Analysis of the Phenotypes in the Rett Networked Database

Abstract

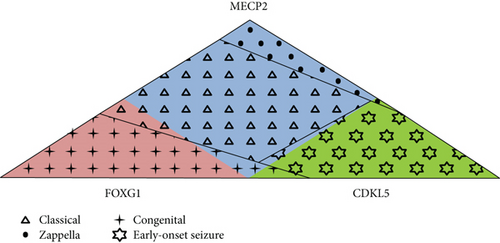

Rett spectrum disorder is a progressive neurological disease and the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability in females. MECP2 is the major causative gene. In addition, CDKL5 and FOXG1 mutations have been reported in Rett patients, especially with the atypical presentation. Each gene and different mutations within each gene contribute to variability in clinical presentation, and several groups worldwide performed genotype-phenotype correlation studies using cohorts of patients with classic and atypical forms of Rett spectrum disorder. The Rett Networked Database is a unified registry of clinical and molecular data of Rett patients, and it is currently one of the largest Rett registries worldwide with several hundred records provided by Rett expert clinicians from 13 countries. Collected data revealed that the majority of MECP2-mutated patients present with the classic form, the majority of CDKL5-mutated patients with the early-onset seizure variant, and the majority of FOXG1-mutated patients with the congenital form. A computation of severity scores further revealed significant differences between groups of patients and correlation with mutation types. The highly detailed phenotypic information contained in the Rett Networked Database allows the grouping of patients presenting specific clinical and genetic characteristics for studies by the Rett community and beyond. These data will also serve for the development of clinical trials involving homogeneous groups of patients.

1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT, OMIM 312750) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder that affects predominantly females with an incidence of approximately 1 in 10,000 female births mainly caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene located in the X chromosome [1, 2]. Classic RTT is infrequently observed in males because a deleterious mutation in the only copy of MECP2 typically results in severe neonatal encephalopathy and early lethality [3]. In the classic form, girls with RTT typically exhibit a relatively normal period of development for the first 6-18 months of life followed by a regression phase where patients lose acquired language and motor skills and exhibit intellectual disability and hand stereotypies. The hand stereotypies are typical in RTT and appear commonly to be continuous, located predominantly over the anterior body midline [4].

Beyond the classic form of RTT, a number of atypical forms with different degrees of severity have been described: the Zappella variant (formerly known as the preserved speech variant) [5, 6], the infantile seizure onset type [7], the congenital form [8], and the “forme fruste” [9]. Besides the MECP2 gene, additional genes have been associated with the RTT phenotype. In particular, mutations in CDKL5, located on the X chromosome, have been reported in the infantile seizure onset type of RTT, while mutations in FOXG1, located on chromosome 14, have been reported in patients with the congenital presentation. It is still an object of debate if CDKL5 and FOXG1 mutations are responsible for atypical RTT or for a different neurodevelopmental phenotype [10–12].

Different RTT databases have been generated in the past and recent years. Among them are the International Rett Syndrome Association (IRSA) North American database and the InterRett [13, 14]. The Rett Networked Database (RND) is a registry of clinical and molecular data for patients affected by RTT and available at https://www.rettdatabasenetwork.org [15]. Although it was initially targeting the European population of patients with RTT, it is now open to countries outside of Europe. RND records are updated by clinicians with experience in RTT, limiting potential bias existing when clinical data are gathered using questionnaires sent out to families by mail. It is among the largest RTT registries worldwide with more than 1900 patients on file, and it is designed to be an open-access initiative since data can be retrieved directly through a web-based search engine by interested professionals upon the submission of a research proposal to the Scientific Review Board [15]. The public has access to general information and to content description while the individual patient file can be granted only upon registration of physicians and clinical researchers in charge of specific patients.

Here, we describe the first 1007 records contained in the registry and discuss the content of RND on the basis of the published guidelines for RTT clinical diagnosis [16, 17]. We analyzed the phenotype of patients with a MECP2, CDKL5, or FOXG1 mutation to better understand the typical and atypical forms of RTT and provide information of RTT cohorts for the development of clinical trials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. RND Data

RND contains clinical files for 1958 patients affected by classic or atypical RTT (numbers are given as of March 1, 2017). Clinical data originates from Croatia (29 patients), Denmark (64 patients), France (252 patients), Hungary (82 patients), India (3 patients), Israel (93 patients), Italy (605 patients), Romania (15 patients), Serbia (50 patients), Spain (398 patients), United Kingdom (255 patients), USA (96 patients), and Russia (16 patients).

Patient clinical and genetic data were provided and inserted by the expert clinician through direct patients’ evaluation, as described in Grillo et al. [15]. The system is able to collect 309 items (293 clinical and 16 genetic) grouped into 31 domains (30 clinical and 1 genetic). The system is permissive since patients with incomplete data can be inserted and later updated.

Data analysis is presented for the first 1007 patients aged over 5 years and for whom a pathogenic mutation in MECP2, FOXG1, or CDKL5 has been identified. Enrolled patients either met the diagnostic criteria for RTT or had a mutation in MECP2. All participants had complete mutation testing including MECP2 sequencing and deletion/duplication testing. Clinical diagnosis utilized the 2002 consensus criteria [12] or the revised diagnostic criteria for RTT published in 2010 [11]. CDKL5- and FOXG1-mutated patients were included whenever the diagnosis of RTT was achieved according to the 2002 consensus criteria or 2010 revised RTT criteria.

2.2. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the RND dataset. MECP2 mutation types were grouped as Arg106Trp, Arg133Cys, Thr158Met, Arg306Cys, Arg168 ∗, Arg255 ∗, Arg270 ∗, Arg294 ∗, C-terminal deletion, early truncating mutations (mutations interrupting the MECP2 protein before amino acid 310), and large deletions. Those not falling in any of the above listed categories were grouped as “other.” CDKL5 mutation types were clustered on the basis of early truncating mutations, late truncating mutations, large deletions, and missense mutations. FOXG1 mutation types were grouped as early truncating mutations, late truncating mutations, gene deletions, and missense mutations.

Differences in clinical characteristics between groups of patients were tested by Fisher’s exact test or by chi-squared analysis when the normal approximation was appropriate. R tool version 3.5.1 was used for statistical analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of RND Data

Among the 1007 RTT patients analyzed in this study, 806 were classified as classic, while the remaining 201 as atypical. Among this latter group, 46 had the congenital form of RTT, 36 patients the early-onset seizure variant, and 54 the Zappella variant (formerly known as the preserved speech variant). For the remaining 65 patients, the type of atypical form was not specified. All cases were sporadic except for 2 pairs of sisters and 5 pairs of monozygotic twins affected by RTT and carrying a MECP2 mutation.

MECP2 was mutated in 949 patients (94.2%), while 32 patients carried a mutation in CDKL5 (3.2%) and 26 patients in FOXG1 (2.6%).

3.2. Patients Carrying a Mutation in MECP2

Among the 949 MECP2-mutated patients, 804 have a diagnosis of classic RTT (84.7%), 24 the congenital variant (2.5%), five the early-onset seizure variant (0.5%), and 54 the Zappella variant (5.7%) and the remaining 62 have an atypical form of RTT not better specified in categories (6.5%). All mutation types are present in this population with p.Arg255 ∗, p.Thr158Met, and C-terminal deletions being the most frequent mutations despite significant difference between classic and atypical forms (Table 1).

| Mutation type | Total (%) (n = 949) |

Classic RTT N (%) (n = 804) |

Atypical RTT N (%) (n = 145) |

p value classic vs. atypical RTT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Arg106Trp | 31 (3.3) | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | 0.894 |

| p.Arg133Cys | 62 (6.5) | 37 (59.7) | 25 (40.3) | <0.0001 |

| p.Thr158Met | 102 (10.8) | 91 (89.2) | 11 (10.8) | 0.182 |

| p.Arg168 ∗ | 80 (8.4) | 74 (92.5) | 6 (7.5) | 0.043 |

| p.Arg255 ∗ | 106 (11.2) | 96 (90.6) | 10 (9.4) | 0.076 |

| p.Arg270 ∗ | 62 (6.5) | 57 (91.9) | 5 (8.1) | 0.102 |

| p.Arg294 ∗ | 63 (6.6) | 59 (93.7) | 4 (6.3) | 0.041 |

| p.Arg306Cys | 67 (7.1) | 58 (86.6) | 9 (13.4) | 0.663 |

| C-Terminal deletion | 101 (10.6) | 78 (77.2) | 23 (22.8) | 0.027 |

| Early truncating | 93 (9.8) | 80 (86) | 13 (14) | 0.713 |

| Large deletion | 72 (7.6) | 65 (90.3) | 7 (9.7) | 0.173 |

| Other | 110 (11.6) | 83 (75.4) | 27 (24.5) | 0.004 |

- N: number of cases for which the corresponding item is present; percentage is provided in brackets; the p value of significance is provided for comparison.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of RTT were last revised in the RTT Diagnostic Criteria 2010 [11] in order to include a regression period, partial or complete loss of acquired purposeful hand skills, stereotypic hand movements, partial or complete loss of acquired spoken language, and gait abnormalities. We mined the RND data in order to investigate their compliance with the revised diagnostic criteria. Our analysis showed that, among the patients carrying a mutation in MECP2, regression occurred in 96.2% of patients, 86.5% lost or never acquired purposeful hand skills, 68.0% lost most or all spoken language, 68.1% had stereotypic hand movements, and 44.5% had gait dyspraxia (Table 2). On the other hand, the intense eye pointing phenotype of RTT patients is present in 87.6% of MECP2-positive cases (Table 2), although not included in the necessary criteria. In our dataset, the supporting criteria are present in about half of the patients carrying a mutation in MECP2 (Table 2).

| Clinical sign | N | N+ (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A period of regression | 743 | 715 (96.2) |

| Necessary criteria | ||

| Partial or complete loss of acquired purposeful hand skills | 743 | 673 (86.5) |

| Stereotypic hand movements | 880 | 599 (68.1) |

| Partial or complete loss of acquired spoken language | 754 | 513 (68.0) |

| Gait abnormalities | 821 | 365 (44.5) |

| Supportive criteria | ||

| Breathing disturbances when awake | 824 | 441 (53.5) |

| Bruxism when awake | 829 | 515 (62.1) |

| Impaired sleep pattern | 926 | 419 (45.2) |

| Abnormal muscle tone | — | — |

| Peripheral vasomotor disturbances | — | — |

| Scoliosis or kyphosis | 853 | 444 (52.1) |

| Growth retardation ∗ | 771 | 419 (54.3) |

| Small cold hands and feet | 160 | 81 (50.6) |

| Inappropriate laughing or screaming spells | 560 | 171 (30.5) |

| Diminished response to pain | — | — |

| Eye pointing | 958 | 843 (88.0) |

- N represents the number of cases for which the corresponding item is present in the patient file; N+ represents the number of cases positive for the clinical signs, and the percentage is provided in brackets. ∗Growth retardation was considered to be present when the weight was below the 25th percentile. When height is considered, 54.3% of MECP2-positive patients are below the 25th percentile.

RND data were further interrogated to define the most frequent clinical signs of MECP2 mutation carriers, among those retrieved in the RND (Table 3). This analysis revealed that, in addition to the necessary criteria for RTT diagnosis, a period of regression (96.2%), absence of speech (68.0%), a deficient sphincter control (88.5%), eye pointing (87.6%), feeding difficulties (85.2%), and a normal head circumference at birth (74.1%) are the main clinical signs in MECP2-mutated patients (Table 3).

| Clinical sign | MECP2 (N = 949) | CDKL5 (N = 32) | FOXG1 (N = 26) | p value MECP2 vs. CDKL5 | p value MECP2 vs. FOXG1 | p value CDKL5 vs. FOXG1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N+ (%) | N | N+ (%) | N | N+ (%) | ||||

| A period of regression | 743 | 715 (96.2) | 16 | 12 (75.0) | 25 | 13 (52.0) | <0.0001 | 0.140 | <0.0001 |

| Normal head circumference at birth | 769 | 570 (74.1) | 32 | 30 (93.8) | 17 | 14 (82.4) | 0.012 | 0.447 | 0.210 |

| Deficient sphincter control | 736 | 651 (88.5) | 25 | 24 (96.0) | 23 | 22 (95.7) | 0.241 | 0.283 | 0.952 |

| Eye pointing | 880 | 771 (87.6) | 32 | 13 (40.6) | 15 | 2 (13.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.052 |

| Feeding difficulties | 813 | 693 (85.2) | 38 | 37 (97.4) | 15 | 13 (86.7) | 0.0364 | 0.877 | 0.128 |

| Presence of hand stereotypies | 880 | 599 (68.1) | 28 | 24 (85.7) | 24 | 23 (95.8) | 0.048 | 0.004 | 0.217 |

| IQ < 40 | 704 | 477 (67.8) | 19 | 19 (100) | 24 | 24 (100) | 0.003 | 0.0008 | 1 |

| Microcephaly or deceleration of head growth | 771 | 419 (54.3) | 27 | 12 (44.4) | 26 | 26 (100) | 0.310 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Gait dyspraxia | 821 | 365 (44.5) | 27 | 20 (74.1) | 21 | 2 (9.5) | 0.002 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| No speech at examination | 754 | 513 (68.0) | 23 | 21 (91.3) | 24 | 24 (100) | 0.018 | 0.0009 | 0.140 |

| Epilepsy before 5 years of age | 548 | 345 (63.0) | 32 | 31 (96.9) | 16 | 14 (87.5) | 0.0001 | 0.044 | 0.206 |

| Scoliosis | 853 | 444 (52.1) | 24 | 2 (8.3) | 22 | 6 (27.3) | <0.0001 | 0.022 | 0.091 |

| Bruxism | 829 | 515 (62.1) | 32 | 14 (43.8) | 17 | 11 (64.7) | 0.036 | 0.828 | 0.163 |

| Height below the 25th percentile | 767 | 447 (58.3) | 27 | 13 (48.1) | 25 | 17 (68.0) | 0.295 | 0.332 | 0.148 |

| Cold extremities | 160 | 81 (50.6) | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 22 | 10 (45.5) | 0.553 | 0.649 | 0.692 |

| Weight below the 25th percentile | 771 | 419 (54.3) | 24 | 10 (41.7) | 25 | 17 (68.0) | 0.220 | 0.177 | 0.064 |

| Has never spoken | 754 | 445 (59.0) | 23 | 19 (82.6) | 26 | 24 (92.3) | 0.023 | 0.0007 | 0.301 |

| Gastrointestinal disturbances | 603 | 261 (43.3) | 26 | 10 (38.5) | 22 | 16 (72.7) | 0.627 | 0.006 | 0.018 |

| Breathing dysfunction | 824 | 441 (53.5) | 26 | 3 (11.5) | 25 | 7 (28.0) | <0.0001 | 0.012 | 0.139 |

| Troubled night time sleeping | 926 | 431 (46.6) | 32 | 14 (43.8) | 18 | 11 (61.1) | 0.756 | 0.220 | 0.239 |

| Never learned to walk | 821 | 230 (28.0) | 27 | 20 (74.1) | 23 | 21 (91.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.114 |

| Epilepsy not controlled by therapy | 548 | 117 (21.4) | 25 | 21 (84.0) | 17 | 10 (58.8) | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.069 |

| Never learned to sit | 664 | 51 (7.7) | 26 | 6 (23.1) | 23 | 18 (78.3) | 0.005 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Epilepsy before 1 year of age | 689 | 27 (3.9) | 32 | 31 (96.9) | 16 | 6 (37.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

- N represents the number of cases for which the corresponding item is present in the patient file; N+ represents the number of cases positive for the clinical sign, and the percentage is provided in brackets; the p value of significance is provided for comparison.

Stereotypes, profound ID, and bruxism were present in 68.1%, 67.8%, and 62.1% of the study group, respectively. Fewer than one-third (28.0%) had never learned to walk independently. Epilepsy before 5 years of age was present in 63.0% of patients; in 3.9% of seizures, onset was before 1 year of age, and seizures were not controlled or barely controlled by therapy in 21.4% (Table 3).

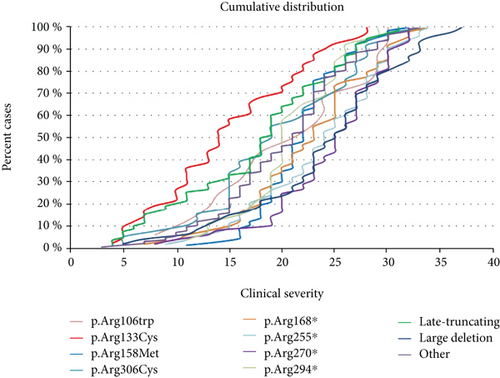

A severity score was computed for the MECP2-mutated patients [6]. Although there is wide variability in clinical severity, there is a clear effect of specific common MECP2 point mutations on median clinical severity. The cumulative distribution plots of patients positive for the MECP2 mutations showed that the missense mutation Arg133Cys and late truncating mutations are associated to the less severe phenotype (Figure 1(a)). The missense mutations Arg306, Thr158, and Arg106 (arginine or threonine can be replaced by any amino acid) and the early truncating mutation Arg294 ∗ belong to the intermediate severity phenotype. The remaining early truncating mutations (Arg168 ∗, Arg255 ∗, and Arg270 ∗) and large deletions are associated with the “most severe” form of RTT syndrome (Figure 1(a)).

The cohort of MECP2-mutated RTT patients included also two pairs of sisters carrying the same MECP2 mutation but with discordant clinical signs: one individual from each sibling pair could not speak or walk and had a profound intellectual deficit (classic RTT), while the other individual could speak and walk and had a moderate intellectual disability (Zappella variant). The five monozygotic twin pairs reported in RND were much more concordant than the sister pairs. Among the twin pairs, only two out of five had an identical clinical score, indicating that at least at this level of investigation, they were phenotypically identical. The remaining three twin pairs differed in specific fields such as epilepsy and weight (twin pair 1), level of speech and level of phrases (twin pair 2), or height, age of regression, and voluntary hand use (twin pair 3).

3.3. Patients Carrying a Mutation in CDKL5

RND contains 32 records for CDKL5 mutation-positive cases. Thirty-one patients had a diagnosis of the early-onset seizure variant of RTT, while one was diagnosed as atypical RTT. The most frequent mutations, representing the 50% of CDKL5-mutated patients, were truncating mutations (28.1% of late truncating and 21.9% of early truncating mutations) followed by missense mutations (31.2%) and large deletion (18.8%). In our cohort, the majority of patients had a normal head circumference at birth (93.8%), a deficient sphincter control (96.0%), feeding difficulties (97.4%), IQ < 40 (100%), and presence of hand stereotypies (85.7%) and had never spoken (82.6%) (Table 3).

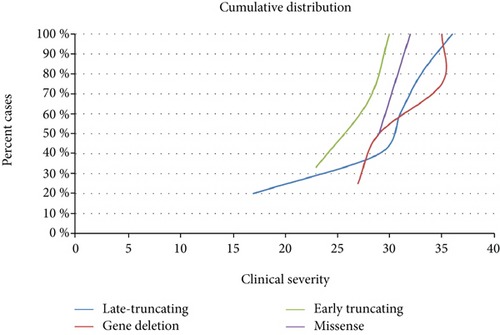

As for patients with MECP2 mutations, it was possible to compute the total score for the CDKL5-mutated patients. However, no correlation was observed between type of mutation and clinical severity (data not shown).

3.4. Patients Carrying a Mutation in FOXG1

RND contained 26 records for FOXG1 mutation-positive cases. Twenty-two patients had the congenital form of RTT, 2 patients had the classic form, and two patients were classified as atypical. The cumulative distribution of the patients positive for FOXG1 mutations showed a clear trend toward a less severe phenotype for FOXG1 late truncating mutations (Figure 1(b)). In our cohort, all patients carrying a FOXG1 mutation had IQ < 40, microcephaly, and no speech at examination (Table 3).

3.5. Comparison among the Three Groups

Epilepsy before 5 years of age was statistically significant among groups of patients (p value 0.0001 MECP2 vs. CDKL5 and p value < 0.044 MECP2 vs. FOXG1), since it was present in 63% of MECP2-mutated patients, in 96.9% (31 out of 32) of CDKL5 cases, and in 87.5% of FOXG1-mutated patients. The epilepsy that started before 1 year of age was present in 96.9% of CDKL5 patients with epilepsy, versus 3.9% of MECP2-mutated patients and 37.5% of FOXG1-mutated patients. Epilepsy was not controlled by therapy in 84% of CDKL5-mutated cases versus 21.4% of MECP2-mutated patients and 58.8% of FOXG1-mutated patients (Table 3).

Breathing dysfunction and eye pointing were statistically more frequent in MECP2 patients (53.5% and 87.6%, respectively) rather than in CDKL5 (11.5% and 40.6%, respectively) or FOXG1 (28% and 13.3%, respectively) patients (Table 3). Conversely, motor and verbal disabilities were more severe in CDKL5 and FOXG1 patients rather than in MECP2-mutated patients. About 92.3% of patients carrying a FOXG1 mutation had never spoken compared to the 59% of MECP2 and 82.6% of CDKL5-mutated patients. Moreover, FOXG1-mutated patients had never learned to sit (78.3%) and walk (91.3%) compared to MECP2 (7.7% and 28.0%, respectively) and CDKL5 (23.1% and 74.1%, respectively).

Other features such as normal head circumference at birth, deficient sphincter controls, feeding difficulties, height and weight below the 25th percentile, troubled nighttime sleeping, and cold extremities were very similar among the three groups of patients carrying a MECP2, CDKL5, or FOXG1 mutation (Table 3).

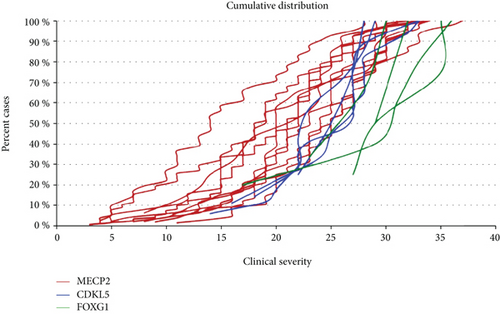

The overall cumulative distribution plot of patients carrying a mutation in the MECP2, CDKL5, or FOXG1 genes is illustrated in Figure 2. FOXG1 mutations confer the highest severity score, followed by CDKL5 mutations. The majority of MECP2 mutations are associated with the lowest severity score.

4. Discussion

Globally, the majority of RND patients do fulfill the necessary criteria for the diagnosis of RTT, according to the revised criteria [16]. A period of regression followed by recovery or stabilization, representing a required criterion for a diagnosis of RTT, is recorded in 96.2% of cases. The lack of recorded regression in nearly 4% of patients is probably due to the fact that in atypical RTT, especially in the congenital and early-onset seizure variants, the onset of neurological signs occurs in the first months of life, and in these cases, the regression is more difficult to ascertain.

Interestingly, although loss of acquired speech is included among RTT diagnostic criteria, RND data show that the majority of MECP2-positive cases have never spoken (59%), as reported in Table 3. Notably, hand stereotypies, although considered an invariant clinical sign of classic RTT, are absent in 31.9% of MECP2-mutated patients included in the RND dataset. It is however known that behind midline and exuberant hand stereotypies, many patients with MECP2 may show more varied stereotypies or subtle stereotypes, like pill rolling or tapping [18]. Interestingly, although 85.2% of the MECP2-positive patients have feeding difficulties, only 43.3% have gastrointestinal disturbances. This would suggest that part of the feeding difficulties arise from abnormal muscle tone and oropharyngeal dysfunction [19]. Even though breathing mechanisms in RTT preclinical models have been heavily investigated, breathing dysfunction “only” affects 53.5% of the patients carrying a mutation in MECP2 (Table 3). This is in line with a recent paper from the Rett Syndrome Natural History Study in which 51.6% of parents reported a history of hyperventilation, 67.1% a history of breath-holding, and 47.2% a history of air-swallowing during wakefulness [20].

Two earlier studies of the North American RTT Database relying on 915 patients with a mutation in MECP2 were published [21, 22]. Similar to the Australian database, the data relies on questionnaires sent out to families, and even if the questionnaires were analyzed by experienced clinicians, the patients were not all directly examined by the contributors. Available results mainly concern molecular data with the distribution and nature of reported mutations. It does not contain CDKL5 or FOXG1 molecular data and does not provide details concerning the major phenotypic traits present in the studied population. In Kirby et al., 87.4% of patients with MECP2 mutation have the typical form and 10.3% have the atypical form of RTT [22]. Similarly, the percentage of typical RTT patients with a MECP2 mutation in the RND is 84.7%. The cumulative distribution showed that there is a wide clinical variability within the same MECP2 mutation (Figure 1(a)). However, in accordance with previous reports [23, 24], the “mildest” mutations are Arg133Cys and late truncating mutations. The missense mutations Arg306, Thr158, and Arg106 (arginine or threonine can be replaced by any amino acid) and the early truncating mutation Arg294 ∗ belong to the intermediate severity phenotype. The remaining early truncating mutations (Arg168 ∗, Arg255 ∗, and Arg270 ∗) and large deletions are among the “most severe” form of RTT syndrome (Figure 1(a)). It is interesting to note that the plot of each mutation is not always parallel. For example, Thr158Met and Arg294 ∗ move more vertically, suggesting that the phenotype of patients who have these mutations is less influenced by other genetic or environmental factors.

Interestingly, the cohort of MECP2-mutated RTT patients included two pairs of sisters carrying the same MECP2 mutation but with discordant clinical signs. One individual from each pair could not speak or walk and had a profound intellectual deficit (classic RTT), while the other individual could speak and walk and had a moderate intellectual disability (Zappella variant) [25].

The phenotype of the patients carrying a mutation in CDKL5 and classified as having atypical RTT is much less documented than the classic RTT phenotype caused by MECP2 mutations. A report in 2013 described 86 patients with a mutation in CDKL5 with data originating from family questionnaires recorded in InterRett [26], and more recently, epilepsy and vagus nerve stimulation was studied in a cohort of 172 cases with a pathogenic CDKL5 mutation [27]. RND provided information in a cohort of 32 patients harboring a mutation in CDKL5. Expectedly, for the early seizure variant of RTT caused by CDKL5 mutations, the majority of patients experienced at least one episode of epilepsy (>90% in all three cohorts). The proportion of patients with a mutation in CDKL5 that never learned to walk in the three cohorts is also very similar (67.4% in InterRett, 64.6% in the International CDKL5 Disorder Database, and 74.1% in RND), together with the proportion of patients displaying hand stereotypies (80.3% of females in InterRett and 85.72% of patients positive for a mutation in CDKL5 in RND) [26, 27]. There is a difference between the two cohorts concerning the speech skills, since 30 out of 76 females (39.5%) with CDKL5 mutation acquired early speech skills in the InterRett cohort and 39/172 (22.7%) had the simplest level of communication in the International CDKL5 Disorder Database while only 17.4% females harboring a CDKL5 mutation had shown a somewhat level of speech in RND [26, 27].

Regarding CDKL5-mutated patients, no significant genotype-phenotype correlation was observed. The phenotype of the patients carrying a mutation in FOXG1 and classified as having atypical RTT is even less documented than the phenotype caused by CDKL5 mutations. The cumulative distribution in Figure 1(b) shows a clear trend toward a less severe phenotype for FOXG1 late truncating mutations. The cumulative overall distribution in Figure 2 nicely illustrates the progressive severity going from MECP2 to CDKL5 and FOXG1 mutation. CDKL5 patients lie in the most severe range in comparison to MECP2 patients with FOXG1 patients even more shifted than CDKL5 patients towards a worse clinical phenotype and a very minimum overlap with MECP2 patients.

In conclusion, the Rett Networked Database is a registry for patients with RTT where clinical data are validated by experienced clinicians upon direct examination of the affected individuals. One of the unique features of this database is its ability to collect a huge amount of clinical details, the collected clinical items being almost 300 with different levels of completeness, and genetic data [10–15]. RND collects data from 13 different countries; however, at the moment, it could not be considered representative of all the countries from which data is sourced given the different involvement of each country in terms of shared entries. Its strength is that it contains a large number of cases, thus providing a powerful resource to perform genotype-phenotype correlations of RTT patients from European countries and beyond. Overall, observation of RND data highlights clinical characteristics which occur more frequently in patients with a specific mutation (Table 3). For example, presence of regression and gait dyspraxia are statistically more frequent in MECP2-mutated patients; epilepsy and reduction in eye pointing capability are statistically more frequent in CDKL5-mutated patients, while the large majority of FOXG1 patients have never learned to walk, sit, and speak. Moreover, we observed that the majority of MECP2-mutated patients have the classic form of RTT, the majority of CDKL5-mutated patients have the early-onset variant, and the majority of FOXG1-mutated patients have the congenital form, with some exceptions (Figure 3). RND provides an open structure, available to all interested professionals, and a searchable web interface made available for registered users. These characteristics should prove useful to perform additional phenotype-genotype correlations, to better understand the typical and atypical forms of RTT, and to select adequate patient populations for future clinical trials.

Disclosure

Part of this work is reported in Grillo E et al., “Analysis of the phenotypes in the Rett Syndrome Networked Database.” European Society Human Genetics 2013 Meeting. Paris, France, June 8-11, 2013.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and their families who participated in this study. We thank Rossano Di Bartolomeo and Marco Maria D’Andrea, 3W Net Service, for their work in the construction of the database network. We thank Bela Melegh for contributing his patient data to the RND. This project was supported by IRSF (microgrant “Rett database network project” to AR), the Ricerca Corrente RETT-NGS 08C208 funds, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano (SR and FC) the ERARE EuroRETT Network, Danish Rett Syndrome Association, Association Française du Syndrome de Rett, Catalan Rett Association, Israel Rett Syndrome Association, and Associazione Italiana Rett (AIRETT). The BIRSS is grateful for the support from Rett UK. We also thank Rett Syndrome Europe (RSE) for strongly believing in this project.

Open Research

Data Availability

Data are available at https://www.rettdatabasenetwork.org/.