A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) Investigating the Efficacy and Safety of Acupuncture in Treating Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion (I/R) Injury

Abstract

Objectives: This study systematically reviewed and meta-analyzed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy and safety of acupuncture in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database, and Wanfang from database inception to November 3, 2024. Eligible RCTs assessing acupuncture for myocardial I/R injury were included. Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 16.

Results: A total of 26 RCTs of moderate methodological quality were included. Acupuncture significantly reduced myocardial enzyme levels compared to controls. Inflammatory markers (hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1) were suppressed, while anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory factors (IL-10 and IL-2) increased. Oxidative stress parameters showed improvements, with reductions in MDA and SOD levels. Echocardiographic findings demonstrated enhanced cardiac function, reflected by increased LVEF and LVESV, along with reductions in LVFS, LVEDD, LVEDV, and LVESD. Additionally, acupuncture alleviated TCM chest pain symptoms, shortened ICU stays, lowered MACE incidence, and improved 6MWT and SAQ indicators. No adverse reactions were reported.

Conclusion: Acupuncture attenuates myocardial injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress while activating anti-inflammatory and immune responses, enhancing cardiac function, and mitigating ventricular remodeling. Furthermore, it alleviates chest pain, shortens ICU stays, reduces adverse cardiovascular events, and improves 6MWT and SAQ indicators.

1. Introduction

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury is a prevalent clinical cardiovascular disorder. Following a period of ischemic myocardial blood supply interruption, subsequent restoration of perfusion does not effectively repair the damaged tissue but instead exacerbates myocardial injury, inducing further lesions and necrosis [1]. The resulting damage spans various critical functions, including cardiac pump efficiency, electrophysiological stability, myocardial fiber ultrastructure, and energy metabolism, ultimately leading to irreversible cardiomyocyte apoptosis, enhanced necrosis, and infarct expansion [2, 3]. Myocardial I/R injury frequently precipitates complications such as cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, and other adverse cardiovascular events, posing significant risks to patient survival and health [4]. It is commonly associated with procedures such as coronary angioplasty, thrombolytic therapy for myocardial infarction, and cardiac surgery [5]. The injury occurs in two distinct phases: initial coronary artery occlusion leads to a dramatic reduction in myocardial perfusion, inducing ischemia that triggers apoptosis and necrosis, ultimately resulting in myocardial cell death. In contrast, reperfusion, which involves the sudden influx of blood into the ischemic tissue, further exacerbates the condition by inducing oxidative stress, calcium (Ca2+) overload, and inflammation. These processes promote cardiomyocyte apoptosis and intensify damage to ischemic myocardial tissue, complicating the management of ischemic cardiomyopathy, worsening the patient’s condition, and ultimately affecting the prognosis [6]. The global incidence of cardiovascular disease continues to rise, establishing it as the leading cause of death worldwide [7]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the primary cause of mortality and disability globally. In 2019, IHD affected 197 million people, resulting in 9.14 million deaths, which accounted for 16% of global mortality [8]. Deaths from acute myocardial infarction have increased by 22.3% over the past decade, imposing a substantial health and economic burden on society [9]. Despite advancements in early vascular recanalization technologies, the secondary myocardial injury induced by reperfusion significantly impacts the prognosis of myocardial infarction patients. Clinical and laboratory studies [10, 11] have demonstrated that myocardial I/R injury heightens the risk of severe cardiovascular events, including heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, renal failure, in-stent restenosis, cerebrovascular accidents, and mortality. Targeting the molecular pathways associated with myocardial I/R injury offers a promising approach to reducing the incidence of such adverse outcomes.

Modern therapeutic approaches for myocardial I/R injury primarily encompass physical and pharmacological interventions, both of which have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy in clinical and preclinical studies [3, 12–15]. However, physical therapies—including postischemic conditioning, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, hypothermia therapy, remote ischemic conditioning, and exercise training—face significant limitations related to ethical concerns, environmental constraints, feasibility of widespread application, and insufficient high-quality evidence from large-scale clinical trials. Pharmacological treatments remain largely confined to the preclinical stage, with many compounds exhibiting promising effects only in animal models. Moreover, the adverse effects associated with certain drugs substantially restrict their clinical utility. As a result, the development of a safe and effective treatment for myocardial I/R injury remains a significant challenge. Acupuncture, a fundamental therapeutic modality in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which involves the precise stimulation of acupoints using specialized instruments, combined with manipulation techniques intrinsic to TCM. In recent years, acupuncture has gained attention as a safe, cost-effective, and promising nonpharmacological intervention for cardiovascular diseases, including angina pectoris [16], hypertension [17], and arrhythmia [18]. Between 2000 and 2020, 2471 systematic reviews on acupuncture were published in the Science Network database, of which 235 (9.5%) focused on cardiovascular diseases [19]. Clinically, electroacupuncture at Neiguan (PC6), Lieque (LU7), and Yunmen (LU2) has shown to reduce serum cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels, enhance muscle strength scores, and shorten intensive care unit (ICU) stays in adult patients undergoing cardiac valve replacement, thereby mitigating myocardial I/R injury [20]. Additionally, transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation at bilateral Neiguan (PC6) has been reported to significantly lower serum cTnI and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery, effectively reducing myocardial damage [21]. Despite these promising findings, no comprehensive evidence-based evaluation has been conducted to objectively assess the clinical efficacy and safety of acupuncture in the management of myocardial I/R injury. To address this gap, the present study performs a meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating acupuncture for myocardial I/R injury, providing a reference for the design and implementation of future clinical research in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [22] and the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) guidelines [23].

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria of the Research Literature

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria of the Research Literature

- 1.

Study Design: This includes RCTs evaluating acupuncture for myocardial I/R injury.

- 2.

Participants: It includes patients diagnosed with myocardial I/R injury, including those undergoing coronary angioplasty, thrombolytic therapy for myocardial infarction, or cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, irrespective of age, sex, nationality, or ethnicity.

- 3.

Interventions: The experimental group received acupuncture-based treatments, including electroacupuncture, transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation, auricular therapy, or acupuncture in combination with other interventions. The control group underwent sham acupuncture, standard pharmacotherapy, or nonacupuncture-related treatments. If the experimental group received acupuncture alongside other therapies, the control group was required to follow an identical treatment regimen, excluding acupuncture.

- 4.

Treatment Timing: Acupuncture was administered either pre- or postanesthesia induction.

- 5.

Treatment Parameters: No restrictions were imposed on treatment duration, stimulation intensity, or acupoint selection.

- 6.

Outcome Measures: This includes the following:

- a.

Serum myocardial enzyme levels: These levels include cTnI, creatine kinase-myoglobin binding force (CK-MB), creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

- b.

Inflammatory markers: These include high sensitivity (hs)-CRP, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-6, IL-2, and IL-1.

- c.

Oxidative stress indicators: These include malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD).

- d.

Echocardiographic parameters: These include left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular shortening rate (LVFS), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD).

- e.

Cardiac functional recovery: This includes heartbeat recovery rate.

- f.

TCM symptom score: This score includes chest pain severity assessment. Studies were included if they reported at least one of the above outcome measures.

- a.

- 7.

Language Restrictions: Only studies published in Chinese or English were considered.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria of the Research Literature

- 1.

Study Type: Semi-RCTs, randomized crossover trials, case reports, research protocols, animal studies, theoretical discussion, expert reviews, or systematic reviews were excluded.

- 2.

Interventions: Studies unrelated to acupuncture or those comparing different acupuncture modalities without a control group were not included.

- 3.

Participants: Studies that did not involve myocardial I/R injury patients or that assessed unrelated biomarkers were excluded.

- 4.

Duplicate Publications: Repeated studies were omitted.

- 5.

Data Integrity: Articles with incomplete data, significant statistical errors, or methodological flaws that compromised the validity of conclusions were excluded.

2.2. Data Retrieval

Computerized searches were conducted across the following databases from inception to November 3, 2024: PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database, and China Science and Technology Journal Database (VIP). Additionally, reference lists of included studies were screened to identify the supplementary relevant literature. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary with free-text terms. Chinese search terms included (“针灸” OR “针刺” OR “艾灸” OR “电针” OR “毫针” OR “头针” OR “皮内针” OR “经皮穴位电刺激” OR “耳穴” OR “温针灸”) AND (“心肌缺血再灌注损伤” OR “心肌缺血再灌注” OR “心脏置换” OR “心脏溶栓” OR “PCI术后” OR “心肌I/R” OR “心脏手术” OR “经皮冠脉介入” OR “心脏支架” OR “MIRI”). English search terms included (“Electroacupuncture” OR “Acupuncture” OR “Moxibustion” OR “Auricular acupuncture” OR “Acupoint” OR “Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation” OR “TEAS”) AND (“MI/R injury” OR “MIRI” OR “Myocardial I/R” OR “Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury” OR “Myocardial reperfusion injury” OR “Cardiac replacement” OR “Cardiac thrombolysis” OR “PCI” OR “Heart surgery” OR “Percutaneous coronary intervention” OR “Cardiac stent”). Furthermore, the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry and ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) were queried to identify ongoing or recently completed studies. The specific search strategy for PubMed is detailed in Table 1.

| Number of the formula | Combination of search terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | Electroacupuncture’: ab,ti OR ‘acupuncture’: ab,ti OR ‘moxibustion’: ab,ti OR ‘auricular acupuncture’: ab,ti OR ‘acupoint’: ab,ti OR ‘transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation’: ab,ti OR ‘teas’: ab,ti |

| #2 | Mi/r injury’: ab,ti OR ‘miri’: ab,ti OR ‘myocardial i/r’: ab,ti OR ‘myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury’: ab,ti OR ‘myocardial reperfusion injury’: ab,ti OR ‘cardiac replacement’: ab,ti OR ‘cardiac thrombolysis’: ab,ti OR ‘pci’: ab,ti OR ‘heart surgery’: ab,ti OR ‘percutaneous coronary intervention’: ab,ti OR ‘cardiac stent’: ab,ti |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 |

2.3. Outcome Assessment Indicators

Primary outcome measures included the following: (1) serum myocardial enzyme levels (cTnI, CK-MB, CK, AST, and LDH); (2) serum inflammatory markers (hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, IL-2, and IL-1); (3) serum oxidative stress markers (MDA and SOD); (4) echocardiographic parameters (LVEF, LVFS, LVEDD, LVEDV, LVESV, and LVESD); (5) heartbeat recovery rate; and (6) TCM chest pain symptom score. Secondary outcomes comprised the following: (1) ICU length of stay, (2) total hospital length of stay, and (3) incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

2.4. Literature Screening and Data Extraction

Two researchers independently screened the literature, extracted data, and conducted cross-verification based on the specified criteria. Literature selection was managed using EndNote X9. The initial screening involved reviewing titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant studies, followed by a full-text assessment to determine eligibility. Extracted data were systematically tabulated, including study title, author, sample size, patient age, intervention details, intervention timing, and all reported outcomes. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with arbitration by a third researcher if needed.

2.5. Risk Bias and Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using Review Manager 5.3, following the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias framework, which evaluates seven domains: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), completeness of outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias), and other potential sources of bias. Two reviewers independently rated each study as having a low, unclear, or high risk of bias and cross-checked the results. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer consulted if necessary. Additionally, the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) was used to evaluate the quality of evidence.

2.6. Statistical Treatment

To obtain original data for graphical results, the corresponding author was initially contacted. If data remained unavailable, Web Plot Digitizer was used to extract Mean ± SD values from images. RevMan 5.3 and Stata 16 were employed for statistical analysis, including meta-analysis and effect size estimation. Meta-analysis results were presented via pairwise comparison of tables and forest plots. For single-target indicators, results were also reported based on normative effects. For continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) was used to calculate effect sizes, while the standardized mean difference (SMD) was applied to mitigate heterogeneity due to variations in measurement units and methods. For categorical data, the relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed. A heterogeneity threshold of p = 0.1 was set, with p < 0.1 indicating significant heterogeneity. The I2 statistic was used for quantitative heterogeneity assessment, with I2 > 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. In such cases, a random effects model (REM) was applied; otherwise, a fixed effects model (FEM) was used. When significant heterogeneity was detected, a subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis was conducted based on the timing of outcome measurement to identify potential sources of variation. Publication bias was assessed for outcome indicators with more than 10 studies using funnel plots. The Egger test was performed to detect publication bias, with p < 0.1 considered statistically significant. If substantial heterogeneity persisted, descriptive analysis was conducted, and sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Screening Process and Results

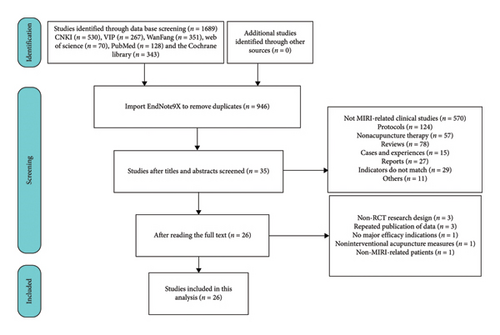

A total of 1689 relevant studies were retrieved, including 530 from CNKI, 267 from VIP, 351 from Wanfang, 70 from Web of Science, 128 from PubMed, and 343 from the Cochrane Library. Studies were screened based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, yielding 946 unique records after removing duplicates. Following title and abstract screening, exclusions included 391 animal studies, 179 unrelated to nonmyocardial I/R injury, 121 Cochrane Library registers, three study protocols, 57 nonacupuncture studies, 78 reviews, 15 case reports, 11 news reports, four announcements, one advertisement, 11 clinical study reports, and 29 clinical observations. Additional exclusions comprised five theoretical discussion, two letters, two editorials, one questionnaire survey, and one clinical application guideline. Full-text analysis of 35 shortlisted articles led to the exclusion of three non-RCT designs, three duplicate data publications, one study lacking key efficacy indicators for myocardial I/R injury, one unrelated to acupuncture treatment, and one involving nonpatient subjects. Ultimately, 26 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis [20, 21, 24–47]. Representative exclusions included a study [16] demonstrating that acupuncture significantly reduced angina frequency and severity while improving 6-min walk test (6MWT) performance. However, its inclusion of coronary heart disease or stent-implantation patients, along with discrepancies in reported indicators, rendered it ineligible. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

3.2. Basic Characteristics and Overview of Included Studies

Twenty-six RCTs conducted between 1999 and the present have enrolled a total of 1948 patients, aged 2–80 years, undergoing cardiac surgery. Among them, 970 patients in the intervention group received acupuncture, electroacupuncture, or transcutaneous electrical stimulation at acupuncture points, while 978 in the control group underwent sham acupuncture, sham electroacupuncture, sham transcutaneous electrical stimulation, or no intervention. Baseline characteristics were comparable across all studies. Notably, all trials were conducted in China, with four published in English-language databases and 22 in Chinese databases. Table 2 provides a detailed summary of study characteristics.

| Serial number | Author | Year | Number of cases | Sex (male/female) | Age (years) | Surgical procedure | Intervention | Selection of acupuncture points | Outcome indicator | Follow-up duration | Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test group | Control group | Acupuncture group | Control group | ||||||||||

| 1 | Yang et al. [20] | 2010 | 30 | 30 | 27/33 | 47–51 | Heart valve replacement surgery | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, 5 times, once each day, 30 min each time | Sham electroacupuncture | Neiguan (PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | ICU mechanical ventilation time, length of stay in the ICU, total blood transfusion, total chest drainage, muscle strength score (1, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h), cTnI (1, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h) | Not mentioned | Shaanxi, China |

| 2 | Dai [24] | 2019 | 30 | 30 | 36/24 | 56–80 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Electroacupuncture, 6 sessions, 3 days preoperatively and 3 days postoperatively, 1 session per day, 30 min each session | None | Neiguan (PC6); Zusanli (ST36); Guanyuan (RN4) | TCM chest pain symptom score, CK-MB (24 and 48 h), cTnI (24 and 48 h), CRP (24 and 48 h), microalbuminuria creatinine ratio (MACE) status (30 days) | 30 days | Sichuan, China |

| 3 | Shan et al. [25] | 2010 | 15 | 15 | 15/15 | 30–60 | Extracorporeal circulation for the repair of atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, mitral valve replacement, and pulmonary sternotomy | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, once, 30 min | None | Neiguan (PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | TNF-α (2 and 24 h), IL-2 (2 and 24 h), IL-10 (2 and 24 h) | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 4 | Zhu et al. [26] | 2023 | 28 | 29 | 34/23 | 18–74 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, once, 30 min | None | Neiguan (PC6); Daling (PC7) | cTnI (24 h), CK (24 h), CK-MB (24 h), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) mRNA (24 h), myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) mRNA (24 h), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) mRNA (24 h) | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 5 | Liang et al. [27] | 2021 | 43 | 43 | 47/39 | 18–70 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture, 14 times, once each day, 30 min each time | None | Neiguan (PC6); Gongsun (SP4); Danzhong (CV17); Xuehai (SP10); Zusanli (ST36); Sanyinjiao (SP6) | CK, AST, LDH, CK-MB, LVEDD, LVESD, LVEF, the Rhode Island methods to improve diagnostic assessment and services (MIDAS) scale, TCM chest pain symptom score, clinical efficacy index | Not mentioned | Beijing, China |

| 6 | Xiao et al. [28] | 2018 | 20 | 20 | 17/23 | 18–55 | Extracorporeal cardiac surgery | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, 20 min preoperatively to end of the procedure | None | Neiguan (PC6); Ximen (PC4); Shenmen (HT6); Baihui (GV20) | hFABP (0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 24 h), cTnI (0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 24 h) and MDA concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 24 h), myocardial contractility score (1, 6, and 24 h), arrhythmia score (24 h) | Not mentioned | Guizhou, China |

| 7 | Wang [29] | 2019 | 30 | 30 | 40/20 | 28–64 | Heart valve replacement surgery | Electroacupuncture pretreatment, 30 min | Sham electroacupuncture | Baihui (GV20); Yintang (EX-HN3); Shuigou (DU 26) | TNF-α (0, 6, 24, and 72 h), IL-6 (0, 6, 24, and 72 h), IL-10 (0, 6, 24, and 72 h), NSE (0, 6, 24, and 72 h), S100β (0, 6, 24, and 72 h), CAM-ICU scale (3 days), qoR-40 scale (3 days), incidence of POD (3 days), duration of ICU stay, and duration of hospital stay | Not mentioned | Anhui, China |

| 8 | Ma et al. [30] | 2015 | 25 | 25 | 12/38 | 36–63 | Heart valve replacement surgery | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, 30 min preoperatively to end of the procedure | None | Neiguan (PC6) | MDA (0.5, 6, and 24 h), SOD (0.5, 6, and 24 h), cTnI (0.5, 6, and 24 h), heartbeat recovery rate, dopamine dosage, epinephrine dosage, and nitroglycerin dosage | Not mentioned | Shandong, China |

| 9 | Wang et al. [31] | 2022 | 100 | 100 | 128/72 | 65–76 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture, 14 times, once per day, 30 min | Sham acupuncture | Neiguan (PC6); Shenmen (HT6); Zusanli (ST36) | Incidence of heart failure, IL-1, TNF-α, BNP, LVEF | Not mentioned | Fujian, China |

| 10 | Wang et al. [32] | 1999 | 12 | 16 | NA | 26–38 | Extracorporeal cardiac surgery | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, once, 20–30 min | None | Neiguan (PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | MAP, SpO2, dopamine dosage, sodium nitroprusside dosage, complication rate, heartbeat recovery rate | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 11 | Wang et al. [33] | 2000 | 10 | 9 | 9/12 | 26–35 | Atrial septal defect repair | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, once, 20–30 min | None | Neiguan (PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | SOD, MDA, CK-MB, mean arterial pressure, heart rate | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 12 | Zhang [34] | 2020 | 30 | 30 | 33/27 | 35–75 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture, 5 times a week for 1 month | None | Lieque (LU7); hHegu (LI4); Shenmen (HT6); Neiguan (PC6); Quchi (LI11); Chize (LU5) | TCM chest pain symptom score, SF-36 score, hs-CRP, IL-6, TC, TG, LDL-C, ECG changes | Not mentioned | Guangxi, China |

| 13 | Zhao et al. [35] | 2021 | 47 | 47 | 49/45 | 65–75 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of acupuncture points, 30 min preoperatively to the end of the procedure | Sham transcutaneous electrical stimulation at acupuncture points | Neiguan (PC); ximen (PC4) | ET-1 (8 and 21 h), vWF (8 and 21 h), NO (8 and 21 h), FMD (8 and 21 h), IL-6 (8 and 21 h), IL-10 (8 and 21 h), MMP-9 (8 and 21 h), hs-CRP (8 and 21 h) | Not mentioned | Hebei, China |

| 14 | Chi et al. [36] | 2014 | 80 | 80 | 70/90 | 51–71 | Heart valve replacement surgery | Electroacupuncture preconditioning, once, 20–30 min | None | Zhongfu (LU1); Chize (LU5); Ximen (PC4) | Surgical success rate, anesthetic drug dosage, duration of surgery, duration of aortic block, heartbeat recovery rate, postoperative blood loss, drainage volume, pulmonary infection, vocal cord injury, time to first mobilization from bed, time to first postoperative meal, duration of ICU stay, duration of antibiotic use, post-operative hospital stay duration, total healthcare expenses | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 15 | Wang et al. [37] | 2015 | 102 | 102 | 148/56 | ≥ 18 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Electroacupuncture pretreatment, once, 30 min | Sham electroacupuncture | Neiguan (PC6); Ximen (PC4) | cTnI (24 h), MI4a incidence (24 h), LVEDD (0, 3, and 6 m), EDV, SV, LVEF, MACE rate (24 m), hs-CRP (24 h), TNF-α (24 h), IL-6 (24 h), IL-10 (24 h), HMGB1 (24 h), PET/CT imaging myocardial metabolic activity | 24 months | Shaanxi, China |

| 16 | Ni et al. [21] | 2012 | 34 | 36 | 34/36 | 2–12 | Pediatric congenital heart disease | Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of acupuncture points, 30 min preoperatively | Sham transcutaneous electrical stimulation at acupuncture points | Neiguan (PC6) | cTnI (0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h), hs-CRP (0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h), IL-6 (0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h), IL-10 (0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h), TNF-a (0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h), mechanical ventilation time, urinary output, rate of in-hospital reoperation, postoperative complications, length of stay in the ICU, duration of hospital stay, in-hospital mortality rate, muscle strength score | Not mentioned | Shaanxi, China |

| 17 | Pei et al. [38] | 2024 | 70 | 70 | 93/47 | 53–80 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Electroacupuncture was carried out for 30 min each time, once a day, for a total of 3 days | Sham electroacupuncture | Neiguan (PC6); Daling (PC7); Xiajuxu point (ST39) | Fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, IL-6, Hs-CRP, AoPPs, OX-LDL, Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), heart rate variability | 3 days | Beijing, China |

| 18 | Mu et al. [39] | 2024 | 47 | 47 | 56/38 | 42–53 | Heart bypass surgery | Electroacupuncture pretreatment was conducted for 30 min each day and continued for 5 consecutive days | None | Neiguan (PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | cTnI (12 and 24 h), hs-CRP (12 and 24 h), LVEF (5 days), E/A (5 days), the incidence of postoperative adverse cardiac events | Not mentioned | Hebei, China |

| 19 | Wang [40] | 2016 | 38 | 38 | 47/29 | 45–77 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture was performed five times a week, with each session lasting 25 min | None | Neiguan (PC6); Shenmen (HT6); Xinshu (BL15); Daling (PC7); Sanyinjiao (SP6) | TG (6 weeks), TC (6 weeks), LDH (6 weeks), 6 min walk test (6MWT) (6 weeks), LEDV (6 weeks), Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) scale (6 weeks) | Not mentioned | Hubei, China |

| 20 | Zhang [41] | 2022 | 42 | 45 | 53/34 | 47–76 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture and moxibustion were carried out once a week for 30 min each time, starting before reperfusion treatment and continuing until the seventh day after the operation | None | Neiguan (PC6) | CK-MB (6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h and 7 days), MYO (6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h and 7 days), cardiac arrhythmia (total premature ventricular contractions, single premature ventricular contractions, runs of premature ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia), NT-proBNP level (24 and 72 h and 7 days), EDV (7 days), ESV (7 days), IVS (7 days), IVPW (7 days), LVE (7 days) | Not mentioned | Hubei, China |

| 21 | Ping et al. [42] | 2003 | 24 | 24 | None | Not mentioned | Coronary artery bypass grafting | Electroacupuncture pretreatment was carried out once, lasting for 20–30 min | None | Neiguan(PC6); Lieque (LU7); Yunmen (LU2) | IL-8, SOD, MDA, ultrastructural changes of cardiomyocytes | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

| 22 | Si [43] | 2020 | 19 | 18 | 25/12 | 35–85 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation was given for 30 min each time, once a day, for a total of 3 days of treatment | None | Neiguan (PC6); Daling (PC7); Jueyinshu (BL14); Xinshu (BL15) | TCM clinical symptom score (24 h), overall efficacy evaluation, self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) score (24 h), self-rating depression scale (SDS) score (24 h), CK, CK-MB, LDH, MYO | Not mentioned | Hunan, China |

| 23 | He et al. [44] | 2024 | 38 | 38 | 35/41 | 40–68 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Auricular point pressing with beans was performed twice a day for 4 weeks | None | Shenmen (TF4), sympathetic (AH6a), subcortex, heart (CO15), spleen (CO13), stomach (CO13) | Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), PSQI, 6 min walk test (6MWT), LVEDD, LVESD, LVEF, CI, SAQ, World Health Organization quality of life–brief (WHOQOL–BREF), coincidence of adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cardiac arrhythmia) | 6 months | Jiangxi, China |

| 24 | Jia et al. [45] | 2022 | 15 | 15 | 17/13 | 45–71 | Heart valve replacement surgery | Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation, starting 30 min before the operation and lasting until the operation is completed | Sham transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation | Shenting (DU24), Dazhui (DU14) | The incidence of POD (1, 2, and 3 days), cardiopulmonary bypass time, duration of aortic block, operation time, total fluid output, total fluid intake, sufentanil dosage, propofol dosage, sevoflurane dosage, duration of tube-indwelling, duration of ICU stay, duration of hospital stay, fentanyl dosage, midazolam dosage, IL-6 (1 and 3 days) | Not mentioned | Guangdong, China |

| 25 | Wang et al. [46] | 2012 | 20 | 20 | 21/19 | 30–60 | Mitral valve replacement | Electroacupuncture induction was carried out from 1 h before the operation until the operation was completed | None | Neiguan (PC6); Yunmen (LU2); Lieque (LU7) | RBC-C3b RR (0.5 and 24 h), RBC-ICR(0.5 and 24 h), MDA(0.5 and 24 h), SOD(0.5 and 24 h) | Not mentioned | Guizhou, China |

| 26 | Shao et al. [47] | 2024 | 21 | 21 | 30/12 | 44–68 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) | Acupuncture was administered three times a week, with each session lasting 30 min and a treatment course of 8 weeks | None | Jiaji (EX-B2) | 6-min walk test (6MWT) (8w), LVEF (8 weeks), grip strength of a single hand (8 weeks), the number of times of voluntarily lifting a unilateral lower limb within 10 s (8 weeks), cardiac arrhythmia status (8 weeks), International Classification of Functioning (ICF) Score (8 weeks) | Not mentioned | Shanghai, China |

3.3. Method Quality Assessment of Included Studies

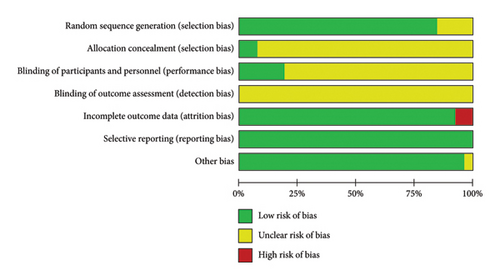

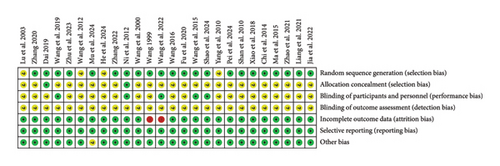

The risk assessment tool from the Cochrane Handbook was used to evaluate the included studies, indicating a generally moderate risk across most literature studies. All 26 studies were RCTs, with 18 [25–36, 39–41, 43, 45, 47] employing the random number table method, two [24, 37] utilizing computer-generated randomization, two [21, 38] implementing envelope randomization, and four [20, 42, 44, 46] mentioning randomization without specifying the method. Regarding allocation concealment, only two studies [21, 24] explicitly described their concealment strategy. In terms of blinding, five studies [21, 29, 30, 37, 47] reported blinding both researchers and participants, while none of the 16 studies mentioned blinding of outcome assessors. Data completeness issues were noted in two studies [31, 32]. For reporting bias, all 26 studies adhered to their prespecified outcome reporting. No additional biases were detected, as baseline characteristics were comparable across all studies. A detailed risk of bias assessment is presented in Figures 2 and 3.

3.4. Meta-Analysis Results of Acupuncture Treatment of Myocardial I/R Injury

3.4.1. Myocardial Enzyme Level

3.4.1.1. cTnI

Eight studies [20, 21, 24, 26, 28, 30, 37, 39] reported cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels. One study [37] converted measurement data into categorical variables, precluding statistical extraction. Substantial heterogeneity arose due to variations in study design and detection timing, necessitating combined and subgroup analyses. Meta-analysis revealed significant differences in cTnI levels at 0.5, 2, 3, 6, 8, and 24 h between the acupuncture and control groups, with acupuncture significantly reducing cTnI levels. However, no significant differences were observed at 0.25, 1, 12, 48, or 72 h. The overall combined effect size for cTnI was (SMD = −1.22, 95% CI [−1.57, −0.87]), Z = 6.77, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in myocardial enzyme levels with acupuncture. Notably, acupuncture exhibited a “parabolic” trend, predominantly mitigating peak cTnI elevation postmyocardial injury, as detailed in Table 3 and Supporting Figure 1.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cTnI (0.25 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 0.27 ± 0.08, 25 | 0.26 ± 0.47, 25 | 0.03 [−0.53, 0.58] | 0.10 | 0.92 | ||

| cTnI (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 3.07 ± 0.63, 25 | 4.67 ± 0.51, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 0.226 ± 0.021, 20 | 0.275 ± 0.019, 20 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 6.96 ± 2.13, 34 | 9.47 ± 1.93, 36 | |||||

| n = 79 | n = 81 | −2.08 [−3.09, −1.07] | 84 | 0.002 | 4.04 | < 0.0001 | |

| cTnI (1 h) | |||||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 0.224 ± 0.025, 20 | 0.256 ± 0.024, 20 | |||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 0.14 ± 0.39, 30 | 0.15 ± 0.37, 30 | |||||

| n = 50 | n = 50 | −0.63 [−1.86, 0.60] | 88 | 0.004 | 1.01 | 0.31 | |

| cTnI (2 h) | |||||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 0.212 ± 0.022, 20 | 0.259 ± 0.021, 20 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 11.21 ± 2.03, 34 | 14.69 ± 1.93, 36 | |||||

| n = 54 | n = 56 | −1.87 [−2.33, −1.42] | 0 | 0.41 | 8.07 | < 0.00001 | |

| cTnI (3 h) | |||||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 3.44 ± 3.68, 30 | 5.51 ± 3.67, 30 | −0.56 [−1.07, −0.04] | 2.11 | 0.03 | ||

| cTnI (6 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 4.08 ± 0.94, 25 | 5.62 ± 1.09, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 0.197 ± 0.21, 20 | 0.246 ± 0.025, 20 | |||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 5.74 ± 3.62, 30 | 7.89 ± 4.04, 30 | |||||

| n = 75 | n = 75 | −0.78 [−1.44, −0.11] | 74 | 0.02 | 2.30 | 0.02 | |

| cTnI (8 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 9.18 ± 1.74, 34 | 13.24 ± 1.93, 36 | −2.18 [−2.78, −1.58] | 7.15 | < 0.00001 | ||

| cTnI (12 h) | |||||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 6.22 ± 3.53, 30 | 8.34 ± 5.93, 30 | |||||

| Mu et al. 2024 | 0.65 ± 0.1, 47 | 0.91 ± 0.13, 47 | |||||

| n = 77 | n = 77 | −1.33 [−3.08, 0.43] | 96 | < 0.00001 | 1.48 | 0.14 | |

| cTnI (24 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 2.48 ± 0.75, 25 | 3.69 ± 0.89, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 0.171 ± 0.016, 20 | 0.221 ± 0.018, 20 | |||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 6.22 ± 3.53, 30 | 8.34 ± 5.93, 30 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 6.14 ± 1.01, 34 | 8.5 ± 1.11, 36 | |||||

| Mu et al. 2024 | 0.41 ± 0.08, 47 | 0.67 ± 0.11, 47 | |||||

| Zhu et al. 2023 | 0.008 ± 0.1393, 28 | 0.04 ± 0.1209, 29 | |||||

| Dai 2019 | 0.0727 ± 0.03118, 30 | 0.0957 ± 0.04042, 30 | |||||

| n = 214 | n = 217 | −1.47 [−2.27,−0.68] | 92 | < 0.00001 | 3.65 | 0.0003 | |

| cTnI (48 h) | |||||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 3.97 ± 3.83, 30 | 5.43 ± 7.6, 30 | |||||

| Dai 2019 | 0.0923 ± 0.03081, 30 | 0.126 ± 0.04031, 30 | |||||

| n = 60 | n = 60 | −0.58 [−1.25, 0.10] | 70 | 0.07 | 1.68 | 0.09 | |

| cTnI (72 h) | |||||||

| Yang et al. 2010 | 1.97 ± 2.07, 30 | 2.65 ± 2.45, 30 | −0.30 [−0.80, 0.21] | 1.14 | 0.25 | ||

| Total | n = 728 | n = 737 | −1.22 [−1.57,−0.87] | 89 | < 0.00001 | 6.77 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.1.2. CK-MB

Five studies [24, 26, 27, 41, 43] reported CK-MB levels. Given variations in study design and detection timing, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were performed. Heterogeneity among the studies was minimal. The meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in CK-MB levels at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h and 14 days in the acupuncture group compared to controls. However, no significant differences were observed at 72 h or 7 days. The overall combined effect size for CK-MB was (SMD = −0.71, 95% CI [−0.87, −0.55]), Z = 8.63, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in CK-MB levels with acupuncture. These findings indicate that acupuncture effectively lowers myocardial CK-MB levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 4 and Supporting Figure 2.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD fixed (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK-MB (6 h) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 389.35 ± 12.7, 42 | 453.96 ± 19.54, 45 | −3.86 [−4.58,−3.14] | 10.48 | < 0.00001 | ||

| CK-MB (12 h) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 204.49 ± 16.66, 42 | 376.21 ± 39.06, 45 | −5.60 [−6.55,−4.65] | 11.56 | < 0.00001 | ||

| CK-MB (24 h) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 126.57 ± 2.67, 42 | 228.53 ± 7.66, 45 | |||||

| Zhu et al. 2023 | 1.2 ± 1.19, 30 | 1.5 ± 2.56, 30 | |||||

| Dai 2019 | 46.43 ± 8.02, 28 | 53.03 ± 7.81, 29 | |||||

| n = 100 | n = 104 | −0.78 [−1.15,−0.41] | 99 | < 0.00001 | 4.17 | < 0.0001 | |

| CK-MB (48 h) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 51.1 ± 8.13, 43 | 50.89 ± 5.57, 45 | |||||

| Dai 2019 | 47.63 ± 8.02, 30 | 54.93 ± 7.53, 30 | |||||

| n = 73 | n = 75 | −0.33 [−0.66,−0.00] | 87 | 0.006 | 1.98 | 0.05 | |

| CK-MB (72 h) | |||||||

| Fu et al. 2020 | 12.08 ± 3.81, 19 | 11.09 ± 5.03, 18 | |||||

| Zhang 2022 | 20.99 ± 4.83, 42 | 21.31 ± 3.47, 45 | |||||

| n = 61 | n = 63 | 0.01 [−0.34, 0.36] | 0 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.95 | |

| CK-MB (7 days) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 6.1 ± 0.96, 42 | 6.34 ± 1.69, 45 | −0.17 [−0.59, 0.25] | 0.80 | 0.42 | ||

| CK-MB (14 days) | |||||||

| Liang et al. 2021 | 25.16 ± 8.14, 43 | 31.54 ± 8.35, 43 | −0.77 [−1.21,−0.33] | 3.43 | 0.0006 | ||

| Total | n = 403 | n = 420 | −0.71 [−0.87,−0.55] | 97 | < 0.00001 | 8.63 | < 0.00001 |

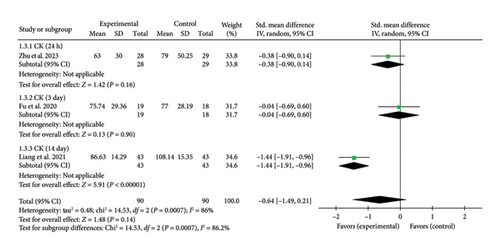

3.4.1.3. CK

Three studies [26, 27, 43] reported myocardial enzyme CK levels. The overall combined effect size was (SMD = −0.64, 95% CI [−1.49, 0.21]), Z = 1.48, and p = 0.14, indicating no statistically significant effect of acupuncture on CK levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot illustrating CK levels is presented in Figure 4.

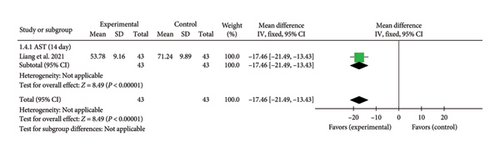

3.4.1.4. AST

A single study [27] reported AST levels on Day 14. The aggregated effect size was (MD = −17.46, 95% CI [−21.49, −13.43]), Z = 8.49, and p < 0.00001, demonstrating a significant reduction in AST levels with acupuncture in patients with myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot for AST levels is shown in Figure 5.

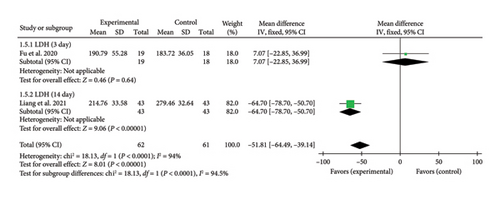

3.4.1.5. LDH

Two studies [27, 43] reported LDH levels on Days 3 and 14. One study [27] found a significant reduction in LDH levels at Day 14 (MD = −64.70, 95% CI [−78.70, −50.70]), Z = 9.06, and p < 0.00001, indicating a significant difference between the acupuncture and control groups. In contrast, another study [43] reported no significant difference in LDH levels at Day 3 (MD = 7.07, 95% CI [−22.85, 36.99]), Z = 0.46, and p = 0.64. The forest plot for LDH levels is presented in Figure 6.

3.4.1.6. BNP

Two studies [31, 41] reported BNP levels. Due to variations in study design and detection timing, substantial heterogeneity was observed, necessitating combined and subgroup analyses. The meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in BNP levels at Days 1, 3, 7, and 14 in the acupuncture group compared to controls. The overall combined effect size for BNP was (SMD = −2.89, 95% CI [−4.95, −0.83]), Z = 2.75, and p = 0.006, confirming a statistically significant reduction in BNP levels with acupuncture. These findings indicate that acupuncture effectively lowers BNP levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 5 and Supporting Figure 3.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP(1d) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 972.21 ± 120.24, 42 | 1746.51 ± 230.64, 45 | −4.13 [−4.89,−3.38] | 10.71 | < 0.00001 | ||

| BNP(3d) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 529.24 ± 84.18, 42 | 1034.27 ± 170.04, 45 | −3.69 [−4.39,−2.99] | 10.32 | < 0.00001 | ||

| BNP(7d) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 227.05 ± 48.28, 42 | 596.11 ± 147.3, 45 | −3.29 [−3.94,−2.64] | 9.87 | < 0.00001 | ||

| BNP(14d) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2022 | 3.35 ± 1.01, 100 | 3.87 ± 1.08, 100 | −0.50 [−0.78,−0.21] | 3.45 | 0.0006 | ||

| Total | n = 226 | n = 235 | −2.89 [−4.95,−0.83] | 98 | < 0.00001 | 2.75 | 0.006 |

3.4.2. Inflammatory Factor Level

3.4.2.1. hs-CRP

Seven studies [21, 24, 34, 35, 37–39] reported hs-CRP levels. Due to variations in study design and detection timing, substantial heterogeneity was observed, necessitating a meta-analysis and subgroup analysis. The meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in hs-CRP levels at 0.5, 2, 8, 12, and 24 h and 30 days in the acupuncture group compared to controls. However, no significant differences were observed at 6, 48, and 72 h. The overall combined effect size for hs-CRP was (SMD = −1.34, 95% CI [−1.87, −0.80]), Z = 4.92, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in hs-CRP levels with acupuncture. These findings indicate that acupuncture effectively reduces hs-CRP levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 6 and Supporting Figure 4.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hs-CRP(0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 608 ± 74.67, 34 | 736 ± 149.33, 36 | −1.06 [−1.57,−0.56] | 4.15 | < 0.0001 | ||

| hs-CRP(2 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 736 ± 117.33, 34 | 992 ± 160, 36 | −1.80 [−2.36,−1.24] | 6.29 | < 0.00001 | ||

| hs-CRP(6 h) | |||||||

| Zhang 2020 | 12.8 ± 2.98, 30 | 12.23 ± 2.43, 30 | 0.21 [−0.30, 0.71] | 0.80 | 0.42 | ||

| hs-CRP(8 h) | |||||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 12.51 ± 1.5, 47 | 16.81 ± 1.64, 47 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 1525.33 ± 181.33, 34 | 2133.33 ± 170.67, 36 | |||||

| n = 81 | n = 83 | −3.02 [−3.71,−2.34] | 54 | 0.14 | 8.65 | < 0.00001 | |

| hs-CRP(12 h) | |||||||

| Mu et al. 2024 | 60.22 ± 5.03, 47 | 68.74 ± 5.37, 47 | −1.62 [−2.09,−1.16] | 6.79 | < 0.00001 | ||

| hs-CRP(24 h) | |||||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 8.43 ± 1.45, 47 | 13.63 ± 1.64, 47 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 1807.14 ± 178.57, 102 | 1914.29 ± 200, 102 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 2976 ± 149.33, 34 | 3242.67 ± 138.67, 36 | |||||

| Mu et al. 2024 | 43.26 ± 4.97, 47 | 50.14 ± 5.63, 47 | |||||

| Dai 2019 | 8.13 ± 0.724, 30 | 8.53 ± 0.867, 30 | |||||

| n = 260 | n = 262 | −1.48 [−2.36,−0.59] | 95 | < 0.00001 | 3.27 | 0.001 | |

| hs-CRP(48 h) | |||||||

| Dai 2019 | 4.17 ± 0.685, 30 | 4.57 ± 0.908, 30 | −0.49 [−1.01, 0.02] | 1.87 | 0.06 | ||

| hs-CRP(72 h) | |||||||

| Pei 2024 | −0.01 ± 0.01, 70 | −0.01 ± 0.03, 70 | 0.00 [−0.33, 0.33] | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| hs-CRP(30d) | |||||||

| Zhang 2020 | 7.19 ± 1.52, 30 | 8.13 ± 1.33, 30 | −0.65 [−1.17,−0.13] | 2.45 | 0.01 | ||

| Total | n = 616 | n = 624 | −1.34 [−1.87,−0.80] | 94 | < 0.00001 | 4.92 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.2.2. TNF-α

Four studies [21, 25, 29, 37] reported TNF-α levels, exhibiting substantial heterogeneity due to variations in study design and detection timing. To address this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in TNF-α levels at 0, 0.5, 6, 24, and 72 h and 14 days in the acupuncture group compared to controls. However, no significant difference was observed at 2 h. The overall combined effect size for TNF-α was (SMD = −1.13, 95% CI [−1.41, −0.85]), Z = 7.84, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in TNF-α levels with acupuncture. These findings suggest that acupuncture effectively lowers TNF-α levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as presented in Table 7 and Supporting Figure 5.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 16.3 ± 2.6, 30 | 21.2 ± 3.7, 30 | −1.51 [−2.09,−0.93] | 5.13 | < 0.00001 | ||

| TNF-α (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 63.13 ± 6.57, 34 | 79.29 ± 10.61, 36 | −1.80 [−2.36,−1.24] | 6.30 | < 0.00001 | ||

| TNF-α (2 h) | |||||||

| Shan et al. 2010 | 98.67 ± 35.12, 15 | 123.1 ± 47.21, 15 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 97.98 ± 14.14, 34 | 104.04 ± 21.72, 36 | |||||

| n = 49 | n = 51 | −0.40 [−0.79,−0.00] | 0 | 0.58 | 1.96 | 0.05 | |

| TNF-α (6 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 32.1 ± 5.1, 30 | 38.7 ± 5.6, 30 | −1.22 [−1.77,−0.66] | 4.30 | < 0.0001 | ||

| TNF-α (8 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 102.02 ± 16.16, 34 | 109.09 ± 18.69, 36 | −0.40 [−0.87, 0.07] | 1.65 | 0.10 | ||

| TNF-α (24 h) | |||||||

| Shan et al. 2010 | 35.17 ± 10.56, 15 | 49.01 ± 13.75, 15 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 111.9 ± 13.1, 102 | 136.9 ± 20.24, 102 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 138.38 ± 23.74, 34 | 156.57 ± 25.25, 36 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 41.5 ± 6.9, 30 | 52.6 ± 8.7, 30 | |||||

| n = 181 | n = 183 | −1.20 [−1.57,−0.83] | 54 | 0.09 | 6.34 | < 0.00001 | |

| TNF-α (72 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 38.2 ± 6.4, 30 | 49.7 ± 8.3, 30 | −1.53 [−2.11,−0.95] | 5.18 | < 0.00001 | ||

| TNF-α (14 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2022 | 30.66 ± 4.04, 100 | 36.59 ± 4.21, 100 | −1.43 [−1.74,−1.12] | 9.01 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 488 | n = 496 | −1.13 [−1.41,−0.85] | 74 | < 0.0001 | 7.84 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.2.3. IL-10

Five studies [21, 25, 29, 35, 37] reported IL-10 levels, exhibiting substantial heterogeneity due to variations in study design and detection timepoints. To account for this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The analysis revealed a significant increase in IL-10 levels at 0, 0.5, 6, 8, 24, and 72 h in the acupuncture group compared to controls. However, no significant difference was observed at 2 h. The overall combined effect size for IL-10 was (SMD = 1.31, 95% CI [0.74, 1.87]), Z = 4.55, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant elevation in IL-10 levels with acupuncture. These findings suggest that acupuncture effectively enhances IL-10 levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 8 and Supporting Figure 6.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-10 (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 76 ± 7, 30 | 68 ± 7, 30 | 1.13 [0.58, 1.68] | 4.044 | < 0.0001 | ||

| IL-10 (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 87.5 ± 8.75, 34 | 98.27 ± 8.75, 36 | −1.22 [−1.73,−0.70] | 4.65 | < 0.00001 | ||

| IL-10 (2 h) | |||||||

| Shan et al. 2010 | 595.8 ± 46.7, 15 | 381.6 ± 23.5, 15 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 107.36 ± 5.72, 34 | 103.65 ± 12.79, 36 | |||||

| n = 49 | n = 51 | 2.94 [−2.23, 8.10] | 97 | < 0.00001 | 1.11 | 0.26 | |

| IL-10 (6 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 92 ± 11, 30 | 77 ± 8, 30 | 1.54 [0.96, 2.12] | 5.20 | < 0.00001 | ||

| IL-10 (8 h) | |||||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 337.1 ± 53.17, 47 | 260.18 ± 42.99, 47 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 98.27 ± 10.1, 34 | 91.2 ± 9.76, 36 | |||||

| n = 81 | n = 83 | 1.14 [0.29, 2.00] | 85 | 0.01 | 2.62 | 0.009 | |

| IL-10 (24 h) | |||||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 226.24 ± 40.72, 47 | 154.98 ± 35.07, 47 | |||||

| Shan et al. 2010 | 182.9 ± 25.2, 15 | 141.5 ± 21.8, 15 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 222.69 ± 36.13, 102 | 148.74 ± 30.25, 102 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 92.88 ± 7.4, 34 | 84.81 ± 7.4, 36 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 107 ± 13, 30 | 96 ± 12, 30 | |||||

| n = 228 | n = 230 | 1.55 [1.00, 2.11] | 83 | < 0.0001 | 5.47 | < 0.00001 | |

| IL-10 (72 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 94 ± 10, 30 | 82 ± 9, 30 | 1.25 [0.69, 1.80] | 4.39 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 482 | n = 490 | 1.31 [0.74, 1.87] | 93 | < 0.00001 | 4.55 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.2.4. IL-6

Seven studies [21, 29, 34, 35, 37, 38, 45] reported IL-6 levels, with substantial heterogeneity due to variations in study design and detection timepoints. To address this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in IL-6 levels at 0, 0.5, 2, 8, and 24 h and 30 days in the acupuncture group compared to controls. Acupuncture did not demonstrate a significant reduction in IL-6 levels at the 6 and 72-h time points, as no statistically significant differences were observed between the acupuncture and control groups. The overall combined effect size for IL-6 was (SMD = −1.53, 95% CI [−2.01, −1.06]), Z = 6.33, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in IL-6 levels with acupuncture. These findings highlight the efficacy of acupuncture in lowering IL-6 levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 9 and Supporting Figure 7.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 27.6 ± 4.6, 30 | 35.4 ± 5.3, 30 | −1.55 [−2.13, −0.97] | 5.23 | < 0.00001 | ||

| IL-6 (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 208.69 ± 23.4, 34 | 247.06 ± 29.95, 36 | −1.41 [−1.93, −0.88] | 5.24 | < 0.00001 | ||

| IL-6 (2 h) | |||||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 239.57 ± 24.33, 34 | 267.65 ± 29.95, 36 | −1.01 [−1.51, −0.52] | 3.98 | < 0.0001 | ||

| IL-6 (6 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 41.2 ± 5.4, 30 | 49.4 ± 6.1, 30 | |||||

| Zhang 2020 | 65.47 ± 9.57, 30 | 65.43 ± 10.3, 30 | |||||

| n = 60 | n = 60 | −0.69 [−2.07, 0.69] | 92 | 0.0003 | 0.99 | 0.32 | |

| IL-6 (8 h) | |||||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 187.74 ± 32.26, 47 | 230.32 ± 40.65, 47 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 196.52 ± 23.4, 34 | 235.83 ± 28.07, 36 | |||||

| n = 81 | n = 83 | −1.29 [−1.63, −0.95] | 0 | 0.32 | 7.48 | < 0.00001 | |

| IL-6 (24 h) | |||||||

| Jia et al. 2022 | 12.72 ± 3.51, 15 | 18.95 ± 1.89, 15 | |||||

| Zhao et al. 2021 | 116.13 ± 38.06, 47 | 208.39 ± 42.58, 47 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 125.7 ± 21.79, 102 | 211.17 ± 41. 06, 102 | |||||

| Ni et al. 2012 | 186.23 ± 27.14, 34 | 217.11 ± 37.43, 36 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 39.2 ± 5.5, 30 | 46.1 ± 5.7, 30 | |||||

| n = 228 | n = 230 | −1.83 [−2.54, −1.11] | 89 | < 0.00001 | 5.02 | < 0.00001 | |

| IL-6 (72 h) | |||||||

| Jia et al. 2022 | 5.7 ± 1.04, 15 | 7.88 ± 2.49, 15 | |||||

| Pei et al. 2024 | −0.008 ± 0.009, 70 | −0.006 ± 0.007, 70 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2019 | 15.7 ± 3.1, 30 | 46.1 ± 5.7, 30 | −6.54 [−7.85, −5.23] | 9.77 | < 0.00001 | ||

| n = 115 | n = 115 | −2.55 [−5.30, 0.20] | 98 | < 0.00001 | 1.82 | 0.07 | |

| IL-6 (30 days) | |||||||

| Zhang 2020 | 16.41 ± 5.95, 30 | 21.3 ± 3.4, 30 | −1.00 [−1.53, −0.46] | 3.62 | 0.0003 | ||

| Total | n = 612 | n = 620 | −1.53 [−2.01, −1.06] | 92 | < 0.00001 | 6.33 | < 0.00001 |

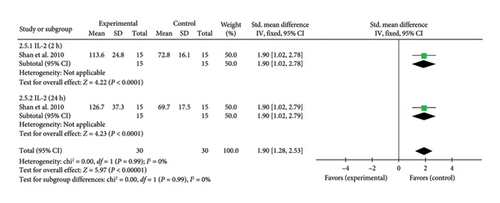

3.4.2.5. IL-2

A single study [25] reported IL-2 levels, exhibiting significant heterogeneity due to differences in study design and detection timepoints. To account for this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The combined effect size for IL-2 levels at 2 h was (SMD = 1.90, 95% CI [1.02, 2.78]), Z = 4.22, and p < 0.0001, indicating a significant increase in IL-2 levels with acupuncture. Similarly, at 24 h, the combined effect size was (SMD = 1.90, 95% CI [1.02, 2.79]), Z = 4.23, and p < 0.0001, confirming a statistically significant elevation in IL-2 levels in patients with myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot for IL-2 levels is presented in Figure 7.

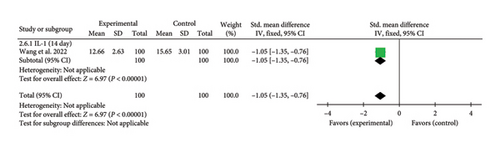

3.4.2.6. IL-1

A single study [31] reported IL-1 levels on Day 14. The combined effect size was (SMD = −1.05, 95% CI [−1.35, −0.76]), Z = 6.97, and p < 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant reduction in IL-1 levels with acupuncture in patients with myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot for IL-1 levels is presented in Figure 8.

3.4.2.7. IL-8

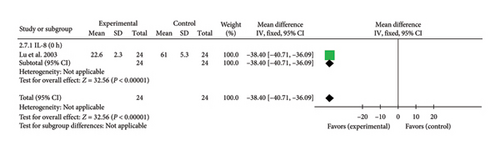

A single study [42] reported IL-8 levels at 0 h. The effect size was (MD = −38.40, 95% CI [−40.71, −36.09]), Z = 32.56, and p < 0.00001, indicating a statistically significant reduction in IL-8 levels with acupuncture in patients with myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot for IL-8 levels is presented in Figure 9

3.4.3. Oxidative Stress Factor Levels

3.4.3.1. MDA

Five studies [28, 30, 33, 42, 46] reported MDA levels, exhibiting considerable heterogeneity due to variations in study design and detection timepoints. To address this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The meta-analysis revealed significant reductions in MDA levels at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 24 h in the acupuncture group compared to controls, while no significant difference was observed at 0.25 h. The overall combined effect size for MDA was (SMD = −1.78, 95% CI [−2.36, −1.20]), Z = 6.00, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant reduction in MDA levels with acupuncture. These findings highlight the efficacy of acupuncture in mitigating oxidative stress in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 10 and Supporting Figure 8.

| Index | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2000 | 4.51 ± 1.58, 10 | 4.81 ± 0.99, 9 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2012 | 8.3 ± 1, 20 | 10.9 ± 1.4, 20 | |||||

| Lu et al. 2003 | 4.9 ± 0.4, 24 | 5.6 ± 0.2, 24 | |||||

| n = 54 | n = 53 | −1.52 [−2.70,−0.34] | 85 | 0.002 | 2.53 | 0.01 | |

| MDA (0.25 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 4.57 ± 1.87, 25 | 4.41 ± 2.01, 25 | 0.08 [−0.47, 0.64] | 0.29 | 0.77 | ||

| MDA (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 8.47 ± 2.64, 25 | 11.84 ± 3.02, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 5.8 ± 2.1, 20 | 8.6 ± 2.8, 20 | |||||

| n = 45 | n = 45 | −1.14 [−1.59, −0.69] | 0 | 0.90 | 4.99 | < 0.00001 | |

| MDA (1 h) | |||||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 5.6 ± 0.5, 20 | 8.2 ± 0.6, 20 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2000 | 4.67 ± 2.38, 10 | 7.99 ± 1.71, 9 | |||||

| n = 30 | n = 29 | −3.05 [−6.08, −0.01] | 93 | 0.0002 | 1.97 | 0.05 | |

| MDA (2 h) | |||||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 6 ± 0.4, 20 | 7.3 ± 0.5, 20 | −2.81 [−3.71, −1.92] | 6.14 | < 0.00001 | ||

| MDA (6 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 11.02 ± 2.65, 25 | 15.11 ± 2.83, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 5.7 ± 0.4, 20 | 6.9 ± 0.4, 20 | |||||

| n = 45 | n = 45 | −2.16 [−3.61, −0.72] | 85 | 0.010 | 2.95 | 0.003 | |

| MDA (24 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 8.37 ± 1.98, 25 | 12.41 ± 2.31, 25 | |||||

| Xiao et al. 2018 | 4.6 ± 0.3, 20 | 5.2 ± 0.3, 20 | |||||

| n = 45 | n = 45 | −1.90 [−2.40, −1.39] | 0 | 0.83 | 7.36 | < 0.00001 | |

| Total | n = 264 | n = 262 | −1.78 [−2.36, −1.20] | 87 | < 0.00001 | 6.00 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.3.2. SOD

Four studies [30, 33, 42, 46] reported SOD levels, exhibiting substantial heterogeneity due to differences in study design and detection timepoints. To address this, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The meta-analysis revealed significant differences in SOD levels at 0, 0.5, 1, 6, and 24 h, with acupuncture significantly increasing SOD levels compared to the control group. However, no significant difference was observed at 0.25 h. The overall combined effect size for SOD was (SMD = 0.98, 95% CI [0.55, 1.41]), Z = 4.50, and p < 0.00001, confirming a statistically significant enhancement of SOD levels with acupuncture. These findings suggest that acupuncture effectively promotes antioxidant activity in patients with myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 11 and Supporting Figure 9.

| Index | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOD (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2000 | 89.9 ± 14.74, 10 | 69.14 ± 9.49, 9 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2012 | 80 ± 11, 20 | 71 ± 12, 20 | |||||

| Lu et al. 2023 | 19.2 ± 2.8, 24 | 16.6 ± 5, 24 | |||||

| n = 54 | n = 53 | 0.84 [0.39, 1.28] | 17 | 0.30 | 3.67 | 0.0002 | |

| SOD (0.25 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 30.2 ± 4.37, 25 | 31.18 ± 5.43, 25 | −0.20 [−0.75, 0.36] | 0.69 | 0.49 | ||

| SOD (0.5 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 24.8 ± 5.14, 25 | 17.03 ± 5.06, 25 | 1.50 [0.87, 2.13] | 4.64 | < 0.00001 | ||

| SOD (1 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2000 | 102.09 ± 16.59, 10 | 68 ± 24.77, 9 | 1.56 [0.50, 2.62] | 2.89 | 0.004 | ||

| SOD (6 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 21.5 ± 3.67, 25 | 16.1 ± 3.25, 25 | 1.53 [0.90, 2.17] | 4.72 | < 0.00001 | ||

| SOD (24 h) | |||||||

| Ma et al. 2015 | 24.57 ± 5.04, 25 | 18.42 ± 4.35, 25 | 4.11 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Wang et al. 2012 | 85 ± 12, 20 | 77 ± 13, 20 | |||||

| n = 45 | n = 45 | 0.96 [0.32, 1.61] | 53 | 0.14 | 2.92 | 0.004 | |

| Total | n = 184 | n = 182 | 0.98 [0.55, 1.41] | 72 | 0.0004 | 4.50 | < 0.00001 |

3.4.4. Echocardiogram Indexes

3.4.4.1. LVEF

Eight studies [27, 31, 37, 39–41, 44, 47] reported echocardiographic LVEF. Given the heterogeneity arising from variations in study design and assessment time points, both meta-analysis and subgroup analysis were conducted. The meta-analysis and effect size evaluation revealed a significant difference in echocardiographic LVEF between the acupuncture and control groups at Days 0, 7, 14, 28, 42, 56, 90, and 180. Acupuncture was associated with a significant improvement in LVEF compared to the control group at these time points, except at Day 5, where no statistically significant difference was observed. The overall pooled effect size for echocardiographic LVEF was SMD = 1.32 (95% CI [0.54, 2.09]), Z = 3.33, and p = 0.0009, indicating a significant enhancement in LVEF in patients with myocardial I/R injury in the acupuncture group, as detailed in Table 12 and Supporting Figure 10.

| Index | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (0 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 54.56 ± 0.77, 102 | 52.81 ± 0.97, 102 | 1.99 [1.65, 2.33] | 11.59 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVEF (5 days) | |||||||

| Mu et al. 2024 | 57.14 ± 3.97, 47 | 56.76 ± 3.58, 47 | 0.10 [−0.30, 0.50] | 0.48 | 0.63 | ||

| LVEF (7 days) | |||||||

| Zhang et al. 2022 | 52.6 ± 9.04, 42 | 46.96 ± 8.29, 45 | 0.65 [0.21, 1.08] | 2.93 | 0.003 | ||

| LVEF (14 days) | |||||||

| Liang et al. 2021 | 59.62 ± 5.41, 43 | 55.82 ± 5.75, 43 | |||||

| Wang et al. 2022 | 52.65 ± 8.65, 100 | 50.545 ± 8.46, 100 | |||||

| n = 143 | n = 143 | 0.43 [0.01, 0.84] | 62 | 0.10 | 2.01 | 0.04 | |

| LVEF (28 days) | |||||||

| He et al. 2024 | 48.34 ± 5.31, 38 | 40.62 ± 5.19, 38 | 1.46 [0.95, 1.96] | 5.61 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVEF (42 days) | |||||||

| Wang 2016 | 58 ± 7.1, 38 | 54 ± 6.7, 38 | 0.57 [0.11, 1.03] | 2.45 | 0.01 | ||

| LVEF (56 days) | |||||||

| Shao et al. 2024 | 57.33 ± 4.27, 21 | 54.52 ± 4.29, 21 | 0.64 [0.02, 1.27] | 2.03 | 0.04 | ||

| LVEF (90 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 55.96 ± 0.81, 102 | 52.43 ± 1.41, 102 | 3.06 [2.65, 3.46] | 14.75 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVEF (180 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 57.15 ± 0.5, 102 | 54.9 ± 0.67, 102 | 3.79 [3.33, 4.25] | 16.09 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 635 | n = 638 | 1.32 [0.54, 2.09] | 97 | < 0.00001 | 3.33 | 0.0009 |

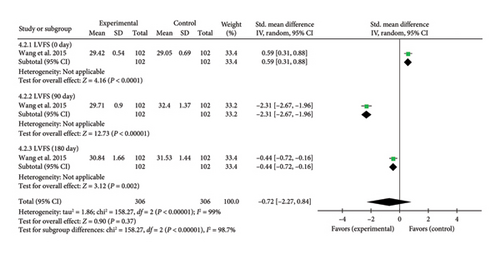

3.4.4.2. LVFS

A single study [37] reported LVFS assessed by echocardiography. Due to heterogeneity arising from variations in study design and detection timepoints, a meta-analysis and a subgroup analysis were conducted. The analysis revealed a significant increase in LVFS at Day 0 (SMD = 0.59, 95% CI [0.31, 0.88]), Z = 4.16, and p < 0.0001, indicating an initial improvement in LVFS with acupuncture in patients with myocardial I/R injury. However, at Day 90, LVFS significantly decreased in the acupuncture group compared to controls (SMD = −2.31, 95% CI [−2.67, −1.96]), Z = 12.73, and p < 0.00001. A similar trend was observed at Day 180 (SMD = −0.44, 95% CI [−0.72, −0.16]), Z = 3.12, and p = 0.002, demonstrating a sustained reduction in LVFS over time. These findings suggest a time-dependent effect of acupuncture on LVFS in myocardial I/R injury. The forest plot for LVFS is presented in Figure 10.

3.4.4.3. LVEDD

Echocardiographic LVEDD measurements were reported in three studies [27, 37, 44]. Due to variations in study design and assessment timepoints, significant heterogeneity was observed, necessitating meta-analysis and subgroup analysis. One study reported a combined effect size for LVEDD at day 0 (SMD = 0.50, 95% CI [0.22, 0.78], Z = 3.49, p = 0.0005), indicating that acupuncture significantly increased LVEDD in myocardial I/R injury. Another study reported a combined effect size at Day 14 (SMD = −0.72, 95% CI [−1.16, −0.28], Z = 3.23, and p = 0.001), suggesting that acupuncture significantly reduced LVEDD. A third study found a combined effect size at Day 28 (SMD = −1.01, 95% CI [−1.49, −0.53], Z = 4.13, and p < 0.0001), indicating that acupuncture significantly increased LVEDD conditions. Additionally, a study reported a combined effect size at Day 90 (SMD = 2.04, 95% CI [1.70, 2.37], Z = 11.76, and p < 0.00001), suggesting a significant increase in LVEDD. Finally, a study reported a combined effect size at Day 180 (SMD = −3.64, 95% CI [−4.09, −3.19], Z = 15.85, and p < 0.00001), suggesting a significant reduction in LVEDD in myocardial I/R injury, as detailed in Table 13 and Supporting Figure 11.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDD (0 h) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 49.74 ± 0.77, 102 | 49.38 ± 0.67, 102 | 0.50 [0.22, 0.78] | 3.49 | 0.0005 | ||

| LVEDD (14 days) | |||||||

| Liang et al. 2021 | 48.55 ± 2.76, 43 | 50.43 ± 2.41, 43 | −0.72 [−1.16, −0.28] | 3.23 | 0.001 | ||

| LVEDD (28 days) | |||||||

| He et al. 2024 | 56.31 ± 4.84, 38 | 61.44 ± 5.21, 38 | −1.01 [−1.49, −0.53] | 4.13 | < 0.0001 | ||

| LVEDD (90 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 50.68 ± 1.12, 102 | 48.7 ± 0.79, 102 | 2.04 [1.70, 2.37] | 11.76 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVEDD (180 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 43.56 ± 1.1, 102 | 47.28 ± 0.93, 102 | −3.64 [−4.09, −3.19] | 15.85 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 387 | n = 387 | −0.56 [−2.33, −1.21] | 99 | < 0.00001 | 0.62 | 0.53 |

3.4.4.4. LVEDV

Two studies [37, 41] assessed echocardiographic LVEDV. At Day 0, the pooled effect size (SMD = 0.85, 95% CI [0.57, 1.14], Z = 5.82, and p < 0.00001) indicated a significant increase in LVEDV following acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. However, at Day 7 (SMD = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.36, 0.48], Z = 0.29, and p = 0.77) and Day 90 (SMD = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.33, 0.22], Z = 0.38, and p = 0.71), no significant differences were observed between the acupuncture and control groups. By Day 180, the pooled effect size (SMD = −2.86, 95% CI [−3.25, −2.46], Z = 14.28, and p < 0.00001) demonstrated a significant reduction in LVEDV with acupuncture, as presented in Table 14 and Supporting Figure 12.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDV (0 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 99.51 ± 3.82, 102 | 96.48 ± 3.24, 102 | 0.85 [0.57, 1.14] | 5.82 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVEDV (7 days) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 104 ± 12.18, 42 | 103.22 ± 12.84, 45 | 0.06 [−0.36, 0.48] | 0.29 | 0.77 | ||

| LVEDV (90 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 92.64 ± 6.19, 102 | 92.96 ± 5.88, 102 | −0.55 [−0.33, 0.22] | 0.38 | 0.71 | ||

| LVEDV (180 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 83.47 ± 3.23, 102 | 96.24 ± 5.41, 102 | −2.86 [−3.25. −2.46] | 14.28 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 348 | n = 351 | −0.50 [−1.96, 0.97] | 99 | < 0.00001 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

3.4.4.5. LVESV

Two studies [37, 41] evaluated echocardiographic LVESV. At Day 0, the pooled effect size (SMD = 1.10, 95% CI [0.80, 1.39], Z = 7.30, and p < 0.00001) indicated a significant increase in LVESV following acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. However, at Day 7 (SMD = 0.31, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.73], Z = 1.43, and p = 0.15) and Day 90 (SMD = 0.22, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.50], Z = 1.57, and p = 0.12), no significant differences were observed between the acupuncture and control groups. By Day 180, the pooled effect size (SMD = 3.56, 95% CI [3.12, 4.01], Z = 15.72, and p < 0.00001) demonstrated a substantial increase in LVESV with acupuncture, as presented in Table 15 and Supporting Figure 13.

| Indicators | Acupuncture group (x ± s, n) | Control group (x ± s, n) | SMD random (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVESV (0 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 55.63 ± 1.67, 102 | 53.85 ± 1.56, 102 | 1.10 [0.80, 1.39] | 7.30 | < 0.00001 | ||

| LVESV (7 days) | |||||||

| Zhang 2022 | 31.31 ± 4.95, 42 | 29.53 ± 6.31, 45 | 0.31 [−0.11, 0.73] | 1.43 | 0.15 | ||

| LVESV (90 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 54.5 ± 3.08, 102 | 53.85 ± 2.78, 102 | 0.22 [−0.05, 0.50] | 1.57 | 0.12 | ||

| LVESV (180 days) | |||||||

| Wang et al. 2015 | 65.68 ± 2.17, 102 | 58.68 ± 1.72, 102 | 3.56 [3.12, 4.01] | 15.72 | < 0.00001 | ||

| Total | n = 348 | n = 351 | 1.29 [−0.01, 2.59] | 98 | < 0.00001 | 1.95 | 0.05 |

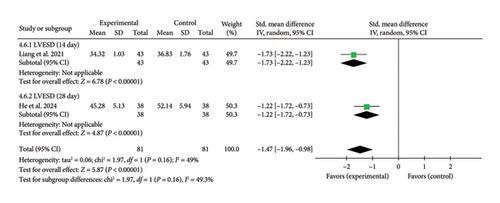

3.4.4.6. LVESD

One study [27] assessed echocardiographic LVESD. At Day 14, the pooled effect size (SMD = −1.73, 95% CI [−2.22, −1.23], Z = 6.78, and p < 0.00001) indicated a significant reduction in LVESD with acupuncture. Similarly [44], at Day 28, the pooled effect size (SMD = −1.22, 95% CI [−1.72, −0.73], Z = 4.87, and p < 0.00001) confirmed a continued decrease. These findings suggest that acupuncture effectively reduced LVESD at both time points in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for LVESD is presented in Figure 11.

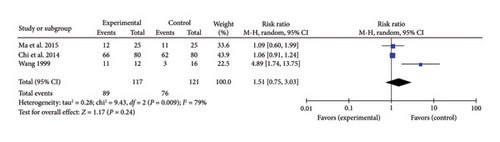

3.4.5. Heartbeat Recovery Rate

Three studies [30, 32, 36] reported a combined effect size for the heartbeat recovery rate in myocardial I/R injury cases (RR = 1.51, 95% CI [0.75, 3.03], Z = 1.17, and p = 0.24), indicating no significant improvement with acupuncture. The forest plot for heartbeat recovery rate is presented in Figure 12.

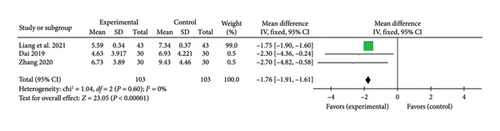

3.4.6. TCM Chest Pain Symptom Score

Three studies [24, 27, 34] reported a pooled effect size for the TCM chest pain symptom score (MD = −1.76, 95% CI [−1.91, −1.61], Z = 23.05, and p < 0.00001), indicating a significant reduction in chest pain symptoms with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for TCM chest pain symptom scores is presented in Figure 13.

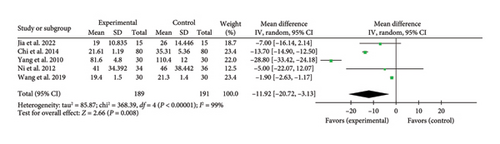

3.4.7. Duration of ICU Stay

Five studies [20, 21, 29, 36, 45] reported a pooled effect size for ICU stay duration (MD = −11.92, 95% CI [−20.72, −3.13], Z = 2.66, and p = 0.008), indicating a significant reduction with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for ICU stay duration is presented in Figure 14.

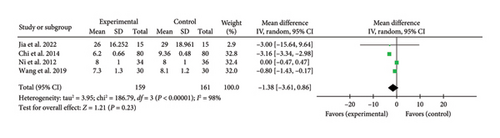

3.4.8. Duration of Hospital Stay

Four studies [21, 29, 36, 45] reported a combined effect size for hospital stay duration (MD = −1.38, 95% CI [−3.61, 0.86], Z = 1.21, and p = 0.23), indicating no significant reduction with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for hospital stay duration is presented in Figure 15.

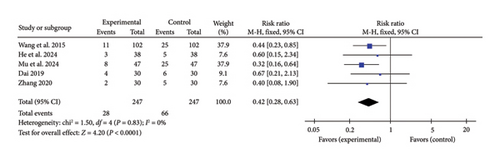

3.4.9. Incidence of MACE

Five studies [24, 34, 37, 39, 44] reported a pooled effect size for MACE incidence (RR = 0.42, 95% CI [0.28, 0.63], Z = 4.20, and p < 0.0001), demonstrating a significant reduction in MACE occurrence with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for MACE incidence is presented in Figure 16.

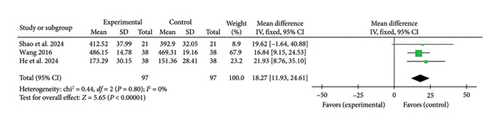

3.4.10. 6MWT

Three studies [40, 44, 47] reported a pooled effect size for the 6MWT (MD = 18.27, 95% CI [11.93, 24.61], Z = 5.65, and p < 0.00001), indicating a significant improvement in exercise capacity with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for the 6MWT is presented in Figure 17.

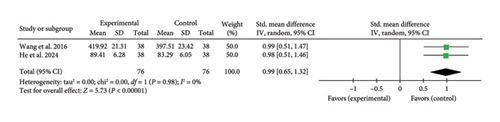

3.4.11. SAQ

Two studies [40, 44] reported a combined effect size for the SAQ (SMD = 0.99, 95% CI [0.65, 1.32], Z = 5.73, and p < 0.00001), indicating a significant improvement in SAQ scores with acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury cases. The forest plot for SAQ is presented in Figure 18.

3.5. Assessment of Publication Bias

No publication bias analysis was performed, as none of the included outcome indicators were supported by more than 10 studies.

3.6. Security

None of the 26 studies reported adverse effects associated with acupuncture therapy, suggesting a favorable safety profile for acupuncture in myocardial I/R injury.

3.7. Evaluation of Evidence Quality

Evidence quality, assessed using the GRADE system, ranged from moderate to very low. The incidence of MACE was rated as moderate quality, while AST, IL-2, IL-1, IL-8, LVESD, TCM chest pain symptom score, 6MWT, and SAQ were classified as low quality. The evidence for cTnI, CK-MB, CK, LDH, BNP, hs-CRP, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, MDA, SOD, LVEF, LVFS, LVEDD, LVEDV, LVESV, heartbeat recovery rate, ICU stay duration, and hospital stay duration was rated as very low quality, as detailed in Table 16.

| Outcome measures | Number of participants (number of studies) | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Inaccuracy | Publication bias | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cTnI | 1465 (8) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| CK-MB | 823 (5) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| CK | 180 (3) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| AST | 86 (1) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| LDH | 123 (2) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −2e | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| BNP | 461 (2) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| hs-CRP | 1240 (7) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| TNF-α | 364 (4) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| IL-10 | 458 (5) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| IL-6 | 1232 (7) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| IL-2 | 60 (1) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| IL-1 | 200 (1) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| IL-8 | 48 (1) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| MDA | 526 (5) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| SOD | 366 (4) | −1a | −1b | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVEF | 1273 (8) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVFS | 612 (1) | −1a | −2c | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVEDD | 774 (3) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVEDV | 699 (2) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVESV | 699 (2) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| LVESD | 162 (2) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| Heartbeat recovery rate | 238 (3) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| TCM chest pain symptom score | 206 (3) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| Duration of ICU stay | 274 (5) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| Duration of hospital stay | 320 (4) | −1a | −2c | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low quality |

| Incidence of MACE | 492 (5) | −1a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate quality |

| 6MWT | 194 (3) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

| SAQ | 192 (2) | −1a | 0 | 0 | −1d | 0 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low quality |

- aMethod of assigning concealment is not described.

- b75% > I2 > 50%.

- cI2 ≥ 75%.

- dSample size < 400 or wide confidence intervals.

- eSample size < 400 with wide confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

Myocardial I/R injury is a contemporary pathological concept characterized by exacerbated myocardial tissue damage upon the restoration of blood flow to previously occluded coronary arteries. This process is intricately linked to postoperative complications associated with coronary angioplasty, coronary revascularization, and heart transplantation. In 1960, Jennings et al. [48] first reported in a canine myocardial ischemia model that ischemic myocardial tissue exhibits exacerbated necrotic damage following reperfusion. Subsequently, in 1985, Braunwald and Kloner [49] further refined the concept of “myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.” Clinically, myocardial I/R injury manifests in several forms: (1) myocardial stunning, also referred to as post-ischemic cardiac insufficiency, characterized by transient systolic and diastolic dysfunction postreperfusion; (2) reperfusion arrhythmias, including ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation; (3) microcirculatory disturbances, attributed to microvascular obstruction and myocardial hemorrhage; (4) the no-reflow phenomenon, marked by impaired or absent restoration of coronary blood flow postreperfusion therapy, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion; and (5) lethal myocardial reperfusion injury. Given the high incidence of myocardial reperfusion injury following cardiac surgery, effective strategies for its prevention and management remain a critical focus in acute myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery treatment. While the precise pathogenesis of myocardial I/R injury remains elusive, three key pathological mechanisms have been identified: energy metabolism dysregulation and calcium overload serve as primary triggers [50, 51], oxidative stress and inflammatory responses are indispensable contributors [52, 53], and various forms of cell death ultimately determine the cardiac outcome [54].

Acupuncture, a cornerstone of traditional Oriental medicine with a history spanning millennia, has gained recognition from the WHO for its therapeutic efficacy in 107 conditions [55], including cardiovascular disorders such as coronary artery disease, angina, hypertension, arrhythmia, chronic pulmonary heart disease, and cardiac insufficiency. Acupuncture offers several advantages in managing myocardial I/R injury. As a nonpharmacological intervention, it provides a safer and more cost-effective alternative without the risks of drug dependency or adverse effects. Moreover, acupuncture serves as a valuable tool for investigating cardiac function and the mechanisms underlying various therapeutic interventions. Experimental studies have demonstrated its capacity to modulate myocardial electrical activity, cardiovascular microcirculation, cytokine levels, epigenetic modifications, and central regulatory mechanisms, thereby enhancing cardiac function. Notably, acupuncture exerts cardioprotective effects in myocardial disorders associated with calcium overload, energy metabolism dysregulation, mitophagy, apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and related signaling pathways [56–61]. Systematic reviews of evidence-based experimental research further support electroacupuncture’s protective role in myocardial I/R injury animal models [62].

This study analyzed 26 clinical trials investigating acupuncture for myocardial I/R injury, encompassing 1948 patients. All trials, comprising 22 Chinese and four English publications, were conducted in China. The treatment group primarily received acupuncture and moxibustion, with 15 studies employing electroacupuncture, six using traditional acupuncture, and four utilizing transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation. In the control group, 18 studies applied nonacupuncture interventions, while four used sham electroacupuncture, one employed sham acupuncture, and three implemented sham transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation.