Health Workers’ Job Satisfaction and Associated Factors at Public Primary Healthcare Centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

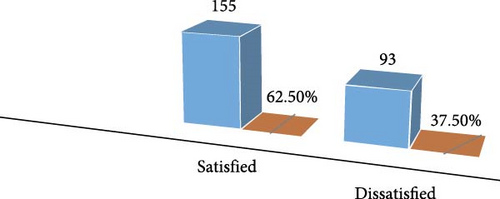

This study investigates health workers’ job satisfaction and its associated factors at public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland. The study aims to understand the levels of job satisfaction among health workers and identify the organizational and individual factors that contribute to their satisfaction. The research was conducted using a cross-sectional survey design, with data collected from 248 healthcare workers in 13 public health centers from 651 professionals in 26 healthy centers from November 15, 2023, to June 12, 2024. The sample is selected using simple random sampling and convenient sampling techniques of health centers and participants. Data were collected with a pretested administered questionnaire. Data were entered into SPSS and analyzed using Stata 17 software. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was used. Statistical significance was determined by considering p-values below 0.05. The results showed that a total of 651 selected from 248 participants were involved in the study. The overall level of job satisfaction among healthcare workers was 62.50% of respondents reported being satisfied, while 37.50% indicated being dissatisfied. While workers aged 31–40 had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.32 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.13–0.77, p ≤ 0.011), a satisfied salary (AOR = 7.10, 95% CI = 3.19–15.7, p ≤ 0.001), being a midwife or medical doctor, was significantly associated with higher job satisfaction (AOR = 5.38, 95% CI = 1.31–22.0, p ≤ 0.019; AOR = 17.3, 95% CI = 2.16–138, p ≤ 0.007), respectively. A satisfied professional type is also significantly associated with higher job satisfaction (AOR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.14–5.60, p ≤ 0.021). The findings of this study recommend that the age group of 31–40 has a satisfied salary, professional type (midwives and medical doctors), and satisfied professional type to enhance the job satisfaction of healthcare workers further.

1. Introduction

Job satisfaction among healthcare workers significantly influences their personal well-being, quality of healthcare services, and overall performance, thereby impacting the quality of care in public health centers [1, 2]. Studies have consistently demonstrated a strong correlation between job satisfaction and healthcare outcomes [3]. Satisfied healthcare professionals tend to be more engaged, productive, and committed to their work, improving patient care and reducing turnover rates [4].

Globally, as sequences, studies have consistently highlighted the need to address job dissatisfaction among healthcare professionals. For instance, a study in Pakistan found the overall satisfaction rate is only 41%, while 45% are somewhat satisfied, and 14% of professionals are dissatisfied with their jobs [5]. Another study in China showed that the average overall job satisfaction score of Chinese community health workers was 67.17% in Shenyang and 69.95% in Benxi. It reinforced the evidence that stress and burnout are essential predictors of internal and external job satisfaction [6]. Additionally, work stress, work–family conflict, and doctor–patient relationships were found to have a significant impact on job satisfaction [7].

Job satisfaction plays a crucial role in shaping healthcare professionals’ attitudes, motivation, and commitment [8]. A study at the Tilganga Eye Center found that 76% of healthcare professionals were satisfied with their current jobs, with variables such as responsibility, opportunity for development, staff relations, and patient care significantly influencing job satisfaction [9]. Age, gender, educational background, and professional experience can also affect job satisfaction [10]. Organizational factors and poor working conditions were strongly associated with job dissatisfaction among public health professionals [5]. A study conducted in Israel among public health nurses found job satisfaction related to working with a professional team, professional responsibility, and autonomy. However, nurses expressed dissatisfaction with salary, workload, and working environment [11].

Any organization that wants to succeed needs an effective supervisor, and job satisfaction refers to how happy an individual is with his or her work [12]. Supervisor behavior and job satisfaction were significantly (positively) correlated with organizational cultures, and job satisfaction was significantly (positively) correlated with supervisor behavior [13].

In African countries, job satisfaction among healthcare professionals is low due to discrepancy factors [14]. There is a yearly deficit in qualified health professionals, with the most significant deficit recorded in Africa due to financial barriers, lack of resources, heavy workloads, inadequate salaries, and ineffective communication between staff and leadership [15, 16]. Boosting healthcare professionals’ job satisfaction is key to improving performance, services, staff motivation, retention, and overall healthcare system functionality in low- and middle-income countries [17, 18].

In Ethiopia, ensuring job satisfaction among healthcare providers is a significant challenge problem. Job satisfaction is an employee’s emotional response to various work-related factors, allowing him to find joy, comfort, confidence, reward, and personal growth, and different positive opportunities, including promotion movement, recognition, and evaluation, are carried out according to a monetary value reward model, and the job satisfaction rate among health professionals in the Western Amhara region was 31.7%. Essential predictors for job satisfaction included the presence of health professionals’ reference manual/guide, alcohol consumption, workload, experience, educational status, and professional types [19, 20]. The job satisfaction of healthcare professionals plays a crucial role in enhancing their performance, optimizing healthcare services, and elevating patient satisfaction [14]. The job satisfaction of healthcare professionals working in public and private hospitals in Bahir Dar city was 29.0% in public hospitals and 81.23% in private hospitals [21]. The rate of job satisfaction among nurses in Morocco was 79.3% [22] and in Uganda, at Arua Regional Referral Hospital, was 60.7% (fair), and variables linked to job satisfaction encompassed the age, gender, religion, duration in practice, recognition, autonomy, coworker aspects, promotion, and supervision [23].

Hence, there are more definitions of job satisfaction globally and regionally, and this study adopted the following definition: job satisfaction is defined as how people feel about their jobs [24]. Furthermore, studies in Addis Ababa reported 53.8% [25], Eastern Ethiopia reported 38.5% [16], and Sengerema District in Mwanza, Tanzania, reported 51.7% [26]. Additionally, this study showed that job satisfaction findings conducted in different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa indicated that 52.1% of health workers in South Africa were satisfied with their jobs compared to 71% in Malawi and 82.6% in Tanzania [18]. In Kathmandu, Nepal, the satisfaction rate was 76% [9], and in Vientiane capital, it was 79.88% [27].

Several studies have investigated job satisfaction among healthcare workers, but there is still a need for further research to understand the specific factors associated with job satisfaction in public healthcare centers. Moreover, the context of public healthcare centers presents unique challenges and opportunities that may contribute to job satisfaction. Public centers often operate under different financial models, organizational structures, and management practices, which can impact health workers’ work environments and job satisfaction [28]. To our knowledge, previous studies have not yet been conducted on this topic, and no other studies in Somaliland have explored the comparison of healthcare workers’ job satisfaction. Therefore, there is a need to investigate the level of job satisfaction among health workers at public health centers and explore the factors associated with their job satisfaction to address and identify the association between critical individual factors such as education level, work experience, and professional type, alongside organizational elements such as relationships with coworkers, supervisors, and salary.

Understanding the factors associated with job satisfaction among health workers that hinder job satisfaction is crucial in creating a conducive work environment and improving the overall well-being of health workers. Identifying these factors makes it possible to develop interventions and strategies to enhance job satisfaction and improve the quality of healthcare services provided by public health centers. Consequently, the purpose of this study was to examine the overall job satisfaction levels and associated factors at public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland. The study was identifying the organizational and individual factors that contribute to their satisfaction.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Design

The study was carried out in Hargeisa, Somaliland, from November 15, 2023, to June 12, 2024. Hargeisa is the capital city of Somaliland region and is located in the western region. It is also the largest city in the country. A quantitative cross-sectional research design was used to assess healthcare workers’ overall job satisfaction levels and associated factors at public primary healthcare centers.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Before the commencement of the study, the study protocol was examined and approved; an official letter was received from the Amoud University Ethical Clearance Board, School of Postgraduate Studies and Research. The Ethics Review Committee, overseen by the Regional Health Director, approved the proposal, considering verbal consent adequate for this study. A collaborative letter was obtained from the regional Health office and distributed to selected healthcare facilities. Before data collection, verbal consent was secured from every participant. Protective measures were enacted to maintain data confidentiality and secrecy. Additionally, participants were informed of their ability to withdraw from the study at any point.

2.3. Study Population and Sample

The study population comprises all the registered medical professionals working in public primary healthcare centers across Hargeisa City, who receive their salaries from either the Ministry of Health or the respective health center under investigation. Conversely, individuals failing to meet these criteria will be excluded from the study. A total of 651 healthcare providers, including doctors, nurses, midwives, technicians, and other health workers, both full-time and part-time, were included in the sampling procedures from 26 public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa. The population of registered professionals in Hargeisa’s public primary care centers was 651. Slovin’s formula, , with a margin of error of 5%, was used to select 248 participants. A simple random sampling method was employed to select 13 of the 26 health centers in the study. Simple random sampling ensures unbiased representation across diverse public healthcare centers in Hargeisa, promoting fairness and reducing systematic biases. Convenience sampling was utilized for selecting the participants due to the varying shifts and working days of registered health workers, allowing for the selection of participants who were readily available and accessible. This method accommodates their schedules, ensuring practicality while aiming for inclusivity in participant selection despite potential biases. By combining simple random sampling and convenience sampling, the aim was to achieve a balance between randomness and practicality, ensuring both representativeness and feasibility in data collection.

2.4. Study Variables

The outcome variable in this study is job satisfaction, which is measured as either satisfied or dissatisfied. Job satisfaction pertains to the degree of satisfaction and how people feel about their jobs [24]. The predictor variables in this study can be categorized into three groups: background characteristics, individual factors, and organizational factors. Background characteristics are gender, marital status, and age, which serve as predictors in the study. Gender distinguishes male and female healthcare workers, while marital status indicates whether they are single or married. Age provides insights into potential variations in job satisfaction based on life stage or experience. Additional predictors include individual factors, including education level, work experience, and professional type. Education level reflects the highest degree attained, such as a bachelor’s or postgraduate qualification. Work experience signifies the number of years employed in the current position or within the healthcare sector. Professional type differentiates between various healthcare professions, such as midwives, medical doctors, or specialized roles. Organizational factors, also considered predictors, encompass coworkers, supervisors, and salary. Coworkers represent interactions and relationships within the healthcare setting. Supervisors provide guidance, support, and feedback to healthcare

2.5. Data Collection Instrument and Data Analysis

The study utilized primary data gathered using a self-administered, pretested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire included sections on job satisfaction levels, organizational factors, and individual factors. The investigator personally distributed these questionnaires to the appropriate participants. A pilot study was conducted to assess the instrument’s feasibility, and content validation and reliability tests were performed. Job satisfaction was measured using an 18-item scale. The instrument was regarded as valid when the average was at least 0.7. The reliability statistics of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicated the internal consistency of the scale value was 0.753, suggesting moderate reliability. The collected data were coded using a self-administered structured questionnaire and entered into the SPSS software. Subsequently, the data were exported to Stata 17 for further analysis.

Here, logit(p) corresponds to the natural logarithm of the odds of job satisfaction relative to job dissatisfaction. The coefficients (β0, β1, β2, …, β9) estimate the impact of each predictor variable on the log odds of job satisfaction. By exponentiation of these coefficients, odds ratios are obtained, which indicate whether a variable increases or decreases the likelihood of job satisfaction. Logistic regression was chosen as the analysis method in this study for several reasons. Firstly, the binary nature of the outcome variable, job satisfaction (satisfied or dissatisfied), makes logistic regression an appropriate choice. Secondly, logistic regression allows for simultaneous examination of multiple predictor variables and their joint effects on the outcome, facilitating understanding of the relative contribution of different factors to job satisfaction. Lastly, logistic regression provides statistical significance testing and odds ratio estimation, enabling the identification and quantification of significant predictors’ impact on job satisfaction.

3. Results

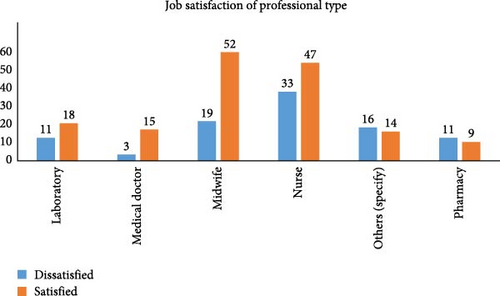

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall level of job satisfaction was moderate. Over 62.5% of respondents reported being satisfied with their jobs, while the remaining 37.5% indicated dissatisfaction. This shows a high dissatisfaction rate in healthcare centers, which needs to be identified in this study. Figure 2 also illustrates the job satisfaction levels of various health professionals. The data reveal a range of satisfaction across different roles; out of the 29 laboratory technicians, 11 (38%) were dissatisfied, while 18 (62%) were satisfied. The figure also showed that out of the 15 medical doctors surveyed, 3 (20%) were dissatisfied and 12 (80%) were satisfied. Among 71 midwives, 19 (27%) reported dissatisfaction, compared to 52 (73%) who were satisfied. Moreover, 33 out of 80 nurses (41%) expressed dissatisfaction, while 47 (59%) were satisfied. The 11 out of 20 pharmacists (55%) were dissatisfied, with 9 (45%) reporting satisfaction. Other professionals category showed that 16 out of 30 (53%) were dissatisfied, while 14 (47%) were satisfied. This figure highlights the variations in job satisfaction across different healthcare professions.

The results of the univariate analysis of the background characteristics, organization factors, and individual factors of the respondents are presented in Table 1, respectively. The results of the univariate analysis of organizational factors show a total of 248 healthcare workers participated in the study. The majority of the participants were female 202 (81.5%), while the male were 46 (18.55%). In the study, more of the participants were single 161 (64.92%) than those married with percentages of 87 (35.08%). In terms of age, for the majority participants, 164 (66.13%) were ≤30 years old, followed by 68 respondents aged 31–40 (27.42%) and 16 who were ≥41 (6.45%).

| Background characteristics | n = 248 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 46 | 18.55 |

| Female | 202 | 81.45 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 161 | 64.92 |

| Married | 87 | 35.08 |

| Age | ||

| ≤30 | 164 | 66.13 |

| 31–40 | 68 | 27.42 |

| ≥41 | 16 | 6.45 |

| Organizational factors | ||

| Coworker relationship | ||

| Poor | 16 | 6.45 |

| Good | 232 | 93.55 |

| Collaboration coworkers | ||

| Never | 40 | 16.13 |

| Frequently | 208 | 83.87 |

| Supportive coworkers | ||

| No | 23 | 9.27 |

| Yes | 225 | 90.73 |

| Communication supervisors | ||

| Poor | 16 | 6.45 |

| Good | 232 | 93.55 |

| Supervisors guidance | ||

| No | 40 | 16.13 |

| Yes | 208 | 83.87 |

| Supportiveness supervisors | ||

| Poor | 51 | 20.56 |

| Good | 197 | 79.44 |

| Satisfied salary | ||

| Dissatisfied | 144 | 58.06 |

| Satisfied | 104 | 41.94 |

| Competitive salary | ||

| No | 104 | 41.94 |

| Yes | 144 | 58.06 |

| Fairness salary | ||

| Unfair | 89 | 35.89 |

| Fair | 159 | 64.11 |

| Individual factors | ||

| Years of work experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 61 | 24.60 |

| 2–5 years | 117 | 47.18 |

| 6–10 years | 38 | 15.32 |

| More than 10 years | 32 | 12.90 |

| Work experience positive contribution | ||

| No | 31 | 12.50 |

| Yes | 217 | 87.50 |

| Satisfied professional type | ||

| Satisfied | 182 | 73.39 |

| Dissatisfied | 66 | 26.61 |

| Level of education | ||

| High school | 32 | 12.90 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 191 | 77.02 |

| Master’s degree | 22 | 8.87 |

| Doctorate/PhD | s3 | 1.21 |

| Educational relevant job | ||

| Yes | 214 | 86.29 |

| No | 34 | 13.71 |

The results of the univariate analysis of organizational factors are presented in Table 1. The survey findings reveal that 93.55% of respondents rated their relationship with coworkers as good and 83.87% reported frequent collaboration or teamwork with their coworkers. Furthermore, 90.73% of participants indicated that they receive the necessary support from their coworkers to achieve work goals. In terms of supervisor, 89.52% of respondents perceived effective communication from supervisors, while 83.87% reported receiving clear expectations and guidance. However, only 79.44% felt that supervisors were supportive in addressing concerns or challenges. Regarding salary, 58.06% expressed dissatisfaction with their current salary, and 41.94% believed their salary was not competitive compared to others in similar positions. Additionally, 35.89% considered the salary and benefits provided by their organization to be unfair. These statistics underscore the need for improvement in coworker relationships, supervisor supportiveness, and addressing salary-related concerns to enhance organizational factors and workers satisfaction.

Table 1 also presents the univariate analysis of individual factors. Work experience analysis reveals that many respondents (47.18%) reported having 2–5 years of experience. Notably, a significant percentage of respondents (87.50%) perceived their work experience as a positive contribution to their job satisfaction. Examining professional types, the largest group consisted of nurses (32.26%), closely followed by midwives (28.63%). When assessing job satisfaction within their respective professional types, most respondents (73.39%) reported being satisfied with their professional situation, while a smaller portion (26.61%) expressed dissatisfaction. In terms of educational background, the highest percentage of respondents (77.02%) held a bachelor’s degree. Furthermore, most respondents (86.29%) believed that their educational background was relevant and valuable to their current job, while the remaining (13.71%) held a different perspective.

More analysis has been applied to identify the correlation between health workers’ job satisfaction and associated factors. Table 2 presents the results of a Pearson χ2 analysis conducted to examine the relationship between various factors and job satisfaction among health workers at public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland. Regarding background characteristics, there is no significant relationship between gender and job satisfaction (χ2 = 0.0641, p ≤ 0.800). However, marital status shows a marginally significant association with job satisfaction (χ2 = 3.0701, p ≤ 0.080). Age is significantly related to job satisfaction (χ2 = 11.2367, p ≤ 0.004). Coworker relationship does not have a significant impact on job satisfaction (χ2 = 2.5655, p ≤ 0.109). However, collaboration with coworkers (χ2 = 17.7248, p ≤ 0.001) and having supportive from coworkers (χ2 = 11.1213, p ≤ 0.001) are significantly related to higher job satisfaction. Good communication with supervisors is associated with greater job satisfaction (χ2 = 7.1610, p ≤ 0.007), while supervisors’ guidance (χ2 = 3.1795, p ≤ 0.075) and supportiveness of supervisors (χ2 = 1.5814, p ≤ 0.209) do not significantly impact job satisfaction. Satisfied salary (χ2 = 31.2247, p ≤ 0.001), having a competitive salary (χ2 = 7.0655, p ≤ 0.008), and perceiving the salary as fair (χ2 = 3.2819, p ≤ 0.070) are all significantly associated with higher job satisfaction. Years of work experience (χ2 = 0.3571, p ≤ 0.949) and level of education (χ2 = 5.0711, p ≤ 0.167) do not significantly affect job satisfaction. However, perceiving work experience as a positive contribution (χ2 = 6.3926, p ≤ 0.011), having a satisfying professional type (χ2 = 28.7406, p ≤ 0.001), and having an educationally relevant job (χ2 = 21.8233, p ≤ 0.001) are all significantly associated with higher job satisfaction.

| Variable | Category | Job satisfaction | Pearson χ2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied | Dissatisfied | ||||

| Gender | — | — | — | 0.0641 | ≤0.800 |

| Male | 28 | 18 | — | — | |

| Female | 127 | 75 | — | — | |

| Marital status | — | — | — | 3.0701 | ≤0.080 |

| Single | 107 | 54 | — | — | |

| Married | 48 | 39 | — | — | |

| Age | — | — | — | 11.2367 | ≤0.004 ∗ |

| ≤30 | 114 | 50 | — | — | |

| 31–40 | 35 | 33 | — | — | |

| ≥41 | 6 | 10 | — | — | |

| Coworker relationship | — | — | — | 2.5655 | ≤0.109 |

| Poor | 7 | 9 | — | — | |

| Good | 148 | 84 | — | — | |

| Collaboration coworkers | — | — | — | 17.7248 | ≤0.001 ∗ |

| Never | 17 | 23 | — | — | |

| Frequently | 138 | 70 | — | — | |

| Supportive co workers | — | — | — | 11.1213 | ≤0.001 ∗ |

| No | 7 | 16 | — | — | |

| Yes | 148 | 77 | — | — | |

| Communication supervisors | — | — | — | 7.1610 | ≤0.007 ∗ |

| Poor | 10 | 16 | — | — | |

| Good | 145 | 77 | — | — | |

| Supervisors guidance | — | — | — | 3.1795 | ≤0.075 |

| No | 20 | 20 | 1 | — | |

| Yes | 135 | 73 | — | — | |

| Supportiveness supervisors | — | — | — | 1.5814 | ≤0.209 |

| Poor | 28 | 23 | — | — | |

| Good | 127 | 70 | — | — | |

| Satisfied salary | — | — | — | 31.2247 | ≤0.001 ∗ |

| Dissatisfied | 70 | 74 | — | — | |

| Satisfied | 85 | 19 | — | — | |

| Competitive salary | — | — | — | 7.0655 | ≤0.008 ∗ |

| No | 55 | 49 | — | — | |

| Yes | 100 | 44 | — | — | |

| Fairness salary | — | — | — | 3.2819 | ≤ 0.070 |

| Unfair | 49 | 40 | — | — | |

| Fair | 106 | 53 | — | — | |

| Years of work experience | — | — | — | 0.3571 | ≤0.949 |

| Less than 1 year | 37 | 24 | — | — | |

| 2–5 years | 75 | 42 | — | — | |

| 6–10 years | 24 | 14 | — | — | |

| More than 10 years | 19 | 13 | — | — | |

| Work experience positive contribution | — | — | — | 6.3926 | ≤0.011 ∗ |

| No | 13 | 18 | — | — | |

| Yes | 142 | 75 | — | — | |

| Professional type | — | — | — | 13.1318 | ≤0.022 ∗ |

| Pharmacy | 9 | 11 | — | — | |

| Laboratory | 18 | 11 | — | — | |

| Nurse | 47 | 33 | — | — | |

| Midwife | 52 | 19 | — | — | |

| Medical doctor | 15 | 3 | — | — | |

| Others | 1 | 16 | — | — | |

| Satisfied professional type | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | — | 28.7406 | ≤0.001 ∗ | |

| Dissatisfied | 26 | 40 | — | — | |

| Satisfied | 129 | 53 | — | — | |

| Level of education | — | — | — | 5.0711 | ≤0.167 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 20 | 12 | — | — | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 121 | 70 | — | — | |

| Master’s degree | 14 | 8 | — | — | |

| Doctorate/PhD | 0 | 3 | — | — | |

| Educational relevant job | — | — | — | 21.8233 | ≤0.001 ∗ |

| No | 9 | 25 | — | — | |

| Yes | 146 | 68 | — | — | |

- ∗Indicates statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

To further explore the factors associated with healthy job satisfaction among workers, we employed multivariable logistic regression analysis in addition to the other statistical methods used in this study. In the bivariate analyses, several variables met the selection criteria (p-value < 0.05), including age, collaboration coworkers, supportive coworkers, communication supervisors, satisfied salary, competitive salary, work experience positive contribution, professional type, satisfied professional type, and educational relevant job. These variables were then included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis as depicted in Table 3. After conducting the analysis, the following factors were identified as significant for the job satisfaction of health workers. Participants aged 31–40 had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 0.32 which showed a significant association with lower job satisfaction compared to those aged ≤30 (AOR = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.13–0.77, p ≤ 0.011 ∗). However, participants with a satisfied salary exhibited significantly higher job satisfaction compared to those with a dissatisfied salary (AOR = 7.10, 95% CI = 3.19–15.7, p ≤ 0.001 ∗). In terms of professional type, the midwife profession (AOR = 5.38, 95% CI = 1.31–22.0, p ≤ 0.019 ∗) and the medical doctor profession (AOR = 17.3, 95% CI = 2.16–138, p ≤ 0.007 ∗) were significantly associated with higher job satisfaction. Furthermore, participants with a satisfied professional type had significantly higher job satisfaction compared to those with a dissatisfied professional type (AOR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.14–5.60, p ≤ 0.021 ∗).

| Variable | Category | Job satisfaction | AOR 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied | Dissatisfied | ||||

| Age | ≤30 | 114 | 50 | 1 | — |

| 31–40 | 35 | 33 | 0.32 (0.130.77) | ≤0.011 ∗ | |

| ≥41 | 6 | 10 | 0.34 (0.07, 1.61) | ≤0.176 | |

| Collaboration coworkers | Never | 17 | 23 | 1 | — |

| Frequently | 138 | 70 | 1.79 (0.67, 4.76) | ≤0.243 | |

| Supportive coworkers | No | 7 | 16 | 1 | — |

| Yes | 148 | 77 | 1.05 (0.24, 4.59) | ≤0.07 | |

| Communication supervisors | Poor | 10 | 16 | 1 | — |

| Good | 145 | 77 | 3.38 (0.91, 12.5) | ≤0.068 | |

| Supervisors guidance | No | 20 | 20 | 1 | — |

| Yes | 135 | 73 | 0.75 (0.23, 2.39) | ≤0.635 | |

| Satisfied salary | Dissatisfied | 70 | 74 | 1 | — |

| Satisfied | 85 | 19 | 7.10 (3.19, 15.7) | ≤0.001 ∗ | |

| Competitive salary | No | 55 | 49 | 1 | — |

| Yes | 100 | 44 | 1.29 (0.62, 2.71) | ≤0.70 | |

| Fairness salary | Unfair | 49 | 40 | 1 | — |

| Fair | 106 | 53 | 1.07 (0.52, 2.18) | ≤0.840 | |

| Work experience positive contribution | No | 13 | 18 | 1 | — |

| Yes | 142 | 75 | 1.28 (0.44, 3.72) | ≤0.639 | |

| Professional type | Pharmacy | 9 | 11 | 1 | — |

| Laboratory | 18 | 11 | 3.60 (0.83, 15.4) | ≤0.085 | |

| Nurse | 47 | 33 | 2.45 (0.67, 8.96) | ≤0.173 | |

| Midwife | 52 | 19 | 5.38 (1.31, 22.0) | ≤0.019 ∗ | |

| Medical doctor | 15 | 3 | 17.3 (2.16, 138) | ≤0.007 ∗ | |

| Others | 1 | 16 | 3.09 (0.69, 13.8) | ≤0.138 | |

| Satisfied professional type | Dissatisfied | 26 | 40 | 1 | — |

| Satisfied | 129 | 53 | 2.53 (1.14, 5.60) | ≤0.021 ∗ | |

| Educational relevant job | No | 9 | 25 | 1 | — |

| Yes | 146 | 68 | 3.00 (0.90, 10.0) | ≤0.72 | |

- Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

- ∗An AOR quantifies the association between an exposure and an outcome, accounting for confounders. AOR > 1 indicates increased odds, AOR < 1 indicates decreased odds, and AOR = 1 indicates no association.

4. Discussion

The overall job satisfaction on the health workers and associated factors at public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland, was 62.50% of respondents reported being satisfied, while 37.50% indicated being dissatisfied. The bivariate analysis notable findings include a significant association between ages, collaboration with coworkers, supportive coworkers, communication with supervisors, satisfaction with salary, competitiveness of salary, work experience positive contribution, professional type, satisfaction with professional type, and educational relevance of the job with job satisfaction. Multivariable analysis age, satisfied salary, and professional type were found to be a significant association of job satisfaction. When comparing these findings with other relevant study, it is evident that certain differences exist.

Earlier research conducted among health workers in Ethiopia, specifically in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia, reported job satisfaction rates of 55.2% [21]; 53.8% in Addis Ababa [25]; 38.5% in Eastern Ethiopia [16]; 31.7% in the Western Amhara [20]; 60.7% in West Nile, Uganda [23]; and 51.7% in Sengerema District, Mwanza, Tanzania [26]; and Pakistan 41% [5]. Nevertheless, the present study indicated a higher level of job satisfaction compared to the aforementioned studies. The researchers emphasized the significance of satisfaction among healthcare professionals, as job satisfaction has implications for variables such as the presence of health professionals’ reference manual/guide, alcohol consumption, workload, experience, educational status, professional types, age, gender, religion, duration in practice, recognition, autonomy, coworker aspects, promotion, supervision, working environments, time pressure, and training.

Moreover, this study revealed that job satisfaction was lower than a study conducted among different categories of health workers in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, with 52.1% of health workers in South Africa being satisfied with their jobs compared to 71% in Malawi and 82.6% in Tanzania [18]; 76% in Kathmandu, Nepal [9]; and 79.88% in Vientiane capital [27]. The potential reasons for this variation could be attributed to differences in sociodemographic characteristics, intrinsic motivators, extrinsic factors, study participants, ethnicity, and organizational structures.

In terms of organizational factors, the current study highlights that health workers with positive coworker relationships, collaboration, and support were very satisfied with their jobs. Similar studies, such as those by [21, 23, 29, 30] and [31] along with [3, 22] and [32] have also shown these patterns. The only differences lie in the study areas, populations under investigation, and study variables. These steady results suggest that positive coworker relationships and collaboration are crucial factors in promoting job satisfaction among healthcare workers.

While this study did not find significance in the support provided by supervisors to healthcare workers, the research indicates that healthcare workers highly valued effective communication from their supervisors, a factor that holds significance. This importance was closely followed by clear expectations and guidance. These results were substantiated by studies conducted by this researchers [2, 9, 23, 33, 34]. Their research suggests that healthcare workers who have supportive supervisors tend to be more satisfied with their jobs, whereas this study indicates that healthcare workers who receive effective communication from their supervisors experience greater job satisfaction. These differences highlight the variations among these studies.

The study also sheds light on the significance of salary-related factors in job satisfaction. In this study, a participant with a satisfied salary exhibited significantly higher job satisfaction compared to those with a dissatisfied salary, and they believed their salary was not competitive compared to others in similar positions. These results correspond with the studies conducted by different locations [8, 25, 28, 31, 34, 35] where they reported that increased salary significantly enhances job satisfaction. These consistent findings underscore the importance of addressing salary concerns and offering competitive and fair compensation packages to boost job satisfaction among healthcare workers. The variance of these studies are type of analysis, study units, and sample size.

With regard to individual factors, the study examines the influence of work experience and professional type on job satisfaction. Regarding work experience, this study found that a significant portion of respondents perceived their work experience as a positive contribution to their job satisfaction. These findings are in line with the research performed by another place [10, 16, 32]. These consistent findings emphasize the importance of recognizing and valuing the contributions of experienced healthcare workers to enhance their job satisfaction. The differences among these studies lie in the years of experience that healthcare workers possess.

In terms of professional types, the largest group of respondents in this study consisted of nurses (32.26%), followed closely by midwives (28.63%). These results are in conformity with the investigation conducted by Amhara Region [20] where they reported that nursing staff constituted the majority (52.3%), with 56.5% of nursing workers [30]. They also noted that nurses were the predominant group among healthcare professionals. However, it is important to note that job satisfaction varied among professional types. Workers aged 31–40 reported lower satisfaction, while midwives and medical doctors exhibited higher levels. Furthermore, studies from Nepal indicated that professionals aged less than or greater than 35 had the highest job satisfaction [9].

Lastly, the study delves into the significance of educational background on job satisfaction. The majority of respondents in this study held a bachelor’s degree and believed that their educational background was pertinent and beneficial to their current job. These results are consistent with the research reported by Ethiopia and Australia [25, 32] where they discovered that a significant portion of healthcare workers believed their educational background was relevant to their job. They also identified a positive correlation between educational attainment and job satisfaction among healthcare professionals. These consistent findings underscore the importance of education in healthcare professions and its influence on job satisfaction.

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are proposed to improve job satisfaction among healthcare workers in Hargeisa: The study highlights the importance of organizational and individual factors in determining job satisfaction among healthcare workers. By addressing coworker relationships, supervisor supportiveness, salary concerns, work experience recognition, educational relevance, and regularly assessing job satisfaction, public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland, can enhance the overall well-being and job satisfaction of their workforce. A satisfied workforce not only benefits healthcare professionals but also contributes to better patient care outcomes. Therefore, it is crucial for ministry of health and development to prioritize and invest in strategies that promote job satisfaction among their workers by using advanced longitudinal designs to information than this study.

Despite providing valuable insights, this study has several limitations: The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size of 248 healthcare workers, potentially limiting generalizability. The cross-sectional design may not capture changes over time or establish causal relationships. The study’s focus on specific organizational and individual factors may overlook other important variables influencing job satisfaction. Contextual factors unique to Hargeisa may restrict broader applicability. Furthermore, the study could benefit from a deeper contextualization within the specific socioeconomic and cultural environment of Hargeisa, considering factors such as regional healthcare policies, economic conditions, and cultural attitudes toward healthcare professions. Although these factors were not the primary focus of this research, acknowledging their potential impact can enhance the understanding of the results. Additionally, the limited duration of the study and the methods of data analysis utilized could impact the depth and interpretation of the findings. Addressing these limitations in future research could strengthen the study’s validity and relevance in understanding job satisfaction among healthcare workers.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into job satisfaction among healthcare workers at public primary healthcare centers in Hargeisa, Somaliland, highlighting key influencing factors. The findings reveal that 62.5% of respondents were satisfied with their jobs, supporting the hypothesis that healthcare workers generally perceive their job satisfaction positively, consistent with previous studies showing moderate satisfaction levels in similar contexts. Key individual factors associated with job satisfaction included age, professional type, and salary satisfaction, with workers aged 31–40 less likely to be satisfied (AOR = 0.32), while midwives (AOR = 5.38) and medical doctors (AOR = 17.3) exhibited significantly higher satisfaction levels. Salary satisfaction emerged as a critical organizational factor (AOR = 7.10), although coworker relationships and supervisor support, while important in other studies, were not statistically significant here. This research enriches the understanding of healthcare workers’ job satisfaction in Somaliland, emphasizing the importance of both individual and organizational factors and advocating for targeted interventions, particularly in salary improvements and addressing specific professional needs. The findings have significant implications for healthcare organizations and policymakers, suggesting that focusing on salary satisfaction and the needs of specific professional roles can lead to enhanced job satisfaction, improved service delivery, and reduced turnover among healthcare workers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Ridwan A. Mohamed significantly contributed to this research’s conception, design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing. Omran Salih provided valuable supervision and reviewed the work.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt appreciation to the data collectors and supervisors for their prompt submission of the completed questionnaires. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to the Amoud University, Institute of Science in Research, Data Analysis, and Statistical Methods, in Borama, Somaliland, for their invaluable guidance throughout this study. Additionally, the authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all the healthcare workers who actively participated in this research.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author, who can be contacted at [email protected] or [email protected], is able to provide the data used to support the study’s findings upon request.