.

In caregivers, females were 2.44 points higher in anxiety (p.0.002) and 1.47 points higher in depression (p.0.031) than male caregivers. No differences were observed in anxiety or depression levels based on whether they cared for young children or other dependents. Among caregivers who had to relocate due to HSCT, those living in social housing were 2.38 points higher in depression (p.0.036), whereas anxiety levels remained similar.

When comparing the course of anxiety and depression levels between hospitalised or homecare HSCTs, no significant differences were observed in either patients or caregivers.

4. Discussion

This study describes the course of anxiety and depression in both HSCT patients and their caregivers throughout the first year post-HSCT. As indicated by Langer et al. [26], understanding the course of emotional health over HSCT is fundamental to the development, adaptation and fine-tuning of interventions designed to optimise the functioning of patients and caregivers. There is evidence that psychosocial interventions are effective in patients [8, 33] and caregivers [4, 34, 35] and should be offered to both members of the dyad.

4.1. Course of Anxiety and Depression

Our study provides further evidence that levels of anxiety and depression in patients and caregivers are worryingly high during both HSCT and follow-up [8]. Pre-HSCT anxiety levels in patients were 32.1% in our sample, intermediate values with respect to the range found in the literature, which varies between 17% and 56% [10, 36]. These levels of anxiety may be related to the anticipation of receiving treatment, uncertainty regarding the procedure and its effectiveness and the possible appearance of side effects. This should concern us, as pre-HSCT anxiety is associated with psychological issues during and post-HSCT [8]. Anxiety levels remained high at T1 (33.3%) and decreased at T2 (18.7%). El-Jawahri et al. [22] similarly noted how anxiety levels remained stable from pre-HSCT to a week post-HSCT. In contrast, Seo et al. [11] reported an increase in levels 1-week post-HSCT followed by a reduction at day 14 post-HSCT. This improvement around 14 days post-HSCT may be explained by the fact that adverse symptoms resulting from HSCT typically start to subside and planning for discharge begins. It could be hypothesised that relief at having overcome the acute phase reduced patients’ levels of anxiety. Despite a gradual decrease in the incidence of anxiety from T3–T5, 12 months later, there was still an anxiety prevalence of 24.07%, a finding that is in agreement with long-term studies [7, 12].

Pre-HSCT depression incidence in patients was 12.5%. There is high variability in the prevalence of pre-HSCT depression in the literature, which ranges from 5% to 52% [11, 36], probably due to the use of different diagnostic instruments. Regarding the acute phase of HSCT, a peak in incidence was observed at T2 and an improvement at T3, similar to that reported in other contexts [11, 22]. In other studies, depression during hospitalisation has been associated with longer stays, increased mortality, anxiety-depressive symptoms and post-HSCT PTSD [15, 37], so these results should concern us. In the sample analysed, prevalence of patient depression tended to decline gradually throughout follow-up, although it was still 16.7% 12 months post-HSCT. Once again, the consequences of depression after HSCT, including poor treatment adherence, worsening survival rates and low quality of life [8], emphasise the importance of these results and the need to prioritise the implementation of interventions to manage and reduce the prevalence of depression.

In our study, 45.1% of caregivers met criteria for anxiety cases pre-HSCT, consistent with figures in the literature of between 30% and 56% [21, 36]. In contrast to the findings reported by El-Jawahri et al. [22], caregivers in our sample tended to improve anxiety results during admission, reaching 32.8% at T3 and matching the lowest incidence of patient anxiety, which could be related to relief at having overcome the acute phase of HSCT. Caregiver anxiety results worsened during follow-up, with an anxiety prevalence of 37.5% recorded at 1-year post-HSCT, in accordance with the observations of Sannes et al. [25].

As was the case with patients, pre-HSCT depression prevalence among caregivers was low (7.8%), while the literature shows great variability in reported levels, ranging from 5% to 24.3% [21, 36]. In our sample, caregivers meeting depression criteria presented an almost threefold increase during the first weeks post-HSCT, and this percentage did not decrease during follow-up, which contrasted with the gradual improvement observed in patients’ results. While El-Jawahri et al. [22] reported an increase in mean caregiver depression levels, as observed in our sample, Sannes et al. [25] found that levels of depression did not differ from pre-HSCT to 6 months later. It was of concern to us that caregivers showed a prevalence of depression of 22.9% at 1 year post-HSCT and hypothesised that this prevalence could persist for years following HSCT, considering results reported in other contexts years after HSCT [17, 23].

In general, caregivers show a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms throughout the process, and more depressive symptoms from 3 months post-HSCT compared with the patients in their care. Other studies have also highlighted how emotional distress, including PTSD, is worse among caregivers [24, 36] and is associated with unmet needs [38, 39]. With respect to depression in both patients and caregivers, our results clearly show how the acute period is critical in the development of depression, the symptoms of which do not diminish over time. Thus, admission should be considered a crucial moment for early detection and initiation of depression prevention programmes.

4.2. Associations Between Patient and Caregiver Anxiety and Depression

A moderate association between patient and caregiver anxiety was observed at all time-points except the pre-HSCT assessment. A moderate association was observed between patient and caregiver depression at time-points T1–T4. Patient anxiety also showed moderate associations with caregiver depression at time-points T1–T4 and patient depression and caregiver anxiety at time-points T2–T5. It could therefore be inferred that patient and caregiver mental health are related, except in the pre-HSCT setting. These results are in agreement with others that postulate that patient and caregiver psychological functioning are inextricably linked [25, 40], and highlight the importance of meeting the needs of both actors [39]. As such, support for authors who propose reorienting patient interventions towards the patient-caregiver dyad appears warranted.

Posluszny et al. [36] also found no associations between patient and caregiver anxiety and depression in the pre-HSCT period, while they did observe associations in levels of cancer-related distress. We hypothesise that the lack of correlation in the pre-HSCT may be because patient and caregiver are in different psychological adaptation phases at this point. While the patient has usually already accepted the ‘sick’ role, not working, and delegating other responsibilities, they perceive HSCT as an encouraging option and a possible cure. In contrast, the caregiver, who is made aware from the first visit of the magnitude of their role during HSCT, may feel overwhelmed by the fear of not knowing how to manage complications, the looming burden of responsibilities and the organisation of their other life obligations.

4.3. Factors Influencing Course of Anxiety and Depression

In line with other studies [41], our sample consisted mainly of male patients (63.9%) and female caregivers (64.8%). Nevertheless, the percentages of female caregivers were lower than in other studies, where females represented more than 75% of their samples [21, 42, 43]. Studies have shown that female caregivers experience lower levels of quality of life [17], greater emotional distress [44] and higher caregiver burden [26]. In this study, we confirm these data, observing higher levels of anxiety and depression in female caregivers.

Although a significant proportion of participants cared for other family members, caring for other dependents only increased depression levels in patients, whereas counterintuitively it did not affect caregiver psychological well-being. Interestingly, in participants that had to relocate due to HSCT, living in social housing (rather than sharing with relatives or renting an apartment) led to higher levels of depression in both patients and caregivers and higher anxiety levels in patients. We can hypothesise that living in social housing, sometimes having to share accommodation, may increase the feelings of separation, but these hypotheses should be further studied using qualitative methodologies.

No differences were observed between hospitalised or homecare patients and caregivers in anxiety and depression levels or in the development of these levels over time. These results support the continuity and expansion of home-based HSCT programmes, as studies confirm that they are safe and feasible, with similar results to hospitalised programmes in terms of mortality [45], fewer complications, lower costs [45, 46] and similar or better quality of life results [45, 47]. Although studies including homecare HSCT caregivers are scarce [4, 48], other study findings show similar results in terms of burden during the recovery period [29], or long-term mental aspects of perceived quality of life [17].

4.4. Limitations

This study has a limitation due to its single-centre analysis; therefore, the results cannot be generalised to other contexts. In addition, various dyads declined to participate, giving rise to questions on whether these nonparticipants may have presented different results in levels of anxiety and depression. Separately, dyads that could not be included due to language barriers may feel less supported due to communication difficulties, and their situation should be assessed in further studies, ideally triangulating the results through the use of qualitative analyses using phenomenological methodology.

Despite the assistance of a study coordinator who contacted participants by telephone to remind them to return completed surveys, rates of participation varied throughout the study period. We attributed this to the exhaustion that participants experienced at certain times during the HSCT process when they were required to attend numerous medical appointments and complete other questionnaires. No differences were found in the results between respondent and nonrespondent data. Finally, the study was conducted, in part, during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, which limited the number of caregiver visits during hospitalisation and may have increased participants’ feelings of isolation and loneliness.

4.5. Contributions to Clinical Practice and Future Research

The success of HSCT programs depends to a large extent on the figure of the caregiver and their emotional well-being, although it is noteworthy that screening of caregivers’ mental health is not established in the majority of HSCT programmes. Due to the levels of anxiety reported in pre-HSCT, this would be an appropriate moment to carry out preliminary screening and detect vulnerable dyads. This screening should be holistic, taking into account personal factors, mental health and individual, social and economic resources. Once the HSCT has been carried out, routine mental health screenings should be instituted. Specifically, the results of this study show how admission is a critical point in detection and early initiation of treatment for depression in both patients and caregivers. Furthermore, psychosocial interventions should be established for both patients and caregivers, and due to the 6 different time assessments, this study may help professionals decide when would be the best time to apply each intervention, facilitating targeted implementation and optimising allocated resources.

Regarding future lines of research, it is essential to comprehend the particular needs of more vulnerable groups, such as patients and caregivers with language barriers or the economically disadvantaged. More studies addressing the specific requirements associated with homebound HSCTs are also necessary as these programmes increase in haematology care. The impact of factors such as residence in social housing should also be considered. Finally, it seems crucial to continue the trial and implementation of interventions aiming to enhance quality of life and mental health [34, 35, 49], establishing the most appropriate and efficient content, delivery method and frequency [4] along with analysis of their effectiveness once implemented in daily clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Heightened psychological distress at all time-points was observed in both patients and caregivers. Caregivers showed a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms throughout the HSCT process and more depressive symptoms from 3 months on than was observed in the patients in their care. Admission was a critical moment that increased depression levels in both. It should be noted that in this study, T2 (+14 days post-auto-HSCT, +21 days post-allo-HSCT) was the time of lowest anxiety for patient and caregiver, although, at the same time, it was the point of greatest association between patient and caregiver anxiety, patient and caregiver depression and patient anxiety and caregiver depression. No differences were observed between homecare and hospitalised HSCT recipients or their caregivers. Caring for other dependents increased depression in patients and being female increased both anxiety and depression in caregivers. Residing in social housing increased patient anxiety and depression and caregiver depression. This study supports the need for new intervention approaches in prevention, early detection and treatment of anxiety and depression in patients receiving HSCT and their caregivers.

Disclosure

The funding entity had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Arianna Rosich-Soteras: conceptualisation; methodology; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; project administration and writing – original draft. Carla Ramos-Serrano: data curation and writing – review and editing. Anna Serrahima-Mackay: conceptualisation; methodology; data curation and writing – review and editing. Cristina Gallego Miralles: conceptualisation; methodology; data curation and writing – review and editing. Teresa Solano Moliner: conceptualisation; methodology and writing – review and editing. Núria Jaramillo Forcada: data curation and writing – review and editing. Laia Guardia Roca: data curation and writing – review and editing. Ariadna Domenech: data curation; resources and writing – review and editing. Adelaida Zabalegui: conceptualisation; methodology; formal analysis; supervision and writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author was supported by a grant from the Fundació Catalunya-La Pedrera to be able to dedicate himself exclusively to data analysis and manuscript writing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the patients and caregivers for their participation in the study and our sincere appreciation to the centre professionals for their collaboration in the administration and collection of surveys. We also thank Stephen Kelly for language editing services.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.