Biochemical Engineering Parameters for Hydrometallurgical Processes: Steps towards a Deeper Understanding

Abstract

Increasing interest in biomining process and the demand for better performance of the process has led to a new insight toward the mining technologies. From an engineering point of view, the complex network of biochemical reactions encompassed in biomining would best be performed in reactors which allow a good control of the significant variables, resulting in a better performance. The subprocesses are in equilibrium when the rate of particular metal ion; for example, iron turnover between the mineral and the bacteria, is balanced. The primary focus is directed towards improved bioprocess kinetics of the first two subprocesses of chemical reaction of the metal ion with the mineral and later bacterial oxidation. These subprocesses are linked by the redox potential and controlled by maintenance of an adequate solids suspension, dilution rate, and uniform mixing which are optimised in bioreactors during mining operations. Rate equations based on redox potential such as ferric/ferrous-iron ratio have been used to describe the kinetics of these subprocesses. This paper reviews the basis of process design for biomining process with emphasis on engineering parameters. It is concluded that the better understanding of these engineering parameters will make biomining processes more robust and further help in establishing it as a promising and economically feasible option over other hydrometallurgical processes worldwide.

1. Introduction

Biomining is gaining importance as a unit process which involves biological organisms in mineral extraction industries worldwide. With the decreasing high grade ore reserves and increased concern regarding the effect of mining on the environment, biomining technology, which was nevertheless age old deserted technique, is now being developed as a main process in the mining industry to meet the demand [1]. Another important aspect is the feasibility of biomining technologies to treat ores deposits with complex mineralogy, which could be difficult to treat by conventional methods [2]. Besides, the most attractive feature of biomining is economic feasibility compared to other competitive techniques [2]. Gahan et al. [2] comparatively analysed how gold and copper biomining operations played a role with the increase or decrease in metal pricing over time. Their analysis indicated that most biohydrometallurgical innovations have been commercially implemented during leaner times [3]. Economic factors such as eliminations of net Smelter Royalties associated with smelting and refining and possibility of the use bioleaching for on-site acid production to eliminate or reduce acid purchases are the reasons behind this observation. This has made us look toward the biomining with a broader insight into performance and profit oriented research to meet the commercial requirements. For this purpose, the process stoichiometry, kinetics, and the key parameters involved in the process have been studied [4–7] and the promising concepts like design and control of reactors for mining operations are yet to be practised [8].

Biomining in general is used to describe the exploitation of chemolithotrophic microorganisms to assist the extraction of metals from sulphide or iron-containing ores or concentrates [9, 10]. It is a combination of two major operations bioleaching and biooxidation. The metal-solubilisation process is a blend of microbiology and chemistry. Knowledge in microbiology is required as specific microorganisms are responsible for producing the ferric iron and acid leading biooxidation; while strong base on chemistry is equally necessary since the solubilisation of the metal is a result of the action of ferric iron and/or acid on the mineral further known as bioleaching [6, 11, 12]. Conventional biomining is usually performed in heaps of ground ore or in the dumps of waste or spent material. Though this process offers several advantages such as simple equipment and operation, low investment, operational costs, and acceptable yields, it is beset with severe operational limitations, such as high heterogeneity of piled material and practically no close process control. Moreover, the low oxygen and carbon dioxide transfer rate and extended periods of operation to achieve sufficient conversions are very challenging [8]. From the process engineering point of view, bioreactors are the best choice for regulating the complex network of biochemical reactions comprehended in biomining as they allow for a close control of the variables involved, rendering significantly better performances. The reactors are usually arranged in series, with a continuous flow of material into the first, which overflows to the next, and so on for reduction of reaction volume required [13]. Therefore, process designing approach along with the defined application and monitoring of the abundance and activity of the metal sulfide oxidizing microorganisms will make the biomining process more industrially popular and as a portfolio of flexible techniques to provide a way of recovering metal (Figure 1).

In this paper we discuss many of the theoretical considerations regarding the development of process for application of continuous-flow stirred-tank reactors in biomining with focus on different engineering parameters which should be taken into consideration for better control and design of biomining processes.

2. Mining Mechanisms and Stoichiometry

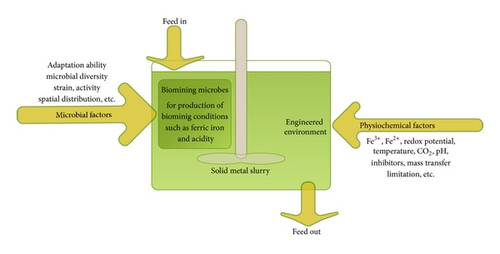

The most important mineral degrading microorganisms in biomining applications are the iron and sulphide oxidizing chemolithotrophs which grow autotrophically by fixation of atmospheric CO2. However, the mineral dissolution mechanism is not the same for all metal sulphides. Schippers and Sand [14] reported that the oxidation of different metal sulphides proceeds via different intermediates: (1) thiosulphate mechanism for the oxidation of acid-insoluble metal sulphides such as pyrite (FeS2) and molybdenite (MoS2) and (2) polysulphide mechanism for acid-soluble metal sulphides such as sphalerite (ZnS), chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), or galena (PbS) (Figure 2) [1].

3. Process Kinetics

4. Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer

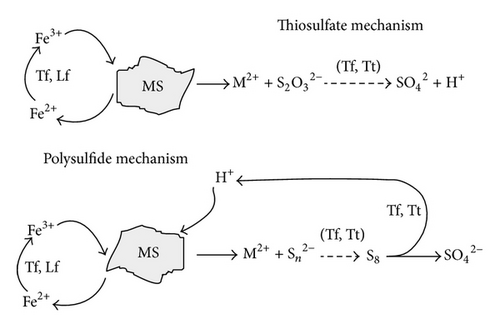

The effects of dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide concentration on microbial activity have been investigated by de Kock et al. [23] considering the microbial activity to be directly proportional to the Fe3+ ion concentration in the medium.

5. Temperature, pH, and Redox Potential

Physical conditions like temperature and pH are the inherent properties of microorganism and so they vary with microorganisms and mainly get decided by the dominant species in the consortium like T. ferrooxidans and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans [24]. The temperature has been shown to be clearly impacting the biomining rate on iron oxidation by mesophilic mixed iron oxidizing microflora [25]. By elevating from 20 to 30°C the rate was reported to increase and beyond this temperature the rate decreased due to denaturation of enzymes and proteins as well as the behaviour of ferric ion. Operating the reactor at higher temperature is advantageous in some cases such as during biooxidation of sulfidic-refractory gold concentrates; it allows growth of thermophilic microorganisms rendering oxidisation of partially oxidised sulfur compounds that are responsible for increasing cyanide consumption [26]. Also, bioleaching of chalcopyrite concentrates has been demonstrated using moderately thermophilic bacteria [27] and extremely thermophilic Archaea [28]. However, operating the reactor in thermophilic range increases both capital and operating costs of the process. Hence, more promising approach is to use a combination of mesophilic/thermophilic process, but such approach requires more developments before practice [3]. Besides temperature, since the bacteria involved in biomining are chemolithotropic and acidophilic in character, the optimisation of pH is needed for its growth. The major reason for the dominance of species such as “Leptospirillum” and T. ferrooxidans in industrial processes is almost certainly the Fe3+/Fe2+ ratio, that is, redox potential (Eh) [14]. To estimate the rate of ferrous iron oxidation throughout the bioleaching process to obtain explicit data of [H+] and [Fe3+] from the values of Eh and pH, a preliminary calibration procedure should be developed. For this purpose, Nernst expressions which relate the solution redox potential with the ferric/ferrous ratio in solution were obtained [17], given as follows.

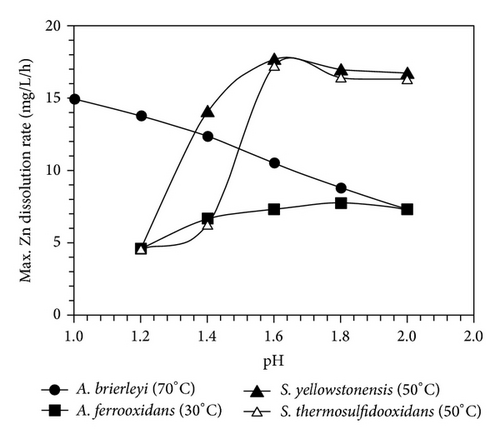

However, there may be many other factors which may contribute to the dominance of particular species in consortia. The optimum pH for the growth of T. ferrooxidans is within the range pH 1.8–2.5, whereas L. ferrooxidans is more acid-resistant than T. ferrooxidans and can grow at a pH of 1-2 [16]. With regard to temperature, T. ferrooxidans is more tolerant of low temperature and less tolerant of high temperature than is L. ferrooxidans. Some strains of T. ferrooxidans are able to oxidize pyrite at temperatures as low as 10°C [30] but 30–35°C is considered to be optimal. Leptospirillum-like bacteria have been reported to have an upper limit of temperature for growth around 45°C with a lower limit of about 20°C [31]. Deveci et al. [32] showed that the bioleaching activity of mesophile A. ferrooxidans, as indicated by the dissolution rate of the zinc, Figure 5, was adversely affected with decreasing pH to ≤1.4. But, above this pH, there seemed no significant difference in the dissolution rate and extent (91–93%) of zinc. In contrast to A. ferrooxidans, the extraction rate of zinc by the extremely thermophilic A. brierleyi (at 70°C) was observed to increase with increasing acidity. In case of thermophilic S. yellowstonensis and S. thermosulfidooxidans the increase in the acidity to pH 1.2–1.4 led to a decrease in the oxidising activity of both strains, indicating the inhibitory effect of increased acidity on the strains [32].

In a bioleaching process, neutralisation is required at different stages. As the microorganisms used in bioleaching processes are chemolithotrophic and acidophilic having optimum activity at low pH, therefore, the addition of neutralising agents is required to maintain the desired pH depending on the reactor configuration. Neutralisation of the acid produced during bioleaching of sulphide minerals is generally practised using limestone. Gahan et al. [33] concluded in their study that considerable savings in operational costs could be obtained by the replacement of lime or limestone with steel slag, without negative impact on bioleaching efficiency.

6. Solid Suspension and Mixing

The reactors which are mostly used in commercial mining plants operating continuously and in biohydrometallurgical laboratories are the stirred tank reactor (STR) and the airlift reactor (ALR) or pneumatic reactor (PR) of the Pachuca type. Aeration in these reactors depends on suspension agitation, and “flooding” may cause some limitations, while very strong agitation may cause cell damage to the extreme [8]. Normally, the stirred suspension flows through a series of pH and temperature-controlled aeration tanks in which the mineral decomposition takes place. Thus maintaining the uniformity of solid-liquid ratio in reactor system, solid suspension is important for efficient biomining. The solid-liquid ratio becomes a very critical parameter in the bioreactor applications as the solids packed density that can be maintained in suspension is limited to 20% in the operation of stirred tank reactors, beyond which the physical and microbial problems occur. The shear force induced by the impellers causes physical damage to the microbial cells and the liquid as well becomes too thick for efficient gas transfer [34]. In biomining, higher mixing characteristics and lower oxygen transfer rates are needed compared to common industrial fermentations. Hence, impellers that generate axial flow patterns are preferable [13]. Among the axial flow type impellers, the hydrofoil design offering several advantages such as good mixing characteristics, low shear, and gas transfer capabilities are most compatible with the biomining processes demands [8, 35]. A disk turbine at the bottom and a propeller at the upper part of the shaft have been proposed to meet higher oxygen demand situations [36].

7. Continuous Process Dilution Rate

8. Microbial Community Structure

Although microbial community structure is not an engineering parameter, it is an integrated part of biomining processes which catalyses the biochemical reaction involved and should be considered properly in process designing approach. For the robust modelling of the system, knowledge regarding microorganisms present should be acquired as each species is kinetically different from the other. Therefore, the simplistic assumption of lack of diversity in the characteristics of the species within the microbial groups may lead to over- or underestimation of the model output when compared to observed data. There have been considerable studies in the last years to understand the biochemistry of iron and sulphur compounds oxidation, bacteria-mineral interactions, and several adaptive responses allowing the microorganisms to survive in a bioleaching environment which has been reviewed by Valenzuela et al. [41]. There are different groups of microorganisms capable of growth in situations which simulate biomining commercial operations [31]. The biology of leaching bacteria becomes more and more complex due to increasing data on 16S rRNA gene sequences as many new species of leaching bacteria have been described and known species have been reclassified [42]. Moreover, it was believed that only mesophilic bacteria play a role in biomining, but the discovery of new genera of moderate and extremely thermophilic bacteria belonging to Sulfolobus, Acidianus, Metallosphaera, and Sulfurisphaera has made the bioleaching process more economically attractive to the industries where coiling used to be a necessary step to operate the reactors at mesophilic temperature [41, 43]. Change in microbial community dynamics during moderately thermophilic bioleaching of chalcopyrite concentrate has been recently studied by Zeng et al. [44] and it was observed that A. caldus was dominant at the early stage while L. ferriphilum predominated at the later stage in a stirred tank reactor. The bioleaching performance of chalcopyrite for various hydraulic residence times (HRTs) was estimated by Xia et al. [45] and they observed that Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans compete for oxidising ferrous iron, leading to large compositional differences in the microbial community structure under different HRTs. It was observed that Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans dominated under the longer HRT (120 h), while Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans was dominant when the HRT was decreased. It has been suggested that for the proper establishment of active biomining consortia, a substantial period of adaptation is necessary as consortia (mesophiles or moderate thermophiles) cannot be assembled “off the shelf” [46].

9. Conclusions and Perspectives

The future of biomining is much demanding and the incorporation of engineering principles in the field will make the process industrially more acceptable. Stirred-tank bioreactors have clearly opened new opportunities for processing in mining industries as it allows better control than conventional technologies leading to superior leaching efficiency and metal recovery. Aeration, temperature, pH, and so forth can be continually adjusted to achieve maximum microbial activity in stirred-tank reactors. Present studies demonstrate that in designing a biomining process, the bioleaching and biooxidation performance, microbial growth kinetics, and other characteristic properties (gas-liquid mass transfer, solid suspension and mixing, and the characteristic dilution rate of a continuous process) should be reasonably well understood. To evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the controlled process in wide-scale metallurgy, it is essential to make predictions of the biomining performance. The performance assessment and prediction based on both equilibrium and dynamic studies will help in the extended process control increasing the commercial viability.

There are several specific needs for more advancement in the commercialisation of biohydrometallurgy. A prolific area for research is a comprehensive study of microbial community structure with rapid, accurate, and simple techniques for monitoring the microbial activity in bioleach/mineral-biooxidation systems which will enable the operators to gain more control on these processes. More advanced research in applied microbiology will throw light in this regard. In most instances, these advancements will help the metallurgical engineers understand the role and specific operational needs for microorganisms and to improve the designing approaches maximizing the system’s efficiency. Another area for development is in reactor engineering such as materials of construction. New materials for high temperature, highly corrosive conditions that are of relatively low cost, would also advance the technology. Such reactors would amplify opportunities to bioleach whole ores. Robust modelling of the relevant parameters and processes including the microbial community dynamics and structure would make biomining more established and economically feasible option over other hydrometallurgical processes worldwide.

Symbols

-

- αM:

-

- Metal recovery

-

- α:

-

- Specific surface area of pyrite (m2 mol−1)

-

- :

-

- Chemical ferrous iron production rate (mol Fe2+ l−1 h−1)

-

- :

-

- Bacterial ferrous iron production rate (mol Fe2+ l−1 h−1)

-

- :

-

- Ferrous iron production rate (mol Fe2+ l−1 h−1)

-

- A:

-

- Kinetic constant in pyrite oxidation (dimensionless)

-

- cR:

-

- Oxygen concentration in static medium layer (mol l−1)

-

- cP:

-

- Oxygen concentration in mineral matrix, (mol l−1)

-

- D0:

-

- Diffusion coefficient (m2 s−1)

-

- Deff:

-

- Diffusion coefficient in surface matrix of membrane (m2 s−1)

-

- :

-

- Area specific ferrous iron production rate (mol Fe2+ m−2 h−1)

-

- :

-

- Maximum area specific ferrous iron utilization rate (mol Fe2+ m−2 h−1)

-

- :

-

- Electrons from the donor transferred to the terminal electron acceptor

-

- :

-

- Electrons from the donor that is used for net cell synthesis

-

- K:

-

- Kinetic constant (dimensionless)

-

- k:

-

- Rate constant

-

- t:

-

- Time of bioleaching (day)

-

- μmax:

-

- Specific growth rate of the bacterial cell (h−1)

-

- F:

-

- Total feed rate (kg h−1)

-

- [Fe2+]:

-

- Ferrous iron concentration (mg l−1)

-

- [Fe3+]:

-

- Ferric iron concentration (mg l−1)

-

- Fr:

-

- Mixing time number

-

- [H+]:

-

- Proton concentration (mg l−1)

-

- H:

-

- Henry’s law constant (mol dm−3 atm−1)

-

- Ks:

-

- Michaelis-Menten constant (mg l−1)

-

- KI:

-

- Ferric iron inhibition constant (no units)

-

- kLa:

-

- Overall gas mass transfer coefficient

-

- Pg:

-

- Substrate partial pressure in gas phase (atm)

-

- Pl:

-

- Substrate partial pressure at equilibrium with the substrate concentration in the bulk liquid phase (atm)

-

- Ntransported:

-

- Gas mass transfer rate per unit volume of reactor (mol·s−1·l−1)

-

- :

-

- Bacterial specific ferrous iron oxidation rate (mol Fe2+(mol C) −1 h−1)

-

- :

-

- Maximum bacterial specific ferrous iron oxidation rate (mol Fe2+(mol C) −1 h−1)

-

- q:

-

- Specific uptake rate (mol cell−1 h−1)

-

- qmax:

-

- Maximal cell-specific oxygen uptake rate (mol cell−1 h−1)

-

- V:

-

- Volume of processing system (l)

-

- VL:

-

- Liquid volume (l)

-

- Voxi:

-

- Specific ferrous iron oxidation rate (mg (hr cell) −1)

-

- Vchem:

-

- Maximum specific ferrous iron oxidation rate non affected by ferric (mg (hr cell) −1)

-

- Vmax:

-

- Maximum specific ferrous iron oxidation rate (mg (hr cell) −1)

-

- X:

-

- Cell density (cells l−1)

-

- Y:

-

- Bacterial growth yield on ferrous iron oxidation (cell mg−1 Fe)

-

- z:

-

- Bottom clearance (m)

-

- D′:

-

- Tank diameter (m)

-

- d:

-

- Impeller diameter (m)

-

- d′:

-

- Impeller spacing (m)

-

- d′′:

-

- Top clearance (m)

-

- B:

-

- Baffle width (m)

-

- l:

-

- Impeller blade length (m)

-

- w:

-

- Impeller blade width (m)

-

- nb:

-

- Number of blades

-

- nimp:

-

- Number of impellers

-

- nbaf:

-

- Number of baffles

-

- N:

-

- Impeller rotation speed (rpm)

-

- G:

-

- Volumetric gas flow rate (m3 h−1)

-

- ρ:

-

- Liquid density (kg m−3)

-

- η:

-

- Liquid kinematic viscosity (Pa·s)

-

- a, b, c, e, f, h, i, j, k, m, n, p, q, r:

-

- Numerical coefficients in (24) and (25)

-

- P:

-

- Power required to drive the agitator (W).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Ministry of Human Resource and Development (MHRD), Delhi, India, for providing financial assistantship during this project.