Modeling Temperature and Pricing Weather Derivatives Based on Temperature

Abstract

This study first proposes a temperature model to calculate the temperature indices upon which temperature-based derivatives are written. The model is designed as a mean-reverting process driven by a Levy process to represent jumps and other features of temperature. Temperature indices are mainly measured as deviations from a base temperature, and, hence, the proposed model includes jumps because they may constitute an important part of this deviation for some locations. The estimated value of a temperature index and its distribution in this model apply an inversion formula to the temperature model. Second, this study develops a pricing process over calculated index values, which returns a customized price for temperature-based derivatives considering that temperature has unique effects on every economic entity. This personalized price is also used to reveal the trading behavior of a hypothesized entity in a temperature-based derivative trade with profit maximization as the objective. Thus, this study presents a new method that does not need to evaluate the risk-aversion behavior of any economic entity.

1. Introduction

Temperature-based derivatives represent a new financial tool to buy and sell a natural phenomenon. Doing so requires two things: a unit of measurement for the natural phenomenon that everyone agrees upon and a price that may facilitate a transaction. This study is designed to evaluate these two requirements.

Some preexisting measures already appear in the form of indices to meet the first requirement. To find values for these indices, the literature contains several temperature models using mean-reverting processes as the main tool. The most cited study develops an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process to model temperature [1]. Using the equivalent martingale measures approach, the authors determine the price of an option. Benth and Šaltytė-Benth [2] model temperature as a continuous time autoregressive process for Stockholm and report a clear seasonal variation in regression residuals. They propose a model using a higher-order continuous time autoregressive process, driven by a Wiener process with seasonal standard deviation. While pricing futures and options, they consider a Gaussian structure in the temperature dynamics. In another study [3], they model temperature with an OU process driven by a generalized Levy process. The model contains seasonal mean and volatility. Instead of dynamic models, some authors offer time-series models to represent temperature. Campbell and Diebold [4] apply a time series approach to model temperature, including trend seasonality represented by a low-ordered Fourier series and cyclical patterns represented by autoregressive lags. The contributions to conditional variance dynamics are coming from seasonal and cyclical components. The authors used Fourier series and GARCH processes to represent seasonal volatility components and cyclical volatility components, respectively. Jewson and Caballero [5] discuss the use of weather forecasts in pricing weather derivatives, presenting two methods for strong seasonality in probability distributions and the autocorrelation structure of temperature anomalies. Elias et al. [6] develop four regime-switching models of temperature for pricing temperature based derivatives and find that a two-state model governed by a mean-reverting process as the first state and by a Brownian motion as the second state was superior to the others. Schiller et al. [7] and Oetomo and Stevenson [8] provide a comparison of different models.

To comply with the first requirement, the current study offers a temperature model based on Alaton et al. [1], which was defined after analyzing temperature data from different locations. The temperature model in this study is a mean-reverting Levy process. The Levy part contains a Brownian motion and two mean reverting jump processes driven by compound Poisson processes. For some flexibility, the jumps are designed as slow and fast mean-reverting processes, which are independent. The main difference with the model proposed here is its inclusion of jumps. Because temperature indices are mainly calculated as deviation of temperature from a base temperature, the model assumes that jumps are inevitable, at least for certain locations. The numerical estimates in this study contain test results related to this issue. The solution to the proposed temperature model is applied inversion formula to obtain approximated expected value of a specific index type and to obtain the approximated distribution of the same index.

Notably, temperature has unique behavior for any location in which it is measured. Therefore, it is not possible to develop a single model that explains every temperature behavior in every location. In addition, more than 100,000 weather stations worldwide measure temperature for different periods. It may even be difficult to develop a temperature model that is valid for all time at a single location. Thus, this study aims to cover more locations and periods by simply using a flexible model that can include or exclude jumps.

The second requirement, temperature-based derivatives pricing, is more complicated. Because the underlying commodity is not a traded asset, weather derivatives based on temperature have an incomplete market [9]. Carr et al. [10], Magill and Quinzii [11], and El Karoui and Quenez [12] provide a general discussion of incomplete markets. Pricing temperature-based derivatives is mainly based on two approaches: dynamic valuation and equilibrium asset pricing. The dynamic pricing approaches [1, 2] were discussed above. For equilibrium pricing, Cao and Wei [13] use a generalization of the Jr. Lucas model [14], which considers weather as another source of uncertainty. Richards et al. [15] suggest another equilibrium model. Davis [16] uses the marginal substitution value approach for pricing in incomplete markets. In addition, Xu et al. [17] use another classification for pricing temperature-based derivatives and add actuarial pricing and extended risk-neutral valuation in addition to equilibrium asset pricing, where the former is based on Jewson and Brix [18] and the latter on Hull [19] and Turvey [20]. In addition, some researchers used Monte-Carlo simulations in pricing temperature-based derivatives [21].

This study bases its pricing on the monetary effect of the natural phenomenon on economic entities. Further, this study shows that temperature has different effects on different entities. The same temperature may have a positive effect on one entity and a negative effect on another and is therefore personal, ceteris paribus. Thus, the study develops a personal price, which may require a determination of the entity’s risk aversion behavior. To address this problem, this study focuses on entity-specific trading behavior rather than the entity’s risk aversion behavior in order to develop a more realistic approach by avoiding an inconclusive debate over the risk premiums and utility functions used to calculate risk premiums. Moreover, a benefit of the proposed pricing model is that it is independent from how researchers measure temperature.

Critics may object to the move from a stochastic temperature model to some form of actuarial pricing model. There are several reasons for this move: first, this study demonstrates that risk-neutral pricing ends up with super-hedging; second, the discussion about risk premiums in the literature is unclear; and, finally, the calculations of jump processes needed approximations to obtain certain results. These considerations led to this study’s development of a more appropriate and practical method.

The second section of the paper provides the approximated index calculation and distribution of temperature after presenting a temperature model. Third section develops individualized prices and discusses the trading behavior of a hypothetical entity. The paper then presents the study’s conclusions.

2. Model

2.1. The Temperature Model

To find the value of a temperature-based derivative, one needs the distribution of the underlying temperature given in (9). However, this does not have a closed-form solution. One way to address this problem is to use a characteristic function of the temperature and apply inversion techniques to find the value of an HDD, an approximated distribution of CHDD, and an approximated distribution for temperature itself.

2.2. Characteristic Function of Temperature

Let A = iuμye−α and . Let eαr = g(r). Then, .

Further, let D(r) = Ag(r) − Bg2(r), where eD(r) = 1 + D(r) + D2(r)/2! + ⋯.

2.3. HDD and Distribution Function

This part of the study focuses on measuring HDDs. It is easy to apply the calculations into other types of indices. In the current case, inversion techniques will be used to find the value of an HDD and its distribution and hence the CHDD values.

2.3.1. Approximating Density Function of Temperature

2.3.2. Measuring HDD

HDDs are clearly contingent claims on how temperature deviates from a base temperature. As one way to find the expected value of an HDD, this study will first find its Fourier transform. Then, the inverse Fourier transform will be applied to both the HDD’s Fourier transform and the characteristic function of temperature [24].

Let x = Tt, w(x) is HDD’s payoff function given in (2), Base = B, and is its generalized Fourier transform. Then, .

The characteristic function of Λt can be obtained from (15) and written as ∅Λ(u) = exp (iu((1 − e−bt)/b) {y0e−α + λyμy((1 − e−α)/α) + z0e−β + λzμz((1 − e−β)/β)} − (1/2)u2((1 − e−2bt)/2b) + .

2.3.3. Numerical Estimates

The success of the proposed temperature model and (24) were tested in terms of forecasting Cooling Degree Day (CDD), which is another index based on temperature, and HDD values for the 12 cities listed in Tables 1 and 2. CDD is calculated as CDDi = max (0, Ti − Base), where Base is a predetermined temperature level and Ti is the average temperature calculated as in (1). Cumulative CDD (CCDD) is calculated using , where CDDi is calculated as in the previous sentence and N is the time horizon, which is generally a month or season. The test assumes a base temperature of 18 degrees Celsius and proceeds in the following manner:

| City | Actual | The current model | Years ∗ | Error (%) | Campbell | Error (%) | Benth | Error (%) | HBA | Error (%) | Equation (24) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 6047 | 4980 | 5 | −17.65 | 6203 | 2.58 | 5377 | −11.08 | 5940 | −1.77 | 6398 | 5.81 |

| Beijing | 5880 | 5705 | 5 | −2.98 | 5571 | −5.26 | 5039 | −14.30 | 5319 | −9.54 | 6218 | 5.75 |

| Cairo | 573 | 322 | 29 | −43.81 | 746 | 30.20 | 353 | −38.39 | 701 | 22.34 | 718 | 25.31 |

| Chicago | 5980 | 5814 | 15 | −2.78 | 6098 | 1.97 | 5849 | −2.19 | 6337 | 5.97 | 3560 | −40.67 |

| Dallas | 2151 | 1777 | 34 | −17.39 | 2202 | 2.37 | 1767 | −17.85 | 2176 | 1.16 | 1118 | −48.02 |

| Istanbul | 3607 | 2872 | 9 | −20.38 | 3808 | 5.57 | 2972 | −17.61 | 3485 | −3.38 | 4520 | 25.31 |

| LA | 1441 | 1250 | 21 | −13.26 | 1127 | −21.79 | 1119 | −22.35 | 1244 | −13.67 | 1608 | 11.59 |

| New York | 4378 | 4391 | 7 | 0.30 | 4699 | 7.33 | 4516 | 3.15 | 4683 | 6.97 | 4949 | 13.04 |

| Paris | 3940 | 4988 | 6 | 26.60 | 5006 | 27.06 | 4190 | 6.35 | 4781 | 21.35 | 4902 | 24.42 |

| Sydney | 1277 | 1000 | 37 | −21.70 | 1381 | 8.14 | 1002 | −21.54 | 1343 | 5.17 | 1086 | −14.96 |

| Tokyo | 2925 | 2648 | 8 | −9.47 | 3238 | 10.70 | 2671 | −8.68 | 764 | −73.88 | 3309 | 13.13 |

| Washington | 3572 | 3758 | 34 | 5.21 | 3751 | 5.01 | 3724 | 4.26 | 3851 | 7.81 | 3749 | 4.96 |

- ∗Number of years of data included in estimations.

| City | Actual | The current model | Years ∗ | Error (%) | Campbell | Error (%) | Benth | Error (%) | HBA | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 426 | 742 | 5 | 74.18 | 175 | −58.92 | 412 | −3.29 | 417 | −2.11 |

| Beijing | 1576 | 1542 | 19 | −2.16 | 1214 | −22.97 | 1647 | 4.51 | 1447 | −8.19 |

| Cairo | 3221 | 4243 | 5 | 31.73 | 2763 | −14.22 | 3427 | 6.40 | 3218 | −0.09 |

| Chicago | 1071 | 771 | 7 | −28.01 | 647 | −39.59 | 866 | −19.14 | 909 | −15.13 |

| Dallas | 3585 | 2556 | 5 | −28.70 | 2353 | −34.37 | 2903 | −19.02 | 2792 | −22.12 |

| Istanbul | 1428 | 1297 | 5 | −9.17 | 792 | −44.54 | 1224 | −14.29 | 1089 | −23.74 |

| LA | 426 | 490 | 32 | 15.02 | 569 | 33.57 | 495 | 16.20 | 681 | 59.86 |

| New York | 1297 | 1104 | 7 | −14.88 | 906 | −30.15 | 988 | −23.82 | 1046 | −19.35 |

| Paris | 264 | 118 | 8 | −55.30 | 63 | −76.14 | 189 | −28.41 | 314 | 18.94 |

| Sydney | 1308 | 1251 | 9 | −4.36 | 840 | −35.78 | 1206 | −7.80 | 1157 | −11.54 |

| Tokyo | 1832 | 1608 | 18 | −12.23 | 1282 | −30.02 | 1716 | −6.33 | 434 | −76.31 |

| Washington | 1927 | 1739 | 8 | −9.76 | 1451 | −24.70 | 1503 | −22.00 | 1609 | −16.50 |

- ∗Number of years of data included in estimation.

Data. Temperature data is available for 12 cities covering 38 years from 1974 to 2011. The first part uses 37 years of data to estimate the parameters. The temperature data for 2011 were used to compare with one-year-ahead predictions. Temperature data were obtained from the National Climatic Data Center.

Design. A simulation was designed to run in two dimensions: the first on different cities and the second to capture changes in the parameters through time for each city. In this respect, the initial simulations used the last 5 years of data. They were then continued by including one more year of data to the existing data in each turn where HDD and CDD estimates were calculated. A turn consisted of 10,000 simulation runs. Then, the simulation results were compared with actual HDD and CDD values. Finally, the parameters of the year that offered the best estimates of the HDDs and CDDs were chosen for use in the one-year-ahead predictions.

Parameter Estimation. Parameters were estimated as defined in [1, 27, 29].

Simulation of Jumps. Because they have a different structure, jumps were simulated separately and the results added to the discretized model. For this aim, the jumps were detected by first removing the mean from the actual data and selecting the values above two standard deviations. These jumps were then separated into two categories: single and multiple jumps to constitute fast and slow mean reverting jumps, respectively. The sample means and sample standard deviations of these two jump groups were found to simulate jump sizes. In addition, the intensities were found by The simulation consisted of 10,000 runs, during which the jump times were first found by using intensities. Then, for each run, random draws were taken using means and standard deviations obtained from data. Finally, the discretized jumps were added to the discretized jump model.

After these phases, one-year-ahead predictions were conducted along with three other models: the Campbell and Diebold [4] model (Campbell Model), the Benth and Šaltytė-Benth [2] model (Benth Model), and the Historical Burn Analysis (HBA) model that calculates historical averages. In addition, HDD predictions were calculated based on (24). This yielded the results in Tables 1 and 2. In the Appendix, the parameter estimates for HDD and CDD values are presented, in Tables 3 and 4, respectively, including the time period used to obtain these parameters. In addition, statistical test values of these parameters are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

| City | Year ∗ | A | B | C | Phase | b | Gamma_0 | Gamma_1 | Fast_Inten | Fast_Mean | Fast_sd ∗∗ | Slow_Inten | Slow_Mean | Slow_sd | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 5 | 50.19 | 0.001854 | 21.32 | −2.77 | 0.193962 | 95.952994 | 0.9637143 | 0.0016438 | −0.5543834 | 0.4924429 | 0.0054795 | −6.1314104 | 5.1345993 | 0.3835657 |

| Beijing | 5 | 56.73248 | −0.00176 | 27.72651 | −2.89336 | 0.372348 | 66.177766 | 0.9800345 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00109589 | −3.161959 | 2.420366 | 0.47568 |

| Cairo | 29 | 70.23189 | 0.000344 | 13.68758 | −2.72869 | 0.345847 | 239.81369 | 0.9547672 | 0.0042513 | −0.4124696 | 1.585721 | 0.00302315 | −1.690717 | 2.075651 | 0.703044 |

| Chicago | 15 | 50.57 | 0.00014 | 24.71 | −2.79 | 0.271967 | 117.25 | 0.961314 | 0.004414 | −3.119119 | 2.524564 | 0.005632 | −6.375580 | 5.517740 | 0.343206 |

| Dallas | 34 | 65.31678 | 0.000232 | 20.00168 | −2.83072 | 0.298336 | 294.61489 | 0.936274 | 0.0045931 | −2.4987494 | 2.391683 | 0.00604351 | −6.1932845 | 4.966445 | 0.291944 |

| Istanbul | 9 | 58.54 | 0.00081 | 18.12 | −2.67 | 0.237101 | 184.55 | 0.947974 | 0.004262 | −0.958549 | 2.047743 | 0.002740 | −3.133173 | 1.813471 | 0.562597 |

| Los Angeles | 21 | 63.82858 | −0.0001 | 6.651395 | −2.4675 | 0.230077 | 338.75801 | 0.9166473 | 0.0062622 | 0.3575345 | 1.352837 | 0.01108937 | 0.81062689 | 2.798516 | 0.460403 |

| New York | 7 | 54.63592 | 0.000548 | 21.77908 | −2.71524 | 0.286476 | 165.02405 | 0.9447895 | 0.0015656 | −1.6825421 | 2.360227 | 0.00508806 | −3.8112152 | 3.30503 | 0.684576 |

| Paris | 6 | 54.58335 | −0.00122 | 15.45061 | −2.83361 | 0.21059 | 147.12152 | 0.9490173 | 0.0054795 | −0.0954452 | 1.895953 | 0.00547945 | −1.67898 | 3.505224 | 0.554255 |

| Sydney | 37 | 63.451 | 0.000154 | 9.494916 | −2.8139 | 0.647759 | 526.99911 | 0.876059 | 0.0146612 | 1.5064313 | 2.606529 | 0.0033321 | 1.5601199 | 3.226385 | 0.911471 |

| Tokyo | 8 | 61.22 | 0.000375 | 18.38 | −2.61866 | 0.530895 | 180.28 | 0.954846 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Washington | 34 | 58.62177 | 3.04E − 05 | 21.75468 | −2.79459 | 0.279335 | 173.30119 | 0.9524289 | 0.0045125 | −1.9805768 | 1.755655 | 0.00354553 | −4.9014241 | 4.06658 | 0.388133 |

- ∗Year represents amount of data in years that produced best estimation results.

- ∗∗sd means standard deviation.

| City | Year ∗ | A | B | C | Phase | b | Gamma_0 | Gamma_1 | Fast_Inten | Fast_Mean | Fast_sd ∗∗ | Slow_Inten | Slow_Mean | Slow_sd | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 5 | 50.19 | 0.001854 | 21.32 | −2.77 | 0.193962 | 95.952994 | 0.9637143 | 0.0016438 | −0.5543834 | 0.4924429 | 0.0054795 | −6.1314104 | 5.1345993 | 0.3835657 |

| Beijing | 19 | 54.96688 | 3.03E − 06 | 27.14738 | −2.91682 | 0.351405 | 63.312073 | 0.980961 | 0.000721 | −1.5276715 | 1.531992 | 0.00100937 | −2.9315846 | 2.019894 | 0.385117 |

| Cairo | 5 | 71.94036 | 0.002198 | 13.39397 | −2.74021 | 0.36773 | 104.83607 | 0.983445 | 0.0021918 | 0.3088935 | 1.644226 | 0.00273973 | −1.7313942 | 0.945926 | 0.544186 |

| Chicago | 7 | 51.70 | −0.00034 | 25.18 | −2.80 | 0.253619 | 108.27 | 0.963663 | 0.003131 | −3.281461 | 3.025694 | 0.005871 | −5.240072 | 4.234712 | 0.397902 |

| Dallas | 5 | 69.85579 | −0.00172 | 20.02312 | −2.83355 | 0.269534 | 314.92838 | 0.934 | 0.0032877 | −3.2390974 | 1.069774 | 0.00657534 | −3.3012769 | 3.345035 | 0.4432 |

| Istanbul | 5 | 59.32 | 0.00134 | 18.10 | −2.69 | 0.264510 | 183.29 | 0.949545 | 0.002192 | 0.067349 | 0.601966 | 0.002740 | −2.406968 | 1.833246 | 0.561837 |

| Los Angeles | 32 | 63.81324 | −5.64E − 05 | 6.699702 | −2.46624 | 0.208063 | 312.82723 | 0.9232099 | 0.0058219 | 0.3913695 | 1.425177 | 0.00984589 | 1.02398907 | 3.358289 | 0.40139 |

| New York | 7 | 54.63592 | 0.000548 | 21.77908 | −2.71524 | 0.286476 | 165.02405 | 0.9447895 | 0.0015656 | −1.6825421 | 2.360227 | 0.00508806 | −3.8112152 | 3.30503 | 0.684576 |

| Paris | 8 | 54.66317 | −0.00085 | 15.5993 | −2.83742 | 0.218952 | 150.30161 | 0.9485509 | 0.005137 | −0.4207048 | 1.581089 | 0.00513699 | −0.1355112 | 4.770146 | 0.255761 |

| Sydney | 9 | 65.07105 | 0.000171 | 9.53934 | −2.86309 | 0.535114 | 426.96927 | 0.9023923 | 0.0152207 | 1.6436984 | 1.81751 | 0.00182648 | 2.58516471 | 2.615411 | 0.764766 |

| Tokyo | 18 | 61.60 | 3.13E − 05 | 18.53 | −2.63 | 0.497182 | 214.39 | 0.944722 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Washington | 8 | 57.7754 | 0.000801 | 22.01289 | −2.78212 | 0.284276 | 169.0818 | 0.9526032 | 0.0041096 | −1.6365612 | 1.493845 | 0.00376712 | −3.2540612 | 2.309414 | 0.561109 |

- ∗Year represents amount of data in years that produced best estimation results.

- ∗∗sd means standard deviation.

| City | A | B | C | Phase | Gamma_0 | Gamma_1 | Fast_Mean | Slow_Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0.00263 | 0.1609 | 0 |

| Beijing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0.0082 | 0.3174 | 0.02142 |

| Cairo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.0879 | 0 |

| Chicago | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dallas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Istanbul | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.1021 | 0 |

| Los Angeles | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.07382 | 0 |

| New York | 0 | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.001 | 0.2038 | 0 |

| Paris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.01 | 0.8557 | 0.01075 |

| Sydney | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| Tokyo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | NA | NA |

| Washington | 0 | <0.05 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

- NS: not statistically significant.

- NA: not available.

| City | A | B | C | Phase | Gamma_0 | Gamma_1 | Fast_Mean | Slow_Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankara | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | 0.00263 | 0.1609 | 0 |

| Antalya | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.3143 | 0.7321 |

| Beijing | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | NS | 0 | 0.096 | 0 |

| Bursa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.3216 | 0 |

| Cairo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.6717 | 0.001395 |

| Chicago | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | <0.01 | 0 | 0.03218 | 0 |

| Dallas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.01897 | 0 |

| Istanbul | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.7978 | 0 |

| Los Angeles | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0.02789 | 0 |

| New York | 0 | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.001 | 0.2038 | 0 |

| Paris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.01 | 0.3038 | 0.8347 |

| Sydney | 0 | <0.01 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS | 0 | 0.0056 |

| Tokyo | 0 | <0.01 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.01 | NA | NA |

| Washington | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0 |

- NS: not statistically significant.

- NA: not available.

2.3.4. Analysis of Numerical Estimates

The best estimates of HDDs and CDDs were obtained for different periods as shown in the Appendix. This is mainly a characteristic of the temperature since it changes in its long-term behavior. However, this may not be a good way to use all existing data for a city. Instead, every location must be scanned and evaluated for different time periods to obtain the best prediction results. In addition, the current model is equally successful in HDD and CDD predictions.

Having a good estimate of HDD and CDD values does not necessarily correspond to the best fit of the model to temperature data. This may be because including the jumps may result in a better estimation of index values while deteriorating the fit of the model to the data.

The current model demonstrates its capacity related to the changing conditions of the temperature data. For example, in Chicago, both jump types were statistically significant and the model predicted HDDs accurately. On the other hand, Tokyo did not have any jumps during entire period, and the current model was still able to make accurate predictions for HDDs. Interestingly, the Historical Burn Analysis containing long-term HDD and CDD averages provided successful predictions. These results suggest that temperatures do not change significantly for certain locations.

As expected, the approximated HDD calculations obtained from (24) were less accurate than the simulations. Nevertheless, the predictions based on the equation were still successful. The estimated HDDs of Los Angeles and Washington were better than any other model. Finally, while this study conducted comparisons for only 12 stations, there are 125,000 weather stations worldwide. It is therefore impossible to say that one model is superior to the others, though the current model and (24) were successful in certain locations and periods, which merits evaluation.

3. Pricing

This section addresses temperature risk and its differences from classical asset risks before providing a fair price for a temperature-based derivative written of HDD with real probabilities. Next, this section shows that the price of the derivative will be super-hedging when using risk-neutral probabilities. Finally, a personal price will be developed based on personal temperature risk.

3.1. Temperature Risk

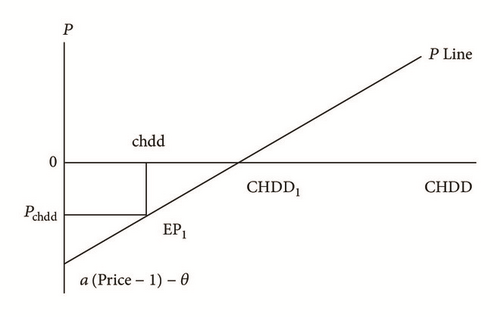

A positive value for a in (26) indicates that the company can sell a certain amount of its products, even in the case of zero CHDD. Similarly, a positive value for b in the same equation represents a positive relationship between sales and CHDDs.

To guarantee a positive profit after a certain amount of CHDDs is realized, assume that Price > 1 and constant.

The aim is to construct a relationship between CHDD and profit functions to ascertain the magnitude of the effect of temperature on the company. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship, with the assumption that θ > a∗Price initially provides negative profits.

Figure 1 constructs a relationship between CHDD and profit such that every CHDD value now represents a monetary value in terms of positive and negative profits. Figure 1 shows a deterministic relationship between CHDD level and profit. The CHDD value for the proposed period is unknown.

It is clear that the magnitude of TR will depend on business type and size. For example, for a gas company, a decrease in the index value means a lower value in sales. However, at the same time, this decrease may result in an increase in the sales of a beverage company. The magnitude of the decrease or the increase in profits, on the other hand, will be directly related to the size of the business.

3.2. An Approximated Fair Price of a Temperature Based Put Option

Equation (32) provides an actuarial price since it is based on expected values. Derivative pricing using real probabilities may require an evaluation of risk premiums. The literature offers only inconclusive discussions. For example, Hull [19] states that it is possible to calculate the payoffs of weather derivatives with real probabilities because these derivatives have no systemic risk. Turvey [30] supports this idea. On the other hand, Chincarini [31] examines the efficiency of weather futures in CME in HDD and CDD futures assuming an efficient market and risk premiums varying from negative to positive values across cities. In addition, Cao and Wei [13] highlighted the importance of the market price of risk for weather derivatives. This study will follow a different path by evaluating the trading behavior of a candidate company instead of the company’s risk behavior. The next section will show the outcome of using risk-neutral probabilities in (32).

3.3. Risk-Neutral Pricing

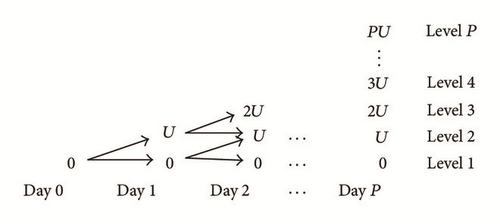

In this part, the put option of the previous section will be priced using risk-neutral probabilities in a binomial model. CHDD is clearly composed of HDDs. A closer look at HDDs reveals that realizations of HDDs can be represented by a binomial model such that if HDD is realized, there will be an upward movement as in the binomial model; otherwise, in case of a downward movement, there will be 0. The calculations were done according to Björk [32]. For the up movement, the best candidate for HDD will be the mean value of an HDD calculated using (24). Let U = (24). Figure 2 represents the binomial model.

The probability of an upward movement, pu, is found by , while the probability of downward movement is equal to pd = 1 − pu. Let risk-free rate R = 0. The model satisfies the condition of being arbitrage-free in the form of d ≤ 1 + R ≤ u by definition. The martingale measure for the current model is CHDDt = EQ[CHDDt+1]. As in Björk [32], if it is set K = PU, the value of the option will be equal to K itself.

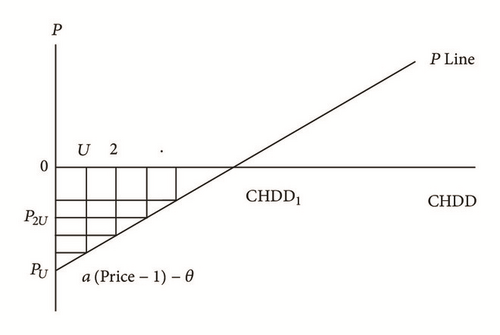

The above results from the fact that CHDD is a summation process and certainly a submartingale compared to the underlying asset of an ordinary option. The only possibility to obtain a martingale form of the underlying process CHDD is then to consider the whole summation process and reflect it as a constant. Reexamining Figure 1 reveals one interesting implication of this result. Figure 3 is a combination of Figures 1 and 2.

In Figure 3, each level of TR is connected to upward movements created by HDDs. This time, TR becomes a super-martingale; when TR is converted into a martingale, it will be equal to TTR, a situation known as super-hedging. Put simply, it means hedging the total risk. In pricing, the price of the hedge will be equal to total risk. Using the total risk instead of actual risk will definitely prevent any form of transaction, for both hedge suppliers and demanders. Therefore, using risk-neutral probabilities is not ideal for pricing a temperature-based derivative. With these unclear results from the risk premiums and the inappropriateness of using risk-neutral probabilities, the current study offers the following for pricing temperature-based derivatives.

3.4. A New Setup for Pricing

In this setup, any economic entity, an individual or a company, will try to achieve an objective. In this case, the natural objective for the hypothetical company is to maximize its expected profit given in (29). Then, the issue is determining the conditions under which this company will maximize its profits. The answer will reveal the company’s trading behavior. Consider Proposition 1.

Proposition 1. The company will buy a put option if the following condition is satisfied:

Proof. Equation (29) is the expected profit when there is no trade for options. If there is a chance to trade an option, the company will prefer a put option with a strike value equal to CHDD1 from Figure 1. Assume that the company buys a put option equal to ϵ with a cost of C. There will be two states at the end of the determined period depending on the payout of the option. The setup is given in the following.

Let x represent CHDD. Then, one has the following.

State 1

Additionally, the profit function in the no trade case is also reflected in the left hand side of the equation with a probability of 1. Consequently, subtracting the right hand side from the left hand side will result in

Although the above calculations are given for a candidate company, since profit function dropped out and the tick value is equal to $1, (33) defines a general case valid for any company dealing with a put option with K = CHDD1. Thus, the following definition is given for the case E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) = C.

Definition 2. When E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) = C, C is the general price, which is valid for any economic entity.

Definition 3. The personalized price for the put option E[max(K − x, 0)] is given by

3.5. Discussion of the New Pricing Setup

Equation (33) defines the profitable conditions for the company, of which there are three. When E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) ≥ C, the company will buy the option. If E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) = C, the company will be indifferent between buying the option or doing nothing. Finally, when E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) ≤ C, it is the best interest of the company to sell the option because it maximizes profit. The value of C when E[max(K − x, 0)]N(K − PB + PM∗) = C can be defined as the fair price since it does not result in a positive profit.

From here, a connection between the current approach and the utility approach can be established. Since the current setup is based on profit maximization, it coincides with the utility approach based on wealth maximization. The gain is that this statement is true for any utility function choices.

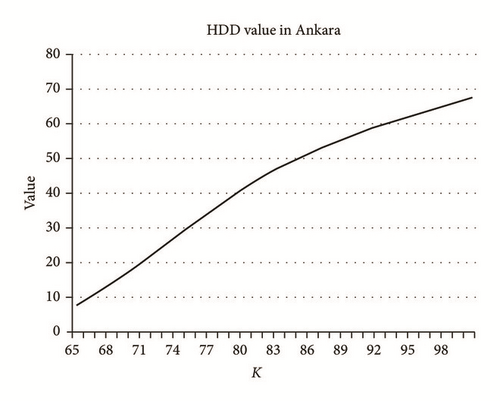

A numerical one-day-ahead estimate of temperature for the price of an HDD for Ankara was developed using (33) and (32). The mean and standard deviation of the approximated distribution were calculated according to (18) and (19). The value of C in (19) was approximated by conditional variance of the ARCH model. The tick value was taken as $1, and the strike value K was taken as an interval from 65 to 100. The estimated values are shown in Figure 4.

As mentioned earlier, (33) defines a general price and trading behaviors for any company since the equation does not include the profit function. This generality does not give much insight into what a put option with a strike value of K actually means for a specific company. This deficiency was corrected by replacing the tick value with (40) because, unlike ordinary assets, temperature affects economic entities on different scales. Thus, a personalized price must apply for each economic entity. Moreover, (40) and Definition 3 state that the hypothetical company will enter a trade for the option if there is a possibility for arbitrage. If the fair price is available, the company will be indifferent to entering a trade or doing nothing. In the new pricing setup, the expected profit will always be the maximum, as will be the company’s utility. Risk aversion will negatively affect the maximum profit and utility. Therefore, having a maximum profit and the resulting maximum utility will direct the company to follow the presented approach rather than the one of suboptimal risk aversion.

4. Conclusions

Derivatives written on temperature are based on index values obtained from temperature data, which are essentially measured as deviations of temperature from a threshold value. This makes measuring deviations from a base temperature in the form of jumps important for any temperature model for some locations. This study proposed and demonstrated a temperature model that included different kinds of jumps that was then handled using different techniques. In addition, unlike existing models that consider temperature risk as the result of the temperature itself, like in stocks, the proposed model shows that financial risk caused by temperature differs from classical asset risk, though this risk depends on the type of business. This study demonstrated a method to measure this temperature risk. Moreover, almost all of the existing pricing methods are based on risk-neutral valuations. The results from this study showed that risk-neutral valuation in temperature-based derivatives ends with super-hedging. Finally, the current study offers a pricing scheme that differs from classical pricing approaches that are based on risk-neutrality or risk-aversion concepts. Instead of utility functions, this study employs a more realistic and practical approach in terms of objective functions set by the firm itself. In return, the model provides a personalized price based on company-specific temperature risk to realize an objective in terms of profit.

Disclosure

This paper is based on the Ph.D. thesis by Birhan Taştan, titled “Modeling Temperature and Pricing Weather Derivatives Based on Temperature,” which was presented at the Middle East Technical University, Institute of Applied Mathematics, in the year 2016.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.