Patient–Professional and Interprofessional Communication Barriers in Cancer-Related Fatigue Management: A Monocentric Focus-Group Study Among Multidisciplinary Healthcare Professionals

Abstract

Background: Unfavorable patient–professional and interprofessional communication have been identified as barriers to guideline-oriented, effective care of cancer-related fatigue (CRF).

Objectives: To illuminate these interactional challenges, this study aimed to explore the perceptions of healthcare professionals (HCPs) regarding (a) handling patients with CRF, (b) challenges in patients’ everyday life, and (c) suggestions to improve CRF management.

Methods: Two focus groups were recruited at the University Hospital Würzburg, Germany. Participants were HCPs working with cancer patients in the fields of medicine (n = 4), nursing (n = 3), and psycho-oncology (n = 4). Data were subjected to qualitative content analysis.

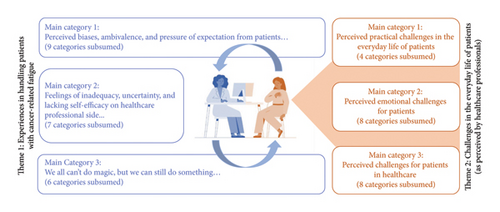

Results: A circular model was generated, illustrating the potential interaction between HCPs and patients with CRF from the HCP perspective. Concerns of HCPs, such as low self-efficacy in counseling on CRF and feelings of inadequacy through lack of feedback, interplay with patients’ suffering, resulting frustration, and pressure of expectation among others. This complicates empathic exchange, which HCPs actually highlight to meet patients’ needs and realize effective CRF management. To improve CRF management, HCPs suggested implementing standardized operating procedures to clarify responsibilities and to promote interprofessional collaboration in CRF care. Further, they expressed the need for professional training on CRF and on how to communicate with patients in this respect. Additionally, HCPs pointed out the necessity of cultivating reflective practice as HCPs to enhance empathy toward patients presenting CRF.

Conclusions: The interprofessional focus-group discussions improved our understanding of the challenges HCPs may perceive in managing CRF, outlined tasks on the institutional level to be addressed in the future, and provided suggestions for immediate adjustments on the individual level.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04921644

1. Introduction

Knowledge concerning the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) has grown exponentially over the last few years [1–3]. Defined as the “distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer and/or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity, and significantly interferes with usual functioning” [4], CRF makes patients feel considerably restricted in their daily functioning and quality of life [5–7]. A larger proportion of cancer patients present CRF symptoms while undergoing cancer treatment, whereas one-third still suffer from CRF 3 years after diagnosis [1, 2, 8]. Thus, healthcare professionals (HCPs) working with oncological patients frequently encounter this side effect. Nevertheless, a number of studies have indicated that patients suffering from CRF lack adequate care, even though corresponding clinical practice guidelines such as those from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [9] or the Canadian Association for Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) [10] and treatment options with a high level of evidence are now available [11–16].

Interprofessional collaboration in cancer care, if successfully realized, could increase evidence-based treatment decisions as well as HCP competence [17]. However, only few studies have assessed the HCPs’ perspective on the shortcomings in practical CRF management. To illuminate underlying causes, Jones et al. [18] recently conducted focus-group discussions among cancer patients, HCPs, and community support providers. Reaffirming the results of Martin et al. [19], an overall low level of guideline knowledge among HCPs, a lack of education and resources, systemic challenges such as financial constraints, and the challenging variability of patients’ needs seem to complicate offering adequate services to patients. Gaps in patient–professional and interprofessional communication do appear to limit effective guideline implementation in CRF management further, although this was not considered in detail [18].

Thus, to improve our understanding of the interactional dynamics between HCPs and patients suffering from CRF and HCPs’ perceived roles in interprofessional CRF management, we conducted focus-group discussions with HCPs working in oncology. As this was lacking in previous studies, we intended to initiate a joint exchange and reflection on the topic between HCPs from different professions, taking into account the confusion among HCPs regarding role and communication challenges in CRF management [18]. Thereby, the aim was to develop suggestions first-hand and across multiple professions to improve the management of CRF, which may set the direction for future actions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study was a part of the Longitudinal Investigation of Cancer-Related Fatigue and its Treatment (LIFT) project. In accordance with a preceding, quantitative, cross-sectional survey among HCPs within the LIFT project [20–22], we chose a descriptive qualitative approach based on focus-group discussions to deepen insights into HCPs’ perspectives on the current management of CRF in Germany. Before the start of the focus-group discussions, participants provided informed consent and completed a questionnaire on sociodemographic and professional data. Ethics approval was granted by the institutional review board of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University (S-526/2018). The study was reported in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).

2.2. Participants

HCPs of three fields involved in cancer care, medicine, nursing, and psycho-oncology, were taken into consideration, enabling interprofessional exchange on the subject of CRF from a practical point of view. For each group, we aimed to recruit two representatives of the above-mentioned fields, respectively, resulting in a target size of six HCPs per group. Purposive and snowball sampling techniques were used in recruitment within the Departement of Internal Medicine II at the University Hospital Würzburg, Germany. Inclusion criteria were set as regular contact with cancer patients, i.e., seeing at least one cancer patient per week for the last year, as well as sufficient German skills. Depending on the HCPs’ availability, potential participants were either addressed personally during daily clinical practice or contacted via email.

2.3. Data Collection

Two focus-group discussions took place in May and June 2023 at the University Hospital Würzburg. A semistructured interview guide was developed based on the existing literature on CRF management and discussed within the research team. Guided questions were broad and addressed the personal experiences and needs of HCPs (e.g., “How do you experience your contact with cancer patients with CRF?”, “What challenges do you perceive in the everyday life of patients with CRF?”). The first author, who is experienced in qualitative research and conducting group discussions, moderated the focus-group discussions. A student assistant also trained in qualitative research took notes and surveilled recording.

At the beginning of each group discussion, the moderator gave an introduction on methodological aspects and encouraged participants to share their individual perspectives. This was followed by a round of personal introductions. Group discussion took 1.5 to 2 h, and an incentive of €25 was offered for participation. For further analysis, discussions were audio- and video-recorded and transcribed verbatim using Microsoft Word 365, and in the last step, names of particiapants and ward designations were removed from transcripts.

2.4. Analysis-Thematic Content Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed following the qualitative content analysis of Mayring [23]. Using the open-access web application QCAmap 2023 [24], the moderator and the student assistant coded the transcripts of both focus-group discussions independently. Content was categorized inductively following analysis questions formulated based on the topics covered in the focus groups, i.e., (1) HCPs’ experiences in handling patients with CRF, (2) perceived challenges in the everyday life of patients with CRF, (3) HCPs’ experiences in current CRF management, and (4) suggestions to improve CRF management. For any text component that covered meaningful content regarding one of the questions of analysis, a category was built. If a meaningful text component matched an already created category, it was assigned to this one. After categorization, separate for each analysis question, the category systems resulting from both coders were compared to each other. In accordance with Mayring [25], match rates as an approach to the intercoder reliability were estimated by the first project author (range: excellent, good, medium, and bad). In case of major discrepancies, categories were discussed between both coders until a consensus was achieved. Subsequently, thematic main categories were built inductively to bundle the number of categories. The quotations cited here were translated from German into English, discussed among the research team, and language-edited. Results on the third question of analysis are to be found solely in Supporting S4 for capacity reasons.

3. Results

The overall sample included four physicians (two male and two female), four psycho-oncologists (one male and three female), and three nurses (two male and one female). Detailed sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| M or n | SD or % | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 3 | 27.3% |

| 30–39 | 1 | 9.1% |

| 40–49 | 6 | 54.5% |

| 50–59 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 60–69 | 1 | 9.1% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 5 | 45.5% |

| Female | 6 | 54.5% |

| Work experience (years) | 13.9 | 7.5 |

| Work experience in oncology (years) | 10.2 | 6.3 |

| Leading position | ||

| Yes | 4 | 36.4% |

| No | 7 | 63.6% |

| Cancer patients per week | ||

| 2–5 | 2 | 18.2% |

| 6–10 | 1 | 9.1% |

| 11–20 | 3 | 27.3% |

| 21–30 | 2 | 18.2% |

| > 30 | 3 | 27.3% |

| Patients’ tumor entities | ||

| Breast | 5 | 45.5% |

| Colorectal | 5 | 45.5% |

| Prostate | 3 | 27.3% |

| Lung | 3 | 27.3% |

| Skin | 3 | 27.3% |

| Hematological | 8 | 72.7% |

| Othersa | 4 | 36.4% |

| Context of patient contact | ||

| Surgery | 3 | 27.3% |

| Radiation | 6 | 54.5% |

| System therapy | 10 | 90.9% |

| Pain therapy | 5 | 45.5% |

| Othersb | 3 | 27.3% |

| Patients’ treatment stage | ||

| During therapy decision | 8 | 72.7% |

| Acute therapy | 11 | 100.0% |

| Palliative therapy | 8 | 72.7% |

| Rehabilitation | 2 | 18.2% |

| Aftercare | 7 | 63.6% |

| Advanced training for oncology | ||

| Yes | 8 | 72.7% |

| No | 3 | 27.3% |

- Note: M, mean; n, number.

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

- aOther: Thyroid (n = 1), gynecological (n = 2), endocrinological (n = 1).

- bOther: Supportive care (n = 1), psycho-oncological counseling (n = 1), radioactive therapy (n = 1).

3.1. The Interaction Between HCPs and Patients With CRF

Figure 1 displays HCPs’ experiences in handling patients with CRF (left/blue part) and the challenges they perceived in the everyday life of patients (right/orange part) when interacting with each other. Regarding HCPs’ experiences in handling patients with CRF, 22 categories were extracted, which were subsumed under three main categories. The 20 categories identified as patients’ challenges were likewise subsumed under three main categories. Intercoder reliability for the first analysis question was estimated as good and for the second question as medium, according to Mayring [23]. The following results are supported by quotes. Further supporting quotes are available in Supporting S1-S2.

“Patients often present with symptoms of fatigue, sometimes with a medical history like this: ‘I’ve had it since I had cancer in 2008.’ Then I think, ‘Oh God, now they’re coming to me and I’m somehow supposed to give them new impulses.’” (Focus group 1 (FG1), physician)

They also partly noticed a more or less rigid bias on the patient side regarding the diagnosis of CRF itself and its treatability, as well as an ambivalence regarding symptom improvement that questions the efforts of HCPs.

“With cancer you have the diagnosis, you have the tumor, with fatigue there are different factors that play into it. But it’s not really tangible, neither for us nor for the patient.” (Focus group 2 (FG2), nurse)

“I believe that openness is also very, very important, to say, ‘We don’t have a patent remedy, we can look, we can see what suits you, but it is more of a long-distance run than a sprint.’” (FG2, psycho-oncologist)

“By pointing out […] that it is difficult, of course, but it is the continuation and the perseverance that counts. I think that is what you have to do.” (FG2, physician)

Even if HCPs considered it important to be there for patients and to listen to them, only some could value this as an actual competence. Others felt frustrated at the idea of just listening and not actively doing or offering anything.

Turning to the right side of Figure 1 (orange), HCPs named several perceived challenges in the everyday life of patients. Among these were practical challenges, such as impairment of daily life activities and/or impaired return to work. Dealing with CRF symptoms seemed to be complicated by their unpredictability. Moreover, changing family and friendship dynamics resulting from CRF seemed to affect the daily life of patients.

“It is often played down a bit, to be honest, because it is a sensitive and long process to take this medical history to be able to differentiate it.” (FG1, nurse)

“There are also many who, when they have a good day and are with me, are afraid and say, ‘Well, you don’t have to write it in the letter right now, because I’ll have the evaluation soon.’ […] They are so afraid that this could be a disadvantage, because they know ‘80% of the time is wasted and unfortunately I’m doing well today.’” (FG1, physician)

“[…] many forget that these are seriously ill people. Even if you don’t see it, they are seriously ill people.” (FG2, nurse)

“So, I think that many people really don′t anticipate what fatigue really means later in life. Yes, nor do we.” (FG2, psycho-oncologist)

3.2. Suggestions of HCPs on How to Improve CRF Management

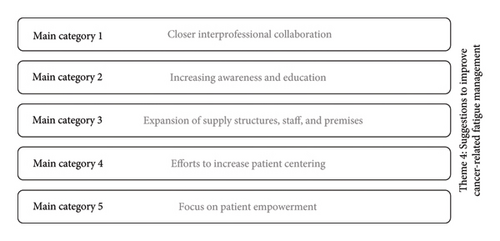

Participants’ suggestions as to how CRF management could be improved are presented in Figure 2. The final category system contained 27 categories, which were subsumed under five main categories. Intercoder reliability was estimated as good. Additional quotes are provided in Supporting S3.

“[…] you always have to think about what kind of communication culture I’m in right now and how I get that across without it seeming like I’m the smartass who knows better. Sometimes you have the feeling that you don’t want to ask someone because you think they should have thought of it, but maybe it’s not like that.” (FG1, physician)

“I would not dare to call the ward physician and say, ‘Here, could you record the iron value.’ I think to myself ‘He knows all that, he knows what to look for’.” (FG1, psycho-oncologist)

“[…] especially if no one is interested. When I tell the doctors, I don’t know what the doctors will do with it.” (FG1, nurse)

“I think it is important to create awareness in society as a whole, not only in hospitals, but also in families, among relatives, in professional life, so that it is more accepted.” (FG2, nurse)

“That’s the kind of overshooting. People who say, while the wound has not yet healed properly or there is still something undiscovered in the body, ‘Ah, he should be able to do more than on paper, he should be able to move, and if he were to move more, he would also feel better’.” (FG1, psycho-oncologist)

“‘The muscles work like a gland. If they do even a very little bit, messenger substances will come, which work particularly well against inflammation, which may in turn contribute to the fatigue. We can start with 10 minutes.’ Then, for them it is often like, ‘How can 10 minutes be enough when it says 150 everywhere?’” (FG1, physician)

“Evaluation and feedback on the progression of symptoms. That was what I was just talking about. The bottom line is that we can also learn from the patients what was helpful or what exactly made the difference so to speak.” (FG2, physician)

“[…] we need time and people and the idea givers, not only personnel in the sense of more, but also the right personnel. The people who are empathetic, who have the ideas, who guide someone, who give orientation. Everybody needs somebody to learn from […].” (FG2, physician)

“Fatigue is a symptom that makes you despair, but I think we don’t even do perfectly what we already know would be good. […] I always think to myself ‘Oh God, we should finally somehow manage to implement the standards in a coordinated manner, then it would certainly be better.’” (FG1, physician)

4. Discussion

We conducted two focus-group discussions involving physicians, nurses, and psycho-oncologists working in oncology to gain insights into the interactional challenges both between HCPs and patients, and between groups of HCPs in CRF management.

4.1. Awareness of the Challenges in the Everyday Life of Patients

Participants elaborated numerous challenges in the everyday life of patients. The presumptions of HCPs can be matched with patient perceptions from previous studies: patients reported CRF-related impairment of general activities, ability to work, and relationships with others, which we classified as practical challenges in patients’ everyday life, as well as impairment of mood and the ability to enjoy, which we classified among others as emotional challenges [2]. Perceptions of HCPs also seem to be equivalent to the experiences of patients regarding further emotional challenges such as feelings of dependency and helplessness [14]. Patients recently reported the feeling of being pressed or dismissed by HCPs [16, 18], as well as perceived overload resulting from the demanding treatment of CRF [13], feelings similar to the presumptions made by HCPs. Overall, HCPs seemed clearly to be aware of how challenging the everyday life of patients suffering from CRF might probably be.

4.2. Reflective Practice of HCPs for Empathetic Exchange

Despite their awareness of the demanding situation in which patients find themselves, HCPs in our study also admitted difficulties in dealing with CRF patients empathetically. On the one hand, there is the pressure of expectation from patients and their relatives, which is rather understandable due to the number of challenges in patients’ everyday lives. At the same time, HCPs are uncertain regarding CRF and its treatment, lack self-efficacy, or feel inadequate in CRF management [18–21]. These aspects paired with a general lack of time in healthcare, may impede HCPs’ recall of perceived challenges of patients in the moment of encounter. This may complicate dealing with patients empathetically or even impede HCPs to address CRF [16], which, in turn, may aggravate the feelings of inadequacy experienced by HCPs.

Thus, taking the patients’ perspective from time to time, as was initiated in the focus-group discussions, may contribute to a more empathetic and efficient approach to CRF [26]. HCPs in our focus groups valued the opportunity to take time to think about CRF and to exchange views with interprofessional colleagues as a result of study participation, given the lack of time for such interaction during the daily clinical routine. Reflection and exchange may not only favor HCPs’ empathy with patients suffering from CRF. As it transpired during group discussions, it may also foster their interprofessional collaboration by enhancing reciprocal empathy, as well as clarifying their personal responsibility [27].

4.3. The Lack of Clarified Roles and Leadership in Interprofessional CRF Management

Taking into account the multifactorial etiology and treatment of CRF, interprofessional collaboration among HCPs is necessary to meet the needs of patients and manage CRF efficiently. Hence, Nancarrow et al. [26] highlighted the role of leadership for the complex communication and coordination, as well as the clarity of roles regarding interprofessional collaboration in healthcare. According to our participants, both leadership and roles seem not to be clarified in CRF care, which complicates collaboration in their opinion. While physicians have a leading role within the interprofessional team in acute cancer therapy [14, 26], physicians in our, albeit monocentric, study tend not to see themselves in this role in CRF management due to an apparent lack of tangibility of CRF as a complaint.

4.4. Structural and Individual Contributions to Change

Overall, HCPs state that structural changes are needed to realize effective CRF management. This accompanies the call for changes in the healthcare system such as the allocation of staff and financial resources for CRF education [14]. At the same time however, participants highlight the necessity of a patient-centered attitude toward CRF among HCPs, as well as a willingness to collaborate within an interprofessional team. Even if this alone proves insufficient, structural changes in turn might fail to achieve improvement without according efforts on the individual level. With regard to the realization of interprofessional collaboration as a goal in CRF management, Schot et al. [28] emphasized HCPs’ substantiation to its realization calling it the “work to be able to work together” (p. 338).

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

With an overall small sample size of 11 participants from only one certified cancer center, the generalizability of our results to all oncological HCPs and to other cancer care settings is limited. Additionally, as participating HCPs, as well as the moderator and their assistant, were working within the same institution, previous interactions between the moderator and some of the participants were not completely avoidable. This was still considered acceptable, as the questions were addressed to the whole group of HCPs and contribution to the discussions was voluntary. Moreover, a possible selection bias toward a greater likelihood to participate in the study among interested HCPs being aware of CRF also needs to be taken into account. To reduce this bias, a financial incentive was offered for participation, which was, however, only taken up by less than half of the participants. Further, despite efforts to create a trustworthy atmosphere and to ensure participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views during group discussions, social desirability bias cannot be fully excluded. Thus, some participants could have withheld their opinion. In this context, it is sometimes recommended not to mix participants across authority and status lines [29]. In contrast, we rather consider the interprofessional constellation in our group discussions as a strength. To our knowledge, this is the first focus-group study taking into account the interprofessional challenges in CRF management from the perspectives of different professions, which reflects the daily clinical routine on the wards. In fact, at the end of the group discussions, participants across all three professions were very positive about the interprofessional exchange and declared that it should be conducted more often. Further, we aimed to reduce researcher bias by involving multiple researchers in the setup and conduct of the focus-group discussions, independent coding of the transcripts by two persons, and discussion of the results with peers. Finally, insights from the focus-group discussions are further limited by the lack of quantitative data. We do not claim for our study to provide an overall quantitative assessment of the patient–professional and interprofessional communication on CRF. However, the study reveals several challenges in the communication and management with respect to CRF and points out suggestions for improvement from the HCP perspective.

4.6. Implications for Practice and Research

To achieve interprofessional, patient-centered practice in CRF management, general interprofessional SOPs on CRF seem to be important to clarify the responsibility of each profession and give referral pathways to HCPs. Clear responsibilities will help to lower uncertainties and interprofessional communication barriers and by doing so save valuable time. However, freed-up time would instead be used in patient–professional communication; structures were needed to make conversation billable in healthcare. Therefore, health insurers and other relevant stakeholders of the healthcare system may need to be convinced of the benefits for patients and their relatives, but also of the (likely) cost-effectiveness of a good and appropriately funded CRF management, which can improve the physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning of patients in social and work life. Equivalently to such SOPs for HCPs, it is also necessary to guide patients through CRF management in an empowering manner using some form of routing slip timetabling upcoming steps in diagnostics. Empowerment may motivate patients to actively take part in patient–professional communication which in turn makes communication on CRF more effective for patients as well as for HCPs. With regard to the quality of care and HCPs’ self-efficacy, feedback cycles on patient outcomes in CRF treatment need to be implemented, e.g., by recording electronically the course of CRF over time and measures taken to deal with CRF. Moreover, the reflective practice of HCPs in the daily clinical routine should receive institutional support. Likewise, professional training on CRF and patient–professional communication regarding CRF need to be considered on the institutional level and realized accordingly. This should be followed by the expansion of multiprofessional services, including sociomedical services, or staff recruitment.

There are also desirable changes on the individual level for HCPs. HCPs are encouraged to cultivate reflective thoughts to increase empathy toward patients with CRF. Recalling the challenges in the everyday life of CRF patients and one’s own daily clinical routine may help HCPs to disclose. Even if difficult to endure, learning to listen to patients and to value their experiences as a first, but fundamental step in CRF management is also essential. Moreover, HCPs should break down CRF treatment recommendations in patient–professional communication to motivate patients and consequently try to see and value their patients’ steps forward. However, these changes on the individual level for HCPs should in turn be supported by the employer, e.g., through the provision of time for interprofessional discussions to enable the exchange of experiences.

Future research could follow up with conceptualizing the proposed communication skills training on CRF for HCPs from all the different professions and disciplines involved in cancer care. Our results from the focus-group discussions may be viewed as starting points in such a phase of conceptualization. Further on, communication skills training needs to be implemented and evaluated. While we assume the issues raised by HCPs in our study are even more pronounced in other, non-certified cancer care settings, this also needs to be clarified in future studies.

5. Conclusion

Considering CRF as a less tangible phenomenon, HCPs in our study emphasized interprofessional, patient-centered practice to meet patients’ needs and manage CRF effectively. However, there is an unfavorable interaction between CRF-associated challenges affecting both patients and HCPs. We extracted a large number of suggestions on how to improve current CRF management. Both efforts on the individual level of HCPs and structural changes in healthcare are necessary to facilitate interprofessional collaboration in CRF management and to treat patients with CRF appropriately.

Conflicts of Interest

Karen Steindorf, Martina E. Schmidt, and Imad Maatouk received funding for projects related to fatigue as institutional payment from the German Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF). Karen Steindorf received personal fees for lectures with some relation to fatigue. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was part of the LIFT project, which is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Grant Nos. MA 7865/3-1, SCHM 3423/3-1, STE 1493/6-1, project number 438839893).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the healthcare professionals from the Würzburg Comprehensive Cancer Center for participation and the teams on each ward for their support in recruitment, as well as Andrew Entwistle for language support.

Supporting Information

S1: Healthcare professionals’ experiences in handling patients with cancer-related fatigue. Category system containing (main) categories derived during qualitative content analysis regarding analysis question 1.

S2: Perceived challenges in the everyday life of patients with cancer-related fatigue. Category system containing (main) categories derived during qualitative content analysis regarding analysis question 2.

S3: Healthcare professionals’ suggestions for improvements in cancer-related fatigue management. Category system containing (main) categories derived during qualitative content analysis regarding analysis question 4.

S4: Healthcare professionals’ experiences in cancer-related fatigue management. Category system containing (main) categories derived during qualitative content analysis regarding analysis question 3.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of the study, i.e., the complete list of categories derived during qualitative content analysis, as well as supporting quotes from focus-group discussions, are provided as supporting information.