Plane Waves and Fundamental Solutions in Heat Conducting Micropolar Fluid

Abstract

In the present investigation, we study the propagation of plane waves in heat conducting micropolar fluid. The phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth are computed numerically and depicted graphically. In addition, the fundamental solutions of the system of differential equations in case of steady oscillations are constructed. Some basic properties of the fundamental solution and special cases are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Eringen [1] developed the theory of microfluids, in which microfluids possess three gyration vector fields in addition to its classical translatory degrees of freedom represented by velocity field. Eringen introduced the micropolar fluids [2] which are subclass of these fluids, in which the local fluid elements possess rigid rotations without stretch. Micropolar fluids can support couple stress, the body couples, and asymmetric stress tensor and possess a rotational field, which is independent of the velocity of fluid. Anisotropic fluids, liquid crystals with rigid molecules, magnetic fluids, cloud with dust, muddy fluids, biologicaltropic fluids, and dirty fluids (dusty air and snow) over airfoil can be modeled more realistically as micropolar fluids. Ariman et al. [3, 4] studied microcontinuum fluid mechanics. Říha [5] discussed the theory of heat conducting micropolar fluid with microtemperature. Eringen and Kafadar [6] developed polar field theories. Brulin [7] discussed linear micropolar media. Flow and heat transfer in a micropolar fluid past with suction and heat sources were discussed by Agarwal and Dhanapal [8]. Payne and Straughan [9] investigated critical Rayleigh numbers for oscillatory and nonlinear convection in an isotropic thermomicropolar fluid. Gorla [10] studied combined forced and free convection in the boundary layer flow of a micropolar fluid on a continuous moving vertical cylinder. Eringen [11] investigated the theory of microstretch and bubbly liquids. Aydemir and Venart [12] investigated the flow of a thermomicropolar fluid with stretch. Yerofeyev and Soldatov [13] discussed a shear surface wave at the interface of an elastic body and a micropolar liquid. The theory of elastic and viscoelastic micropolar liquids was studied by Yeremeyev and Zubov [14]. Hsia and Cheng [15] discussed longitudinal plane waves propagation in elastic micropolar porous media. Hsia et al. [16] studied propagation of transverse waves in elastic micropolar porous semispaces.

Construction of fundamental solution of systems of partial differential equations is necessary to investigate the boundary value problems of the theory of elasticity and thermoelasticity. The fundamental solutions in the classical theory of coupled thermoelasticity were firstly studied by Hetnarski [17, 18]. Hetnarski and Ignaczak [19] studied generalized thermoelasticity. Svanadze [20–25] constructed the fundamental solutions in the microcontinuum field theories. Kumar and Kansal [26] investigated the fundamental solution in the theory of thermomicrostretch elastic diffusive solids. Fundamental solution in the theory of micropolar thermoelastic diffusion with voids was studied by Kumar and Kansal [27]. Recently, Kumar and Kansal [28] discussed plane waves and fundamental solution in the generalized theories of thermoelastic diffusion. Kumar and Kansal [29] studied propagation of plane waves and fundamental solution in the theories of thermoelastic diffusive materials with voids. The information related to fundamental solutions of differential equations is contained in the books of Hörmander [30, 31].

The main objective of the present paper is to study the propagation of plane waves in heat conducting micropolar fluid. Several qualitative characterizations of the wave field, such as phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth, are computed and depicted graphically for different values of frequency. The representation of fundamental solution of system of equations in the case of steady oscillations is obtained in terms of elementary functions. Some particular cases have also been deduced.

2. Basic Equations

In three-dimensional space E3, let x = (x1, x2, x3) be the points of the Euclidean space, t represents the time variable, and Dx = (∂/∂x1, ∂/∂x2, ∂/∂x3).

3. Solution of Plane Waves

The expressions for phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth of above waves are derived as follows.

4. Steady Oscillations

Definition 1. The fundamental solution of the system of (21)-(22) (the fundamental matrix of operator F) is the matrix , satisfying condition [30]

Now further G(x) in terms of elementary functions is constructed.

5. Fundamental Solution of System of Equation of Steady Oscillations

Lemma 2. The matrix Y defined above is the fundamental matrix of operator Θ(Δ); that is,

Proof. To prove the lemma, it is proved that

The following matrix is now introduced:

Hence, the following theorem has been proved.

6. Basic Properties of the Matrix G(x)

Property 1. Each column of the matrix G(x) is the solution of the system of (22) at every point x ∈ E3 except the origin.

Property 2. The matrix G(x) can be written as

7. Numerical Results and Discussion

The following values of relevant parameters for numerical computations are taken.

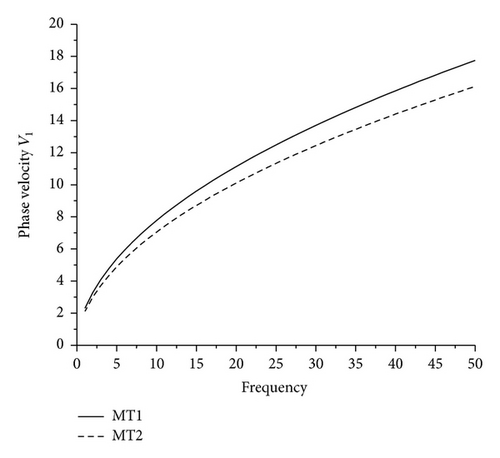

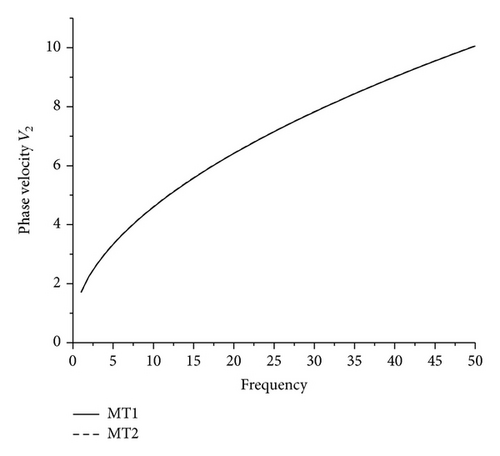

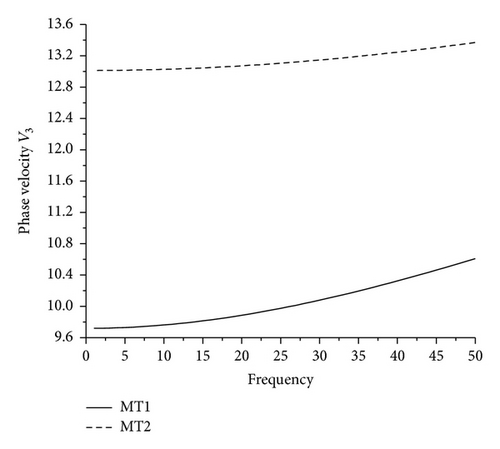

7.1. Phase Velocity

It is noticed from Figures 1–4 that the magnitudes of the phase velocities Vi, i = 1,2, 3,4, for MT1 and MT2 increase with increase in frequency. The phase velocity V1 for MT1 is greater than the phase velocity for MT2, while for V2, V3, V4 the behavior is reversed. This shows that as the value of micropolar constant increases, the phase velocity V1 decreases, while other phase velocities increase. There is slight difference in the phase velocity V2 for MT1 and MT2.

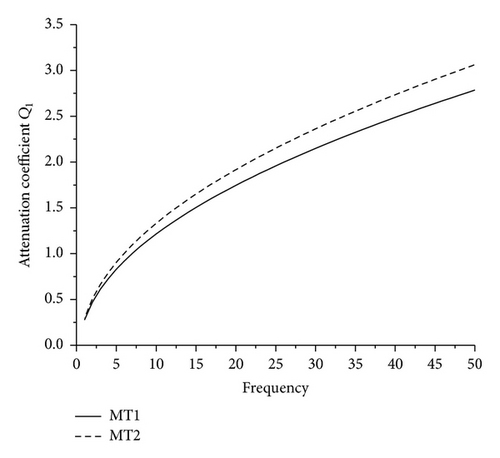

7.2. Attenuation Coefficient

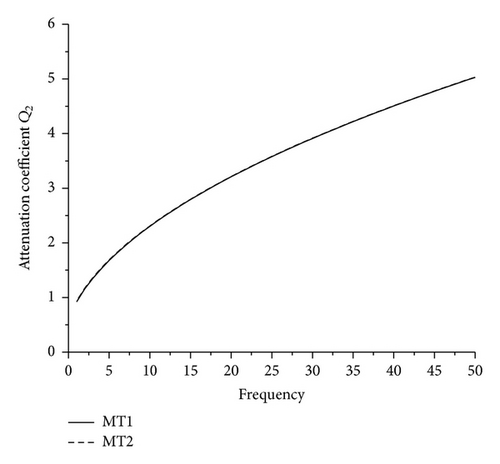

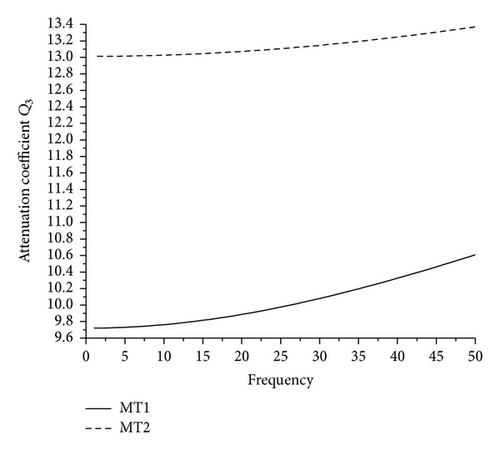

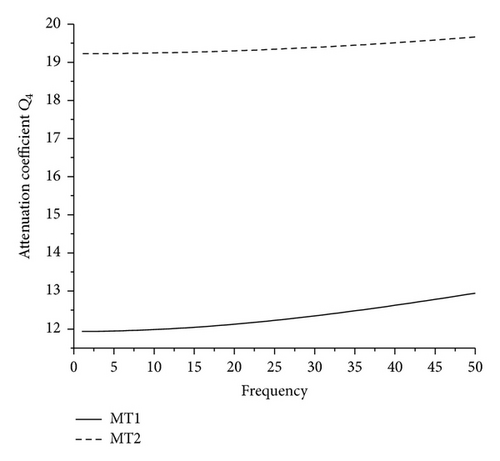

Figures 5–8 depict that the magnitudes of attenuation coefficient Qi, i = 1,2, 3,4, get increased with increase in wave number ω. It is noticed that, with increase in the value of K, the magnitude of attenuation coefficient increases; that is, the values of attenuation coefficients for MT2 are greater than the values for MT1 that shows the effect of micropolarity.

8. Conclusion

In the present paper, we have studied the propagation of plane waves in heat conducting micropolar fluid. The magnitudes of phase velocities and attenuation coefficients are depicted numerically and presented graphically with respect to frequency. Appreciable micropolarity effect is observed on these amplitudes. It is noticed that the magnitudes of phase velocity Vi, i = 2,3, 4, and attenuation coefficient Qi, i = 1,2, 3,4, for K = 0.4 remain more than the magnitude for K = 0.2. This reveals that the more the value of micropolar constant, the more the magnitude of phase velocity and attenuation coefficient. The fundamental solution in heat conducting micropolar fluid in case of steady oscillations in terms of elementary functions is also constructed in the present study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.