Investigating Barriers and Facilitators to Engagement With the National Breast Screening Programme Among Women in Malta: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Objective: This systematic review aimed to identify the barriers and facilitators affecting engagement with Malta’s National Breast Screening Programme (NBSP) among women aged 50–69, focusing on studies published over the past decade.

Methods: A comprehensive search of PsycINFO, PsychArticles, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar was conducted in June 2024, resulting in 48 records. Five full-text papers met the inclusion criteria, comprising English-language studies with quantitative, qualitative or mixed-method designs that examined breast screening engagement in Malta. Independent risk of bias and quality assessments were conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for cross-sectional studies.

Results: The review analysed data from 911 women, with a mean age range of 54.6–58.0 years. Barriers and facilitators to NBSP participation were categorised into three levels: psychological (knowledge gaps, fear and anxiety, health beliefs and illness perceptions), social (educational level, income and marital status) and healthcare-related (patient satisfaction and accessibility).

Conclusion: Targeted educational initiatives, improved accessibility and enhanced patient support could significantly boost screening uptake, leading to earlier breast cancer detection, reduced mortality rates and better health outcomes for women in Malta. These insights are not only valuable for refining breast screening programmes across Europe but can also inform similar initiatives globally, particularly in countries with comparable barriers and healthcare challenges. Adopting these strategies in diverse contexts may help improve women’s health outcomes worldwide.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, accounting for 23.8% of all new female cancer cases [1]. It is also the leading cause of cancer-related death among women, with one in six cancer-related deaths attributed to BC [1]. In Europe alone, the estimated incidence in 2022 was 604,900 cases [2]; this disproportionately affects women aged 50–64, who account for ~33% of BC cases, due to increased incidence rates associated with age-related cumulative genetic mutations and hormonal changes associated with menopause [3–6]. Early detection of BC has markedly reduced mortality in this age group [7, 8]. However, despite the benefits of early detection, the implementation of population-based mammography screening varies widely across Europe and is influenced by national policies, healthcare organisation and available resources [9].

Beyond its epidemiological significance, BC has a profound influence on the lives of women, affecting them physically, psychologically and socially. Those undergoing treatment often experience persistent pain [10, 11] and long-term side effects including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction and concerns about body image [12], adversely affecting their physical health and functionality. Additionally, increased levels of depression, anxiety and stress are commonly reported [13], and fear of cancer recurrence persists even after successful treatment [14]. Socially, BC survivors frequently report a lower quality of life due to high levels of social isolation and lack of support [15, 16]. Given this broad impact, promoting active engagement with breast screening programmes is crucial for the physical and mental well-being of patients.

In Malta, the Global Cancer Observatory reported 386 new BC cases and 81 BC-associated deaths in 2022, with age-standardised incidence and mortality rates of 86.3 and 15.1 per 100,000 women, respectively [17]. These rates are higher than the age-standardised rates of 70.7 and 14.5 per 100,000 women in Europe for incidence and mortality, respectively, as reported by The European BC Coalition [2] indicating a higher burden of BC in Malta. The Maltese Government introduced the National Breast Screening Programme (NBSP) in 2009 to enhance early BC detection and improve outcomes by providing free breast screening every 3 years to asymptomatic women aged 50–69 [18]. While recent data [19] revealed a promising 77.8% breast screening uptake rate, placing Malta among the top European Union countries in breast screening uptake, the persistently higher incidence and mortality rate compared with the World Health Organisation (WHO) Europe region average suggests that significant barriers to breast screening uptake remain that should be determined and addressed.

Despite the progress made by the Maltese NBSP, the discrepancy between breast screening rates, and the higher than average incidence and mortality rates suggests a complex interplay of factors influencing women’s decisions regarding breast screening. Understanding these factors is important for optimising the effectiveness of the NBSP and reducing the burden of BC in Malta. It has been suggested that these factors exist at multiple levels, including individual, interpersonal and healthcare system levels. At an individual level, factors such as lack of knowledge about breast screening frequency, perceived barriers (e.g., fear), low self-efficacy (e.g., doubting one’s own ability to navigate the healthcare system), fewer cues to act (e.g., recommendation from a healthcare professional) and socio-demographic factors (e.g., lower family income) may negatively impact breast screening uptake as part of the Maltese NBSP [20–23]. Additionally, effective communication and supportive care from radiographers have been identified as relational facilitators influencing patient satisfaction [24], which may increase the likelihood of women attending future breast screenings. At the healthcare system level, barriers commonly reported include the availability and accessibility of breast screening services, childcare responsibilities and the need for work leave [25, 26].

Given these complex challenges, conducting a systematic review investigating the barriers and facilitators of breast screening uptake in Malta is essential to (i) identify and understand the specific factors hindering breast screening uptake; (ii) highlight factors that have successfully increased breast screening uptake and could be leveraged or expanded; (iii) provide evidence-based recommendations to policymakers and healthcare providers to enhance the effectiveness of the Maltese NBSP and (iv) contribute to the broader European context by offering insights that may be applicable to other countries seeking to promote breast screening uptake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review Methodology

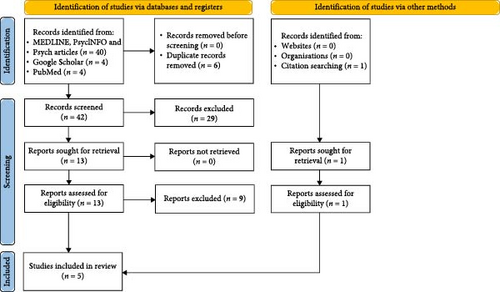

The present systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify studies relevant to barriers and facilitators to engagement with the breast screening programme in Malta. The protocol for the systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (Registration ID: CRD42024580313) to ensure transparency and adherence to predefined methodologies.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles that met the following criteria were included in the present systematic review: (i) published in a peer-reviewed journal, ensuring the studies have undergone a rigorous evaluation process to maintain scientific quality; (ii) included a sample of women aged 50–69 eligible for breast screening as part of the Maltese NBSP, as this age group is the target population for the programme; (iii) focused on breast screening behaviour or participation among women in Malta, aligning with the present systematic review’s objective to investigate factors influencing engagement with the Maltese NBSP; (iv) written in English or with an available English translation, to ensure accessibility and consistency in the presentation of the reported data; (v) published between 2011 and 2024, capturing the most recent studies reflecting current practices, policies and societal attitudes in Malta; (vi) original research articles with full-text availability, ensuring that the studies provided adequate study information and transparency and (vii) study designs being quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods, allowing for a broad range of perspectives and methods to be included in the present review to enhance the richness and applicability of the findings.

Studies were excluded if (i) they were not published in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) they did not include participants within the specified age range (50–69); (iii) they were not focused on breast screening behaviour/participation among women in the NBSP in Malta; (iv) they were nonoriginal research articles including book excerpts, reviews, editorials and postgraduate theses; (v) they were not published in the aforementioned specified timeframe (2011–2024); (vi) there was lack of full-text availability and (vii) they did not include the aforementioned study designs.

2.3. Search Strategy

Articles were identified via searches of the following databases: PsycINFO, PsychArticles, MEDLINE and Google Scholar in June 2024. Reference lists of relevant articles were also investigated. Search terms were generated by examining the terminology used in a previous review examining breast screening (e.g., [27]). Search terms included ‘breast cancer screening’ OR ‘mammogra ∗’ OR ‘breast imag ∗’ OR ‘breast exam ∗’ OR ‘breast check-up’ OR ‘cancer screening uptake’ OR ‘cancer examination uptake’ OR ‘screening behav ∗’ OR ‘screening participation’ AND ‘Malta’ OR ‘Maltese wom?n’ OR ‘Maltese adult ∗’ OR ‘Maltese female ∗’ AND ‘factor ∗’ OR ‘uptake’ OR ‘influence ∗’ OR ‘reason ∗’ OR ‘determinant ∗’ OR ‘barrier ∗’ OR ‘obstacle ∗’ OR ‘challeng ∗’ OR ‘constraint ∗’ OR ‘facilitat ∗’ OR ‘enabl ∗’ OR ‘adoption’ OR ‘acceptance’ OR ‘engagement’ OR ‘utili?ation’ OR ‘non-acceptance’ OR ‘non-engagement’ OR ‘non-attendance’ OR ‘avoidance’ OR ‘rejection’. Proximity operators, such as NEAR/3 and ADJ/2, were used to refine the search.

2.4. Search Results

The initial search yielded 48 records. After removing six duplicates, 42 records were screened, and 29 were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of the 13 full-text articles assessed, exclusions were made for the following reasons: PhD thesis (n = 2), book excerpt (n = 1), psychometric scale development (n = 1), breast compression techniques (n = 1), qualitative study focused on interviews with radiologists and radiographers from multiple countries, including Malta (n = 1), audit of the Maltese NBSP (n = 1) and non-peer-reviewed articles (n = 2). Journal titles were cross-checked with the Directory of Open Access Journals and the Committee on Publication Ethics; articles from journals on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme watchlist were excluded. One additional record was found through citation searches (Google Scholar). The present systematic review included a total of five full-text papers (Figure 1, PRISMA flow diagram; Table 1, study characteristics).

| Study | Design | Participants (n) | Mean ± SD | Demographics relevant to screening (%) | Measures | Statistical tests | First-time mammogram | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Marmara, Curtis, and Marmara [24] | Mixed: cross-sectional survey and thematic analysis | 380 | N/R | N/R | Satisfaction questionnaire (modified by Marmara, Curtis, and Marmara [24]) | Chi-square, descriptive statistics | N/R | Satisfaction with NBSP |

| (B) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [20] | Cross-sectional survey | 404 | 54.62 ± 2.80 | Primarily married, 86.9; housewives, 77; secondary education, 75.7 and below-average income, 60.3 | CHBMS-MS, IPQ-R, knowledge, socio-demographics and health status | Chi-square, logistic regression and descriptive statistics | Yes (first invitation) | Health beliefs and illness perceptions |

| (C) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [21] | Cross-sectional survey | 404 | 54.62 ± 2.80 | Same as study B | CHBMS-MS, IPQ-R, knowledge, socio-demographics, health status | Chi-square, t-test (unpaired)/Mann–Whitney | N/A adherence | Adherence to 3-year screening interval |

| (D) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [22] | Cross-sectional survey | 404 | 54.62 ± 2.80 | Same as study B | CHBMS-MS, IPQ-R, knowledge, socio-demographics, health status | Chi-square, t-test (unpaired)/Mann–Whitney, logistic regression | N/A lifetime use | Lifetime mammography use |

| (E) Gauci, Couto, and Mizzi [23] | Cross-sectional survey | 127 | 58 ± N/R (calculated) | Secondary education, 63; retired, 19; housewife, 19 and employed, 13 (calculated) | Self-designed questionnaire on breast density knowledge and awareness | Friedman test, Kruskal–Wallis test | N/R | Knowledge and awareness of breast density |

- Note: Calculated, calculated by the present authors using study data.

- Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; CHBMS-MS, Champion Health Belief Model Scale–Maltese; GP, general practitioner; IPQ-R, illness perception questionnaire-revised; N/A, not applicable; N/R, not reported; NBSP, National Breast Screening Programme.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction followed a modified Cochrane Collaboration template [28]. The corresponding author (Daniel Gaffiero) extracted data from two studies, while the second author (Brian Fenech) extracted data from the remaining three. Both authors then reviewed the data to ensure consistency across all studies. Extracted data included study aims, methods, participant demographics, inclusion/exclusion criteria, withdrawals, subgroup information, sample sizes, outcomes related to barriers and facilitators, statistical data, and key conclusions.

2.6. Quality Assessment of Studies A–E

In this review, the quality of included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies [29]. Authors Brian Fenech and Daniel Gaffiero independently evaluated each study, awarding 2, 1 and 0 points for fully met, partially met and unmet criteria, respectively, resulting in a total score range of 0–16. Studies were classified into three quality levels based on their total score: low (score range, 0–8), moderate (score range, 9–12), and high (score range, 13–16). To assess the risk of bias, each study’s total score was converted into a percentage, with the following risk classifications; high risk, ≤49%; moderate risk, 50%–69%; and low risk, >70%. A detailed breakdown of the quality assessment is provided in Table 2.

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Total | Quality level | Risk of bias, % (risk category) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Marmara, Curtis, and Marmara [24] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 11 | Moderate | 69 (moderate) |

| (B) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [20] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 | High | 100 (low) |

| (C) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [21] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 15 | High | 94 (low) |

| (D) Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [22] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 15 | High | 94 (low) |

| (E) Gauci, Couto, and Mizzi [23] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | Moderate | 81 (low) |

- Note: Quality level range: (i) low (0–8); (ii) moderate (9–12); (iii) high (13–16). Risk of bias range: (i) high, ≤49%; (ii) moderate, 50%–69%; (iii) low, >70%. For Q1–Q8, please refer to the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies [29].

- Abbreviation: Q, question.

Points were deducted for methodological and analytical shortcomings in the studies. Studies A and E used unvalidated methods for measuring exposure, with study A lacking information on the validation of its modified questionnaire and study E using an unvalidated questionnaire. All studies except study B inadequately addressed confounding factors, with studies A, C, D and E failing to employ rigorous multivariate analysis, weakening their findings. Study E also misclassified the non-parametric tests used as parametric. After quality assessments, authors resolved six discrepancies with 100% agreement. Studies B, C and D were rated as being high quality, while studies A and E were rated as being moderate. Although studies A and E provide valuable insights, their methodological limitations warrant cautious interpretation.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information of Participants in the Included Studies

The current review included five studies with a total of 911 women (mean age range, 54.6–58 years; studies B, C and D used the same participant cohort). It should be noted that although the same participant cohort was used across studies B, C and D, each study addressed different research questions, which led to the presentation of distinct aspects of the barriers and facilitators influencing engagement in the NBSP. While the cohort remained the same, the studies provided complementary and nuanced insights, with each study contributing new information relevant to the present systematic review (Table 1 for differing outcome measures). The inclusion of these studies was based on their ability to present unique perspectives or findings within the context of the overall research question. All studies were from Malta, with study B also including participants from Gozo. Studies A and B specifically recruited women in Malta, while study E did not specify ethnicity. The most common occupations included (i) housewives (77%) and (ii) employed but not in healthcare (24.4%). In study B, most women were married (86.9%), had a below-average income (<16,114€), owned a car (83.7%) but could not drive (56.2%), had a family physician (93.3%), were generally healthy (54.2%) and visited their physician only in emergencies (88.6%).

3.2. Study Designs Employed by the Authors of the Included Studies

Four studies used a cross-sectional questionnaire design, while study A employed a mixed-methods approach, combining cross-sectional questionnaires with thematic analysis, a form of qualitative analysis. Study A collected retrospective data via telephone from women who had participated in the Maltese NBSP, presenting statistical data under five themes (accessibility, efficiency, perception, supportive care and acceptability) without detailing the analytical approach or epistemological stance.

Studies B, C and D also used retrospective data via a telephone questionnaire. Study B categorised women as ‘attendees’ (n = 243) and ‘non-attendees’ (n = 161) based on their response to NBSP invitations. Study C focused on women who had received their first screening invitation, distinguishing between those screened within (‘adherent’, n = 324) or beyond (’non-adherent’, n = 80) the 3-year interval between invitations. Study D compared women who had previously attended a mammogram as part of the NBSP (‘lifetime attendees’, n = 348) with women who had not (‘non-lifetime attendees’, n = 56). Study E gathered data through intermediaries distributing the survey focusing on women attending a mammogram as part of the NBSP (n = 127).

3.3. Study Aims of the Included Studies

Study A aimed to evaluate women’s satisfaction with the NBSP during its prevalent call. Study B investigated the knowledge, health beliefs and illness perceptions about BC and screening in women in Malta, identified reasons for non-attendance of their screening appointment as part of the NBSP, and determined the socio-demographic, health status and other predictors associated with the uptake of the first invitation to breast screening. Study C explored the predictors for women in Malta screened within or exceeding the recommended 3-year frequency in organised (i.e., NBSP) or private screening in Malta. Study D sought to understand the determinants of attendance for mammography screening and examine the predictors of lifetime mammography use and non-use. Finally, study E aimed to assess knowledge and awareness of breast density among women in Malta attending a mammogram as part of the NBSP.

3.4. Barriers and Facilitators Affecting Uptake of NBSP

Barriers and facilitators influencing engagement with the NBSP were analysed across three primary levels (see Table 3 for an overview). At the psychological level, factors included knowledge, fear and anxiety, health beliefs and illness perceptions. The social level encompassed the influence of educational level, occupation, income and marital status. Lastly, factors at the healthcare level encompassed the infrastructure and services of the healthcare system, including accessibility, quality of care and effective communication with healthcare providers. These categories offer a structured framework for comprehensively examining and addressing the barriers and facilitators affecting engagement with the Maltese NBSP.

| Level | Sublevel | Barriers and facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological | Knowledge | Uncertainty about breast screening frequency, misconceptions about BC risk factors |

| Fear and anxiety | Fear of screening results, pain, unknown procedure, radiation and embarrassment | |

| Health beliefs |

|

|

| Illness perceptions | Emotional state, negative mental attitude, personality traits, anxiety about BC and belief that BC is hereditary | |

| Social | Educational level | Lower education associated with a higher refusal rate and reduced knowledge about breast density |

| Income | Lower income associated with lower screening attendance | |

| Marital status | Widowers less likely to attend mammography | |

| Healthcare | Patient satisfaction | Discomfort during mammogram, sex of radiographer (male), high satisfaction with care standards (pleasant environment, cleanliness, staff professionalism) |

| Accessibility | Transport issues, parking, not receiving invitation, being ill or on vacation | |

- Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; GP, general practitioner.

4. Psychological Level

4.1. Knowledge

The studies showed marked variability in knowledge about BC and screening. Study B revealed uncertainty about screening frequency, with 46.3% of women stating mammograms are annual and 43.3% stating mammograms take place every 2–3 years. Additionally, 38.7% and 47.5% of women mistakenly considered BC was caused by a ‘germ or virus’ or ‘accidents or injuries’, respectively. Study D linked knowledge of mammography frequency to lifetime screening participation, while study E highlighted limited awareness of the role of breast density in BC risk. These findings suggest that inconsistent knowledge and misconceptions about BC and screening frequency could affect both initial and ongoing participation in the NBSP.

4.2. Fear and Anxiety

Fear and anxiety about BC are prevalent among women in Malta. Study A found higher anxiety in older women (63.1% of women aged 59–61 vs. 50.2% of women aged 56–58), primarily due to fears about results and their impact. Study B reported widespread anxiety, with numerous participants concerned about the severe life consequences of BC and its influence on the progression of the disease. In that study, 41% of ‘non-attendees’ cited fear as a major reason for not participating, including fear about results (25%), pain (10%), unknown procedures (6.2%), radiation (3.7%) and embarrassment (8.1%). These findings indicate that fear and anxiety are marked barriers to NBSP uptake, especially regarding screening outcomes and procedures.

4.3. Health Beliefs

Three studies (B, C and D) assessed constructs of the Health Belief Model (HBM) influencing breast screening attendance. Perceived benefits were linked to higher first and lifetime screening attendance (studies B and D), while ‘non-attendees’ perceived fewer benefits, including reduced belief in early detection through screening (study B). Perceived barriers were the strongest HBM predictor of non-attendance (studies B, C and D). Barriers included fear of male mammographers, results, unknown procedures and mammography discomfort. The logistic regression in study D confirmed perceived barriers as the strongest predictor of non-attendance. Cues to action were important across most of the included studies (B, C, D and E). Attendance increased with healthcare provider advice or having a relative/friend diagnosed with BC, while advice from friends and family was less impactful. Media coverage, text/letter reminders and educational talks also influenced attendance. Study E highlighted a high demand for more information about breast density, with 90.6% of women preferring healthcare professionals as the information source. Self-efficacy was associated with screening attendance (studies B and D), indicating that confidence in managing screening logistics enhances participation in the Maltese NBSP.

4.4. Illness Perceptions

The findings pertaining to illness perceptions were generally mixed. Study B reported that ‘attendees’ agreed that BC could be hereditary and linked to behaviour, while ‘non-attendees’ were more undecided about the impact of emotional state and personality on BC. ‘Attendees’ were also more likely to believe that a patient with BC experiences cycles of getting better and worse, and they often acknowledged the major life consequences, serious economic and financial impact and the life-changing nature of BC. By contrast, study C found that while no specific constructs were significant, several individual factors were associated with adherence or non-adherence to screening. These factors included negative mental attitude, family problems and worries, emotional state (feeling down, anxious, empty or lonely), personality traits and anxiety about BC. Study D reported several emotional representations associated with non-lifetime attendance, such as emotional state, belief that BC was hereditary, thinking that a ‘germ or virus’ is a risk factor, recognising the major consequences of BC, and experiencing anxiety and fear. These findings indicate that illness perceptions, including beliefs about the causes, timeline and consequences of BC, as well as emotional responses, play a role in influencing engagement with the NBSP.

4.5. Social Level

The impact of social and demographic variables on breast screening attendance varied across studies. Study A observed higher refusal rates among women with primary (71.6%) and secondary (70.4%) education level compared with those among women with tertiary education (52.3%). Similarly, study E found that knowledge of breast density was influenced by educational attainment, with the least and most knowledgeable participants at primary and tertiary education levels, respectively. Study E also noted that healthcare workers were the most knowledgeable about breast density and BC risks, while housewives were the least knowledgeable. Study B identified no significant associations between demographic variables and first screening uptake, except for family income; those with lower income were less likely to attend breast screening. This finding was corroborated by study D which also noted the influence of marital status on mammogram attendance, with widowers being the least likely to participate. These findings suggest that educational level, occupation, income and marital status all play notable roles in influencing breast screening participation. Addressing disparities in knowledge and access among different social and demographic groups could enhance the overall effectiveness and reach of the Maltese NBSP.

4.6. Healthcare Level

Patient satisfaction emerged as a crucial factor influencing attendance at the NBSP. Study A reported that 31.3% and 68.7% of participants rated their screening experience as ‘good’ and ‘excellent’, respectively. Satisfaction with screening appointments was also high, with 95.5% and 99.2% of participants ‘very satisfied with screening appointments’ and ‘very satisfied with care standards’. Key factors influencing patient satisfaction included a pleasant environment, cleanliness and staff professionalism. However, only 68.9% expressed overall satisfaction with the entire programme. Regarding radiographer interaction, 99.7% of participants reported ‘feeling at ease’, and 98.4% rated the care as ‘excellent’. Nonetheless, 68.9% of women indicated they would decline screening if the radiographer was male.

Accessibility issues were highlighted as barriers in studies A, B and D. Study A reported that 29.74% of participants experienced access issues, negatively impacting satisfaction with the NBSP. Difficulty with parking was also noted as a reason for lower satisfaction levels. Study D found that lack of a driving licence was associated with a decreased likelihood of attending a mammogram. Study B revealed that 13.7% of women reported never receiving an invitation, while 8.7% reported being busy, having transport issues and being ill or on vacation as reasons for non-attendance.

Lastly, discomfort experienced during mammograms was shown to reduce satisfaction and increase doubts about repeat mammograms (study A), indicating that improving the comfort of the procedure could enhance patient satisfaction and encourage ongoing participation in the NBSP.

5. Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to investigate the barriers and facilitators to engagement with the Maltese NBSP among women aged 50–69. The persistently higher BC incidence and mortality rates in Malta, compared with the WHO Europe region average [20], highlight the need for targeted research to identify factors influencing screening behaviour. While a systematic review alone cannot directly address these issues, it is an essential step in understanding the underlying barriers and facilitators, which can inform the development of interventions aimed at improving screening participation and ultimately reducing the burden of BC in Malta.

The current review has identified a complex, multifaceted interplay of factors influencing screening uptake among women in Malta. Knowledge gaps and misconceptions about BC and screening [20] emerged as significant psychological barriers. The limited awareness of breast density and BC risk further compounds this issue [23]. These findings resonate with previous research in other countries [30, 31], emphasising the urgent need for tailored educational initiatives, such as culturally sensitive targeted campaigns and improved patient education materials to dispel misinformation and misconceptions about BC. This is particularly important since awareness and knowledge are critical in improving the chances of early detection of BC and enhancing quality of life [32]. Additionally, the pervasive fear and anxiety related to screening results, pain, the unknown procedure and radiation [20, 22], further highlight the necessity for interventions that address both cognitive and emotional barriers, echoing global concerns [33, 34]. While pre-screening counselling and patient navigators may prove beneficial, evidence suggests that specialised genetic counselling can markedly reduce anxiety and improve risk perception in women with family history of BC [35]. Integrating genetic counselling into MBSP for high-risk individuals could thus offer an avenue for mitigating psychological barriers, potentially improving screening uptake and adherence in this vulnerable population [36].

Consistent with the HBM [37], perceived barriers (e.g., fear, distrust and discomfort) were found to be the most influential factors negatively impacting screening adherence, while perceived benefits (e.g., detecting lumps early) and cues to action (e.g., general practitioner [GP] advice and reminders) facilitated adherence [20–22]. These findings indicate the importance of addressing perceived barriers and providing clear cues to action in promoting screening uptake, aligning with previous research [38–40]. The significant influence of cues to action, particularly GP recommendations, emphasises the potential of low cost, personalised interventions [21]. The positive impact of pre-screening reminders and primary care endorsement on screening participation has been well-documented [41]. A systematic implementation of personalised GP letters and reminders, tailored to address individual needs and health literacy levels, could significantly enhance screening uptake in Malta. Furthermore, leveraging mobile technologies, such as text message reminders or app notifications, could further enhance the effectiveness of reminders, particularly in reaching and engaging specific demographic groups. Research has shown that text messages incorporating GP endorsements notably improved cervical screening uptake [42]. Such digital interventions could thus prove invaluable in the context of breast screening in Malta.

Illness perceptions also emerged as a significant psychological factor influencing screening behaviour. Marmara, Marmara, and Hubbard [20–22] observed differences between ‘attendees’ and ‘non-attendees’ in their perceptions of the heritability of BC, behavioural factors and life consequences. Various factors, including negative mental attitudes, family problems, emotional state and anxiety about BC, were associated with screening adherence. These findings align with the common-sense model of self-regulation [43], which posits that individuals’ perceptions of their illness markedly influence their health behaviours. The necessity for interventions that not only provide accurate information about BC but also address the emotional aspects, such as anxiety and fear related to screening, is thus evident [44].

The interplay between psychological factors and broader socio-economic contexts further underscores the complexity of screening behaviour. Lower-than-average family income and educational attainment of secondary education or below were associated with decreased screening attendance [20, 22, 23], echoing international research highlighting socio-economic disparities in cancer screening uptake [45–47]. Addressing these disparities necessitates targeted interventions that tackle the specific barriers faced by lower income and less-educated groups. However, a systematic review [48] indicates that addressing socio-economic inequalities in cancer screening is challenging. While some interventions, particularly those integrated into existing programmes, showed promise, many failed to markedly reduce disparities. To elucidate further, while sending screening notifications via mail and text message reminders appeared to have a greater effect on encouraging participation among disadvantaged populations, the overall improvements were modest (range, 0.8%–3.6%). Interventions that failed to consider the unique barriers faced by these groups, such as low health literacy and the cognitive load of understanding complex information, often saw little to no impact, or even negative outcomes. The complex nature of health inequalities in cancer screening, encompassing individual and broader systemic and policy-level factors, necessitates interventions that empower women to engage with healthcare services [49].

Within the Maltese healthcare system, patient satisfaction emerged as a pivotal factor influencing screening participation. While factors such as pleasant environment, cleanliness and professional staff conduct contributed to higher satisfaction, discomfort during mammograms and the sex of the radiographer were notable deterrents. Improving the comfort of the procedure such as using breast cushions or tailored compression based on individual pain tolerance [50] and ensuring sex sensitivity in service provision could significantly enhance patient satisfaction and foster greater long-term participation in breast screening. The potential of mobile mammography units (MMUs) in improving accessibility and reaching underserved communities aligns with prior research demonstrating their success in increasing access and detecting early-stage cancer [51].

5.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present systematic review has certain limitations. Most studies focus on women aged 54.6–58.0, which does not fully represent the broader Maltese target age range of 50–69. Additionally, many studies are by the same lead author, Marmara, which may introduce bias and limit perspective diversity. It should also be noted that although studies B, C and D each used the same participant cohort, each study included different outcome measures which provided nuanced insights into barriers and facilitators influencing engagement in the NBSP. To expand, Study B focused on health beliefs and illness perceptions, study C screening adherence and Study D lifetime mammography use. Consequently, the total cohort (n = 911) included in the current systematic review was based on the total sample sizes of studies A, B and E, only, to avoid duplication and reporting of incorrect sample size. While Marmara et al.’s qualitative research is valuable, more comprehensive analyses like interpretative phenomenological analysis are needed to better understand the experiences of Maltese women and the role of GPs in screening engagement. The heterogeneity in study designs and methodologies also hindered meta-analysis. Finally, the review may not fully capture access variability across socio-economic and geographical subgroups, as noted by the EU’s ‘Beating Cancer’ plan [52]. Future research should broaden the age range, address accessibility issues, incorporate longitudinal and qualitative approaches, and use consistent, high-quality methodologies to enhance the generalisability and impact of findings on breast screening programmes globally. Moreover, future research should focus on understanding barriers to accessing breast screening in Malta among those who do not attend. This would lead to more targeted and effective public health interventions which would increase uptake in this population and thus has the potential to reduce BC-associated mortality due to early diagnosis.

6. Conclusions

The present systematic review highlighted the complex factors affecting engagement with the Maltese NBSP among women aged 50–69. Key barriers include knowledge gaps, fear, anxiety, socio-economic disparities and healthcare system challenges, while facilitators include healthcare provider cues to action, increased accessibility and advanced education. Effective strategies to improve screening uptake include tailored education, pre-screening counselling, MMUs and sex-sensitive services. Addressing systemic issues like socio-economic disparities and improving screening satisfaction are also crucial. Future research should expand to better represent diverse socio-economic and geographic subgroups, ensuring a more effective and equitable breast screening programme in Malta and across Europe.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Brian Fenech and Daniel Gaffiero contributed equally to this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michaela E. Christodoulaki for proofreading the manuscript prior to submission.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.