Pediatric Functional Constipation: A New Challenge

Abstract

Functional constipation is a common gastrointestinal disorder worldwide in children, adolescents, and adults. Functional constipation is persistent, difficult, and infrequent hard stooling with incomplete rectal emptying that does not have an identifiable cause, such as underlying illness, anatomical abnormality, or medication, and is a diagnosis of exclusion that causes psychological and physical symptoms in the individual. For early identification of functional constipation in children, a physician must exclude organic causes in children by history, physical examination, and lab studies. Multiple complex pathophysiological mechanisms have been linked to childhood constipation, in which stool-withholding behavior is the most common factor. Toilet training along with osmotic laxative use is currently the common therapy for childhood constipation. Despite being a common condition and with novel therapies such as prosecretory agents, neuromodulation, and transanal irrigation modalities, it is challenging sometimes to manage constipation in children. This is due to a lack of knowledge among parents and children about the nature of constipation which causes poor adherence to the treatment and ultimately worsen the condition. The complaint of constipation in a child should not be ignored as early evaluation and treatment is beneficial for the child’s physical and psychological growth. More research is needed to prevent functional constipation in children. This review article highlights the factors responsible for pediatric functional constipation, its management, novel therapies, and challenges to managing this condition.

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction in which a child experiences a hard, dry, and infrequent defecation with strain and pain. Constipation is functional when there is no organic etiology.

Functional constipation is often described as infrequent and/or difficult bowel movements, deviation from normal frequency, painful defecation, the passage of hard and dry stools, and/or the sensation of incomplete evacuation of stool [1].

1.2. Prevalence

Functional constipation is a common issue in the pediatric population and the prevalence varies in different geographical regions of the world. Data are lacking in different continents of the world such as Africa. It also varies in different age groups, and the peak incidence of constipation is between 2 and 4 years of age.

The etiology of constipation is divided into organic and functional causes which account for 10% and 90%, respectively [2]. In general, 3% of children visit a pediatrician and 25% a pediatric gastroenterologist due to functional constipation [3]. One study revealed that the prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria was 9.5% globally, with the highest number belonging to Europe and America compared to Asian children [4]. The latest evidence reveals a global prevalence of 14.4% when diagnosis of constipation is based on Rome IV criteria [5]. In Asia, the prevalence of functional constipation among children fell within the range of worldwide constipation prevalence, and it varied from 0.7% to 29.6% [6].

Functional constipation has a good prognosis in children with prompt and appropriate treatment. The condition can occur in healthy children 1 year and older and is common in less than 5 years of age [7].

1.3. Normal Defecation Pattern in Children

To identify abnormal patterns of stooling, it is essential to know the normal pattern of defecation in children that is described in many studies. Normal frequency and consistency of stools vary with children depending on their age and diet.

A total of 90% of newborns pass meconium within the first 24 h of life, and in neonates, an average of four soft bowel movements are expected. In breast and formula-fed babies, expect 2–3 soft bowel movements every day. However, breastfed babies can have different patterns of defecation from one bowel daily to bowel with each feeding to no bowel for 5 days. Between 6 months and 1 year of age, an infant usually passes 2 soft poops, and children aged 1–3 years pass one to two soft stools daily. From 4 years onward, expect one soft bowel daily [8].

2. Pathophysiology and Etiology of Functional Constipation in Children

Functional constipation is common in the pediatric population. The pathophysiology is unclear, but there are multifactorial reasons for functional constipation in children depending on their age. It is a disorder of gut-brain interaction with multiple pathophysiological factors. Painful defecation, stressful life events, and emotional and behavioral challenges have been implicated in the development of functional constipation in the pediatric age group [9].

In a small number of cases in children, constipation has an organic cause, for example, a metabolic or endocrine disorder, anorectal anomalies, neuromuscular diseases, or Hirschsprung’s disease [10]. Constipation that occurs at birth or during the neonatal period is most likely due to an underlying organic cause.

There are various etiological factors of functional constipation in the pediatric group which are explained in detail here.

2.1. Defecation Reflex

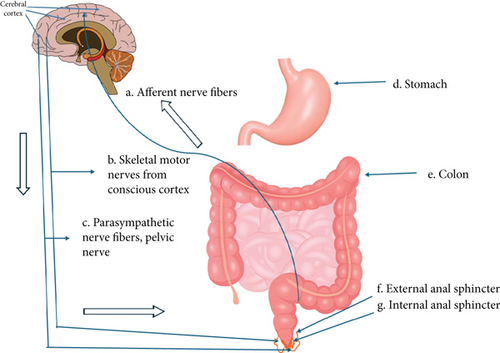

To understand functional constipation, it is crucial to understand the mechanism of normal expulsion of feces, which involves the coordination of the gastrointestinal, nervous, and musculoskeletal systems as shown in Figure 1. The defecation reflex occurs when the internal anal sphincter relaxes and the external anal sphincter contracts. As the rectum is filled with stools, stretch receptors from the nervous system that are in the rectal walls trigger the desire to defecate [11].

2.2. Painful Bowel Movement and Withholding Behavior

Functional constipation, which is 95% of the cases in children, occurs when a child holds feces to prevent painful defecation.

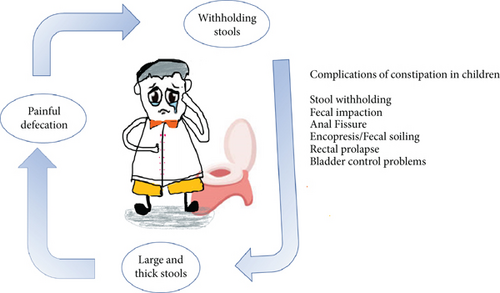

This is a common issue in preschool children when parents initiate toilet training in their child and a frightening and negative episode of painful defection is the usual trigger for developing functional constipation. It may result in retentive behavior of defection to avoid painful pooping [12]. The child contracts the anal sphincter or gluteal muscles by stiffening his or her body, and ultimately, fecal stasis with reabsorption of fluids occurs in the colon that results in harder and larger stools. With time, the rectum stretches to accommodate the large fecal mass, rectal sensation decreases, and fecal incontinence develops [13]. Fecal incontinence also called encopresis or fecal soiling is an involuntary loss of soft stools that pass through an obstructing fecal mass. The pattern of withholding behavior is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Encopresis occurs in 1%–4% of school children and is always related to underlying constipation [14].

2.3. Parental Pressure

Pressure from parents on the child to become toilet-trained leads to anxiety and stress in a child that results in retentive behavior, toilet phobia, and functional constipation [15]. A disturbed parent-child relationship and emotional stress are also a contributing factor in the development of functional constipation. When the defecation urge is constantly ignored, the brain becomes less responsive, and functional constipation occurs.

2.4. Diet

Infants develop constipation when the baby switches from breastfeeding to formula or cow milk. In older children, lack of fiber in the diet results in constipation. Studies support the link between low fiber intake and constipation in children [16]. Similarly, functional constipation is associated with poor water intake, poor diet with a lack of fruits and vegetables, and low physical activity.

2.5. Motility Disorder

The interstitial cell of Cajal, which is the pacemaker in gut peristalsis, is found to be low in children with all forms of constipation. The slow movement of stool through the colon absorbs too much water resulting in dry large feces and constipation. [17].

2.6. Mental Health Disorders

Neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are highly related to childhood constipation [18]. Eating disorders, anxiety, and depression should be ruled out when a teenager has constipation.

In older children, stressful life events cause functional bowel movements such as sexual abuse [19], socioeconomic status, mental health disorders, perianal trauma, withholding feces because of lack of accessible toilets away from home, and when a child or adolescent is busy or playing.

2.7. Genetics

Genetics may play a role in the development of functional constipation, though no specific gene mutations have been discovered yet. Many children have a positive family history of constipation [20].

3. How to Diagnose a Child With Functional Constipation?

A detailed history and physical examination are crucial to making the diagnosis of functional constipation and ruling out organic causes.

3.1. Medical History

- •

The age of onset of symptoms of constipation

- •

Assessing family definition of constipation

- •

The passage of meconium after birth

- •

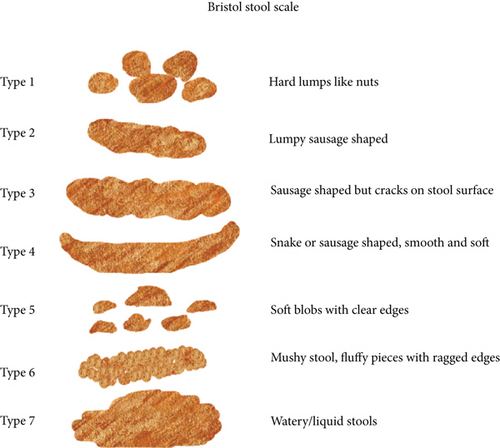

Frequency, consistency, and size of the stool, use a Bristol stool chart (BSC) to classify the stools Figure 3

- •

Pain and strain with pooping

- •

Blood in the stool

- •

Toilet training

- •

Abdominal pain

- •

The posturing of a child while pooping to identify withholding behavior

- •

Fecal soiling/accidents

- •

Recent stressors

- •

Access to the toilet

- •

Systemic symptoms, that is, fever, weight loss, and blood in stool

- •

Details regarding diet, water intake, previous therapies, adherence to therapies, and response to the therapy.

- •

Past medical and surgical history

- •

Family history

- •

Psychological history

- •

Developmental history

Pediatricians sometimes suggest parents make a child’s stool diary to identify functional constipation.

3.2. Physical Examination

- •

General physical examination

- •

Growth parameters of a child

- •

Abdominal examination for distention and palpable fecal material in the lower left quadrant

- •

Spinal examination

- •

Neurological examination including checking for an anal wink and cremasteric reflex.

- •

A digital rectal examination is not routinely recommended in children, but it can be performed when an organic cause is suspected or when there is doubtful constipation [21].

- •

Anal examination for its position, fissures, and anal tags.

3.3. Diagnosis of Pediatric Functional Constipation by BSC and Rome IV Criteria

The use of the BSC in the diagnosis of constipation in children and to assess response to treatment is recommended by a variety of national and international groups [7] as shown in Figure 3.

Additionally, Rome II criteria were established in 1999 for functional constipation in adults. In 2006, Rome III was created for the pediatric group, which was modified to Rome IV in 2016 to identify functional constipation in children [22] shown in Table 1.

| Rome IV criteria for pediatric functional constipation |

|---|

|

3.4. Lab and Imaging Studies

The laboratory is not recommended routinely to diagnose functional constipation [23]; however, a clinician orders thyroid function tests, including free T3, celiac screen, vitamin D status, electrolytes, cow milk allergy testing, lead levels, complete blood count (CBC), ferritin, and urinalysis if there is a suspicious history.

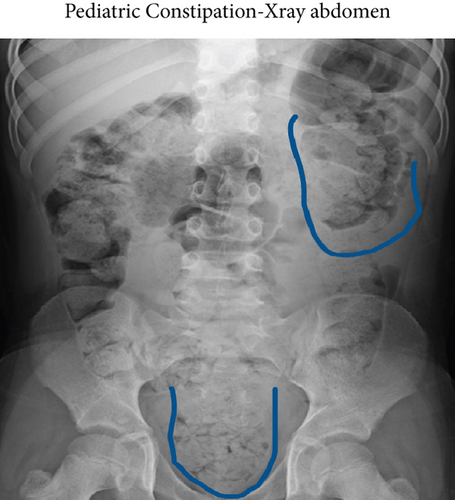

According to the guidelines of the European Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the North American Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, diagnostic imaging studies, that is, X-ray abdomen, are not routinely recommended in children for constipation but can be considered to assess fecal loading in the colon or when the child is obese, as shown in Figure 4.

Furthermore, transabdominal ultrasound can be used to determine fecal impaction when a digital rectal exam is difficult to perform, or rectal impaction is suspected.

Anorectal manometry in refractory constipation may be considered to distinguish between the Hirschsprung disease and functional constipation. Similarly, colonic manometry can help rule out children with colonic neuromuscular disease [24].

Barium enema, rectal biopsy, sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, and colonic transit studies are suggested when organic etiology is suspected.

4. Complication of Functional Constipation

- •

Significant abdominal pain

- •

Anal fissures with bleeding and pain in the perianal area

- •

Appetite suppression

- •

Growth suppression due to decreased appetite

- •

Encopresis/fecal incontinence

- •

Low self-esteem due to fecal soiling, family disruption, social isolation, and emotional and behavioral issues in adolescents [25]

- •

Poor academic performance

- •

Overweight and obesity [26]

- •

Fat deficiency, stunted growth [27]

- •

Rectal prolapse, in which the rectal part comes out of the anus.

- •

Urinary incontinence, bladder overactivity, recurrent urinary tract infections, and deterioration of vesicoureteral reflux [28]

5. Management of Pediatric Functional Constipation

Functional constipation in children is a challenge for pediatricians, as the rate of relapse of functional constipation is high in children. Early intervention improves the prognosis of functional constipation in children [29]. With a comprehensive approach and systemic intervention, a child can achieve independent bowel emptying. Regular follow-ups and adherence to treatment are necessary to achieve good results and to prevent recurrences.

The treatment of functional constipation is largely unchanged but there is a need for further research and studies to move away from considering the effectiveness of single interventions and individual children’s characteristics must be considered in future studies [30].

- 1.

Family and child education

- 2.

(1) Diet, (2) hydration, and (3) physical activity

- 3.

(1) Disimpaction (clean out) phase and (2) maintenance phase

- 4.

(1) Noval therapies and (2) neuromodulation

- 5.

(1) Probiotics and (2) prebiotics

- 6.

Surgery

6. Family/Child Education

Counseling/education of the family and the child is essential and the first step in the treatment of functional constipation [32]. By explaining the mechanism and factors that cause functional constipation in children, parents can easily understand the situation and it helps them to make better plans to treat childhood constipation.

6.1. Regular Toilet Habits

Physicians often encourage parents to motivate their child to sit on the toilet three times a day, especially after 20 min of meal intake for 5 min to establish a routine and prevent withholding stool behavior. The bowel must be trained in such a way that it becomes conditioned to work on its own, a concept known as “bowel retraining” [20]. Toilet time should be comfortable, with foot support, no distracting objects while pooping, and support them to focus on bearing down. Parents should be encouraged to keep a record of the child’s bowel, not to punish a child, and to be positive and supportive of their child during this journey of constipation [33].

7. Diet, Hydration, and Physical Activity

7.1. Diet

Children are encouraged to eat fiber-rich foods such as fruits (apples with peels, raspberries, grapes, guava, pineapple, etc.), raw vegetables (broccoli, avocado, spinach, salads, etc.), whole grains, nuts, beans, and legumes. A fiber-rich diet is a better source for improving constipation in children [34].

7.1.1. Fiber-Rich Food

Introducing fiber-rich foods early in a child’s diet can establish healthy eating habits that contribute to lifelong digestive health. Foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes are excellent sources of fiber and should be included in a child’s diet regularly. Introduce fiber gradually to a child’s diet to prevent gastrointestinal discomfort or bloating. Certain fibers (especially psyllium in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)) have shown advantageous effects in children with gastrointestinal disorders but there is limited evidence available for their recommendation [35].

Dietary fiber plays a crucial role in relieving functional constipation in children as fiber adds bulk to stool, making it easier to pass through the digestive tract. This bulkiness helps to stimulate bowel movements and prevents constipation. Additionally, fiber absorbs water, which softens the stool, further aiding in its passage.

Fiber helps regulate bowel movements by promoting regularity. It does so by adding volume to the stool and stimulating the muscles in the intestines, which helps move waste through the digestive system more efficiently.

Certain types of fiber act as prebiotics, which means they provide nourishment for beneficial bacteria in the gut. A healthy balance of gut bacteria is essential for proper digestion and regular bowel movements. Fiber-rich foods promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut, which in turn contributes to overall digestive health.

The requirements of dietary fiber in infants and children are still in studies and there is no consensus on this [36].

In 1995, Williams et al. suggested fiber consumption over 2 years old as age plus 5 g per day, a maximum of up to 10 g per day.

Several studies have been performed on the effect of fiber intake in children [37].

European Food Safety Authority suggests 10 g per day of fiber daily for 1–3 years of age, 14–16 g per day between 4 and 10 years of age, and 19 g per day of fiber daily for 11 to 14 years of age children [36].

7.1.2. Limiting Constipated Foods

Processed foods, dairy products, and foods high in refined sugars should be reduced when a child or adolescent suffers from constipation.

7.2. Hydration

Plenty of water to maintain proper hydration is crucial for child health and to improve constipation. The amount of water consumed depends on the age, weight, activity status of the child, and the heat and humidity in the environment.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 4–8 oz of water can be introduced for a 6-month- to 1-year-old infant. A 1- to 3-year-old child needs four cups of water per day, a 4- to 8-year-old needs five cups of water per day, and 2 L of water is recommended for older children.

7.3. Physical Activity

Encourage physical activity, exercise, and playtime in children that stimulate bowel movements and promote regularity [38]. Regular physical activity promotes intestinal activity, and body awareness and reduces stress.

Pelvic floor muscle (PFM) exercises are an effective adjuvant treatment option for constipation relief and bladder bowel dysfunction (BBD) in children. It helps children to understand the action of pelvic musculature and synergistic abdominal and perianal function. PFM are simple exercises that teach the children to relax these muscles during defecation [39].

Physiotherapy helps relieve early symptoms of functional constipation in children [40]. It aids in making coordination between abdominal and pelvic floor musculature.

Motivate the children to use squatting posture while using the toilet as this posture relax the pelvic muscles and helps in stool elimination by improving the rectal anal angle [41].

7.4. Disimpaction

In this phase, the child needs to drink a lot of fluids. Fluids in the form of electrolytes such as apple juice, prune juice, and orange juice are encouraged that are rich in sorbitol and aid in relieving constipation [42].

Disimpaction with oral or rectal medication or a combination of both before maintenance therapy is crucial [43]. Always follow the doctor’s instructions for the proper dosage and use of laxatives. PEG 3350 is a commonly used laxative in pediatric settings and Pico Salax. Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution, mineral oil, or both are effective in oral disimpaction [44].

In severe cases, a child may need hospitalization for a short time to receive a stronger enema to clean the bowel.

For the rectal route, a glycerine suppository is used in infants and bisacodyl in older children. Other enemas used in children are phosphate soda enemas, saline enemas, or mineral oil enemas followed by phosphate enemas.

Transanal irrigation is used for children who are unresponsive to pharmacological therapy or children with neurogenic bowel disorders or anorectal malformations [45]. It involves inserting a cone or catheter in the rectum and injecting water into the colon for its complete cleaning. Studies reveal that this method is 78% safe and effective [5].

7.5. Maintenance Phase

Physicians often advise parents to continue medications/stool softeners for 3 months, 6 months, or 12 months. The goal is to achieve one soft stool per day in a child. Stool softeners are generally safe to use in children unless monitored by a physician.

Treatment options for functional constipation in children are mentioned in Table 2, and doses are according to up-to-date November 2022 data [46].

Stimulant laxatives Oral laxatives |

|---|

| First-line treatment |

|

| Osmotic laxatives |

| Additional or second-line treatment |

|

| Rectal enemas |

|

7.6. Novel Therapies

Prosecretory agents, such as lubiprostone [47] and linaclotide, and plecanatide and serotonergic agents, such as serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), have been tried in functional childhood constipation, but more research studies need to be conducted for the safety and efficacy of these medications in all age groups of children.

Linaclotide, a guanylate cyclase C agonist, has been approved by the United States of America (USA), Food Drug Administration (FDA) in the pediatric population for functional constipation [48].

Bile acids may help relieve functional constipation in children [49]. Elobixibat is a novel drug that is helpful in adult constipation, but its use in the pediatric population needs research.

Cholinesterase inhibitors such as pyridostigmine used in children with gastrointestinal motility disorders showed improvement [50].

Similarly, biofeedback therapy and Botox/botulinum toxin injection have been used in children with the Hirschsprung disease or internal anal sphincter achalasia [51], but its use in childhood functional constipation does not make any difference [52].

Future comparative randomized clinical trials are needed to further clarify the role of newer (prokinetic and prosecretory) pharmacological agents for the management of pediatric functional constipation.

7.7. Neuromodulation Therapy

Neuromodulation is defined as an alteration in nerve activity through targeted delivery of a stimulus, such as electrical stimulation or chemical agents, to specific neurological sites in the body. It is carried out for the normalization or modulation of the nerve tissue function.

Neurostimulation is a new technique for the treatment of intestinal and bladder dysfunction. It is used as an adjuvant therapy in refractory cases of pediatric functional constipation [53].

Transcutaneous neuromodulation is a less expensive, noninvasive, and effective modality to treat refractory constipation and retentive fecal incontinence in children [54]. It works at different neural levels for the restoration of balance between the excitatory and inhibitory regulations at the central and peripheral nervous systems. A current is used to stimulate the nerve fibers that improve the peristalsis through parasympathetic activation.

Different portable devices can be used for neuromodulation therapy by parents or guardians using interferential or pulsed current with sacral stimulation [54].

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) is effective in some studies of childhood intractable and slow transit constipation [53]. It is an effective invasive therapeutic technique for refractory constipation and fecal incontinence in children and adolescents [55]. It involves programmable stimulator implantation subcutaneously, which delivers low-amplitude electrical stimulation via a lead to the sacral nerve, usually accessed via the S3 foramen [56].

A 2020 pilot study demonstrated significant improvement in 17 constipated children with noninvasive sacral nerve stimulation [57]. One another study revealed improvement in abdominal pain and stool frequency in 30 constipated children with SNM treatment for 3 weeks and effects remained for 22 months in 48% of children [58].

7.8. Probiotics

Probiotics are living micro-organisms that provide health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts to the host, by improving or restoring the gut microbiota. Consider incorporating probiotics into the child’s diet as probiotics may offer some benefits in functional constipation [59]. The role of gut bacteria in functional gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS has been well-described [60].

Commonly used probiotics containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium show therapeutic potential for functional constipation and improve stool frequency and consistency [59].

Probiotics may alter the gut microbiota, gut sensation, motility function, and intraluminal environment by increasing the end products of bacterial fermentation which affects the secretion and absorption of water and electrolytes, produces lactate and short-chain fatty acids, and reduces the intraluminal pH [61]. However, research on the role of probiotics in the relief of constipation is highly needed [62, 63].

The research in 2020 included 12 articles, in which 15 strains of probiotics were studied in constipated children who showed irregular benefits of probiotics in bowel frequency/consistency, abdominal pain, and flatulence [64]. Despite the advantageous effects of probiotics on certain intestinal habitats, there is still no evidence for their use in pediatric functional constipation.

Current evidence does not advocate the efficacy of probiotics (healthy gut bacteria) and synbiotics (a mixture of probiotics and prebiotics) used in treating functional constipation in children [61].

7.9. Prebiotics

Prebiotics are compounds in food that promote the growth and activity of essential microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. They are broken down by the gut microbiome and release the byproducts called short-chain fatty acids. Consumption of prebiotics facilitates the health of the host. Prebiotics are naturally found in certain foods such as bananas, onion, garlic, and asparagus [65].

The Global Prebiotic Association (GPA) in 2021 defined a prebiotic as an ingredient or a product that is utilized in the microbiota producing a health or performance benefit to human health.

Recently, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study for the effect of prebiotics on functional constipation in children was conducted for the age group of 1–5 years, and it hypothesized that prebiotics oligosaccharides are beneficial in relieving symptoms of functional constipation in children [66]. However, sufficient evidence is lacking, and large studies are required to investigate the beneficial effects of prebiotics on functional constipation in children.

8. Surgery

Refractory or severe constipation may need surgical intervention [67]. Antegrade continence enemas, sacral nerve stimulation, colonic resection, and intestinal diversion are included in the surgical management of constipation [68].

9. Challenges in the Pediatric Functional Constipation

- •

Limited communication: Young children may have difficulty expressing their discomfort or explaining their symptoms, making it challenging for caregivers to recognize and address constipation early on.

- •

Complex etiology: Functional constipation in children often has multifactorial causes, including dietary factors, inadequate fluid intake, withholding behaviors, psychological factors, and underlying medical conditions. Identifying and addressing these factors requires a comprehensive evaluation and individualized treatment approach [69].

- •

Resistance to treatment: Children with constipation may resist treatment interventions, such as changes in diet, increased fluid intake, or stool softeners. This resistance can be due to fear, discomfort, or anxiety related to bowel movements or changes in routine.

- •

Potential side effects of medications: While medications such as laxatives may be necessary for managing constipation in some cases, they can have side effects such as abdominal cramping, diarrhea, or electrolyte imbalances. Balancing the benefits and risks of medication use in children requires careful monitoring and adjustment by healthcare providers [70].

- •

Reluctance to toilet train: Toilet training can be challenging for both children and caregivers, particularly if constipation or painful bowel movements have created negative associations with using the toilet. Encouraging proper toileting habits and overcoming resistance to toilet training requires patience, consistency, and positive reinforcement. Rewarding the child for defecation improves the outcome of functional constipation [70].

- •

Parental knowledge and understanding: Many parents may lack knowledge about childhood constipation, its causes, and appropriate management strategies. Educating parents about the importance of dietary fiber, fluid intake, regular toileting habits, and the role of behavioral interventions can empower them to support their children effectively.

- •

Long-term management: Functional constipation in children often requires long-term management to prevent recurrence and maintain bowel regularity. However, sustaining treatment adherence and maintaining consistency in lifestyle modifications can be challenging for both children and caregivers over time.

- •

Organic causes: In some cases, there is an underlying organic etiology for constipation in children. Identifying and addressing the underlying conditions is essential for effective treatment but may require additional diagnostic testing and specialized care.

- •

Mental health factors: Constipation can have psychological effects on children and adolescents [71], leading to anxiety, stress, or low self-esteem, especially if it results in embarrassing accidents or social stigma. Psychological and emotional distress caused by functional constipation in adolescents and children is a concern for families and children [72]. Addressing these psychological factors alongside physical symptoms is crucial for comprehensive treatment.

Addressing these challenges requires a collaborative approach involving healthcare providers, caregivers, and the child. Tailoring treatment strategies to the individual needs and circumstances of each child and providing ongoing support and education can help overcome these challenges and improve outcomes for children with functional constipation.

10. Conclusion

Childhood functional constipation is a common complaint and is responsible for frequent visits to the doctor that cause expenditure and burden on the healthcare system. It is challenging for healthcare professionals and caregivers to manage a child’s constipation due to its long-term management and poor adherence to the treatment. Although the risk of recurrence of constipation in children is high, the prognosis of a child with functional constipation is good with early diagnosis and management.

In children’s functional constipation, there is no underlying organic etiology, and withholding behavior is a common etiological factor.

Toilet training, fiber-rich food, adequate water intake, and physical activity are the main treatment pillars of functional constipation. Polyethylene glycol is the medication of first choice for both disimpaction and maintenance therapy and it should be continued with doctor advice for some specific period. Modern therapies need more scientific studies to support their use in children’s functional constipation.

More preventive strategies for functional constipation in children must be discovered that not only can improve the quality of life of a child and parental worry but also can reduce the cost of health care. General practitioners and pediatricians need to provide necessary education to parents on how to nurture a child with a healthy gut, and this can make a significant difference in the lives of the pediatric population.

In summary, addressing constipation in children requires a multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals, caregivers, and the child. Early recognition, appropriate management strategies, and ongoing support are essential for alleviating symptoms, preventing complications, and improving the child’s quality of life.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.