Determinants of Male Partner Participation in Antenatal Care at Kangundo Hospital, Kenya

Abstract

Male partner involvement (male partner participation (MPP)) in antenatal care (ANC) is shown to boost ANC attendance and compliance to recommendations, which in turn improves maternal and newborn health outcomes. MPP is still low in Kenya and in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) despite this. According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (2014), the MPP rate was 30%. Burundi (18.2%), Senegal (31.8%), and Zimbabwe (32.4%) showed comparable patterns. The purpose of this study was to identify the key factors affecting MPP in ANC visits as well as its prevalence. An analytical cross-sectional study design was conducted on a sample size of 250 mothers seeking childcare services in Kangundo, Machakos County, and Kenya, from July and August 2023. Participants were selected using systematic random sampling and data was collected using a structured questionnaire. Descriptive analysis was performed on all variables and associations with MPP were examined using the Chi-square (χ2) test. Logistic regression was used and a step-wise Akaike information criterion was done to determine the predictors of MPP. The prevalence of MPP in Kangundo was 29%. The significant predictors of MPP were health education (OR = 34.12; 95% CI: 13.36–95.55; p-value = 0), pregnancy complication (OR = 17.99; 95% CI: 5.62–66.72; p-value = 0), and the pregnant mothers request for male partner accompaniment to ANC (OR = 7.39, 95% CI: 3.04–19.77). In conclusion, to promote MPP, the study recommends that targeted healthcare education should be prioritized to inform male partners of their role and the importance of participating in ANC. The healthcare system must create an inclusive environment that facilitates MPP rather than relying solely on mothers to encourage their partners.

1. Introduction

Enhancing the provision of maternal healthcare is salient in managing and preventing maternal morbidity and mortality, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) which accounts for over 57% of global maternal deaths [1–3]. Ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages (SDG3), and its precursor, improving maternal health (MDG 5), aimed at reducing maternal morbidity and mortality globally. An important component in improving maternal healthcare provision is antenatal care (ANC), an all-inclusive term incorporating health education, screening, preventative, and diagnostic services to women during pregnancy to mitigate maternal and child complications [4]. A critical but often underutilized component in enhancing the universality of ANC is male partner participation (MPP), especially in low- and middle-income countries where gender inequities are key to decision-making [5, 6]. MPP in maternal health denotes the active involvement of male partners in various aspects of maternal care, from ANC to delivery and postpartum support, and has been characterized as a social and behavioral transformation process encouraging men to assume greater accountability in maternal healthcare [7]. It has been shown that MPP enhances utilization of skilled and institutional delivery for mothers, uptake of pre- and postpartum hospital visits, and increased utilization of contraception, all integral elements in maternal health and wellbeing [8, 9]. In addition, MPP has been shown to support better nutrition for mothers, higher rates of breastfeeding, and better development of young children underscoring the need to encourage and incorporate male partners in ANC as a part of the broader strategies to mitigate preventable maternal morbidity and mortality [10–14].

Challenges and barriers to male engagement in maternal health like lack of access to inclusive and integrated quality services have been documented, especially in the SSA region [15–18]. MPP in ANC prevalence rates vary widely in SSA ranging from 18% in Burundi to 32%, 44%, and 87% in Senegal, Mozambique, and Rwanda, respectively [11]. Thus, despite some successes, significant barriers continue to exist. Male engagement in SSA’s maternal and child health services is influenced by sociodemographic factors encompassing the partner’s age, marital status, educational attainment, and occupation [19, 20]. In addition, social factors, including cultural beliefs and religion, attitudes and stereotypes, and communication [21, 22], and health services-related determinants such as poor health facility staff attitudes, harsh/critical language from attending staff, and restrictions on male access to delivery or ANC rooms have been shown to reduce male engagement [19, 21]. On the other hand, health education through community health workers or public media, timing of ANC visits, positive attitude/beliefs towards maternal health, privacy, and emphasis on male involvement have been shown to enhance both initiation and male participation in ANC [23], highlighting possible strategies for increasing male engagement in maternal health services.

In Kenya, like many SSA countries, MPP in ANC attendance is low due to a myriad of factors [24–30]. A national survey on MPP in family planning and reproductive health estimated MPP in ANC visits at approximately 30% [31], a reflection of significant barriers. Broadly, strategies for improving maternal healthcare uptake in Kenya have centered on equity and resources, managing community health provision, especially in the rural areas, enhancing key prenatal care interventions, and health education [32, 33]. However, there are underlying individual and community-level factors that hinder its uptake, especially MPP. For instance, research conducted at Kangundo level 4 hospital has shown low MPP rates attributable to distance from the health facility, occupational engagement by men, and perceived gender roles in the ANC [35]. In a different study, MPP in ANC was associated with increased adoption of measures aimed at preventing vertical and sexual HIV-1 infections such as condom use, refraining from breastfeeding, and use of antiretroviral therapy, outcomes attributable to attending counseling together, living together, and health education [36].

There is still a significant knowledge vacuum on the local contextual elements that affect MPP in ANC within the Kangundo sub-county, despite the fact that these studies emphasize the significance of MPP and some of the obstacles to its adoption.The interaction of sociodemographic, obstetric, and health system factors that influence MPP in this particular context has not been thoroughly examined in previous studies. To enhance MPP and, consequently, mother and child health outcomes, it is imperative to close this gap and create tailored and context-specific interventions. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to look into the sociodemographic, obstetric, health system, and prevalence aspects related to MPP in ANC in Kenya’s Kangundo sub-county. By doing this, it hopes to offer evidence-based insights that can guide focused tactics to improve MPP and support the larger objective of enhancing maternal healthcare services in Kenya.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at a level 4 hospital in Kangundo sub-county, Machakos county, Kenya. Administratively, it is situated in Machakos County’s Isinga sublocation and Kangundo location. The facility is close to government buildings, businesses, residences, and small-scale subsistence farmers. The latitude of Kangundo is −1.305567 and the longitude is 37.345321. Kangundo is a city located in Kenya with the GPS coordinates of 1°18′20.0412′’ S and 37°20′43.1556′’ E. The elevation of Kangundo is 1640.322 the hospital occupies a land area of 5 acres on average. The ANC clinic and MCH are operational from Monday to Friday from 8 am to 5 pm. Kangundo sub-county has a population of 97,917,172.7 km2 area, 567.0 km−2 population density [37]. Kangundo level 4 hospital is a rural facility with a history of low male and female engagement across many maternal and child care levels [35, 38, 39], despite some successes in child immunization [40]. In addition, there is a widespread utilization of traditional birth attendants with pregnancy-associated complications being common [41].

2.2. Study Design

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in Kangundo Hospital in eastern Kenya, between August and September 2023.

2.3. Study Variables

2.3.1. Dependent Variable

- •

Yes

- •

No

MPP was assessed by collecting data if the man did accompany her spouse to the clinic for the ANC visit physically while she was pregnant.

2.3.2. Independent Variables

- i.

Sociodemographic factors

- ii.

Obstetric factors

- iii.

Health system factors.

2.4. Target Population

The target population was mothers seeking childcare services at Kangundo level 4 hospital who had delivered in the last year. A child health services clinic was used because mothers seek immunization services for children who are mainly under 1 year old. According to the Kenya demographic survey, children aged between 2 and 23 months and fully vaccinated in Machakos county are at 88%, therefore, the clinic provides a good representation of mothers who delivered in the last year [40].

2.5. Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion

The criteria for inclusion were mothers who attended ANC clinic in any facility in the Kangundo sub-county during their pregnancy, mothers who were seeking childcare services at Kangundo hospital, and finally mothers who had given birth in the last year. In order to guarantee the freshness of the data, mothers who had previously taken part in a comparable study within the last 2 years were excluded, as were mothers who were not Kangundo residents and were merely visiting to make sure the study represented the local population context.

2.6. Sample Size

The sample size was based on 18% MPP in the Bumnyala sub-county [42]. Assuming a similar MPP proportion in the Kangundo sub-county, we estimated the required sample size for this study at a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 227 using the open, version3 [43]. Parameters that were utilized by the openEpi calculator to calculate the sample size include a CI of 95%, the estimated proportion of the 18% in the Bumnyala sub-county, the expected proportion for Kangundo assuming a similar male partner rate in Kangundo, the population size of Kangundo, and a CI width. We further adjusted the figure by 10% for inconsistencies and incompleteness arriving at a total sample size of 250 participants. The 10% was incorporated to cater to unforeseen challenges that might occur in the process of data collection such as participant’s nonresponse and also to enhance the robustness of the study results [44].

2.7. Sampling Procedure

Using a systematic random sampling technique, every fifth mother seeking services was picked to participate [45] until the required number of 250 was attained. The first participant was randomly selected using the simple random sampling technique. The number of mothers who visited Kangundo level 4 hospital seeking childcare services in Kangundo in the past 1 year ranged between 40 and 60 per day. An average number was determined to be 50 and then divided 250 the target population with 50, hence, arriving at the fifth person that was selected in the study.

2.8. Piloting

Piloting of the study tools was done in Athiriver level 4 hospital and the participants were people in the inclusion area. Pretesting the questionnaires was done by the principal investigator and the research colleagues to assist in determining whether the sampling techniques and data collection instruments were adequate. The sample population of the piloting study was 25 participants, which was 10% of the sample size for the whole research.

2.9. Data Collection

Data was collected using a structured questionnaire using the Kobo toolbox following consent from the respondents and pretesting by the lead investigator. The main outcome was a binary variable MPP (Yes/No). The questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare system factors, and obstetric factors every participant was made aware of the purpose and objectives of the study, rights, confidentiality, and process involved. Verbal and written consent was voluntarily sought from each respondent before participation in the study. Ethical clearance was acquired from Mount Kenya University (195 REF MKU/ISERC/2908), while permission to conduct research was granted from the National Council of Science and Technology (NACOSTI/P/23/27865). Local authorities including hospital administration also provided permission for the study.

2.10. Validity and Reliability of the Measurement Tools

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to assess for validity. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.75 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant p < 0.001, indicating that the data was suitable for factor analysis. Principal component analysis with varimax rotation identified three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 65% of the total variance. The factor loadings confirmed that the items were appropriately grouped, supporting the construct validity of the questionnaire.

Internal consistency of the variables was evaluated using the Cronbach alpha test of reliability results obtained from the model showed that the variables were related with a Cronbach value of 0.7 implying good internal consistency between all the variables in the questionnaire and that the variables were reliable to draw meaningful conclusions. When the dependability coefficient was at least 0.6, it was acceptable for all the constructs and was regarded as suitable for the investigation. The acceptable reliability coefficient is 0.6 and above [46].

2.11. Data Processing and Analysis

Questionnaire data were downloaded from the Kobo toolbox and exported to R (http://CRAN.R-project.org/) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to create summaries of male participation across levels of different factors. Categorical variables were explored through tabulation and frequencies. Assessment of associations was done using a logistic regression for variable selection to reduce dimensionality. Multicollinearity was assessed through variable inflation factors (VIFs) with the correlation cut-off set at VIF < 10 [47]. Measures of effect were reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

2.12. Study Limitation

The study was conducted in Kangundo, Kenya, and may not be generalized to other populations. The nature of the study relied mostly on recalling the nature of the mothers during the ANC session, as certain mothers may not be confident in their responses, though clearly stating the questions and explaining them to the mothers in a form that they understand what the question entails was used to minimize the limitation.

3. Results

3.1. MPP Survey

The proportion of pregnant women attending ANC who were accompanied by their partners was 29% (Table 1). Out of those mothers, 72 (29%) were accompanied by their spouses at ANC and 59/72 (82%) of them attended more than four ANC visits.

| Male partner participation | Count | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No | 178 | 71.2 |

| Yes | 72 | 28.8 |

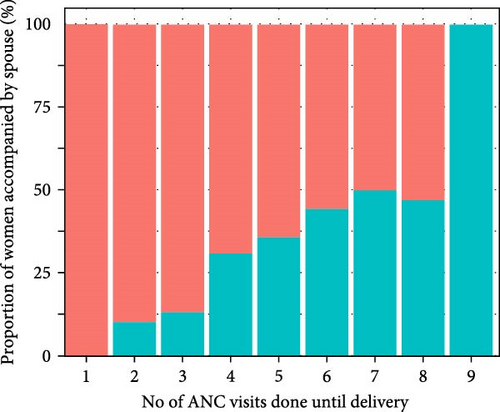

Figure 1 shows the proportion of women who were accompanied by their male partner and the number of ANC visits they had till delivery. The women who did go for nine ANC visits had 100% accompaniment by the male partner, while women who did go for only one ANC visit had no MPP.

Table 2 shows the age group 20–29 years old had the highest proportion 39/72 (55%) of male partner accompaniment during their ANC visits followed by the age group 30–39 with 20/72 (28%) and last was the age group 40+ with 25%(χ2: 19.34, p = 0.001). The number of children significantly influenced MPP, where those who were pregnant with their first child had a higher proportion accompaniment of 61% compared to those who were pregnant with their second child or more at 18/72 (24%; χ2: 32.04, p = 0.001). The majority of the men with a university education 49/72 (68%) did participate in ANC while those with lower education participated only 20/72 (28%; χ2: 13.59, p = 0.001). MPP with women who had a pregnancy complication like (pre-eclampsia) was at 50/72 (70%; χ2: 30.97.45, p = 0.001).

| Variable | Male Partner Participation (n (%)) | p-Value | Chi-square value (χ2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Spouse (years) | Yes | No | — | — |

| 20–29 | 52 (55%) | 43 (45%) | <0.001 | 19.34 |

| 30–39 | 28 (28%) | 71 (71%) | ||

| 40+ | 14 (25%) | 42 (75%) | ||

| Occupation of the spouse | ||||

| Casual worker | 29 (36%) | 51 (63%) | 0.423 | 1.72 |

| Employed | 26 (45%) | 32 (55%) | ||

| Self Employed/Business | 39 (35%) | 73 (65%) | ||

| No. of children | ||||

| 1 child | 56 (61%) | 36 (39%) | <0.001 | 32.04 |

| 2+ children | 38 (24%) | 120 (76%) | ||

| Setting | ||||

| Rural setting | 63 (33%) | 127 (67%) | 0.015 | 5.89 |

| Urban setting | 31 (52%) | 29 (48%) | ||

| Education of the spouse | ||||

| Lower education | 26 (28%) | 67 (72%) | <0.001 | 13.59 |

| College | 51 (39%) | 81 (61%) | ||

| University | 17 (68%) | 8 (32%) | ||

| Multiple births | ||||

| Yes | 7 (64%) | 4 (36%) | 0.132 | 2.26 |

| No | 87 (36%) | 152 (64%) | ||

| Miscarriage/still birth | ||||

| Yes | 16 (70%) | 7 (30%) | 0.002 | 9.58 |

| No | 78 (34%) | 149 (66%) | ||

| Pregnancy complication | ||||

| Yes | 29 (81%) | 7 (19%) | <0.001 | 30.97 |

| No | 65 (30%) | 149 (70%) | ||

| Discussed with spouse on him accompanying her to ANC | ||||

| Yes | 77 (52%) | 72 (48%) | <0.001 | 29.69 |

| No | 17 (17%) | 84 (83%) | — | — |

In Table 3, from the 69 pregnant mothers who did receive health education during the routine ANC on the importance of MPP 80% of their male partners did participate in ANC (χ2: 69.57, p-value = 0.001). Mothers whose spouses did receive health provisions and services like HIV testing and family planning counseling while accompanying them in ANC did have a participation of 37%, while those who did not receive any service or provision had a participation of 39% (χ2: 0.03, p = 0.858). Women who came to the facility and were encouraged to come with their partners for ANC during the routine ANC were 7%. Of the women who were encouraged to come with partners by the health care workers 50% of them did come with their partners, while the pregnant women who were not encouraged to come with partners by the health care workers did come with their partners it was at 28% (χ2: 3.21, p = 0.05). Most of the mothers had a positive attitude towards being accompanied by their male spouses during ANC visits. Women who did agree that their spouses should accompany them to ANC even after providing the finances was 26% and out of those only 20% were accompanied by their spouses to ANC and out of the ones who were accompanied by their spouses to ANC 32% of those who did agree that men should accompany them (χ2: 2.76, p = 0.05). Women who disagreed that the hospital provided a good environment for their spouses were 91.6% and among those who were accompanied by their spouses to the ANC clinic were 30% (χ2: 0.61, p = 0.05). Women who did agree that every pregnant woman should plan on where to go to ANC were 82% and among those the ones who were accompanied by their spouses were 24% (χ2: 13.66, p = 0.001). The proportion of women who did agree that the man should decide whether the woman should go for ANC was 55% and among those the ones who were accompanied by their spouses to the facility were 25% (χ2: 2.17 p = 0.05). Thirty-eight percent did agree that their spouses should accompany them to the facility and out of those who did agree 17% were accompanied by their spouses to the facility (χ2: 9.29, p = 0.05).

| Variable | Male Partner Participation (n (%)) | p-Value | Chi-square value (χ2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Health care worker (HCW) encouraged male participation | ||||

| Yes | 11 (61%) | 7 (39%) | 0.059 | 3.55 |

| No | 83 (36%) | 149 (64%) | ||

| HCW did offer health education on MPP | ||||

| Yes | 55 (80%) | 14 (20%) | <0.001 | 69.57 |

| No | 39 (22%) | 142 (78%) | ||

| HCW did offer men who attended ANC services and provisions | ||||

| Yes | 59 (37%) | 101 (63%) | 0.858 | 0.03 |

| No | 35 (39%) | 55 (61%) | ||

| Was the queue at the hosipital long | ||||

| Yes | 8 (57%) | 6 (43%) | 0.204 | 1.61 |

| No | 86 (36%) | 150 (64%) | ||

| Women’s perspective on male partner participation | ||||

| No need for the man to accompany wife to ANC so long as he provides finances | ||||

| Agree | 71 (38%) | 114 (62%) | 0.779 | 0.078 |

| Disagree | 23 (35%) | 42 (65%) | ||

| The hospital provided good environment for men who accompained their wife | ||||

| Agree | 6 (29%) | 15 (71%) | 0.511 | 0.4318 |

| Disagree | 88 (38%) | 141 (62%) | ||

| A woman should plan ahead of time where to go for ANC | ||||

| Agree | 69 (34%) | 135 (66%) | 0.15 | 5.89 |

| Disagree | 25 (54%) | 21 (46%) | ||

| The man should decide whether if the spouse can go for ANC or not | ||||

| Agree | 48 (35%) | 90 (65%) | 0.3737 | 0.79 |

| Disagree | 46 (41%) | 66 (59%) | ||

| A woman partner should accompany her to the facility for ANC visits | ||||

| Agree | 31 (33%) | 63 (67%) | 0.301 | 1.073 |

| Disagree | 63 (40%) | 93 (60%) | ||

3.2. Association Between MPP and Other Variables

Logistics regression analysis results are presented in Table 4. Mothers who did agree that their male partners should accompany them for ANC after providing the finances had (OR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.19–1.28; p = 0.15). Spouses whose partners had a pregnancy complication in the previous pregnancy or the current pregnancy were 18 times more likely to accompany their partners to ANC compared to those mothers who did not have a pregnancy complication in their previous or current pregnancies (OR = 17.99; 95% CI: 5.62–66.72; p = 0). Mothers with one child were significantly less likely to have their partner accompany them to ANC visits compared to those with two or more children (OR = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.07–0.39; p = 0). Mothers who did receive health education on MPP in ANC had odds of 34.12 times accompanying their spouse compared to those whose spouse did not receive any health education (OR = 34.12; 95% CI: 13.36–95.55; p = 0). Mothers who queued for a long time during the ANC visit (30+ min; OR = 0.15; 95% CI: 0.02–1.14; p = 0.06). Pregnant women who did ask their partners to accompany them to the ANC had an odd of 7.39 times of accompanying their spouses compared to those who did not ask their spouses to accompany them (OR = 7.39; 95% CI: 3.04–19.77). Pregnant mothers who did face challenges involving the spouses in ANC (OR = 4.01; 95% CI: 0.82–22.75; p = 0.10).

| Variable | Category | p-Value | Odds ratio | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Intercept | 0 | 0.13 | 0.05–0.30 |

| Women perspectives on if their spouse should accompany them for ANC after providing finances for the ANC clinic | Agree | Ref | 0.50 | 0.19–1.28 |

| Disagree | 0.15 | |||

| Pregnancy complication | Yes | 0 | 17.99 | 5.62–66.72 |

| No | Ref | |||

| Health education on male partner participation was offered at the ANC | Yes | 0 | 34.12 | 13.36–99.55 |

| No | Ref | |||

| No of children | 1 child | Ref | 0.17 | 0.07–0.39 |

| 2+ children | 0 | |||

| Pregnant mother did face challenge involving the spouse in ANC | Yes | 0.10 | 4.01 | 0.82–22.75 |

| No | Ref | |||

| Pregnant woman did ask the partner to accompany her to ANC | Yes | 0 | 7.39 | 3.04–19.77 |

| No | Ref | |||

| Long queue during ANC visit | Yes | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.02–1.14 |

| No | Ref | |||

4. Discussion

This study reports a low prevalence of MPP in ANC at 29% in a level 4 hospital in eastern Kenya. These results are consistent with studies done in several areas like the Bumula sub-county in Kenya, which show 18% of MPP [42] and 26.2% in Nairobi Kenya [48]. However, this study reported lower MPP in ANC than what has been documented in other studies like the 86.8% in Rwanda [11]. Variation from the study done in Rwanda may be because Rwanda already has a strong national policy in place that promotes MPP in ANC, a well-developed network of male community health workers who champion the integration of men in increasing health-seeking behavior, and effective training and sensitization of healthcare providers [49, 50]. Factors that contributed to the low MPP in this study include health education and women’s perspective that their partners should not accompany them to ANC after providing finances mothers’ request to their partners to accompany them to ANC. A significant correlation has been observed between the probability of a spouse accompanying a pregnant mother to the ANC clinics and health education. The OR of 34.12 (95% CI: 13.36–99.55) indicates that men are much more likely to attend ANC visits when health education is given. This result is consistent with a community-based survey done in Asmara Eriteria in 2019 [51], which highlighted that the male partners’ knowledge of MPP increased the probability of MPP. This emphasizes how vital health professionals are in teaching couples the value of participating together in ANC to enhance the outcomes for mothers and newborns. Therefore, programs that inform both couples about the advantages of male involvement may be a key tactic in raising MPP. While health care workers who did give health education on the importance of MPP in ANC was 27.6%, 80% of those who did receive health education from their partners did participate in ANC. This highlights the potential impact of the health education conducted by healthcare staff on attaining MPP in ANC. Findings from this study did show that health education did contribute to high MPP and the importance of health care workers’ practices in shaping MPP in ANC. Health education can help to promote shared responsibility, informed decision-making, and potentially better pregnancy planning outcomes.

MPP in ANC has shown improved outcomes in the number of ANC visits pregnant mothers have. Mothers who were not accompanied by their partners attended fewer ANC visits than the recommended minimum of four visits. These results are consistent with the study done in Mwanza City, Tanzania, that did show that male partner attendance in ANC led to a higher frequency of ANC attendance by pregnant mothers [52]. From this study, it is evident that health education can help increase MPP in ANC. The study has shown that target health information intervention has a positive correlation with greater willingness of the male partner to participate in ANC. Women who had a discussion with their spouse on the importance or the need for them to accompany them for the ANC visit did have a high MPP compared to those who did not discuss it with their spouses (OR = 7.39; 95% CI: 3.04–19.77). Having a conversation with a partner on attending the ANC clinic leads to a shared decision regarding pregnancy care leading to a sense of shared responsibility which can increase MPP in ANC. This further demonstrates the importance of HCW to educate and promote the MPP among women during their first encounter with the ANC. These findings are similar to a study done in Mozambique which showed that a couple’s increased communication and joint decision-making led to an increase in institutional delivery and MPP [53]. Pregnancy complications did play a part in the increase of MPP in ANC in this study with (OR = 17.99; 95% CI: 5.62–66.72; p = 0). This is evident that if the expectant mother had something that required urgent and immediate attention then the partner was highly likely to participate to offer any form of support that the partner required. These findings are in line with research conducted in Ghana which showed that women with complications were more inclined to have their husbands attend ANC with them [54] and a study done in India that did show men who had knowledge and were aware of pregnancy complications had a high chance of MPP in ANC [55]. The men require education on the importance of ANC whether their spouses have experienced complications in the past or not. Quality and adequate ANC visits improve the pregnancy outcome for both the mother and newborn [4].

In contrast to previous studies that primarily focused on socioeconomic determinants, this study emphasizes the role of healthcare provider-led education and partner communication as critical factors influencing MPP. It also highlights the link between pregnancy complications and MPP, further supporting the need for targeted interventions to encourage male participation in ANC, even in nonobstetric pregnancies. These findings contribute to policy discussions on strengthening male-inclusive ANC programs to improve maternal and newborn health outcomes. This study builds on previous research by providing additional evidence on the low prevalence of MPP in Kenya and reaffirming the importance of health education as a key driver of MPP.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

MPP in ANC is generally low at 29% in Kangundo sub-county, Machakos county, Kenya. The significant predictors of MPP during routine ANC clinics were health education, pregnancy complications, and pregnant mothers’ request to their male partners to accompany them to ANC. Health facilities should design target health education programs aimed at increasing MPP. This includes the provision of health education services to women seeking ANC clinics at the facility and the community level during community outreaches. This will ensure that the community understands the role men play in the health of the mother and the child and finally healthcare professionals can actively encourage males to participate in ANC services by creating a friendly environment.

6. Limitations

Despite the valuable information obtained, this study had several limitations. First, because the study was limited to a single level 4 hospital in eastern Kenya, its findings cannot be applied to other areas with distinct sociocultural and healthcare contexts. Furthermore, because the study used self-reported data, it may be susceptible to social desirability bias or recollection bias, where participants may have overreported MPP as a result of perceived social expectations. Third, although health education was found to be a significant predictor of MPP, the study did not evaluate the precise nature, frequency, or quality of health education sessions given to male partners, which would have affected how well the intervention worked. To evaluate the long-term effects of health education interventions on MPP, future research should examine these elements more thoroughly and take longitudinal studies into account.

Nomenclature

-

- MCH:

-

- Maternal child health

-

- ANC:

-

- Antenatal care

-

- WHO:

-

- World Health Organization

-

- KNBS:

-

- Kenya National Bureau Of Statistics

-

- KDHS:

-

- Kenya Demographic And Health Survey

-

- FP:

-

- Family planning

-

- HIV:

-

- Human immunodeficiency virus

-

- NACOSTI:

-

- National Commission For Science, Technology, And Innovation

-

- NO.:

-

- Number

-

- HCW:

-

- Healthcare worker

-

- MPP:

-

- Male partner participation

-

- MOH:

-

- Ministry Of Health

-

- OR:

-

- Odds ratios.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Wangari Mutuku designed the study, collected, organized, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. John Kariuki and Atei Kerochi designed the study, conducted data analysis, proofread the manuscript, and assisted in organizing the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted without any financial support from external funding bodies. The authors did not receive any grants, sponsorships, or financial assistance from any organization, institution, or funding agency for the design, data collection, analysis, or publication of this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Machakos County Government Ministry of Health which allowed us to use their facilities to carry out this research and to the participants that did take part in the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request.