Predictors of Food Vendors’ Hygienic Practices in the Kadjebi District of Ghana: Implications for Public Health and Safety

Abstract

Background: Foodborne illnesses, caused by pathogenic microorganisms, mycotoxins or chemical hazards, are a global public health issue. The increasing trend of eating out and declining hygiene in food preparation have escalated the risk of these diseases.

Objective: This study assessed the predictors of food hygiene practices among food vendors in the Kadjebi District of Ghana.

Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted using a structured questionnaire to gather data from randomly selected street food vendors. The analysis included binary and multivariate logistic regression tests at a 0.05 significance level. Ethical approval was obtained with an ID UHAS-REC A.4[26] 19-20.

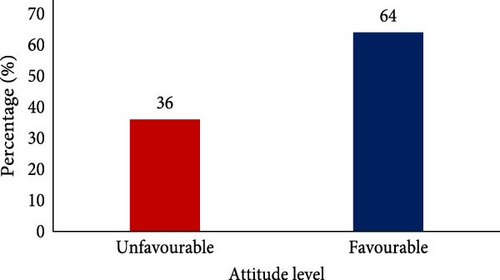

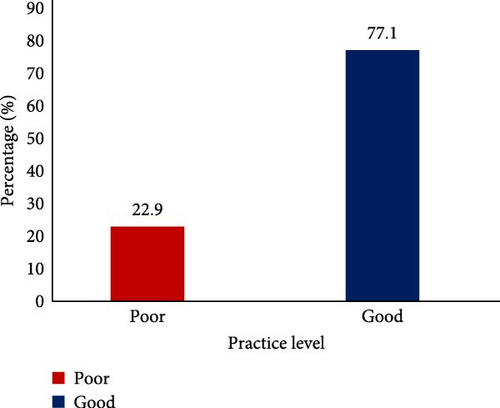

Results: The study found that 56% of vendors had adequate knowledge of food hygiene, with health workers being the primary source of information (49.7%). About 64% had a favourable attitude towards food hygiene, and 77.1% showed good hygienic practices. Significant factors influencing food hygiene practices were ethnicity (adjusted odds ratios [AOR] = 0.29, 95% confidence interval [Cl] [0.09–0.87], p = 0.027), received training (AOR = 0.34, 95% Cl [0.15–0.79], p = 0.012), water source for cooking (AOR = 2.48,95% Cl [2.13–7.93], p < 0.001) and attitude (AOR = 2.64, 95% Cl [1.19–5.20], p = 0.016).

Conclusion: This study identified key factors influencing food hygiene practices among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District. While most vendors demonstrated good hygiene practices, significant predictors included ethnicity, training, water sources and attitudes towards hygiene. Vendors from non-Akan ethnic groups exhibited lower adherence to hygiene practices, emphasizing the need for culturally and linguistically tailored health education. Continuous training and access to potable water are essential for maintaining food safety standards. Addressing these factors is critical to reducing foodborne illnesses and contributing to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 (Good Health and Well-being).

1. Introduction

Food is essential for human health and well-being, and access to safe, high-quality food is a fundamental human right that is vital for physical, social and mental health [1]. Street foods which are ready-to-eat meals sold by vendors in public spaces are a crucial part of urban and rural life globally, offering convenient and affordable nourishment [2, 3]. Vendors, who may be mobile or stationary, play a key role in the global food market but also significantly impact public health through their food handling practices [4]. In many developing countries, street food is a dietary staple, especially where economic opportunities are limited. However, concerns about safety and hygiene persist [5]. Improper food handling and poor hygiene practices by vendors can lead to foodborne illnesses, a concern heightened by the global trend towards eating out [5–7].

Although street foods offer socioeconomic benefits, such as providing affordable meals and employment, they often fail to meet hygiene standards, posing significant public health risks [8, 9]. Efforts by organizations like the Ghana Standards Authority and the Food and Drugs Board to regulate food safety face persistent challenges [10]. While vendors may have some hygiene knowledge, this does not always translate into practice, underscoring the need for continuous training and education [11]. The lack of regulation in street food vending contributes to widespread foodborne illnesses, with contamination stemming from raw materials, preparation areas, utensils and vendor hygiene [12, 13].

In Ghana, food safety remains a pressing issue, as foodborne illnesses affect 1 in 40 people annually, leading to significant economic losses [14]. Studies have shown high contamination rates in street foods due to poor vendor hygiene [15]. Food contamination in Ghana occurs at various points, with common causes including cooking in unsanitary environments, employing unhygienic cooking practices and using improper food storage methods [16]. The country reports over 626,000 cases of food poisoning annually, leading to ~298,100 hospitalizations (48% of reported cases) and over 90,000 deaths, contributing to 14% of all hospitalizations in the country [17]. Furthermore, foodborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery and viral hepatitis create significant challenges, placing a heavy burden on health authorities and straining the healthcare system [18].

Street foods are a major contributor to foodborne illnesses in developing countries, and in Ghana, where food safety lapses are common, diarrhoeal diseases rank as the eighth leading cause of death [19]. These outbreaks of diarrhoeal diseases and cholera highlight the urgent need to improve food safety practices, particularly since up to 70% of disease outbreaks in Ghana are linked to street food [11]. A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that foodborne diseases are often linked to poor food hygiene practices, with only 55.8% of food handlers demonstrating good hygiene standards [20]. Also, low level of knowledge was observed in 70.4% of food vendors, while 51% exhibited negative attitudes towards food safety and hygiene. Additionally, 52.3% demonstrated poor food hygiene practices [21]. This highlights the strong link between poor hygiene practices among vendors and the prevalence of foodborne illnesses in the country.

Although studies [11, 16, 17, 20, 21] have assessed food hygiene practices in Ghana, their findings do not reflect the specific situation in the Kadjebi District, likely due to contextual differences and other local factors. Moreover, Frempong et al. [22] assessed the intention of street food vendors in Kadjebi District, Ghana, to practice good food hygiene. However, the intention to adopt a behaviour does not always translate into actual practice. In 2023, cases of enteric fever in the Kadjebi District surged to 672, up from 370 in 2022 and 298 in 2021 [23]. While multiple factors may have contributed to this alarming increase, poor food hygiene among vendors is likely a major driver. Hence, this study is essential as it provides insights that are directly relevant to the current situation in relation to the knowledge, attitude and practice of food hygiene among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District.

By raising awareness among food vendors about the consequences of poor hygiene, this research aims to improve food safety practices in the Kadjebi District. The findings from this localized study can serve as a model for similar efforts worldwide, emphasizing the need for ongoing education and research to maintain high food safety standards. Ultimately, this study seeks to identify predictors of food hygiene practices among street food vendors in Kadjebi District, providing a basis for targeted health interventions. Also, this findings aims to contribute to the improvement of food safety practices in the district and the country at large and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 (Good Health and Well-being) [24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study adopted a cross-sectional design, using quantitative methods to collect data on respondents’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to food hygiene, as well as the factors influencing these practices. This design was chosen for its suitability in capturing a snapshot of the population at a specific point in time, allowing for efficient data collection in terms of time and resources. This study adopted the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines in drafting this paper [25]. Additionally, the methodology section of this study was adapted from a previous study [22]. The study was approved by the ethics committee from the University of Health and Allied Sciences with the ID UHAS-REC A.4[26] 19-20.

2.2. Description of the Study Site

The Kadjebi District is one of the 261 Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) in Ghana and is part of the 18 municipalities and districts within the Volta Region. Established by the Legislative Instrument (L.I.) 1465 in 1989, the district was carved out of the Jasikan-Buem Local Council. It covers a total land area of 689.91 km2 and is located in the lower belt of the Volta Region.

The district is bordered to the north by Nkwanta South Municipal, to the south by Jasikan District, to the southwest by Biakoye District and the northwest by Krachi East Municipal. It also shares an extensive eastern border with the Republic of Togo. According to the 2021 Population and Housing Census, the district has a population of 73,959, comprising 37,902 males and 36,057 females [26]. The Kadjebi District hosts four major markets, with 760 registered food vendors under the Environmental Health Unit of the District Assembly. Of these, 258 vendors operate in the Kadjebi Township, selling ready-to-eat foods to most of the population.

2.3. Study Population

This study was conducted among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District.

2.4. Selection Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

The study included male and female street vendors, aged 18 and above, who exclusively sold cooked, ready-to-eat foods along the district’s streets. Vendors were contacted via phone to confirm their availability, and those who consented were surveyed in person.

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

Vendors who declined consent or were unavailable during the data collection period were excluded from the study.

2.5. Sample Size Determination

The minimum sample size for this study was calculated using the Yamane formula [27] which is expressed as , where n = the sample size to be estimated; N = the total population size (760 food vendors) obtained from the environmental Health Unit of the District Assembly; and e = margin of error (5% or 0.005) at a 95% confidence interval (CI).

After adjusting for an anticipated 5% nonresponse rate, as adopted in previous study [28]:

n = (262.07 × 0.05) + 262.07 = 13.1035 + 262.07 = 275.1735.

Thus, a total sample size of 275 street food vendors who met the inclusion criteria were selected for the study.

2.6. Sampling Technique

A comprehensive list of food vendors in the Kadjebi District was obtained from the Environmental Health Unit of the District Assembly, containing details such as the vendors’ sex, age, location, contact information and types of food sold. This served as the sampling frame for the study.

To ensure accurate representation, vendors were contacted using the provided phone numbers to confirm their availability and vending locations. Their numbers were then written on slips of paper for random selection. A simple random sampling method was used, giving each vendor an equal chance of being chosen and reducing the risk of bias.

Vendors who consented to participate were included in the study. If a selected vendor could not be reached, their spot was filled by another randomly chosen vendor to meet the total number of food vendors estimated. Phone contacts and subsequent field visits were conducted to verify their status as active food vendors, ensuring reliable data collection. This sampling procedure was adopted from a previous study [22].

2.7. Reliability and Validity of Data Collection Instrument

Piloting was conducted with 10% of the sample size. This feedback improved the questionnaire’s structure, enabling necessary adjustments to ensure accurate measurement of all variables. Validity was established through expert review and alignment with empirical literature. A reliability coefficient of 0.7091 indicated an acceptable internal consistency [29].

A Cronbach’s pha of reliability test was used to test for internal reliability of the scale used to measure the knowledge, attitudes, practices and factors influencing food hygiene practices among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District, Ghana. Cronbach’s alpha indicates the degree to which the items that make up the scale correlate with each other in the group. Overall, a reliability coefficient of 0.7091 was obtained. This coefficient was compared to Cronbach’s coefficient value range from 0 to 1. It is suggested that a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.7 indicates consistency in the scale. Based on this, the scale or data collection instrument showed an internal consistency or reliability to assess knowledge, attitudes, practices and factors influencing hygiene practices among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District of Ghana. Calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient based on standardized values of items, STATA command alpha q1-q9, std item detail was computed. This command was used because items were not measured on the same scale. It also provides an unbiased estimate.

2.8. Data Collection Instrument and Procedure

Data for the study were gathered using a structured questionnaire designed to assess the knowledge, attitudes, practices and factors influencing food hygiene practices among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District. The questionnaire was administered through face-to-face interviews. Before the survey, respondents signed an informed consent form, ensuring voluntary participation.

- 1.

Demographic characteristics: This section included nine questions about the respondents’ personal information.

- 2.

Knowledge of food hygiene practices: This section also comprised nine questions, evaluating the respondents’ understanding of food hygiene.

- 3.

Attitude towards good food hygiene practices: With 10 questions, this section assessed vendors’ attitudes towards maintaining hygiene standards.

- 4.

Practice of food hygiene: This section included nine questions that evaluated the vendors’ actual food hygiene practices.

The questions related to knowledge, attitude and practices of food hygiene were adapted from similar studies to ensure relevance and consistency with established research methods [11, 16, 30, 31]. For instance, questions adopted and adapted from Ntow et al. and Frempong et al. [11, 22] share similar characteristics with the local context of the current study. As a result, the current only tweak the questions to elicit responses which would help this current study to answer the research questions.

The research team underwent a 3-day training session led by the principal investigator to familiarize themselves with the data collection tool. Following the training, a pretest was conducted with 15 street food vendors in the Hohoe Municipality, Volta Region, to assess the tool’s validity and reliability. This pretest helped identify potential issues with the questionnaire and allowed for necessary improvements before the actual data collection began in the Kadjebi District.

To minimize nonresponses, respondents were informed about the study’s purpose, and surveys were scheduled at convenient times. Trained data collectors ensured effective engagement and confidentiality. This assurance helped build trust and enhanced response rates.

3. Measures

3.1. Dependent Variables

The practice of food hygiene was treated as the dependent variable in this study. It was measured using nine items, with possible responses being ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’. For analysis, the ‘No’ and ‘Don’t know’ responses were combined into a single ‘No’ category. Each correct hygiene practice reported was awarded a score of 1 point, while incorrect hygiene practices reported were awarded a score of 0. This method of assessment was used in a previous study [28].

A composite variable was generated from the items measuring respondents’ practice. A mean score was calculated, with respondents scoring below the mean were considered to have poor practice, and those scoring above were deemed to have good practice of food hygiene. This method was adapted from a previous study [32].

3.2. Independent Variables

The independent variables were sociodemographic characteristics, sex categorized as male or female and age categorized as 18–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years and 50+. Marital status is classified as single, married or others. The level of education is grouped as no formal education, basic education, secondary education and tertiary education. Ethnic groups were categorized as Akan, Ewe and others. Religion was grouped as Christianity and Islam. How long have you been selling this food was grouped <10 years, 10–19 years and 20+ years. Undertaken training to sell this food was grouped as yes or no. Water source for cooking was categorized as borehole/well or pipe-borne. The types of foods were classified as rice and stew, fried yam, waakye, kenkey, beans and plantain and others.

For knowledge and attitude, composite scores were generated, and the average scores for each were computed as a guideline. For knowledge, eight items were used to generate the knowledge score. All ‘No’ and ‘Donot know’ responses were merged into ‘No’. For attitude, 10 questions were used to generate the attitude score. Similarly, all ‘No’ and ‘Donot know’ responses were merged into ‘No’. Each correct hygiene practice reported was awarded a score of 1 point, while incorrect hygiene practices reported were awarded a score of 0. This method of assessment was used in a previous study [28].

A composite variable was generated from the items measuring respondents’ knowledge and attitudes. A mean score was calculated, with respondents scoring below the mean considered to have inadequate knowledge, and those scoring above deemed to have adequate knowledge of food hygiene. Similarly, for attitude, respondents scoring below the mean were categorized as having an unfavourable attitude, while those scoring above were considered to have a favourable attitude towards food hygiene. This method of assessment was used in a previous study [32].

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were first entered into EpiData version 3.1 to ensure accurate data entry and minimize errors. After data entry, the dataset was exported to Stata version 16 for further cleaning and analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize variables, including demographic characteristics (age, gender and education level), knowledge of food hygiene, attitudes towards food safety and hygiene practices among the street food vendors. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, while means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables.

To evaluate the relationships between independent variables, demographic factors (such as age, gender and education), knowledge, attitude and outcome variable (food hygiene practice), a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted. Predictor variables with a p-value ≤ 0.05 from the initial bivariate analysis were considered significant and were subsequently included in a multivariable logistic regression model to control for potential confounding factors.

The strength of associations was expressed using adjusted odds ratios (AOR), along with their corresponding 95% CI. Statistical significance was determined at p-value ≤ 0.05.

The results were then presented in multiple formats, including text, figures and tables. Text was used to explain the key results, while figures (such as bar charts) visualized variables. Tables were used to display detailed statistical outputs, including odds ratios, CI and p-values.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Sociodemographic Findings

A total of 275 street food vendors in the Kadjebi District were recruited for the current study. A higher proportion 265 (96.4%) were females, and a relative majority 85 (30.9%) were between the ages of 30 and 39 with a mean age of 37 years. Also, about 188 (68.4%) were married, and 142 (51.6%) had a basic level of education. Akan was the least ethnic group representing 51 (18.6%), and people who belonged to other ethnic groups formed a relative majority of 123 (44.7%). Most of the respondents were Christians 156 (56.7%). Respondents who had sold food for less than 10 years constitute 193 (70.2%), and 92 (33.5%) had undertaken some training to sell food. Most of the respondents 226 (82.2%) got the water they use to prepare food from pipe-borne sources, and waakye was the most sold food 84 (30.5%) (Table 1).

| Variable | Frequency (percentage) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (3.6) |

| Female | 265 (96.4) |

| Age mean (standard deviation [SD]) | 37 (±11) |

| 18–30 | 83 (30.7) |

| 30–39 | 85 (30.9) |

| 40–49 | 54 (19.6) |

| 50+ | 53 (19.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 62 (22.5) |

| Married | 188 (68.4) |

| Others | 25 (9.1) |

| Level of education | |

| No formal education | 91 (33.1) |

| Basic education | 142 (51.6) |

| Secondary education | 42 (15.3) |

| Tertiary education | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnic group | |

| Akan | 51 (18.6) |

| Ewe | 101 (36.7) |

| Other | 123 (44.7) |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | 156 (56.7) |

| Islam | 119 (43.3) |

| How long have you been selling this food | |

| <10 years | 193 (70.2) |

| 10–19 years | 53 (19.3) |

| 20+ years | 29 (10.6) |

| Undertaken training to sell this food | |

| Yes | 92 (33.5) |

| No | 183 (66.5) |

| Water source | |

| Borehole/well | 49 (17.8) |

| Pipe borne | 226 (82.2) |

| Type of foods | |

| Rice and stew | 42 (15.3) |

| Fried yam | 26 (9.5) |

| Waakye | 84 (30.5) |

| Kenkey | 57 (20.7) |

| Beans and plantain | 27 (9.8) |

| Others | 39 (14.2) |

- Note: Waakye, beans and rice; Kenkey, cooked corn dough in maize husk.

4.2. Knowledge About Food Hygiene

From Table 2, more than half, 39 (78.0%), had heard of food hygiene before. Nearly 41 (82.0%) knew that washing hands before preparing food reduced the risk of food contamination, and 33 (66.0%) reported that proper cleaning of utensils before serving food decreases the risk of food contamination. Of the respondents, 33 (66.0%) asserted that food prepared a day before sale does not reduce the risk of contamination.

| Variable | Frequency (percentage) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Heard of food hygiene | |

| Yes | 189 (68.7) |

| No | 86 (31.3) |

| Main source of information | |

| School | 61 (32.3) |

| Media | 26 (13.8) |

| Health worker | 94 (49.7) |

| Other | 8 (4.2) |

| Washing hands before preparing food reduces the risk of food contamination | |

| Yes | 256 (93.1) |

| No | 19 (6.9) |

| Proper hand hygiene can prevent foodborne diseases | |

| Yes | 273 (99.3) |

| No | 0 (0.0) |

| Do not know | 2 (0.7) |

| Proper cleaning of utensils before use decreases the risk of food contamination | |

| Yes | 192 (69.8) |

| No | 83 (30.2) |

| Food prepared a day before sale reduces the risk of food contamination | |

| Yes | 122 (44.3) |

| No | 152 (55.3) |

| Do not know | 1 (0.4) |

| Washing utensils with detergent leaves them free of contamination | |

| Yes | 259 (94.2) |

| No | 11 (4.0) |

| Do not know | 5 (1.8) |

| All persons can get ill due to food poisoning | |

| Yes | 240 (87.3) |

| No | 20 (7.2) |

| Do not know | 15 (5.5) |

| Contaminated foods always have some change in taste | |

| Yes | 261 (94.9) |

| No | 14 (5.1) |

Additionally, a significant proportion, 48 (96.0%), knew that washing utensils with detergents leaves them free of contamination, and 45 (90.0%) said all persons can get ill due to food poisoning. Most of the respondents 46 (92.0%) knew that contaminated foods always have some change in taste. Overall, as shown in Figure 1, 28 (56%) of the respondents had adequate knowledge of food hygiene.

4.3. Food Vendors’ Sources of Information

Health workers were the primary source of information for 49.7% of food vendors. About 32.3% of them stated that schools were their sources of information. Media sources contributed to 13.8% of food vendors’ knowledge, while other sources accounted for 4.2% of their knowledge about food hygiene (Figure 2).

4.4. Food Vendor’s Attitude Towards Food Hygiene

The attitude of respondents towards food hygiene is presented in Table 3. A high proportion of the respondents 257 (93.5%) recognized that safe food handling is an important part of their job responsibilities. Again, 260 (94.5%) further reported that wearing caps and adequate clothing is an important practice to reduce the risk of food contamination. Most, 254 (92.4%), recognized that dirtied fingernails could contaminate food, and 148 (53.8%) asserted that learning more about food safety through training courses is important.

| Variable | Frequency (percentage) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Safe food handling is an important part of my job responsibilities | |

| Yes | 257 (93.5) |

| No | 0 (0.0) |

| Do not know | 18 (6.5) |

| Wearing caps and adequate clothing is an important practice to reduce the risk of food contamination | |

| Yes | 260 (94.5) |

| No | 7 (2.6) |

| Do not know | 8 (2.9) |

| Dirtied fingernails could contaminate food with foodborne pathogens | |

| Yes | 254 (92.4) |

| No | 5 (1.8) |

| Do not know | 16 (5.8) |

| Learning more about food safety through training courses is important to me | |

| Yes | 148 (53.8) |

| No | 59 (21.5) |

| Do not know | 68 (24.7) |

| Knives and cutting boards should be properly washed to prevent cross-contamination | |

| Yes | 260 (94.5) |

| No | 1 (0.4) |

| Do not know | 14 (5.1) |

| Food handlers who have abrasions or cuts on their hands should not touch foods without gloves | |

| Yes | 209 (76.0) |

| No | 56 (20.4) |

| Do not know | 10 (3.6) |

| Do you think you cannot prepare food and sell when suffering from a foodborne illness | |

| Yes | 240 (87.3) |

| No | 22 (8.0) |

| Do not know | 13 (4.7) |

| It is good to maintain a high degree of personal cleanliness while working | |

| Yes | 266 (96.7) |

| No | 1 (0.4) |

| Do not know | 8 (2.9) |

| Raw foods should be kept separately from cooked foods | |

| Yes | 214 (77.8) |

| No | 54 (19.7) |

| Do not know | 7 (2.5) |

| Health status of food vendors should be evaluated before they start selling to the public | |

| Yes | 265 (96.4) |

| No | 8 (2.9) |

| Do not know | 2 (0.7) |

Of the respondents, 260 (94.5%) stated that knives and cutting boards should be properly washed to prevent cross-contamination, and most of the respondents 209 (76.0%) also said food handlers who have abrasions or cuts should not touch food without gloves. Nevertheless, 22 (8.0%) thought they could not prepare food and sell it when suffering from a food-borne illness. The majority of the respondents 266 (96.7%) thought it is good to maintain a high degree of personal cleanliness while working, and 214 (77.8%) thought raw and cooked foods should be kept separately. Also, 265 (96.4%) of the respondents recognized that the health status of food vendors should be evaluated before they start selling food to the public. Overall, 176 (64%) of the food vendors had a favourable attitude towards food hygiene as shown in (Figure 3).

4.5. Practices of Food Hygiene Among Food Vendors

More than half of the respondents 268 (97.5%) did not put nail polish when handling food; however, 26 (9.5%) allowed their fingernails to grow long; 7 (2.5%) did not wash their hands with soap and water after visiting the toilet; the majority, 211 (76.7%), did not prepare their food a day before sales, and most, 265 (96.4%), properly cleaned food storage areas before storing cooked foods. About 67 (24.4%) wore gloves when handling food; most, 213 (77.5%), stored raw and cooked foods separately to reduce the risk of food contamination, and 116 (42.2%) wore aprons while selling food. Most of the respondents 205 (74.5%) also checked the expiry dates of processed foods before using them (Table 4). About 212 (77.1%) had good food hygiene practices, as indicated in Figure 4.

| Variable | Frequency (percentage) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Wear nail polish when handling food | |

| Yes | 7 (2.5) |

| No | 268 (97.5) |

| Allow fingernails to grow long | |

| Yes | 26 (9.5) |

| No | 249 (90.5) |

| Wash hands with water and soap after using the toilet | |

| Yes | 268 (97.5) |

| No | 7 (2.5) |

| Prepare meal a day before sale | |

| Yes | 64 (23.3) |

| No | 211 (76.7) |

| Properly clean the food storage area before storing cooked foods | |

| Yes | 265 (96.4) |

| No | 10 (3.6) |

| Wear gloves when you handle ready-to-eat food | |

| Yes | 67 (24.4) |

| No | 208 (75.6) |

| Store raw and cooked foods separately to reduce the risk of food contamination | |

| Yes | 213 (77.5) |

| No | 61 (22.1) |

| Do not know | 1 (0.4) |

| Wear an apron while working | |

| Yes | 116 (42.2) |

| No | 159 (57.8) |

| Check the expiry dates of processed foods | |

| Yes | 205 (74.5) |

| No | 70 (25.5) |

4.6. Predictors of Food Vendors’ Hygiene Practices

The predictors of food vendors’ hygienic practices are detailed in Table 5. In Model I, a chi-square test revealed that ethnicity (p = 0.046), training undertaken (p < 0.001), water source (p < 0.001), knowledge (p < 0.001) and attitude (p < 0.001) were significant predictors of vendors’ food hygiene practices. These variables were then included in a binary logistic regression (Model II) to assess the strength of their association with the dependent variable (hygiene practice). However, after adjusting for confounders in a multivariate analysis (Model III), ethnicity, training undertaken, water source and attitude emerged as significant predictors of hygiene practices among food vendors. Belonging to an ethnic group other than Akan was associated with significantly lower likelihoods of good hygiene practices, 71% less likely among the Ewes (AOR = 0.29 [CI: 0.09, 0.87], p = 0.027) and 69% less likely among other ethnic groups (AOR = 0.31 [CI: 0.10, 0.91], p = 0.033). Food vendors without any training in food sales were 66% less likely to maintain good food hygiene practices(AOR = 0.34 [CI: 0.15–0.79], p = 0.012). Additionally, those who sourced their water from pipe-borne sources were twice as likely to have good hygiene practices (AOR = 2.48 [CI: 1.19, 5.20], p = 0.016). Attitude also played a vital role, and respondents with a favourable attitude were three times more likely to have good hygiene practices (AOR = 2.64 [CI: 1.39, 5.02], p = 0.003).

| Variable | Hygiene practices | Model I | Model II | Model III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Poor = 63 (22.9%) n (%) |

Good = 212 (77.1%) n (%) |

Chi-square (χ2) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | — | — | 0.07 | — | — |

| Male | 0 (0) | 10 (4.7) | — | — | — |

| Female | 63 (100) | 202 (95.3) | — | — | — |

| Age | — | — | 0.127 | — | — |

| <30 | 13 (20.6) | 70 (33.0) | — | — | — |

| 30–39 | 24 (38.1) | 61 (28.8) | — | — | — |

| 40–49 | 16 (25.4) | 38 (17.9) | — | — | — |

| 50+ | 10 (15.9) | 43 (20.3) | — | — | — |

| Marital status | — | — | 0.99 | — | — |

| Single | 14 (22.2) | 48 (22.6) | — | — | — |

| Married | 43 (68.3) | 145 (68.4) | — | — | — |

| Others | 6 (9.5) | 19 (9.0) | — | — | — |

| Level of education | — | — | 0.07 | — | — |

| No formal education | 24 (38.1) | 67 (31.6) | — | — | — |

| Basic education | 35 (55.6) | 107 (50.5) | — | — | — |

| Secondary education | 4 (6.4) | 38 (17.9) | — | — | — |

| Ethnic group | — | — | 0.046a | — | — |

| Akan | 5 (7.9) | 46 (21.7) | — | Ref | Ref |

| Ewe | 27 (42.9) | 74 (34.9) | — | 0.30 (0.11–0.83), 0.020a | 0.29 (0.09–0.87), 0.027a |

| Other | 31 (49.2) | 92 (43.4) | — | 0.32 (0.12–0.88), 0.028a | 0.31 (0.10–0.91), 0.033a |

| Religion | — | — | 0.831 | — | — |

| Christianity | 35 (55.6) | 121 (57.1) | — | — | — |

| Islam | 28 (44.4) | 91 (42.9) | — | — | — |

| Duration of sale | — | — | 0.638 | — | — |

| <10 year | 44 (69.8) | 149 (70.3) | — | — | — |

| 10–19 years | 14 (22.2) | 39 (18.4) | — | — | — |

| 20+ years | 5 (7.9) | 24 (11.3) | — | — | — |

| Undertaken training to sell this food | — | — | <0.001a | — | — |

| Yes | 8 (12.7) | 84 (39.6) | — | Ref | Ref |

| No | 55 (87.3) | 128 (60.4) | — | 0.22 (0.10–0.49), <0.001a | 0.34 (0.15–0.79), 0.012a |

| Water source | — | — | <0.001a | — | — |

| Borehole/well | 23 (36.5) | 26 (12.3) | — | Ref | Ref |

| Pipe borne | 40 (63.5) | 186 (87.7) | — | 4.11 (2.13–7.93), <0.001a | 2.48 (1.19–5.20), 0.016a |

| Type of food | — | — | 0.084 | — | — |

| Rice and stew | 9 (14.3) | 33 (15.7) | — | — | — |

| Fried yam | 4 (6.35) | 22 (10.4) | — | — | — |

| Waakye | 19 (30.2) | 65 (30.7) | — | — | — |

| Kenkey | 21 (33.3) | 36 (17.0) | — | — | — |

| Beans and plantain | 5 (8.0) | 22 (10.4) | — | — | — |

| Others | 5 (8.0) | 34 (16.0) | — | — | — |

| Knowledge | — | — | <0.001a | — | — |

| Inadequate | 7 (11.1) | 114 (53.8) | — | Ref | — |

| Adequate | 56 (88.9) | 98 (46.2) | — | 1.10 (0.05–0.25), 0.10 | — |

| Attitude | — | — | <0.001a | — | — |

| Unfavourable | 38 (60.3) | 61 (28.8) | — | Ref | Ref |

| Favourable | 25 (39.7) | 151 (71.2) | — | 3.76 (2.09–6.76), <0.001a | 2.64 (1.39–5.02), 0.003a |

- Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio.

- aSignificant at p-value < 0.05.

5. Discussion

This cross-sectional study conducted in the Kadjebi District explored the predictors of food hygiene practices among street food vendors. The significance of good food safety practices in preventing foodborne diseases cannot be overstated. The study revealed that 77.1% of the respondents adhered to good food hygiene practices, a finding consistent with a similar study in Accra, Ghana, which reported 52% of vendors practising good hygiene [30]. However, this contrasts with a study in Nigeria, where only 36.5% of respondents exhibited adequate food hygiene practices [33]. The positive results in Kadjebi may be attributed to the respondents’ solid knowledge base and positive attitudes towards food safety. This is encouraging, as it suggests that most food sold in the district is hygienic, reducing the risks of foodborne illnesses, food poisoning and contamination. However, continued efforts are still needed to improve the adherence to hygienic practices among nonadherent vendors.

Hand hygiene, a crucial aspect of food safety, was well-practiced among respondents, with 97.5% indicating they washed their hands with soap and water after using the toilet. This finding aligns with a similar study in Accra, where 92% of vendors also reported handwashing with antibacterial soap [30].

Moreover, 77.5% of the vendors used separate containers for raw and cooked food, reducing the likelihood of cross-contamination, a finding consistent with a study in Ghana where 99.9% of food vendors adhered to this practice [34]. Additionally, only 23.3% of vendors prepared food a day in advance, implying most food was freshly cooked an approach that significantly reduces contamination risk. This contrasts with findings from [34], where 81.9% of vendors stored food overnight.

Ethnicity emerged as a predictor of food hygiene practices, with vendors from non-Akan ethnic groups demonstrating lower levels of food hygiene practice. This could be due to language differences and distinct culinary traditions influencing understanding and adherence to food safety guidelines. Regulations often disseminated in dominant languages like Akan or English may be harder to comprehend for some groups [35]. Also cultural norms in food-handling methods may also shape their food hygiene practices [36, 37]. This finding highlights the need for culturally sensitive and linguistically inclusive health education campaigns tailored to diverse ethnic groups to improve food hygiene and safety across different populations. Furthermore, the study found that prior training in food vending was significantly associated with better food hygiene practices, aligning with findings from Vietnam [31]. This suggests that untrained food vendors may unknowingly engage in unsafe practices, increasing the risk of food contamination and foodborne illnesses. Therefore, training programs on food hygiene must be expanded and reinforced by relevant authorities.

The source of water used by the vendors also had a significant relationship with food hygiene practices, consistent with findings from Hohoe Township, Ghana, where vendors predominantly relied on piped water [11]. This underscores the importance of accessible and affordable potable water, as it is a key resource in maintaining food hygiene during preparation and serving. This implies that a potable source of water is essential in practising good food hygiene as it is used for food preparation and serving. Access to portable water is a basic need and hence should be made available and accessible to everyone at an affordable cost.

Prüss-Ustün et al. [38] provide strong evidence that national water policies aimed at improving access to safe drinking water can significantly reduce waterborne diseases and enhance public health. Stakeholders should also reinforce global and national policies, including SDG 6, the UN Human Right to Water, the Dublin Statement (1992), Ghana’s National Water Policy (2007, revised 2024) and the Ghana Water Sector Strategic Development Plan (2012–2025) to achieve universal access to safe drinking water through sustainable management, equitable distribution and integrated resource planning [39, 40]. Proper alignment and implementation of these policies will promote best practices for safe good food practices among vendors.

This study revealed that having a favourable attitude significantly enhances food hygiene practices, with 64% of food vendors displaying a favourable attitude towards food hygiene. These findings contrast with studies conducted in Sierra Leone and Ghana, where 76% and 51% of food vendors, respectively, exhibited unfavourable attitudes towards food hygiene [21, 41]. The favourable attitudes observed in this study may be linked to the sources of information available to food vendors, as 49.7% cited health workers as their primary source of guidance. A similar pattern was seen in Ethiopia, where health workers or inspectors were the predominant source of information, and a favourable attitude was a strong predictor of better food hygiene practices [42]. This finding implies that health workers/inspectors should strengthen food inspections to ensure compliance with hygiene standards among food vendors. This regular inspection will help good food vendors consistently adhere to proper food safety protocols.

The study found that a favourable attitude among food vendors was closely linked to improved food hygiene practices. Similarly, research conducted in Northwest Ethiopia showed that vendors with positive attitudes were more likely to demonstrate good food hygiene practices [43, 44]. This reflection could be due to food vendors being more responsive to educational programs and training conducted within the district. However, these findings are in contrast with other studies in Ethiopia and Nigeria [45, 46].

Improved food hygiene practices reduces foodborne illnesses (e.g. cholera and typhoid), lowers mortality rates and eases the burden on healthcare systems and ultimately contribute to SDG 3. Foodborne illnesses pose significant public health threats, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where food hygiene practices are often inadequate [47]. Studies have demonstrated that proper food handling, safe water usage and improved sanitation are key factors in preventing foodborne illnesses. Food contaminated with pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella typhi accounts for millions of cases of diarrhoeal diseases globally each year [47]. A study [48] found that food hygiene interventions, such as handwashing with soap, safe food preparation and improved kitchen sanitation, can reduce diarrhoeal diseases by up to 47%. Furthermore, food hygiene education and access to clean water significantly lower the risk of cholera outbreaks [49].

The mortality associated with foodborne illnesses is largely preventable through improved hygiene measures. Cholera, for instance, can cause severe dehydration and death if left untreated, with mortality rates exceeding 50% in severe cases [50]. However, implementing food safety measures has been shown to lower fatality rates. A study [51] revealed that improved household and community hygiene interventions reduced cholera-related mortality by 60%. Similarly, evidence from Ghana suggests that enhancing food vendor hygiene and surveillance efforts can significantly mitigate typhoid outbreaks [52].

Foodborne illnesses contribute to substantial healthcare costs, including hospital admissions, treatment and lost productivity [53]. Appropriate interventions can lead to a 30% reduction in hospital admissions due to foodborne illnesses [54]. This not only alleviates pressure on healthcare infrastructure but also reduces healthcare expenditure for both governments and individuals.

6. Limitations of the Study

First, respondents’ awareness of being observed may have influenced their food hygiene practices, potentially leading to response bias. However, respondents were assured of anonymity and informed that their responses were being used strictly for research purposes. However, social desirability bias may persist. Second, the cross-sectional design limits the study’s ability to track changes in vendors’ knowledge, attitudes and practices over time, making it impossible to measure shifts in behaviour or improvements resulting from this study. Additionally, the study could not verify the food hygiene certification status of vendors since a list provided by the Environmental Health Department was used. Finally, the study only captured whether respondents had undergone training or not without assessing the content, frequency or quality of the training. This restricts our ability to determine the specific aspects of training that may influence food hygiene practices. Future research should explore these dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of training in enhancing food hygiene practices among food vendors. Also, economic constraints and cultural beliefs should be further explored. Nevertheless, this does not compromise the validity of the study’s findings.

7. Conclusion

This study identifies key predictors of food hygiene practices among street food vendors in the Kadjebi District, emphasizing the need for continuous education, infrastructure improvements and culturally sensitive health interventions to maintain food safety standards. Essentially, food hygiene practice was predicted by the ethnic group of respondents, whether or not respondents have undertaken some training, their knowledge level and their attitudes towards food hygiene practices. While health workers play a significant role, other stakeholders including policymakers, community leaders and food regulatory authorities are also crucial. Policymakers can implement regulations, community leaders can drive awareness, and food regulatory authorities can enforce compliance through inspections and training. By addressing these factors and engaging all stakeholders, public health efforts can enhance food vending practices, contributing to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being).

8. Implications for Practice

Enhancing the knowledge of food vendors in the Kadjebi District can foster more favourable attitudes towards food hygiene and promote the adoption of good hygiene practices. This goal can be achieved through continuous education within the district, aiming to increase knowledge and address cultural norms to drive behavioural changes among food vendors.

To further this effort, the Environmental Health Department can conduct intermittent workshops across various communities and remote areas. These workshops would enhance hygiene knowledge and emphasize the importance of maintaining good food hygiene practices.

Additionally, the department can organize empowerment programs to help food vendors overcome barriers to food hygiene practices. These programs can focus on developing self-efficacy and cultivating a strong positive attitude towards maintaining high standards of food hygiene rather than punitive measures. Regular follow-up assessments and continuous monitoring of food vendors are essential for sustaining these initiatives, ultimately enhancing food hygiene practices in the Kadjebi District.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Health and Allied Sciences Research Ethics Committee (UHAS-REC A.4 [26] 19-20) and permission from the Environmental Health Unit of Kadjebi District Assembly. Respondents received full information in their preferred language and provided informed consent voluntarily. No personally identifiable information was collected, with responses assigned unique codes instead of names. All data were securely stored in password-protected electronic files and kept in a restricted-access location. Access was limited to key research personnel, ensuring strict control over sensitive information. The study posed no risk, ensured confidentiality and adhered to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Consent

Participants received full information in their preferred language and provided informed consent voluntarily.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C.S.F. and D.M.O. conceptualized the study. C.S.F. supervised and provided valuable insights into the conceptualization of the study and the manuscript. P.A., D.M.O., B.A.S. and A.K.M.-A. developed the manuscripts. D.K.M. and D.M.O. analysed the data and presented results for the study. All authors approved the final manuscripts.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the staff of the Kadjebi District Assembly for their approval and support in facilitating our data collection for this study. We also appreciate the cooperation of our study respondent who rewere instrumental in the success of this research. Finally, we extend our sincere gratitude to the Ghana Health Service for granting us the opportunity to present our findings at the 3rd Social and Behaviour Change Evidence Summit.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.