Plasma Inflammatory Biomarkers Indicative of Aging and Overweight in Brazilian Women

Abstract

Immunosenescence is a process of immune system remodeling based on the natural aging process. Factors such as diet, physical exercise, mental health, and genetic/metabolic conditions can influence the development of age-related inflammation. In senescence, overweight and obesity are silent inflammatory conditions that predispose individuals to cardiovascular diseases and other comorbidities. This study aimed to evaluate the concentration of obesity-related plasma biomarkers (creatine kinase (CK), CXCL16, IL-33, leptin, and resistin) in clinically stable women of different ages and weights. A cross-sectional study was conducted in Minas Gerais State, Brazil, involving 54 women (aged 20–85 years), assisted by the Brazilian Public Health Service. Socioeconomic and anthropometric parameters were assessed, and plasma levels of CK, CXCL16, IL-33, leptin, and resistin were measured using immunological and biochemical assays. Out of the total study participants, 54 women (mean age 44.9 years) were overweight and presented high plasma levels of CK, CXCL16, IL-33, and leptin. Specifically, plasma CK levels were similar in adults, middle-aged, and elderly women, but there was an increase in its release associated with overweight in adults and elderly women. Plasma IL-33, CXCL16, and resistin were reduced in elderly clinically stable women but not leptin. However, when volunteers were grouped according to body mass index, CXCL16, IL-33, and leptin were elevated and associated with overweight. Together, plasma levels of CK, CXCL16, IL-33, and leptin were identified as promising indicators of immunosenescence, regardless of weight parameters. Moreover, CXCL16 levels evaluated as an isolated parameter were a stronger indicator of obesity, regardless of aging.

1. Introduction

Age-related immune system remodeling, known as immunosenescence, leads to a progressive reduction in cellular and humoral immune responses, making individuals more vulnerable as they near the end of their lives [1]. The hallmarks of immunosenescence include progressive changes in the phenotypes and functionality of T, natural killer, phagocytic-related, and B cells, resulting in a diminished or failed role in a low-grade inflammatory condition referred to as “inflamm-aging” [2, 3]. The progressive immune system alterations associated with aging have a direct impact on lifespan. However, lifestyle and dietary modifications can help prevent or delay the aging immune system remodeling, thereby contributing to a better quality of life during the natural process of senescence [4].

Overweight and obesity are multifactorial global epidemics influenced by clinical, genetic, emotional, social, and cultural factors. They are characterized by excessive caloric intake and physical inactivity [5, 6]. Excessive accumulation of adipose tissue, resulting in increased body weight, is associated with the release of bioactive mediators [7]. Inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNF, leptin, resistin, chemokines (CCL2, CXCL16), amyloid-A, and C-reactive protein can be upregulated in overweight conditions [8, 9, 10]. To predict obesity- and overweight-related diseases in adults and the elderly, the roles of potential biomarkers have been proposed. Recently, we demonstrated that CXCL16, an interferon-gamma-regulated chemokine and scavenger receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein [11, 12], was found to be overproduced in overweight adults and the elderly [13]. We have also identified other potential markers associated with aging and obesity, such as IL-33 [14, 15, 16], CCL2, CCL5, leptin, and resistin [17].

Studies investigating the decline in the age-related immune system and obesity-induced inflammation have led to the identification of prognostic targets applicable in clinical practice. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the plasma concentrations of CK, CXCL16, IL-33, leptin, and resistin in clinically stable and elderly women with normal weight and overweight conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This was a cross-sectional epidemiological study conducted with Brazilian female participants, recruited through data collection from the family health strategy units located at Teófilo Otoni, a Northeast city of Minas Gerais State, Brazil, from 2019 to 2020. Participants diagnosed with psychiatric disorders and clinical pathologies such as hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorders, metabolic syndrome, kidney or systemic diseases, as well as those on medication or steroid drugs, were excluded from the study; these conditions would not allow for a proper interpretation of the relationship between obesity-related diseases and immunological parameters in elderly individuals.

To ensure the clinically stable condition of all participants, complete blood counts, fasting blood glucose levels, total cholesterol and fractions, triglycerides, abnormal elements of the sediment, and parasitological examination of feces were performed once during clinical assessment.

This study included 54 clinically stable women (24 adults, 21 middle-aged, and 9 elderly), 30 overweight women (13 adults, 13 middle-aged, and 4 elderly), and 24 normal-weight women (11 adults, 8 middle-aged, and 5 elderly). The average age of the participants was 44.9 years.

2.2. Anthropometric Measurements

The weight and height of the participants were measured and used to calculate the body mass index (BMI), which is calculated as weight divided by height square (kg/m2). Weight measurement was conducted using a weighing scale (SERENE, China) with a capacity of 180 kg. During weight measurement, women were barefoot, standing upright, and wearing light clothing. All measurements were taken in a private environment and performed by a nutritionist.

The following cutoff points were adopted to assess the BMI of adults + middle-aged [18] and elderly women [19]: (1) For adult women: BMI values of 18.5 –24.9 kg/m2 were considered normal weight, while BMI values ≥25.0 kg/m2 were considered overweight. (2) For elderly women: BMI values of 22.0–27.0 kg/m2 were considered normal weight, while BMI values ≥27.0 kg/m2 were considered overweight.

2.3. Individual and Socioeconomic Variables

Socioeconomic variables, such as age, education, marital status, and physical activity, were obtained through individual interviews with the participants. To stratify the participants based on age, they were categorized into three groups: adults (<40 years), middle-aged (40–59.9 years), and elderly (≥60 years). The level of education was classified as incomplete secondary education (individuals with incomplete or complete primary education, including illiterate individuals) and complete secondary education (including technical and higher education). Marital status was classified as either single (including those without a partner, widows, and divorced individuals) or married (stable union). Participants were also classified based on their level of physical exercises as either sedentary (no physical activity or physical activity <3 times/week) or active (physical activity (walking) ≥3 times/week during 1 hr and, in moderate intensity and with rhythmic steps), based on medical records.

2.4. Biological Samples

Clinical attendance was performed in the morning, and all blood samples were collected between 7 and 9 a.m. Blood (10 mL) was collected in K3-EDTA tubes (Vacumed® series), packed in a Styrofoam box with ice, and sent to the Laboratory of Immunology of the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Teófilo Otoni, MG, Brazil. Upon arrival, the samples were refrigerated (4°C), followed by centrifugation at 1,800 rpm for 40 min. Plasma was collected and stored at −80°C.

2.5. CK Activity

The CK activity was determined using a Bioclin Kinetic CK-NAC kit as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil). Briefly, plasma (20 μL) was added to 1 mL of a solution containing imidazole acetate (100 mmol/L pH 6.7), glucose (20 mmol/L), EDTA (2 mmol/L), NADP (2 mmol/L), hexokinase (3,500 U/L), magnesium acetate (10 mmol/L), N-acetylcysteine (20 mmol/L), glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (2,000 U/L), creatine phosphate (30 mmol/L), ADP (2 mmol/L), AMP (5 mmol/L), and diadenosine pentaphosphate (10 mmol/L). After homogenization, the samples were transferred to 96 well plates and incubated for 2 min at 18–25°C, and absorbance was recorded at 340 nm three times every 1 min. CK activity was determined from the absorbance difference (triplicate) multiplied by a correction factor of 8,095 U/L.

2.6. Immunoassays

Circulating levels of the inflammatory mediators CXCL16, IL-33, leptin, and resistin were measured from the plasma samples that were stored at −80°C. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc) were coated with the target monoclonal antibodies (100 μL/well) for 18 hr at 4°C and then washed with PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.5 mM KH2PO4) (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% tween-20. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (200 μL/well) in PBS. After washing, plasma samples were added (100 μL/well) followed by incubation for 18 hr at 4°C. Appropriate biotinylated antibody, diluted in blocking buffer containing 0.05% tween-20, was then added (100 μL/well) and the plates were incubated further for 1 hr at 24°C. This was followed by the addition of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase. After subsequent incubation and washing, chromogenic substrate (o-phenylenediamine (Sigma–Aldrich Brasil Ltda, SP, Brazil) diluted in 0.03 M citrate buffer containing 0.02% of H2O2) was added (100 μL/well) followed by incubation in the dark at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 1M H2SO4 solution (50 μL/well). The plates were read at 450 and 620 nm in a spectrophotometer (Emax_Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All samples were simultaneously measured using Peprotech Immunoassay kits (Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) in triplicates.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Stata (StataCorp, 2013) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) programs were used for the statistical analyses. Descriptive analysis was demonstrated by the distribution of frequencies of categorical socioeconomic variables using Pearson’s chi-square test. For the description of inflammatory markers, the Shapiro–Wilk normality test was performed. To test differences between age groups (adult, middle-aged adult, and elderly), the one-way ANOVA test was used in cases of parametric distribution, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for nonparametric data. Correlations were performed using Spearman’s test for parametric distribution data and Pearson’s test for nonparametric data. The data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Participants

Out of 45 adult women, a high prevalence of overweight 57.7% (n = 26) was observed, while among nine elderly women, 55.5% (n = 5) were normal weight and 44.4% (n = 4) were overweight. Based on socioeconomic variables, a prevalence of completed high school education, stable union, and a sedentary profile was observed among the participants. Physical activity, on the other hand, was more prevalent among normal-weight women compared to overweight women (Table 1).

| Socioeconomic variables | Normal weight (n = 24) | Overweight (n = 30) | Total (n = 54) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Adults/middle-aged (<60 years) | n (%) | 19 (79.1) | 26 (86.7) | 45 (83.3) | 0.462 |

| Elderly (>60 years) | n (%) | 5 (20.9) | 4 (13.3) | 9 (16.7) | |

| Education | |||||

| Incomplete Secondary education | n (%) | 7 (29.1) | 10 (33.3) | 17 (31.4) | 0.743 |

| Complete Secondary education | n (%) | 17 (70.9) | 20 (66.7) | 37 (68.6) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | n (%) | 12 (50) | 14 (46.7) | 26 (48.1) | 0.808 |

| Married | n (%) | 12 (50) | 16 (53.3) | 28 (51.9) | |

| Physical exercise practice | |||||

| No | n (%) | 13 (54.1) | 26 (86.7) | 39 (72.2) | 0.008∗ |

| Yes | n (%) | 11 (45.9) | 4 (13.3) | 15 (27.8) | |

- For the analyses, the chi-square test was used. Data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 ( ∗).

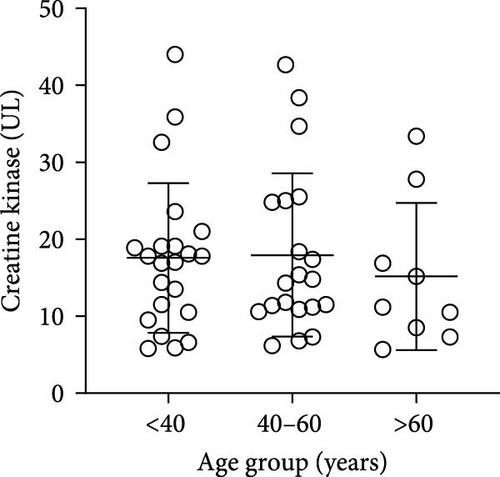

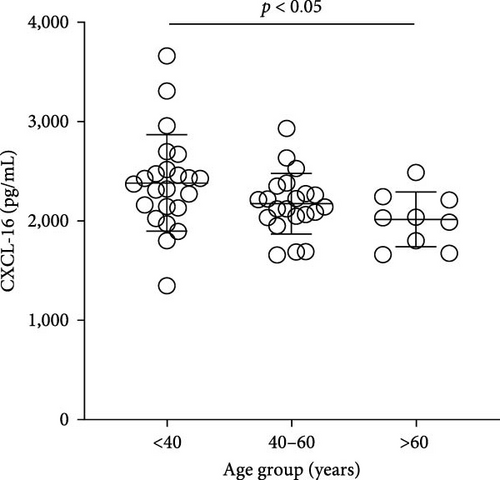

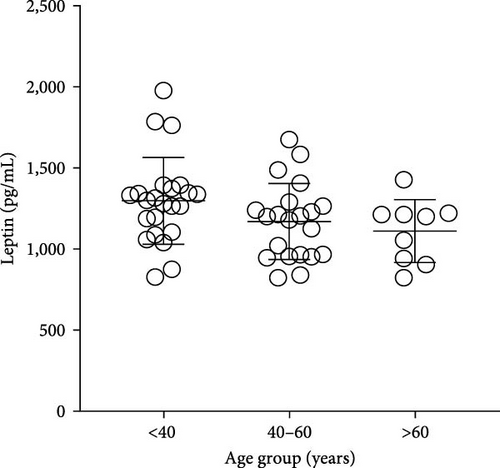

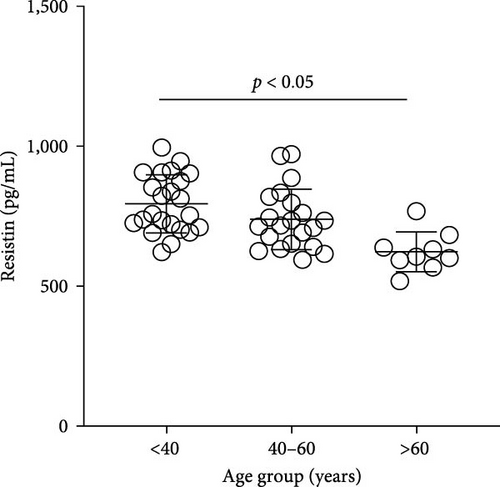

3.2. Correlations between CK, Age, and Anthropometric Parameters

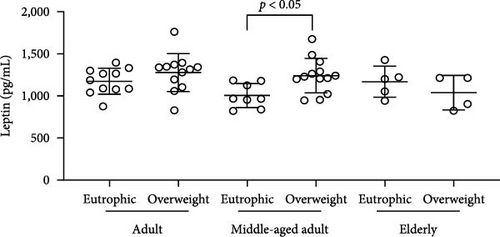

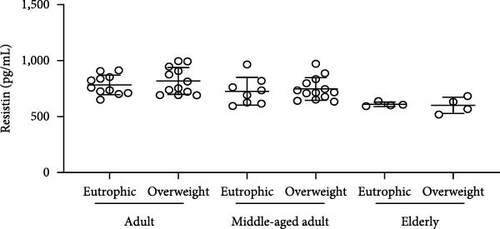

The plasma concentrations of the markers in the different age groups are shown in Figures 1 and 2. We observed that plasma concentrations of CK (Figure 1(a)) and leptin (Figure 2(c)) were balanced regardless of age. On the other hand, IL-33 levels were higher in younger individuals (adults and middle-aged) compared to the elderly subgroup (Figure 2(b)) (p = 0.0171), which was consistent with the patterns observed for CXCL16 (Figure 2(a)) (p = 0.0447) and resistin (Figure 2(d)) (p = 0.0003).

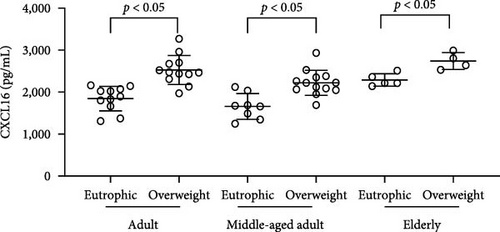

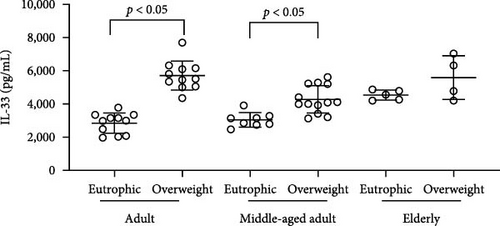

Simultaneously, we also observed that overweight adults and middle-aged individuals had higher plasma levels of CXCL16 (Figure 3(a)) (adults p = <0.0001; middle-aged adult p = 0.0005; elderly p = 0.0058) and IL-33 (Figure 3(b)) (adults p = <0.0001; middle-aged adult p = 0.0010) than normal weight individuals. CK concentrations indicated an overproduction of the marker in adults and the elderly in the presence of overweight (Figure 1(b)) (adults p = 0.0009; elderly p = 0.0355). Plasma leptin (Figure 3(c)) showed significantly higher concentrations only in the overweight middle-aged group compared to the normal weight group (p = 0.0101). Finally, plasma resistin levels did not differ significantly between the various groups (Figure 3(d)).

The plasma concentrations of the markers in different age groups are shown in Figures 1 and 2. We observed that the plasma concentrations of CK (Figure 1(a)) (X2 (2) = 1.090; p = 0.5797) and leptin (Figure 2(c)) (X2 (2) = 5.079; p = 0.0789) were balanced regardless of age. On the other hand, IL-33 levels were lower in the elderly subgroup when compared to adults and middle-aged (X2 (2) = 7.127; p = 0.0283) (Figure 2(b)). Consistently, a similar pattern was observed for CXCL16 (Figure 2(a)) (X2 (2) = 7.110; p = 0.0286) and resistin (Figure 2(d)) (X2 (2) = 15.50; p = 0.0004).

We also observed that overweight adults (t (21) = 5.078; p < 0.0001) and middle-aged (t (19) = 4.148; p = 0.0005) individuals had higher plasma levels of CXCL16 (Figure 3(a)). Simultaneously, the higher plasma levels of IL-33 (Figure 3(b)) were also observed in overweight adults (t (20) = 8.877; p < 0.0001) and middle-aged (t (19) = 3.879; p = 0.001), when compared to normal weight individuals. CK concentrations indicated an overproduction in adults (t (21) = 3.341; p = 0.0031) and in the elderly (t (7) = 2.599; p = 0.0355) in the presence of overweight (Figure 1(b). Plasma leptin (Figure 3(c)) showed significantly higher concentrations only in the overweight middle-aged group when compared to the normal weight group (t (19) = 2.857; p = 0.0101). Finally, plasma resistin levels did not differ significantly among the various groups (Figure 3(d)).

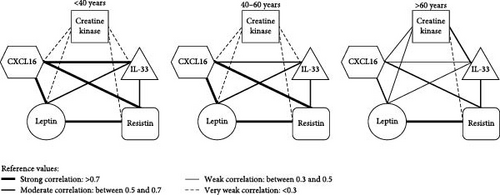

In summary, positive correlations were observed among all age groups, as shown in Figure 4. In adult women, a positive correlation was observed with CXCL16 × IL-33 (r = 0.8005; p < 0.0001), CXCL16 × leptin (r = 0.8891; p < 0.0001), CXCL16× resistin (r = 0.7216; p < 0.0001) and with leptin and resistin (r = 0.7586; p < 0.0001) levels. For middle-aged women, a strong positive correlation was observed with CXCL16 × leptin (r = 0.8288; p < 0.0001), CXCL16 × resistin (r = 0.8204; p < 0.0001) and leptin × resistin (0.8146; p < 0.0001) levels. Weak correlations among distinct inflammatory mediators distributed into different ages (<40, 40–60, and >60 years old) can be found in Table 2.

| Correlations | Adult (<40 years old) | Middle-aged adult (40–60 years old) | Elderly (>60 years old) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL16 vs. IL-33 | r = 0.8005/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.6304/p = 0.0022 ∗ | r = 0.3216/p = 0.3987 |

| CXCL16 vs. leptin | r = 0.8891/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.8288/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.5750/p = 0.1053 |

| CXCL16 vs. resistin | r = 0.7216/p = 0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.8204/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.5348/p = 0.1379 |

| IL-33 vs. leptin | r = 0.6896/p = 0.0003 ∗ | r = 0.5327/p = 0.0129 ∗ | r = 0.3216/p = 0.3987 |

| IL-33 vs. resistin | r = 0.5620/p = 0.0053 ∗ | r = 0.5437/p = 0.0108 ∗ | r = 0.5903/p = 0.0942 |

| Leptin vs. resistin | r = 0.7586/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.8146/p = <0.0001 ∗ | r = 0.8541/p = 0.0034 ∗ |

| CK vs. CXCL16 | r = −0.1628/p = 0.4807 | r = −0.02031/p = 0.9323 | r = 0.4319/p = 0.2457 |

| CK vs. IL-33 | r = −0.02657/p = 0.9066 | r = 0.09323/p = 0.6958 | r = 0.5409/p = 0.1326 |

| CK vs. leptin | r = −0.3151/p = 0.1641 | r = 0.09173/p = 0.7005 | r = 0.3566/p = 0.3461 |

| CK vs. resistin | r = −0.1787/p = 0.4382 | r = 0.1369/p = 0.5649 | r = 0.06759/p = 0.8628 |

- For parametric data, Pearson’s correlation was used, and for nonparametric data, Spearman’s. Data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05 ( ∗).

4. Discussion

The immune response in young, adult, and elderly individuals can either upregulate or downregulate in a natural process, but it is exacerbated by acute and/or chronic diseases. This cross-sectional study highlights the high plasma levels of CXCL16, IL-33, and CK in women without comorbidities or clinical manifestations but categorized according to aging and data evaluated according to nutritional status (normal weight and overweight). Our data showed an increase of plasma CK, IL-33, CXCL16, and leptin related to the overweight in adults and elderly clinically stable women without diagnosed comorbidities or acute/chronic diseases. Part of this data is supported by our previous study, where CXCL16 was proposed as a marker of gain mass and aging in adults and elderly normal weight, overweight, and obesity in adults and elderly women [13, 17]. In both studies, subjects were recruited from different geographical areas and different environmental backgrounds, which could exert a bias on the immune response. However, in the absence of infection or other diseases, the soluble markers were overproduced in elderly and/or overweight women.

The world’s population is aging increasingly over the years globally, and individuals aged 60 or over are growing faster than all other age groups. In parallel, aging has grown together with overweight and/or obesity development, both essential risk factors for death [18]. In our study, we investigate how aging, level of education, marital status, and regular practice of physical exercises could be contributing to the gain of weight in volunteer women without diagnosed diseases. Regular and moderated intensity physical exercise (3x/week for 1 hr) was the only parameter with a statistical difference, with more adhesion to those individuals with normal weight than overweight. According to the WHO 2020 guidelines, adults should undertake 150–300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, which promotes health status in moderate long-term of practicing [19]. Women in regular physical activity can regulate the inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress enzymes in a physiological condition [20]. Most of our sample (72.2%) reject medical recommendations for regular physical activity practice and, even in the absence of infection or metabolic diseases, CK, CXCL16, IL-33, and Leptin were elevated in adults and elderly groups with adults and elderly with overweight.

Both, gain weight and elderly, are associated with marked changes in the immune system, leading to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Gaining weight and being elderly can predict vulnerability to viral, bacterial, and fungal infections [21]. In this sense, the focus of medical attention used to be on obesity due to the risk of cardiovascular comorbidities. Clinically, obesity can be diagnosed by health professionals by measuring BMIs ≥30 kg/m2 [22] or by detecting excessive visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue [23]. However, in overweight individuals who are clinically stable, the diagnosis may not be straightforward, making these individuals prone to unforeseen risks associated with aging.

Senescence also contributes to aging-related metabolic disturbances, such as diabetes, cardiovascular, and neurological disturbances, and depending on the lifestyle, an overweight condition [24]. Overweight condition induces, by adipocytes and systemic cells, chronic and silent production of Th1-type inflammatory mediators (TNF, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-12, CCL2, and CCL5) over the Th2-type (IL-10, IL-22, IL-33, TGF-β) [23, 25]. This immune imbalance can accelerate the development of metabolic and cardiovascular disorders associated with senescence. Previous studies have also pointed out high levels of CXCL16 and obesity in animal models [26], humans [13, 17], and in models of diseases such as coronary comorbidities [27] and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [28]. In this sense, our present study reinforced the high production of CXCL16 in adults and elderly women who are overweight, which suggests a risk of any comorbidity in advance, even in the absence of a current disease.

The IL-33 is another inflammatory marker with a pleiotropic role related to the Th1- and Th2-type inflammatory mediators. It is expressed in different tissues and acts as an “alarmin” in certain diseases, such as obesity [14, 29]. Although previous studies suggest that IL-33 reduces obesity by exerting an anti-inflammatory effect on adipocytes and improving glucose and lipid metabolism [30, 31], elevated plasma concentration has been found in overweight individuals with severe metabolic disturbances [32]. These data were reinforced further, in an experimental model of obesity, when IL-33 was inactivated by caspase 3, preventing the maintenance of the type 2 responses and control of the inflammatory process resulting from excess weight [33].

In this study, CK levels were also elevated in overweight and elderly individuals. Creatine exerts its biological effects through CK, an enzyme that promotes cellular energy production, especially in skeletal muscles [34]. There is a potential link between the concentrations of this enzyme and obesity, suggesting that CK levels could predict obesity and inflammation [35, 36]. Increased CK concentrations have been reported in obese women with reduced muscle mass, a condition known as sarcopenic obesity [37]. CK enhances the mitochondrial respiration rate of brown adipocytes, thereby increasing energy expenditure. As a result, this enzyme regulates energy metabolism, especially in type II muscle fibers, which are associated with insulin resistance and obesity [38, 39].

Finally, in this study, resistin did not show increased levels in overweight individuals, since metabolic disturbances were an exclusion criterion for the volunteers. Indeed, high levels of resistance induce insulin resistance and are associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as arteriosclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatic arthritis, and prehypertension in healthy individuals [40]. Only leptin showed higher levels in middle-aged women in comparison to adults and elderly women. Leptin acts on the brainstem and hypothalamus, regulating food intake and balancing energy, though there are leptin receptors in other sections of the human body. There is no conclusive explanation for leptin elevation only in middle-aged groups overweight, and in this research, it was not our focus investigation on mental health. However, it’s worth noting that high plasma levels of leptin were previously related to severe depressive symptoms in young women [41].

This study has some limitations. First, we chose to include only females because women are the majority of the population that looks for regular medical attendance in disease conditions and prophylactic control [42]. Second, since our study aimed to evaluate the association between exercise, nutrition, inflammatory mediators, and environment, the inclusion of both genders could create a bias. Therefore, our results cannot be extrapolated to what occurs in males. The third limitation was the low adherence of obese women in the study. Then, we excluded this group from the study focusing on overweight women and those presenting normal weight. Finally, researchers did not accompany or evaluate the physical activity practices during the research, which means that this evaluation was not based on valid tools and incorporated risks or bias in physical activity assessment. The classification of sedentary and active was informed by medical doctors based on their clinical records and supported by a formulary filled out by the volunteers during the interview.

In summary, plasma concentrations of CXCL16 and IL-33 are suggested as potential biomarkers for augmenting the BMI in adults, middle-aged adults, and elderly women. Considering the atypical physiological changes and comorbidities related to elderly individuals and considering that middle-aged adults are in a transient phase toward elderly, potential markers, such as CXCL16 and IL-33, could be useful in clinical for early detection of senescence-related signals, enabling timely prognostic or therapeutic interventions.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Vales do Jequitinhonha and Mucuri (UFVJM)—Ethical Assessment (CAAE) #74422717.1.0000.5108.

Disclosure

Current address of Patrícia Regina Soares de Souza: Innovatiz Limited, 85, Great Portland Street, London.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they do not have competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Débora Nonato Miranda de Toledo, Priscilla Vilela dos Santos, Nathalia Sernizon Guimarães, Patrícia Regina Soares de Souza, Caio César de Souza Alves, and André Talvani were responsible for conception, design, writing, and final content; Débora Nonato Miranda de Toledo, Priscilla Vilela dos Santos, Luiza Oliveira Perucci, and Alessandra de Paula Carli were responsible for perform the experiments; Débora Nonato Miranda de Toledo, Priscilla Vilela dos Santos, Patrícia Regina Soares de Souza, Nathalia Sernizon Guimarães, and André Talvani were responsible for data analysis; André Talvani was responsible for funding acquisition. All the authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Pilot Laboratory for Clinical Analysis (LAPAC) for its assistance in the biochemical analysis of the CK test in this research. This study was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq—#405946/2021-0), the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG—APQ-00720-23), and the Federal University of Ouro Preto (UFOP). Débora Nonato Miranda de Toledo thanks UFOP for the scholarship applied to research development and André Talvani (Process #305634/2017-8), Patrícia Regina Soares de Souza (Process# 238277/2012-7), and Priscilla Vilela dos Santos thank CNPq for the research scholarships.

Open Research

Data Availability

The immunological, nutritional, and biochemical data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.