Social Security Coverage and Related Factors in Mexican Older Adults: Analysis of Three National Surveys From the Mexican Health and Aging Study

Abstract

Aim: This study aims to analyze social security coverage and identify the associated factors that may promote access to healthcare services in three nationally representative surveys of older Mexican adults.

Methods: The present study used data obtained from nationally representative surveys conducted by the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) and comprising three waves undertaken, in 2015, 2018, and 2021, on a sample of 24,081 older adults (19.6% resident in rural areas and 55.2% women). The variables included age, gender, residence, years of education, multimorbidity, marital status, use of glasses, self-reported health (SRH), and social security coverage (insured vs. uninsured). A nominal logistic regression model was used to evaluate the associations between the independent variables and social security coverage.

Results: In the sample, 60.8% (n = 14,644) of the older adults were insured, presenting an increase of 6.7% from 2015 to 2021. By 2021, the variables years of education (odds ratio [OR] = 3.37 [95% confidence interval [CI] 2.74–4.15]), living in an urban area (OR = 4.80 [95% CI 4.24–5.43]), using glasses (OR = 1.47 [95% CI 1.33–1.63]), multimorbidity (OR = 1.36 [95% CI 1.22–1.53]), and with spouse/partner (OR = 1.26 [95% CI 1.13–1.40]) increased the probability of social security coverage in older adults.

Conclusions: In the sample, 60.8% of older adults have access to social security coverage, representing a 6.7% increase on the percentage obtained for the 2015 sample. Identifying the barriers to social security coverage is necessary in order to improve access to the healthcare system and reduce health in equalities for all older Mexican adults.

1. Introduction

An aging population is one of the most significant demographic, medical, and social problems on a global level [1] and is driven by increased life expectancy. With the demographic changes caused by low fertility and mortality rates, life expectancy is predicted to have improved between 2022 and 2050 [2]. The aging process is a social phenomenon that has consequences in most sectors of society, including the use of goods and services, the financial and labor markets, social and family protection systems, and intergenerational relationships.

Data obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) show a global increase in the population aged 60 years and over, which was estimated at one billion in 2020 and is predicted to increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050. Similarly, by 2050, it is predicted that two-thirds of the world population aged 60 years and over will be living in low- to medium-income countries [3]. Mexico is experiencing a process of population aging, wherein the proportion of adults aged 60 years and over in 2024 corresponded to 12.9% of the population, a percentage that is expected to increase to 25% by 2050 [4].

Population aging has considerable effects on the state of health in a society. While aging is not, in and of itself, a health condition, the associated accumulation of a wide variety of exposures and psychological, physical, and social conditions over time does increase the risk of health problems in older adults [5, 6]. Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) result from various genetic, physiological, behavioral, and environmental factors, while the WHO states that they are responsible for 71% of the total number of annual deaths on a global level [7]. Data indicate that, from 1990 to 2022, in Mexico, NCDs and metabolic risk factors were the principal contributors to loss of health for people ≥60 years [8].

NCDs can cause an increase in both demand for healthcare services and treatment costs, as well as having a much greater financial impact on older adults than on younger cohorts of the population [9, 10]. Access to healthcare services involves assisting people to make use of the available healthcare resources to both ensure health prevention and maintain and improve their health [11] and resources which also help to maintain physical function in older adults and improve their qualityof life [12]. Modifiable barriers to access to healthcare services, such as economic, structural, social, cognitive, cultural, and geographic factors, affect access to healthcare and produce adverse effects on both an individual and collective level [13].

In recent years, Mexico has adopted initiatives, via both governmental and nongovernmental organizations, which aim to promote a healthy aging process for older adults and involve both the healthcare and education systems and the wider community [14]. The older adult population in Mexico has fragmented access to medical care, consisting in employment-based social security schemes, public assistance services for the uninsured, and the private sector [15]. A recent study reported that 71% of the Mexican population with healthcare needs had access to medical services and only 32% received treatment in public institutions [16],while evidence from other research indicates that older Mexican adults aged 50 years or over with diabetes and living in rural areas are 77% less likely to be insured [17]. Despite the great importance, for older adults, of accessing the healthcare system, research is limited on the factors affecting such access for the aging population. For example, those older adults who are women, self-report their health as poor, have multimorbidity, are single/separated/divorced, are illiterate, and/or have limited capacity to carry out day-to-day activities experience greater difficulties in accessing healthcare services [10, 18].

As Mexico is experiencing rapid population aging, providing adequate information to studying the factors related to access to healthcare services will assist in reducing inequalities and proposing new strategies for increasing social security coverage in older adults. The present study evaluates the recent trends in social security coverage and analyzes associated factors that have emerged over the last 6 years, via the examination of a nationally representative sample of the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) providing a perspective on healthcare policy in Mexico. We know that aging is accompanied by a wide variety of progressive changes that increase the prevalence of NCDs in older adults and, consequently, can impact access to health services. Providing adequate information to study these phenomena is of great importance for designing and implementing public policies. Moreover, the study contributes important information for international research efforts focusing on aging and healthcare services. For this reason, the present study aimed to analyze the responses to three nationally representative surveys of Mexican older adults regarding social security coverage and identify the associated factors that may increase their access to healthcare services.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Source

MHAS is one of the largest ongoing longitudinal studies of aging in Latin America, with six waves over 20 years (2001, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2021). MHAS includes demographic data; self-reported health (SRH), in various dimensions (chronic diseases, physical function, perceived global health, depressive symptoms, and functional status); institutional support; life satisfaction; social support and engagement; housing conditions; and economic aspects (health expenditure, health insurance coverage, and income), from a nationally representative sample of adults 50 years and older in urban and rural Mexico [19].

2.2. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The research carried out by the present study adhered to the relevant ethical criteria for research on human subjects and was approved by the corresponding ethics committee (University of Texas Medical Branch and, in Mexico, INEGI and the National Institute of Public Health) (NIH R01AG018016). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants. Data files and documentation are available for public use at https://enasem.org/Home/index_esp.aspx.

2.3. Study Population

The study was conducted on a subsample taken from the MHAS and comprising 24,081 adults aged 65 years and over, which, by year, corresponded to 8167 (year 2015), 7854 (year 2018), and 8060 (year 2021) older adults. The inclusion criteria applied for selecting participants were as follows: being an adult over the age of 65 years; being of either gender; and not having presented missing data in the responses to the questionnaire.

2.4. Independent Variables

The following set of predictor variables were selected to identify the demographic and health-related characteristics within the sample (Table 1): age; gender; marital status; place of residence; years of education; using glasses; SRH; and multimorbidity.

| Variable | 2015 | 2018 | 2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 8167) | (n = 7854) | (n = 8060) | |||||||

| Insured | Uninsured | p | Insured | Uninsured | p | Insured | Uninsured | p | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||||

| Age groups | |||||||||

| 65–74 years | 2896 (61.5) | 2084 (60.2) | 0.001 | 2757 (57.9) | 1709 (55.2) | 0.030 | 2810 (54.3) | 1516 (52.6) | 0.005 |

| 75–84 years | 1438 (30.6) | 1019 (29.4) | 1537 (32.3) | 1040 (33.6) | 1829 (35.3) | 996 (34.6) | |||

| ≥85 years | 372 (7.9) | 358 (10.4) | 465 (9.8) | 346 (11.2) | 540 (10.4) | 369 (12.8) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 2170 (46.1) | 1624 (46.9) | 0.467 | 2107 (44.3) | 1407 (45.5) | 0.301 | 2196 (42.4) | 1285 (44.6) | 0.056 |

| Women | 2536 (53.9) | 1837 (53.1) | 2652 (55.7) | 1688 (54.5) | 2983 (57.6) | 1596 (55.4) | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Without spouse/partner | 1954 (41.5) | 1507 (43.5) | 0.068 | 1948 (40.9) | 1346 (43.5) | 0.025 | 2277 (44.1) | 1346 (47.0) | 0.012 |

| With spouse/partner | 2752 (58.5) | 1954 (56.5) | 2811 (59.1) | 1749 (56.5) | 2886 (55.9) | 1516 (53.0) | |||

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 4346 (92.4) | 2281 (65.9) | <0.001 | 4326 (90.9) | 1977 (63.9) | <0.001 | 4674 (90.3) | 1766 (61.3) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 360 (7.6) | 1180 (34.1) | 433 (9.1) | 1118 (36.1) | 505 (9.7) | 1115 (38.7) | |||

| Years of education | |||||||||

| No education | 703 (14.9) | 1183 (34.2) | <0.001 | 667 (14.0) | 1009 (32.6) | <0.001 | 638 (12.3) | 850 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| 1–9 years | 3379 (71.8) | 2081 (60.1) | 3456 (72.6) | 1921 (62.1) | 3753 (72.5) | 1848 (64.1) | |||

| ≥10 years | 624 (13.3) | 197 (5.7) | 636 (13.4) | 165 (5.3) | 788 (15.2) | 183 (6.4) | |||

| Wear glasses | |||||||||

| No | 1910 (40.6) | 2073 (59.9) | 1739 (36.5) | 1658 (53.6) | 1881 (36.3) | 1539 (53.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2796 (59.4) | 1388 (40.1) | 3020 (63.5) | 1437 (46.4) | 3298 (63.7) | 1342 (46.6) | |||

| Would you say your health is… | |||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 242 (5.1) | 136 (3.9) | <0.001 | 293 (6.2) | 132 (4.3) | <0.001 | 320 (6.2) | 130 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Good | 1117 (23.7) | 673 (19.4) | 1124 (23.6) | 629 (20.3) | 1331 (25.7) | 622 (21.6) | |||

| Fair | 2319 (49.3) | 1691 (48.9) | 2400 (50.4) | 1526 (49.3) | 2589 (50.0) | 1442 (50.0) | |||

| Poor | 1028 (21.8) | 961 (27.8) | 942 (19.8) | 808 (26.1) | 939 (18.1) | 687 (23.9) | |||

| Multimorbidity | |||||||||

| Non-multimorbidity | 3096 (65.8) | 2417 (69.8) | <0.001 | 3252 (68.3) | 2243 (72.5) | <0.001 | 3491 (67.4) | 2158 (74.9) | <0.001 |

| Multimorbidity ≥2 | 1610 (34.2) | 1044 (30.2) | 1507 (31.7) | 852 (27.5) | 1688 (32.6) | 723 (25.1) | |||

- Note: Chi-squared test.

2.5. Dependent Variable: Health Insurance Coverage

Many older adults receive their healthcare via their affiliation to the social security provision provided by the following institutions in Mexico: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS or Mexican Institute of Social Security); Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado (ISSSTE or Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers); Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX or Mexican Petroleum); Secretaria de Defensa Nacional (SEDENA or Ministry of Defense); and the Secretaria de Marina (SEMAR or Ministry of the Navy). Those older adults considered uninsured can access the healthcare institutions that fall outside social security provision, such as the Ministry of Health, the Institute for Health, or the recently abolished Instituto de Salud para elBienestar (INSABI or Institute of Health for Wellbeing) and Seguro Popular (the People’s Insurance), while the other option is private health insurance. In the present study, the variable healthcare coverage was dichotomized into insured/uninsured [17, 20].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 18 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Firstly, the data pertaining to each year of the MHAS (2015, 2018, and 2021) were cross-referenced for the dependent (insured/uninsured) and independent variables. Secondly, the Cochran–Armitage tendency test (which classifies responses as 0/1) was conducted to estimate whether there was a significant percentage increase in access to social security coverage by older adults over the course of the three national surveys. The dependent variable applied was access to social security coverage, while the independent variable was the specific survey year, namely, 2015, 2018, or 2021. Lastly, three nominal logistic regression models were applied to determine the association between the independent variables of interest (gender, age group, marital status, years of education, place of residence, using glasses, and multimorbidity) and the dependent variable of health insurance coverage (insured = 1/uninsured = 0). The odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated, with values of p ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant. The analyses were adjusted to enable the design of complex surveys using Stata version 18. The variance inflation factor (VIF) command and 1/VIF were used after the regression to check for multicollinearity. As a rule of thumb, a variable with a VIF value greater than 10 may require further investigation. The collin command in Stata was then used to evaluate collinearity between variables years of education, place of residence, gender, and age group.

3. Results

In total, 24,081 older adults with an average age of 74.4 (± 7.13) years participated in the survey (MHAS 2015–2021), of whom 55.2% were women, 19.6% lived in rural areas, 55.2% used glasses, 20.6% were illiterate, and 71.9% considered their health to be from regular to poor. The highest prevalence of NCDs in older adults was found for hypertension (53.1%), followed by diabetes (27.3%), rheumatoid arthritis (16.3%), heart disease (11.6%), respiratory disease (6.9%), and cancer (3.2%).

Table 1 presents the relationship between demographic and health characteristics in insured and uninsured older adults for each year surveyed (2015, 2018, and 2021), with an increase observed for the percentage of insured older adults over the three survey years, for example, by age group (75–84 and ≥85 years). Social security coverage was found to be higher in the urban than the rural population, while those with more years of education presented higher levels of social security coverage than those with fewer years and those who used glasses presented higher levels of coverage than those who did not.

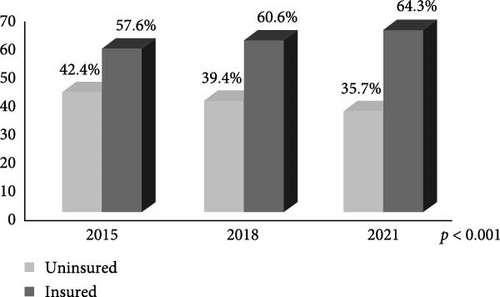

The percentages of insured and uninsured older adults for the entire sample were 60.8% and 29.2%, respectively. For the 2015–2021 period, IMSS was found to have provided healthcare services to ~39.8%, ISSSTE 18.5%, PEMEX 2.5%, and the healthcare institutions outside the social security system 29.2%. Figure 1 presents the percentages of respondents with social security coverage, which correspond to 57.6% (95% CI 56.5–58.7), 60.5% (95% CI 59.5–61.7), and 64.3% (95% CI 63.2–65.3) for the years 2015, 2018, and 2021, respectively. The tendency test found that the percentage of social security coverage has increased, with a positive tendency (z = 8.65; p < 0.001).

3.1. Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 presents the results for the multivariate logistic regression, while the following variables were considered by the multivariate model for 2015, 2018, and 2021: gender; age group; marital status; years of education; place of residence;using glasses; and multimorbidity. In 2015, the variable corresponding to years of education (1–9 years and ≥10 years) increased the probability of access to social security coverage, with respective results of OR = 2.15 times (95% CI 1.91–2.42) and OR = 3.15 (95% CI 2.58–3.84). Living in an urban area, using glasses, presenting multimorbidities, and being married increased the probability of access to social security coverage, with respective results of OR = 5.05 (95% CI 4.42–5.77), OR = 1.60 (95% CI 1.45–1.77), OR = 1.15 (95% CI 1.04–1.27), and OR = 1.18 (95% CI 1.06–1.31).

MHAS 2015 (n = 8167) |

MHAS 2018 (n = 7854) |

MHAS 2021 (n = 8060) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjust OR (95% CI) | p | Adjust OR (95% CI) | p | Adjust OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Gender | Men | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Women | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.825 | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) | 0.397 | 1.08 (0.97–1.21) | 0.135 | |

| Age groups | 65–74 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 75–84 years | 1.22 (1.09–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) | 0.322 | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 0.053 | |

| ≥85 years | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 0.574 | 1.18 (0.99–1.41) | 0.053 | 1.11 (0.93–1.31) | 0.224 | |

| Marital status | Without spouse/partner | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| With spouse/partner | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) | 0.002 | 1.19 (1.06–1.32) | 0.002 | 1.26 (1.13–1.40) | <0.001 | |

| Years of education | No education | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1–9 years | 2.15 (1.91–2.42) | <0.001 | 2.20 (1.95–2.49) | <0.001 | 2.15 (1.89–2.44) | <0.001 | |

| ≥10 years | 3.15 (2.58–3.84) | <0.001 | 3.42 (2.77–4.23) | <0.001 | 3.37 (2.74–4.15) | <0.001 | |

| Place of residence | Rural | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Urban | 5.05 (4.42–5.77) | <0.001 | 4.67 (4.10–5.30) | <0.001 | 4.80 (4.24–5.43) | <0.001 | |

| Wear glasses | No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.60 (1.45–1.77) | <0.001 | 1.51 (1.37–1.68) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.33–1.63) | <0.001 | |

| Multimorbidity | Non-multimorbidity | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Multimorbidity ≥ 2 | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 0.007 | 1.15 (1.03–1.29) | 0.008 | 1.36 (1.22–1.53) | <0.001 | |

- Note: Logistic regression model.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

In 2018, the variables years of education, place of residence, using glasses, multimorbidity, and marital status increased the probability of older adults having access to social security coverage. An increased probability was also observed for 2021, with respective results, for the same variables of OR = 3.37 (95% CI 2.74–4.15), OR = 4.80 (95% CI 4.24–5.43), OR = 1.47 (95% CI 1.33–1.63), OR = 1.36 (95% CI 1.22–1.53), and OR = 1.26 (95% CI 1.13–1.40).

3.2. Checking for Multicollinearity

The VIF values for years of education and place of residence were 1.06 and 1.02, and the tolerance (1/VIF) values were 0.93 and 0.97, respectively. Subsequently, collinearity between the variables sex, years of education, and place of residence was evaluated, and the condition number was obtained, which is a commonly used index of the global instability of the regression coefficients, finding a value of 6.88; therefore, no instability was present.

4. Discussion

The present study found an increase, from 57.6% to 64.3%, in the percentage of respondents with social security coverage for the 2015–2021 period. The percentage of older Mexican adults with coverage in 2021 was 6.7% higher than that observed for 2015. García-Hernández et al., in their analysis of the data obtained by the Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT, or the National Health and Nutrition Survey) for the years 2018, 2021, and 2022, found percentages of 43.3%, 40.8%, 43.8%, respectively, for older adults’ access to the public health system [21]. This finding indicates that the aging population uses healthcare services more than the general population [22]. For this reason, research is required to explore the tendencies in both the need for and coverage provided by healthcare services, in order to then be able to design a national healthy aging strategy that improves access to and quality of care for the older adult population.

Research has reported information on social security coverage and access to healthcare among older adults. For example, Tao et al. reported on the use of medical services [23]. On the other hand, Fan et al. [24] reported that there is inequality in health service utilization exists among the middle-aged and older adults across urban and rural Chinese areas. Finally, among adults in China, it was observed that insured individuals used rehabilitation services more compared to uninsured individuals. Therefore, social security can improve accessibility in the use of health services, as well as strengthen underserved populations in order to improve the effective use of health services and better meet their needs [25].

Life expectancy captures mortality throughout the life cycle and is positively associated with health and well-being. In 2019, life expectancy at birth reached 73.3 years worldwide [26]. In 2023, life expectancy in Mexico is 78.4 years for women and 72.1 years for men. On the other hand, the reductions in highly prevalent infectious diseases, fertility, rapid urbanization, and the increase in unhealthy lifestyles, among other determinants, have accelerated the epidemiological transition and increased the NCDs [8]. NCDs can cause an increase in both demand for healthcare services and treatment costs, as well as having a much greater financial impact on older adults than on younger cohorts of the population [9, 10].

In Mexico, the healthcare system is segmented into national or federal public institutions and private providers and insurers [15]. Formal employees are affiliated to healthcare institutions governed at a federal level and which offer social security and broader medical attention and benefits [15], while informal employees and their dependents are only entitled to use the healthcare institutions that fall outside the social security system [21]. The coverage for the uninsured is overseen by IMSS-Bienestar at a federal level, with the cooperation of state governments [15].

Likewise, health policies have been implemented with the objective of providing health coverage to those in the population without social security coverage, thus ensuring their access to healthcare services. One of these policies was the Seguro Popular, which was reformed in 2019, becoming the INSABI. The purpose set for INSABI is to provide free universal healthcare and address the gaps in both health coverage between urban and rural areas in Mexico’s most remote and marginalized regions. Similarly, the lack of human resources in health and the increase in chronic diseases among the population limit efforts to address health promotion and prevention. Furthermore, the lack of economic resources particularly affects rural areas, where insecurity and lack of infrastructure are problems with a negative impact on the population [15].

The results obtained by the present study for 2015 report that, approximately, 42.4% of older adults in Mexico find themselves in the latter informal situation, as described above, although this percentage fell to 35.7% in 2021. Despite the progress made in increased healthcare coverage for older Mexican adults, the continued strengthening of the nation’s healthcare systems over the short and long term and at both a state and national level is required to cover the needs of older adults. This strengthening will require the improvement of national healthcare policy, the creation of monitoring systems, and increased funding, given the likely increase in life expectancy, the incidence ofNCDs, and, thus, the increased demands placed on healthcare services [27].

Marital status, years of education, place of residence, use of glasses, and the presence of multimorbidity all increased the probability of security coverage for older adults in the three periods surveyed. The finding that being married or in a long-term relationship with a partner increased the possibilities of being insured concurs with the results reported by Pandey et al. [28]. One of the reasons for this is the concept of “matrimonial protection,” in which women function as carers, providing physical and emotional support and improving their spouse’s health [28, 29]. Furthermore, the older adults who are married or in long-term relationships have greater expectations for and express greater satisfaction with their quality of life and social relationships [30]. For the above reasons, marital status may play a fundamental role in the analysis of social security coverage in older Mexican adults.

The present study found that living in an urban area increased the probabilities of access to social security coverage. Urbanization can bring benefits to the general population, such as greater access to healthcare services, higher literacy rates, higher life expectancy, and more opportunities for economic growth than those available for their rural counter parts [31]. Moreover, urban populations are more likely to have access to hospitals and healthcare centers due to the proximity of healthcare resources in these areas [32]. It is of utmost importance that equal health protection is ensured for both the rural and urban older adult populations, given that access to and use of healthcare services are known to improve health conditions and life satisfaction in the aging population [33, 34].

Education plays a fundamental role in the aging process and health, due to the fact that it is one of the most important factors for lifestyle, improving health, and disease prevention. Furthermore, education has been associated with health literacy, a concept involving a person’s knowledge and understanding of their health and how to take good decisions in that regard [35]. In this sense, the results obtained by the present study show that more years of education increase the probabilities of access to health coverage in older Mexican adults. Various studies have shown that a low health literacy level is a predictor of unfavorable health outcomes [36, 37]. For these reasons, research is required on the impact of other factors such as age, gender, comorbidities, and place of residence on health literacy levels in the aging population.

It is known that multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic diseases, increases more in older populations than in other age groups [38, 39]. The literature reports results which indicate that multimorbidity is related to increased mortality, along with the reduction in functional status, greater use and costs of medical treatment (including a high level of medication use), and reduced health-related quality of life [40, 41]. The present study found that older Mexican adults with multimorbidity were 15% more likely to have social security coverage in the years 2015–2018, although, by 2021, this had increased to 36%. Therefore, due to aging, older adults with multimorbidity require integrated healthcare systems that factor in other variables in order to ascertain their relationship with the use of healthcare services.

5. Limitations

Firstly, one of the limitations of the present study was its cross-sectional design, as it prevented cause–effect evaluation and could lead to the presentation of some type of bias. Secondly, the access of older adults to private medical care was not analyzed and potentially recall bias in self-reported variables, particularly for multimorbidity and healthcare access. Thirdly, longitudinal studies are required to explore the effect of factor socioeconomics that could influence social security coverage. On the other hand, the strength of the present study is that it used a large representative sample of older adults in Mexico, which corresponded to three study periods (2015, 2018, and 2021) and which enabled the examination of the relationship between the variables of interest and social security coverage in the population.

6. Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that 60.8% of the sample of older adults had social security coverage, representing an increase of 6.7% from 2015 to 2021. Similarly, the variables examined play an important role in increasing access to social security for older adults. Therefore, the significant findings of the present study can be used to design and generate public health policy that will improve access to the health and welfare systems and reduce health inequalities for all older Mexican adults.

Nomenclature

-

- CI:

-

- Confidence interval

-

- IMSS:

-

- Mexican Institute of Social Security

-

- INEGI:

-

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography

-

- INSABI:

-

- National Health Institute for Wellbeing

-

- ISSSTE:

-

- Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers

-

- MHAS:

-

- Mexican Health and Aging Study

-

- NCDs:

-

- Noncommunicable diseases

-

- OR:

-

- Odds ratio

-

- PEMEX:

-

- Mexican Petroleum

-

- SEDENA:

-

- Ministry of Defense

-

- SEMAR:

-

- Ministry of the Navy

-

- SRH:

-

- Self-reported health

-

- WHO:

-

- World Health Organization

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

The MHAS is partly sponsored by the National Institute of Aging at the US National Institutes of Health and INEGI in Mexico. The authors thank the Public Health Research Laboratory at the Faculty of Higher Studies Iztacala, National Autonomous University of Mexico—particularly for their support with the conceptual design of the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Estudio Nacional de Salud y Envejecimiento en México (ENASEM at https://enasem.org/Home/index_esp.aspx).