Attitudes toward Cancer Diagnosis Disclosure and Resilience among Suspicious Lung Cancer Patients, Lung Cancer Patients, and Their Families

Abstract

Objective. This study aimed to compare the attitudes and preferences on cancer diagnosis disclosure (CDD) among suspicious lung cancer patients (SLCPs), lung cancer patients (LCPs), and their family members and to explore their associations with resilience. Methods. A cross-sectional study was conducted at Yunnan Cancer Hospital in China, from March to August 2022. A total of 1016 participants including 254 SLCP-family pairs and 254 LCP-family pairs completed self-administered questionnaires to assess their attitudes toward CDD and resilience. Continuous variables were expressed by means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented by numbers and percentages. The comparisons between groups were tested by using a t-test or chi-squared test. Associations between resilience and CDD attitudes in the four groups were estimated by multivariate logistic regression models. Results. Compared with LCPs, more SLCPs believed that patients should be informed of their cancer diagnoses (63.8% vs 43.7%, p < 0.001), and the distribution of the first one to know the diagnosis was disequilibrium (p < 0.05). The significant difference was identified in participants’ attitudes toward patients being told the facts by resilience levels among the different groups. Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that resilience was associated with participants’ preference for patients being informed of their cancer diagnoses in the SLCPs group (adjusted OR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.25), LCPs group (adjusted OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.32–3.74), and family of LCPs group (adjusted OR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.04–3.12). We further performed a sensitivity analysis using quantiles of resilience. Conclusion. SLCPs and LCPs exhibited different attitudes towards CDD. Resilience plays a positive role in CDD. Our study suggests that healthcare practitioners should consider patients’ diagnosis state when disclosing a cancer diagnosis and tailor their disclosure methods based on the patients’ and families’ preferences and resilience. Our findings provide important implications to guide future research and intervention programs to improve cancer diagnosis disclosure for SLCPs, LCPs, and their families.

1. Introduction

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, accounting for one-fifth of all cancer deaths [1]. China has the highest burden of lung cancer, with approximately 815,563 new diagnoses of lung cancer in 2020 [2, 3] and a projected increase in mortality of 40% by 2030 [4]. Being diagnosed with lung cancer has been shown to cause significant emotional stress, depression, fatigue, and sleep disorders for patients and their families [5].

Cancer diagnosis disclosure (CDD) is the most stressful and difficult job for health care providers, especially for Chinese doctors [6, 7]. In Western countries, CDD is common and acceptable with an emphasis on patient autonomy [8–11]. Approximately 98% of physicians disclosed the diagnosis directly to patients in the USA [12]. In China, it is stated by law that medical personnel should take legal responsibility if disclosing a diagnosis produces ill effects on patients [13]. Meanwhile, Chinese culture is dominated by the Confucian tradition of “familial responsibility,” which prioritizes “family consent for disclosure” for illnesses with unfavorable prognoses such as cancer [14, 15]. As a result, many Chinese doctors chose not to inform patients of their cancer diagnoses, as requested by their families. In China, an estimated 35.8%–50.3% of cancer patients have been reported to have their cancer diagnoses withheld by doctors in various studies [16–18]. A study in Beijing revealed that 75% of oncologists believed patients do want to be told bad news first, but most oncologists (78%) still chose to deliver the cancer diagnosis to the family first [19].

Meanwhile, an increasing number of cancer patients in China prefer to know their cancer diagnosis, and the practice of nondisclosure of cancer diagnosis has been gradually recognized as not respecting patients’ rights and autonomy [18, 20]. Studies have shown that 90.8% of cancer patients wanted to be told the facts if they got cancer at an early stage, compared with 69.9% of families. Similarly, the preference for delivering a terminal diagnosis was significantly higher in patients (60.5%) compared to families (34.4%) [21]. However, most of the previous studies were focused on cancer survivors with confirmed cancer diagnoses, while much less attention was paid to suspicious cancer patients (SCPs). SCPs know that they are highly likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer, who are in a key transitional stage from noncancer to possible cancer diagnosis, and their attitudes towards CDD are essential to guide health providers’ decision-making in whether and how to deliver a cancer diagnosis. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the attitudes toward CDD of SCPs and their families to provide recommendations for health providers. To date, no studies have examined the attitudes about cancer disclosure among SCPs and their families.

Although CDD is a stressful process that may lead to long-term psychological distress such as depression and anxiety, as well as behavioral problems among both patients [11, 13, 22] and their families [23–25], not everyone displays the same level of mental health problems. Among various factors that may affect patients’ and families’ responses to CCD, psychological resilience has been identified as the most important one. Psychological resilience is defined as an individual’s ability to recover or rebound from distress, depression, or anxiety feelings so that the individual can reach a stable and healthy state when facing a threatened event [26]. Previous studies have illustrated that resilience in cancer patients is a unique and dynamic process to cope with adversity and responses to cancer [27] and may help relieve emotional harm and improve the quality of life in cancer patients and their families [23]. However, no study has explored the association between resilience and CCD attitudes so far.

Therefore, we conducted the current study to compare the attitudes and preferences toward CDD among suspicious lung cancer patients (SLCPs), lung cancer patients (LCPs), and their family members, as well as to explore their associations with resilience. Our findings would provide important guidance for the development of training and intervention programs to improve the CDD of lung cancer patients.

2. Method

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Yunnan Cancer Hospital, which was the Cancer Center of Yunnan Province, China. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit a total of 1016 participants (254 pairs of SLCPs and families and 254 pairs of LCPs and their families) consecutively from March 2022 to August 2022. Whenever one participant from SLCPs or LCPs was selected, one of their families (spouse, parents, son, or daughter) also correspondently was selected for survey. LCPs and their families had known the patients’ lung cancer diagnoses, which generally families of patients were informed first, and patients were informed within a week, while SLCPs and their families did not know the patients’ diagnoses yet.

The inclusion criteria for SLCPs included (1) visiting a lung cancer outpatient department without a confirmed cancer diagnosis; (2) living with family; (3) aged 18 or older; (4) willing to sign the informed consent. The exclusion criteria included (1) cannot finish the questionnaire due to a serious physical or mental illness. The inclusion criteria of the SLCPs’ families included (1) identified by SLCPs as the primary caregivers playing the most important role in SLCPs’ therapy decisions and care; (2) aged 18 or older; and (3) willingness to sign informed consent. The exclusion criteria included: (1) cannot finish the questionnaire due to a serious physical or mental illness.

The inclusion criteria of LCPs included (1) having a confirmed and primary lung cancer diagnosis; (2) being informed of their lung cancer diagnosis; (3) living with family; (4) aged 18 or older; and (5) willingness to sign informed consent. The exclusion criteria included (1) cannot finish the questionnaire due to serious physical or mental illness. Inclusion criteria of the LCPs’ family included (1) identified by LCPs as the primary caregivers playing the most important role in LCPs’ therapy decisions and care; (2) being informed of the patient’s lung cancer diagnosis; (3) aged 18 or older; and (4) willingness to sign informed consent. Families who cannot finish the questionnaire due to serious physical or mental illness were excluded.

2.2. Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Yunnan Cancer Hospital (KY202004). Participants were approached and recruited from the outpatient and inpatient departments of thoracic surgery by well-trained nurse investigators who have been working in the departments and have known the patients well. Investigators explained the research purpose and procedure clearly to eligible participants. Participants were fully informed that they could withdraw from this survey at any time, and their choice to participate in or refuse the study will not affect their rights to receive medical services. The researchers guaranteed that all data were collected anonymously, kept confidential, and used for research purposes only. After providing written informed consent, the patients and their families were invited to finish a battery of questionnaires independently in separate rooms so that they didn’t influence each other’s answers. At the end of the survey, the investigators checked the questionnaires to ensure the integrity of the information and that there was no missing data. A total of 1016 questionnaires (254 pairs of SLCPs and families and 254 pairs of LCPs and their families) were distributed, and all of them were effectively retrieved. In Chinese culture, cancer is still a sensitive topic, and it is considered unlucky and bad manners to talk about one’s cancer or assume someone has cancer, especially for SLCPs. Therefore, we used “if a patient got cancer” instead of “if you got cancer” for the questions about cancer disclosure.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Demographic Information

The sociodemographic characteristics of SLCP-family and LCP-family pairs were collected by a self-designed information sheet, which included the relationship between patient and family, sex, age, minority, religion, and other relevant information.

2.3.2. Attitudes of CDD

Both the patient’s and family’s current attitudes toward CDD were assessed by two questions asking whether a patient with a lung cancer diagnosis should be told the fact (optional answers: yes/no) and who should be the first person to notify (optional answers: patient/family/patient and family).

2.3.3. Psychological Resilience

Considering a short questionnaire can improve cooperation of participants, psychological resilience was assessed by the Chinese version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) [28]. The CD-RISC-10 reflects one’s resilience to tolerate negative life events, such as personal problems, illness, pressure, and failure. The 10 items of the CD-RISC-10 were simplified from the original 25 items of the CD-RISC, and each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 = “never” to 4 = “almost always.” The total score ranges from 0 to 40, with a higher score indicating a higher level of resilience. Based on a median value cutoff, participants were further classified into low- and high-resilience groups. The Chinese version of CD-RISC-10 has shown good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.851–0.910). In the current study, the CD-RISC-10 showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α of 0.94.

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

R language (R 4.1.2, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software was used for all data analyses. Continuous variables were expressed by means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented by numbers and percentages. Group differences for continuous variables were tested using independent t-tests for two groups. Group differences for categorical variables were tested using chi-squared tests. The associations between resilience and CDD attitudes among various groups were estimated by the multivariate logistic regression model. A two-tailed probability less than 0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

This study recruited 1016 participants including 254 SLCP-family pairs and 254 LCP-family pairs between March 2022 and August 2022. The majority of participants were married, were of Han ethnicity, and lived in urban areas. For participants from the LCPs group, 213 (83.86%) were in the early stages. The median combined score of resilience ranged from 27.00 to 30.00 across the different groups. Detailed characteristics relating to the surveyed subject are summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | SLCPs group | Family of SLCPs group | LCPs group | Family of LCPs group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 254 | N = 254 | N = 254 | N = 254 | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 51.89 (13.06) | 40.54 (12.17) | 53.82 (9.70) | 41.16 (12.66) |

| Gender (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 120 (47.2) | 131 (51.6) | 91 (35.8) | 140 (55.1) |

| Female | 134 (52.8) | 123 (48.4) | 163 (64.2) | 114 (44.9) |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| Early stage (I-II stage) | — | — | 213 (83.86) | — |

| Advanced stage (III-IV stage) | — | — | 41 (16.14) | — |

| Marriage status (n, %) | ||||

| Not married | 28 (11.0) | 48 (18.9) | 22 (8.7) | 44 (17.3) |

| Married | 226 (89.0) | 206 (81.1) | 232 (91.3) | 210 (82.7) |

| Education level (n, %) | ||||

| Middle school and below | 149 (58.7) | 85 (33.5) | 133 (52.4) | 77 (30.3) |

| High school and above | 105 (41.3) | 169 (66.5) | 121 (47.6) | 177 (69.7) |

| Residence (n, %) | ||||

| Rural | 134 (52.8) | 120 (47.2) | 125 (49.2) | 116 (45.7) |

| Urban | 120 (47.2) | 134 (52.8) | 129 (50.8) | 138 (54.3) |

| Month income (n, %) | ||||

| 3000–3999 and below | 165 (65.0) | 126 (49.6) | 174 (68.5) | 156 (61.4) |

| 4000–4999 and above | 89 (35.0) | 128 (50.4) | 80 (31.5) | 98 (38.6) |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | ||||

| Han | 180 (70.9) | 174 (68.5) | 218 (85.8) | 225 (88.6) |

| Ethnic minority | 74 (29.1) | 80 (31.5) | 36 (14.2) | 29 (11.4) |

| Belief (n, %) | ||||

| No | 204 (80.3) | 206 (81.1) | 244 (96.1) | 247 (97.2) |

| Yes | 50 (19.7) | 48 (18.9) | 10 (3.9) | 7 (2.8) |

| Resilience (median, range) | 28.0 (4, 40) | 30.00 (12, 40) | 27.0 (0, 40) | 27.0 (0, 40) |

3.2. Attitudes towards CDD and Resilience

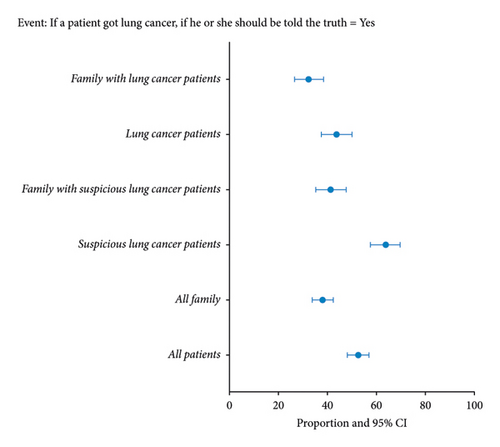

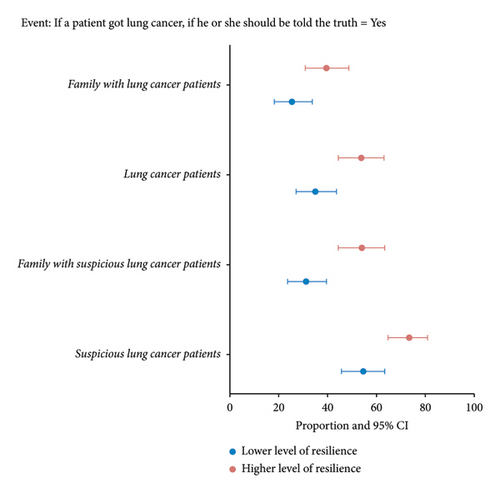

Table 2 shows the comparison of attitudes towards CDD between the SLCP group and the LCP group. Compared with LCPs, more SLCPs believed that patients should be told of their cancer diagnoses (63.8% vs 43.7%, p < 0.001), and the distribution of the first one to know the diagnosis was disequilibrium (p < 0.05). Figure 1(a) further shows a comparison of participants’ attitudes toward patients being informed of their cancer diagnoses among the SLCP group, LCP group, SLCP family group, and LCP family group. In general, patients were more likely to think that patients should be told the facts about their cancer diagnoses than their families. The significant difference was identified in participants’ attitudes toward patients being told the facts by resilience levels among the SLCP group (p < 0.001), LCP group (p = 0.003), SLCP family group (p < 0.001), and LCP family group (p < 0.02). In general, participants with higher resilience were more likely to think that patients should be told the facts about their cancer diagnoses than those with lower resilience (Figure 1(b)).

| Variable | SLCP group | LCP group | p value | SLCP family group | LCP family group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Whether a patient with lung cancer diagnosis should be told the truth? (n, %) | ||||||

| Yes | 162 (63.8) | 111 (43.7) | <0.001 | 105 (41.3) | 82 (32.3) | 0.043 |

| No | 92 (36.2) | 143 (56.3) | 149 (58.7) | 172 (67.7) | ||

| Q2 Who should be the first person to notify a cancer diagnosis? (n, %) | ||||||

| Patient | 52 (20.5) | 22 (8.7) | <0.001 | 10 (3.9) | 7 (2.8) | 0.014 |

| Patient and family | 125 (49.2) | 103 (40.6) | 103 (40.6) | 74 (29.1) | ||

| Family | 77 (30.3) | 129 (50.8) | 141 (55.5) | 173 (68.1) | ||

3.3. Influencing Factors of CDD Attitudes

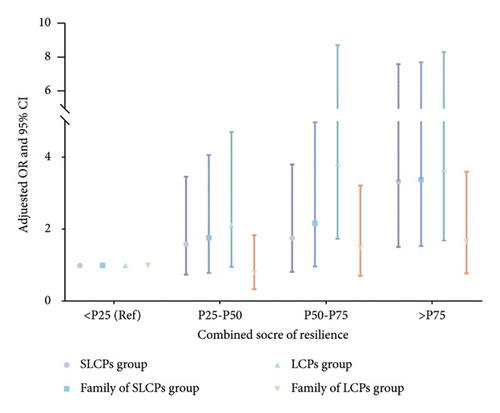

We conducted a series of multivariate logistic regression analyses to explore the influencing factors of CDD attitudes among the SLCP group, LCP group, SLCP family group, and LCP family group, respectively. In each model, the dependent variable was whether participants believed that patients should be informed of their cancer diagnoses, while the independent variables were the social demographic characteristics that were significant in each univariate analysis. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, resilience was associated with participants’ preference for patients being informed of their cancer diagnoses in the SLCPs group (adjusted OR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.08–3.25), LCPs group (adjusted OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.32–3.74), and family of LCPs group (adjusted OR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.04–3.12). For participants who were from these groups, a higher level of resilience was associated with an increase in odds of cancer diagnosis disclosure by at least 79%.

| Variables | Event: CDD preference = yes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLCPs group | p value | LCPs group | ||||||

| Univariate | p value | Multivariate | Univariate | p value | Multivariate | p value | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Age (+5 years) | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.538 | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 0.763 | ||||

| Gender: (ref: male) | ||||||||

| Female | 0.84 (0.51–1.41) | 0.519 | 1.21 (0.72–2.04) | 0.466 | ||||

| Marriage status (ref: not married) | ||||||||

| Married | 1.16 (0.52–2.59) | 0.721 | 0.51 (0.21–1.23) | 0.134 | ||||

| Education level (ref: middle school and below) | ||||||||

| High school and above | 1.78 (1.04–3.04) | 0.034 | 1.55 (0.81–2.95) | 0.184 | 0.89 (0.54–1.46) | 0.634 | 0.72 (0.38–1.32) | 0.291 |

| Residence (ref: rural) | ||||||||

| Urban | 1.80 (1.07–3.03) | 0.028 | 1.09 (0.57–2.07) | 0.795 | 1.26 (0.77–2.07) | 0.359 | 1.47 (0.80–2.73) | 0.221 |

| Month income (ref: 3000–3999 and below) | ||||||||

| 4000–4999 and above | 1.10 (0.64–1.88) | 0.735 | 0.93 (0.55–1.59) | 0.794 | ||||

| Ethnicity (ref: han) | ||||||||

| Ethnic minority | 0.35 (0.20–0.60) | 0.001 | 0.54 (0.25–1.13) | 0.1 | 1.53 (0.75–3.11) | 0.238 | 2.12 (0.98–4.71) | 0.058 |

| Belief (ref: no) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.29 (0.15–0.55) | 0.001 | 0.54 (0.23–1.28) | 0.162 | 0.31 (0.06–1.49) | 0.143 | 0.21 (0.02–1.00) | 0.075 |

| Resilience (ref: combined score < median) | 2.29 (1.35–3.88) | 0.002 | 1.87 (1.08–3.25) | 0.025 | 2.16 (1.31–3.59) | 0.003 | 2.21 (1.32–3.74) | 0.003 |

| Variable | Event: CDD preference = yes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family of SLCPs group | p value | Family of LCPs group | ||||||

| Univariate | p value | Multivariate | Univariate | p value | Multivariate | p value | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Age (+5 years) | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) | 0.001 | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.025 | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 0.341 | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.025 |

| Relationship to patient: (ref: other relatives) | ||||||||

| Spouse | 1.59 (0.60–4.24) | 0.35 | 0.83 (0.21–3.25) | 0.786 | ||||

| Child | 0.67 (0.25–1.79) | 0.426 | 0.45 (0.11–1.79) | 0.257 | ||||

| Gender: (ref: male) | ||||||||

| Female | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | 0.209 | 1.44 (0.83–2.49) | 0.192 | ||||

| Marriage status (ref: not married) | ||||||||

| Married | 1.75 (0.84–3.65) | 0.136 | 1.31 (0.63–2.72) | 0.471 | ||||

| Education level (ref: middle school and below) | ||||||||

| High school and above | 1.55 (0.87–2.74) | 0.134 | 0.86 (0.48–1.54) | 0.618 | ||||

| Residence (ref: rural) | ||||||||

| Urban | 3.15 (1.81–5.50) | 0.001 | 2.04 (1.04–4.02) | 0.039 | 1.48 (0.85–2.58) | 0.164 | 1.53 (0.83–2.84) | 0.175 |

| Month income (ref: 3000–3999 and below) | ||||||||

| 4000–4999 and above | 2.13 (1.24–3.65) | 0.006 | 1.28 (0.69–2.40) | 0.435 | 1.17 (0.67–2.04) | 0.571 | 0.87 (0.47–1.60) | 0.652 |

| Ethnicity (ref: han) | ||||||||

| Ethnic minority | 0.70 (0.39–1.24) | 0.22 | 1.49 (0.63–3.53) | 0.363 | ||||

| Belief (ref: no) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.43 (0.21–0.88) | 0.02 | 0.72 (0.32–1.64) | 0.437 | 0.32 (0.04–2.75) | 0.302 | 0.38 (0.02–2.35) | 0.376 |

| Resilience (ref: combined score < median) | 2.56 (1.49–4.42) | 0.001 | 1.76 (0.96–3.21) | 0.066 | 1.86 (1.07–3.24) | 0.027 | 1.79 (1.04–3.12) | 0.036 |

We further performed a sensitivity analysis using quantiles of resilience, which revealed that the odds of preferring to disclose a cancer diagnosis increased with an escalated level of resilience, but the trend for dose-response association was weak (Figure 1(c)).

4. Discussion

4.1. Attitudes toward “Whether a Patient with a Lung Cancer Diagnosis Should Be Told the Fact” among SLCP, LCP, and Their Families

Our study revealed that patients were more likely to believe that patients should be told their cancer diagnoses than their families. This finding is consistent with the various studies showing that most cancer patients wanted to know their diagnoses in various countries and reflects a general trend toward patient autonomy worldwide [29, 30]. The discordance between patients and their families might have originated from Chinese Confucianism and the beneficence principle [20]. Confucianism, one of the most influential philosophies in the history of China, emphasizes familial responsibility and harmony, as an important reason for nondisclosure [31]. On the other hand, the beneficence principle refers to actions done for the benefit of others and is closely associated with mercy and kindness, which lead families to tend to protect patients. Therefore, families perceive nondisclosure as nonmaleficence for the patients being treated as a vulnerable group.

However, attitudes toward CDD varied by the cancer diagnosis state in both patients and families. SLCPs were more willing to be told about a cancer diagnosis than LCPs. A similar tendency was observed in the families with the SLCP families being more willing to inform patients about their cancer diagnoses than the LCP families.

One possible explanation may be that patients with a confirmed cancer diagnosis may experience significant mental harm after being informed of the diagnosis, leading to deteriorating physical status. Previous studies demonstrated that knowing a lung cancer diagnosis brings a high level of emotional problems and a detrimental relevant score of quality of life (QoL) to patients and their families simultaneously [5, 32–34], potentially leading to a shorter survival period [5]. As a result, LCP patients and their families may believe that concealing a cancer diagnosis is an effort to protect patients from the psychological burden of knowing. What is noticeable is that, during the clinical practice, the individuals to whom the first-time oncologist discloses the lung cancer diagnosis are SLCPs and their families. Therefore, the attitudes towards CDD between SLCPs and their families should be respected and considered more by health providers. Another implication of these findings is that the discrepancy in attitudes toward CDD between SLCPs families and LCPs families should be highlighted for further research to clarify the influencing factors of this discordance and the changed trajectory of attitudes. Moreover, future coping strategy, mental intervention, and communication training should be implemented to decrease the negative associations with CDD, facilitating full and effective CDD which is the precondition for high-quality medical decisions [14].

4.2. Attitudes toward “Who Should Be the First Person to Notify” among SLCP, LCP, and Their Families

Regarding who should be the first to know a lung cancer diagnosis, our study showed that both SLCPs and their families were more willing to have patients and families informed together, while the LCPs and their families were more willing to have their families informed first. Obviously, regardless of the group, families are permanent candidates to be informed of patients’ cancer diagnosis. The possible explanation would be that Confucian tradition is the most predominant sociocultural factor in the Chinese medical setting, emphasizing familial autonomy and family harmony. Previous studies have identified the different attitudes toward CDD between patients with a confirmed cancer diagnosis and their family members [35]. Our study further adds more information on the various attitudes toward CDD among patients with suspected cancer diagnosis. When a health provider tells patients’ diagnosis initially, they usually face suspicious cancer patients and their families, so the preference of SLCPs and their families should be given priority when telling the cancer diagnosis to patients and their families simultaneously. Furthermore, the attitude of LCPs and their families implies that the family would be the appropriate first person to notify during the later disclosure such as the prognosis, treatment effects, and life expectancy. Our study showed that there were different preferences on CDD between patients with suspicious lung cancer and confirmed lung cancer diagnosis, further highlighting the importance of our study. It is suggested that CDD for lung cancer should distinguish between SLCP and LCP and balance the needs of both patients and their families.

4.3. Association between Resilience and CDD Attitudes

In China, family involvement in CDD also reflects that the family plays an important role in clinical decision-making to protect patients from the psychological burden of truth-telling [14]. Previous studies have identified various psychological factors associated with cancer patients’ truth-telling preference, such as distress, anxiety, and fighting spirit [36]. To our best knowledge, our study is the first to examine the association between resilience and CDD attitudes. Our study found that patients and families with higher levels of resilience were more willing to have patients be told their true cancer diagnoses, regardless of their diagnosis status. Although receiving a cancer diagnosis may cause tremendous stress for most people, not everyone copes with this challenge in the same way. Previous studies have shown resilience as a crucial protective factor to help people cope with distress and adapt to challenging events, such as the diagnosis of a life-threatening disease [37]. People with higher levels of resilience hold more optimistic life attitudes and are more accepting of bad news such as a cancer diagnosis [38]. What is noteworthy is that resilience was an independently influential factor in CDD attitudes for SLCP by multivariate analysis. Therefore, before disclosing a cancer diagnosis, resilience assessment and training are highly warranted as a complement to promote better CDD, especially among SLCPs.

Compared with normal adults and Chinese military personnel, SLCPs, LCPs, and their families show lower resilience scores [39]. Nevertheless, previous studies reveal the resilience of SLCPs and LCPs is both higher than that of colorectal and breast cancer patients [40, 41], while SLCPs’ and LCPs’ families have worse resilience than other cancer caregivers [42]. Considering these findings, we suggest that resilience among SLCPs, LCPs, and their families should be concerned and improved, particularly to the families, so as to promote CDD efficiently. It has been noted that resilience is a dynamic process [43] and changes accordingly based on experiences and learning [44, 45]. Our study showed that both LCPs and their families had lower resilience scores than SLCPs and their families. This result highlights the possibility of a resilience shift based on the changeable state of cancer diagnosis but needs to be tested in a future longitudinal study. The findings of this study suggest that more assessments and interventions should be developed to enhance resilience and promote CDD.

5. Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, all participants were recruited from one hospital, which may limit the sample representativeness and the generalization of our findings. Future multicenter studies with a more representative and diverse sample are needed. Second, we cannot infer any causal relationship between resilience and CCD attitudes due to the cross-sectional study design, which needs to be established by future longitudinal studies. Third, the assessment of attitudes toward CDD was based on two simple self-designed questions instead of standard questionnaires, making it hard to compare our results with other studies using different assessment tools. Future studies should consider using more validated assessment tools to facilitate cross-study comparisons. Fourth, a paired selection of participants may underestimate the difference between patients and their families in CCD attitudes since people living in the same family tend to have shared attitudes and beliefs. Despite all this, the current study still identified significant differences in CCD attitudes across varied groups. For future studies, it could be worth investigating CCD attitudes and resilience in patients who do not live with families.

6. Conclusion

Our study on attitudes toward CDD among a sample of Chinese LCPs, SLCPs, and their families showed that CDD attitudes varied by cancer diagnosis status. SLCPs and their families were more willing to let the patients be told the facts than LCPs and their families. SLCPs and their families preferred to be informed of a cancer diagnosis together, while LCPs and their families preferred to be informed first. Both SLCPs and their families showed higher levels of resilience than LCPs and their families. Higher resilience was associated with a higher preference for patients being told of their cancer diagnoses. Our study suggests that health practitioners should consider patients’ diagnosis state when disclosing a cancer diagnosis and tailor their disclosure methods based on the patients’ and families’ preferences and resilience. Our findings provide important implications to guide future research and intervention programs to improve cancer diagnosis disclosure for SLCPs, LCPs, and their families.

Disclosure

Qiongyao Guan and Hailiang Ran are co-first authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Qiongyao Guan and Hailiang Ran contributed equally to this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating patients, family members, and medical staff, and they are grateful to Mayur M Desai of Yale School of Public Health, Yuanyuan Xiao from the School of Public Health, Kunming Medical University for guiding this study. This work was funded by Yunnan Applied Basic Research Projects-Kunming Medical University Union Foundation (Grant Number: 202101AY070001-178, 202201AY070001-156).

Open Research

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available by contacting author Jiao Yang upon reasonable request.