The Perturbed Dual Risk Model with Constant Interest and a Threshold Dividend Strategy

Abstract

We consider the perturbed dual risk model with constant interest and a threshold dividend strategy. Firstly, we investigate the moment-generation function of the present value of total dividends until ruin. Integrodifferential equations with certain boundary conditions are derived for the present value of total dividends. Furthermore, using techniques of sinc numerical methods, we obtain the approximation results to the expected present value of total dividends. Finally, numerical examples are presented to show the impact of interest on the expected present value of total dividends and the absolute ruin probability.

1. Introduction

In this model, the premium rate should be viewed as an expense rate and claims should be viewed as profits or gains. While not very popular in insurance mathematics, this model has appeared in various literature (see Cramér [3, Section 5.13] and Seal [4, pages 116–119] and Takács [5, pages 152–154]). There were many possible interpretations for this model. For example, we can treat the surplus as the amount of the capital of a business engaged in research and development. The company paid expenses for research, and occasional profit of random amounts (such as the award of a patent or a sudden increase in sales) arises according to a Poisson process. A similar model was used by Bayraktar and Egami [6] to model the capital of a venture capital investment. Another model was an annuity business. The company issues payments continuously to annuitants, while the gross reserve of an annuitant was released as emerging profit when he died. Yang and Zhu [7] generalized the dual model into a regime-switching setting and calculated bounds for ruin probabilities. One of the current topics of interest in insurance mathematics is the problem of maximizing the expected total discounted dividends until ruin, which goes back to de Finetti [8], and it had also been studied by Bühlmann [9, Section 6.4], Gerber [10, Sections 7 and 8], and Gerber [11, Section 10.1]. In Avanzi et al. [1], the authors studied the expected total discounted dividends until ruin for the dual model under the barrier strategy by means of integrodifferential equations. They derived explicit formulas when profits or gains followed an exponential or a mixture of exponential distributions and showed that the optimal value of the dividend barrier under the dual model was independent of the initial surplus. Avanzi and Gerber [2] studied a dual model perturbed by diffusion and discussed how the optimal value of the dividend barrier can be determined. Albrecher et al. [12] studied a dual model that also paid taxes when the surplus was at a running maximum and calculated the expected total discounted dividends before ruin for exponentially distributed profits.

Dividend strategy for insurance risk models was first proposed by de Finetti [8] to reflect more realistically the surplus cash flowed in an insurance portfolio. Various threshold strategies have been studied by many authors, including Gerber and Landry [13], Ng [14], and Lin and Pavlova [15]. Among them, Ng [14] showed that the threshold strategy was optimal when the dividend rate was bounded and the individual claim distribution was exponential. Recently, the threshold dividend strategy has been considered in the class of compound Poisson process perturbed by diffusion and its generalizations; readers may refer to Avanzi and Gerber [2], Gao and Liu [16], Wan [17], and the references therein.

2. Integrodifferential Equations

2.1. Integrodifferential Equations for M(u, y; b)

In the following, we firstly derive the integrodifferential equations satisfied by M0(u, y; b).

Theorem 1. When 0 < u < b,

Proof. When 0 < u < b, consider t > 0 such that the surplus cannot reach level b by time; that is, hδ(u, τ) = erτ(u − (c1/r)) + (c1/r) > 0. By conditioning on the time and amount of first claim, if it occurs by t, and whether the claim causes ruin, one gets

Set W(t) = B(v(t)) for t ≥ 0, i = 1,2. By the time change of Brownian motion, we have that Wi is local standard Brownian motion with Wi(0) = 0 running for an amount of time σ2/2r.

Let and . Then, we have the following results.

Theorem 2. When 0 < u < b,

Proof. For 0 < u < b, assume that ϵ, t > 0 such that ϵ < u < b. Define and . We have P(T0 < ∞) = 1 for all s ∈ (0, T0). Then, by the strong Markov property, we get

Similarly, using the above method, we get (21). Conditions (22) and (23) are obvious. By (14) and (15) and by the weak convergence method used in [17], it is easy to check that the boundary conditions (24) and (25) hold. This ends the proof of Theorem 2.

2.2. Integrodifferential Equations for V(u, b)

Theorem 3. When 0 < u < b,

3. Numerical Analysis

The second order system of integrodifferential equations such as in Theorem 3 does not have an explicit solution except in some special cases. In this section, we propose the approximate solution of this equation via the use of a collocation based on sinc methods. The sinc method is highly efficient numerical method developed by Frank Stenger. It is widely used in various fields of numerical analysis such as interpolation, quadrature, approximation of transforms, and solution of integral, ordinary differential, and partial differential equations. An introduction to the sinc approximation theory can be found in the Appendix.

3.1. Numerical Solution of the Expected Present Value of Total Dividends V(u; b)

Since , by Theorem A.3 in the Appendix, then it is convenient to take wj = γj = S(j, h)∘ϕ, j = −M, …, N. Moreover, by some simple calculations, we have , j, k = −M, …, N with ϕ and uk being defined in (33) and (41), respectively.

4. Numerical Example

In this section, we consider some numerical samples to illustrate the performance of sinc method and investigate how much the values of V(u; b) are affected by interest r. An example is solved under the assumption that the claim size density is given by f(y) = ηe−ηyI (y > 0).

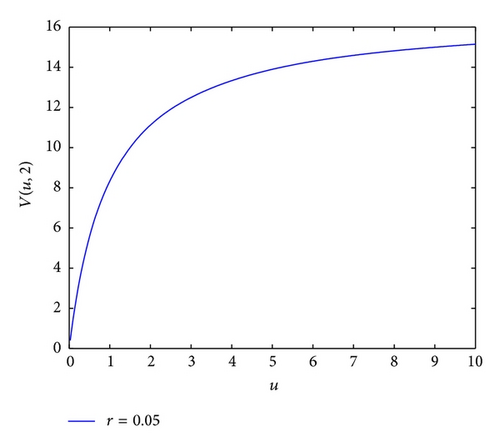

Example 1. Let c1 = 0.1, c2 = 0.2, μ = 5, α = β = π/4, λ = 3, b = 2, σ = 0.05, δ = 0.006, , , d = 1/4000, and r = 0.05, the result is shown in Figure 1.

From Figure 1, we see that V(u; 2) is an increasing function with respect to u.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant nos. 61370096 and 61173012 and the Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province under Grant no. 12JJA005.

Appendix

The sinc method is a highly efficient numerical method developed by Stenger, the pioneer of this field, people in his school, and others [18–22]. It is widely used in various fields of numerical analysis such as interpolation, quadrature, approximation of transforms, and solution of integral, ordinary differential, and partial differential equations.

Definition A.1 (see [19], P73, De. 1.5.2.)Let ϕ denote a smooth one-to-one transformation of an arc Γ with end-point t1 and t2 onto ℝ, such that ϕ(t1) = −∞ and ϕ(t2) = ∞. Let ψ = ϕ−1 denote the inverse map, so that

Given ϕ, ψ, and a positive number h, define the sinc points zk by

Observe that ρ(z) increases from 0 to ∞ as z traverses Γ from t1 to t2.

Corresponding to positive numbers , , and d, let denote the family of all functions f defined on Γ for which

Another important family of functions is , with , and 0 < d < π. It consists of all those functions f defined on Γ such that and where Lf is defined by Lf = (f(t1) + ρ(x)f(t2))/(1 + ρ(x)).

Let N and M denote two positive integers, such that , or where [·] denotes the greatest integer function. Moreover, we denote m = M + N + 1.

Definition A.2. Given three positive integers N, M, and m as above, let Dm and Vm denote linear operators acting on functions f defined on Γ given by

Theorem A.3 (see [19], P85, Th. 1.5.13.)Let ; then, as N → ∞,

Theorem A.4 (see [19], P87, Th. 1.5.14.)Let ; then,

Theorem A.5 (see [19], P93, Th. 1.5.19.)Let ; then, for all N > 1,

Theorem A.6 (see [19], P95-96, Th. 1.5.20.)Let ; suppose that A± can be diagonalized with A+ = XSX−1 and with A− = YSY−1 and that S is a diagonal matrix. If for some positive c′ independent of N, one has F′(s) ≤ c′ for all ℜs ≥ 0, then there exists a constant C independent of N such that

Theorem A.7 (see [18], P106, Th. 4.1.)Let ϕ be a conformal one-to-one transformation of an arc Γ. Then,