Optimal Capacity Allocation of Large-Scale Wind-PV-Battery Units

Abstract

An optimal capacity allocation of large-scale wind-photovoltaic- (PV-) battery units was proposed. First, an output power model was established according to meteorological conditions. Then, a wind-PV-battery unit was connected to the power grid as a power-generation unit with a rated capacity under a fixed coordinated operation strategy. Second, the utilization rate of renewable energy sources and maximum wind-PV complementation was considered and the objective function of full life cycle-net present cost (NPC) was calculated through hybrid iteration/adaptive hybrid genetic algorithm (HIAGA). The optimal capacity ratio among wind generator, PV array, and battery device also was calculated simultaneously. A simulation was conducted based on the wind-PV-battery unit in Zhangbei, China. Results showed that a wind-PV-battery unit could effectively minimize the NPC of power-generation units under a stable grid-connected operation. Finally, the sensitivity analysis of the wind-PV-battery unit demonstrated that the optimization result was closely related to potential wind-solar resources and government support. Regions with rich wind resources and a reasonable government energy policy could improve the economic efficiency of their power-generation units.

1. Introduction

Wind and solar energy are forms of green energy with tremendous application prospects. At present, some countries have started research on the key technical problems of wind-photovoltaic- (PV-) battery units [1–4]. In 2011, China established a demonstration wind-PV-battery unit in Zhangbei; this project aims to explore the stability and economic efficiency of large-scale power grids with renewable energy sources [5].

Numerous studies on optimizing the capacity of wind-PV-battery units have been reported. These studies can be mainly divided into single and multiple objective optimizations. The former primarily considers power distribution reliability as a constraint and targets minimum investment cost. For example, aiming to reduce net present cost of distribution systems, Mohammadi et al. suggested using particle swarm optimization to optimize the capacities of distributed generators in a microgrid under different market policies [6]. To minimize the annual cost of a system, Yang et al. considered the expected power shortage rate as a constraint and established an independent capacity optimization model for wind-PV-battery units. He applied the model in a communication relay station in the southeastern coastal areas in China and thus confirmed the feasibility of his model [7–9]. Diaf et al. established an independent economic optimization model for wind-PV-battery units to minimize the levelized cost of energy (LCE) and to analyze the sensitivity factors of wind-PV-battery units [10].

Multiple objective optimizations mainly aim to improve investment cost and power distribution reliability. Moreover, they consider environmental protection, such as reducing exhaust emissions. For example, Kazem and Khatib calculated the optimal capacity ratio of a wind-PV-diesel-battery power-generation system through a numerical algorithm to minimize cost and maximize power distribution reliability. They verified the economic efficiency and feasibility of their optimal capacity ratio through the power supply system in several communities in Oman [11]. Aiming at a minimum life cycle cost with no load shedding, Li et al. used a simple sizing algorithm to calculate the capacity allocation of an independent wind-PV-battery unit and determined that the state of charge (SOC) of a battery should be periodically invariant. They confirmed the reliability and economic efficiency of the algorithm through a case study in Zhoushan Island, China [12]. To minimize the LCE and CO2 emissions within equivalent life cycles, Dufo-López et al. adopted a multiobjective evolutionary algorithm to calculate the optimal capacity ratio of a wind-PV-diesel-battery power-generation system [13, 14]. To minimize system cost and loss of power supply probability, Khatiba et al. calculated the optimal capacity ratio of a wind-PV-battery unit in a microgrid environment by using a genetic algorithm (GA). Moreover, they further optimized the hub height of a wind turbine and the optimal tilt angle of the PV array [15].

Previous studies on the capacity allocation of wind-PV-battery units have mainly focused on allocating appropriate wind-PV capacity ratios to achieve a wind-PV output power that is as close as possible to the load curve as well as to reduce charge-discharge times and the discharge depth of the battery. The capacity allocation and characteristics of the overall output power are closely related to the load variation trend, thus significantly restricting its application in large-scale wind-PV-battery units. During the grid-connected operation of a large-scale wind-PV-battery unit, the power grid has to consider the unit as a power plant with a particular rated capacity to perform corresponding dispatcher tasks. In the present study, an optimal capacity allocation of wind-PV-battery units based on a rate capacity was proposed to minimize the net present cost (NPC). The optimal capacity of each wind-PV-battery unit under a rated capacity was calculated by using a HIAGA.

2. Operating Model of the Wind-PV-Battery Units

2.1. System Structure

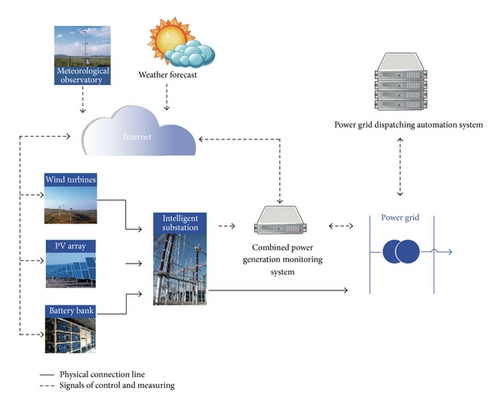

The wind-PV-battery units mainly consist of a combined power-generation monitoring system, a wind generator, a PV array, and a battery-energy storage device. The basic structure is shown in Figure 1.

The wind generator and the PV array are primarily responsible for generating power from renewable energy sources such as wind and solar energy, whereas the battery is responsible for maintaining a stable overall power output of the wind-PV-battery units through peak clipping and valley filling. The combined power-generation monitoring system provides a reasonable arrangement of the power-generation devices according to dispatching commands and weather forecasts (e.g., wind speed, illumination intensity, and temperature), thus ensuring the stable grid-connected operation of the wind-PV-battery units.

2.2. Output Power Model of the Wind Generator

2.3. Output Power Model of the PV Module

2.4. Battery Model

- (1)

charge

() - (2)

discharge

()

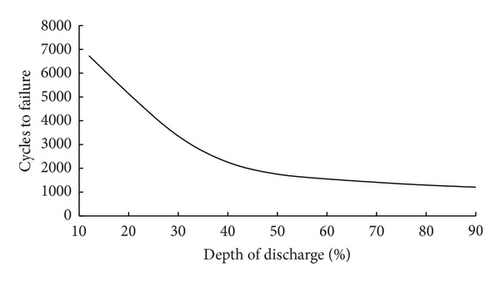

The modeling of the life cycle of a battery will affect the calculation of total system cost. Existing literature has established the life cycle expectancy model of batteries based on battery operations and charge-discharge strategies under a constant temperature [18]. The present study adopts the method of Lopez [11] which estimates cycles to failure of batteries by calculating the number of charge and discharge within an interval of several discharge depths (Figure 3).

3. Optimization Model

3.1. Coordinated Operating Strategy

The wind-PV-battery unit controls the battery device through the principle of maximum utilization of renewable energy sources and constant output power. When the wind-PV output power is smaller than the dispatching demand (Pref), the remaining power is replenished through battery discharge. Battery devices stop active output power until they reach the maximum discharge depth (Socmin).

When the wind-PV output power is higher than Pref, surplus energy is stored in the battery. Battery devices stop charging when they are fully charged (Socmax).

3.2. Optimization Variables

3.3. Objective Function

The reliable and high-quality electric power supply with renewable energy sources, optimal environmental protection, and maximum economic benefits are the development goals of new-energy power enterprises. The goals of the optimal capacity allocation of large-scale wind-PV-battery power-generation unit designed in this paper include minimum total investment cost, maximum utilization rate of renewable energy sources, minimum environmental cost, maximum power distribution reliability.

3.4. Performance Constraints

(3) Wind-PV Complementary Constraint. The overall output power can be kept stable, and the number of charge-discharge as well as the discharge depth of the battery devices can be reduced by applying wind-PV complementation.

4. The Hybrid Iteration/Adaptive Genetic Algorithm

4.1. Basic Idea of the Algorithm

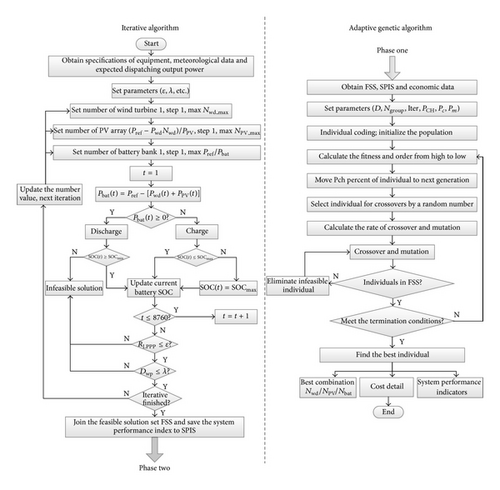

The optimal capacity allocation of large-scale wind-PV-battery unit was solved through iteration/adaptive hybrid genetic algorithm. This algorithm is divided into 2 stages as follows.

Stage 1. On the basis of the specification parameters of equipment, meteorological conditions, and expected dispatching output power and taking formulas (1)–(11) as the constraints of the equipment and formulas (15)–(17) as the constraints of the global performance, the iteration method was adopted to calculate the feasible solutions and feasible solution set PSS satisfying the system performance indexes.

Stage 2. On the basis of the elements and economic parameters in PSS and taking formulas (13)-(14) as objective function, adaptive genetic algorithm was utilized to solve the optimal capacity allocation result from PSS.

4.2. Improved Adaptive Genetic Algorithm

Genetic algorithm was firstly proposed by Professor Holland in University of Michigan in 1975 [21]. This algorithm searches for an optimal solution by simulating the natural evolutionary process which can offset nondifferentiation and discontinuity of functions. In consideration of abundant variables, a discontinuous variable domain of definition, multiple constraints, and other characteristics of the optimal capacity allocation model of wind-PV-battery unit, genetic algorithm owns obvious advantage to solve its optimal capacity allocation issue. However, a lot of studies and practices have demonstrated that the traditional genetic algorithm has poor local search capacity, premature convergence, and other defects. To solve the above problems, Srinivas and Patnaik proposed adaptive genetic algorithm which could dynamically adjust crossover probability pC and mutation probability pM according to the changes of fitness [22]. This paper adopted hybrid iterative/genetic algorithm from Khatib et al. [15] and Neungmatcha et al. fuzzy logic control method to dynamically adjust pC and pM and improve from group initialization, selection, crossover, mutation, and other aspects [23]. In this way, the convergence rate can be speeded up, the search efficiency can be optimized, and further the locally optimal solution can be avoided.

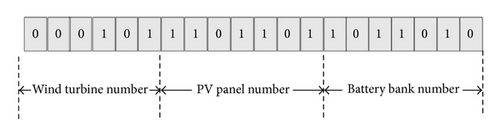

(1) Individual Coding. Binary coding was used to express three optimization variables, the numbers of wind generators, PV modules, and batteries. The lengths of these three optimization variables can be determined according to the constraints, which will be connected together to form an integral Lwpb long binary coding, shown as in Figure 4.

(2) Generation of Initial Group. Guaranteeing the variety of initial group contributes to the search of the whole solution space of the algorithm and avoids the premature convergence. This paper adopted the absolute Hamming distance H(xi, xj) between different individuals as the measurement of group in the individual distribution and the Hamming distance between all the individuals in the group was required H(xi, xj) (i, j = 1,2, …, Lwpb, i ≠ j) ≥ D. At this time, the group size NGroup with individual length of Lwpb was noted as 2Lwpb − D + 1. Distance D was determined by the complexity of the issue and generally it fell approximately between 30 and 200.

(3) Selection Strategy. Selection, crossover, mutation, and other random operations may destroy the optimal individual in the current group which may have adverse effects on the operating efficiency and convergence. This paper utilized the elitist retention mechanism to keep the individuals with stronger fitness to the next group. At the same time, there was common competition between the parent group and offspring group and they were ordered from stronger fitness to poor ones. The high-quality individuals in the former proportion of PCH can be directly copied to the next generation.

4.3. Steps of the Algorithm

Stage 1

Step 1. Obtain meteorological data, specifications of equipment, and system expected output power data. Set the value range of optimization variables to reduce the cycle times of iterative algorithm. Among them, the lower limit of wind unit and PV unit is set as 1 while their upper limit is constrained by the planned site and PwdNwd + PPVNPV > Pref. The lower limit of the number of batteries is set as 1 and its upper limit is set as Pref/Pbat.

Step 2. Preset ε, λ and calculate each capacity combination to obtain the feasible solutions satisfying the constraints. Also, the system performance indexes of each group are gathered, for example, service hours of wind generator, gross generation, charge-discharge times of battery, and loss of power supply probability.

Stage 2

Step 1. Obtain feasible solution set, corresponding system performance indexes, and economic parameters. Code each set of feasible solutions according to Figure 4 and set the minimum group Hamming distance as D. Obtain the initial values of the group size (NGroup), the number of iterations (Iter), proportion of high-quality individuals (PCH), crossover probability (pC), and mutation probability (pM). The initial group (G) is gained.

Step 2. According to formulas (13)-(14), calculate the economic efficiency of individual capacity allocation plan. In consideration of the energy waste and wind-PV complementation, the individual fitness is calculated according to formula (19).

One has

According to the selection strategy and crossover and mutation strategy in Section 4.2, the group is updated and Gi is got.

Step 3. Judge whether the terminal condition of the algorithm is satisfied. If not, turn to Step 2. If so, select the individual GIter with the strongest fitness and output capacity allocation plan and costs of each unit as well as the overall performance index of the system. The procedure of the algorithm was shown in Figure 5.

5. Case Study

5.1. Basic Data

A simulation calculation was conducted in Zhangbei county, Zhangjiakou city, Hebei province. Zhangbei is located in 114°21′E to 114°27′E, 40°59′N to 41°07′N, and meteorological condition data in 2003 were used. The expected constant dispatching output power was set as Pref = 100 MW and the specification parameters of equipment, economic parameters, and algorithm parameters were shown as in Tables 1, 2, and 3. PV panels of the same type are connected to the independent inverter chamber to form PV unit. Battery energy storage unit is formed by connecting several battery cabinets into a battery pack series and then connecting other battery pack series in parallel. The division of PV unit and energy storage unit is good for the operators’ control of the large-scale power generation unit.

| Wind generator | PV module | Battery | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| Serial no. | GW2000A | Serial no. | STP300 | Model no. | KYN61 |

| Rated power (MW) | 2.0 | Peak power (MWp) | 0.5 | Rated capacity (MW·h) | 1 |

| Cut-in wind speed (m/s) | 4.3 | Open-circuit voltage (V) | 44.6 | Maximum charge depth (%) | 70 |

| Rated wind speed (m/s) | 10.8 | Short-circuit current (A) | 8.33 | Charge efficiency (%) | 90 |

| Cut-out wind speed (m/s) | 25.6 | Size (mm) | 1966 × 982 × 50 | Nominal voltage (KV) | 40.5 |

| Hub height (m) | 80 | Peak temperature coefficient (°C) | −0.47% | Maximum power (MW) | 1 |

| Equipment no. | Price (US$) | Operating maintenance cost (US$/Y) | Downtime maintenance cost (US$/Y) | Feed-in tariff (US$/KW·h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW2000A | 1,370,000 | 6,000 | 4,000 | 0.14 |

| STP300 | 750,000 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.19 |

| KYN61 | 950,000 | 8,000 | 1,600 | 0.11 |

| Index | Parameter value |

|---|---|

| Iter | 60 |

| NGroup (Lwpb) | 30~200 |

| PCH (%) | 5 |

| λ | 1.5 |

| ε (%) | 10 |

| λ1 | 5 × 108 |

| λ2 | 2 × 108 |

5.2. Optimization Results and Analysis

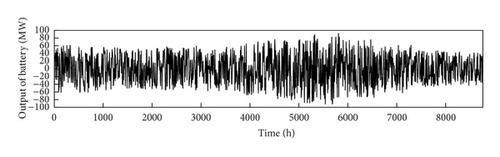

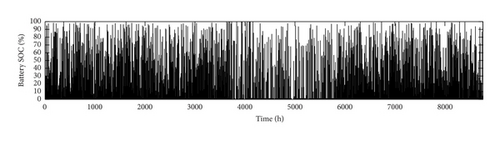

(1) The Optimization Results Analysis. A simulation was conducted based on the proposed optimal capacity allocation. The final optimization results are shown in Figures 6 to 8.

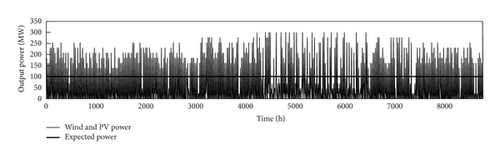

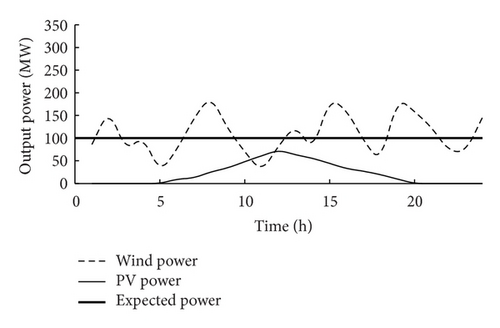

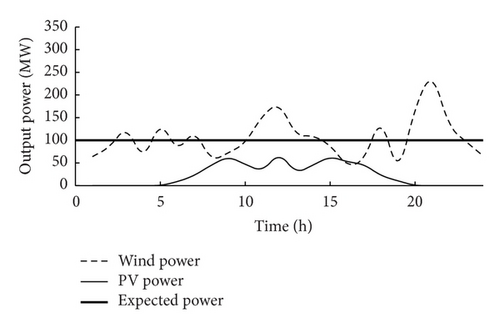

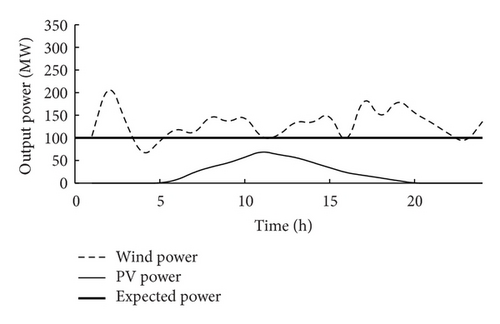

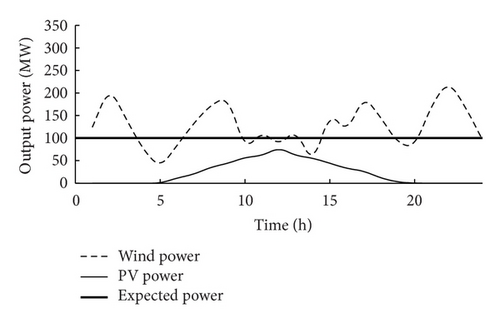

Figure 6 presents the wind-PV output power curve and the overall output power curve of the wind-PV-battery unit in a year. Under a fixed coordinated operation and control strategy, the wind-PV-battery unit can output constant power at any time, thus ensuring stable grid-connected operation of renewable energy sources. Table 4 lists the optimal capacity allocation: 242 MW for the wind generator, 81 MW for the PV module, and 72 MW for the battery, thus showing a ratio of 0.61 : 0.21 : 0.18. Based on these values, the wind generator has a relatively higher installed capacity compared with the PV module and the battery. The local output power curve of the wind-PV-battery unit (Figure 7) explores the reason for the higher installed capacity of the wind generator in Zhangbei county. Zhangbei county has rich and even wind resources throughout the year, thus resulting in strong matching between the output power of the wind generator and the expected dispatching demand. Solar resources have less dispatching demand because they are only available during daytime. In particular, during the summer rainy season sunlight time shortens but temperature increases, thus significantly decreasing the energy conversion efficiency of PV modules and decreasing PV output.

| Optimizer | Wind turbine | PV unit | Battery unit | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Capacity (MW) | Number | Capacity (MW) | Number | Capacity (MW) | Ratio | Cost (US$) | |

| Hocaoglu | 129 | 258 | 144 | 72 | 70 | 70 | 0.65 : 0.18 : 0.17 | 351,230,000 |

| Proposed | 121 | 242 | 162 | 81 | 72 | 72 | 0.61 : 0.21 : 0.18 | 355,670,000 |

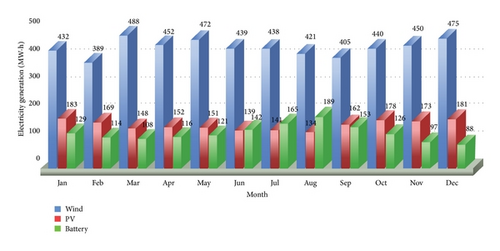

According to the comparison of electricity generation (Figure 8), wind is the major source of electricity generation and PV is used nearly equally throughout the year, whereas battery is mainly used during summer. Further analysis (Figures 9-10) demonstrates frequent battery charge-discharge from June to August because weather changes often during the rainy season. Consequently, the wind-PV output fluctuates violently, thus requiring the battery to charge and discharge frequently to smooth power fluctuation and to ensure the constant output of the wind-PV-battery unit.

(2) Contrastive Analysis with Hocaoglu Optimization Algorithm [24]. The capacity allocation results under the condition of 100 MW expected output power of the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper and Hocaoglu optimization algorithm are shown as Table 4. It can be seen from the comparative results that the installed capacity of wind unit allocated by Hocaoglu optimization algorithm was higher than those of PV and battery units. The reason is that, in Hocaoglu optimization computation process, the model of battery life cycle was not established. Instead, it was simplified into a replacement every 5 years. Furthermore, this method did not consider the influence of wind-PV power output fluctuation range on the life cycle of battery. This kind of allocation had a lower initial investment cost while the accuracy degree of the model was poorer. As seen from the total investment cost in Table 4, compared with the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper, Hocaoglu optimization algorithm decreased 1.2% but its total investment cost of the entire project term may not be optimal. Table 5 provides the costs of each unit through simulation calculation on the basis of 2003–2013 meteorological data. It can be seen from the cost details in Table 5 that the initial investment and construction year was 2003. Thus, the costs of both algorithms in 2003 were high and the costs left years were constituted of operation costs and replacement costs. Every 5 years, there was one peak in cost for Hocaoglu optimization algorithm which was related to the 5-year life cycle of battery. The annual expense of the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper was average and there was no large-scale battery replacement. During the allocation process, this method fully considered wind-PV complementation, which contributed to decreasing the wind-PV output fluctuation range and frequency, the charge-discharge times, and discharge depth of battery, which could extend the life cycle of battery and minimize the total cost in the whole life cycle. From the aggregated data in the last line of Table 5, it can be seen that the total costs of the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper were 397,185,800 (US.$), 1.2%, lower than that of Hocaoglu optimization algorithm. Its NPC was 264,973,700 (US.$), decreasing by 2%.

| Year | Hocaoglu | Proposed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expense (US$) | Income (US$) | NPC (US$) | Expense (US$) | Income (US$) | NPC (US$) | |

| 2003 | 360,369,200 | 12,210,800 | 331,579,400 | 364,809,200 | 12,755,100 | 335,289,600 |

| 2004 | 3,846,600 | 11,780,100 | −7,195,900 | 3,380,800 | 13,483,300 | −9,163,265 |

| 2005 | 2,532,500 | 13,283,900 | −9,287,400 | 2,979,000 | 12,869,600 | −8,543,800 |

| 2006 | 2,332,600 | 13,344,700 | −9,059,600 | 4,021,500 | 12,719,300 | −7,155,700 |

| 2007 | 9,687,600 | 12,424,100 | −2,144,100 | 3,994,000 | 11,925,700 | −6,214,600 |

| 2008 | 2,019,500 | 11,699,800 | −7,223,500 | 2,461,800 | 12,691,600 | −7,633,600 |

| 2009 | 3,464,900 | 12,710,000 | −6,570,300 | 3,459,100 | 13,150,900 | −6,887,700 |

| 2010 | 3,450,700 | 13,256,800 | −6,637,100 | 4,017,300 | 13,090,200 | −6,140,800 |

| 2011 | 2,702,300 | 11,858,600 | −5,902,200 | 2,511,100 | 13,370,200 | −6,999,800 |

| 2012 | 9,457,500 | 11,795,300 | −1,435,200 | 2,998,500 | 11,809,400 | −5,409,100 |

| 2013 | 2,031,000 | 11,920,000 | −5,781,800 | 2,553,500 | 13,101,200 | −6,167,000 |

| Total | 401,894,400 | 136,284,100 | 270,341,800 | 397,185,800 | 140,966,500 | 264,973,700 |

Table 6 shows the system performance indexes through simulation calculation on the basis of 2003–2013 meteorological data. It is found that each index of the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper was superior to that of Hocaoglu optimization algorithm. Among them, loss of power supply probability was 6.57%, decreasing by 21.4%; wind-PV complementation was 1.22, increasing by 11.6%; charge-discharge times of battery were 676,548, decreasing by 7.5%; levelized cost of energy was 0.215 (US$/KW·h), decreasing by 3.6%.

| Indicator | Hocaoglu | Proposed |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of produced power probability (%) | 8.36 | 6.57 |

| Wind-PV complementation characteristics | 1.38 | 1.22 |

| Number of battery charge-discharge | 730,997 | 676,548 |

| LCE (US$/KW·h) | 0.223 | 0.215 |

(3) Convergence Analysis of the Algorithm. To make an objective and overall evaluation of the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper, Hocaoglu optimization algorithm, Khatib optimization algorithm [15], and the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper, respectively, carried out 30 simulations. Through the changes of the parameters of the algorithm, the group number and CPU computation time at the beginning of convergence were observed and gathered (shown as in Table 7). It can be seen that HIAGA optimization algorithm was the fastest and started convergence at 22nd-generation group and its average convergence algebra was 27.6, respectively, 30.5% and 20% higher than Hocaoglu optimization algorithm and Khatib optimization algorithm. In terms of CPU computation time, the average convergence time of HIAGA optimization algorithm was 85.8 s, respectively, 10.6% and 6.4% higher than Hocaoglu optimization algorithm and Khatib optimization algorithm. These indicated that the convergence rate of HIAGA optimization algorithm was faster and it owned certain advantages compared with the previous research results.

| Optimizer | Convergence at generation k | CPU times of convergence(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Average | Minimum | Maximum | Average | |

| Hocaoglu | 28 | 54 | 39.7 | 92.3 | 116.1 | 96.0 |

| Khatib | 29 | 39 | 34.5 | 86.9 | 114.6 | 91.7 |

| Proposed | 22 | 31 | 27.6 | 82.1 | 94.3 | 85.8 |

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

(1) Potential Wind-PV Resources. Through simulations in several regions in China, the optimal capacity allocation and costs of each component of the wind-PV-battery unit, when Pref = 100 MW were calculated as shown in Table 8, and large-scale wind-PV-battery units in regions with rich wind resources have high economic efficiency because wind-dominated units require less capacity for cost-ineffective battery (high cost but short life cycle) compared with PV-dominated units. Furthermore, the even distribution of wind power and appropriate PV output complementation enable the entire wind-PV-battery unit to maintain a constant output with only a small battery capacity.

| Region | Annual average wind speed (m/s) | Annual average illumination intensity (W/m2) | Annual average temperature (°C) | Capacity allocation (Nwd/NPV/Nbat) | NPC (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhangbei | 6.6 | 1040 | 2.6 | 121/2.7 × 105/72 | 188,274,000 |

| Chifeng | 6.1 | 980 | 1.9 | 126/2.95 × 105/82 | 197,463,000 |

| Tangshan | 3.6 | 1270 | 5.8 | 82/5.94 × 105/172 | 422,198,000 |

| Datong | 4.1 | 1210 | 2.9 | 95/5.31 × 105/156 | 387,579,000 |

| Baotou | 6.4 | 1025 | 2.2 | 82/2.95 × 105/82 | 195,387,000 |

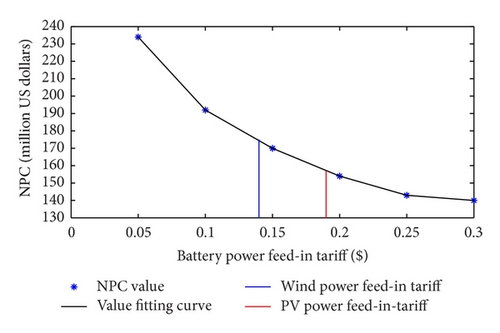

(2) Government Support. China is experiencing an increasing number of hazy days because of the continuously worsening environment. Consequently, the country is paying significant attention to the development of green energies. However, wind-PV-battery power generation is inferior to thermal power generation because of its lower economic efficiency. As such, the government should formulate reasonable energy policies to support the development of new energy-based power enterprises. At present, numerous countries worldwide support wind power and PV power generation. China also adopted a fixed electricity price and increased subsidies to PV power generation in 2008. However, no policy about the feed-in tariff of battery power has yet been released. The relationship curve between the feed-in tariff of battery power and the NPC of the wind-PV-battery unit is presented in Figure 11.

According to Figure 11, the NPC of the wind-PV-battery unit is more sensitive to the feed-in tariff of battery power when the latter is smaller than the feed-in tariffs of wind power and PV power. This finding is attributed to the low economic efficiency of battery power. Moreover, each charge-discharge requires high investment costs, thus significantly affecting the NPC. When the feed-in tariff of battery power exceeds those of wind power and PV power, the optimal capacity allocation will involve an extremely large proportion of battery energy to absorb all wind-PV electricity, thus influencing the NPC slightly. However, this process violates the practical significance of the wind-PV-battery unit.

6. Conclusion

This study proposes an optimal capacity allocation of a large-scale wind-PV-battery unit, in which the wind-PV-battery power-generation system is connected to the power grid as a power-generating unit with a fixed rated capacity. This feature does not only ensure the stable output of the wind-PV-battery unit, but is also convenient to the power grid for evaluating the power-generation capacity of the wind-PV-battery unit, thus formulating a corresponding dispatching plan and increasing acceptance of renewable energy sources. Aiming at minimum NPC and considering power distribution reliability, energy utilization rate, and other indexes, the iteration/adaptive hybrid genetic algorithm was used to solve the optimal capacity ratio of each component in the wind-PV-battery unit and a simulation analysis on the wind-PV-battery unit with a construction rated capacity of 100 MW in Zhangbei county (China) was carried out. Then the comparative results between Hocaoglu optimization algorithm and HIAGA optimization algorithm indicated that HIAGA optimization algorithm could minimize the investment cost of the entire life cycle of the power-generation unit project and the accuracy and validity of the model and algorithm were also verified. Through the multiple simulation calculations, the optimization algorithm proposed in this paper owned faster convergence rate and search efficiency than Hocaoglu and Khatib optimization algorithm. Finally, the sensitivity analysis of the large-scale wind-PV-battery unit determines that wind-solar resources and government energy policies have a significant effect on the economic efficiency of the unit. The wind-PV-battery unit in regions with rich wind resources requires less battery capacity compared with that in regions with rich solar resources, thus exhibiting higher economic efficiency. A reasonable feed-in tariff for battery power imposed by the government can improve the economic benefits of new energy-based power enterprises. The results of the sensitivity analysis also confirm the accuracy of the proposed model and algorithm.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the State Key Laboratory of Alternate Electrical Power System with Renewable Energy Sources (North China Electric Power University).