Beyond Bottles: Exploring Consumer Perceptions and Preferences for Bag-in-Box Wine Packaging

Abstract

The change in consumption habits, the need for product differentiation and the transition to eco-sustainable wine production have led to the adoption of alternative packaging solutions, moving beyond the traditional glass bottle. This study employs experimental auctions with a sample of 100 participants to assess consumer willingness to pay for both bag-in-box and traditional glass bottle packaging. Using statistical tests and regression analysis, we find that consumer preferences for wine packaging formats significantly influence purchasing decisions and perceptions of product quality. Notably, consumers show a lower willingness to pay for the same wine when packaged in a bag-in-box than a bottle, and taste does not influence the willingness to pay. Moreover, the preference for bottled wine seems to be socially influenced. This study enriches the understanding of consumer behaviour regarding packaging preferences and provides actionable insights for the wine industry, retailers, policymakers and consumers.

1. Introduction

The function of food and beverage packaging has undergone significant changes throughout history. Although it first serves for preservation and protection, packaging is an important marketing tool that allows producers to promote their business and enhance their brand [1]. Moreover, it can help define and contextualise the product and the occasion for its consumption, portioning, recognisability and environmental sustainability. Growing consumer attention towards sustainability significantly impacts business choices in terms of packaging, steering them towards materials that are more environmentally respectful. There are various packaging types, offering more or less sustainable impacts both in the production phase, by saving inputs and energy, and in the transportation and distribution phase, by limiting CO2 emissions, and finally, in the postuse material recovery and recycling phase [2, 3].

This issue is particularly relevant in the wine sector, where evolving tastes and consumer preferences are reflected in packaging choices. While the traditional glass bottle remains the most popular format [4], there has been a growing trend towards lighter and more practical formats, such as cans and the bag-in-box, especially popular among younger consumers seeking convenient, environmentally friendly wine consumption solutions [5, 6]. This alternative wine packaging has better performance in terms of environmental impact [7, 8], and the bag-in-box can offer a significant alternative for wineries. Despite its lower production costs and environmental impact compared to glass bottles, there are contrasting consumer attitudes towards this format.

The bag-in-box format has experienced significant growth in organised large-scale retail in recent years [9], especially during the COVID-19 pandemic [10]. During this time, there was an increase in the number of meals consumed at home and a shift towards purchasing large, easily transportable products to minimise shopping trips due to fear of contagion [11, 12]. In this context, the bag-in-box, with its suitability for daily wine consumption, may have appeared as one of the most convenient options. However, some researchers have pointed out that it is entirely ignored by German consumers who show a high involvement in wine [13] and that 91% of Italian consumers were unwilling to change their wine purchasing habits, preferring glass bottles exclusively [14], which remains the best material for preserving wine’s chemical and organoleptic characteristics [4].

-

Rq1: Does the format impact the consumer’s WTP in daily wine consumption?

-

Rq2: Does the perceived taste change for a wine for everyday use when it is bottled compared to a bag-in-box?

-

Rq3: Does the WTP for bottled or bag-in-box wines for everyday consumption depend on the perception of taste?

-

Rq4: Does organic certification affect the WTP for a bag-in-box wine?

-

Rq5: Do sociodemographic and attitudinal factors affect the WTP for wine packaged in bottle and bag-in-box?

To answer these research questions, we developed an experimental auction involving 100 Italian bag-in-box wine consumers. Given the absence of official statistics about the sociodemographic structure of Italian bag-in-box wine consumers, participant recruitment for the auction was preceded by a pilot study on a representative sample of Italian wine consumers to define the sociodemographic characteristics of those who consume this product also in the bag-in-box format.

After introducing and explaining the research questions, this article is structured into two paragraphs that report the state-of-the-art studies published so far on packaging in the wine sector and on consumers’ WTP for these. A description of the methodology used in the case study and how the representative sample was defined, and the questionnaire administered follow. Subsequently, the results obtained from analysing the questionnaire and auction information, which were used to answer the five research questions, are illustrated. Finally, we comment on the results of our study relative to the scenario outlined in the literature review and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Packaging in the Wine Industry

The choice of packaging type for winemakers depends on multiple factors, such as the type of wine, current regulations and consumer demand and preferences. The primary role of packaging is to protect and preserve wine from external alterations and damage. However, today, packaging also has a marketing function, being an essential component of the integrated marketing strategies of the food industry [22]. During the purchasing process, the first interaction consumers have with a product is with its package, which provides significant information about the product it contains and strengthens associations with it. This seems particularly true for wine; since consumers cannot taste it or evaluate its taste and flavours before purchasing, they have to choose wine using the available visual elements such as packaging, format, label and other attributes [23]. Consequently, for consumers, packaging becomes a driver of choice for wine and affects the perception of its quality [24, 25]. Moreover, packaging can also serve as a means for product differentiation, allowing it to stand out from competitor products [1].

Despite the large number of packaging alternatives currently available, not all types of wine are suitable for the various packaging options. For instance, packaging other than the glass bottle might not be suitable for a high-quality wine that requires a long period of ageing before opening. Indeed, numerous studies [26–28] have shown that over time, packaging can influence the organoleptic qualities of wine and their evolution. In general, the glass bottle preserves the wine from the deterioration of sensory characteristics for a longer period compared to packaging options such as PET bottles or bag-in-box. Ghidossi et al. [26] carried out chemical analyses on wines twelve months after packaging and they found greater oxidation and loss of aromatic intensity in bag-in-box wines compared to those packaged in glass bottles. Furthermore, even though the quality was acceptable, after just 3 months, the tasting panel perceived the bag-in-box wines as much more mature and oxidised compared to the bottled wines [27, 28]. After 6 months, the quality of bag-in-box wines was perceived as inferior compared to that of wines in glass bottles [29]. This deterioration of the wine can be due to the absorption of volatile compounds by the plastic materials some packaging alternatives are made of and, for bag-in-box, also from wine lost in the environment through leakage of the valve [27].

The choice of packaging must also comply with the regulatory framework governing the wine sector. In Italy (where this study was conducted), the current legislation (Italian Legislative Decree No. 61 of 8 April 2010; Decree of the Minister of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies of 13 August 2012) does not present particular restrictions on the use of packaging alternatives for Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) wines, while for Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) wines, the decree establishes differentiated rules for Controlled Designation of Origin (DOC) and Controlled and Guaranteed Designation of Origin (DOCG) wines.1 DOCG wines must be marketed in bottles, unlike DOC wines where other types of packaging are also allowed. However, for DOC wines, this is permitted if the name of the DOC is not combined with specific additional terms, such as a geographical unit or a subzone. In addition, the specific production specifications of each PDO wine can establish more stringent constraints compared to national legislation. For example, while Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC red wine can be sold in bag-in-box, the production specification of Rosso di Montalcino DOC red wine prohibits the use of containers other than glass bottles.

If standard glass bottles have long been the traditional packaging for wine, consumers can find several alternatives on the market. A recent study by Orlowski, Lefebvre and Back [30] found that consumers perceive non-traditional packaging as less attractive, which, in turn, negatively influences consumer expectations in terms of taste and their intention to buy. Italian consumers consider the wine bottle the most suitable packaging for wine and are not interested in buying wine in packaging alternatives [14, 31]. For wine, alternative and innovative packaging such as PET bottles, cans or lightweight glass bottles have been rated negatively by consumers [32]. Capitello et al. [33] highlighted that most consumers doubt the suitability of a bag-in-box to contain quality wine. Ruggeri et al. [31] emphasised that consumers perceive wine in cans as a low-quality product. Resistance in the Italian market to these packaging alternatives can be explained by the lesser familiarity that most consumers have with them [30], especially in the so-called ‘Old World wine’ countries where the glass bottle seems to be perceived as the most traditional container.

Packaging alternatives for wine have objective advantages that are recognised by consumers. For instance, the structure and composition of the bag-in-box allow for low oxygen permeability [34], which helps in preserving the wine for more days even after opening it [7, 35]. This makes the bag-in-box packaging particularly suitable for consumers who only want to drink a glass of wine during meals and who do not want to worry about finishing the bottle within a few days. Moreover, consumers recognise the convenience of this packaging in terms of ease of transport, storage and use [33, 35]. When purchasing, the bag-in-box increases consumer productivity in terms of time and money because, for the same volume, consumers spend less time choosing a bag-in-box instead of bottles and also spend less [36]. Then, since glass is more fragile than a carton, the bag-in-box is safer in terms of reducing the risk of breakage, especially during transport.

Recently, consumers are increasingly aware of the environmental impact of their actions, including their purchasing and consumption behaviours [37, 38]. In this sense, the different types of packaging and the materials they are made of influence consumer perception in terms of environmental sustainability. In general, consumers consider glass as the ‘greenest’ material along with paper-based packaging alternatives, unlike plastic and metals which are seen as having the most negative environmental impact [39, 40]. De Feo, Ferrara and Minichini [41] confirmed these results for beverage packaging. Considering beer and soda packaging, Boesen, Bey and Niero [39] highlighted that consumers perceive PET bottles and aluminium cans as nonsustainable packaging. However, among glass bottles, consumers classify disposable bottles as non–eco-friendly, unlike reusable ones. These perceptions seem to be affected by the fact that consumers associate environmental sustainability exclusively with the packaging recyclability, without considering its production process and the impact of transportation [39]. As highlighted by Ferrara et al. [42], glass bottles, with a higher recycling rate, represent the least sustainable packaging due to the high consumption of resources and energy in the production process. Considering the environmental impact of different beer packaging in terms of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) evaluation, Boesen, Bey and Niero [39] demonstrated that aluminium cans and PET bottles have half the impact compared to disposable glass bottles. The superior environmental performance of packaging alternatives has also been demonstrated for wine. Ferrara and De Feo [7] verified that disposable glass bottles are the least eco-friendly container, while the bag-in-box is the best alternative, with an impact that is 60%–90% lower than disposable glass bottles, followed by the carton. The superior environmental performances of the bag-in-box and carton are due to the lower incidence, for the same volume of wine, of the packaging weight, which translates into greater efficiency in distribution. The greater environmental sustainability of bag-in-box compared to glass also emerged in the study by Ponstein, Ghinoi and Steiner [8]. Investigating the environmental impact of wine in different types of packaging and imported into Finland from the eight main wine-producing countries, the bag-in-box was the packaging with the lowest level of greenhouse gas emissions, regardless of the country of origin.

Individual sociodemographic traits, psychological characteristics and consumption habits also play a role in consumer’s evaluation of packaging alternatives. Capitello et al. [33] highlighted that the likelihood of purchasing bag-in-box wine increases with age and with the frequency of wine consumption. However, packaging alternatives are increasingly attracting the attention of young wine consumers, as evidenced by Thach, Riewe and Camillo [5], according to whom consumers born after 1981 in the United States have a higher level of acceptance of wine in cans compared to elder consumers. Approval for wine in innovative packaging is also affected by the level of subjective involvement for wine [13]. Moreover, a driver affecting behaviour and purchasing preferences is the occasion of consumption, with wine packaging associated with specific occasions. In fact, consumers associate bag-in-box wine with everyday consumption or informal events, while the standard glass bottle is preferred for formal occasions [33, 43].

Considering packaging alternatives in relation to the sustainability of wine production, an important role has been covered in organic and biodynamic management. The literature reported that eco-certification (i.e., EU Organic, USDA and Demeter) is associated with the highest quality wines [44] although this perception is not consistently shared by consumers [20]. Compared to conventional wines, biodynamic ones have sometimes been reported as superior in quality [45, 46] or as having similar quality levels [47, 48]. However, very few articles indicate how different winemaking processes (conventional, organic and biodynamic) could affect the quality of the wine [49]. Recently, Maioli et al. [50] have conducted a study on conventional, organic and biodynamic DOCG wine with the aim of evaluating the perceived quality related to the wine production process. The results evidenced that despite differences found in terms of sensory attributes, such as astringency and bitterness more related to organic and biodynamic wines due to more evolved wines in terms of colour stability compared to the conventional ones, the quality of wine is independent of the management, and every type of it could achieve a high score for the perceived quality.

2.2. Packaging and WTP

Most studies of consumers’ wine packaging preferences rely on rating-based models, such as metric or semantic scales [13, 14, 30, 33]. Stanco, Lerro and Marotta [32] investigated consumer preferences for packaging alternatives by including these as attributes within a best–worst experiment and assessing their relevance compared to other choice attributes. However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have estimated WTP for different packaging alternatives implementing indirect methods such as choice experiments or experimental auctions. Some choice experiments have been applied to examine consumer preferences and WTP for specific packaging-related aspects, such as different bottle label styles [51, 52] or different bottle closures, such as screw caps and cork [53]. Drichoutis, Klonaris and Papoutsi [54] elicited WTP for a sweet wine bottled in different formats, namely, a 500-mL bottle and a 750-mL bottle, through an experimental auction. Ruggeri et al. [31] implemented a contingent valuation to study consumer WTP for wine in a 25-cL aluminium can. The first study to estimate consumer WTP considering different packaging alternatives was that by Naspetti et al. [55], which analysed a nonalcoholic sparkling wine offered in a glass bottle and in a can. A recent study by Mesidis et al. [6] has investigated Australian consumer preferences and WTP through a choice experiment considering different formats: traditional glass bottle, bag-in-box, flat PET bottle, carton and can. The results showed that bag-in-box and PET glass lookalikes hold the most promise although glass is still the preferred format. Indeed, while the entire sample analysed showed a positive WTP for the traditional glass bottle, there was a group of consumers that demanded a premium for wine in bag-in-box.

To our knowledge, the study by Mesidis et al. [6] is the first to deal with consumer preferences and their WTP for bag-in-box wine. However, the methodological approach developed in our work is based on a different technique of revealed preferences, the experimental auction. The main advantage of this nonhypothetical method is to involve individuals in an active market environment, where an actual exchange between the product and money occurs and where participants, therefore, face the real economic consequences for their responses [56, 57]. This method has significant advantages as it is incentive-compatible, and participants’ bids directly represent their WTP for the product [58]. Moreover, a nonhypothetical experiment avoids the effect of ‘hypothetical bias’, which leads to an overestimation of WTP [59]. Several studies have used the auction method to analyse consumer perceived value for specific wine characteristics, estimating WTP for different designations of origin [60–62], regions of origin [63, 64], producer name [65], blends made with different grapes [66], sulphite-free wine [67], local wine [68], awards received [69], bottle format [54], sparkling wine production method [70] and nutritional information [71].

Various auctions have been used to assess consumer WTP for claims or information regarding the environmental and social sustainability of the winemaking process [72–75], also evaluating the ‘organic wine’ claim [76–79]. Scozzafava et al. [15] estimated and statistically compared WTP for wines produced using different processes: conventional, organic and biodynamic. In some cases, the implemented experiments elicited the WTP for individual information treatments including tasting, thus associating preferences with taste evaluation [15, 62, 76, 77, 79].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The study was conducted in November 2022 in Italy and involved a sample of 100 individuals representative of gender and age of Italian wine consumers who are familiar with bag-in-box wines. To ensure the representativeness of the experiment’s results, a pilot study on a sample of 250 Italian red wine consumers representative of gender and age was carried out before the recruitment of the 100 auction participants by a company specialising in marketing research.2 Through an online questionnaire, sociodemographic information and knowledge and consumption of wines in various formats, including bag-in-box, were collected for this sample. Based on these data, it was then possible to identify the sociodemographic traits of those who know bag-in-box as a packaging format for wines, who accounted for only 51% of Italian wine consumers. The sociodemographic structure of the subsample resulting from the pilot study was used to recruit the 100 participants for the subsequent auction and is reported in Table 1.

| Italian wine consumers (ISTAT) (%) | Consumers who know bag-in-box wines (pilot study) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–45 | 32 | 36 |

| 46–65 | 39 | 40 |

| > 65 | 29 | 24 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58 | 67 |

| Female | 42 | 33 |

3.2. Products for Auction

The product chosen for this experiment was a Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC wine produced in 20213 by a single winemaker with organic certification. The selected winemaker uses the same wine for each vintage, varying only the format. This means that, originally, the wine contained in the bottle and in the bag-in-box has undergone the same production process, comes from the same regions and has been stored in the same vats4. This wine was packaged in two different formats: the traditional 0.75-L glass bottle and the 3-L bag-in-box. Several factors influenced the choice of this particular designation of origin. First, the Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC designation is one of the best-selling in supermarkets in Italy and is primarily used for domestic consumption [80, 81]. Moreover, we identified a producer for this wine who packages the same wine in the two formats considered in this study. This aspect is relevant as producers often pack different wines in different formats. In addition, for greater control over the research aimed at minimising the risk that the measure of the ‘format’ effect was contaminated by other factors such as the different quality of the wines analysed, a series of chemical and oenological characterisations were performed before the auction. The analyses, reported in Appendix A, demonstrate that the wines used in the auction, regardless of the format, have very similar oenological properties. Therefore, any differences perceived by consumers in the tastings were likely attributable to their perceptions and expectations regarding the two formats.

3.3. Experimental Procedure

In this study, we implemented an experimental auction to elicit consumers’ WTP for purchasing wine in the two formats considered. We utilised a second-price auction mechanism, which has been proven to be incentive-compatible [82], meaning that the respondent bidding their true value can maximise the probability of obtaining the highest benefit from the exchange. With this mechanism, the winner of the auction is the one who makes the highest bid, but the purchase price paid will be equal to the second-highest bid. Before and during the experiment, participants were not given any information regarding the market prices of the auctioned goods, as previous research has shown that providing reference prices influences the participants’ bids [83, 84].

In each auction session, participants were asked to compare, under various informative conditions described below, a wine packaged in a bag-in-box and in a bottle. To make the evaluation perfectly comparable, respondents were asked to express their WTP for four 0.75-L bottles, for a total quantity of 3 L, and for a 3-L bag-in-box.

The sessions were conducted in the sensory analysis laboratory of the marketing research company that recruited the participants in separate booths equipped with a tasting table and a computer. A total of eight auction sessions were organised, each with 12–13 participants, totalling 100 consumers, each of whom received at the end of the experiment a €10.00 shopping voucher for participating in the experiment.

The experiment was based on a within-subject design, and each session consisted of three rounds. In the first round (Blind tasting), two ISO glasses (30 mL per glass) were served, one containing Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC from a glass bottle and the other from a bag-in-box. The two wines were shown to participants with a different three-digit numerical code. All the experiment sessions were conducted in the same room under the same light conditions. The room has no windows and is lit by artificial lights. Participants were not given any information about the format, nor other information (e.g., brand, vintage, alcohol content, price) other than the denomination of origin of the wine. They were asked to taste the two wines and rate them on a seven-point hedonic scale ranging from 1 (Extremely Disliked) to 7 (Extremely Liked) [85]. Their hedonic ratings were based solely on the sensory aspects of the wines. The purpose of this round was to assess whether the format could have any effect perceivable by consumers on wine taste. No auction session was planned for the first round. In the second round (Only information), participants were asked to make a bid for four 0.75-L bottles of Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC wine and a bid for a 3-L bag-in-box of Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC. In this round, the participants were informed that the wines belonged to the same denomination of origin but were packaged in two different formats. To make sure that the burden and weight of the products did not influence the bids of participants who had come to the laboratory on foot or by public transport, it was specified that they could request home delivery for any products they won. After making their bids, the participants indicated their expectation of liking on the same hedonic scale used in the previous round. In the third and final round (Information and tasting) of the experiment, we observed the combined effect on consumer preferences of information about the format and the taste of the wine. This round aimed to demonstrate if wine taste could influence the expectation generated by the wine format and whether taste prevailed over the value associated with the format or conversely, taste had no impact on determining WTP. Specifically, two glasses of wine were served, one from a bottle and the other from a bag-in-box, each identified with a code different from that of the Blind tasting round. Participants were informed about which format corresponded to each code and were invited to make bids to purchase four 0.75-L bottles and a 3-L bag-in-box. After making their bids, participants again indicated their liking of the wines on a seven-point hedonic scale.

Having an organic product also allowed us to evaluate the potential effect of this production method on participants’ WTP. Therefore, maintaining the described procedure, in four of the eight sessions, it was communicated that the Montepulciano d’Abruzzo DOC wine was also organic. Thus, a total of 51 respondents participated in the auction knowing that the wines in question were organic.

In each round, no additional information (e.g., brand, price, year, alcohol content) was communicated to limit cognitive and anchoring bias [86–88].

At the end of the three rounds, the software randomly selected one of the two rounds to determine the auction winners and the wine prices. This procedure was necessary to prevent any participant from potentially winning all the auction rounds and thus purchasing an excessively large number of products, which could have influenced the value of bids in different rounds.

-

Step 1: Upon arrival, participants signed an informed consent form, which reminded them of their privacy rights related to the study, and that they were aware that if they won the auction, they would have to purchase the product. Each participant was randomly assigned an ID corresponding to the number of their tasting booth and experiment.

-

Step 2: Once all subjects were seated at their stations, a training period began. In this phase, enumerators reminded participants that it was forbidden to interact with each other by exchanging information or opinions, as well as to use their cell phones during the auction. Participants were also educated on the auction procedure and the second-price auction mechanism through a PowerPoint presentation, to ensure uniform training across all sessions. Additionally, it was highlighted that bidding zero was always an option if they were not interested in purchasing the product and that each of them could purchase at most two lots of red wine (those from the round randomly drawn at the end of the auction). At the end of the presentation, participants were allowed to ask the researchers questions about the procedure. The training period concluded with a trial round using a chocolate bar to familiarise participants with the auction mechanism [90]. After this auction session, participants were then allowed to ask for further information exclusively about the auction mechanism.

-

Step 3: After the training, the auction began, divided into the three consecutive aforementioned rounds: Blind tasting, Only information and Information and tasting. In each round, participants were not informed if they had made the highest bid, and no other information was provided regarding the bids of other participants, to prevent the bids made in subsequent rounds from being influenced by this information.

-

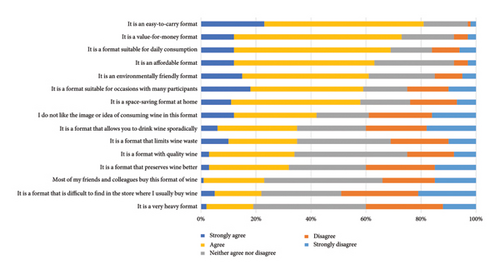

Step 4: At the end of the three rounds, participants completed an online questionnaire that included sociodemographic information, purchasing behaviours and wine knowledge. The questionnaires included two scales regarding wine involvement [91] and wine knowledge [70], where respondents were asked to express their agreement with a list of statements using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘Strongly Disagree’) to 5 (‘Strongly Agree’) (Table 2). Moreover, we investigated the determinants of bag-in-box wine purchasing by asking respondents to elicit their agreement to a list of 15 statements that described possible barriers and advantages of this wine packaging, by using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘Strongly Disagree’) to 5 (‘Strongly Agree’). The statements were the following: It is an affordable format; it is an easy-to-carry format; it is a value-for-money format; it is a format with quality wine; it is an environmentally friendly format; it is a format that preserves wine better; it is a space-saving format at home; it is a format that limits wine waste; it is a format that allows you to drink wine sporadically; it is a format suitable for daily consumption; it is a format suitable for occasions with many participants; it is a very heavy format; it is a format that is difficult to find in the store where I usually buy wine; I do not like the image or idea of consuming wine in this format; most of my friends and colleagues buy this format of wine.

-

Step 5: In the final phase of the experiment, a round was randomly selected to determine the auction winner and the trading price according to the second-price method for both the four 0.75-L bottles of wine and the bag-in-box. The winner(s) of the auction then purchased the products they won, paying a price equal to the highest bid made by the second-ranking person.

| Wine involvement |

| 1. I have a strong interest in wine |

| 2. Wine is important to me |

| 3. For me wine matters |

| 4. I choose my wine carefully |

| 5. Deciding which wine to buy would be an important decision to me |

| 6. Which wine I buy matters a lot to me |

| Wine knowledge |

| 1. I feel quite knowledgeable about wine |

| 2. Among my friends, I am one of the ‘experts’ on wine |

| 3. I rarely come across a wine that I have not heard of |

| 4. I know pretty much about wine |

| 5. I do not feel very knowledgeable about winea |

| 6. Compared to most other people, I know less about winea |

| 7. When it comes to wine, I really do not know a lota |

| 8. I have heard about most of the new wines that are around |

- aThese items were reverse-coded.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Therefore, the dependent variable is the difference between WTP for bottled wine () and WTP for bag-in-box wine (); xi is the vector of sociodemographic characteristics (gender and age), attitudinal factors (wine involvement, wine knowledge) inserted in the model as the mean of the related items and the variables related to the barriers and advantages of bag-in-box wine purchasing (descriptive statistics are given in Table A2, in Appendix B). Our analysis includes a nonlinear effect for age to account for the possibility that the relationship between age and preference for bag-in-box wines could not be strictly linear, with younger consumers preferring different types of packaging compared to middle-aged consumers [6, 33]. Finally, γ is the effect of round (Only information round was used as the base) and λ is the effect for those who receive the information that the wines are organic. Finally, ε is the error term.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 100 participants in the auction are shown in Table 3. Our sample replicates the statistics of the pilot study for gender and age, and it is represented predominantly by men over the age of 45 with secondary education. The average age of the sample is 52.7. Almost two-thirds of the participants were either employed or homemakers, while the remainder consisted of unemployed individuals, students and retirees. Most participants (52%) reported having a modest economic situation. The average mean of involvement is 3.86 (standard deviation 0.75), and the average wine knowledge is 3.35 (standard deviation 0.60).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–45 | 32 |

| 46–65 | 49 |

| > 66 | 19 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 64 |

| Female | 36 |

| Education | |

| Elementary school | 4 |

| Middle school | 27 |

| High school | 51 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 18 |

| Occupational status | |

| Employed | 52 |

| Student | 1 |

| Retired worker | 26 |

| Unemployed | 9 |

| Homemaker | 12 |

| Economic statusa | |

| Problematic | 4 |

| Modest | 48 |

| Reasonably good | 40 |

| Wealthy | 8 |

- aRespondents’ answers to the question ‘How does your income allow you to make ends meet?’.

Among the attributes considered in choosing wine, country of origin was deemed important by 83% of respondents, designation of origin by 79%, region of origin by 75% and packaging and occasion of consumption by 74%. The attribute with the least weight in wine purchasing was organic certification, considered slightly important or not at all important by 57% of respondents.

Regarding the determinants of bag-in-box wine purchasing (Figure 1), the majority of respondents (81% of the sample) agreed that the bag-in-box is an easy format to transport. About three-quarters of the sample (73%) agreed in recognising the bag-in-box as a format with a good value-for-money, while 69% considered it suitable for daily consumption and 63% an affordable format. While 61% of respondents considered it an environmentally friendly format, a quarter of the sample (24%) did not have an opinion regarding this attribute. Approximately half of the respondents (49%) did not find it difficult to find it in the store where they usually buy wine. Only a third of respondents agreed that it is a quality wine format (34%) and that it better preserves wine (32%). Finally, while 40% did not consider it a very heavy format, 41% had no opinion on this.

4.2. Auction

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics related to WTP in each round for each type of wine. In each round, the average bid for the bottled wine exceeded those for the bag-in-box. Therefore, participants are systematically willing to pay more for the bottled wine than for the bag-in-box wine. However, the variability was large across the two packaging and rounds, indicating a great preference heterogeneity for both packaging formats. The total of the zero WTP bids was scant. However, they were relatively more concentrated for the bag-in-box. This reinforces the idea that participants had a higher preference for bottled wine than for bag-in-box wine.

| Packaging | Only information round | Information and taste round | Both rounds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | No. of zeros | Mean | SD | No. of zeros | Mean | SD | |

| Bottled wine | 11.74 | 7.68 | 4 | 11.73 | 7.40 | 4 | 11.74 | 7.53 |

| Bag-in-box | 8.60 | 5.69 | 7 | 8.35 | 6.02 | 11 | 8.47 | 5.84 |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviations.

The results from the Blind tasting round showed that the rate of liking for bottled wine received an average score of 4.62 compared to 4.48 for bag-in-box wine with small standard deviations (1.28 for bottle and 1.27 for bag-in-box) for both, indicating a consensus of judgments among individuals. It is worth pointing out that a paired t-test (t = 0.89; p = 0.375) did not reject the hypothesis that the difference is zero. We concluded that participants perceived the wine from the two packaging as identical, how they are in reality. As a consequence, the higher preference for bottled wine over bag-in-box wine can be stemmed solely from packaging preference.

Table 5 reports the paired t-test between the WTPs and liking revealed across products and the rounds where WTPs were elicited. The results from the Only Information round showed that the average bid for bottled wine was 36% higher than the bids for bag-in-box. The difference was statistically significant at 99%. This seems due to the evidence that consumers expect bottled wine to be better than bag-in-box wine. This is confirmed by the evidence that the expected liking is higher and statistically significant.

| Mean (SD) | Paired Test | |

|---|---|---|

| Only Information round | ||

| Expected liking of bottled wine | 5.40 (1.04) | t = 9.66 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Expected liking of bag-in-box wine | 4.40 (1.15) | |

| WTP for bottled wine | 11.74 (7.68) | t = 6.61 p ≤ 0.001 |

| WTP for bag-in-box wine | 8.60 (5.69) | |

| Information and tasting round | ||

| Actual liking of bottled wine | 5.09 (1.31) | t = 4.83 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Actual liking of bag-in-box wine | 4.42 (1.33) | |

| WTP for bottled wine | 11.73 (7.40) | t = 7.71 p ≤ 0.001 |

| WTP for bag-in-box wine | 8.35 (6.02) |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviations.

This preference was further confirmed in the Information and tasting round where the consumers bid after tasting the wine from the two formats. In this case too, the average bid for bottled wine was higher and statistically more significant than the bid for bag-in-box wine. Although the respondents rated the same wine as the Blind tasting round, they elicited a greater and statistically more significant liking for the bottled wine. Therefore, packaging affected not only WTP but also the perceived wine liking.

It is worth noting that the bids of the Only Information round were the same as the Information and tasting round, indicating that the taste did not influence consumer preferences and that instead it is based on the packaging. Indeed, the liking of bag-in-box wine did not change between the two tasting rounds (4.48 in the Blind tasting round and 4.42 in the Information and tasting round), while the liking of the bottled wine increased in the last taste round (4.62 in the Blind tasting round and 5.09 in the Information and tasting round). It is interesting to observe how the anticipated liking for bottled wine is the highest (5.40), but it is adjusted downward once the blind tasting is conducted (4.62). In this case, consumers develop high expectations that positively influence the predicted appreciation. However, these expectations decrease when the real tasting experience is compared with the initial idea of the wine. At the same time, the tasting leads to an actual increase in the appreciation of bottled wine compared to blind tasting, reinforcing the belief that the bottle format has a positive influence on the overall perception of the product.

Finally, the results in Table 6 showed no significant difference in bidding behaviour between participants informed that the wines were organic and the bidding behaviour of those not informed. Indeed, the t-test between the grand means of the WTP for both packaging was not statistically significant. These results held even when we compared bids in each bidding round.

| Treatment | Packaging | |

|---|---|---|

Bottled wine Mean (SD) |

Bag-in-box wine Mean (SD) |

|

| Both rounds | ||

| Organic information | 12.35 (7.70) | 8.62 (5.95) |

| No information | 11.10 (6.86) | 8.33 (5.27) |

| t-test | t = 0.86 p = 0.394 | t = 0.26 p = 0.798 |

| Only information round | ||

| Organic information | 12.39 (8.21) | 8.84 (5.17) |

| No information | 11.08 (7.10) | 8.34 (6.18) |

| t-test | t = 0.85 p = 0.396 | t = 0.43 p = 0.665 |

| Information and tasting round | ||

| Organic information | 12.32 (7.78) | 8.39 (6.29) |

| No information | 11.13 (7.03) | 8.31 (5.80) |

| t-test | t = 0.80 p = 0.424 | t = 0.07 p = 0.946 |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviations.

4.3. Econometric Model

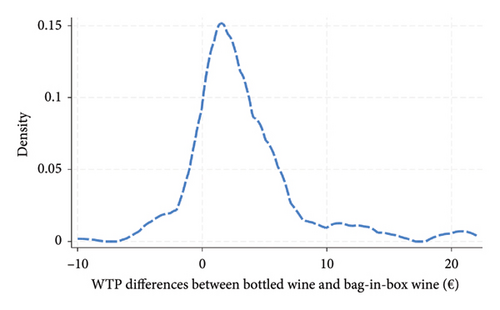

As mentioned above, we ran a regression using the difference in WTP between bottled and bag-in-box wine as the dependent variable. Figure 2, displaying the kernel density, shows that the participants generally exhibited a higher WTP for bottled wine compared to bag-in-box wine. Approximately 10% of consumers bid more for the bag-in-box, while three-quarters elicited a premium for bottled wine between zero and €10.00.

Table 7 shows the regression results. The treatment variable (‘Round’) was not statistically significant, confirming the t-test results. On average, consumer preferences remained unchanged even after tasting wines from both packaging formats. Similarly, the organic variable was not statistically significant, indicating that organic certification did not fill the WTP gap between bag-in-box and bottled wine. None of the coefficients related to gender, age and subjective knowledge were statistically significant. All coefficients related to barriers and advantages of bag-in-box wine but two were not statistically significant. The coefficient for ‘easy-to-find’ is positive and significant at 95%. The ‘peer-effect’ coefficient is significant at 95%, a negative sign. In other words, if an individual’s peers usually consume the bag-in-box wine, this reduces the consumer’s WTP gap between bottled and bag-in-box wine.

| Coef. | Std. Err. | p > t | Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.693 | 0.03 |

| Organic | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.313 | 0.07 |

| Gender | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.337 | 0.07 |

| Age | −0.31 | 0.21 | 0.147 | −0.91 |

| Age2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.156 | 0.88 |

| Involvement | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.218 | 0.11 |

| Knowledge | 1.02 | 0.67 | 0.128 | 0.13 |

| It is an affordable format | −0.42 | 0.51 | 0.412 | −0.08 |

| It is an easy-to-carry format | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.454 | 0.07 |

| It is a value-for-money format | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.185 | 0.14 |

| It is a format with quality wine | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.427 | 0.09 |

| It is an environmentally friendly format | −0.04 | 0.40 | 0.916 | −0.01 |

| It is a format that preserves wine better | −0.35 | 0.43 | 0.419 | −0.08 |

| It is a space-saving format at home | −0.30 | 0.40 | 0.451 | −0.07 |

| It is a format that limits wine waste | −0.42 | 0.40 | 0.299 | −0.10 |

| It is a format that allows you to drink wine sporadically | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.850 | 0.02 |

| It is a format suitable for daily consumption | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.676 | 0.04 |

| It is a format suitable for occasions with many participants | −0.08 | 0.31 | 0.805 | −0.02 |

| It is a very heavy format | −0.43 | 0.40 | 0.285 | −0.09 |

| It is a format that is difficult to find in the store where I usually buy wine | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.022 | 0.19 |

| I do not like the image or idea of consuming wine in this format | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.144 | 0.14 |

| Most of my friends and colleagues buy this format of wine | −0.90 | 0.45 | 0.048 | −0.20 |

| Constant | 3.13 | 6.08 | 0.608 | . |

- Note: Number of observations = 200; adjusted R2 = 0.16.

- Abbreviations: Coef. = coefficient and Std. Err. = standard error.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Preferences for bag-in-box wine were evaluated by determining the WTP through an experimental second-price auction. Measuring the impact of format on product quality perception using a methodology such as experimental auction, which involves the consumer in a real purchase situation in an incentive-compatible context, offers solid and useful results for producers and retailers who are considering differentiating packaging, as well as for better defining their marketing strategies [15].

Starting with identical wines packaged in two different formats, consumers correctly perceived the two wines as identical based solely on taste, assigning them equal liking. This result seems to suggest that technological advances in recent decades have improved the quality of bag-in-box manufacturing, making this type of format suitable for maintaining the organoleptic properties of wine intended for everyday use, rather than ageing [4].

However, when consumers expressed their purchase preferences, they showed a lower WTP for bag-in-box compared to the traditional glass bottle. Specifically, the WTP for the traditional glass bottle exceeded that of bag-in-box wine of the same designation of origin by approximately 37%. This difference in value seems primarily due to the expected liking of the glass bottle being greater.

The differences in WTP were confirmed by consumers even after expressing their preferences following informed tasting, i.e., knowing the formats of the wines tasted. The most interesting aspect concerns the taste rating. In fact, it was expected that these would not be statistically different from those expressed in the Blind Tasting round. Consumers rated the bottled wine higher than the bag-in-box wine, merely because it was bottled. However, the anticipated expectation (without tasting) for bottled wine decreases when people compare their initial idea with the actual tasting experience. At the same time, tasting leads to a real increase in the appreciation of bottled wine compared to blind tasting. This suggests that the bottle format, on the one hand, raises initial expectations and, on the other hand, enhances perception compared to blind tasting.

Therefore, a different role and impact of format on liking can be observed: in the case of wine in BIB, this does not influence either anticipated appreciation or actual appreciation. In contrast, the bottle increases both initial expectations and actual appreciation, leading to an increase in liking compared to blind tasting.

This study confirms the importance of packaging in wine choice [24, 25], as it emerges that the format impacts the WTP for red wine intended for daily consumption. Moreover, the results seem to confirm that Italian consumers prefer glass bottle to packaging alternatives [14, 31]. This result could be explained by a halo effect exerted by the format, in line with the conclusions of Apaolaza et al. [92] and Demartini et al. [93]. In other words, for consumers, the format is a value in itself, and therefore, they are not willing to change their WTP even realising that the format does not impact taste. This result suggests the ineffectiveness of developing promotions for bag-in-box wine through tastings.

This bias against the bag-in-box is confirmed by regression results, where the preference for bottled wine appears at least in part to be socially determined. Interestingly, those who believe they project a bad image of themselves to others by drinking the bag-in-box show a higher premium for bottled wine. In contrast, consumers who know that their peers already drink bag-in-box wine have on average a lower premium for bottled wine. This might explain why consumers, who perceived the two wines as identical in the blind tasting, are willing to pay more for bottled wine once they know the wine packaging. Unsurprisingly, individuals who generally face some difficulty in sourcing bag-in-box develop a greater preference for bottled wine. Regarding how sociodemographic and attitudinal characteristics influence WTP for wine in different formats, our study showed that gender and age do not affect the consumer preference for wine packaging, such as wine knowledge. These results seem not to confirm the findings of Capitello et al. [33] concerning sociodemographic characteristics.

Considering the peer influence of the bag-in-box, producers and marketers have the opportunity to develop marketing strategies for promoting this format based on the use of elements that make bag-in-box consumption cool. For example, showcasing the ‘cool’ aspects of bag-in-box wine consumption in supermarkets or on social media platforms can be a powerful marketing tool. Influencer partnerships, user-generated content and engaging campaigns can further enhance the product’s social appeal. At the same time, also enhancing the environmental benefits of bag-in-box over glass bottles can impact the consumers’ decision-making process for wine.

Another aspect analysed concerns the possible effect of organic certification in determining WTP for the different formats. The results show that organic certification does not change the WTP for bottled and bag-in-box wines for DOC wine for everyday consumption in a statistically significant manner. The analysis of the questionnaire responses given by participants after the auction highlighted how organic certification is considered the least important attribute in choosing a wine for daily consumption. These results are in line with previous studies that pointed out how organic wine is not preferred by the average consumer [17, 21]. The responses in terms of WTP are thus consistent with the purchasing behaviour of the involved consumers.

The results were obtained by isolating the effect of the format alone compared to all other attributes that consumers normally consider important in the perception of quality and in the formation of a wine’s value, such as brand, origin, label design and price. Nonetheless, although the identified WTP does not represent the total surplus linked to that product, measuring the economic impact of the format on WTP provides important strategic information for bag-in-box wine producers. Moreover, it should be kept in mind that the experiment was conducted with wines included in a specific price group, which may affect the generalisability of the findings. The WTP differences identified in this study may be heterogeneous across wines present in different price categories.

This study has limitations that can be addressed in future research. The results highlight some determinants of the WTP’s difference between the two formats. However, there could be other dimensions to explore. For example, the health impacts of the two formats could be perceived differently. A bag-in-box (a 3-L format) could reflect a negative image of health compared with a smaller container. Another limitation of the current study is that it analysed a specific type of red wine, a limitation that could be overcome through future research developments to test the impact of format on WTP starting from different types of wine and designations of origin. Despite attempting to recreate a real purchase scenario in this experiment, the information provided to participants was partial compared to what consumers can find on the market. First and foremost, no information was given about the brand or other attributes that impact wine purchase choices, such as grape variety or vintage. Future studies could include this information, considering the possible interactions between packaging and various choice attributes. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted purchasing habits, leading to flare-up sales of bag-in-box in Italy [10]. Although we conducted the experiment at the end of 2022, when the state of emergency in Italy had already been lifted and people had returned to ordinary life, the results of the study may still have been influenced by the consequences of these changing purchasing behaviours.

6. Managing and Policy Implications

Strategies aimed at improving the environmental and economic sustainability of the wine industry must also address packaging. In this context, the previous literature demonstrates how bag-in-box, with equivalent product volume, is the least environmentally impactful format [7, 8]. Therefore, directing the wine industry towards better environmental performance also means increasing the share of wine in bag-in-box format as a suitable substitute for bottled wine for daily consumption. However, this transition is hindered by consumers’ perception of these types of packaging. While technological advancements have eliminated taste differences between wines packaged in glass bottles and bag-in-box, consumer preference for the latter remains significantly lower when compared to the traditional glass bottle. Addressing consumer preferences, altering social perception and overcoming the stigma associated with this format seem necessary steps for increasing wine consumption in bag-in-box. However, communication aimed at enhancing the image and desirability of this format can only promote more environmentally sustainable wine consumption when integrated with a broader consumer environmental education strategy. Our research highlights that the environmental dimension of sustainability is not a crucial factor in purchasing wine for daily consumption.

Policy implications regarding strategies to increase wine consumption in bag-in-box compared to the traditional glass bottle are thus complex and require a holistic approach that considers not only economic factors related to WTP but also social ones. The halo effect associated with bag-in-box can be overcome through communication targeted at younger consumers, who exhibit a more open and favourable attitude towards packaging alternatives to the glass bottle [5]. Communicative strategies should consider key aspects such as educating and raising consumer awareness about the environmental and economic benefits of wine in bag-in-box compared to bottles. Campaigns could, for instance, illustrate the environmental benefits of reducing glass waste and lower transportation costs associated with bag-in-box.

Policies should also incentivise collaboration among wine producers, distributors and retailers to promote wine in bag-in-box. This collaboration could involve joint efforts to enhance the perception and appeal of bag-in-box through marketing and advertising. In this context, research and development of new sustainable packaging technologies could further improve the market acceptance of bag-in-box. Policies should support innovation in the packaging sector, with a particular emphasis on reducing environmental impact.

Our work, in addition to highlighting a negative effect (halo effect) of bag-in-box compared to bottled wine that directly impacts consumer WTP, nonetheless suggests economic development potential for this packaging type as the average difference between the estimated WTP for bag-in-box and glass bottle is much smaller than the average market prices observed for denomination red wines in large-scale retail. This implies that the current market prices underestimate the actual utility of the product in a bag-in-box. In this context, the existence of a consumer segment for whom an upward alignment of bag-in-box prices compared to glass bottle prices would allow an increase in profit margins on this type of product.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the UNICESV-University Research Center for the Competitive Development of the Wine Sector. https://www.unicesv.unifi.it/.

Acknowledgement

The publication was made with the contribution of the researcher Andrea Dominici with a research contract cofunded by the European Union-PON Research and Innovation 2014-2020 in accordance with Article 24, paragraph 3a, of Law No. 240 of December 30, 2010, as amended, and Ministerial Decree No. 1062 of August 10, 2021.

Endnotes

1The Italian wine classification system legally recognises, within the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) certification, Controlled Designation of Origin (DOC) and Controlled and Guaranteed Designation of Origin (DOCG) wines. Both DOC and DOCG designations indicate quality wines produced in specific delimited areas following a precise set of rules. However, DOCG wines are subject to stricter requirements and must follow more stringent production rules compared to DOC wines. For a detailed explanation of Italian PDO institutional for wine setting, see the work of Resce and Vaquero-Piñeiro [100].

2Information on the characteristics of Italian wine consumers was obtained by analysing data from the 2020 ‘Aspetti della vita quotidiana’ survey conducted by ISTAT.

3At the time of purchase, the market price of a single bottle was €4.50, while the BIB was sold for €13.00.

4The wine used for the auction was produced in 2021, making it the most recent available on the market at the time of the auction (November 2022). While the glass bottle has no expiration date, the producer specified on the BIB label that it is preferable to consume the product by May 2023.

Appendix A: Materials and Methods

Wines were chemically characterised according the following methods previously reported in the work of Maioli et al. [94].

Chemical Standard Parameters. The standard parameters (pH, titratable acidity, volatile acidity, alcohol content, residual sugars, malic acid, lactic acid, citric acid and tartaric acid) were measured through FT-IR spectroscopy analyses using FOSS WineScan (FT 120 Reference Manual, Foss, Hamburg, Germany). Wine samples were centrifuged before analysis (10,000 rpm × 10 min). The dosage of free and total SO2 was obtained using a kit of reagents for SmartAnalysis instrument (DNAPhone srl, Parma, Italy). All of the analyses were performed in triplicate.

Phenolic Profile by RP-HPLC-DAD. Monomeric anthocyanins, tannins and polymeric pigments (coloured polymeric pigments resistant to sulphite bleaching) were quantitated by HPLC [95], and the analysis was carried out on a PerkinElmer Series 200 LC equipped with an autosampler and a diode-array detector (DAD series 200) (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA). Chromatograms were acquired at 520 nm, recorded and processed using Total Chrome Navigator software (PerkinElmer). Acetonitrile of HPLC grade was from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Orthophosphoric acid and ethanol of analytical reagent grade were from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). The identity of monomeric anthocyanins and polymeric pigments by HPLC-DAD was achieved by comparing the retention times and UV spectra with reference standards previously injected. In order to convert the peak area into mg/L, a calibration curve was performed with four solutions of malvidin-3-O-glucoside at four different concentrations (25, 50, 100 and 200 mg/L), acquiring chromatograms at 520 nm. All solutions were prepared using an acidic hydroalcoholic medium (12% v/v ethanol, 5 g/L tartaric acid, pH 3.5). Malvidin-3-O-glucoside ≥ 99% was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA). Wine samples were centrifuged before analysis (10,000 rpm × 10 min). All of the analyses were performed in triplicate.

Colour Indices. Colour intensity (CI) and hue (Hue) were measured according to the method of Glories [96] and the total phenols index (TPI) as described by Ribereau-Gayon [97]. CI was measured using a 1-mm path length quartz cell and expressed as the sum of absorbances at 420 (A420), 520 (A520) and 620 nm (A620) and referred to a 10-mm path length (× 10). Wine hue was measured using a 1-mm path length quartz cell and expressed as the ratio between absorbance at 420 (A420) and 520 nm (A520). TPI was measured as absorbance at 280 nm using a 10-mm path length quartz cell, and samples were diluted 1:100 with an Elix 5 System (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) absorbance of the samples was measured on SmartAnalysis (DNAPhone srl, Parma, Italy). Elix 5 System water was used as a reference. Wine samples were centrifuged before analysis (10,000 rpm × 10 min). All of the analyses were performed in triplicate.

CIELab Coordinates. CIE (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage) L∗, a∗, and b∗ colour coordinates were measured according to OIV [98]. Visible spectra were recorded at 380–780 nm using a 1-mm path length quartz cell and SmartAnalysis (DNAPhone srl, Parma, Italy). Elix 5 System water was used as a reference. Colour differences between wines were determined during ageing using the ΔE value of the CIELab diagram. When ΔE > 3, the differences between wines are perceivable by human sight [99]. Wine samples were centrifuged before analysis (10,000 rpm × 10 min). All of the analyses were performed in triplicate.

Data Analysis. Microsoft Excel was used for data collection and processing. All the chemical data were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (chemical analyses performed in triplicate) and analysed by multifactor analyses of variance (MANOVA) applying an LSD, least significant difference test, with 95% significance level, using Statgraphics Centurion (Ver.XV, StatPoint Technologies, Warrenton, VA). Packaging materials (glass bottle and bag-in-box) and analysis replicates were considered as factors.

Results and Discussions

Chemical characterisation of wine

Phenolic composition and colour indices were determined in order to discriminate wines bottled in different materials such as 0.75-L glass bottle and 3-L bag-in-box (Table A1).

| Glass bottle wine (0.75 L) | Bag-in-box wine (3 L) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content (% v/v) | 13.56a ± 0.01 | 13.61b ± 0.01 | 0.0234 |

| Residual sugar (g/L) | 15.88b ± 0.03 | 13.71a ± 0.02 | 0.0001 |

| Titratable acidity (g/L) | 5.61a ± 0.02 | 5.81b ± 0.02 | 0.0067 |

| Volatile acidity (g/L) | 0.37b ± 0.01 | 0.35a ± 0.01 | 0.0153 |

| pH | 3.52a ± 0.01 | 3.51a ± 0.02 | 0.6667 |

| Malic acid (g/L) | 0.52a ± 0.01 | 0.62b ± 0.01 | 0.0039 |

| Lactic acid (g/L) | 0.70a ± 0.01 | 0.69a ± 0.01 | 0.6784 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 2.84b ± 0.01 | 2.81a ± 0.01 | 0.0153 |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.25a ± 0.01 | 0.25a ± 0.01 | 0.6675 |

| Free SO2 (mg/L) | 15a ± 1 | 16a ± 1 | 0.6667 |

| Total SO2 (mg/L) | 27b ± 1 | 24a ± 1 | 0.0153 |

| Total phenols index | 80.26b ± 0.02 | 79.68a ± 0.01 | 0.0002 |

| Colour intensity | 19.87b ± 0.03 | 19.36a ± 0.08 | 0.0036 |

| Hue | 0.59a ± 0.01 | 0.61b ± 0.01 | 0.0377 |

| L∗ | 4.37a ± 0.06 | 4.90b ± 0.01 | 0.0039 |

| a∗ | 28.96a ± 0.10 | 31.10b ± 0.02 | 0.0006 |

| b∗ | 7.51a ± 0.04 | 8.42b ± 0.01 | 0.0005 |

| DE | 2.39 | ||

| Total monomer anthocyanins (mg/L malvidin-3-O-glucoside) | 76.25a ± 0.82 | 83.30b ± 0.70 | 0.0005 |

| Polymeric pigments (mg/L malvidin-3-O-glucoside) | 134.49b ± 0.37 | 124.68a ± 0.39 | 0.0016 |

| Tannins (mg/L (+)-catechin) | 1660.78a ± 13.60 | 1705.13b ± 6.61 | 0.0111 |

- Note: On each row, different letters indicate significant differences among values at p ≤ 0.05.

All the variables were significantly different according to ANOVA except for pH, lactic acid, citric acid and free SO2. Despite these, DE was 2.39, indicating that the differences between wines were not perceivable by human sight [99].

Appendix B: Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Median | Interquartile range | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is an affordable format | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is an easy-to-carry format | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a value-for-money format | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format with quality wine | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 5 |

| It is an environmentally friendly format | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format that preserves wine better | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a space-saving format at home | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format that limits wine waste | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format that allows you to drink wine sporadically | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format suitable for daily consumption | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format suitable for occasions with many participants | 4 | 1.5 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a very heavy format | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| It is a format that is difficult to find in the store where I usually buy wine | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| I do not like the image or idea of consuming wine in this format | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Most of my friends and colleagues buy this format of wine | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.