Drug-Induced Eyelid Edema: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Eyelid edema is a common clinical presentation with multiple etiologies, some of which can pose life-threatening risks to patients. Isolated eyelid edema, without additional significant signs or symptoms, presents a diagnostic challenge. A growing number of drugs are associated with the development of eyelid edema, particularly new-generation small molecules. To identify the most frequently implicated drugs in this clinical scenario, we conducted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria. Forty-three studies met the inclusion criteria, identifying the drug groups most frequently associated with isolated eyelid edema: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus), atypical antipsychotics (clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine), fillers (hyaluronic acid and polyalkylimide), and oncologic drugs (imatinib and pemetrexed). The epidemiological characteristics of the patients in each group were highly variable and reflected the use of the aforementioned drugs in heterogeneous populations. The response to eyelid edema treatments also varied significantly. Patients with eyelid edema induced by atypical antipsychotics showed the highest response to conservative therapy, with a 100 percent response following either dose reduction or drug discontinuation. On the other hand, the response to conservative treatments for eyelid edema caused by oncologic drugs was inconsistent, with cases of persistent edema even after drug cessation. In these cases, blepharoplasty proved to be an effective and long-lasting solution. Lastly, in most filler-induced cases, an excellent response was observed following treatment with intralesional hyaluronidase.

1. Introduction

Isolated eyelid edema, defined as swelling confined to one or both eyelids without accompanying systemic or ocular symptoms, represents a challenging clinical presentation. Although often benign and self-limited, it may occasionally be the sole manifestation of a drug-induced adverse reaction and should be promptly recognized to avoid unnecessary investigations or inappropriate treatments.

To date, systematic reviews specifically addressing isolated drug-induced eyelid edema are lacking. Previous nonsystematic reviews have categorized the broader causes of eyelid swelling—whether isolated or not—into infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, postsurgical, and iatrogenic categories [1, 2].

In routine clinical practice, common etiologies such as thyroid dysfunction [3], orbital cellulitis [4], or allergic contact dermatitis are usually prioritized in the differential diagnosis. However, when eyelid edema occurs in isolation and without signs of infection, inflammation, or systemic disease, the diagnostic process becomes considerably more complex.

Among iatrogenic causes, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are a well-known cause of angioedema involving the face, tongue, and eyelids [5].

However, eyelid involvement is infrequent and most often nonisolated. Beyond ACE inhibitors, a growing number of drugs—including new-generation targeted therapies—have been associated with isolated periorbital edema. For example, imatinib, a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), is known to induce periorbital edema in a substantial proportion of patients [6].

Similarly, other multikinase inhibitors appear to share this adverse effect, suggesting a potential class effect related to the inhibition of intracellular signaling pathways [7]. In this systematic review, we aimed to collect and analyze all published reports describing isolated eyelid edema attributed to pharmacologic agents, excluding cases of generalized angioedema or those associated with systemic findings. Our goal is to better characterize the clinical and pharmacological profiles of these rare but increasingly recognized adverse reactions, in order to raise awareness among clinicians and guide differential diagnosis and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

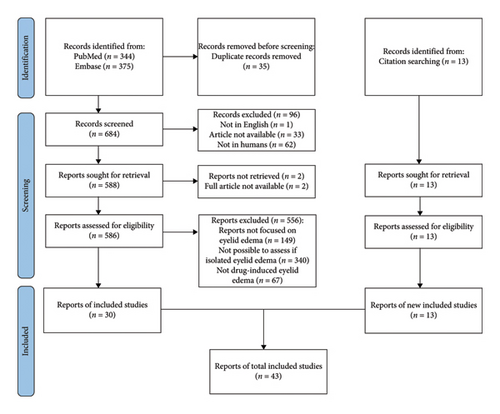

The study was designed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase databases were comprehensively searched without time limitations up to May 2022 to identify eligible articles. No specialized software was used in this process. To identify all relevant publications, the search terms included “periorbital,” “palpebral,” “eyelid,” “edema,” “swelling,” “drug-induced,” and “drug-related,” which were searched across all fields.

We also manually searched the references of included articles for any additional studies meeting the predefined inclusion criteria not identified in the initial searches.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All eligible case reports and case series worldwide were included. For this systematic review, inclusion criteria were patients with isolated eyelid or periorbital edema as an adverse drug effect (administered systemically or injected in the head and neck area).

After duplicate removal, articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts with the following criteria: (1) articles not focused on human patients, (2) articles not focused on eyelid edema, (3) articles not in English, and (4) abstracts or articles not available.

Articles remaining after the initial screening underwent a full-text review for inclusion. Subsequently, articles were excluded if they did not (1) focus on eyelid edema, (2) clearly state whether it was isolated, and (3) describe a clear etiological role of a specific drug in the onset of edema. Figure 1 shows the detailed search strategy.

2.3. Data Extraction

Four authors (I.T., J.T., L.G., and F.C.) independently evaluated the titles and abstracts from the aforementioned databases. For each selected study, we collected data on the first author, publication year, number of patients, patient’s age and sex, indication for treatment, drug causing eyelid edema, route of drug administration, time of onset of periorbital edema, clinical management, and outcomes.

3. Results

The initial database search yielded 344 and 375 items from PubMed and Embase, respectively (684 after duplicate removal). We excluded 96 studies that did not match the inclusion criteria based on the abstract review. After this exclusion, those deemed relevant (n = 586) were reviewed in full text and selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eventually, 43 studies were eligible for the final analysis.

In our study, we chose to include case reports and case series as the primary sources of information. This decision was made due to the limited availability of clear epidemiological data in other types of studies, where such information was often not clearly stated.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the patients (including age at diagnosis, sex, treatment indication, and route of the drug administration), clinical characteristics of edema (mono- or bilateral and time of onset from the start of therapy), clinical management, and outcome.

| Authors | Type of article | Year of publication | No patients | Age | Sex | Drug responsible | Route of drug administration | Cause of treatment | Time of onset | Bilateral or unilateral | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schear and Rodgers [8] | Case report | 2018 | 1 | 77 | F | Everolimus | Oral | Cardiac transplantation, carcinoid pulmonary mass | Onset of therapy | Bilateral |

|

|

| Pascual et al. [9] | Case report | 2005 | 1 | 40 | F | Everolimus | Oral | Polycystic kidney disease | 3 months | Bilateral | Dose reduction | Yes |

| Logan et al. [10] | Case series | 2017 | 2 | 58 | M | Sirolimus | Oral | Renal transplantation | Months | Bilateral |

|

|

| 43 | M | Sirolimus | Oral | Renal transplantation | 1 month | Bilateral |

|

No | ||||

| Mohaupt et al. [11] | Case series | 2001 | 5 | 16–71 | NA | Sirolimus | Oral | Renal transplantation | 1–5 months | Unilateral/Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes, persistent response |

| Gürbüz et al. [12] | Case report | 2020 | 1 | 19 | M | Clozapine | Oral | Schizophrenia | 2 years | Bilateral |

|

|

| Huttlin and Herrera [13] | Case report | 2020 | 1 | 23 | M | Clozapine | Oral | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 19 days | Bilateral |

|

|

| Visscher and Cohen [14] | Case report | 2011 | 1 | 49 | M | Clozapine | Oral | Schizophrenia | 6 years | Bilateral |

|

|

| Ayhan et al. [15] | Case report | 2017 | 1 | 15 | M | Olanzapine | Oral | Schizophrenia | 3 days | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes |

| Kuppili et al. [16] | Case report | 2018 | 1 | 45 | M | Olanzapine | Oral | Schizoaffective disorder | 2 months | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes |

| Malhotra and Shrivastava [17] | Case series | 2013 | 2 | 25 | M | Olanzapine | Oral | Schizophrenia | 7 months | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes |

| 16 | F | Olanzapine | Oral | Schizophrenia | 1 month | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes | ||||

| Zink et al. [18] | Case report | 2007 | 1 | 41 | M | Olanzapine | Oral | Psychosis | 1 day | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes |

| Bajaj et al. [19] | Case series | 2010 | 3 | 30 | F | Risperidone | Oral | Schizophrenia | 3 days | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes |

| 26 | F | Risperidone | Oral | Schizophrenia | 2 days | Bilateral |

|

|

||||

| 27 | F | Risperidone | Oral | Schizophrenia | 2 days | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes | ||||

| Pelizza [20] | Case report | 2008 | 1 | 39 | F | Risperidone | Oral | Schizophrenia | 14 days | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Yes, persistent response |

| Esmaeli et al. [21] | Case report | 2002 | 1 | 63 | M | Imatinib | Oral | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 month | Bilateral | Surgery (blepharoplasty) | Yes, persistent response |

| Larson et al. [22] | Case report | 2007 | 1 | 70 | M | Imatinib | Oral | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 weeks | Bilateral |

|

|

| Maalouf et al. [23] | Case report | 2004 | 1 | 76 | F | Imatinib | Oral | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 month | Bilateral | Surgery (blepharoplasty) | Yes, persistent response |

| Ramar et al. [24] | Case report | 2003 | 1 | 70 | M | Imatinib | Oral | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 2 weeks | Bilateral | 1st Tx: Low-salt diet, fluid intake restriction, topical corticosteroids | Partial response |

| McClelland et al. [25] | Case report | 2010 | 1 | 66 | M | Imatinib | Oral | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | Onset of therapy | Bilateral | Surgery (blepharoplasty) | Yes, persistent response |

| Mangla et al. [26] | Case report | 2015 | 1 | 77 | F | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 5th cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral |

|

|

| Martins-Filho et al. [27] | Case report | 2013 | 1 | 61 | F | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 5th cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral | Diuretics and dexamethasone | Yes, but recurrence after the readministration of the drug |

| Guhl et al. [28] | Case report | 2010 | 1 | 71 | M | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 1st cycle of chemotherapy | Unilateral | NA | NA |

| Kurata et al. [29] | Case report | 2006 | 1 | 56 | M | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 2nd cycle of chemotherapy | Unilateral |

|

|

| Badaoui and Mahé [30] | Case report | 2018 | 1 | 56 | M | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 3rd cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral | NA | NA |

| Schallier et al. [31] | Case series | 2010 | 2 | 70 | M | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 3rd cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral | NA | NA |

| 55 | F | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 4th cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral | Drug discontinuation | Partial response | ||||

| Munera-Campos et al. [32] | Case report | 2020 | 1 | 40 | F | Pemetrexed | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 2nd cycle of chemotherapy | Bilateral | Dexamethasone | Yes, but recurrence on readministration of the drug |

| Iverson and Patel [33] | Case report | 2017 | 1 | 72 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 12 months | Bilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response |

| Khalil et al. [34] | Case report | 2020 | 1 | 54 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 2 months | Bilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response |

| Teo et al. [35] | Case report | 2017 | 1 | 66 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | Years | Bilateral | Surgery (transconjunctival excision of nodules) | NA |

| Yu et al. [36] | Case report | 2017 | 1 | 54 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 24 months | Bilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response |

| Khan and Woodward [37] | Case report | 2015 | 1 | 42 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 72 months | Unilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response |

| Nathoo et al. [38] | Case series | 2014 | 2 | 43 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 23 months | Unilateral | NA | NA |

| 48 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 48 months | Unilateral | NA | NA | ||||

| Boger et al. [39] | Case report | 2019 | 1 | 68 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | NA | Bilateral | Surgery (excision of filler-associated tissue alterations) | NA |

| Dubinsky-Pertzov et al. [40] | Case series | 2021 | 17 | 54.9 (26–80years) | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 13.9 months (6–24 months) | Bilateral |

|

|

| Jordan and Stoica [41] | Case series | 2015 | 2 | 57 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 6–8 months | Bilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response |

| 44 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 12 months | Bilateral | Hyaluronidase | Yes, persistent response | ||||

| Wulu et al. [42] | Case report | 2019 | 1 | 48 | M | Silicone filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 12 months | Bilateral | Surgery (blepharoplasty) | Yes, persistent response |

| Vasquez et al. [43] | Case report | 2019 | 1 | 61 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | months | Bilateral |

|

|

| AlHarbi et al. [44] | Case series | 2019 | 16 | 40.3 (24–52years) | F | Polyalkylimide (Bio-Alcamid filler) | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 62.4 months (3–7 years) | Unilateral/Bilateral |

|

|

| Alsuhaibani and Alfawaz [45] | Case series | 2011 | 2 | 45 | F | Polyalkylimide (Bio-Alcamid filler) | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 45 months | Unilateral | Surgery (excision of filler-associated tissue alterations) | Yes |

| 32 | F | Polyalkylimide (Bio-Alcamid filler) | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 55.2 months | Unilateral | Surgery (excision of filler-associated tissue alterations) | Yes, persistent response | ||||

| Lin et al. [46] | Case report | 2021 | 1 | 52 | F | Hyaluronic acid filler | Intradermal | Aesthetic | 6 months | Bilateral |

|

|

| Ahmad and Steinhilber [47] | Case report | 2018 | 1 | 70 | F | Apixaban | Oral | Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation | 2 days | Bilateral | 1st Tx: Topical corticosteroids |

|

| Freyer and Mangan [48] | Case report | 2018 | 1 | NA | NA | Sorafenib | Oral | Acute myeloid leukemia | NA | Bilateral | Dose reduction | Yes, persistent response |

| Li et al. [49] | Case report | 2019 | 1 | 62 | F | Emactuzumab | Intravenous | Lung cancer | 2nd cycle of therapy | Bilateral |

|

|

| Tordjman et al. [50] | Case series | 1985 | 2 | 55 | F | Nifedipine | Oral | Unstable pectoral angina | 36 h | Bilateral | Dose reduction | Partial response |

| 58 | F | Nifedipine | Oral | Essential hypertension | NA | Bilateral | Dose reduction | Partial response | ||||

- Note: Tx: treatment.

- Abbreviation: NA, nonavailable.

Isolated eyelid edema was found to be associated with nine different drugs, which can be categorized into four groups. These include mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors such as sirolimus and everolimus; atypical antipsychotics including clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine; fillers such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and polyalkylimide; and oncologic drugs such as imatinib and pemetrexed. Additionally, we came across single reports of isolated eyelid edema associated with the drugs apixaban, sorafenib, emactuzumab, and nifedipine.

Nine cases of isolated edema were found for mTOR inhibitors. The mean age of onset was 54.5 years (range, 16–77 years); the M:F ratio was 1:1; however, it should be noted that the sex of the patients from the Mohaupt et al. case series was not clearly stated, as they did not provide explicit information regarding the gender of the five patients included in their study. The time of onset of the eyelid edema varied within a range of 0–5 months. Initially, conservative nonsurgical treatments, such as dose reduction or drug discontinuation, were attempted in all patients except one. Out of the eight patients who underwent this approach, seven (87.5%) achieved a complete response of the eyelid edema, although one of these patients experienced a recurrence of edema after readministration of the drug. For the ninth patient, attempts were made to address the edema through ablation using a radiofrequency probe, and although there was improvement following these treatments, the patient continued to have prominent soft edema on both eyelids. In the two cases where the conservative approach did not yield satisfactory results, the patients underwent surgery as a second-line treatment, resulting in a complete and persistent resolution of the eyelid edema.

Twelve cases of isolated eyelid edema were associated with atypical antipsychotics. The mean age of onset was 29.5 years (range, 15–49 years); the M:F ratio was 1.4:1 (seven male and five female patients). The mean time of onset exhibited significant variability (range, 0–72 months). All 12 patients had a complete response after conservative nonsurgical treatment, either dose reduction or drug discontinuation.

Five cases of isolated eyelid edema were associated with imatinib. The mean age of onset was 69 years (range, 63–76 years); the M:F ratio was 4:1 (four male and one female patient); the mean time of onset was 0.6 months (range, 0-1 month). Initially, a conservative nonsurgical treatment approach involving a low-salt diet, fluid intake restriction, and topical corticosteroids was attempted on two patients. However, since this approach was ineffective, all five patients eventually underwent surgery. Subsequently, four patients achieved a complete response, while one patient experienced a partial response.

Eight cases of isolated eyelid edema were associated with pemetrexed. The mean age of onset was 60.75 years (range, 40–77 years); the M:F ratio was 1:1 (four male and four female patients); the mean time of onset from the start of therapy was during the third cycle of chemotherapy (range, first to fifth cycle of chemotherapy). Among the eight patients, five were initially managed using conservative approaches, including the use of diphenhydramine, dexamethasone alone or in combination with diuretics, and drug discontinuation. However, none of these patients achieved a complete response to conservative treatment, and they experienced a recurrence of edema upon readministration of the medication. Treatment data were unavailable for three patients. Only one patient underwent second-line surgery, which resulted in a complete and sustained response.

Regarding fillers, 48 cases of isolated palpebral edema were found. The mean age of onset was 51.8 years (range, 26–80 years); the M:F ratio was 1:47 (l male and 47 female patients); the mean time of onset was 29.2 months (range, 2–72 months). A conservative nonsurgical approach using hyaluronidase was attempted on 24 patients. Among them, 19 patients showed a complete response, while five initially had a partial response but achieved a complete response after receiving a second treatment with hyaluronidase. In another group of 10 patients, a trial of removal of the filler material from the original site of injection by needling yielded no response, leading to surgery, which yielded favorable results. In six patients, surgery was performed as a first-line treatment: three achieved a complete response, two outcomes were not explicitly stated, and in one case, a partial response was observed, followed by a trial with hyaluronidase that resulted in a persistent response.

3.1. Bias and Quality Assessment

It is important to acknowledge that even if the level of certainty of evidence derived from case series or case reports is typically considered low, the inferences drawn from such reports can still offer valuable contributions to the decision-making process.

4. Discussion

Eyelid edema is a common clinical finding, often associated with other significant signs and symptoms. However, in cases where it occurs without other significant manifestations, it is referred to as isolated eyelid edema. Several drugs may be associated with isolated eyelid edema, emphasizing the importance of considering iatrogenic edema among the etiologies of this manifestation. To date, there have been no systematic reviews or meta-analyses dedicated to exploring this specific topic. In the following sections, we will describe the clinical features associated with drug-induced eyelid edema for the drugs we have found to be most commonly associated.

4.1. Sirolimus and Everolimus

In our systematic literature review, nine cases of isolated palpebral edema were associated with sirolimus and everolimus. Sirolimus, also known as rapamycin, belongs to a class of drugs that inhibit mTOR. Moreover, everolimus is a chemically modified form of sirolimus with improved bioavailability and reduced half-life. Initially approved for preventing acute rejection episodes in kidney transplantation, it has also gained approval for treating postmenopausal breast cancer, well-differentiated gastrointestinal or lung neuroendocrine tumors, giant cell subependymal astrocytoma associated with tuberous sclerosis, and metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [51, 52]. The most commonly reported adverse events of everolimus include anemia, nephrotoxicity, hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders, and increased susceptibility to infections [53, 54], which are similar to those reported for other immunosuppressive drugs.

Nonetheless, some patients may have atypical manifestations. These include arthralgia, hyperlipemia, lymphocele, and edema. Edema induced by mTOR inhibitors can take different clinical forms, such as lymphocele, angioedema, pleural and pericardial effusions, edema of the extremities and lymphedema, and finally, eyelid edema [55].

Although eyelid edema is among the possible adverse effects, only a few cases are reported. Mohaupt et al. published a case series of five patients experiencing significant eyelid edema caused by sirolimus [11].

Edema can be mono- or bilateral and is typically painless and nonpruritic. The development of noninflammatory eyelid edema tends to be gradual, progressing over several months [55].

The molecular mechanism underlying this manifestation is unknown. However, several hypotheses have been proposed. Sirolimus has been shown to increase prostacyclin production in rabbit endothelial cells [56]. Increased prostacyclin levels lead to vasodilation, resulting in fluid accumulation in the interstitial space. The alteration of lymphatic drainage is another pathophysiological mechanism [57]. Moreover, important effectors involved in lymphangiogenesis are regulated by the mTOR complex. Inhibition of mTOR leads to the reduced proliferation and migration of lymphatic endothelial cells driven by vascular endothelial growth factor-C [58]. Interestingly, although sirolimus and everolimus are hydrophobic macrocyclic lactones, similar to macrolides, eyelid edema is not frequently reported as an adverse effect in the latter drug group. This could potentially be related to the short course of antibiotic therapy compared with long-lasting immunosuppressive therapy or a specific molecular consequence of mTOR inhibition.

There are several possible management options for sirolimus- and everolimus-induced eyelid edema, including drug discontinuation, clinical observation, and surgical therapy. In most cases, the edema is mild and can be effectively managed with furosemide. In this case, drug discontinuation or dose reduction is not necessary. However, in severe cases where the edema is causing compromised visual function, discontinuing the drug and administering diuretics may not lead to improvement [10]. In such instances, surgical removal of the edematous eyelid has shown positive outcomes with stable results over time and without recurrence of edema even after drug readministration. Furthermore, drug discontinuation may not be a feasible option in some patients. Overall, the surgical approach is recommended for severe and persistent cases with visual field defects and significant skin redundancy, as it is associated with the most favorable risk-to-benefit ratio.

4.2. Imatinib

Imatinib is an oral signal transduction inhibitor that specifically targets protein tyrosine kinases, such as ABL, Arg (ABL-related gene), stem cell factor receptor (c-KIT), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R), and their oncogenic forms, most notably BCR-ABL [59]. It was the first protein kinase inhibitor to be clinically used in 2001 and is currently approved for treating CML and malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) [59, 60].

During imatinib therapy, adverse events may occur, including hematological side effects mostly consisting of cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) as well as nonhematologic events such as fluid retention, biochemical abnormalities, and gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders [61].

In our review, we identified five patients receiving imatinib therapy who developed eyelid edema as a side effect. Four patients had CML, and one had metastatic GIST. All patients developed bilateral eyelid edema within 1 month of starting therapy, suggesting that imatinib-induced eyelid edema seems to be an early adverse reaction.

The precise mechanism for imatinib-induced periorbital edema is not yet fully understood, but several hypotheses have been proposed. The most widely accepted theory involves the inhibition of PDGF-R signaling [25]. Histopathological findings have revealed that dermal dendrocytes, which are abundant in periocular skin, express PDGF-R [6]. Furthermore, PDGF-R signaling cascade inhibition by imatinib may result in increased capillary permeability and fluid extravasation, leading to localized edema. Another hypothesis suggests that the unique anatomical characteristics of the orbit, characterized by a dense collagenous orbital septum and poorly developed lymphatic system, predispose this region to edema [6].

Among the available treatment options, surgery has proven to be the most effective in resolving the edema in all reported cases, while conservative management only achieved a partial response.

4.3. Pemetrexed

Pemetrexed is a multitargeted antifolate drug that inhibits enzymes involved in folate metabolism and DNA synthesis. It is commonly used in the treatment of non–small-cell lung carcinoma and mesothelioma [62]. Although generally well tolerated, pemetrexed has a broad spectrum of adverse reactions, ranging from mild to moderate adverse reactions, such as fatigue, mucositis, and skin rashes, to severe adverse reactions, such as renal failure, neutropenia, anaphylactic shock, and toxic epidermal necrolysis [63].

Although rare, isolated periorbital edema has been described among the adverse reactions related to pemetrexed [30]. A study conducted by Eguia et al. in 2011, involving 107 patients treated with pemetrexed, reported periorbital edema in 15% (16/107) [64]. So far, eight cases of pemetrexed-induced isolated eyelid edema have been documented. Most patients experienced bilateral periorbital edema, but unilateral edema was also reported. The time elapsed between the first drug administration and the onset of edema varied widely, ranging from the first to the fifth cycles of chemotherapy.

The exact mechanisms underlying pemetrexed-induced eyelid edema remain unclear. One theory suggests that soft tissue swelling and the accumulation of noncancerous fluid in the eyelids, similar to the effects observed with agents such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (such as imatinib and nilotinib) and mTOR inhibitors (such as sirolimus), may be attributed to the leakage of proteins from capillaries [30].

Treatment options include conservative measures such as systemic corticosteroids and diuretics, which can lead to partial improvement of the edema. However, it has been observed that the edema tends to recur upon readministration of pemetrexed. In most cases, antineoplastic therapy discontinuation was not a feasible option [65], but in some rare cases, when the benefit-risk balance allows for it, discontinuation of pemetrexed therapy has been attempted, leading to a partial improvement of the eyelid edema.

In some cases, surgical intervention such as blepharoplasty has shown to be effective in achieving complete and lasting resolution of the edema [10]. However, it should be noted that the long-term efficacy of these treatments for eyelid edema in the context of advanced non–small-cell lung carcinoma is not well documented, given the poor prognosis associated with the disease. Nevertheless, considering the benefit-risk ratio, blepharoplasty may be a reasonable choice for managing pemetrexed-induced eyelid edema.

4.4. Olanzapine, Clozapine, and Risperidone

Atypical antipsychotics may be a cause of isolated eyelid edema and must be included in the differential diagnosis. Twelve cases of isolated eyelid edema associated with olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone have been reported in the literature.

Olanzapine is commonly used for the management of both negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia [66]. Several adverse effects are described, including numerous cases of peripheral edema [67]. In our systematic review of the literature, five cases of isolated eyelid edema related to olanzapine were reported. The period between the start of therapy and the onset of edema varied widely, ranging from 1 day to 7 months. Interestingly, all reported patients responded to drug discontinuation. Similarly, three casesof isolated eyelid edema were associated with clozapine, which is used as a second-line drug in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. The time interval between the first drug administration and the onset of edema was longer than olanzapine (between 19 days and 6 years). All patients responded to drug discontinuation, but systemic steroids, antibiotics, and antihistamines were ineffective. In one case, the edema recurred after drug readministration, postoperatively. Risperidone is a benzisoxazole antipsychotic drug, and its activity is mediated through a combination of D2 and 5-HT2 receptor antagonism. Four cases of risperidone-induced periorbital edema have been reported. The time interval between the start of risperidone use and the onset of edema was shorter than olanzapine and clozapine, ranging from 2 to 19 days. Similar to other atypical antipsychotics, eyelid edema completely resolved after the drug discontinuation.

The exact mechanism underlying eyelid edema induced by atypical antipsychotics is unknown, but renal D4 receptor inhibition may lead to reduced natriuresis and, therefore, eyelid edema. Other hypotheses include vasodilation induced by blockade of the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors and stimulation of muscarinic, serotonergic, and adrenergic receptors [16].

4.5. HA Filler

In our review, we identified several cases of isolated eyelid edema following soft tissue filler injections, mostly HA, but also including nonresorbable agents such as polyalkylimide. The majority of affected patients were middle-aged women, who underwent the procedure for esthetic reasons. HA fillers are among the most commonly used materials for periorbital rejuvenation, offering temporary and reversible esthetic enhancement with an acceptable safety profile. Nevertheless, periorbital edema is a recognized adverse effect, which may appear acutely or manifest with a significant delay [37]. Delayed periorbital edema typically occurs months to years after the procedure—on average 27.1 months in reported cases—and is often associated with persistent filler material within the eyelid tissues [38]. In the case of HA, its cross-linked structure contributes to prolonged tissue retention and fluid attraction, while in the case of polyalkylimide, the material may migrate from distant facial regions and provoke a granulomatous reaction or space-occupying effect. Both mechanisms can ultimately result in lower eyelid swelling, even in the absence of recent injections or inflammatory signs.

The pathophysiology of this phenomenon remains incompletely understood. Hypersensitivity to filler components has been proposed but is considered unlikely in the absence of overt inflammation. Several authors have suggested that fillers may exacerbate pre-existing anatomical predispositions to fluid retention by impairing lymphatic or venous drainage in the periorbital region [36, 68]. Moreover, delayed edema may be due to reactions to cross-linkage breakdown products [69], or by chronic low-grade inflammation and tissue remodeling around the filler [70].

A recent review by Eshraghi et al. highlighted key diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in patients presenting with late-onset periorbital edema after HA injection, emphasizing the value of ultrasound and the efficacy of hyaluronidase in cases of suspected retained filler [70].

When isolated eyelid edema is observed in patients with a history of facial filler injection, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion, even if the procedure was performed years earlier. In cases related to HA, intralesional hyaluronidase represents the treatment of choice and may require repeated sessions to achieve complete resolution [36]. In contrast, excision may be necessary for persistent or granulomatous lesions, particularly those related to permanent fillers such as polyalkylimide. Blepharoplasty can be considered in refractory cases.

4.6. Other Drugs

Isolated eyelid edema has been sporadically associated with other drugs, including apixaban [47], sorafenib [48], emactuzumab [49], and nifedipine [50]. However, limited data are available regarding the specific relationship between these drugs and eyelid edema.

5. Conclusion

Isolated eyelid edema without additional significant signs or symptoms presents a diagnostic challenge, and its occurrence as a result of medication use has been associated with different drug groups. However, data remain limited regarding the specific relationship between these drugs and eyelid edema. Further research is needed to gain a better understanding of the potential mechanisms and risk factors associated with drug-induced eyelid edema caused by these medications.

Through our research, we aimed to contribute to the body of knowledge regarding drug-induced eyelid edema, offering insights into potential causal agents beyond the well-established associations. By expanding the understanding of drug-induced edema, we can enhance patient safety, improve diagnostic accuracy, and facilitate appropriate management strategies for this condition.

6. Limitations of the Study

This review is based primarily on published case reports and case series, which, while appropriate for investigating rare phenomena, are inherently subject to selective reporting and do not allow for formal bias assessment or meta-analysis. Furthermore, relevant cases may be present in pharmacovigilance databases (e.g., FAERS and EudraVigilance) or unpublished early-phase trials, which were not included in our search strategy. As a result, the true frequency and spectrum of drug-induced isolated eyelid edema may be broader than what is currently described in the literature. Finally, the suggested therapeutic approaches—particularly surgical options such as blepharoplasty or excision of lymphedematous tissue—are based exclusively on case and should therefore be interpreted with caution until more robust evidence becomes available.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review of literature as it involved the analysis of previously published studies that were publicly available. The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and followed established ethical principles.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

J. Tartaglia and I. Tudurachi contributed equally to the paper. J. Tartaglia and I. Tudurachi share first authorship and should be marked as co-first authors.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.