Challenges in Access to Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Encephalitis in Hospitals in Latin America and the Caribbean

Abstract

This study is aimed at determining the characteristics of access to diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune encephalitis (AE) in hospitals in Latin America and the Caribbean. The descriptive, prospective, and multicenter study was conducted from October to November 2023. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages in the descriptive analysis, whereas measures of central tendency and dispersion were shown for quantitative data. A distribution map was created based on the number of participating countries. A total of 108 doctors from 19 Latin America and the Caribbean participated, and participants’ median age and years of medical practice were 40 and 13 years, respectively. Regarding specialties, individuals who responded the most to the survey were general intensivists (31.5%), neurologists (28.7%), and neurointensivists (17.6%). There were significant limitations in access to diagnostic methods (resonance, antibody testing, and electroencephalogram), absence of institutional protocols, potential high out-of-pocket costs in financing antibody tests, and low patient follow-up. Heterogeneous diagnostic strategies and therapeutic approaches were found in the countries evaluated, and there was acceptable access to first-line immunotherapy and anticrisis. This first multinational study addressing the existing limitations in Latin America and the Caribbean for treating patients with AE revealed great difficulties and possible inequities. It is important to conduct multidisciplinary collaborations to increase awareness of this disease among decision-makers, clinicians, and investors to reduce its negative impact on the well-being and productivity of affected populations.

1. Introduction

Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) is a spectrum of autoimmune diseases that cause inflammation of the brain tissue associated with neurological dysfunction [1]. The prevalence of AE is estimated at 13.7/100,000, and it is one of the main causes of encephalitis of noninfectious etiology [2].

One of the main limitations in determining the prevalence of AE in Latin America is the absence of diagnostic tests in most hospitals, hindering timely diagnosis [3]. In 2016, Graus et al. published diagnostic criteria to possibly detect AE according to clinical symptoms and complementary findings without the need to test for specific antibodies [4]. Diagnostic and therapeutic management must be adapted to the availability and response capacity of hospitals in low- and middle-income countries and regions [5].

First-line treatment involves immunosuppressive treatment, such as administering methylprednisolone, immunoglobulin, or plasma exchange. If there is no evidence of improvement due to the persistence of symptoms, treatment should be changed, and cyclophosphamide or rituximab should be started as second-line therapeutic strategies. Therapeutic failure or delay in starting immunosuppressive treatment is an indicator of poor functional prognosis [6]. It must be highlighted that 70%–80% of cases of AE respond satisfactorily to first-line treatment, and it is known that many therapeutic options are not available in Latin American countries, so this could affect the care of patients with AE [7–9].

AE should be considered in the presence of suggestive clinical symptoms after ruling out other secondary causes. Lack of access to diagnostic tests and treatment at Latin American hospital facilities delays adequate management and reduces the prevalence of this condition in this region [10]. A comprehensive approach to highly disabling neurological diseases is a priority in low- and middle-income countries to protect brain health and its connection with the human and economic development of these regions of the world [11]. This article is aimed at describing the characteristics of access to diagnosis and treatment of AE in hospitals in Latin America and the Caribbean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A descriptive, survey-based cross-sectional and multicenter study was conducted to determine the characteristics of access to diagnosis and treatment of AE in Latin American and Caribbean countries. The study was carried out from October to November 2023.

2.2. Population and Sample

This study was conducted through the REAL LABIC project, which includes all medical professionals involved in the care of patients with AE in Latin America and the Caribbean. Its main objective was to understand the different aspects of AE in our region, especially its epidemiology, clinical characterization, and management [12]. Once the participating centers were selected, a specialty doctor in charge of providing information on the strengths and weaknesses in AE diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up at their hospital acted as a representative. The physician representing the center was selected through a prior interview with the center’s participants as part of the REAL LABIC project. Following a training process on the key variables of the study, participants chose their representative, considering that the selected individual had to be responsible for the care of patients with AE. The sample size was not calculated for this study since we used the entire sampling frame available for a census study.

2.3. Instruments and Variables

A questionnaire was created using Google Forms and distributed to each selected participant, where relevant information was collected such as characteristics of the specialty (age, years of clinical practice, specialty, age group management in patients with AE, number of patients with AE treated, and type of hospital); access to diagnosis (type of electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring performed, neuroimaging available at their center, processing of autoantibodies at their hospital, processing time for antibodies, assuming costs of antibody testing for AE, and expected time to evaluate response to treatment in AE); and the treatment and management of encephalitis (initiation of AE treatment, maintenance therapy used, use of prednisone after initial treatment, use of protocol for management, training in management, and reasons for starting management).

2.4. Statistical Aspects

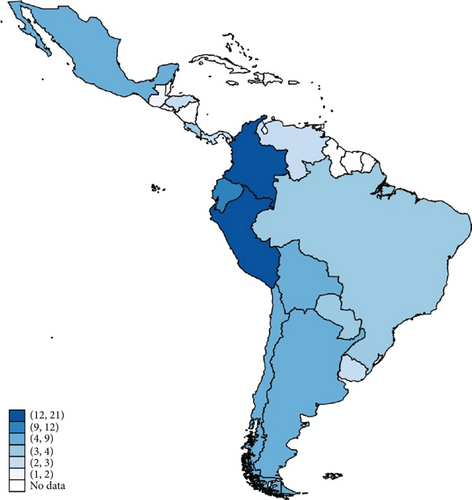

Data were stored in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, subsequently imported, and analyzed using the statistical program STATA v16.0 (Stata Corp, Texas, United States). In the descriptive analysis, categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion are shown for quantitative data. Based on the number of participating countries, a distribution map was created (Figure 1).

2.5. Ethical Aspects

This research study had ethical approval from the project “Disparities in access to diagnosis and treatment of AE in Latin American hospitals” prior to its execution, with university research registration (315-CEI-EPM-UCV-2023). No personal patient data were used to carry out the study, and no sensitive information was involved in patient management; however, the health personnel provided us with routine information on the diagnosis and treatment of AE at their hospital centers.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Participants

A total of 108 physicians participated, representing 19 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 1). Participants’ median age and years of medical practice were 40 and 13 years, respectively. Regarding specialties, individuals who responded the most to the survey were general intensivists (31.5%), neurologists (28.7%), and neurointensivists (17.6%). A little over half of the participants worked in public centers (55.6%) and three-fourths of all centers were university hospitals. The majority of respondents (65.1%) identified neurology as the specialty responsible for managing patients diagnosed with AE. Most respondents had experience managing cases of AE in adults (76.9%). Regarding the number of patients evaluated and managed by participating doctors, 54.2% had at least experience managing between 1 and 5 patients, and only 6.5% of those who responded to the survey had managed more than 20 patients (Table 1).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age+ | 40 (35–50.5) |

| Years of practice+ | 13 (7–23) |

| Select your specialty | |

| PhD physiotherapist intensivist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Immunologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Intensivist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Pediatric intensivist | 8 (7.4%) |

| Neurosurgeon | 1 (0.9%) |

| Neurointensivist neurologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Neurology resident | 1 (0.9%) |

| General intensivist | 34 (31.5%) |

| Neurocritical intensivist | 19 (17.6%) |

| Internal medicine | 1 (0.9%) |

| Neuroimmunologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Neurologists | 31 (28.7%) |

| Pediatric neurologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Pediatrician | 7 (6.5%) |

| Select the specialty that guides the management of patients with autoimmune encephalitis (AE) | |

| Pediatric immunologist/neurologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Main and multidisciplinary pediatric intensivist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Pediatric intensivist | 2 (1.9%) |

| General intensivist | 6 (5.7%) |

| Neurocritical intensivist | 9 (8.5%) |

| Internal medicine | 1 (0.9%) |

| Neuroimmunologist | 1 (0.9%) |

| Adult neurologist | 69 (65.1%) |

| Pediatric neurologist | 10 (9.4%) |

| Pediatrician | 6 (5.7%) |

| You have managed cases of AE corresponding to the following age group | |

| Adult | 83 (76.9%) |

| Both | 4 (3.7%) |

| Pediatric | 21 (19.4%) |

| How many patients are diagnosed with probable or confirmed AE? | |

| 1–5 | 58 (54.2%) |

| 11–20 | 17 (15.9%) |

| 6–10 | 25 (23.4%) |

| > 20 patients | 7 (6.5%) |

| Your hospital is: | |

| Mixed | 10 (9.3%) |

| Private | 38 (35.2%) |

| Public | 60 (55.6%) |

| Is your hospital a university hospital? | |

| No | 29 (26.9%) |

| Yes | 79 (73.1%) |

- +Presented as median and interquartile range.

3.2. Access to AE Diagnosis in Latin America and the Caribbean

Among those surveyed, 84.3% had access to at least one modality of EEG (continuous or quantitative EEG), and 15.7% did not have access to EEG methods. All hospitals evaluated had at least one neuroimaging modality, 82.5% had access to contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and 17.6% had access to contrast-enhanced tomography. Approximately 15% could perform positron emission tomography. All evaluated hospitals had access to performing lumbar punctures and the corresponding tests (cell count, protein levels, oligoclonal bands, and microbiological testing). Out of the hospitals included, 72.7% did not process antibodies in serum and/or cerebrospinal fluid; however, in 36.1% of cases, antibodies were processed nationally, and 23.1% of the tests were processed in laboratories outside the country where the samples were collected. The processing time was between 1 and 20 days in 78.7% of patients and > 20 days in 21.3%. Only 3.7% of tests took 30 days to report the results. The costs for conducting the tests were paid by the patient in 44.4% of cases and in 31.5% of cases by the health system. The remaining 24.1% were paid by private insurers, the laboratory, the hospital, or co-financed (Table 2).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| What type of electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring do you perform on your patient? | |

| Both | 3 (2.8%) |

| Continuous EEG | 26 (24.1%) |

| Quantitative EEG | 42 (38.9%) |

| Both | 20 (18.5%) |

| Does not have access | 17 (15.7%) |

| What neuroimaging can perform on your patients for AE? | |

| Simple and/or contrasted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | 29 (26.9%) |

| Simple and/or contrasted brain MRI, positron emission tomography (PET) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Simple and/or contrasted tomography of the skull | 19 (17.6%) |

| Simple and/or contrasted tomography of the skull, simple and/or contrasted brain MRI | 43 (39.8%) |

| Simple and/or contrasted tomography of the skull, simple and/or contrasted brain MRI, PET | 15 (13.9%) |

| Does your hospital process autoantibodies for AE? | |

| No | 78 (72.2%) |

| Yes | 30 (27.8%) |

| If you send the tests to another hospital/laboratory, please select where you send them: | |

| Hospital/laboratory in the same country | 39 (36.1%) |

| Hospital/laboratory in the same city | 35 (32.4%) |

| Hospital/laboratory outside the country | 25 (23.1%) |

| My hospital does the processing | 9 (8.3%) |

| Where are the tests sent to other hospitals and laboratories in your country processed? | |

| At the same receiving hospital/laboratory | 35 (32.4%) |

| They send the sample to an external foreign laboratory | 38 (35.2%) |

| They send the sample to an external national laboratory | 27 (25.0%) |

| My hospital processes the tests | 8 (7.4%) |

| Please indicate the range of time necessary for processing the antibodies: | |

| 1–15 days | 1 (0.9%) |

| 1–5 days | 13 (12.0%) |

| 11–20 days | 34 (31.5%) |

| 21–30 days | 19 (17.6%) |

| 6–10 days | 37 (34.3%) |

| > 30 days | 4 (3.7%) |

| Who assumes the cost of taking antibodies for immune-mediated encephalitis? | |

| Patient insurer | 1 (0.9%) |

| Private patient insurer | 16 (14.8%) |

| Co-financed | 4 (3.7%) |

| Laboratory | 2 (1.9%) |

| Patient | 48 (44.4%) |

| National/regional/local public health system or social security | 34 (31.5%) |

| Hospital’s own income | 2 (1.9%) |

3.3. Access to Treatment and Management of AE in Latin America and the Caribbean

Regarding respondents’ preference for the initial treatment, 52.3% preferred using methylprednisolone as the only treatment and 27.1% used dual therapy as initial therapy in cases of AE. If there was a lack of therapeutic response to the initial treatment, 43.9% added another first-line agent and 36.4% escalated to second-line therapy with rituximab. Regarding the occasional use of a third-line therapy, 16.6% used at least one agent; the drugs of choice being tocilizumab (15.7%) and bortezomib were used in only one case.

In terms of maintenance therapy, one-fifth of the participants did not specify the one used, and the rest, when indicated, preferably used prednisone (49.5%), rituximab (17.8%), and monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (6.5%). Regarding prednisone bridging therapy after first-line treatment, 53.3% of participants used it if the first-line treatment included methylprednisolone, and 19.6% indicated it even if it had not. Furthermore, 85.2% of participants started initial treatment within the first 10 days of patients’ admission. Regarding the delay in starting treatment, most participants mentioned initial suspicion of another disease (44.4%) or nonavailability of antibodies at their hospital (27.8%). Additionally, regarding the approximate number of patients with AE estimated to have continued outpatient follow-up by a specialist, most participants (39.8%) estimated that less than 10% of patients had follow-up.

Moreover, regarding whether their hospital has a written protocol for managing patients with AE, 89.8% did not have one, and 70.8% of participants had not received any institutional refresher course on managing this condition (Table 3). Finally, as for the drugs used to control epileptic seizures or status epilepticus, those with the greatest availability were propofol (97.1%), intravenous phenytoin or oral valproate (96.3%), and midazolam (96.2%) (Table 4).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| In the case of probable AE, you preferably start: | |

| Combination of two first-line treatments (dual treatment) | 29 (27.1%) |

| Immunoglobulin | 17 (15.9%) |

| Methylprednisolone | 56 (52.3%) |

| Plasma exchange | 5 (4.7%) |

| In case of step-up to new therapies after the initial regimen, you use: | |

| Continue pulse corticosteroids | 1 (0.9%) |

| Immunoglobulin | 1 (0.9%) |

| Immunoglobulin + methylprednisolone then rituximab | 1 (0.9%) |

| Plasmapheresis | 1 (0.9%) |

| Add another frontline agent | 47 (43.9%) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 14 (13.1%) |

| Repeat initial treatment | 3 (2.8%) |

| Rituximab | 39 (36.4%) |

| Do any of the cases require the use of any third strategy? | |

| Bortezimib | 1 (0.9%) |

| None | 86 (79.6%) |

| We do not have these | 2 (1.9%) |

| Rituximab | 1 (0.9%) |

| Rituximab/cyclofosfamide | 1 (0.9%) |

| Tocilizumab | 17 (15.7%) |

| Do you use maintenance therapy and, if so, what agents do you prefer? | |

| Azathioprine | 1 (0.9%) |

| Azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil | 1 (0.9%) |

| Mycophenolate | 1 (0.9%) |

| We do not have follow-up of posthospitalization patients | 1 (0.9%) |

| Prednisolone or rituximab | 1 (0.9%) |

| Monthly immunoglobulin | 7 (6.5%) |

| Monthly methylprednisolone | 1 (0.9%) |

| Not indicated | 21 (19.6%) |

| Prednisone | 53 (49.5%) |

| Rituximab | 19 (17.8%) |

| Do you use prednisone bridging therapy after initial treatment? | |

| Not indicated | 29 (27.1%) |

| Indicated, even though methylprednisolone was not used | 21 (19.6%) |

| Indicated, only if methylprednisolone was used | 57 (53.3%) |

| Please select the expected time to evaluate response and escalation to new therapy. | |

| 24–72 h | 29 (26.9%) |

| 4–7 days | 56 (51.9%) |

| 8–13 days | 7 (6.5%) |

| 14–28 days | 13 (12.0%) |

| Is there a written protocol at your hospital for the management of patients with AE? | |

| No | 97 (89.8%) |

| Yes | 11 (10.2%) |

| Have you received any updated courses or academic activity in the diagnosis of AE? | |

| No | 75 (70.8%) |

| Yes | 31 (29.2%) |

| How long does it usually take to start immunomodulatory treatment from the patient’s admission? | |

| 1–15 days | 1 (0.9%) |

| 1–5 days | 53 (49.1%) |

| 11–20 days | 8 (7.4%) |

| 21–30 days | 6 (5.6%) |

| 6–10 days | 39 (36.1%) |

| > 30 days | 1 (0.9%) |

| Reasons for delay in treatment start time | |

| Lack of availability of medicines | 9 (8.3%) |

| Admission to hospitalization for non-neurological care (psychiatry, internal medicine, or others) | 10 (9.3%) |

| Most of the time, treatment begins before the antibody result appears | 1 (0.9%) |

| Unavailability of autoantibodies | 30 (27.8%) |

| There are no such problems | 1 (0.9%) |

| Delay in obtaining results | 1 (0.9%) |

| Suspected encephalitis infection/Systemic infection | 1 (0.9%) |

| Initial suspicion of another entity (infectious, systemic disease, etc.) | 48 (44.4%) |

| All, except the critical situation of the patient or hospital admission for nonneurological care | 1 (0.9%) |

| We try to make it as quick as possible | 1 (0.9%) |

| Several causes, from late diagnosis, lack of medications, and lack of diagnostic tests | 1 (0.9%) |

| Lack of availability of auxiliary exams at the center | 1 (0.9%) |

| Critical patient situation | 3 (2.8%) |

| What approximate percentage of patients with AE do you consider for continuing an outpatient basis? | |

| 10%–50% | 27 (25.0%) |

| 51%–90% | 16 (14.8%) |

| They are usually sent to other sites for follow-up | 1 (0.9%) |

| > 90% | 11 (10.2%) |

| < 10% | 43 (39.8%) |

| Does not know | 10 (9.3%) |

| Medication | No | Occasionally | Yes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral levetiracetam | 5 (4.6%) | 4 (3.7%) | 99 (91.7%) |

| Intravenous levetiracetam | 37 (34.6%) | 9 (8.4%) | 61 (57.0%) |

| Oral phenytoin | 11 (10.3%) | 3 (2.8%) | 93 (86.9%) |

| Intravenous phenytoin | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 104 (96.3%) |

| Oral valproic acid | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 104 (96.3%) |

| Intravenous valproic acid | 53 (49.1%) | 8 (7.4%) | 47 (43.5%) |

| Oral lacosamide | 42 (39.3%) | 5 (4.7%) | 60 (56.1%) |

| Intravenous lacosamide | 76 (71.7%) | 4 (3.8%) | 26 (24.5%) |

| Oral phenobarbital | 25 (23.4%) | 11 (10.3%) | 71 (66.4%) |

| Intravenous phenobarbital | 34 (32.7%) | 11 (10.6%) | 59 (56.7%) |

| Oral topiramate | 27 (25.5%) | 7 (6.6%) | 72 (67.9%) |

| Oral lamotrigine | 14 (13.3%) | 6 (5.7%) | 85 (81.0%) |

| Oral carbamazepine | 8 (7.5%) | 1 (0.9%) | 97 (91.5%) |

| Oral oxcarbazepine | 46 (43.8%) | 6 (5.7%) | 53 (50.5%) |

| Intravenous propofol | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.9%) | 101 (97.1%) |

| Intravenous thiopental | 29 (28.2%) | 7 (6.8%) | 67 (65.0%) |

| Intravenous ketamine | 16 (15.4%) | 8 (7.7%) | 80 (76.9%) |

| Intravenous pentobarbital | 54 (52.4%) | 10 (9.7%) | 39 (37.9%) |

| Intravenous diazepam | 4 (3.8%) | 3 (2.8%) | 99 (93.4%) |

| Intravenous midazolam | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 101 (96.2%) |

| Intravenous lorazepam | 73 (69.5%) | 7 (6.7%) | 25 (23.8%) |

4. Discussion

This study is aimed at describing the characteristics of access to diagnosis and treatment of patients with AE in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Important limitations were evident in access to diagnostic methods (MRI, antibody testing, and EEG), absence of institutional protocols, potential high out-of-pocket costs in financing antibody tests, poor follow-up of patients, deficiencies in the university training of general practitioners and specialists, and in continuing medical education. Furthermore, heterogeneity was evident in diagnostic strategies, escalation times, and therapeutic modalities in the countries evaluated. There is potential harm to the health and life of patients with AE due to the features described in Latin America and the Caribbean. It was also possible to confirm acceptable access to first-line immunotherapy and antiseizure, a multidisciplinary treatment led by the neurology (adults and pediatrics) and intensive care (general and neurocritical) units. Human talent emerged as the main asset to respond to the needs imposed by AE in the countries within this region.

4.1. Diagnosis and Access to Auxiliary Studies

The diagnosis of AE is challenging for clinicians because of the different clinical conditions that can present with similar symptoms (especially infectious encephalitis in tropical climates) and the availability of adequate diagnostic methods [13]. Therefore, a diagnosis based on the combination of a detailed clinical history, exhaustive physical and neurological examinations, and appropriate use of diagnostic aids is very important. The criteria for the diagnosis of AE published in 2016 [4] establish the framework for an accurate diagnosis and include performing brain MRI, cerebrospinal fluid studies, EEG, measurement of neural autoantibodies, and, in selected cases, the search for primary tumors. In our investigation, access to brain MRI was 82.5%. This suggests that one in five hospitals evaluated does not have access to this imaging modality. In all cases, however, there is access to simple and contrast-enhanced tomography, the usefulness of which is very limited in this context but helpful in some differential diagnoses. Positron emission tomography is available in 15% of health care centers, and its usefulness in AE is increasingly being described. It can show earlier changes than MRI, have greater sensitivity in early stages, and can help search for related tumors [14]. Therefore, there is universal access to neuroimaging at the centers studied, but there are limitations in performing brain MRI and positron emission tomography according to the currently available recommendations [15, 16].

The timely measurement of antineural antibodies in suspected patients from the environment studied was poor, and significant difficulties were experienced. Only 27.8% of the centers evaluated were able to perform the test at their institution. The methods for conducting this measurement consisted of sending the sample to laboratories within the same country (68.5%) or abroad (23.1%). One in five hospitals reported more than 20 days between test collection and results, and a considerable minority (27%) of respondents delayed treatment until antibody results were available, suggesting that treatment may be delayed in some cases due to delays in antibody testing results. Previous investigations in our region show low availability of antibody testing, delays in treatment, higher mortality, and associated sequelae [17, 18]. The difficulties in our study have been widely described in other studies and reports, specifically in Brazil, through the Brazilian Autoimmune Encephalitis Network [19].

One of the most significant barriers found in our study was poor accessibility to funding for antineural autoantibody testing. It is concerning that 44.4% of patients had to bear the test cost. Previous reports estimate costs between 300 and 900 US dollars, constituting one and three times the minimum monthly income in the regions evaluated [20, 21]. Public health systems assume this cost in 31.5% of the centers evaluated; however, in cases like Colombia, only the dosage of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antibodies is covered [22]. The availability of antibody tests in other low-income regions of the world has been paid for by private laboratories or the patient in most cases [20]. In our investigation, private laboratories and hospital financing represented only 3.8% of the sources. Out-of-pocket spending on health represents inequity and a perpetuator of the cycle of poverty and disease, especially in low- and middle-income areas [23].

EEG studies are suggested in international guidelines for studying patients with AE [15, 16]. Their usefulness lies in the fact that they can identify focal abnormalities with normal MRI results, help diagnose specific types of AE, and are, for example, part of the diagnostic criteria for limbic encephalitis. The most common findings are nonspecific (slowing and focal discharges). Extreme delta-brush is seen in 30% of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis and other specific types. In our investigation, 84.3% of participants had access to at least one modality of EEG (continuous or quantitative EEG). Thus, we consider that, although most centers having the power to perform EEG studies is a strength, the fact that 15% of hospitals did not have the possibility of performing any type of EEG is critical and represents an additional challenge to managing the complexity of this disease.

4.2. Treatment and Clinical Follow-Up Protocols

It was evident that most participants in our study reported not having institutional protocols (89.8%) and had not received any academic training from their institutions (70.8%). This is something important that must be reinforced in hospitals in low- and middle-income countries, where the availability of tests and treatment is limited since an incorrect diagnosis of AE can increase morbidity due to unnecessary immunotherapy and delay the proper management of these patients [24]. Furthermore, it was reported that most participants started treatment < 10 days after the patient’s admission to start some immunosuppressive treatment and < 7 days to indicate treatment escalation in case of lack of therapeutic response. This finding denotes the importance given to AE when it is suspected since timely diagnosis and treatment are associated with a better functional prognosis. However, international good practice recommendations indicate that the exact time to evaluate therapeutic response is poorly defined [25].

Regarding access to treatment, most participants could access first-line immunosuppressive treatment, and there was growing access to second-line therapies. However, it is important to mention that in some countries, certain drugs, such as immunoglobulin or rituximab, are not regulated or available as a therapeutic option [8], although there is some evidence in patients with some types of AE. Also, immunoglobulin is one of the most used first-line agents, and rituximab is the second-line agent most used in other countries with an adequate level of efficacy and safety [25–29].

Methylprednisolone was reported to be the preferred agent for most participants. However, a trend was also seen toward the use of first-line combination therapy as a first intention or as step-up therapy in the event of failure of the use of a first-line first agent. This is recommended in cases of AE considered severe (NMDAR and severe dysautonomia) [25]. Furthermore, 79.6% reported not requiring third-line treatment, which could reflect the effectiveness of first- and second-line agents for managing patients with AE.

There was heterogeneity in the indication for maintenance treatment, with corticosteroid therapy, rituximab, and immunoglobulin being the most used therapeutic agents. The preferred use of prednisone as bridging therapy among the survey participants was remarkable, and it has been previously reported as bridging immunotherapy to discharge [30]. Likewise, there was also heterogeneity in the availability of the use of antiseizure medications, but most centers had the availability of at least one intravenous medication and one oral medication for seizure control in these patients. This is important because epileptic seizures are one of the main clinical manifestations of AE and are the reason for admission to critical care units [31].

Regarding clinical follow-up, only 10% of participants reported outpatient follow-up of treated patients diagnosed with AE. Follow-up of these patients after the initial episode is as important as the treatment in the acute phase of the disease since it is widely known that a percentage of patients can relapse. The appearance of neoplasms in the future, or physical and neuropsychological sequelae, has also been reported [30]. In our setting, cognitive sequelae have been described in > 90% of patients beyond 1 year of follow-up [32, 33].

4.3. Continuing Medical Education

Despite an average experience of 13 years among the personnel evaluated, the majority (93.5%) had treated < 20 patients with AE. This suggests that, on average, three patients are seen over 2 years. This is consistent with the incidence of the disease and the absence of specialized centers for these patients, which generate geographic dispersion for treatment. University education and continuing medical training are of major importance in this scenario of low exposure to real patients. However, despite having 73% of university hospitals among those evaluated, 70% of the personnel had not received training courses in AE from their institutions in the last year. Additionally, strikingly, < 1% of those evaluated had specialized training in neuroimmunology, and therefore, the presence of subspecialized medicine does not make up for the training deficiencies of the basic specialties. Therefore, a greater presence of specialized medicine in areas of neuroimmunology is required, as well as greater training in basic interdisciplinary specialties in charge of patients with AE in our environment. In the future, as Moeller et al. note, there will be an increase in emphasis on educational outcomes and the public impact of neurology training programs [34]. In summary, although AE requires specialized hospital infrastructure, training human talent is vital for environments with limited resources and growing concerns about cost-effectiveness and cost-usefulness for the design of public policies.

4.4. Future Perspectives

A recent bibliometric analysis showed how most publications on AE were conducted in high-income Western countries [35]. This creates a bias for the design of clinical protocols, specific recommendations, and public policy planning for the regions and their particularities not represented in these studies. Bhatia et al. provide recommendations to reduce the impact of these gaps, namely, improvement in training for the identification of classic syndromes as well as the red flags such as hyponatremia and cardiac arrhythmias, administration of empirical therapy in cases of high suspicion even without confirmation through serological or cerebrospinal fluid, and enhanced development of multidisciplinary protocols and policies given the reversibility of these entities and the performance of regional clinical studies [20].

4.5. Authors’ Recommendations to Improve Access to Patients With AE in Resource-Limited Settings

- ✓

Develop public policies for adequate access, treatment, and monitoring of patients with AE in brain healthcare.

- ✓

Strengthen formal education and continue medical education on issues concerning AE for general practitioners and specialties related to the care of these patients.

- ✓

Strengthen research networks to construct local data as a substrate for public policies.

- ✓

Implement protocols, guides, and homogeneous guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with AE in the region.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

Public and university institutions in > 15 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean participated, which provides a broad overview of the situation in the region. The study included many specialties involved in caring for patients with AE, providing a global and interdisciplinary perspective. Participants consisted of medical personnel directly involved in the care of these patients, with a high average of years of clinical practice and who worked in reference hospital centers in the different countries of the region studied.

Our study has several limitations. Regarding the respondents, this study reported that fewer than one-third were neurologists; however, neurology was identified as the specialty responsible for managing AE in nearly two-thirds of the surveyed hospitals. This may have influenced some of the results related to the number of AE patients treated by the respondents. This represents a limitation of the study and suggests that the inclusion of more neurologists might have provided a more accurate picture of how AE cases are managed. Since it was carried out through a survey, the results are exposed to memory and selection biases because the survey cannot reach all the actors involved. Given the absence of institutional protocols and scientific societies, the specialists in charge are heterogeneous and may have “school protocols” that affect the uniformity of the data. No information was obtained on the direct cost of antibody testing, nor was it possible to establish the techniques by which autoantibodies are measured in local laboratories (for example, cell-based assay, immunoblotting, radioimmunoassay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), and the importance of the technique used related to diagnostic performance is well known.

5. Conclusions

The report of this first multinational study that addresses the existing limitations in Latin America and the Caribbean regarding the care of patients with AE reveals great difficulties and possible inequities. The lack of organized, intersectoral, and comprehensive plans for the management of patients with AE in low- and middle-income countries can be detrimental to global brain health and its consequent impact on people’s well-being and economic growth. We suggest that all efforts and multidisciplinary collaborations be made to increase awareness of the disease among decision-makers, clinicians, and investors to reduce its negative impact on brain health and the well-being and productivity of populations. Future investigations are encouraged to clarify the epidemiological and clinical aspects of AE in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Miguel A. Vences and Julián A. Rivillas contributed equally.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The REAL LABIC Group consists of Saúl Reyes-Niño, Maricela García-Arellano, Donoband Melgarejo, Mary M. Araujo-Chumacero, Cintia Johnston, Mercedes A. Suárez-Loro, Stefany Espinoza-Ramon, Diego Canales–Pichen, Victor Saquisela, Jesús Angel Dominguez Rojas, Carla Gabriela Román Ojeda, William Bayona Pancorbo, Vanessa Cristina Godoy, Habib Moutran-Barroso, Carolina Velázquez, Marlene Romero, María Belen Gómez, Jorge Flecha, José Domingo Barrientos, Silvia Fabiola García Martínez, Maria Alejandra Gramajo Juárez, Ana Beatriz Sontay Chan, Miguel Angel Pelcastre Mejía, Karen Perales, Gustavo Domeniconi, Milagros García, Wilfor Aguirre, Oriani Moreno, Telmo Fernández, Marcos Teheran, Danilo Fischer, María Eugenia Vázquez, Sebastián Vásquez-García, Werther Brunow de Carvalho, Lucia Flores Lazo, Martha Gamez Blandon, Cristina Verdú Sánchez, Óscar Eduardo Sotelo, Diego Galindo Talavera, Paul Cardozo Gil, Sergio Rovira, Gonzalo Lacuesta Mendiondo, Viviana Sampietro Serafim, Oscar Cabrera, Lorena Acevedo, Gustavo Costales, Michele Luglio, Sofía Posadas Gutierrez, Alcides Díaz Claros, Rolando Cusimayta Soto, Angella Cabanillas Olivares, Luis Fermin Naranjo Atehortúa, Luisa Rueda Cardenas, Yesica Luna Delgado, Sandra Flores Irias, Jorge Gramajo, Sandra Rodríguez Guifarro, Julio Guevara Jiménez, Caridad de Dios Soler Morejón, Elvia Borges H, Julián Morejón Chávez, Nilcea Freire Nil, Walter Valverde, David Villegas, Walter Videtta, Juan Carlos Acuña Mamani, Yamirka Montesino Felipe, Frank Martos Benítez, Xiomara Mora De La Cruz, Luis E. Rodríguez, Carlos Alberto Gonzalez, and Miguel A. Barboza.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.