Does Lifestyle Affect Isotretinoin Tolerance in Patients with Acne? A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

Isotretinoin (ISO) is a synthetic retinoid approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Despite satisfactory results, it is still controversial due to numerous adverse events (AE). However, there is a lack of literature examining the factors affecting the frequency and severity of these AEs. Lifestyle patterns may have an impact as they have the greatest impact on a person’s overall health. The aim of the research is to evaluate the impact of lifestyle patterns on the occurrence and severity of systemic ISO AEs in patients suffering from acne. A retrospective cohort study was conducted using a database of collected information about adults diagnosed with acne and treated with systemic ISO. Patients were divided into several groups according to their smoking status (nonsmokers, smokers), BMI (normal weight, overweight), physical activity (active, inactive), and compliance with the Mediterranean diet (adherent, not adherent). Considering all mentioned lifestyle factors, responders were categorized into healthy and unhealthy lifestyle groups. 124 adults with acne, undergoing systemic ISO therapy, made up the study group. There were generally no significant differences in patient characteristics across groups (P > 0.05). Almost all classes and subclasses of AEs showed no significant differences in groups (P > 0.05). ISO is still the most effective drug in the treatment of acne and despite the AEs, therapy should not be abandoned. Moreover, lifestyle factors such as physical activity, smoking, and eating habits do not affect the incidence and severity of AEs, which proves the safety of ISO regardless of unhealthy habits.

1. Introduction

Isotretinoin (ISO), a highly effective oral prescription synthetic retinoid derived from vitamin A, is the only approved medication to treat severe, resistant, nodular, phlegmonosa, conglobata, and unresponsive to systemic treatment with tetracyclines and macrolides acne. ISO is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) microsomal enzyme system to three main metabolites: 4-oxo-isotretinoin, retinoic acid (tretinoin), and 4-oxo-retinoic acid (4-oxo-tretinoin) [1, 2].

The exact mechanism of ISO action is hypothetical. Its pharmacodynamics can be based among others on binding to the retinoic acid nuclear receptors gamma (RAR-γ), inhibition of the production of cytokeratins 1, 10, and 14, filaggrin and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), increase in cytokeratins 7, 13, and 19, laminin B1, and interleukin 1 (IL-1) and interaction with Forkhead Box Protein O1 (FOXO1). Additionally, it may also interface with nuclear transcription factors, which regulates gene expression affecting proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and different cell renewal. Regardless of which element of action is dominant, ISO therapy affects all the four primary etiological factors involved in acne. It makes the skin microenvironment less hospitable to bacteria, exerts an anti-inflammatory effect, decreases sebaceous gland activity, and normalizes follicular desquamation. Nevertheless, the above effects are mediated in widely varying cell types, giving rise to a number of adverse events (AE) like mucocutaneous side effects, the telogen effluvium, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) release, the release of transaminase, neural crest or hippocampus cells alteration, and inflammatory bowel disease or conjunctival dryness. The most serious is teratogenicity [3].

Mucocutaneous AEs (mainly dryness) relate to the basic action of ISO, which is the inhibition of the activity of the sebaceous glands. This process involves multiple pathways and also has anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory properties through down-regulation of TLR 2 and 4 and Th lymphocytes [4, 5]. Additionally, acne treatment can affect the hair follicles, causing telogen effluvium, which can result in alopecia [6]. Moreover, ISO affects the cell cycle, proper differentiation, and apoptosis by modulating levels of the transcription factor, FoxO3a, thereby increasing the expression of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL). In muscle tissue, it may explain muscle pain and elevated creatine kinase (CK) during acne treatment [7]. Additionally, retinoids are liposoluble and cross the haemato-encephalic barrier. Thus, ISO reduces hippocampal neurogenesis and reduces serotonergic signaling, leading to depressive symptoms [8]. The most serious AE is teratogenicity. The explanatory hypothesis could be the apoptosis of neural crest cells caused by overexpression of a proapoptotic transcription factor, p53 gene [7, 9] In fact, apoptosis appears to be crucial in many other mechanisms responsible for ISO AEs, affecting many cell types, including sebaceous cells, neural crest cells, hippocampal cells, keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, hepatocytes, muscle cells, and intestinal epithelial cells. The magnitude of ISO-induced apoptotic signaling seems to depend on genetic variations, such as RARA polymorphism, which explains the enhanced susceptibility for individual apoptosis-related AEs in subgroups with genetic variations [7].

Although ISO is effective in reducing acne lesions, AEs are common [10]. The course of acne can be also modified through lifestyle modification. Previous studies have shown a relationship between acne severity and genetics and lifestyle (age, diet, stress, sleep, smoking, physical activity, obesity, etc.) [11, 12]. However, there is a lack of literature analyzing whether lifestyle factors (e.g., physical activity, eating patterns, and smoking) can affect the frequency and severity of AEs.

1.1. Objectives

The aim of the present study is to analyze the relationship between tolerance of ISO therapy and lifestyle assessed by physical activity, diet, body mass index (BMI), and smoking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Chair and Department of Dermatology, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Clinical Immunology Collegium Medicum University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn in Poland. The database was created using an anonymous online survey distributed using Google Forms as a tool and by doctors at our clinic and Facebook as the platform. We utilized collected information regarding adult patients diagnosed with acne vulgaris and treated with systemic ISO. The research included both patients undergoing ISO therapy (at least 30 days after the start of the treatment) and those who completed the treatment. Each patient submitted their informed consent to participate in the trial, and our institution also granted its approval. Participation was voluntary, and participants did not receive financial remuneration for participation. Due to the study design, it was not formally supervised by a University Bioethics Committee in line with its policy.

2.2. Outcomes Measurement

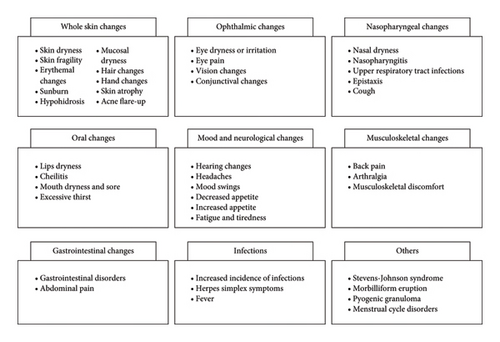

The following information was collected: patient’s biological sex, chronological age, body weight, height, education degree, domicile size, income, smoking status, and brand of administered ISO. According to previous systematic review, AEs were categorized into nine classes and 41 subclasses: whole skin changes (skin dryness, skin fragility, erythemal changes, sunburn, hypohidrosis, mucosal dryness, hair changes, hand changes, skin atrophy, and acne flare-up), ophthalmic changes (eye dryness or irritation, eye pain, vision changes, and conjunctival changes), nasopharyngeal changes (nasal dryness, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, epistaxis, and cough), oral changes (lips dryness, cheilitis, mouth dryness and sore, and excessive thirst), mood and neurological changes (hearing changes, headaches, mood swings, decreased appetite, increased appetite, fatigue, and tiredness), musculoskeletal changes (back pain, arthralgia, and musculoskeletal discomfort), gastrointestinal changes (gastrointestinal disorders and abdominal pain), infections (increased incidence of infections, herpes simplex symptoms, and fever), and others (Stevens–Johnson syndrome, morbilliform eruption, pyogenic granuloma, and menstrual cycle disorders) (Figure 1) [13].

The occurrence and severity of AEs were assessed using a five-point scale: no symptoms, mild symptoms, moderate symptoms, severe symptoms, and very severe symptoms. As a result of the small groups, the authors decided to combine some of the responses to establish a three-point scale of severity of AEs: none, low severity, and high severity.

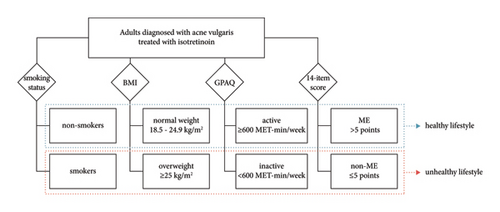

Smoking status separated patients into two groups: smokers (including current smokers and ex-smokers) and nonsmokers (containing: never smokers, nondaily smokers, occasional, and social smokers). BMI was estimated according to a standard formula, and patients were divided into two groups: normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and overweight (≥25 kg/m2). Respondents also completed two questionnaires: the PREDIMED validated 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Questionnaire and the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [14, 15]. Patients were separated into two groups based on the 14-item score: those who adhere to the Mediterranean diet (MD group) and those who do not (non-MD group), with five points or less. The GPAQ classified patients into two categories: active and inactive, with a cut-off of 600 metabolic equivalents-minutes per week (MET-min/week). Considering the smoking status, BMI, physical activity, and compliance with the Mediterranean diet, respondents were divided into two groups: those who followed healthy habits (a healthy lifestyle group) and those who did not (unhealthy lifestyle). The patient in the healthy lifestyle group demonstrates more healthy than hazardous patterns (>2) (Figure 2).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Using descriptive statistics, the database was analyzed. All calculations were preceded by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. To compare the values of the same parameter between the groups, the t-Student test for independent groups or the Mann–Whitney U test (parametric data) and the chi-square test (nonparametric data) were used. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was performed using Statistica (data analysis software system), version 13, https://statistica.io (accessed March 4, 2023) TIBCO Software Inc., Krakow, Poland (2017).

3. Results

The study involved 124 adults diagnosed with acne vulgaris and treated with systemic ISO. The therapy was conducted following Polish recommendations for the treatment of acne vulgaris [16]. The study group consisted of 112 women (90%) and 12 men. The median age was 24 years (interquartile range-IQR, 22–28). The minimum age of participants was 13 years, and the maximum age was 50 years.

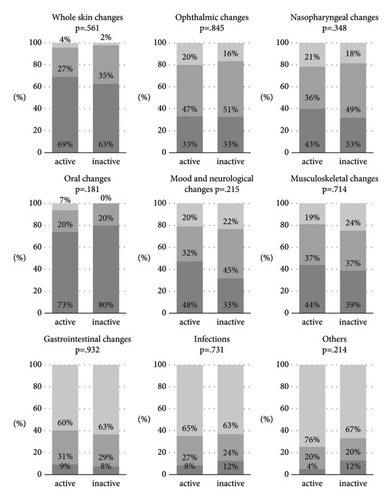

The physically active group consisted of 75 people (60%): 67 women (89%) and eight men, whereas the inactive group consisted of 49 (40%): 45 women (92%) and five men. There were no statistically significant differences in the patient characteristics (P > 0.05) other than smoking status (greater frequency of smoking in the active group) (Table S1). No statistically significant differences in the incidence and severity of AEs (P > 0.05) were observed, except for two subclasses: excessive thirst (higher incidence in the inactive group) and mood swings (higher incidence and severity in the active group) (Figure 3, Figure S1).

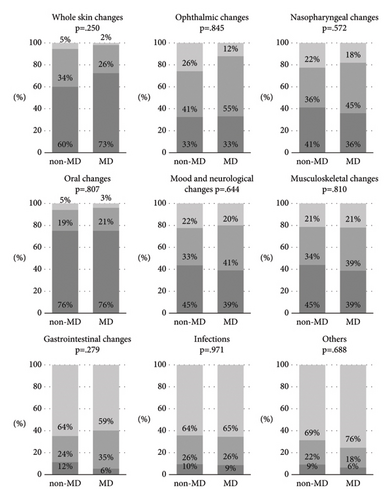

There were 66 individuals (53%) who followed the Mediterranean diet: 59 women (89%) and seven men, and 68 (47%) who did not: 53 women (91%) and five men. Except for the size of the place of residence (the MD group resided in larger cities), there were no statistically significant differences in the patient characteristics (P > 0.05) (Table S2). There were no statistically significant differences in the occurrence and severity of AEs (P > 0.05) aside from two subclasses: hyperhidrosis (higher incidence in the non-MD group) and musculoskeletal discomfort (higher severity in the non-MD group) (Figure 4, Figure S2).

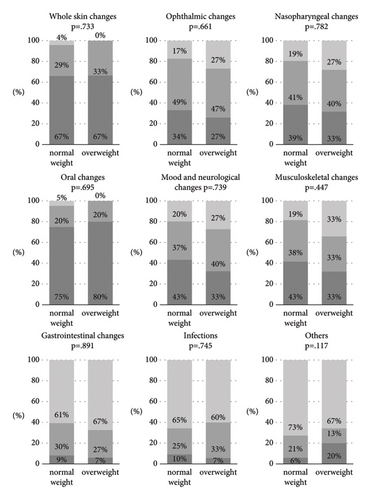

According to BMI, there were 109 people (88%) in the normal weight category, including 98 women (90%) and 11 men, and 15 (12%) in the overweight group, including 14 women (93%) and one male. There were no statistically significant differences between both patient characteristics and incidence and severity of AEs (P > 0.05) (Table S3, Figure 5, Figure S3).

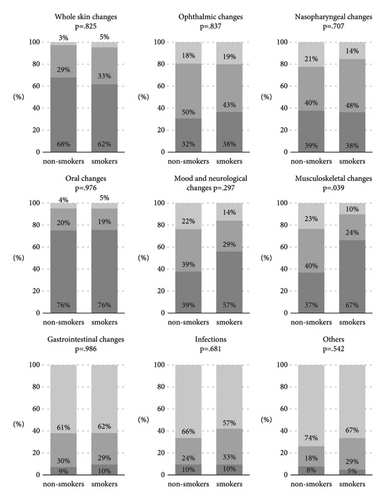

There were 103 individuals in the nonsmoking group (83%): 94 women (91%) and nine men; and there were 21 persons in the smoking group (17%): 18 women (86%) and three men. Apart from the mean MET-min/week (smokers were more active), there were no statistically significant differences between the characteristics of the patients (P > 0.05) (Table S4). There were no statistically significant differences in the incidence and severity of AEs (P > 0.05), except for one class: musculoskeletal changes (greater prevalence and severity across the smokers) (Figure 6, Figure S4).

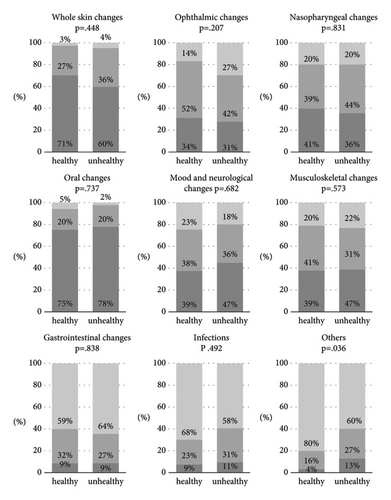

The healthy lifestyle group included 79 participants (64%): 70 women (89%) and nine men, whereas the unhealthy lifestyle group had 45 participants (36%): 42 women (93%) and three men. There were no statistically significant differences between the patient characteristics (P > 0.05) other than the average 14-item score (the healthy lifestyle group followed the Mediterranean diet more) and smoking status (the healthy lifestyle group smoked less frequently) (Table S5). Except for one class: other, which had a higher prevalence and severity in the unhealthy group, and two subclasses: mucosal dryness and menstrual cycle disorders (higher severity in the unhealthy group), there were no statistically significant differences in the frequency and severity of AEs (P > 0.05) (Figure 7, Figure S5).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of lifestyle on the occurrence and severity of systemic ISO adverse events in patients diagnosed with acne. The study group consisted of 124 adults diagnosed with acne and subjected to systemic ISO therapy. Taking into account lifestyle factors (smoking, BMI, physical activity, and Mediterranean diet), participants were divided into healthy and unhealthy lifestyle groups. There were almost no significant differences in the occurrence and severity of ISO adverse events between these groups (P > 0.05).

4.1. Physical Activity

A rare AE of ISO is rhabdomyolysis, which is usually triggered by the synergistic effect of a systemically administered drug and physical activity [17, 18]. Our finding is that there is no correlation in the exacerbation of musculoskeletal-related AEs and physical activity. This only underscores the conclusion that ISO is a safe drug. Moreover, it is worth considering that physical activity itself is a proven factor in the pathogenesis of acne. Physical activity helps maintain a proper body weight and reduces inflammation [19, 20]. Therefore, it is extremely important not to forbid patients from physical activity but rather to encourage it. The only statistically significant differences were observed in excessive thirst, which are predominated in the inactive group, and in mood swings in the active group. A potential paradigm could be that patients who exercise consume more fluids during physical activity, by which they moisten their mucous membranes, which in the case of dry mouth and lips may reduce the feeling of excessive thirst, while inactive patients experience it excessively. There does not appear to be a direct link between depression and ISO treatment. The appearance of mood disorders may be only a rare idiosyncratic side effect [21]. The positive correlation of physical activity and higher incidence and severity of mood swings for our results may be coincidental, independent of therapy, and is solely the subjective opinion of patients completing the questionnaire.

4.2. The Mediterranean Diet

The published literature, though sometimes limited in study design, shows inconsistent results on the role of diet in acne. However, a growing number of studies point to diet as a factor in acne severity. In studies, omega-3 fatty acids, low glycemic diets, and probiotics have been shown to have an effect on acne reduction, while products such as whey protein and casein-containing milk, among others, may exacerbate skin lesions by affecting insulinotropic and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) pathways [22]. The Mediterranean diet is characterized by a low glycemic index due to its low carbohydrate content, high oil and vegetable content, and moderate fish consumption. Therefore, it provides a significant source of antioxidant vitamins and acts on the systemic IGF-1 pathway by reducing its levels. Thus, it may exhibit a protective role in acne pathogenesis [23, 24]. However, studies on the effect of diet on the occurrence and severity of AEs associated with ISO therapy are not available. According to our results, more common, among patients not adhering to the Mediterranean diet, was hyperhidrosis. Sweating plays a key role in regulating human body temperature, removing excess micronutrients, waste products of metabolic processes, and toxins from the body. Patients who did not adhere to the Mediterranean diet were more than likely simply eating unhealthy diets, which increased sweating to eliminate unnecessary metabolic waste products [25]. In addition, we observed a higher severity of the musculoskeletal discomfort among the non-MD group. Many studies have observed a reduction in musculoskeletal pain with nutritional interventions, among others, the Mediterranean diet [26]. To reduce and prevent discomfort, it would be worthwhile to educate patients about the impact of a healthy diet. In other AEs, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups.

4.3. BMI

Obesity itself has been positively linked to acne aggravation, as well as by increasing the secretion of IGF-1 in the body and affecting insulin resistance [19]. ISO therapy increases serum levels of adiponectin and leptin but does not affect ghrelin levels and thus does not change patients’ BMI or affect body weight [27]. Furthermore, ISO AEs do not increase according to patients′ BMI.

4.4. Smoking

Previous studies have proven a correspondence of acne severity in smokers and ex-smokers, which may be due to increased levels of inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines. Controversial results show that severe acne appeared less frequently in smokers [13]. Smoking also increases the likelihood of acne recurrence after treatment, a slow response or apparent lack of response to ISO [28]. Nevertheless, smoking is a proven etiologically relevant factor in the origin of acne inversa (hidradenitis suppurativa) [29–31]. Moreover, it is well known that tobacco smoking has negative effects on the health outcomes of the musculoskeletal system [32]. The higher incidence and severity of musculoskeletal symptoms in the smoking group according to our results may not necessarily be related to the ISO intervention but to smoking per se.

4.5. Lifestyle

Considering that other AEs that occur with ISO treatment extremely rarely are attributed to individual predisposition to the rise of these syndromes rather than a direct drug-response relationship. Nevertheless, given that these events occurred more frequently in the unhealthy group, it would be worthwhile to conduct more research on a broader group of respondents, as simple lifestyle alterations could potentially prevent certain of them from manifesting. Studies confirm that menstrual cycle disorders are influenced by factors such as smoking, obesity, and stress. WHO outlines that 60% of factors related to individual health and quality of life are correlated with lifestyle [33]. Its modification should be a key measure in preventing this complication, rather than abandoning effective ISO therapy [34]. Changing lifestyle habits can be also useful in treating symptoms of dry mucous membranes. It is known that avoiding caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and dry or hard-to-chew foods can reduce the unpleasant sensations associated with dryness [35].

4.6. Limitations

In our analysis, an important limitation was the study design. Collecting results online prevents the possibility of explaining ambiguities to the patient, and respondents with biases may select themselves into the sample. Furthermore, only patients who spoke Polish were included. The outcomes may also have been significantly affected by the small population. Hence, the results obtained may not correspond to the results if the cohort had been larger. Additionally, our study does not allow analysis of the gender effect on ISO side effects due to the significantly lower response of men to the questionnaire compared to the female population. That also limited the ability to analyze the difference in the effect of sex hormones related to acne on ISO AEs. In addition, a limitation is the lack of control for other medications taken by patients, which may have influenced AEs or targeted potential patient diseases that could have distorted the results. Due to the retrospective nature of the study design, it was impossible to establish a temporal relationship between exposure and outcome. Therefore, no dose-effect analysis was performed. As for assessing nutritional status, it is worth mentioning that BMI as an indicator is an unreliable tool.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that the Mediterranean diet, BMI, physical activity, and smoking do not affect the incidence and severity of ISO treatment-related AEs, demonstrating the safety of ISO therapy regardless of unhealthy habits. Given that they may alter the severity of acne through their involvement in pathogenesis, the general recommendations for adherence should not be disregarded. The most severe or unique AEs were rare and likely represent individual drug responses. In conclusion, ISO is still an effective medication for acne vulgaris, and despite the side effects, it should not be abandoned regardless of personal healthy and unhealthy habits.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

J.L., J.K., W.P., and A.O.S. conceptualized the study; J.L. and J.K. provided the methodology; J.K handled software; J.L. and J.K. validated the study; J.L. and J.K. performed formal analysis; J.L. and J.K. investigated the study; J.L. and J.K. collected resources; J.L. and J.K. curated the data; J.L. and J.K. wrote the original draft; W.P. and A.O.S. wrote, reviewed, and edited the study; J.L. and J.K. visualized the study; W.P. and A.O.S. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript. Julia Lewandowska and Jan Kapała should be considered joint first authors. Julia Lewandowska is the submitting author, and her institutional e-mail address is [email protected].

Open Research

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions and are available from the corresponding author upon request.